Introducing Volcanology

Companion titles

Introducing Geology – A Guide to the World of Rocks (Second Edition 2010)

Introducing Palaeontology – A Guide to Ancient Life (2010)

Introducing Meteorology (2012)

Introducing Geomorphology – A Guide to Landforms and Processes (2012)

Introducing Tectonics, Rock Structures and Mountain Belts (2012)

Introducing Oceanography (2012)

For further details of these and other Dunedin Earth and Environmental Sciences titles see:

www.dunedinacademicpress.co.uk

ISBN 978-1-906716-21-9

ISBN 978-1-906716-15-8

ISBN 978-1-780460-02-4

ISBN 978-19067163-25-7

ISBN 978-1-906716-26-4

ISBN 978-1-78046-001-7

Introducing Volcanology

A Guide to Hot Rocks

This book is dedicated to Jo and Izabel

(Izzy – the Great Cornsteiny)

Volcano……BOOM!!!

Published by

Dunedin Academic Press Ltd

www.dunedinacademicpress.co.uk

Head Office: Hudson House,

8 Albany Street, Edinburgh EH1 3QB

London Office: The Towers,

54 Vartry Road, London N15 6PU

Paperback book: 9781906716226

ePub: 9781903544419

ePub (Amazon/Kindle): 9781903544648

ePub (iPad, Fixed Layout): 9781903544655

© Dougal Jerram 2011

The right of Dougal Jerram to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission, except for fair dealing under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or in accordance with the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Society in respect of photocopying or reprographic reproduction. Full acknowledgment as to author, publisher and source must be given. Application for permission for any other use of copyright material should be made in writing to the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Makar Publishing Production, Edinburgh

Printed in Poland by Hussar Books

Contents

List of Illustrations and Tables

Illustration Credits and Acknowledgements

Preface

1 The world of volcanoes

2 The cooling Earth – how do rocks melt?

3 Volcanoes, plate tectonics and planets

4 Types and scales of eruption

5 Lava flows and bubbling cauldrons

6 Explosive pyroclastic eruptions and their deposits

7 Igneous intrusions – a window into volcano plumbing

8 Volcanoes, life and climate

9 Monitoring volcanoes

10 Volcanoes and Man

Glossary – Dr Volcano’s A–Z of volcanoes

List of Illustrations and Tables

1.1 Drawings of volcanoes by children

1.2 Example of a volcanic plume (eruption)

1.3 Sampling lava looking at ancient deposits

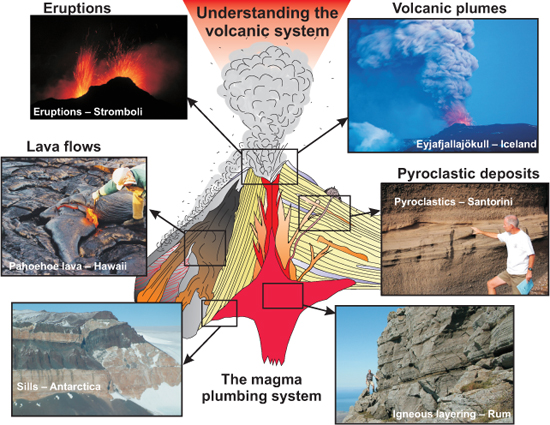

1.4 Understanding the volcanic system

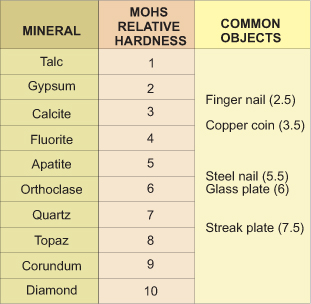

1.5 Mohs’ hardness scale

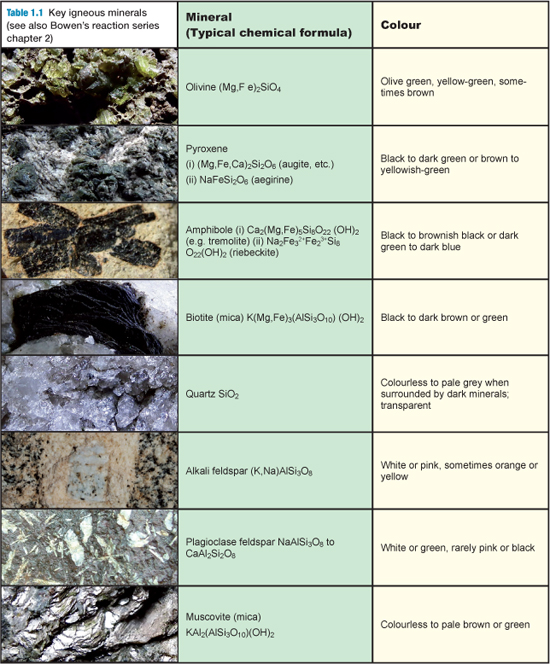

Table 1.1 Key minerals found in igneous rocks

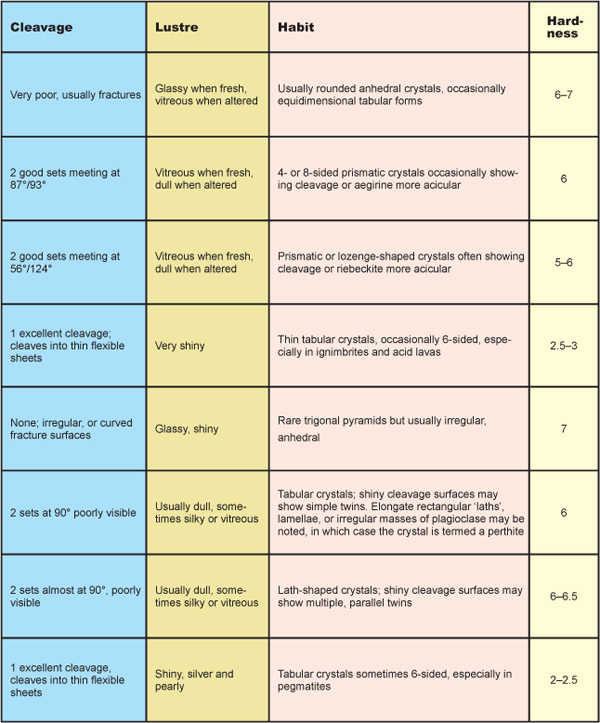

1.6 Igneous classification scheme

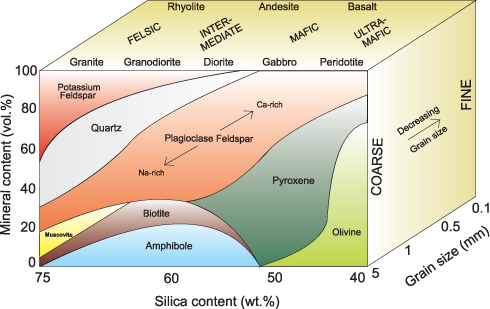

1.7 Summary of volcanic hazards

2.1 Cross section through the Earth

2.2 Dr Volcano’s guide to melting rocks

2.3 Bowen’s reaction series

2.4 Modern melt experiments

2.5 The Earth’s geotherms and melting

2.6 Zoning in crystals vs zoning in a tree

3.1 Plate tectonic maps highlighting volcanoes and earthquakes

3.2 Three-dimensional plate boundaries model

3.3 Map of Icelandic ridges and photo of ridge

3.4 Hawaiian island chain and hot spot

3.5 Olympus Mons, Mars

3.6 Volcanism on Jupiter’s Moon Io

4.1 Illustrations of different styles of volcano

4.2 The basic classification of different volcanoes

4.3 Key types of volcanic eruption

4.4 Height versus explosivity for key types of eruption

Table 4.1 Volcanic Explosivity Index, VEI

4.5 Volcanic explosivity index in graphical form

4.6 Eruption column of a volcano viewed from space

4.7 Timing of eruptions from the Cascades range, USA

4.8 Map of large igneous provinces (LIPs) of the world

5.1 Spectacular pictures of lava flows

5.2 Emplacement of lava flows by inflation

5.3 Examples of pāhoehoe and a’a lava surfaces

5.4 Lava flow features from Colima, Mexico

5.5 Columnar cooling joints, entablature and colonnade

5.6 Internal structures, crystals and vesicles

5.7 Amethyst geodes

5.8 Examples of lava tubes

5.9 Pillows and hyaloclastites

5.10 Lava lakes

5.11 Unusual types of flow

6.1 Examples of explosive eruptions

6.2 Size and types of volcanic clasts

6.3 Photos of different juvenile components, bombs, etc

6.4 Schematic summary of a pyroclastic flow

6.5 Topography of eruptive products

6.6 Pyroclastic classification schemes

6.7 Schematic through an ignimbrite deposit

6.8 Photo examples of ignimbrites

6.9 Example of welded ignimbrite

6.10 Eruptions through and beneath the sea

7.1 Schematic of a volcano plumbing system

7.2 Simple sketches of dykes and sills with examples

7.3 Intrusions in three dimensions from seismic images

7.4 Dyke swarms in Northern Ireland

7.5 Volcano plumbing on the Isle of Elba, Italy

7.6 The Scottish volcanic centres

7.7 Schematic reconstruction of the Rum volcano

7.8 Section through an ophiolite with examples

7.9 Kimberlite volcanoes

7.10 Three-dimensional plumbing beneath Hawaii

8.1 Large Igneous Province (LIP) map

8.2 Correlation between LIPs and mass extinction events

8.3 Gases from volcanic plumes

8.4 Modelling the 1783 Laki eruption plume

8.5 Photo of Pinatubo eruption column

8.6 Pinatubo and climate change

9.1. Deploying seismic stations on the side of a volcano

9.2 Seismic signals from Montserrat

9.3 Gas monitoring at Colima, Mexico

9.4 GPS movements on Iceland

9.5 Mapping volcanic deformation with satellites

9.6 Thermal imaging of volcanoes

9.7 Virtual volcano; the 3D reconstruction of a lava lake

10.1 Man living with volcanoes

10.2 Snow monkeys of Japan

10.3 The Toba eruption

10.4 Map of the Bay of Naples

10.5 Eruption of Vesuvius reconstructed

10.6 Body casts at Pompeii

10.7 Bones at Herculaneum

10.8 Mt St Helens before and after the eruption

10.9 The location of Eyjafjallajökull and Katla on Iceland

10.10 Eruptions from the Iceland volcanic crisis

10.11 Satellite images of the Iceland volcanic plume

10.12 Plumbing of the Iceland system

Illustration Credits and Acknowledgements

Unless otherwise indicated the photographs, tables and other figures used are those of the author.

The following illustrations are reproduced by permission, courtesy of:

Figures 2.1, 3.4, 4.2, 4.5, 5.3, 8.3, U. S. Geological Survey; Figures 1.2 and 6.1, Rick Hoblitt, U.S. Geological Survey; Figure 6.4, Peter W. Lipman, U.S. Geological Survey (image 113); Figure 8.5, Dave Harlow, U.S. Geological Survey; Figure 10.8, Lyn Topinka, U.S. Geological Survey. Figures 1.4, 4.1, 5.1 and 10.10, Jón Viðar Sigurðsson; Figure 2.4, Lori Dickson; Figure 2.6, a) Jon Davidson, b) Adrian Pingstone; Figures 3.5, 3.6, 4.6, 5.10, 6.1, 8.6, 9.4, 10.3, 10.9, 10.11, NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL); Figure 3.5, Malin Space Science Systems; Figure 4.3, Ivan d’Hostingue (a.k.a. Sémhur on Wikimedia Commons, © CC-BY-SA 3.0); Figures 5.9 and 6.10b-d Joseph Resing, Marine Geoscience Data System; Figure 5.11, Rob Evans; Figure 6.10a, Howell Williams, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Figure 7.4, Mark Cooper, Geological Survey of Northern Ireland, Tellus project, http://www.bgs.ac.uk/gsni/tellus/index.html, see Cooper et al., (2012). Palaeogene Alpine tectonics and Icelandic plume-related magmatism and deformation in Ireland. Journal of the Geological Society, London. Vol. 169; Figure 7.5, Sergio Rocchi; Figure 7.9a, I. Bothar, Wikimedia Commons © CC-BY-SA 3.0; Figure 8.1, Henrik Svensen; Figure 8.4 Vincent Coutillot (see also V. Courtillot, F. Fluteau et A.L. Chenet, Des éruptions volcaniques ravageuses, Dossier Pour la Science N°51, avril–juin 2006); Figure 9.2, Jurgen Neuberg, data courtesy Montserrat Volcano Observatory; Figure 9.3, Julie Roberge; Figure 9.6b & c, William Hutchison and Nick Varley, Centre of Exchange and Research in Volcanology, Universidad de Colima, – http://www.ucol.mx/ciiv; Figure 10.2, photo by wiki user Yosemite © CC-BY-SA 3.0; Figure 10.4 Martin C. Doege (based on NASA SRTM3 data); Figure 10.5 Media from the Discovery Channel’s Pompeii: The Last Day, courtesy of Crew Creative Ltd; Figure 10.8, Jim Nieland, U.S. Forest Service; Figure 10.9, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

The following illustrations have been adapted from published sources:

Figure 1.7: Myers, B. and Driedger, C. (2008) Geologic Hazards at Volcanoes, U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 64, USGS. Figure 3.1: Graham Park, (2010) Introducing Geology, Dunedin Academic Press. Figure 4.7: Myers, B. and Driedger, C. (2008) General Information Product 63, USGS. Figure 4.8: Image courtesy of Mike Coffin, from: Coffin, M.F., Duncan, R.A., Eldholm, O., Fitton, J.G., Frey, F.A., Larsen, H.C., Mahoney, J.J., Saunders, A.D., Schlich, R., and Wallace, P.J. (2006) Large igneous provinces and scientific ocean drilling: status quo and a look ahead, Oceanography 19(4), 150–160. Figure 6.2: Lockwood, J.P. and Hazlett, R.W. (2010) Volcanoes: Global Perspectives, Wiley-Blackwell. Figure 6.7: Sparks et al. (1973) Geology; 1(3), 115–118. Figures 7.2c, 7.3b: Image courtesy of Nick Schofield, from: Goulty, N. and Schofield, N., (2008) Implications of simple flexure theory for the formation of saucer-shaped sills. Journal of Structural Geology, 30, 812–817. Figure 7.6: Emeleus, C.H. & Bell, B.R. (2005) British Regional Geology: the Palaeogene Volcanic Districts of Scotland. British Geological Survey. Figure 7.7: Jerram, D. and Goodenough, K. (2008) Golden Rum, bicentenary field report, Geoscientist Volume 18, No. 3. http://www.geolsoc.org.uk/page3345.html. Figure 7.10: Ryan, M.P. (1988) The mechanics and three-dimensional internal structure of active magmatic systems: Kilauea volcano, Hawaii: Journal of Geophysical Research, 93, 4213–4248. Figure 8.2: White, R.V. and Saunders, A.D. (2005) Volcanism, impact and mass extinctions: incredible or credible coincidences. Lithos, 79, 299–316. Figures 9.4, 9.5: Images courtesy of Freysteinn Sigmundsson from Sigmundsson et al. (2010) Intrusion triggering of the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull explosive eruption, Nature, 468, 426–431. Figure 9.7: Jerram, D. and Smith, S. (2010) Earth’s Hottest Place, Geoscientist, Volume 20, No. 2, 12–13 http://www.geolsoc.org.uk/gsl/geoscientist/features/page7072.html. Figure 10.2: Images courtesy of Freysteinn Sigmundsson from Sigmundsson et al. (2010) Intrusion triggering of the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull explosive eruption, Nature, 468, 426–431.

In addition, Catherine Nelson and Richard Brown are thanked for their valuable input, and Brian Upton and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive and helpful comments.

Preface

Volcanoes have the power to rock our world, from the spectacular and the beautiful to the violent and the deadly. Ever since our planet was formed, volcanoes have played a constant and vital role in its evolution and in the evolution of life on the planet. In this guide to ‘hot rocks’ we follow a journey to unravel the mysteries behind volcanoes, what they are, why and where they erupt and how they have affected the Earth and Man through time. Understanding Volcanology is a detailed but accessible introduction to volcanoes and their plumbing systems. Aimed at those with an inquisitive interest in volcanoes as well as the more advanced reader, the ten chapters document different aspects of volcanology. All are illustrated with a wide array of photographs and diagrams to accompany the text, and an A–Z of volcanology is included as a glossary.

As an Earth Scientist with a particular soft spot for hot rocks, I have travelled the world far and wide looking at recent and ancient volcanic rocks. I have shared my experiences in lecture theatres of universities, with interested school parties, and through science outreach activities in the media. Appearing as ‘Dr Volcano’ on BBC television I have explained the recent Iceland volcanic crisis, and described in detail how to look at igneous and volcanic rocks while doing fieldwork with my first joint book, The Field Description of Igneous Rocks (Jerram & Petford, Wiley 2011). I have touched on elements of volcanology and geology through a variety of TV, Radio and press activities (BBC, Discovery, National Geographic, History Channel, Channel 4, BBC Worldwide, etc.) and have set my virtual home up at dougalearth.com. The world is a wonderful place; I want to bring an understanding of its geology to the widest possible audience. This book is my first solo Earth Sciences text and it is very appropriate that it is about volcanoes, the driving force that makes the Earth work. I hope you find Understanding Volcanology a very informative text and an even more valuable source of images and graphics that help your understanding of volcanoes, and inspire you to delve more deeply into Earth Science and the wonderful knowledge it can bring.

Dr Dougal A. Jerram, AKA ‘Dr Volcano’

Figure 1.1 a) Drawings of volcanoes by children: Fleur Meston (age 11), winner of Dr Volcano’s schools drawing competition from over 300 entries; runners-up.

Figure 1.1 b) Drawings of volcanoes by children: Charlotte Miller (age 11).

Figure 1.1 c) Drawings of volcanoes by children: James Macaulay (age 11).

Figure 1.1 d) Drawings of volcanoes by children: Emma Smailes (age 10).

Figure 1.1 e) Drawings of volcanoes by children: Charles Lang (age 7).

1The world of volcanoes

Ask any child to draw a volcano and they will eagerly beaver away to produce an array of imaginative depictions of volcanic eruptions, volcanic islands and towering conical mountains. Figure 1.1 highlights some of such examples of volcanic handiwork from children – a truly fascinating insight into how, even at an early age, volcanoes form a part of our psyche. Our fascination with volcanoes is like some primordial link between ourselves and our planet. But what of the world of volcanoes? Many of us will not have seen an active volcano in the flesh and will never get to see one erupt. Until the recent Icelandic volcanic crisis, which closed down airspace and disrupted everyday lives in Europe and North America, our fascination with volcanoes was still that of a child: for a mythical land of volcanoes, dinosaurs and ancient Earth, somehow linked with Man.

Today there are more than 500 plus active volcanoes on this planet; about twenty will be erupting whilst you read this passage, and others that we can observe elsewhere in the Solar System. The Earth’s volcanoes are testament to the planet’s cooling and the convection of heat manifest on the Earth’s surface in plate tectonics. Volcanoes allow the planet to breathe; the gases they emit have helped to develop the Earth’s atmosphere and contribute a key part of the present atmospheric cycle. To understand the world of volcanoes we need to look at the Earth system as a whole, from its very centre to the volcanic plumes in the air (Figure 1.2). We need to understand the plumbing systems that feed the volcanoes; the varied types of eruption that are seen on Earth; and to look to those beyond our planet. As volcanologists, our goal is to be able to put together ALL the pieces, from what makes rocks melt, to the different compositions of magma that result in the wide variety of eruption types and settings.

Studying volcanoes

The way in which volcanoes are studied can be placed into two main categories, which have some overlap in time and space. First, there are modern volcanoes, those that are active and erupting on the Earth’s surface today. These can be monitored and measured (Figure 1.3a); their changes through time are noted, as is their location on the planet, particularly where they may affect Man. Secondly, the ancient rock record is studied to see how volcanoes erupted and occurred in the past (Figure 1.3b) – how they have helped build the planet and change the course of the Earth’s history. Volcanoes can be linked to the emergence of life and also to mass extinctions that have occurred at key points in our planet’s history. They are important sources of materials and resources, from diamonds to the ‘burnt umber’ watercolours children use to paint volcanoes. The study of modern and ancient volcanoes overlaps as, with the investigation of the previous products of active volcanoes, deposits can range in age from very recent eruptions to those that are tens, thousands or millions of years old. This information from the volcanoes’ recent and, sometimes, distant history helps us unravel what has happened in the past; to look for patterns of volcanic activity through time; and to use this as a form of remote monitoring to help predict what any particular volcano may do in the future.

Figure 1.2 Example of a volcanic plume (eruption). 22 July 1980 eruption of Mt St. Helens, second eruptive pulse as seen from the south (U.S. Geological Survey).

Each major volcanic eruption that is witnessed has its own tale to tell about the way in which volcanoes behave. Eruptions have an increasing effect on Man as mankind’s population grows and the planet is used in more sophisticated ways, for example the impact on air travel of the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland in 2010. Further, as time goes by, our chances of seeing the larger, rarer, eruptions slowly increase as the odds of them erupting reduce.

Figure 1.3 a) Sampling lava and looking at ancient deposits. Sampling lava on Hawaii.

Figure 1.3 b) Sampling lava and looking at ancient deposits. surveying a volcanic fissure in Ethiopia.

Figure 1.3 c) Sampling lava and looking at ancient deposits. looking at pyroclastic deposits on Santorini.

How do I start?

You do not have to travel too far to be able to start on your quest to become a volcanologist. Some basic background knowledge, some simple but effective field gear and a keen eye for rocks should set you on the right path to delve into the world of volcanoes.

A useful approach is to take a top-down look at the volcano or volcanic/igneous rocks that you are interested in. You can consider the basic components that make up the volcanic system, from its underground plumbing to the products that it erupts at the surface (Figure 1.4). Within the plumbing systems of volcanoes are magma chambers, which act as storage vats for the molten rocks on the way to the surface, and dykes and sills, which link between chambers and also from its depths to the visible volcano at the surface. Clearly in modern systems these are hidden beneath the volcano, but their movements may be monitored remotely (Chapter 9). In ancient examples, where erosion has exposed the inner workings of the volcano, the ‘fossilised’ magma plumbing system can be explored to help us understand how it works (Chapter 7). At the surface there may be lava flows and explosive eruptions that lead to a wide variety of volcano types and sizes (Chapter 4). Different types of lava flows, from recent to ancient (Chapter 5) may be looked at, and modern explosive eruptions can be compared with similar eruptions preserved in the ancient rock record (Chapter 6). In order to better understand the products from volcanoes and their plumbing systems, a much closer look is needed at the fine scale detail shown by their associated minerals and rocks.

Figure 1.4 Understanding the volcanic system. In order to understand the volcanic system we have to look at every aspect from the volcano’s plumbing system to the wide range of products it erupts at the surface. (Iceland photo by Jón Viðar Sigurðsson)

Igneous minerals

On the detailed scale, the rocks themselves must be understood to reveal what they mean in terms of the different volcanoes. A good start here is to understand some of the basic mineralogy of the rocks that are formed from volcanoes and their associated ‘plumbing’ systems. Igneous rocks are made up of various elements which, depending on the composition, lead to different crystals forming as they cool, resulting, in turn, in different types of igneous rocks. A lot can be deduced about the origin of the magma associated with a particular volcano, depending on the composition of the crystals and minerals that form as it cools. This subject will be covered in more detail in the next chapter. Close investigation into the literature of mineralogy reveals a bewildering array of different types of minerals that exist. Fortunately, with igneous rocks you will initially only need to master a handful of key rock-forming minerals in order to start to understand your volcano. Minerals are characterised in the following ways (see Table 1.1):

Colour: the colour of the mineral under normal light; this can be very typical for some minerals, and quite variable in others.

Streak: a property of colour when a mineral is scratched along a porcelain plate (really only of use in a few examples – mainly iron oxides).

Lustre: the way in which minerals reflect light; for example, are they glassy, metallic, or dull.

Hardness: this is a scale from 1 to 10 where 10 is diamond, the hardest mineral known to us on the planet (Figure 1.5).

Cleavage and Fracture: Cleavage is where a mineral breaks along planes of weakness in its structure. Minerals can have one, two or three cleavages. Fracture is the way in which a mineral breaks apart in a non-linear fashion and can be characteristic of some key minerals.

Shape (also known as habit): minerals can be described as being euhedral (good crystal form), subhedral (moderate crystal form) and anhedral (showing no crystal form). The crystals themselves may be bladed, tabular, fibrous, blocky, rounded, or prismatic.

Other properties: including taste (for example, halite – rock salt), magnetism (for example, magnetite).

In most examples you will not be able to test or see all of these properties, but they are useful to know in case you have large crystals in your volcanic rocks.

Additionally, minerals can be subdivided into seven crystal systems, based on their symmetry and physical properties: cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, trigonal, and hexagonal. Again, a detailed understanding of these systems is not important initially, but when faced with a table of mineral types you will inevitably come across these names. As you get to know your minerals better, you will start to see how things like the crystal system will help dictate the form of the resultant minerals, and why they have certain key properties. Some of the key minerals and their characteristics are given in Table 1.1. As the discussion develops in Chapter 2 concerning how rocks melt, it will become clear how these minerals fit into our understanding of volcanoes, and the way in which they can be used to help constrain volcanic process.

Figure 1.5 Mohs hardness scale. Ranges from 1 (softest) to 10 (hardest) with key minerals for each hardness range and the hardness of some common objects indicated.

Basic classification of igneous rocks

We do need to know the basic classification system of igneous rocks – how they are grouped in order to put each type of volcanic rock into the broader context. Igneous rocks are classified according to the different relative amounts of the key minerals outlined in Table 1.1. Each mineral is made up of its constituent elements, and as the quantity of each mineral type varies, different rocks are composed. In general, igneous rocks range in composition from being relatively rich in iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg), known as mafic rocks, to rocks that are rich in silica (SiO2, silicon oxide) and aluminium (Al), known as acidic rocks.

Rocks can be classified by their grain size as well as by their chemistry. This is used to help distinguish plutonic rocks, those which have cooled slowly at depth, from shallow intrusions and volcanic rocks, which erupt at the Earth’s surface and cool very quickly. With plutonic rocks, the slow crystallisation leads to large crystals, whereas rapid cooling results in very small-grained crystals or even glass. A simple classification scheme for igneous rocks is presented in Figure 1.6, which combines the relative compositions of the rock types with the grain size to give a number of rock classification names. Basic rocks rich in iron and magnesium range from coarse-grained gabbros through medium-grained dolerite to fine-grained basalt. You may come across people calling mafic rocks ‘basaltic’ in composition, which can sometimes be used in a non-grain size sense. Acidic rocks range from coarse-grained granites, through micro-granites to fine-grained rhyolite. Intermediate between these are andesites and dacites (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 Igneous classification scheme. General classification scheme for igneous rocks based on grain size, silica content and relative abundance of igneous rock-forming minerals.

Volcanoes as hazards

Active volcanoes present a number of hazards to Man. Due to the very fertile land around volcanoes, Man has long colonised many of the world’s volcanically active areas. Indeed, volcanic island chains and isolated island hot spots owe their very existence to the volcanoes that build them. There are the direct hazards associated with the eruption of a volcano. These, as shall be demonstrated, are particularly important for some of the more explosive volcanoes (summary in Figure 1.7). Pyroclastic flows, bombs, ash and lava direct from a volcanic eruption can have devastating effects on the immediate and closely surrounding areas. Associated with any direct explosive activity may be the collapse of part of the side of the volcano or the collapse of domes of new magma that collect at the top of the volcano. Further away, an eruption can destabilise the landscape, leading to mudslides (lahars) which can often be more deadly than the original eruption. For example, a mud flow in Columbia, after the 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz stratovolcano in Tolima, is thought to have killed some 23,000 people. Even more remote are the effects on the climate from large eruptions, which can change the planet’s climate for a few years, as has been experienced during Man’s time on the planet, or, in extreme cases, change the whole course of evolution.

Figure 1.7 Summary of volcanic hazards. (Myers and Driedger, 2008)

In order to fully understand our volcanic planet it is necessary to understand why rocks melt; to understand how and where volcanoes occur on our planet; and to recognise the types of volcano and why they occur. The differing sizes of volcanoes and how they are classified should be learnt. The past is the key to the present, and so a good understanding of key volcanic events through time also helps introduce the world of hot rocks.

2The cooling Earth – how do rocks melt?

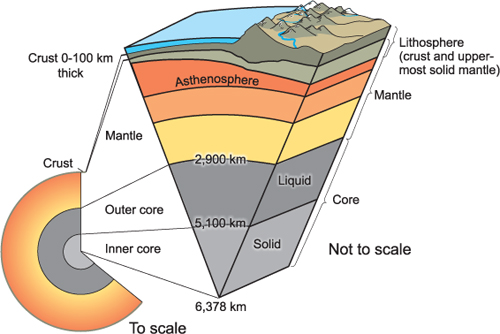

For the Earth to have volcanoes there must be a source of heat within the planet, there must be a mechanism for melting rock and there must be a way for that molten rock to get to the surface. To understand why rocks melt, the starting point is the current structure of the Earth. Our planet is made up of layers that are broadly defined by their composition and behaviour. Figure 2.1 provides a schematic cross section through the Earth, from its centre (some 6378 km from the surface) through to the thin veneer of crust and atmosphere.

The Earth’s basic structure can be broken down into the following layers: the inner core with a radius of some 1200 km, which is solid and almost entirely composed of iron. The outer core surrounding this is about 2300 km thick, is liquid, and is composed mainly of a nickel-iron alloy. The Earth’s magnetic field is believed to be controlled by this liquid outer core. The next layer from the centre is the mantle, which is around 2900 km thick, is so viscous as to be almost solid, and is composed mainly of silicates rich in iron and magnesium. The slow circulation of heat through the mantle over time is thought to be one of the driving forces for plate tectonic processes, and is important in our understanding of volcanoes. The outermost layer of the Earth is the crust, which can be divided into continental and oceanic crust. The crust has a variable thickness, with continental crust being some 35–70 km thick and the oceanic crust some 8–10 km thick. The continental crust is composed mainly of silicates rich in aluminium, whilst the oceanic crust contains more iron and magnesium. The crust and the uppermost part of the mantle, which behave as the rigid shell of the planet, is known as the lithosphere (see Chapter 3).

Figure 2.1 Cross section through the Earth. The different parts of the Earth’s internal structure. (U.S. Geological Survey)