Six Records of a Floating Life

Translated with an Introduction and Notes by

Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui

Penguin Books

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

This translation first published 1983

27

All rights reserved

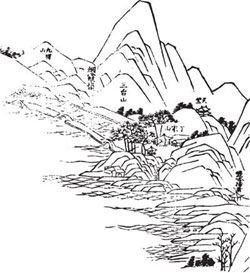

Maps on pages 166–7 by Reginald Piggott

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

9780141920344

Contents

Introduction

Chronology

Weights and Measures

Six Records of a Floating Life

PART I: The Joys of the Wedding Chamber

PART II: The Pleasures of Leisure

PART III: The Sorrows of Misfortune

PART IV: The Delights of Roaming Afar

Appendices

1 A History of Life at Chungshan

2 The Way of Living

Notes

Maps

Now the heavens and earth are the hostels of creation; and time has seen a full hundred generations. Ah, this floating life, like a dream… True happiness is so rare!

LI PO, ‘On a Banquet with my Cousins

on a Spring Night in the Peach Garden’

Introduction

Shen Fu was born in Soochow in the latter part of the eighteenth century, at the height of the Ch’ing Dynasty. He was a government clerk, a painter, occasional trader, and a tragic lover, and in his mid forties he set out his life in six moving ‘records’ that have delighted the Chinese ever since they came to light in the nineteenth century.

While it is much more, the Six Records is known among the Chinese as a love story. As such, from a Western point of view, it is unique. For though it is indeed a true love story of Shen Fu and his wife Yün, it is a love story set in a traditional Chinese society – and thus their love coexists and intermingles with Shen Fu’s affairs with courtesans, and with his wife’s attempts to find him a concubine. And yet, for all that, it is none the less love.

The role of the courtesan as described in the Six Records is an example of what makes the book a valuable social document. It is difficult for Westerners to understand just what a courtesan in China was, because the only equivalent we have for the role is a prostitute. But a courtesan properly called was respectable and respected, and her sexual favours were by no means necessarily for sale. As van Gulik has described in his classic Sexual Life in Ancient China (Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, N.J., 1974), a courtesan could often be more independent and powerful than the men she ostensibly served. It is this kind of small but significant alteration to our perceptions and presumptions which the Six Records can effect that makes it so important a book for Westerners.

Chinese readers find something else in it. It must be recalled how common arranged marriages were among the Chinese until quite recently. Even now, a great deal of parental influence, or economic or social coercion, is still present as an influence in the choice of marriage partners in many Chinese societies.

And so a book arising out of the Imperial literary tradition that extolled enduring, romantic love easily became, and has remained, a favourite among Chinese readers: it has recently been reissued in China by the People’s Literature Publishing Society, and is certainly the first primarily romantic book to come out in China for decades.

Shen Fu has described his life with his wife in what is probably the most frank and moving story to come to us from the literature of his time. He has given us a remarkable picture of Yün, his child love and his wife. Her life was hard but she played on all its graces, and Shen Fu’s portrait of her manages to infuse the greatest tenderness into what is one of the most realistic accounts of the life of a woman ever given in traditional Chinese literature.

The book’s remarkable frankness is broader than that, however. Official literature of the Imperial period, of course, tells us little of the daily life of the more ordinary Chinese people. Novels, plays, and tales of mystery do tell us a bit, but are often so taken up with details of their plots that there is little space left over to tell how people living in China then actually spent their time. The Six Records does tell us in great detail, while managing to avoid many of what must seem to Western readers to be the convolutions that plague so much Chinese popular literature of the time. Fortunately for us, Shen Fu accomplished a rare feat in traditional China: he became literate without becoming a literatus.

Shen Fu was, by his standards and by our own, a conspicuous failure in many ways. The highest he rose officially was to the position of private secretary to a powerful friend, a role that fell to many luckless literati of the Ch’ing. He was not much of a painter, he was a poor businessman frequently in debt, and by the end of his book he seems to have become entirely estranged from his family.

Yet while he was so often a victim, he was still determinedly upright when the chance to be so came his way. He resigned one official post in disgust at his colleagues’ misdeeds, and he is gentleman enough not to tell us what they did that so upset him. He restored a peasant girl to her family when a man of influence was trying to force her to become a concubine. He was a trusting friend, often to his cost.

If Shen Fu was a failure in so many ways, much of his failure was related to the class from which he came – the yamen private secretary. The secretaries in a yamen – a government office – were failures almost by definition.

The origin of the profession of yamen secretary lay in two uniquely Chinese administrative practices. The first was a rule against assigning magistrates to their home districts. Throughout the post-feudal Chinese dynasties this was a standard means of attempting to ensure that officials administered their districts honestly, unswayed by local loyalties or favourites.

The second practice arose from the Chinese determination that government officials should be scholars first and bureaucrats second. One of the largest empires in the history of the world was administered by a small group of men who, prior to their first assignment, had not had the slightest training in administration, and who knew more about the poetry of a thousand years before than they did about tax law.

The typical Chinese magistrate, therefore, found himself in a district of which he had little personal knowledge – indeed, he might be woefully ignorant even of the local dialect of the language – and with only the slightest acquaintance with the complex laws and customs by which he was supposed to carry out his manifold responsibilities. He needed help, and he found it in the private secretary.

Literate and technically skilled, the private secretary was the magistrate’s link between the scholarly ethics and the practical realities of Imperial Chinese government. T’ung-tsu Ch’ü (Local Government in China Under the Ch’ing, Harvard University Press, 1962) divides the secretaries into seven categories of specialists: law, tax administration, tax collection, registration of documents, correspondence, preparation of documents, and book-keeping. It is nowhere stated clearly in the Six Records, but Shen Fu seems to have specialized in law, the most prestigious of the seven.

The secretaries prepared almost every document a magistrate saw. They recommended decisions for him, handled virtually all his official correspondence, helped organize court sessions, and drafted replies on his behalf to official queries about his actions, actions which probably had been recommended by themselves in the first place. The quality of his secretaries could make or break a magistrate’s career; they were very powerful.

They were also very unofficial. Except for one brief and unsuccessful experiment, the Ch’ing Dynasty never officially recognized their existence. They were the employees of the magistrate – not of the government – recruited by him and paid out of his personal funds. They were well paid – Ch’ü estimates they were the only members of a yamen staff able to support themselves on their salaries – and well respected. Whenever Shen Fu records going to work for a magistrate, he describes himself as being ‘invited’ to take the position; this is not an affectation. Once employed, the secretaries were far more than servants; resignation in protest was far from uncommon and, as noted above, Shen Fu himself seems to have done it at least once.

Who were the private secretaries, and where did they come from? Since they were well educated – they had to be in order to do their jobs – most had, on one or more occasions, taken the examinations which were the natural culmination of the education system of the day. If they had passed those examinations – and some of course did – they would have become officials themselves, rather than secretaries. We are talking, therefore, about a group of men who had either denied, or had been denied, entrance to the scholar-official class; men who had studied for the highest posts and failed to attain even the lowest.

It must have been a painful situation. Raised in the traditions of China’s greatest poets and administrators, they were forced to live the only life their world offered them – itinerant and temporary employees, their only domain the shadowy world of yamen clerks, their only power that derived from their patron, towards whom it would have been only natural to feel a certain amount of jealousy.

All this must be kept in mind in considering what sort of man Shen Fu was, for it must be admitted that on the surface there are a fair number of unpleasant things about him. Perhaps the most difficult to understand is his repeated failure to provide for his family, apparently because it might not fit in with his image of himself. When his wife was ill and needed medicine, for example, he opened a shop to sell paintings – which he admits brought in only enough money to buy part of the medicine she needed – rather (we must unkindly note) than taking on a lower-status job that might have given him a more than occasional income.

Such facts are quite unquestionable; Shen Fu himself sets them out, though not as harshly as we have just done. So how much of a scoundrel was he? We leave that for the ultimate judgement of the reader, but we do think there are several points that ought to be remembered in making that judgement.

True, Shen Fu was a terrible romantic, a dreamer, often a victim of self-deception. But it should be noted that the education he received was intended exclusively to fit him for a part in life as a scholar-administrator; and beyond that education, no one of his class had much training at all. True, Shen Fu seems to us to cling to that education long after it has become irrelevant to his life; but perhaps he simply believed its promises, or was more enraptured by its graces, than others would have been. On a more practical level, it is worth asking what other profession he would have been suited for, had he decided to try to find something else to do; or, for that matter, what other profession his all-powerful parents would have allowed him to take up.

While granting all his personal faults, it seems to us that Shen Fu’s inability to assume responsibility was not really due to them. He was dealing with a difficult life with the only set of rules he understood; his tragedy was that they were not enough to see him through. It was this same tragedy that, a few decades after his book was written, began to overtake all his countrymen.

The original text of the book as we have it today is incomplete. The last two of the Six Records were lost before a manuscript of the book was discovered and published for the first time in the 1870s. During the 1930s the World Book Company published in Shanghai what it claimed was a complete text of the book discovered by one Wang Ch’ün-ch’ing in Soochow; in this form the book has recently gone through several impressions in Taiwan. The last two Records which it presents are known to be false, however, having been copied from works by other authors; details of these forgeries appear in two brief appendices to this translation. Apart from these pieces of information, we can add only the testimony of Shen Fu himself that he was working on the book in 1809.

The quality of the book presents some challenges. By his own admission, Shen Fu was not always the most explicit of writers. There are references in the book that are not clear, some that make little sense. Sometimes his facts are not consistent. There are also great differences between our modern ideas and Shen Fu’s of just what a book ought to be. The Six Records is not the chronologically constructed tale that we are now used to reading. Instead, Shen Fu takes particular topics and follows them each through his life, one at a time; the book is thus intended to be six different layers that add up to a ‘floating life’, each layer having little regard for its relationship to any other. Where we expect transitions, Shen Fu gives us few, and where we expect logical explanations he often gives us none. Sentences frequently stand almost by themselves. The book is meant to be mused over and, by our standards, read very slowly. There is much that is left unsaid. What is said, however, is rich in the life of the times. The troubled black sheep of a declining family, Shen Fu has left us a lively portrait of his era that in places strikes chords which are remarkably resonant with those of our own times.

It would be unusual if such a work had not come to the attention of translators before. Lin Yutang first translated the book in 1935, when it was serialized in the T’ien Hsia Monthly and in Hsi Feng. His translation of the entire book has appeared in several editions.

With the greatest respect for our predecessor, however, we felt that there was room for a full translation of the Six Records into modern English which would – by the use of extensive but, we hope, not intrusive notes and maps – present to the modern English reader a more complete exposition of the tale Shen Fu told. He wrote for an audience of his own time and place, and neither of those will ever live again. We hope that our contribution to this work may help it to live in the minds of today’s Western readers, as its author intended it should live in the minds of his contemporaries.

We have tried to provide a complete translation that is, in the words of Anthony C. Yu, ‘the most intelligible fidelity to the original’. Corrections to our work are inevitable, and we welcome them with the respect which is due to the original.

Chronology

When Shen Fu wrote the Six Records he made little attempt to organize the story of his life chronologically. For readers who may find it helpful, the following is taken from information provided by the book itself.

1763 Shen Fu was born, ten months after his wife-to-be.

1775 He met Yün for the first time, and his mother arranged their marriage; they were thirteen years old. The affair of the rice porridge occurred in this year.

1778 He began his travels around Hangchou while studying there. He took some examinations during this time.

1780 Shen Fu and Yün were married at the age of seventeen.

1781 His father fell ill, and Shen Fu was introduced to the profession of yamen private secretary. In the winter of this year he met his friend, the short-lived Hung-kan.

1783 He accepted a position at Weiyang (Yangchou), apparently his first independent posting.

1786 Yün gave birth to their daughter, Ching-chün.

1788 Shen Fu left official life in disgust after an unspecified incident at Chihsi. He tried his hand at trade during this year, but failed. His son Feng-sen was born.

1790 While Shen Fu worked with his father at Hungchiang, Yün upset the family by mishandling arrangements to obtain a concubine for her father-in-law.

1792 This year they were expelled from the family after a misunderstanding which involved Yün with a loan that had not been repaid by Shen Fu’s younger brother. They moved to the Villa of Serenity, where they lived for a year and a half. It was during this period that Shen Fu left on his profligate business trip to Canton.

1794 In the seventh month of this year Shen Fu returned from Canton. Shortly after his return, the matter of the loan was cleared up and they were allowed to return home.

1795 They met Han-yüan, the sing-song girl.

1800 Shen Fu paid his visit to the abandoned Wuyin Temple. Later in the year he and Yün were again expelled from the family, after he once more got involved in a quarrel about a loan, and after the family had become upset over Yün’s continuing friendship with Han-yüan. At the end of the year they moved to stay with friends, the Huas at Hsishan, and Yün saw their children, then aged twelve and fourteen, for the last time.

1801 A year of borrowing from Shen Fu’s brother-in-law and a friend. For most of this year and the next Shen Fu worked at the Hanchiang (Yangchou) Salt Bureau, while Yün remained at Hsishan.

1802 Yün’s health improved and she moved to join her husband at Yangchou. Shortly after that, he lost his job.

1803 Yün sickened again and died at Yangchou in the spring at the age of forty.

1804 Shen Fu’s father died. Late in the year Shen Fu visited the Yungtai Sands with his share-cropping friend Hsia Yi-shan.

1805 In the first month of this year he visited the Sea of Fragrant Flowers on Pu Mountain with Hsia Yi-shan. In September he became a retainer of his childhood friend Shih Cho-tang and began a journey with him to take up office in Szechuan.

1806 The party wintered at Chingchon in Hupei Province, then went on to Shantung in the tenth month. Shen Fu heard by letter that his son Feng-sen had died.

1807 Shen Fu moved to Peking in the autumn, when his patron Shih Cho-tang was assigned to the Hanlin Academy. While the text of the Six Records does not contain the information, it is known that Shen Fu in this year was appointed secretary to a diplomatic mission sent from the court in Peking to give Chinese recognition to a new king of the Ryukyu Islands.

1809 During the year Shen Fu was writing the Six Records, at the age of forty-six. Nothing is known of his life after this.

Weights and Measures

It was only after their revolutions that the Chinese truly began to unify their weights and measures. Standardization had begun in the mid nineteenth century with so-called ‘treaty port’ measures, but these were adopted largely for purposes of foreign trade and had little relevance to the rest of the country, where a complex and often contradictory system of local customs and usages continued to apply. Shen Fu was writing some decades before even the treaty port measures were introduced, moreover, so we would be misleading the reader if we offered the following as anything more than an approximate guide.

The catty A catty is customarily a measure of weight, ‘standardized’ in the nineteenth century at 1⅓ lbs. Shen Fu uses it as a capacity measure for wine, however, and as such it is usually taken to be equal to a pint.

The chang One chang is equal to 10 Chinese feet. In treaties of the nineteenth century the Chinese foot was defined as 14 English inches, which would make a chang equal to 11 feet 8 inches.

The jen An archaic measure equal to 7 Chinese feet, and thus to 8 English feet by treaty port definition.

The li The length of the li, or Chinese mile, has varied greatly with time, place, and circumstance. It is customarily taken to be about ⅓ of an English mile. Frequently, however, the li was less a measure of distance than it was a measure of effort required to cover a given distance; an uphill road would measure more li on the ascent than it would on the descent.

The mou The Chinese acre, which is usually converted at the rate set by nineteenth-century treaty in Shanghai as being equal to 1/6 of an English acre. By local practice, however, it could vary anywhere from 1/15 to ⅓ of an English acre. There are some indications that this variation may be accounted for by varying productivity of the land at the time the local standard was set. The real definition of a mou would thus be the amount of land required to produce a given yield, and a mou of high-quality land would be smaller than a mou of low-quality land. Local variations make this very difficult to establish with certainty, however.

The stone The picul, which could be either a capacity or a weight measure. Given the Chinese preference for weight measures it seems to us that this is what is intended here, and as such it was standardized at 133 lbs. Its real meaning varied greatly from place to place, however.

Translator’s Note

All romanization of Chinese names follows the Wade-Giles system; however, out of consideration for the general reader we have omitted aspiration marks in the body of the text, while retaining them in the notes. We have given Chinese place-names in English only where we believed they would make some sense in translation.