Table of Contents

Related Titles

Title Page

Copyright

To Annette and Alexander

Preface to the Second Edition

Preface to the First Edition

Abbreviations

1: Introduction

1.1 Why Organofluorine Chemistry?

1.2 History

1.3 The Basic Materials

1.4 The Unique Properties of Organofluorine Compounds

References

Part I Synthesis of Complex Organofluorine Compounds

2: Introduction of Fluorine

2.1 Perfluorination and Selective Direct Fluorination

2.2 Electrochemical Fluorination (ECF)

2.3 Nucleophilic Fluorination

2.4 Synthesis and Reactivity of Fluoroaromatic Compounds

2.5 Transformations of Functional Groups

2.6 “Electrophilic” Fluorination

References

3: Perfluoroalkylation

3.1 Radical Perfluoroalkylation

3.2 Nucleophilic Perfluoroalkylation

3.3 “Electrophilic” Perfluoroalkylation

3.4 Difluorocarbene and Fluorinated Cyclopropanes

References

4: Selected Fluorinated Structures and Reaction Types

4.1 Difluoromethylation and Halodifluoromethylation

4.2 The Perfluoroalkoxy Group

4.3 The Perfluoroalkylthio Group and Sulfur-Based Super-Electron-Withdrawing Groups

4.4 The Pentafluorosulfanyl Group and Related Structures

References

5: The Chemistry of Highly Fluorinated Olefins

5.1 Fluorinated Polymethines

5.2 Fluorinated Enol Ethers as Synthetic Building Blocks

References

Part II Fluorous Chemistry

6: Fluorous Chemistry

6.1 Fluorous Biphase Catalysis

References

7: Fluorous Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry

7.1 Fluorous Synthesis

7.2 Separation on Fluorous Stationary Phases

7.3 Fluorous Concepts in Combinatorial Chemistry

References

Part III Applications of Organofluorine Compounds

8: Halofluorocarbons, Hydrofluorocarbons, and Related Compounds

8.1 Polymers and Lubricants

8.2 Applications in the Electronics Industry

8.3 Fluorinated Dyes

8.4 Liquid Crystals for Active Matrix Liquid Crystal Displays

8.5 Fluorine in Organic Electronics

References

9: Pharmaceuticals and Other Biomedical Applications

9.1 Why Fluorinated Pharmaceuticals?

9.2 Lipophilicity and Substituent Effects

9.3 Hydrogen Bonding and Electrostatic Interactions

9.4 Stereoelectronic Effects and Conformation

9.5 Metabolic Stabilization and Modulation of Reaction Centers

9.6 Bioisosteric Mimicking

9.7 Mechanism-Based “Suicide” Inhibition

9.8 Fluorinated Radiopharmaceuticals

9.9 Inhalation Anesthetics

9.10 Blood Substitutes and Respiratory Fluids

9.11 Contrast Media and Medical Diagnostics

9.12 Agricultural Chemistry

References

Appendix A: Typical Synthetic Procedures

A.1 Selective Direct Fluorination

A.2 Hydrofluorination and Halofluorination

A.3 Electrophilic Fluorination with F-TEDA–BF4 (Selectfluor)

A.4 Fluorinations with DAST and BAST (Deoxofluor)

A.5 Fluorination of a Carboxylic Acid with Sulfur Tetrafluoride

A.6 Generation of a Trifluoromethoxy Group by Oxidative Fluorodesulfuration of a Xanthogenate

A.7 Oxidative Alkoxydifluorodesulfuration of Dithianylium Salts

A.8 Electrophilic Trifluoromethylation with Umemoto's Reagents

A.9 Nucleophilic Trifluoromethylation with Me3SiCF3

A.10 Transition Metal-Mediated Aromatic Perfluoroalkylation

A.11 Copper-Mediated Introduction of the Trifluoromethylthio Group

A.12 Substitution Reactions on Fluoroolefins and Fluoroarenes

A.13 Reactions with Difluoroenolates

References

Appendix B: Index of Synthetic Conversions

Index

Related Titles

Wirth, T. (ed.)

Organoselenium Chemistry

Synthesis and Reactions

2012

ISBN: 978-3-527-32944-1

Petrov, V. A.

Fluorinated Heterocyclic Compounds

Synthesis, Chemistry, and Applications

2009

ISBN: 978-0-470-45211-0

Ojima, I. (ed.)

Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology

2009

ISBN: 978-1-4051-6720-8

Mohr, F. (ed.)

Gold Chemistry

Applications and Future Directions in the Life Sciences

2009

ISBN: 978-3-527-32086-8

The Author

Prof. Dr. Peer Kirsch

Merck KGaA

Liquid Crystals R&D Chemistry

Frankfurter Str. 250

64293 Darmstadt

Germany

All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and publisher do not warrant the information contained in these books, including this book, to be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in mind that statements, data, illustrations, procedural details or other items may inadvertently be inaccurate.

Library of Congress Card No.: applied for

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <http://dnb.d-nb.de>.

© 2013 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany

All rights reserved (including those of translation into other languages). No part of this book may be reproduced in any form — by photoprinting, microfilm, or any other means — nor transmitted or translated into a machine language without written permission from the publishers. Registered names, trademarks, etc. used in this book, even when not specifically marked as such, are not to be considered unprotected by law.

Print ISBN: 978-3-527-33166-6

ePDF ISBN: 978-3-527-65138-2

ePub ISBN: 978-3-527-65137-5

mobi ISBN: 978-3-527-65136-8

oBook ISBN: 978-3-527-65135-1

To Annette and Alexander

“The fury of the chemical world is the element fluorine. It exists peacefully in the company with calcium in fluorspar and also in a few other compounds; but when isolated, as it recently has been, it is a rabid gas that nothing can resist.”

Scientific American, April 1888.

“Fluorine leaves nobody indifferent; it inflames emotions be that affections or aversions. As a substituent, it is rarely boring, always good for a surprise, but often completely unpredictable.”

M. Schlosser, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1496–1513.

Preface to the Second Edition

Within the few years since the first edition, the landscape of fluorine chemistry has changed dramatically: it is no longer the domain of a highly specialized (and often quite courageous) community, but the field has attracted the attention of mainstream organic and bioorganic chemists. The value of fluorine substitution in bioactive compounds and other functional materials has been widely recognized beyond the boundaries of the traditional fluorine chemistry community. Consequently, the variety of available synthetic methodology has exploded. A review with a reasonable degree of completeness has become impossible, and even the selection of the most significant developments is a very difficult task.

The scope of this book is not to offer a complete review of available methods, but to provide an introduction and a representative overview over the rapidly evolving field for the interested newcomer. It should be used as an entry point for a detailed in-depth study, but it is not intended as a stand-alone encyclopedia of fluorine chemistry. Therefore, there are many omissions, and the selection of the most interesting new developments has often been a matter of taste of the author.

The focus of the second edition is application fields where fluorine is essential for function, and also the chemistry needed to access such compounds. This applies not only to the material sciences but of course also to the biomedical field. On the synthetic side, the most remarkable new development is a huge variety of transition metal-catalyzed methods for the introduction of fluorine and fluorinated groups.

From the conceptual side, the author's choice of the most important new developments has been covered. From the application side, two new areas have been added: fluorinated dyes as one of the first areas of the industrial application of fluorine chemistry was recognized as a gap in the previous edition. In the last 10 years, the field of organic electronics has developed tremendously, and also here fluorine chemistry has found a very specific range of applications. A short review of the role and function of fluorine chemistry in this rapidly developing field has been added.

The author would like to thank the friends and colleagues who have provided their help and valuable input during the update of the text. In particular, Matthias Bremer, Alois Haas, Ingo Krossing, David O'Hagan, Gerd Röschenthaler, Georg Schulz, Peter and Marina Wanczek, John Welch, and Yurii Yagupolskii supported my project with information and critical discussions. From Wiley-VCH, Anne Brennführer and Lesley Belfit provided me with steady support and encouragement. Most of all, I owe my gratitude to my wife Annette and my son Alexander, who received much less attention than they deserved and who provided an environment where I could make the time for writing a book on top of many other things.

Seeheim-Jugenheim

Peer Kirsch

January 2013

Preface to the First Edition

The field of fluoroorganic chemistry has grown tremendously in recent years, and fluorochemicals have permeated nearly every aspect of our daily lives. This book is aimed at the synthetic chemist who wants to gain a deeper understanding of the fascinating implications of including the highly unusual element fluorine in organic compounds.

The idea behind this book was to introduce the reader to a wide range of synthetic methodology, based on the mechanistic background and the unique chemical and physicochemical properties of fluoroorganic compounds. There are quite some barriers to entering the field of preparative fluoroorganic chemistry, many based on unfounded prejudice. To reduce the threshold to practical engagement in fluoroorganic chemistry, I include some representative synthetic procedures which can be performed with relatively standard laboratory equipment.

To point out what can be achieved by introducing fluorine into organic molecules, a whole section of this book is dedicated to selected applications. Naturally, because of the extremely wide range of sometime highly specialized applications, this part had to be limited to examples which have gained particular importance in recent years. Of course, this selection is influenced strongly by the particular “taste” of the author.

I could not have completed this book without help and support from friends and colleagues. I would like to thank my colleagues at Merck KGaA, in particular Detlef Pauluth for his continuous support of my book project, and Matthias Bremer and Oliver Heppert for proof reading and for many good suggestions and ideas how to improve the book. The remaining errors are entirely my fault. G. K. Surya Prakash, Karl O. Christe, and David O'Hagan not only gave valuable advice but also provided me with literature. Gerd-Volker Röschenthaler, Günter Haufe, and Max Lieb introduced me to the fascinating field of fluorine chemistry. Andrew E. Feiring and Barbara Hall helped me to obtain historical photographs. Elke Maase from Wiley-VCH accompanied my work with continuous support and encouragement.

In the last 18 months I have spent most of my free time working on this book and not with my family. I would, therefore, like to dedicate this book to my wife Annette and my son Alexander.

Darmstadt

Peer Kirsch

May 2004

Abbreviations

| acac | Acetylacetonate ligand |

| aHF | Anhydrous hydrofluoric acid |

| AIBN | Azobis(isobutyronitrile) |

| AM | Active matrix |

| ASV | “Advanced super-V” |

| ATPH | Aluminum tri[2,6-bis(tert-butyl)phenoxide] |

| BAST | N,N-Bis(methoxyethyl)amino sulfur trifluoride |

| BINOL | 1,1′-Bi-2-naphthol |

| Boc | tert-Butoxycarbonyl protecting group |

| Bop-Cl | Bis(2-oxo-3-oxazolidinyl)phosphinic chloride |

| BSSE | Basis set superposition error |

| BTF | Benzotrifluoride |

| CFC | Chlorofluorocarbon |

| COD | Cyclooctadiene |

| CSA | Camphorsulfonic acid |

| Cso | Camphorsulfonyl protecting group |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| cVHP | Chicken villin headpiece subdomain |

| DABCO | Diazabicyclooctane |

| DAM | Di(p-anisyl)methyl protecting group |

| DAST | N,N-Diethylamino sulfur trifluoride |

| DBH | 1,3-Dibromo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin |

| DBPO | Dibenzoyl peroxide |

| DEAD | Diethyl azodicarboxylate |

| DCC | Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide |

| DCEH | Dicarboxyethoxyhydrazine |

| DEC | N,N-Diethylcarbamoyl protecting group |

| DFI | 2,2-Difluoro-1,3-dimethylimidazolidine |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| DIP-Cl | β-Chlorodiisopinocampheylborane |

| DMAc | N,N-Dimethylacetamide |

| DMAP | 4-(N,N-Dimethylamino)pyridine |

| DME | 1,2-Dimethoxyethane |

| DMF | N,N-Dimethylformamide |

| DMS | Dimethyl sulfide |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DSM | Dynamic scattering mode |

| DTBP | Di-tert-butyl peroxide |

| dTMP | Deoxythymidine monophosphate |

| dUMP | Deoxyuridine monophosphate |

| ECF | Electrochemical fluorination |

| ED | Effective dose |

| EPSP | 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate |

| ETFE | Poly(ethylene-co-tetrafluoroethylene) |

| FAR | α-Fluorinated alkylamine reagents |

| FDA | Fluorodeoxyadenosine |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FET | Field effect transistor |

| FFS | Fringe field switching |

| FITS | Perfluoroalkyl phenyl iodonium trifluoromethylsulfonate reagents |

| FRPSG | Fluorous reversed-phase silica gel |

| FSPE | Fluorous solid-phase extraction |

| F-TEDA | N-Fluoro-N′-chloromethyldiazoniabicyclooctane reagents |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HFCF | Hydrofluorocarbon |

| HFC | Hydrofluorocarbon |

| HFP | Hexafluoropropene |

| HMG+ | Hexamethylguanidinium cation |

| HMPA | Hexamethylphosphoric acid triamide |

| HSAB | Hard and soft acids and bases (Pearson concept) |

| IPS | In-plane switching |

| ITO | Indium tin oxide |

| LC | 1. Liquid crystal |

| 2. Lethal concentration | |

| LCD | Liquid crystal display |

| LD | Lethal dose |

| LDA | Lithium diisopropylamide |

| MCPBA | m-Chloroperbenzoic acid |

| MEM | Methoxyethoxymethyl protecting group |

| MOM | Methoxymethyl protecting group |

| MOST | Morpholino sulfur trifluoride |

| MVA | Multi-domain vertical alignment |

| NAD+/NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, oxidized/reduced form |

| NADP+/NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, oxidized/reduced form |

| NBS | N-Bromosuccinimide |

| NCS | N-Chlorosuccinimide |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| NFPy | N-Fluoropyridinium tetrafluoroborate |

| NFTh | N-Fluoro-o-benzenedisulfonimide |

| NIS | N-Iodosuccinimide |

| NLO | Nonlinear optics |

| NMP | N-Methylpyrrolidone |

| NPSP | N-Phenylselenylphthalimide |

| OD | Ornithine decarboxylase |

| ODP | Ozone-depleting potential |

| OFET | Organic field effect transistor |

| OLED | Organic light-emitting diode |

| OPV | Organic photovoltaics |

| OTFT | Organic thin-film transistor |

| PCH | Phenylcyclohexane |

| PCTFE | Polychlorotrifluoroethylene |

| PDA | Personal digital assistant |

| PET | 1. Positron emission tomography |

| 2. Poly(ethylene terephthlate) | |

| PFA | Perfluoropolyether |

| PFC | Perfluorocarbon |

| PFMC | Perfluoro(methylcyclohexane) |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOB | Perfluoro-n-octyl bromide |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctylsulfonic acid |

| phen | Phenanthroline |

| PI | Polyimide |

| PIDA | Phenyliodonium diacetate |

| pip+ | 1,1,2,2,6,6-Hexamethylpiperidinium cation |

| PLP | Pyridoxal phosphate |

| PNP | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase |

| PPVE | Poly(heptafluoropropyl trifluorovinyl ether) |

| PTC | Phase transfer catalysis |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene (TeflonTM) |

| PVDF | Poly(vinylidene difluoride) |

| PVPHF | Poly(vinylpyridine) hydrofluoride |

| P3DT | Poly(3-dodecylthiophene) |

| QM/MM | Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics |

| QSAR | Quantitative structure–activity relationships |

| SAH | S-Adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase |

| SAM | 1. S-Adenosylmethionine |

| 2. Self-assembled monolayer | |

| SBAH | Sodium bis(methoxyethoxy)aluminum hydride |

| scCO2 | Supercritical carbon dioxide |

| SFC | Supercritical fluid chromatography |

| SET | Single electrton transfer |

| SFM | Superfluorinated material |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| STN | Super-twisted nematic |

| TADDOL | α,α,α′,α′-Tetraaryl-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolane-4,5-dimethanol |

| TAS+ | Tris(dimethylamino)sulfonium cation |

| TASF | Tris(dimethylamino)sulfonium difluorotrimethylsiliconate, (Me2N)3S+ Me3SiF2− |

| TBAF | Tetrabutylammonium fluoride |

| TBDMS | tert-Butyldimethylsilyl protecting group |

| TBS | See TBDMS |

| TBTU | O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate |

| TDAE | Tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxide |

| TFT | Thin film transistor |

| THF | 1. Tetrahydrofuran |

| 2. Tetrahydrofolate coenzyme | |

| THP | Tetrahydropyranyl protecting group |

| TIPS | Triisopropylsilyl protecting group |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| TMS | Trimethylsilyl protecting group |

| TN | Twisted nematic |

| TPP | Triphenylphosphine |

| TPPO | Triphenylphosphine oxide |

| TR | Trypanothione reductase |

| VHR | Voltage holding ratio |

| ZPE | Zero point energy |

1

Introduction

Fluorine is the element of extremes, and many fluorinated organic compounds exhibit extreme and sometimes even bizarre behavior. A large number of polymers, liquid crystals, and other advanced materials owe their unique property profile to the influence of fluorinated structures.

Fluoroorganic compounds are almost completely foreign to the biosphere. No central biological processes rely on fluorinated metabolites. Many modern pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, on the other hand, contain at least one fluorine atom, which usually has a very specific function. Perfluoroalkanes, especially, can be regarded as “orthogonal” to life – they can assume a purely physical function, for example, oxygen transport, but are foreign to the living system to such an extent that they are not recognized and are completely ignored by the body.

Although fluorine itself is the most reactive of all elements, some fluoroorganic compounds have chemical inertness like that of the noble gases. They sometimes cause ecological problems not because of their reactivity but because of the lack of it, making them persistent in Nature on a geological time scale.

All these points render fluoroorganic chemistry a highly unusual and fascinating field [1–14], providing surprises and intellectual stimulation in the whole range of chemistry-related sciences, including theoretical, synthetic, and biomedical chemistry and materials science.

Because of the hazardous character of hydrofluoric acid and the difficult access to elemental fluorine itself, the development of organofluorine chemistry and the practical use of fluoroorganic compounds started relatively late in the nineteenth century (Table 1.1). The real breakthrough was the first synthesis of elemental fluorine by Henri Moissan in 1886 [15], but the first defined fluoroorganic compound, benzoyl fluoride, had already been prepared and described by the Russian chemist, physician, and composer Alexander Borodin in 1863 [16].

Table 1.1 Dates and historical key events in the development of fluoroorganic chemistry.

| Time | Key event |

| 1764 | First synthesis of hydrofluoric acid from fluorspar and sulfuric acid by A. S. Marggraf, repeated in 1771 by C. Scheele |

| 1863 | Synthesis of benzoyl fluoride as the first fluoroorganic compound by A. Borodin |

| 1886 | First synthesis of elemental fluorine by H. Moissan (Nobel Prize in 1906) by electrolysis of an HF–KF system |

| 1890s | Beginning of halofluorocarbon chemistry by direct fluorination (H. Moissan) and Lewis acid-catalyzed halogen exchange (F. Swarts) |

| 1920s | Access to fluoroarenes by the Balz–Schiemann reaction |

| 1930s | Refrigerants (Freon, in Germany Frigen), fire extinguishing chemicals (Halon), aerosol propellants. Fluorinated dyes with enhanced color fastness. |

| 1940s | Polymers (PTFE = Teflon), electrochemical fluorination (H. Simons) |

| 1941–1954 | Manhattan Project: highly resistant materials for isotope separation plants, lubricants for gas centrifuges, and coolants |

| 1950s | Fluoropharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, artificial blood substitutes, respiratory fluids, and chemical weapons |

| 1980s | Gases for plasma etching processes and cleaning fluids for the semiconductor industry |

| 1987 | The Montreal Protocol initiates the phasing-out of CFCs |

| 1990s | Fluorinated liquid crystals for active matrix liquid crystal displays (AM-LCDs) |

| 2000s | Fluorinated photoresists for the manufacture of integrated electronic circuits by 157 nm photolithography |

Industrial application of fluorinated organic compounds started at the beginning of the 1930s with the introduction of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as refrigerants [17]. The major turning point in the history of industrial fluoroorganic chemistry was the beginning of the Manhattan Project for development of nuclear weapons in 1941 [18]. The Manhattan Project triggered the need for highly resistant materials, lubricants, and coolants and the development of technology for handling extremely corrosive fluoroinorganic compounds. The consumption of hydrofluoric acid as the main precursor of all these materials soared, accordingly, during the 1940s. After 1945, with the beginning of the Cold War, various defense programs provided a constant driving force for further development of the chemistry and use of organofluorine compounds. In the 1950s and 1960s, more civilian applications of fluorinated pharmaceuticals and materials moved to the forefront [19].

The prediction of the ozone-depleting effect of CFCs in 1974 [20] and the subsequent occurrence of the hole in the ozone layer over the Antarctic in 1980 enforced a drastic reorientation of industrial fluoroorganic chemistry. With the Montreal Protocol in 1987, the phasing-out of most CFCs was initiated. Some of the refrigerants and cleaning chemicals could be replaced by other fluorine-containing chemicals (for example, hydrofluorocarbons, HFCs and fluorinated ethers), but in general the fluorochemical industry had to refocus on other fields of application, for example, fluoropolymers, fluorosurfactants, and fluorinated intermediates for pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals [19]. A major and rapidly growing market segment is fluorine-containing fine chemicals for use as intermediates in pharmaceuticals and agrochemistry. Another application in which fluorochemicals have started to play an increasingly dominant role in the last few years is the electronics industry. Relevant compounds include plasma etching gases, cleaning fluids, specialized fluoropolymers, fluorinated photoresists for manufacturing integrated circuits by the currently emerging 157 nm photolithography, and liquid crystals for application in liquid crystal displays (LCDs).

Naturally occurring fluorine is composed of the pure  isotope. Its relative abundance in the Earth's crust as a whole is 0.027% by weight (for comparison, that of Cl is 0.19% and that of Br is 6 × 10−4% by weight). Because of the extremely low solubility (solubility product 1.7 × 10−10 at 298 K) of its most important mineral, fluorspar (CaF2), the concentration of fluoride in seawater is very low (about 1.4 mg l−1) [21].

isotope. Its relative abundance in the Earth's crust as a whole is 0.027% by weight (for comparison, that of Cl is 0.19% and that of Br is 6 × 10−4% by weight). Because of the extremely low solubility (solubility product 1.7 × 10−10 at 298 K) of its most important mineral, fluorspar (CaF2), the concentration of fluoride in seawater is very low (about 1.4 mg l−1) [21].

The most abundant natural sources of fluorine are the minerals fluorspar and cryolite (Na3AlF6). Fluorapatite [Ca5(PO4)3F = “3Ca3(PO4)2·CaF2”] is, with hydroxyapatite [Ca5(PO4)3OH], a major component of tooth enamel, giving it its extreme mechanical strength and life-long durability. Minor quantities of hydrogen fluoride, fluorocarbons, and even polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are released by volcanoes [22]. Even elemental fluorine (F2) occurs in Nature, as an inclusion in fluorspar (about 0.46 mg of F2 per gram of CaF2). The so-called “stinkspar” or “antozonite,” which has been irradiated with γ-radiation from uranium ore, releases a pungent smell on rubbing or crushing [23].

Despite the relatively high abundance of fluorine in the lithosphere, only very few fluoroorganic metabolites have been identified in the biosphere [24]. No central metabolic process depending essentially on fluorine is yet known. It might be speculated that the reason for this unexpected phenomenon is the poor solubility of CaF2, with Ca2+ ions being one of the central components essential for the existence of any living organism. Another reason might also be the very high hydration enthalpy of the small fluoride anion, which limits its nucleophilicity in aqueous media by requiring an energetically demanding dehydration step before any reaction as a nucleophile [24].

Hydrofluoric acid is the most basic common precursor of most fluorochemicals. Aqueous hydrofluoric acid is prepared by reaction of sulfuric acid with fluorspar (CaF2). Because HF etches glass with the formation of silicon tetrafluoride, it must be handled in platinum, lead, copper, Monel (a Cu–Ni alloy developed during the Manhattan Project), or plastic (e.g., polyethylene or PTFE) apparatus. The azeotrope contains 38% w/w HF and it is a relatively weak acid (pKa 3.18, 8% dissociation), comparable to formic acid. Other physicochemical properties of hydrofluoric acid are listed in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Physicochemical properties of hydrofluoric acid [25] (the vapor pressure and density correspond to a temperature of 0 °C).

| Property | Anhydrous HF | 40% HF–H2O |

| Boiling point (°C) | 19.5 | 111.7 |

| Melting point (°C) | −83.4 | −44.0 |

| HF vapor pressure (Torr) | 364 | 21 |

| Density (g cm−3) | 1.015 | 1.135 |

Anhydrous hydrofluoric acid (aHF) is obtained by heating Fremi's salt (KF·HF) as a liquid, boiling at 19.5 °C. Similarly to water, aHF has a liquid range of ∼100 °C and a dielectric constant  of 83.5 (at 0 °C). Associated by strong hydrogen bonding, it forms oligomeric (HF)n chains with a predominant chain length n of 6–7 HF units[25]b. In contrast with aqueous HF, pure aHF is a very strong acid, slightly weaker than sulfuric acid. Like water, aHF undergoes autoprotolysis with an ion product c(FHF−) × c(HFH+) of 10−10.7 at 0 °C. In combination with strong Lewis acids, for example, as AsF5, SbF5, or SO3, aHF forms some of the strongest known protic acids. The best known example is “magic acid” (FSO3H–SbF5), which can protonate and crack paraffins to give tert-butyl cations [25]. Apart from its use as a reagent, aHF is also an efficient and electrochemically inert solvent for a variety of inorganic and organic compounds.

of 83.5 (at 0 °C). Associated by strong hydrogen bonding, it forms oligomeric (HF)n chains with a predominant chain length n of 6–7 HF units[25]b. In contrast with aqueous HF, pure aHF is a very strong acid, slightly weaker than sulfuric acid. Like water, aHF undergoes autoprotolysis with an ion product c(FHF−) × c(HFH+) of 10−10.7 at 0 °C. In combination with strong Lewis acids, for example, as AsF5, SbF5, or SO3, aHF forms some of the strongest known protic acids. The best known example is “magic acid” (FSO3H–SbF5), which can protonate and crack paraffins to give tert-butyl cations [25]. Apart from its use as a reagent, aHF is also an efficient and electrochemically inert solvent for a variety of inorganic and organic compounds.

The dark side of hydrofluoric acid is its toxicity and corrosiveness. Aqueous and anhydrous HF readily penetrate the skin and, because of its locally anesthetizing effect, even in very small quantities, it can cause deep lesions and necroses [26, 27]. An additional health hazard is the systemic toxicity of fluoride ions, which interfere strongly with calcium metabolism. Resorption of HF by skin contact (from a contact area exceeding 160 cm2), inhalation, or ingestion leads to hypocalcemia with very serious consequences, for example, cardiac arrhythmia.

The most effective, specific antidote to HF and inorganic fluorides is calcium gluconate, which acts by precipitating fluoride ions as insoluble CaF2. After inhalation of HF vapor, treatment of the patient with dexamethasone aerosol is recommended, to prevent pulmonary edema. Even slight contamination with HF must always be taken seriously, and after the necessary first-aid measures a physician should be consulted as soon as possible.

It should also be kept in mind that some inorganic (e.g., CoF3) and organic fluorinated compounds (e.g., pyridine–HF, NEt3·3HF, N,N-diethylamino sulfur trifluoride (DAST)) can hydrolyze on contact with the skin and body fluids, liberating hydrofluoric acid with the same adverse consequences.

Nevertheless, when the necessary, relatively simple precautions are taken [26], hydrofluoric acid and its derivatives can be handled safely and with minimum risk to health.

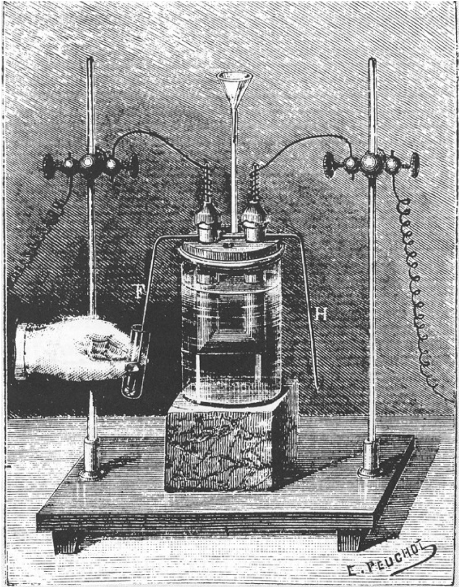

Despite the ubiquitous occurrence of fluorides in Nature, elemental fluorine itself proved to be quite elusive. Because of its very high redox potential (approximately +3 V, depending on the pH of aqueous systems), chemical synthesis from inorganic fluorides was impeded by the lack of a suitable oxidant. Therefore, Moissan's first synthesis of fluorine in 1886 by electrolysis of a solution of KF in aHF in a platinum apparatus [28, 29] was a significant scientific breakthrough, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1906 for his discovery (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The apparatus used by Moissan for the first isolation of elemental fluorine by electrolysis of an HF–KF system in 1886 [28].

Fluorine is a greenish yellow gas, melting at −219.6 °C and boiling at −188.1 °C. It has a pungent smell reminiscent of a mixture of chlorine and ozone and is perceptible even at a concentration of 10 ppm. It is highly toxic and extremely corrosive, especially towards oxidizable substrates. Most organic compounds spontaneously combust or explode on contact with undiluted fluorine at ambient pressure. Because of its high reactivity, fluorine reacts with hot platinum and gold, and even with the noble gases krypton and xenon. In contrast to hydrofluoric acid, dry fluorine gas does not etch glassware. Because of its extreme reactivity and hazardous nature, for many chemical transformations fluorine is diluted with nitrogen (typically 10% F2 in N2). In this form, the gas can be stored without undue risk in passivated steel pressure bottles. Reactions can be conducted either in glassware or in fluoropolymer (PTFE or perfluoropolyether (PFA)) apparatus. If some elementary precautions are taken (for details, see Appendix A), reactions with nitrogen-diluted fluorine can be conducted safely in an ordinarily equipped laboratory.

Fluorine owes its unparalleled reactivity, on the one hand, to the ease of its homolytic dissociation into radicals (only 37.8 kcal mol−1, compared with 58.2 kcal mol−1 for Cl2) and, on the other hand, to its very high redox potentials of +3.06 and +2.87 V in acidic and basic aqueous media, respectively [30].

Fluorine, as the most electronegative element (electronegativity 3.98) [31], occurs in its compounds exclusively in the oxidation state −1. The high electron affinity (3.448 eV), extreme ionization energy (17.418 eV), and other unique properties of fluorine can be explained by its special location in the periodic system as the first element with p orbitals able to achieve a noble gas electron configuration (Ne) by uptake of one additional electron. For the same reason, the fluoride ion is also the smallest (ion radius 133 pm) and least polarizable anion. These very unusual characteristics are the reason why fluorine or fluorine-containing nonpolarizable anions can stabilize many elements in their highest and otherwise inaccessible oxidation states (e.g., IF7, XeF6, KrF2, O2+PtF6−, N5+AsF6−).

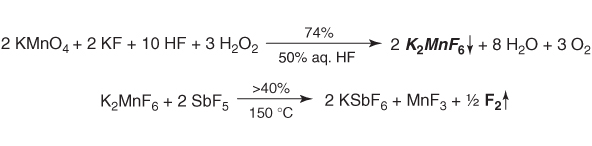

A purely chemical synthesis of elemental fluorine was achieved by K. O. Christe in 1986 [32] (Scheme 1.1), just in time for the 100th anniversary of Moissan's first electrochemical fluorine synthesis. Nevertheless, in his paper Christe remarked that all the basic know-how required for this work had already been available 50 years earlier. The key to his simple method is a displacement reaction between potassium hexafluoropermanganate [33] and the strongly fluorophilic Lewis acid antimony pentafluoride at 150 °C.

Scheme 1.1 The first “chemical” synthesis of fluorine [32].

Nowadays, industrial fluorine production is based on Moissan's original method [21]. In the so-called “middle-temperature method,” a KF·2HF melt is electrolyzed at 70–130 °C in a steel cell. The steel cell itself is used as the cathode; the anodes are specially treated carbon blocks (Söderberg electrodes). The voltage used is 8–12 V per cell [34]. During the Cold War, the major use of elemental fluorine was in the production of uranium hexafluoride for separation of the 235U isotope. Nowadays, the production of nuclear weapons has moved into the background and large quantities of fluorine are used for preparation of chemicals for the electronics industry [for example, WF6 for CVD (chemical vapor deposition), SF6, NF3, and BrF3 as etching gases for semiconductor production, and graphite fluorides as cathode materials in primary lithium batteries] and for making inert polyethylene gasoline tanks in the automobile industry.

Fluoroorganic and, especially, perfluorinated compounds are characterized by a unique set of unusual and sometimes extreme physical and chemical properties. These are utilized in a variety of different applications ranging from pharmaceutical chemistry to materials science [35].

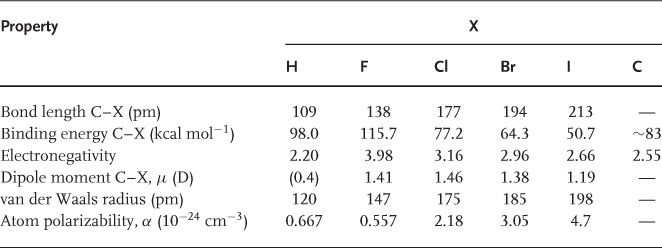

The physical properties of fluoroorganic compounds are governed by two main factors: (i) the combination of high electronegativity with moderate size and the excellent match between the fluorine 2s or 2p orbitals with the corresponding orbitals of carbon and (ii) the resulting extremely low polarizability of fluorine [36].

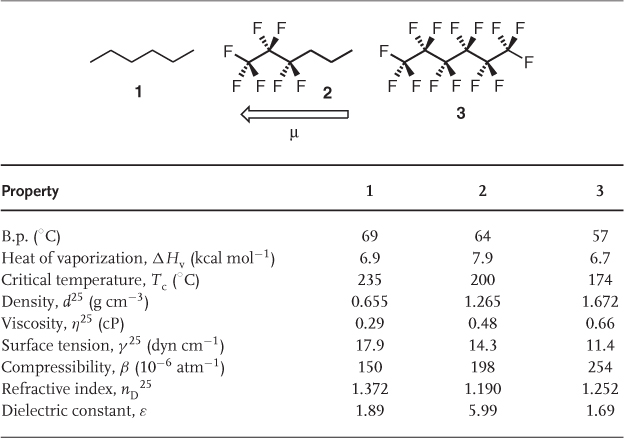

Fluorine has the highest electronegativity of all the elements (3.98) [31], rendering the carbon–fluorine bond highly polar with a typical dipole moment of around 1.4 D, depending on the exact chemical environment (Table 1.3). The apparently contradictory observation that perfluorocarbons (PFCs) are among the most nonpolar solvents in existence [e.g.,  = 1.69 for C6F14 (3) compared with 1.89 for C6H14 (1); Table 1.4 can be explained by the fact that all local dipole moments within the same molecule cancel each other, leading in total to a nonpolar compound. In semifluorinated compounds, for example, 2, in which some local dipole moments are not compensated, the effects of the resulting overall dipole moment are mirrored by their physicochemical properties, especially their heats of vaporization (ΔHv) and their dielectric constants (

= 1.69 for C6F14 (3) compared with 1.89 for C6H14 (1); Table 1.4 can be explained by the fact that all local dipole moments within the same molecule cancel each other, leading in total to a nonpolar compound. In semifluorinated compounds, for example, 2, in which some local dipole moments are not compensated, the effects of the resulting overall dipole moment are mirrored by their physicochemical properties, especially their heats of vaporization (ΔHv) and their dielectric constants ( ).

).

Table 1.3 Comparison of the characteristics of carbon–halogen and carbon–carbon bonds (electronegativities from Ref. [31]; van der Waals radii from Ref. [37]; atom polarizabilities from Ref. [38]).

Table 1.4 Comparison of selected physicochemical properties of n-hexane (1) and its perfluorinated (3) and semifluorinated (2) analogs [36].

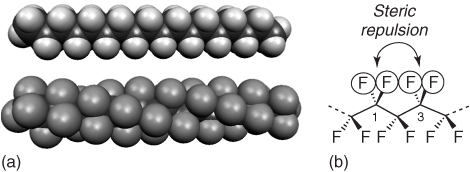

The low polarizability and the slightly larger size of fluorine compared with hydrogen (23% larger van der Waals radius) also have consequences for the structure and molecular dynamics of PFCs. Linear hydrocarbons have a linear zigzag conformation (Figure 1.2). PFCs, in contrast, have a helical structure, because of the steric repulsion of the electronically “hard” fluorine substituents bound to carbon atoms in the relative 1,3-positions. Whereas the hydrocarbon backbone has some conformational flexibility, PFCs are rigid, rod-like molecules. This rigidity can be attributed to repulsive stretching by the 1,3-difluoromethylene groups.

Figure 1.2 The zigzag conformation of octadecane (a) compared with the helical perfluorooctadecane (b), modeled at the PM3 level of theory [39, 40].

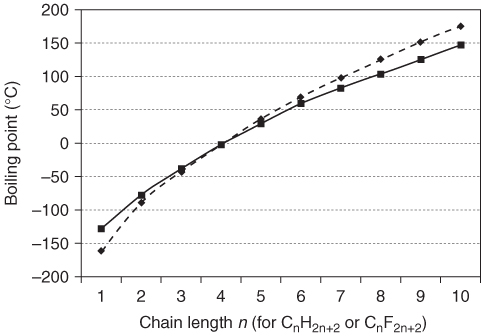

Another consequence of the low polarizability of PFCs is very weak intermolecular dispersion interactions. A striking characteristic of PFCs is their very low boiling points, compared with hydrocarbons of similar molecular mass. For example, n-hexane and CF4 have about the same molecular mass (Mr 86 and 88 g mol−1, respectively), but the boiling point of CF4 (−128 °C) is nearly 200 °C lower than that of n-hexane (69 °C). If the homologous hydrocarbons and PFCs are compared (Figure 1.3), it is apparent they have very similar boiling points, even though the molecular mass of the PFCs is about four times higher than that of the corresponding hydrocarbons.

Figure 1.3 The boiling points of homologous alkanes ( ) compared with those of the corresponding perfluoroalkanes (

) compared with those of the corresponding perfluoroalkanes ( ) [36].

) [36].

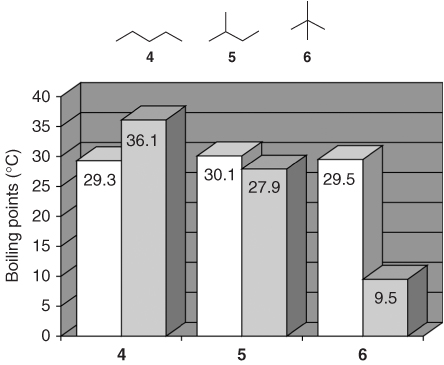

In contrast to typical hydrocarbon systems, branching has a negligible effect on the boiling points of PFCs (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Boiling points of linear and branched isomers of perfluoropentane (white bars) and pentane (gray bars) [36].

Perfluorinated amines, ethers, and ketones usually have much lower boiling points than their hydrocarbon analogs.

An interesting fact is that the boiling points of PFCs are only 25–30 °C higher than those of noble gases of similar molecular mass (Kr, Mr 83.8 g mol−1, b.p. −153.4 °C; Xe, Mr 131.3 g mol−1, b.p. −108.1 °C; and Rn, Mr 222 g mol−1, b.p. −62.1 °C). In other aspects also, for example, their limited chemical reactivity, PFCs resemble the noble gases.

Another consequence of the low polarizability of PFCs is the occurrence of large miscibility gaps in solvent systems composed of PFCs and hydrocarbons. The occurrence of a third, “fluorous,” liquid phase in addition to the “organic” and “aqueous” phases has been extensively exploited in the convenient and supposedly ecologically benign “fluorous” chemistry, which is discussed in detail in Sections 6 and 7.

Another very prominent characteristic resulting from their weak intermolecular interaction is the extremely low surface tension (γ) of the perfluoroalkanes. They have the lowest surface tensions of any organic liquids (an example is given in Table 1.4) and therefore wet almost any surface [36].

Solid PFC surfaces also have extremely low surface energies (γc). Thus, PTFE (Teflon) has a γc value of 18.5 dyn cm−1, which is the reason for the anti-stick and low-friction properties used for frying pans and other applications. That this effect is directly related to the fluorine content becomes obvious on comparison of the surface energies of poly(difluoroethylene) (25 dyn cm−1), poly(fluoroethylene) (28 dyn cm−1), and polyethylene (31 dyn cm−1). If only one fluorine atom in PTFE is replaced by more polarizable chlorine, the surface energy of the resulting poly(chlorotrifluoroethylene) jumps to 31 dyn cm−1, the same value as for polyethylene [41].

The decisive aspect of achieving low surface energies seems to be a surface which is densely covered by fluorine atoms. Accordingly, the lowest surface energies of any material observed are those of fluorinated graphites (C2F)n and (CF)n, ∼6 dyn cm−1 [42]. Monolayers of perfluoroalkanoic acids CF3(CF2)nCOOH also have surface energies ranging between 6 and 9 dyn cm−1 if n ≥ 6 [41b]. The same effect is observed for alkanoic acids containing only a relatively short perfluorinated segment [at least CF3(CF2)6] at the end of their alkyl chain, which is then displayed at the surface.

When a hydrophilic functional group is attached to a PFC chain, the resulting fluorosurfactants (e.g., n-CnF2n + 1COOLi, with n ≥ 6) can reduce the surface tension of water from 72 to 15–20 dyn cm−1 compared with 25–35 dyn cm−1 for analogous hydrocarbon surfactants [43].

Most unusual types of surfactant are the so-called diblock amphiphiles F(CF2)m(CH2)nH, which have both hydrocarbon and PFC moieties. At the interface between an organic and a “fluorous” phase (e.g., a liquid PFC), they show the behavior of typical surfactants [44], for example, micelle formation.

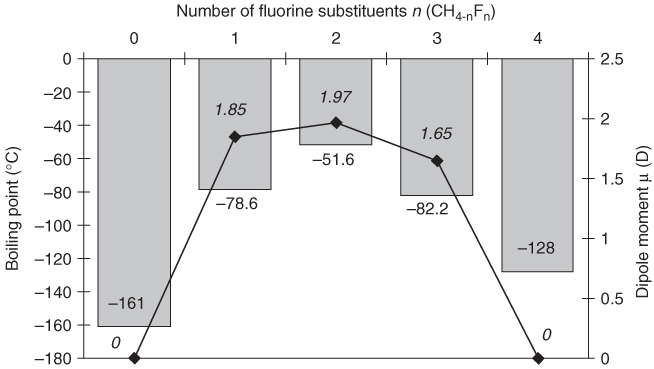

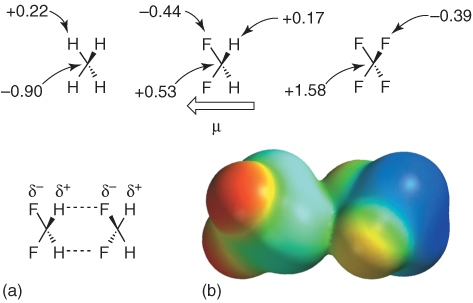

Whereas intermolecular interactions between perfluoroalkanes are very weak, fairly strong electrostatic interactions are observed for some partially fluorinated hydrocarbons (HFCs), because of local, noncompensated carbon–fluorine dipole moments. The most pronounced effects of this kind are observed when bonds to fluorine and hydrogen arise from the same carbon atom. In such circumstances, the polarized C–H bonds can act as hydrogen-bond donors with the fluorine as the acceptor. The simplest example of this effect is difluoromethane. If the boiling points of methane and the different fluoromethanes are compared (Figure 1.5), the nonpolar compounds CH4 and CF4 are seen to have the lowest boiling points; the more polar compounds CH3F and CHF3 boil at slightly higher temperatures. The maximum is for CH2F2, which has the strongest molecular dipole moment and which can – at least in principle – form a three-dimensional hydrogen-bond network similar to that of water with the C–H bonds acting as the hydrogen-bond donors and C–F bonds as the acceptors (Figure 1.6) [45].

Figure 1.5 Boiling points (gray bars) and dipole moments (D) ( , numerical values in italics) of methane and the different fluoromethanes CH4 – nFn [36].

, numerical values in italics) of methane and the different fluoromethanes CH4 – nFn [36].

Figure 1.6 (a) Comparison of the distribution of natural partial charges q (e) on CH4, CH2F2, and CF4 (MP2/6–31+G** level of theory) [46] and (b) the calculated structure (AM1) of a doubly hydrogen-bridged difluoromethane dimer. The electrostatic potential (red denotes negative and blue positive partial charges) is mapped on the electron isodensity surface [40].

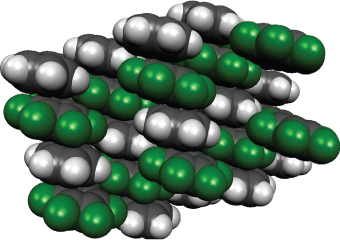

A different type of strong electrostatic interaction is observed between arenes and perfluoroarenes (a detailed discussion of this phenomenon can be found in Ref. [47]). Benzene (m.p. 5.5 °C; b.p. 80 °C) and hexafluorobenzene (m.p. 3.9 °C; b.p. 80.5 °C) are known to have very similar phase-transition temperatures. In contrast, an equimolar mixture of both compounds gives a crystalline 1:1 complex melting at 23.7 °C, which is about 19 °C higher than those of the individual components [48]. In contrast to C6H6 and C6F6, which crystallize in an edge-to-face, fishbone pattern, C6H6·C6F6 co-crystals contain both components in alternating, tilted parallel, and approximately centered stacks with an interlayer distance of about 3.4 Å and a centroid–centroid distance of about 3.7 Å (Figure 1.7). Neighboring stacks are slightly stabilized by additional lateral Caryl–H···F contacts [49].

Figure 1.7 X-ray crystal structure of the benzene–hexafluorobenzene 1:1 complex, measured at 30 K in the lowest-temperature modification [49b].

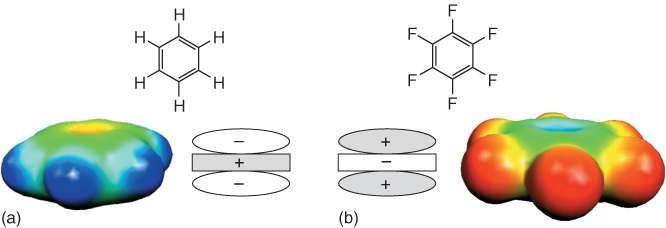

Similar structures have been observed for a variety of other arene–perfluoroarene complexes [47], indicating that this kind of interaction is a generally occurring phenomenon for this type of structure [50]. Evidence based on structural [49] and spectroscopic data [51] and on quantum chemical calculations [52] (Figure 1.8) indicates that the observed arene–perfluoroarene interactions are mainly the consequence of strong quadrupolar electrostatic attraction [53].

Figure 1.8 Schematic representation of the complementary quadrupole moments of benzene (a) (−29.0 × 10−40 C m−2) and hexafluorobenzene (b) (+31.7 × 10−40 C m−2) [53]. The color pictures show the electrostatic potentials mapped on the isodensity surfaces (B3LYP/6–31G* level of theory) [40, 46]. In benzene (far left), the largest negative charge density (coded in red) is located above and below the plane of the π-system. In contrast, in hexafluorobenzene, these locations carry a positive partial charge (coded in blue).

The usual interactions driving “aromatic stacking forces,” for example, dispersion interactions with a distance dependence of r−6, seem to play an additional major role in this phenomenon. The occurrence of a charge-transfer complex between electron-rich benzene and electron-deficient hexafluorobenzene can, on the other hand, be excluded by spectroscopic data. The quadrupole moments of benzene (−29.0 × 10−40 C m−2) and hexafluorobenzene (+31.7 × 10−40 C m−2) have a very similar order of magnitude but with their different signs the compounds form a complementary pair, interacting with a distance dependence of r−5. The directionality of the quadrupolar interaction is considered to be the main force driving preference for the sandwich-like arrangement of the complementary arenes in the solid state. Ab initio and density functional theory (DFT) calculations gave estimates between −3.7 and −5.6 kcal mol−1 (assuming an interplanar distance of 3.6 Å) for the interaction energy between a parallel, but slightly shifted heterodimer as found in the crystal structure. The interaction within the heterodimer was estimated to be 1.5–3 times stronger than within the corresponding benzene or hexafluorobenzene homodimers. Another interesting result from the calculations is that the contribution of the dispersion interactions to the overall binding energy of the heterodimer is even stronger than that of the electrostatic interaction.

Electrostatic interactions resulting from the polarity of the carbon–fluorine bond play an important role in the binding of fluorinated biologically active compounds to their effectors [54] (discussed in detail in Section 9) and for the mesophase behavior of fluorinated liquid crystals [55] (Section 8.4). The consequences of the low polarizability of perfluorinated molecular substructures have been put into commercial use for CFC refrigerants, fire-fighting chemicals, lubricants, polymers with anti-stick and low-friction properties, and fluorosurfactants.

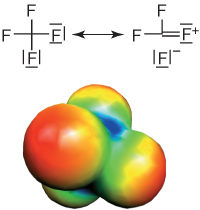

The most obvious characteristic of fluoroorganic compounds is the extreme stability of the carbon–fluorine bond [56]. The stability increases with increase in the number of fluorine substituents bound to the same carbon atom. This increase in stability is reflected in the lengths of the C–F bonds in the series CH3F (140 pm) > CH2F2 (137 pm) > CHF3 (135 pm) > CF4 (133 pm) [calculation at the MP2/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory] [46]. The main reason for this stabilization is the nearly optimum overlap between the fluorine 2s and 2p orbitals and the corresponding orbitals of carbon; this allows the occurrence of dipolar resonance structures for multiply fluorine-substituted carbon (Figure 1.9). The consequences for chemical reactivity of this “self-stabilization” of multiple fluorine substituents on the same carbon atom are discussed in more detail in Section 2.3.4.

Figure 1.9 Resonance stabilization of the carbon–fluorine bond in tetrafluoromethane, and electrostatic and steric shielding against nucleophilic attack on the central carbon atom. The electrostatic potentials are mapped on the electron isodensity surface (calculation at the MP2/6–31+G* level of theory [40, 46]; red denotes negative and blue positive partial charges).

In addition to this thermodynamic stabilization, in PFCs additional kinetic stability is derived from the steric shielding of the central carbon atom by a “coating” of fluorine substituents. The three tightly bound lone electron pairs per fluorine atom and the negative partial charges are an effective electrostatic and steric shield against any nucleophilic attack targeted against the central carbon atom.

PFCs are, therefore, extremely inert against basic hydrolysis. PTFE, for example, can even withstand the action of molten potassium hydroxide. At high temperatures, PFCs are attacked by strong Lewis acids, for example, aluminum chloride. In such reactions, decomposition is initiated by the removal of a fluoride ion from the fluorous “protection shield,” rendering the resulting carbocation open to nucleophilic attack. Another mode of degradation of PFCs is by strong reducing agents at elevated temperatures. Thus PFCs are decomposed on contact with molten alkali metals and also on contact with iron at 400–500 °C. The latter type of reaction has even been utilized for the industrial synthesis of perfluoroarenes by reductive aromatization of perfluorocycloalkanes (Section 2.4.2).

Because of its strongly negative inductive effect, fluorine substitution tends to increase dramatically the acidity of organic acids [57, 58] (Table 1.5). For example, the acidity of trifluoroacetic acid (pKa = 0.52) is four orders of magnitude higher than that of acetic acid (pKa = 4.76). Even very weak acids, for example, tert-butanol (pKa = 19.0), are converted by fluorination into moderately strong acids [(CF3)3COH, pKa = 5.4].

Table 1.5 Acidities (pKa) of organic acids in comparison with their fluorinated analogs [58].

| Acid | pKa |

| CH3COOH | 4.76 |

| CF3COOH | 0.52 |

| C6H5COOH | 4.21 |

| C6F5COOH | 1.75 |

| CH3CH2OH | 15.9 |

| CF3CH2OH | 12.4 |

| (CH3)2CHOH | 16.1 |

| (CF3)2CHOH | 9.3 |

| (CH3)3COH | 19.0 |

| (CF3)3COH | 5.4 |

| C6H5OH | 10.0 |

| C6F5OH | 5.5 |

The inductive effect of fluorination also reduces the basicity of organic bases by approximately the same order of magnitude (Table 1.6). In contrast with basicity, the nucleophilicity of amines is influenced much less by fluorinated substituents.

Table 1.6 Basicities (pKb) of organic bases in comparison with their fluorinated analogs [58].

| Base | pKb |

| CH3CH2NH2 | 3.3 |

| CF3CH2NH2 | 8.1 |

| C6H5NH2 | 9.4 |

| C6F5NH2 | 14.36 |

Other effects of fluorine substitution in organic compounds include a strong influence on lipophilicity and the ability of fluorine to participate in hydrogen bonding either as a hydrogen-bond acceptor or as an inductive activator of a hydrogen-bond donor group. This behavior has a substantial effect on the biological activity of fluorochemicals and is discussed in more detail in Section 4.5.

Despite or, better, because of their extreme chemical stability, PFCs and halofluorocarbons have a dramatic impact on the global environment; this was nearly impossible to predict when the substances were first introduced into industrial mass production and ubiquitous use.

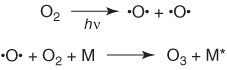

Because of their extreme stability against all kinds of aggressive chemical agents, for example, radicals, PFCs, and halofluorocarbons are not degraded in the lower layers of the atmosphere as are other pollutants. After several years, or even decades, they finally reach the stratosphere at altitudes of 20–40 km [59, 60]. In this layer, under the influence of short-wave UV irradiation, ozone is formed continuously (Scheme 1.2). This stratospheric ozone plays an essential role in preserving life on Earth by absorbing the short-wavelength UV radiation which would otherwise lead to an increase in photochemically induced mutations in most life forms. For humans, overexposure to short-wave UV irradiation results in a dramatically increased risk of skin cancer. Many crops and other plants also react rather sensitively towards an increase in UV exposure.

Scheme 1.2 Mechanism of ozone formation in the stratosphere [59]. Dioxygen is photochemically split into atomic oxygen, which adds to another dioxygen molecule. The excess energy from the recombination is carried away by a collision partner (M).

Figure 1.10