THE

CABARET

OF

PLANTS

RICHARD MABEY is one of our greatest nature writers. He is the author of some thirty books, including the bestselling plant bible Flora Britannica, Food for Free, Turned Out Nice Again, Weeds: the Story of Outlaw Plants and Nature Cure which was shortlisted for the Whitbread, Ondaatje and Ackerley Awards. His biography, Gilbert White, won the Whitbread Biography Award. A regular commentator on radio and in the national press, he was elected a Fellow in the Royal Society of Literature in 2012. He lives in Norfolk.

Also by Richard Mabey

The Perfumier and the Stinkhorn

Turned Out Nice Again

Weeds

Food for Free

The Unofficial Countryside

The Common Ground

The Flowering of Britain

Gilbert White

Home Country

Whistling in the Dark: In Pursuit of the Nightingale

Flora Britannica

Selected Writing 1974–1999

Nature Cure

Fencing Paradise

Beechcombings

A Brush with Nature

Dreams of the Good Life: The Life of Flora Thompson and the Creation of Lark Rise to Candleford

THE

CABARET

OF

PLANTS

BOTANY AND THE IMAGINATION

RICHARD MABEY

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Richard Mabey, 2015

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 401 4

for Vivien

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age …

Dylan Thomas

Contents

Introduction: The Vegetable Plot

HOW TO SEE A PLANT

1. Symbols from the Ice: Plants as Food and Forms

2. Bird’s-Eyes: Primulas

WOODEN MANIKINS: THE CULTS OF TREES

3. The Cult of Celebrity: The Fortingall Yew

4. The Rorschach Tree: Baobab

5. The Big Trees: Sequoias

6. Methuselahs: Bristlecones and Date Palms

7. Provenance and Extinction: Wood’s Cycad

8. From Workhorse to Green Man: The Oak

MYTHS OF CULTIVATION

9. The Celtic Bush: Hazel

10. The Vegetable Lamb: Cotton

11. Staff of Life: Maize

12. The Panacea: Ginseng

13. The Vegetable Mudfish: Samphire

THE SHOCK OF THE REAL: SCIENTISTS AND ROMANTICS

14. Life versus Entropy: Newton’s Apple

15. Intimations of Photosynthesis: Mint and Cucumber

16. The Challenge of Carnivorous Plants: The Tipitiwitchet

17. Wordsworth’s Daffodils

18. On Being Pollinated: Keats’s Forget-Me-Not

NEW LANDS, NEW VISIONS

19. Jewels of the Desert: Francis Masson’s Starfish and Birds of Paradise

20. Growing Together: The East India Company’s Fusion Art

21. Chiaroscuro: The Impressionists’ Olive Trees

22. Local Distinctiveness: Cornfield Tulips and Horizontal Flax

THE VICTORIAN PLANT THEATRE

23. ‘Vegetable jewellery’: The Fern Craze

24. ‘The Queen of Lilies’: Victoria amazonica

25. A Sarawakan Stinkbomb: The Titan Arum

26. Harlequins and Mimics: The Orchid Troupe

THE REAL LANGUAGE OF PLANTS

27. The Butterfly Effect: The Moonflower

28. The Canopy Cooperative: Air Plants and Bromeliads

29. Plant Intelligence: Mimosa

Epilogue: The Tree of After Life

Additional References and Sources

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction: The Vegetable Plot

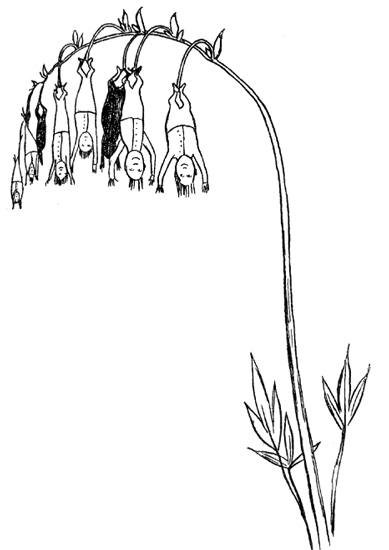

JUST BEFORE HE DIED in 1888 Edward Lear sketched the last of the surreal additions to evolution’s menagerie that he’d begun with the Bong-tree in ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’ nearly twenty years before. His Nonsense Botany is a series of impish cartoons of preposterous floral inventions. It includes a strawberry bush bearing puddings instead of fruit, the parrot-flowered Cockatooca superba and the unforgettable Manypeeplia upsidownia, a kind of Solomon’s seal with minute humans suspended like flowers along the bowed stalk. Lear was a lifelong sufferer from epilepsy and depressive episodes (which he nicknamed ‘the Morbids’ as if they were a tribe of gloomy rodents) and the obsessive fun he had with words and forms may have been a way of exorcising his melancholy. But I suspect there is more to his final creation. Lear was an astute botanist as well as a brilliant humorist. He’d travelled and painted across the Old World, especially in the Mediterranean, and had seen first hand many of its bizarre plants, including the carrion-stinking dragon arum (which he described as ‘brutal-filthy yet picturesque’), and I think his nonsense flora can be seen as a kind of celebratory cabaret, an affectionate satire on the astonishing revelations of nineteenth-century botany.

Manypeeplia upsidownia, from Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany.

Thirty years previously Europeans had their first news of the Welwitschia, a Namibian desert plant whose single pair of leaves can live for 2,000 years, grow to immense size but remain in the permanently infantilised state of a seedling. Ten years later Charles Darwin had revealed the barely credible devices orchids used to conscript insect pollinators, including the launching of pollen-laden missiles. In a world of such remarkable organisms why shouldn’t there be a fly orchid dangling real flies like Lear’s Bluebottlia buzztilentia? As for his Sophtsluggia glutinosa, it could well be the filthy dragon arum reimagined as one of the plant–animal cooperatives being unmasked by explorers in the tropics. Lear’s bionic vegetables were botany’s reductio ad absurdum, the last tarantellas of a century in which plants had been just about the most interesting things on the planet. It wasn’t a fascination confined to the scientific elite. The general public had been agog, astounded by one botanical revelation after another. In America the discovery of the ancient sequoias of California in the 1850s drew tens of thousands of pilgrims, who saw in these giant veterans proof of their country’s manifest destiny as an unsullied Eden. (There were throngs of rubberneckers and partygoers too: nineteenth-century botany was far from sober-sided.) Similar numbers flocked to Kew Gardens in west London, where one of the star attractions was an Amazonian water lily whose leaves were so brilliantly engineered that their design became the model for the greatest glass building of the nineteenth century. What these moments of excited attention shared was not so much a simple pleasure in floral beauty or the promise of new sources of imperial revenue (though these were there too) but a sense of real wonder that units of non-conscious green tissue could have such strange existences and unquantifiable powers. Plants, defined by their immobility, had evolved extraordinary life-ways by way of compensation: the power to regenerate after most of their body had been eaten; the ability to have sex by proxy; the possession of more than twenty senses whose delicacy far exceeded any of our own. They made you think.

Yet if respect for them as complex and adventurous organisms reached its zenith in the late nineteenth century, it neither began nor ended there. People had been enthralled by and sometimes fearful of the vegetable world’s alternative solutions to living for thousands of years. They contrived myths to explain why trees could outlive civilisations; invented hybrid creatures – chimera – as models for plants they were unable to understand, and which seemed to intuit symbioses discovered centuries later. Ironically, the same scientific revolution that engaged the public imagination eventually alienated it. Alongside Darwin’s work, Gregor Mendel’s discoveries of the mechanisms of genetic inheritance in the late 1860s drove botany deeper in to the laboratory. The workings of plants became too difficult, too intricate for popular understanding. Amateur botanists turned instead to recording the distribution of wild species. The rest of us mostly sublimated our interest in the existence of plants into pleasure at their outward appearance, and the garden has become the principal theatre of vegetal appreciation. Plants in the twenty-first century have been largely reduced to the status of utilitarian and decorative objects. They don’t provoke the curiosity shown to, say, dolphins or birds of prey or tigers – the charismatic celebrities of television shows and conservation campaigns. We tend not to ask questions about how they behave, cope with life’s challenges, communicate both with each other and, metaphorically, with us. They have come to be seen as the furniture of the planet, necessary, useful, attractive, but ‘just there’, passively vegetating. They are certainly not regarded as ‘beings’ in the sense that animals are.

This book is a challenge to that view. It’s a story about plants as authors of their own lives and an argument that ignoring their vitality impoverishes our imaginations and our well-being. It begins with the very first representations of plants in cave art 35,000 years ago, and the revelation that Palaeolithic artists were more intrigued by plants as forms than food. And it ends in a kind of modern cave: the hollow shell of a famous fallen beech, and what this apparently dead relic says about the ability of plants, working as a community, to survive catastrophe. In between, I discuss how medieval clerics and indigenous shamans laid down formal explanations of why one wilding could evolve into a food crop and another into a poison; the debate between Romantic poets and Enlightenment scientists about the kind of vital forces that might lie behind vegetal powers, and whether they echoed the creativity of humans; and today, how the puzzles that so excited the nineteenth century – do plants have intentions? inventiveness? individuality? – are being explored by a new breed of unconventional and multidisciplinary thinkers.

It’s odd that we haven’t regained our ancient sense of wonder, especially now we understand how crucial the plant world is to our own survival. Perhaps that is partly the answer: we find it hard to accept that plants don’t need us in the way we need them. The UN has described the 300,000-plus species which make up the earth’s flora as ‘the economy’s primary producer … photosynthetic cells capture a proportion of the sun’s radiant energy and from that silent diurnal act comes everything we have: air to breathe, water to drink, food to eat, fibres to wear, medicines to take, timber for shelter’. They are now a front-line crisis service too. Trees combat climate change, soak up floods, purify city air. Wild flowers help insects survive so they can pollinate human crops. The structures of plant tissues are providing models for a new generation of engineered, non-polluting materials. You would think that this increasing understanding of the centrality of plants’ role on earth might encourage a new respect for them as autonomous organisms. But the opposite is happening. Influential conservationists such as Tony Juniper have openly abandoned the idea of arguing for plants’ ‘intrinsic value’ in favour of stressing their economic potential, and have enthusiastically embraced the jargon of the marketplace. Wordsworth’s ‘host of golden daffodils’ has been rebranded as ‘natural capital’ and the Wildwood as a provider of ‘ecosystem services’. ‘Nature’, once seen as some kind of alternative or counter to the ugliness of corporate existence, is now being sucked into it. I’ve no doubt that the pragmatic realpolitik and self-interest of this approach are powerful motivators for conservation. But I think of George Orwell’s words: ‘if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought’. And worry about the subliminal effects of defining plants as a biological proletariat, working solely for the benefit of our species, without granting them any a priori importance. One doesn’t have to believe that plants have rights to see that this is a precarious status, subject to the swings of human taste and attitude. In the absence of respect and real curiosity, attentiveness falters. Complex systems become reduced to green blurs, with dangerous consequences both for us and for individual species. An example of well-meaning but myopic human-centred thinking is the encouragement being given to the growing of nectar-rich flowers for pollinators, bees especially. This is a commendable policy – except that the majority of pollinating insects, unlike bees, grow from larvae that feed not on nectarous flowers but dull green leaves, some of them the weeds that are hoicked out to make way for the dazzling floral border.

I suspect that the chief problem we have in considering plants as autonomous beings – and let me risk embarrassment by using the word selves here, meaning authors of their own life stories – is that they seem to have no animating spirit. I was lucky in that I had an early and revelatory glimpse of their vitality. I tell the full story later of how one species, marsh samphire, took me through this transformative experience, but its outlines are relevant here. I first came across the plant as a commodity, a foodstuff, a very desirable wild delicacy (I still rate it foraging’s gold star species), and then discovered that it had an enthralling existence beyond my use for it – a love for bare, viscous mudflats which was seemingly contradicted by an inherent drive to turn them into dry land.

Most of my personal encounters with plants – some of which are described in the pages that follow – have confirmed this conviction that plants have agendas of their own. On every occasion I have owned, or had control of, or planned purposes for vegetation, what has enthralled me has been the way the plants go off on courses entirely of their own. During the years I owned the deeds of an ancient wood in the Chilterns (I can’t say I truly owned the living place itself) our feeble attempts at tree planting were swamped by the wood’s decision to grow quite different species. Supposedly shy and finicky plants – rare ferns, native daphnes, the only colony of wood vetch in the county of Hertfordshire – ramped along tracks we’d gouged out with a bulldozer. Violet orchids grew in thickets where it was too dark to read – then vanished when the light broke in.

Everywhere I have travelled plants have surprised me by their dogged loyalty to place, even to the point of defining the genius loci, and then by their capricious abandonment of home comforts to become vagrants, opportunists, libertines. I’ve seen ancient goblin trees develop wandering branches as promiscuous as bindweed shoots, which might equally well lope off into the countryside or jam themselves into a city wall. I’ve marvelled at tropical orchids living off air and mist. Plants, looked at like this, raise big questions about life’s constraints and opportunities – the boundaries of the individual, the nature of ageing, the significance of scale, the purpose of beauty – that seem to illuminate the processes and paradoxes of our own lives.

And this, of course, is where the problems arise. Is it possible to think and talk sympathetically about a kingdom so different from our own without in some way appropriating and traducing it? Do we inevitably impose linguistic bondage whenever we try to celebrate vegetal freedom? Is this book’s project a contradiction in terms? Our traditional cultural approach has been dominated by analogy. For at least 2,000 years we’ve tried to make sense of the barely animate world of plants by comparing its citizens to models of liveliness we understand – muscles, imps, electric machines and imperfect versions of ourselves. Daffodils become dancers and ancient trees old men. The folding or falling of leaves is a kind of sleep, or death. We’re Shakespeare’s forked radishes attempting to solve the monkey puzzle.

Metaphor and analogy are regarded as inappropriate, even disreputable, in scientific quarters. They’re liable to divert attention away from the real-life processes of plants, and to end in the ultimate heresy of the pathetic fallacy, of seeing plants as the carriers or mirrors of our emotions. But I can’t see how we can hope to find a place for ourselves in earth’s web of life without using the allusive power of our own language to explore plants’ dialects of form and pattern, and their endless chatter of scents and signals and electrochemical semaphore. In return the plant world has repaid us with a rich source of linguistic imagery. Root, branch, flowering, fruiting – we can think more clearly about our own lives because we have taken plants into the architecture of our imaginations. The trouble has been not so much with metaphor itself, as with a kind of literalism, where what is intended to be simply an insightful allusion becomes a humanoid tree or a pansy (from French pensées, thoughts) endowed with tender feelings. (An extreme example of this was the fashionable Victorian fad for ‘the Language of Flowers’, which ascribed plant species with a code of arbitrary ‘meanings’ which had no connection whatever with the lives of the organisms themselves.)

The great Romantic lover of plants, Samuel Coleridge, understood these tricky borderlines. ‘Everything has a life of its own,’ he wrote, ‘and … we are all one life.’ He was talking about the existence of the individual inside the community of nature, but he might also have been pondering how we set our measure of the world alongside, so to speak, the plant world’s measure of itself.

The diverse chapters that follow chiefly involve encounters between particular plants and particular people, and underline the point that respect for plants as autonomous beings doesn’t preclude our having a relationship with them. Indeed, one alternative to viewing ourselves as natural capitalists would be to begin thinking as natural cooperators. Or as the participating audience in an immense vegetable theatre in the round. In 1640 John Parkinson, apothecary to King James I, wrote a book entitled Theatrum Botanicum. The Theatre of Plantes, though its subtitle – An Universall and Compleat Herball – gives away the staid procession of second-hand plant remedies that follows. I wanted a frame which suggested the possibilities of a more intimate, interactive relationship between our two spheres of existence; a sense of the vegetal world as protean, dissident and Learish, full of mimicry and unexpected punchlines, and a long way from abiding by anyone’s stage directions. A cabaret sounded like the right kind of show.

Some of the chapters (or acts, maybe) are portraits of individual organisms – the Fortingall yew, for example, probably the oldest tree in Europe and a hapless arboreal celebrity; Newton’s apple tree, whose genetic and ecological history lays waste to the gloom of Newton’s physics. Other chapters are meditations on whole groups of plants – oaks, orchids, carnivorous species – whose rich cultural histories braid with their own ecological narratives. There are chapters on writers and artists – Wordsworth on daffodils, Renoir on olives, photographer Tony Evans on primulas – whose vision changed our understanding of the vitality of plants and how we might relate to it. There are accounts of some personal explorations of the Burren in Ireland and the gorges of Crete, and what their flora says about the dynamics of vegetation, in the past and in the future. And there are introductory sections on ideas, for instance Romanticism, the role of glass in plant theatre, and the vexing question of plant intelligence.

This all sounds very serious. Plants are also fun and feisty, and I hope this book celebrates that, as well as their gift to us of different models of being alive.

HOW TO SEE A PLANT

THE SACRED LOTUS, with its bounteous white flowers and pristine leaves levitating above even polluted Asiatic rivers, is one of the most beautiful and revered plants on earth. Across 2,000 years and a swathe of cultures, it has been a symbol of purity rising out of corruption. Right up until the Maoist Revolution Chinese children were expected to memorise a lotus homily written by the eleventh-century philosopher Zhou Dunyi:

[The lotus] emerges from muddy water but is not contaminated; it reposes modestly above the clear water; hollow inside and straight outside, its stems do not struggle or branch … Resting there with its radiant purity, the lotus is something to be appreciated from a distance, not profaned by intimate approach.

Vegetal hygiene becomes visual beauty becomes a respectful ethical principle. Did early Chinese scientists understand how lotus leaves were able to throw off the mud they grew through, and be seen, emblematically, as a kind of moral Teflon? It’s now known that the peculiar surface characteristics of the leaves make it impossible for fluids, however viscous and contaminated, to get a grip, and they simply flow away. The leaves self-clean. Today, while garlands of the starry flowers continue to be worn as Buddhist religious symbols, the engineering of the leaves has been appropriated by secular technology to manufacture a range of products patented under the trademark ‘Lotus-Effect’. They include a house paint that is claimed never to need washing, except by rain, and non-stick spoons for honey. When we look at a sacred lotus, do we intuit this fundamental part of its identity, the root source of its symbolic power as well as its survival as a plant? Or just see the gentle welcome in the gorgeous petals?

While writing this chapter I persuaded the curator at Kew Gardens to let me take some lotus leaves home. They made a rather nondescript bundle, like a sheaf of rhubarb. But I had a plan for them. My partner Polly’s grandkids – aged nine, seven and four – were staying for the weekend, and I wanted to know how they ‘saw’ the lotus, and what they made of its remarkable behaviour in contact with fluids, especially gooey ones. They enjoyed the strange velvet feel of the leaves, at least to start with. But children aren’t aesthetes in that sense. They wanted action. I tried plain water first, holding a leaf horizontally so that it formed a shallow bowl, pouring in a cup of water, then gently tilting it back and forth. Globules of silver water whizzed about the leaf, occasionally coalescing, then being broken up into grapeshot by the ribs. The children burst into hysterical giggles, a sure sign of amazement. I can’t believe the youngest had ever seen mercury, but he remarked, with precocious poetry, that the water roller-balls were like ‘liquid metal’. Dirty water was next, and produced the same results, but nothing compared to the theatrical effect of tomato ketchup, which wriggled about the leaf like a company of disorderly scarlet slugs. Then I just tipped the whole lot off and flourished a completely unstained leaf.

Later I showed them an electron micrograph of the leaf’s surface, and the rows of close-stacked, smoothly rounded pimples which are the reason even the stickiest fluids can’t get a grip. But they were only marginally interested. This was not what they had seen, had experienced. I left them with the remaining leaves and their yelps at the behaviour of egg and golden syrup, until stimulation fatigue set in and the leaves became more interesting as sun shades and face slappers.

Seeing a plant is a matter of scale and relevance. We notice aspects which accord with our own frameworks of time and proportion, and which speak to our needs, whether aesthetic or economic. Only rarely – when we’re children, for example, untroubled by such refined and narrow neediness – do we sometimes glimpse what is important for the plant itself. In this section I have looked at how the first modern humans, the Palaeolithics, saw plants; and how, working with an insightful photographer, I began myself to learn how the superficial appearance of a plant – our framed image of it – relates to its own life and goals.

1

Symbols from the Ice: Plants as Food and Forms

THE COMPELLING IMAGES OF NATURE in the caves of southern Europe are our species’ earliest surviving works of imaginative representation. The galloping horses and rippling bison created by Palaeolithic artists up to 40,000 years ago are very evidently themselves, but also seem to stand for elusive abstract notions: symbolic forms, the energy of movement and creation, perhaps a world beyond the physical. What is curious, given the way that plant representations were to proliferate in future millennia, is how sparse images of the vegetable world are, and how vague. Most of the creatures painted on cave walls or engraved on bones are instantly recognisable as animals. There are a handful of images, too, that have a vaguely branching plant-like quality. But I have only seen one image that is a convincing picture of a specific, potentially identifiable flower. On a bone found in Fontarnaud Cave in the Gironde and dating from about 15,000 BC, a twig bearing four bell-like blooms rises up like a miniature maypole in front of a reindeer antler. The flowers are lantern like, pinched and cut into a V at the lip, with their stalks projecting alternately up the stem. It’s a passable impression of a sprig of bilberry, or crowberry, or one of their ericaceous relatives that grew abundantly on the late ice age tundra. Foliage and fruit were food for the reindeer, which, in turn, were food for the local hunter-gatherers. If this is a deliberate juxtaposition, it’s a clever and symmetrical one – prey animal and prey’s forage – except for one complicating feature. When I looked at a close-up photograph of the carving, I spotted something I hadn’t seen before. Near the point at which the each bloom grades into the stalk there is a small curved line, like a breve or a closed eyelid. When I focused on it, the ‘flowers’ suddenly flipped, like the shapes in M. C. Escher’s optical illusions. They became birds’ heads and necks, or maybe a notional impression of young, suckling animals. The flower as feeder as well as food. Had the artist made a kind of visual pun, or a metaphorical image about the circularity of the food chain?

Deer’s head and bilberry (?) carved on a bone from a cave in the Gironde, c. 15,000 BC.

Palaeolithic artists used metaphors freely. Dark pubic triangles represented women, and probably the idea of creation. Carvers used the natural curves in cave walls to highlight the rounded bellies of animals – rock paunches hinting at fodder consumed, or calves to come – and to give them the illusion of movement in flickering light. This stands for that. The long habit of seeing resemblances and analogies has been a defining feature of our species since the dawning of the modern mind in the caves, 40,000 years ago. I can’t help looking for metaphors in ice age art, any more than its creators could resist inserting them. So I may be translating this conjunction quite wrongly. Perhaps it is just the result of one artist filling in the bare space on another carver’s bone. Perhaps it is another kind of metaphor altogether, an image of sleep maybe, or not a metaphor at all but a sophisticated doodle, unconnected to the world’s greenery.

But Palaeolithic cave artists seemed chiefly to find vegetation visually unstimulating or short on meaning, despite the ubiquity of plants in their lives and landscapes. In the painted subterranean galleries of southern Europe you can only see plant forms by wishful thinking, conjuring up, say, a schematic tree from a few random scratch marks and ochre smudges. Cave art is overwhelmingly devoted to animals, but their habitat is invisible. Lascaux’s bison walk on air. The wild Tarpan ponies in the extraordinary, 35,000-year-old ‘Horse Panel’ in Chauvet Cave flare nostrils, pout and whinny, but never graze. There are plenty of food animals – deer, bison, mammoths – but no food plants. There are also fish and foxes, cave bears, predatory big cats, whales and seals, a tiny grasshopper, and three splendid owls from Trois Frères (Ariège), whose expressions have the same inscrutable wisdom conventionally given to owls in modern times. The flair with which these creatures’ vitality and shifting moods are captured makes it plain what caught the artists’ attention, and you wonder why their own kind didn’t inspire the same empathy. There are a few female figures engraved in caves and on artefacts, but they are mostly orotund symbols of pregnancy, tropes of pure fertility, and they lack the faces and individuality of the animal portraits. Plants don’t seem to belong to the same cosmos.

Yet they were indispensable parts of Palaeolithic life. Hunter-gatherers were just that, gatherers as well as hunters. They foraged for berries and roots. They would have understood how the migration of their food animals was governed by the growth spurts of tundra vegetation. They worked expertly in wood, once trees had begun to return to the landscape in the wake of the retreating ice. Remains of wooden bowls, tools, shelters, even cave-painter’s ladders, have been found in sites dating from the end of the Palaeolithic, circa 12,000 BC. The foragers may even have been making happenstance experiments in cultivation. Evidence of cereals, such as oats and barley, has been found in sites in Greece and Egypt. Concentrated clusters of grass pollen grains have been excavated in Lascaux, suggesting hay was gathered by the armful, perhaps for bedding. The evocative scent of drying grass may have drifted through the dreams of early artists, but not through their work.

Utility rarely seems to have been an overriding consideration in these first artists’ choices of subject. Non-food animals are pictured just as frequently as prey species, and the animals featured on the cave walls are rarely those whose stripped bones, the remains of dinner, are found on the floor. As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss has famously suggested, the painters’ subjects were not so much good to eat as ‘good to think’. Perhaps this is one reason why plants so rarely feature. They can’t be ‘thought’ in the same way as sentient creatures. They have no obvious animus or spirit. Their life cycles don’t follow the comprehensible pattern of pregnancy, birth and death which all animals share. In the big bisons in Chauvet Cave – drawn with a few simple strokes that give them the bulk and energy of Picasso’s bulls – you are seeing a creature whose power and thunder and fecundity have been felt in the bone by the artist. It is hard to imagine any clump of green tissue, however culturally significant, nourishing such fellow feeling.

My friend, biologist and painter Tony Hopkins, spent twenty years sketching rock art round the world. This is no longer regarded as a reliable recording technique, given the seductive opportunities it allows for fanciful interpretation. But the process of creating impressions of the images, forming reproductions of the pictures his fellow artists made tens of thousands of years ago, has given him a privileged insight into what might have been in their minds. Beyond a few comparatively recent Australian Aboriginal paintings of gourds and yams, Tony has seen no truly ancient representations of plants. His own interpretation of this, he tells me, is ‘that most cultures saw plants as being part of the landscape, the same as mountains and rivers. This does not mean that they didn’t think they had “spirits”. But plants were not part of the palette of iconography. I think this might be because people could not see themselves in the plants, but could see themselves (or could see their shamans) transmuted into animals. Perhaps this implies that people did not think plants were “alive”.’ Or perhaps took them for granted, as predictable ‘givens’, like their habitat, or cloud formations, or their own bodies, also rarely represented in their art. Yet the absence of plants from rock art doesn’t necessarily mean they were absent from the imaginative world of the Palaeolithic. They may have had meanings that were not easily accessible to representation, in the manner of scents which can be described only by similes or by reference to other scents.

Theories about the ‘meaning’ or, even more riskily, the ‘purpose’ of cave art have flourished since the first examples were uncovered in the late nineteenth century, and tend to echo the contemporary zeitgeist. The Victorians, smarting at the way this sophisticated art undermined the presumptions of civilisation, dismissed it as a collection of doodles, or the work of unconsciously gifted copyists. In the early part of the twentieth century, ethnographers with colonial models of ‘primitive’ cultures put the pictures down as hunting cartoons, narratives of the chase, field guides to the most desirable quarry. Or perhaps as magical aids to hunting, an envisioning and therefore ‘capturing’ (a word we still use about pictorial likenesses) of prey. In the psychedelic mood of the 1960s and 70s, there were theories which linked the images to altered states of consciousness and shamanic drug-driven rituals. Spears were spotted everywhere, as were genitalia (particularly dark pubic triangles, the pan-global symbol of generative power) and the pictures were interpreted in some quarters as Palaeolithic pornography, celebrations of sex and violence. In the late twentieth century French structuralists concentrated their attention on the overall arrangement of the pictures inside caves. Bison confronting horse, for example, has been interpreted as a masculine–feminine opposition, and a clue to the structure of Palaeolithic belief systems. The location of paintings in very remote parts of the caves may suggest that they were positioned close to a metaphorical portal to the animals’ spirit world.

Nowadays most archaeologists are wary of grandiose, overarching theories about the meaning of cave art. Indeed, simply to ask what they ‘mean’, as if there were a solitary purpose and a single artistic ‘language’ in the Palaeolithic, smacks of a kind of patronisation, a reluctance to credit people who are manifestly already using their imaginations expressively with the same rich muddle of beliefs and feelings that have always lain behind creative art. We will never know for certain why ice age people made images, or chose the subjects they did. Jill Cook, senior curator in prehistory at the British Museum, put the dilemmas (and some of the wilder theories) of interpretation in perspective when she described an exquisite sculpture of a water bird found in a cave in southern Germany. It is only two inches long, but perfectly streamlined, as if caught in the act of diving. It may, she says, be a ‘spiritual symbol connecting the upper, middle and lower worlds of the cosmos … Alternatively it may be an image of a small meal and a bag of useful feathers.’

From the simple act of looking at the pictures, one thing is indisputable: their creators were artists, in exactly the sense we understand today. Their work vivaciously displays all the emotions associated with the acts of image making and image viewing: wonder, love, fear, amusement, a celebration of life, a satisfaction in the business of creation. The first reaction of most lay viewers of Palaeolithic art isn’t one of anthropological interrogation but of recognition, plus a delighted astonishment that these remote ancestors saw and created in ways that are so comprehensible to us. Art was born 40,000 years ago, in John Berger’s phrase ‘like a foal that can walk straight away’. This isn’t a matter of imposing modern sensibilities on ‘primitive’ intelligences. The Palaeolithic mind was the modern mind in embryo. That defining movement towards self-awareness, when the mind shifted, became conscious of itself and of the fact of consciousness; and an image in the memory, the mind’s eye, meshed with the shadows on the rock, was also an aesthetic event. It meant that nature could be seen detached from itself, across space and time, and that choices could be made about how it was represented and seen.

In 2013 Jill Cook curated Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind – a spellbinding exhibition in the British Museum of what is called ‘portative’ art, in contrast to ‘parietal’ or cave-wall art. The Palaeolithics scratched images on ox shoulder blades and mammoth tusks and interesting pebbles. They engraved deer on deer antlers, used the curves in animal bones to suggest perspective. Just occasionally they scraped out plant-like forms – a twiggy fork, a suspicion of a leaf. Some of these portable pieces might have been magical, carried to bring good luck on the hunt. A few have been found with the bones of their owners, as if they were tributes or grave goods. But the majority seem more light hearted, with the look of art made for whimsy or pleasure, and may have been the work of different community members, less specialist workers than the ones who fashioned the set pieces inside the caves. Palaeolithic bone whittlers made toys, trinkets, tiny vignettes. One engraved a whale with a look of sublime serenity on a fragment of whale ivory. Another, about 15,000 years ago, cut a small figure of a ptarmigan into a bleached reindeer antler, a white bird in a snowbound and plantless void. In France, at about the same time, a hunter with a sense of vision and plenty of time to spare made what was essentially the first animation projector. It is a small bone roundel laboriously shaved down to just 0.1 inches in thickness, a monumental task. On one side is an engraving of an auroch’s cow, on the other her calf, whose outline beautifully catches the sagginess of young bovines. In the centre of the disc is a hole through which a thong was threaded, so that the disc can be twirled and the mother and calf made to perform a dance of transformation. It is a kind of Stone Age flick book, an ancestor of nineteenth-century moving-image machines. Most extraordinary is the oldest wind instrument in the world, a 35,000-year-old flute cut from the wing bone of a griffon vulture. Experiments with replicas show that the way the holes are positioned make them exactly reproduce the top notes in the modern diatonic scale.

Jill Cook mounted these pieces in small glass booths, so that as you gazed at them you saw the reactions of the viewers opposite you: engrossment, recognition, tears; many complex expressions of loss and rediscovery. The poet Kathleen Jamie was there, and wrote about this shared sense of time dissolving: ‘Perhaps because we were Palaeolithic for such an age, the artworks we see before us are deeply, if strangely, familiar. We peer and half remember.’ Kathleen and I agreed afterwards that we felt something strangely akin to homesickness in front of these extraordinary miniatures made by our ancestors, and that gathering together in a circle round these enclosed images touched some deep memory of those evenings round the cave fires.

Yet there were no plant portraits in the exhibition, despite the fact that it is on portable pieces that most of the meagre collection of early images appear. When Paul Bahn and Joyce Tyldesley reviewed all images in the European Palaeolithic era that might possibly represent or reference plants they found just sixty-eight, and of these fifty-eight were portative. Compared to the dazzling artistry of the animal portraits (probably created by an elite class of full-time painters and engravers), the exterior images are naive. Half a dozen or so are crudely naturalistic. On a baton carved from reindeer antler there are three stalks of an aquatic plant, possibly a water milfoil. A pebble from the Grottes de Cougnac near Gourdon is engraved with what is clearly a monocotyledon (the large section of plants that includes grasses and lilies). The finders suggest it might be a tulip, but the little cluster of pearl shapes above the thickly sheathed leaves look to me more like an orchid, or a lily of the valley in bud. The most gracious – and accurate – is a spray of what is almost certainly a willow, carved on a reindeer shoulder blade. The leaves are alternate, and there is a side twig that tracks the swelling at the head of the bone, a classic Palaeolithic trope. There is even a stick-beast impression from the Ariège of what is probably a deer or cow browsing low foliage, but mystifyingly interpreted by the French structural anthropologist Alexander Marshack as ‘a man in the midst of stylised reeds or rushes’. And then there is the puzzle of the bilberry-reindeer collage.

Most of the rest are little more than variations on simple leaf or twig forms. Branching patterns appear often, as radiating ribs in a leaf, or a series of forks. Structuralist interpreters are reluctant to take these images at face value. The simple fork, the basic binary division, the turning of one into two, is a universal pattern in nature, as it is in the structure of thought. The bifurcating twigs may be fertility symbols, or then again feathers, or fins. All have been the subject of intense study by Marshack or his colleagues. Arl Leroi-Gourhan translates a simple engraving of a small twiggy plant with roots as a female oval symbol supporting a branching male symbol. Inverted V shapes on a carved rib from the Dordogne are interpreted as either tree buttresses or symbols of female ‘entry points’ (they may be both – splayed and buttressed roots are commonly seen as vaginal symbols by surviving hunter-gatherer communities in Amazonia) and the monkish hominids walking past them as men carrying sticks on their shoulders. According to who is interpreting the drawings, stick images may represent harpoons, ‘male elements’, or just plain sticks. Here and there on other bones and pebbles are clusters of small cruciform or star shapes. Marianne Delcourt-Vlaeminck interprets these as schematic flowers, but they may be stars, or sparks, or those optical flashes known as phosphenes that are often experienced in the dark, and especially during moments of awareness heightened by dance or drugs.

Much of the structuralist deciphering of this slender collection of plant images seems to me as fanciful as glimpsing pictures in the embers of a fire. Sixty-eight roughly scratched images, a minute fraction of what must have been created over a time span of more than 10,000 years, are not remotely sufficient evidence to tease out a lexicon of Palaeolithic foliate symbols. In the absence of any solid proof either way, I’d like to suggest a more inclusive and equally plausible account of their origins, which for me makes these early moderns feel more like the ancestors they were. The rank-and-file hunter-gatherers have a little time on their hands, maybe after a meal. They have a superfluity of stripped bones and flint burins, and are becoming familiar with the idea of making pictures from the work of the ‘professional’ artists inside the caves. The Palaeolithic evening class chip and scratch, some maybe working in pairs or groups, some producing little more than scribbles, like the marks young children make when they first have access to pencil and paper. The more accomplished are attempting to capture the intriguing forms that make up the green backcloth to their lives, maybe adding ciphers and clan emblems and entirely personal curlicues. The plant as a spontaneous cultural motif, rich with everyday metaphorical meaning, has its first tentative beginnings here. I’m reluctant to call it ‘decorative’, because of the etymologically unwarranted associations of superficiality which flutter around this idea. What I’m suggesting is that plant images and metaphors were used very freely, and continue to be so in the visual vernacular, as if floral and foliate growth somehow echo the dynamic processes of our imaginations. If animals have chiefly been metaphors and similes for our physical behaviour, plants – rooting, sprouting, forking, branching, twining, spiralling, leafing, flowering, bearing fruit – have, from these hesitant beginnings in the Palaeolithic salons, come to be the most natural, effortless representations of our patterns of thought.

But the physical evidence of these beginnings is slim, and if the paucity of images rather than their style is really the important part of the story, there may be an alternative interpretation. Not yet part of early culture and belief systems, kept outside the dark theatres where the human imagination took flight, undomesticated and unrevered, plants were still essentially wild. It was a quality and a status that was soon to be eroded by the invention of agriculture. What had been ‘outside’, beyond, was now ‘taken in’, enclosed. What had followed its own twiggy path was now drilled into our straight furrows. If you consider the whole tradition of images and conceptual framings of plants, it is striking how often they occur in spaces that have a sense of enclosure and possession. Depiction of plants doesn’t start again till 5,000 years after the end of the Palaeolithic era, and the simultaneous beginnings of agriculture in the Middle East. In Egyptian art, already well populated with birds and animals, notional plants begin to appear about 2500 BC. A thousand or so years later the pictures are beginning to be impressively accurate, and often embedded in some kind of narrative of enclosure. On one of the walls of Sennedjem’s tomb in Thebes there is a painting of a fully working farm. The estate is surrounded by irrigation channels and divided up into tidy fields. In one, a man (possibly Sennedjem himself) and his wife are picking bushels of flax. In an adjoining plot he is harvesting what look like ripe barley heads with a sickle. It is a naturalistic portrait of humans in full command of the plant world but, positioned as it is in a nobleman’s tomb, is probably allegorical, too – the farm already, as it would continue to be, a symbol of human life on earth, with all its stations of fruiting, harvest, death and rebirth.

At much the same time, in nearby Mesopotamia, the Genesis myth of an enclosed garden began to take shape, a model which was echoed three millennia on in the hortus conclusus of the Middle Ages. The first botanic gardens, created in the seventeenth century, were attempts to reconstruct the lost order of the Primal Plot: Eden itself. When they later became centres for the advancement of science and commerce, the sense that they were also botanical theatres for staging the unfolding dramas of theology and science was unmistakable. Soon botanical wonders from across the globe were being displayed on literal stages, in the bijou bell jars of Victorian drawing rooms and the great glasshouses of country houses and public gardens. Contemporary descriptions of the multitudes who came to stare at them hint that they resembled excited theatre audiences, and sometimes supplicants in a temple.

In his famous ‘Allegory of the Cave’ from the Republic, Plato tries to express the nature of the everyday experience of the physical world by imagining a group of people chained inside a cave, facing a blank wall. They watch the play of shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of a fire located behind them, and begin to give names to the shapes and to discuss their qualities. The shadows – visual metaphors, so to speak – are as close as the prisoners get to viewing the real world. Plato then explains (rather self-servingly nominating the philosopher as the one character qualified to find a way out) that only by leaving the cave can people experience the true nature of reality.

The beginnings of horticultural order. Garden of fruit trees enclosing a flower-bordered duck pond, Tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, c. 1350 BC.

Our perception and understanding of plants has, shall I say, been less black and white and more diversely democratic than Plato’s allegory. But the counterpoint between ‘real’ plants and the shadowy forms of metaphor, and between the spontaneous, imaginative experience of vegetation and the models of scientific, commercial and priestly elites, are themes which meander through this book.