Hot Spots in Global Politics

Christoph Bluth, Korea

Alan Dowty, Israel/Palestine 3rd edition

Kidane Mengisteab, The Horn of Africa

Amalendu Misra, Afghanistan

Gareth Stansfield, Iraq

Jonathan Tonge, Northern Ireland

Thomas Turner, Congo

Copyright © Samer N. Abboud, 2016

The right of Samer N. Abboud to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2016 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-9797-0

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-9798-7(pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abboud, Samer Nassif.

Syria / Samer N. Abboud.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-7456-9797-0 (hardback) – ISBN 978-0-7456-9798-7 (paperback) 1. Syria–History–Civil War, 2011- 2. Syria–History–Civil War, 2011—Refugees. 3. Syria–Politics and government–2000- I. Title.

DS98.6.A233 2015

956.9104′2–dc23

2015018380

Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Sabon

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in The United Stated by Courier Digital Solutions, North Chelmsford

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

To the memory of Obaida al-Habbal, and all of Syria's martyrs

When I was twelve years old my parents took us on a family trip to Lebanon and Syria, my first time out of Canada. While only three days of that summer were spent in Damascus, they were among the most memorable days of my young life and stayed with me for the next few years. I was so captivated by the city—its sounds, smells, and aesthetics—that more than a decade later I would return, this time as a doctoral student conducting research into the rapid economic change occurring in the country after the assumption of power by Bashar al-Assad.

When I first arrived in Syria as a researcher I was greeted by someone at the Baramkeh car park in Damascus with the kindest words: “Welcome to Syria, this country is for everyone.” For years, his welcome stuck with me and endeared me to the country and its people, if not the repressive regime that ruled over them. Over the last four years of the conflict I have spent many nights thinking about this man and the acquaintances, mothers, fathers, children, shopkeepers, taxi drivers, and servers I encountered over the years, and how the uprising has changed their lives. In some cases, I am fortunate to have my questions answered, but for the most part I am left only to speculate and fear the worst.

It is with a tremendous amount of sadness that I have written this book, which for me has been akin to recalling and retelling a tragic story that has played out for days, weeks, months, and years right before my eyes. As I, and so many others, have wandered helplessly trying to make sense of the Syrian tragedy, much of the world has watched with ambivalence befitting a weather report. I am certain that much of this stems from genuine confusion concerning the Syrian conflict and the ways in which it has been understood and analyzed in the West. Rather than delving into the complexities of the conflict, major media outlets, instant commentators, and the established pundits have preferred to frame the conflict in very convenient terms—regime versus rebels, good guys and bad guys, Alawi versus Sunni—then to offer sound analysis that contributes to understanding the main features, drivers, and dynamics of this extremely complex conflict.

In the pages that follow I attempt to provide a more complicated introduction to the Syrian crisis. This text does not present the conflict in rigid, dichotomous, and linear terms but aims to introduce you, the reader, to the different phases of the conflict and how it has evolved over the last four years. This book was written in relative solitude, but I am deeply indebted to a number of friends and colleagues who have provided me support over the years. First and foremost are Obaida al-Habbal, to whom this book is dedicated, and Zaher al-Saghir. Both Obaida and Zaher spent many hours with me in Damascus eating, laughing, walking, and talking about politics and history. Some of my fondest memories are of us on top of Mount Qasyun complaining about the inflated price of tea and coffee. I would also like to thank the many Syrians who took time to talk with me and introduce me to their beautiful country. There are far too many of them to name here.

Thanks are also in order for Pascal Porcheron and Louise Knight at Polity for their patience, kindness, and stewardship of the manuscript from beginning to end. Their encouragement throughout the process genuinely helped propel me in my moments of foundering. My research assistant, Josephine Lippincott, was not only an excellent and capable researcher who contributed immensely to this book but a wonderful motivator as well. My colleagues at Arcadia, Jennifer Riggan, Warren Haffar, and Peter Siskind, have been excellent sounding boards for both ideas and complaints over the course of writing this book. Peter deserves special thanks for regularly reminding me that I was capable of synthesis. My deepest professional gratitude is extended to Miguel de Larrinaga, Can E. Mutlu, Marc Doucet, Mark B. Salter, and Benjamin J. Muller, whom I feel honored to call my friends and colleagues and who have provided me with many hours of laughter over the last few years. Our regular email exchanges about everything from the intelligent to the absurd sustain me in immeasurable ways. I would especially like to thank my trusted friend Benjamin for many things, including his professional mentorship, regular parenting advice, and for introducing me to Western boots.

I am deeply indebted to my parents, Rabab and Nassif, for not only raising me with unconditional love but for making sure that we never went a day in our house without talking about politics. Their care and selflessness have always made me feel safe in this world. My extended family in Syria and Lebanon have helped me in countless ways over the last decade while I traveled back and forth from the region and I am grateful for the loving relationships that I have with them despite the vast distance that separates us.

Finally, I would like to extend my deepest love and gratitude to my wife, Sonia, and our children Kalila and Nadim, who bring us so much happiness and joy. Kalila and Nadim spent many hours coloring, connecting dots, building structures, and drawing various animals while I worked my way through this book. Sonia's support has been invaluable and I have benefitted greatly from her insights and analytical sharpness that helped me craft many of the arguments in the book. Most of all, I appreciate her love and patience. I would not have been able to complete this book without either.

| AQI— | al-Qaeda in Iraq |

| CBDAR— | Canton Based Democratic Autonomy of Rojava |

| FSA— | Free Syrian Army |

| GCC— | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| IF— | Islamic Front |

| ILF— | Islamic Liberation Front |

| ISIS— | Islamic State of Iraq and as-Sham |

| JAN— | Jabhat an-Nusra |

| KDP— | Kurdish Democratic Party |

| KNC— | Kurdish National Council |

| KRG— | Kurdish Regional Government |

| LAS— | League of Arab States |

| LC— | Local Councils |

| LCC— | Local Coordination Committees |

| MB— | Muslim Brotherhood |

| MSM— | Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen |

| NATO— | North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NCB— | National Coordination Body for Democratic Change |

| NDF— | National Defence Force |

| NRC— | Norwegian Refugee Council |

| NSF— | National Salvation Front |

| PKK— | Kurdistan Workers Party |

| PPC— | People's Protection Committees |

| PYD— | Kurdish Democratic Union Party |

| SAA— | Syrian Arab Army |

| SAMS— | Syrian American Medical Society |

| SIG— | Syrian Interim Government |

| SHRC— | Syrian Human Rights Committee |

| SIF— | Syrian Islamic Front |

| SILF— | Syrian Islamic Liberation Front |

| SKC— | Supreme Kurdish Council |

| SNC— | Syrian National Council |

| UAR— | United Arab Republic |

| UNHCR— | United Nations High Commission on Refugees |

| UNSC— | United Nations Security Council |

| UNSCR— | United Nations Security Council Resolution |

| UOSSM— | The Union of Syrian Medical Relief Organizations |

| UOSSM— | Syrian Medical Relief Organizations |

| UOSSM— | Union of Syrian Medical Relief Organizations |

| YPG— | People's Defense Corps |

The daily lives of Syrians have changed dramatically since March 2011 when protests against the fifty-year rule of the Ba'ath Party began in the southern city of Dar'a. What began as a movement of sustained protest demanding regime change and political reforms has morphed into one of the most brutal and horrific conflicts in the post-World War II era. The conflict has become protracted, with the principal armed actors entrenched and a political and military stalemate consolidating. In the context of this stalemate, the humanitarian crisis wrought by the conflict is worsening: more than half of the total population killed, maimed, or displaced within only four years. The human tragedy of the Syrian conflict has no current end in sight. Sadly, and much to the detriment of Syrian society for generations to come, many local and regional actors seem content to fuel the horrors of the violence and do not invest in a meaningful process that could end the conflict. From the Syrian regime itself, which bears ultimate culpability and responsibility for the descent into maddening violence, to the various rebel groups, to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and Iran, there is seemingly no interest in ending the conflict.

Telling the story of the Syrian conflict is a complicated endeavor, especially in a context in which popular understandings of Syria reduce the conflict to simple binaries (Sunni/Shi'a or regime/rebel) that betray both the complexity of Syrian society and the conflict itself. In the pages that follow I attempt to confront these simplistic dichotomies and to introduce instead a broader picture of the Syrian conflict, one that moves back and forth between the meta-issues (such as regional rivalries, international involvement, and ideological and sectarian calculations) and the micro-issues (such as intrarebel cooperation and conflict, the humanitarian crisis, and the administrative fragmentation of the country) that are shaping and driving the military and political dynamics of the conflict and creating the current stalemate. In introducing the dynamics driving the conflict I also answer questions about who the main actors are, including the Islamic State of Iraq and as-Sham (ISIS), whose rapid and brutal rise in Syria and control of large swathes of Iraq and Syria have complicated the dynamics of the conflict as well as the possibilities of reaching a solution in the short term. One of my central goals is not only to trace the rise of groups like ISIS but to shed insight into the constantly shifting nature of alliances among rebel groups, the issues driving the political elements of the conflict, and the main actors (both local and international) who are playing key roles in the conflict. The goals for this book are to help the reader understand the broader dynamics driving the conflict, why it has persisted, who the main actors are, and why it has evolved in the way that it has.

In the popular understanding of the Syrian conflict it has morphed from a revolution into a civil war (see Hughes, 2014) but the conflict is not as linear as this suggests. There remains an active, robust, and committed movement of Syrians trying to rebuild their country, and to lead it free of the regime and the armed groups that now control it. At the same time, there is a slow fragmentation of the country and the retreat of armed groups into small areas under their territorial control, which has fueled civil violence that is worse in 2015 than it was in 2012. Thus the Syrian conflict is more than an uprising that morphed into a civil war; it is a conflict in which a revolutionary project to restructure society remains present.

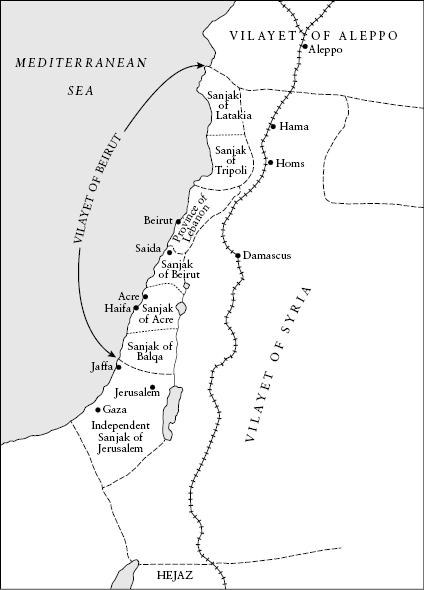

The Syrian conflict is not one with a definitive beginning or a linear trajectory. What is at stake, analytically speaking, is the understanding of the parallel processes of revolution and civil war and their short- and long-term effects on Syrian state and society. This requires an attentiveness to the nuances and complexities of the Syrian conflict that most popular understandings lack (Rawan and Imran, 2013). From my perspective, such attentiveness requires an examination of the interplay of many factors: historical analysis, political economy, the role of international actors, the structure of networks of violence, and so on. With this in mind, the story I tell in the pages below begins in the Ottoman era with the formation of a landed elite that controlled the political and economic levers of society right through to the Mandate period. In the post-Mandate period of independence, mobilization of the socially disaffected classes overthrew the notable order. Out of the remnants emerged the Ba'ath Party, which has ruled Syria since 1963. The subsequent decades witnessed the consolidation of Baathist control of Syria and state institutions and the emergence of an authoritarian regime that ruled Syria through a combination of repression and clientelism. The lack of any sort of political freedoms, and the massive socioeconomic changes wrought in the 2000s by a shift away from socialist-era policies toward the market, fueled societal grievances that eventually propelled the protests that began in March 2011. The Syrian state and society have undergone three seismic shifts in the last century: the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Mandate period, and the era of Ba'athist authoritarianism.

Intersecting with this historical evolution are the social realities consequent on changes in the nature and structure of the Syrian state. The expansion of the state under the Mandate authorities fundamentally changed the relationship between state and citizen and brought the political authorities into the everyday lives of Syrians. Under the Ba'ath, the state was reoriented toward the dual goals of regime preservation and social mobilization through state institutions that would link different segments of Syrian society, especially those on the peripheries of Mandate politics, to the state and regime. The incorporation of new social actors transformed the material and political basis of Syria's social stratification and brought to political power a regime that was dominated by leaders from Syria's minority communities and rural areas. Ba'athist rule involved the distribution of social welfare in exchange for political quietism in Syria's incorporated social forces. By the 1990s this model had exhausted itself, and the regime slowly turned toward the market. By the time the uprising began in 2011, Syria had undergone a decade of dramatic economic transformation that had ruptured the economic links between state and society established from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Syria played a major regional role during this period as well, having fought two wars with Israel in 1967 and 1973 and then intervening in Lebanon's civil war later in the 1970s. The Syrian presence in Lebanon lasted until 2005, when a series of protests led to the withdrawal of the Syrian troops and security personnel who had exercised control over the Lebanese political system after the end of the country's civil war in 1991. The Middle East Peace Process in the early 1990s never realized a return of the occupied Golan Heights from Israel and a cold peace prevailed between the two countries up until today. Syria's regional alliances shifted considerably in the decades prior to the uprising, with the regime supporting various Palestinian factions against one another, Kurdish separatist groups in Turkey, and the Islamic Republic of Iran in its eight-year war with neighboring Iraq.

The legacies of Syria's historical evolution as a state, the transformation of its social stratification and political economy, and the changing geopolitical situation in the Middle East have all contributed to shaping the conflict today. The conflict itself has injected its own complexities into the Syrian arena with the arrival of armed groups such as ISIS and the emergence of Syrian Kurdish parties as major actors in the war. The role of regional actors in fomenting violence and supporting regime and rebel forces has internationalized the conflict in ways that decenter local actors from decision-making and power on the ground. Violence, fragmentation, and displacement are radically reshaping Syrian society.

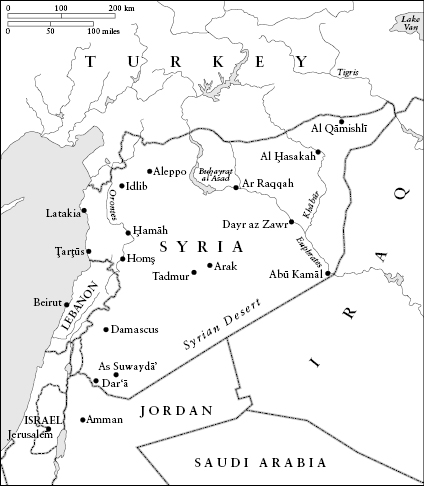

Syria is an extremely heterogeneous society, with Sunnis, Alawi, Ismailis, Druze, Shi'a, Greek Orthodox, Maronite, and other Christian sects. Population breakdowns by religion are not entirely accurate, but close to 10 percent of the population was Christian and the remaining 90 percent Muslim, the majority of which are Sunni Muslims. In addition to religion or sect, class, ethnicity, and geography are also determinants of Syrian political and social identity. Syria is dominated by Arabs with a sizable Kurdish minority, which is no more than 8 percent of the total population. Prior to the uprising, Syria's population was around 22 million, with more than half of the population formerly concentrated in urban centers.

Syria shares borders with Iraq, Palestine/Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey. The Golan Heights has been occupied by Israel since the 1967 war but is still home to many Syrian Druze who live under Israeli occupation. In the post-Mandate period, Syria's economy was dependent on agriculture and oil production. Agricultural production was central to the nation's social stratification in the Ba'ath period and oil revenues provided the regime with substantial rents to establish a strong central state and public sector. During the 1990s, there was a slow shift away from dependence on oil revenues and an attempt to diversify the economy. These reforms were accelerated in the 2000s when Syrian planners enacted policies to shift economic activity toward services. The shift in economic policy away from agriculture paralleled severe environmental degradation in the agricultural regions, including drought, which decreased agriculture's productivity and led to the transformation of the social basis around which agricultural activity occurred.

The complexity and fluidity of the Syrian conflict does not lend itself to any quick-fix theoretical models. Larger questions about why it has evolved in this particular way and why a stalemate has taken root are not easily answered. Much of the academic literature on wars and conflicts focuses on variables and measurements that do not remotely fit the realities of Syria's conflict. More nuanced studies have drawn on different approaches to the study of the Syrian conflict (Hokayem, 2013; Lesch, 2013a,b; Sahner, 2014). The background of the protests and the early mobilization period encouraged many to draw on Social Movement Theory (SMT) (Durac, 2015) to help understand the organization and strategies of the early protest movement that morphed into the Local Coordination Committees (LCC). This research, which we will deal with substantially below, has been important in helping us understand the main players fueling the protests, what their socioeconomic backgrounds were, how they organized and mobilized protesters, and what their key roles were in the early stages of the uprising.

Other studies of the conflict attempted to explain the causes and background of the uprising by focusing on the long trajectory and exhaustion of Ba'athist politics in Syria (Wieland, 2012). Further research has been conducted into the causes of the uprising, with some arguing that environmental factors such as climate change and drought were major drivers of the protests (De Châtel, 2014). Others point to Syria's socioeconomic situation on the eve of the uprising, especially the effects of unemployment and declining standards of living, as causes of the protests (Dahi and Munif, 2011) while others argue that the contagion effect of initially successful Arab uprisings in such places as Tunisia and Egypt inspired Syrians to protest (Kahf, 2014; Lynch et al., 2013).

While the study of the causes of the uprising are important, the uprising cannot be reduced to one or two variables. Instead, it is the outcome of the interplay of all of these factors. Some research has focused on explaining the trajectory of the uprising through changes in the regime's behavior and its subsequent mutations during the conflict (Heydemann, 2013a,b; Seeberg, 2014).

The regional geopolitical situation can explain some dynamics of the Syrian conflict, and further studies have focused on the interplay between domestic and regional politics by privileging the penetrative role of regional actors in Syria (Salloukh, 2013; Hokayem, 2013). Finally, others, such as Khashanah (2014), have argued that the confluence of ideological and geopolitical interests of outside entities induced the Syrian crisis in an attempt to realign the country's foreign relations.

All of these explanations have been substantial and useful interventions into the study of the Syrian conflict and all serve to inform much of the analysis that follows below. The multilayered complexity of the conflict necessarily produces intellectual and analytical blind spots and an exhaustive study of this complexity would be impossible given the rapidly changing dynamics of the conflict. In order to address these larger questions about the Syrian crisis, I have drawn on but sought to look beyond some of the dominant approaches to the study of the conflict. Rather than focusing exclusively or predominantly on the transformations of the regime or on the international role in the conflict, I have drawn significantly on the idea of wartime political orders to explain the key patterns of the conflict, including cooperation and conflict between different actors, governance, politics, military activity, war economies (Staniland, 2012), and so on. In drawing on this notion of a wartime order, I am trying to explicate some of the more nuanced questions that help parse the conflict: Why do rebels sometimes cooperate and sometimes engage in conflict? What do the political and administrative structures of nonregime areas look like? Who is exercising violence and to what end?

The study of wartime political orders typically relies on analysis of two variables: territorial control and regime-rebel relations (Staniland, 2012). Most literature on wars tends to ignore how the diverse and contradictory interactions between regimes and rebels serve to construct political authority and control. Regime and rebel actors are not locked in a zero-sum game to control the monopoly of violence; rather, they engage in both cooperative and conflict relationships that shape patterns of violence against civilians, governance, war economies, and, in important ways, postconflict politics. In this study of the Syrian conflict I highlight the diversity of interactions between regime and rebel groups, and also between rebel groups themselves. I look at how these groups control territory, administer that territory, and exercise political power and authority therein.

From the outset, then, it is important to clarify the meaning of “regime,” “rebel,” and “opposition,” which are often conflated. In the pages that follow, the homogeneity of these categories will be broken down in favor of more pluralistic and heterogenous explanations of what we call “the regime,” “rebels,” or “the opposition.” In Syria today, there are multiple actors that constitute the parts of what we mean when we refer to these categories. The analysis below highlights the fragmentation of these categories and what that fragmentation means for the conflict.

The Syrian conflict is not simply about military wins and losses or the contraction of regime territorial control. The conflict has produced a political order structured by relations among the different groups that produces patterns of violence and governance that are contributing to the stalemate. The relations produced by the conflict are themselves shaped by a number of factors, including the role of outside actors, sectarianism, territorial fragmentation, and the humanitarian crisis. In the pages that follow the story of the Syrian conflict is told through these lenses.

Chapter One begins with a historical overview of Syria's post-Mandate state up until the period of the Baathist coup in 1963. The chapter looks at the rise and consolidation of Baathist power from 1963 until the outbreak of the uprising in March 2011. In this period, the social and material basis of Ba'athist power shifted dramatically, especially in the period of Bashar al-Assad's rule (from 2000 onwards), during which the regime engaged in marketization that had accelerated the Ba'athist shift away from its traditional social support base. The role of the regime's pillars of power—the Ba'ath Party, the security apparatus, and the state—are discussed throughout. Specific attention is placed on the wide range of social forces in Syria—the peasants, urban bourgeois, workers, and so on—and their differential positioning vis-a-vis the entrenched time Ba'athist regime. This will provide a substantive background from which to understand the context of the uprising and the social forces driving the movement to topple the regime.

Chapter Two covers the first months of the uprising until the period in which militarization began to take root and an armed opposition emerged. Here we examine the background of the protesters and of the uprising and answer questions about how the protesters organized and mobilized in the context of sustained regime repression. The central role of the Local Coordination Committees (LCCs) is highlighted, as is how the conflict gave rise to civil activity and organization more generally. The regime's response to the protests was to engage in a dual policy of repression and reform, the latter of which included substantial constitutional changes but had no immediate effect on the ground. This did not placate protesters. Continued repression forced the uprising to emerge as a nonhierarchical, decentralized movement loosely linking activists together throughout the country. In addition to the LCCs, a political opposition made mostly of Syrian exiles formed outside of the country and attempted to generate international support for the overthrow of the regime. As armed groups emerged inside the country within the first year, the movement against the regime suffered from “multiple leaderships” and the lack of a centralized structure that could serve as a serious and legitimate alternative to the regime. The failure of the protests of the first months of the uprising to initiate regime change would propel the conflict toward increasing militarization.

The main violent actors are introduced in Chapter Three. In Syria today, violence is highly fragmented and decentralized, and there are two different armed actors: fighting units and brigades. The former are usually small armed groups with limited mobility who usually operate in smaller areas of towns or cities, while brigades have hundreds of members and are active across Syrian governorates. These units and brigades are connected to larger networks of violence that are determined by an interplay of many factors: resource access, control of checkpoints and supply routes, ideology, and so on. These networks of violence are very fluid and there remains mistrust between many of the armed factions. Chapter Three explores the networked structure of violence and how this manifests within the Jabhat an-Nusra, ISIS, Kurdish, and regime networks.

The international dimensions of the conflict are taken up in Chapter Four, which discusses the main positions and approaches to the conflict of the major international players—the Arab countries, Russia, Iran, Turkey, Hizbollah and Western countries. Key issues that contributed to the internationalization of the conflict include debates over intervention and arming the rebel groups, the chemical weapons containment issue, and rival peace processes sponsored by the United Nations and Russia. These are highlighted. This chapter identifies, then, both how international actors are penetrating the Syrian arena and affecting the evolution of the conflict and how the conflict has been internationalized.

Chapters Five and Six ask how the conflict is redefining Syria. Chapter Five concerns the territorial fragmentation of the country into areas loosely controlled by rival armed groups, including the regime, Kurdish Democratic Party (PYD), Jabhat an-Nusra and other Salafist-jihadists, and ISIS; it looks also at the latter three groups' administrative apparatuses, and. the failure of the exiled political opposition's attempt at a transitional government. Finally, Chapter Five considers some of the impacts of fragmentation, including the rise of sectarianism and the regional impacts of fragmentation on neighboring states. Chapter Six is concerned with the humanitarian crisis, specifically the displacement of millions of Syrians and the effect this is having on the health care and education access of Syrians. This discussion opens issues and challenges associated with refugee protection in neighboring countries. Chapter Six concludes with a discussion of the failings of the international community to adequately address the Syrian humanitarian crisis.