My Journey from Alaska to Israel

Ruth Gruber

To my young grandchildren

Michael and Lucy Evans

Joel and Lila Michaels

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Part 1: ALASKA

1 MISS GRUBER GOES TO WASHINGTON

2 FDR AND ELEANOR HOLD SEPARATE PRESS CONFERENCES

3 A CONTROVERSIAL BATH

4 SCHOOLMARMS AND WHORES

5 ANCHORAGE BOOMS

6 THE SILVER BULLET

7 SAILING DOWN THE YUKON RIVER

8 THE RIME OF THE BROOKLYN MARINER

9 NOME

10 LEARNING TO LIVE INSIDE OF TIME

11 THE MAD CRUISE OF THE ATALANTA

12 THE PRIBIL OF ISLANDS

13 ON MY WAY TO THE TOP OF THE WORLD

14 PREPARING FOR WAR

15 DECEMBER 7, 1941

Part 2: WASHINGTON IN WARTIME

16 THE WAR BECAME A MEMBER OF THE WEDDING

17 THE ARMY LAYS THE CANOL PIPELINE TO FUEL THE ALCAN HIGHWAY AND STRIKE AT JAPAN

18 HELEN ROGERS REID AND THE HERALD TRIBUNE FORUM

19 THE ROAD TO HAVEN

20 OSWEGO

21 WAR COMES TO THE WALDORF ASTORIA

22 THE END OF THE WAR

23 PANIC SPREADS

Part 3: THE DP CAMPS AND ISRAEL

24 OFF TO EUROPE

25 “WE WANT TO GO, WE MUST GO, WE WILL GO TO PALESTINE”

26 COLLECTING STORIES FROM DPS

27 NUREMBERG: TRIAL OF THE CENTURY

28 ARRESTED BY CZECH POLICE

29 A PRESS BLACKOUT IN VIENNA

30 FROM CAIRO TO JERUSALEM

31 “IF I FORGET THEE, O JERUSALEM”

32 WE VISIT THE KING

33 ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL?

34 “1947: THE FATEFUL YEAR”

35 THE LAST COMMITTEE

36 STORMING ACRE PRISON

37 EXODUS 1947

38 CYPRUS AND PORT DE BOUC

39 A LINE OF FIRE AND BLOOD

Part 4: THE BIRTH OF ISRAEL

40 THE NATION IS BORN, THE WAR BEGINS

41 LIFE AS A WAR CORRESPONDENT

42 BRUSHES WITH DEATH, BRUSHES WITH GREATNESS

43 FALLING IN LOVE IN PUERTO RICO

44 MR. BEVIN AND MRS. REID

45 THE WEDDING

46 ELEANOR VISITS THE HOLY LAND

APPENDIX

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

It was on my first trip to Alaska during World War II that I learned to live “inside of time.” I might be sitting in a place like Nome. I would send a radio message to Anchorage for a bush pilot to pick me up and fly me to Point Barrow.

The answer would come back, “See you Tuesday—WEAPERS.” “WEAPERS” meant weather permitting. Tuesday came. The next Tuesday came. Then the next. But no bush pilot. Usually it was the weather. Or the pilot was sick or on a binge.

Until that fateful voyage, I had been a restless fighter against time. If the elevated train from my shtetl in Williamsburg, Brooklyn to Manhattan was a few minutes late, I screamed at it under my breath like a longshoreman.

Now, instead of sending my blood pressure rocketing, I began to utilize the days and weeks of waiting. Wherever my lap was became my desk. I could fill more pages in my notebooks, send more reports to Harold L. Ickes, secretary of the interior—for whom I was working as field representative and later as special assistant—and interview more people, especially the Eskimos, whose serenity and affirmation of life I so admired.

Time was no longer my enemy. Now it enveloped me, liberated me. Living in a magical circle of space and energy helped fuel my love for words and images, the tools with which I would later fight injustice.

The patience and perseverance I learned stood me in good stead when Ickes, making me a simulated general, sent me to war-torn Europe in 1944 to shepherd one thousand refugees to safe haven in Oswego, New York. When we were blacked out, our engines silenced while Nazi planes flew over us and U-boats hunted us down, some of the wounded soldiers we carried shouted to me, “It’s these damn Jews—we survived all the battles, from Casablanca to Anzio, and we’re going to die because the Nazis know what we’re carrying.”

To show the soldiers what we were carrying, I arranged to have our gifted singers and actors perform for them. When the soldiers, their heads bandaged and their arms or legs in casts, watched and listened to some of our beautiful young women, they began to applaud with delight. It seemed to me they were seeing these artists not as objects of derision but as human beings.

Some talked to me of how amazed they were by the vitality and determination to survive of people who had suffered the greatest evil the world had known. The captain’s early order to me, “We don’t want any fraternization on this ship,” blew into the sea. The soldiers kept coming to our part of the ship bringing chocolate and cookies for our children and spending hours learning the life stories of some of the refugees. Anti-Semitism and hostility evaporated.

When the war ended, I traveled as a foreign correspondent through Europe and the Middle East with the Anglo-American Committee on Palestine. In Germany, we visited the terrible Displaced Persons camps taking testimony from the refugees. Some of the DP camps were former death camps and army camps in which these survivors of the Holocaust were now sleeping on the same wooden shelves where thousands had died during the war. I wanted to shake the world by its lapels: “Get rid of these camps. Open the doors of Palestine! After what they’ve suffered, let these Holocaust survivors go home.”

A year later, Helen Rogers Reid, the vice president of the New York Herald Tribune, sent me to cover UNSCOP—the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine. It was only the twentieth committee studying the problems of Palestine and the Arab-Jewish conflict.

We were listening to eloquent Jewish and Arab leaders in the YMCA in Jerusalem when I learned that a small American excursion boat named Exodus 1947, holding forty-five hundred Holocaust survivors, was being attacked by British destroyers and Ajax, the famous British cruiser. I rushed to Haifa and stood at the dock watching the battered ship enter the harbor. Three were dead: Bill Bernstein, the American second mate who had been bludgeoned to death, and two sixteen-year-old orphans.

The British officers made no effort to stop me from shooting pictures of soldiers dragging people off the ship and forcing them onto three ships sitting in the harbor. The commanding officer told me they were bound for Cyprus.

I flew to Cyprus to wait for them. It was a hellhole of sand and wind. No plumbing. No water. No privacy. I tried to capture it all in the articles and photos I kept sending the paper.

Cyprus became Helen Reid’s passion. Determined to use her influence with the British to get the Jews out of Cyprus, she used my articles as her weapon, but she failed. The British kept the Jews imprisoned on their island even after Israel was born.

David Ben-Gurion, the architect of the new nation, moved to Kibbutz Sde Boker in the Negev in the last years of his life. “If we do not conquer the desert,” he told me, “the desert will conquer us.” After his wife, Paula, died, he returned to his modest home in Tel Aviv, where I visited him shortly before his death in 1973. One of the soldiers stationed at the entrance told me, “It’s good you’ve come—so few people come to see him now.”

He was lying on the upper floor on a narrow bed, covered with a white quilt. On the floor below him were his sole companions, soldiers who guarded him, cooked for him, and occasionally ventured upstairs to make sure he was all right.

“Pull up a chair,” he spoke in a soft voice. I took a tape recorder out of my bag. He noticed it immediately.

“Put that thing away,” he demanded.

“B. G.,” I protested, “I want to have a record of your voice.”

“You don’t need a record—it’s in your head.”

I slipped the tape recorder back in my bag and took out a fresh notebook. A little smile played on his lips. It was the fall of 1973. I had come to write a book on the Yom Kippur War called Israel on the Seventh Day. A sadness swept over me realizing that the air in the room talked of death. I knew how badly the country would miss him.

“Master,” I asked, “will there ever be peace between the Arabs and the Jews?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“Not in my time,” he sat up in his bed. “But in yours and your children’s.”

“Where will it come from?” I pressed.

“Egypt,” he said.

“Egypt?” I was incredulous. “That’s where the fedayeen (terrorists) come from. Egypt starts every war. They’re the ones who throw the grenades into children’s homes. How can peace come from Egypt?”

He waved his hand as if brushing the thought away.

“Forget that,” he told me. “There is a whole generation of young people rising up who know we can cooperate. They still have diseases we cured fifty years ago. Our doctors and our scientists can help cure them. They have natural resources and raw materials that we need. Yes, there will be peace.”

I took his hand, knowing it was the last time I would see him. He died on December 1,1973.

Readers who may wonder at my recollections of whole scenes and dialogue may feel reassured to know that they come from the 350 notebooks I filled with descriptions and interviews recorded right on the spot in my own idiosyncratic version of short longhand.

They also come from my reports to Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, which began in Alaska in 1941 for eighteen months, and then continued through my years in Washington as his special assistant until January 1946.

Returning to journalism as a foreign correspondent in early 1946, my articles and photos have given me the eyewitness material I use here in covering the postwar years through the birth of Israel, and on to 1952, when Inside of Time ends as Eleanor Roosevelt asked me to show her how Israel was absorbing tens of thousands of new immigrants.

In these difficult days, with heartbreaking stories of suicide terrorists and innocent victims, I find it more important than ever to live and write inside of time. It does not mean living life without urgency and passion, or expecting immediate rewards. We must keep working for peace, fighting injustice, and raising our children and grandchildren to live with decency, dignity, and hope.

—RUTH GRUBER

NEW YORK CITY, OCTOBER 2002

Part 1

ALASKA

Chapter One

MISS GRUBER GOES TO WASHINGTON

On a halcyon spring morning in April 1941, I jumped out of bed in a small Washington hotel room. My mind was churning. At eleven o’clock, I was to interview Harold L. Ickes, the secretary of the interior. In a few days, I was to leave for Alaska to write a series of articles for the New York Herald Tribune.

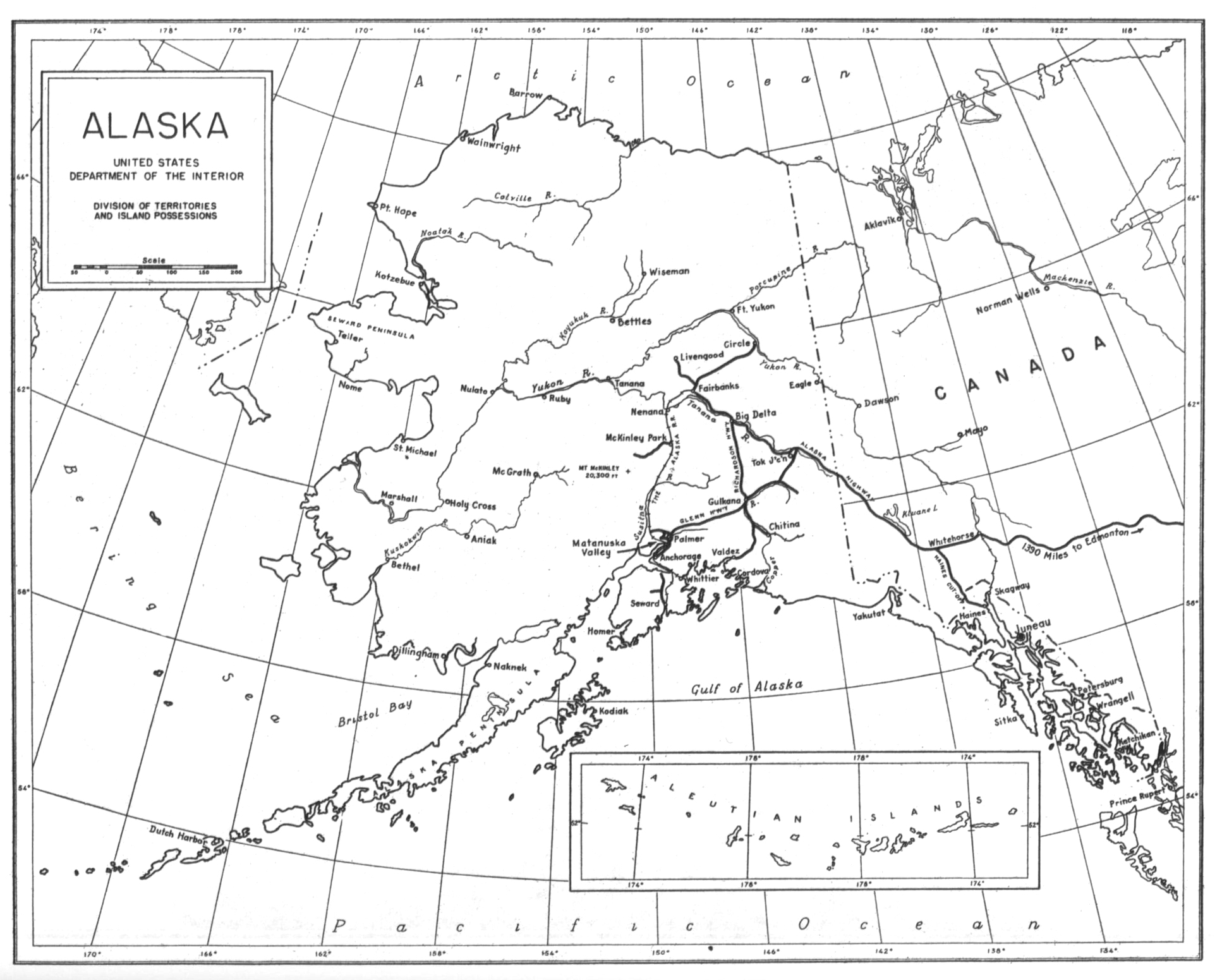

Interviewing Ickes was a must. Alaska, still far from being a state, was in his department.

What would he be like, I wondered, as I dressed carefully in a navy blue suit, white blouse, and a blue hat with an upturned brim of white satin. I wore dangling earrings and high heels, hoping they would make me look taller than my five feet two inches and more sophisticated than my twenty-nine years.

Long before eleven, I hailed a cab, drove through Washington’s quiet streets and stared at the Greek-style monuments with excitement. “He’ah you are,” the cab driver sang out. “Here’s Interior.” He stopped in front of an elegant building with bronze-sculpted doors. An attractive, dark-skinned elevator operator, immaculately dressed in a summer dress, rode me up to the sixth floor, and pointed me to the secretary’s suite.

Inside a waiting room with benches lined against the wall, Ickes’s appointment secretary sat like a sentinel guarding the gates. She took my name and motioned me to take a seat. The outer office was filled with men. One after another, she waved them through an inner door. I heard her calling them by their titles: Senator, Ambassador, Governor, Mr. Mayor. No one stayed in Ickes’s office more than ten or fifteen minutes.

Exactly at eleven, the appointment secretary, whose name I kept hearing was Ellen Downes, beckoned me. I followed her as she knocked at the door and then left me at the open entrance. I hesitated for a moment. Ickes sat at a desk at the far end, looking up as I began what would have been a two-block walk in Brooklyn. Even as I headed toward him, I noticed that he must have favored the color blue. The heavy drapes that looped around the windows from the ceiling to the floor, the chairs that encircled a conference table, the deep rug in which my high heels sank—all were blue.

In New York I had read whatever I could find about this former newspaper man/lawyer. As secretary of the interior, he had cleaned up a corrupt department. The Teapot Dome scandal about twenty years earlier had been in Interior under President Warren Harding. It was said of Ickes, who was unimpeachably honest, that he would fire anyone caught stealing even a postage stamp. He was saving the environment, conserving its beauty, guarding wildlife, fighting for minorities, especially Indians, building parks, changing the face of America.

He was sixty-seven, born in 1874 on a farm near Altoona in western Pennsylvania. His father was an alcoholic womanizer. His older brother was a bully. But his mother wielded the greatest influence on his life, teaching him to be self-sufficient, courageous, and a skillful organizer. She died when he was just sixteen, but her influence was his legacy.

Now, he came in from his Maryland farm before eight every morning, checking up to see who was not yet at work. The picture I had drawn in my head was of a New Deal Democrat who was politically liberal and socially a tyrant. Instead, I found myself sitting in a leather armchair next to a warm, approachable man who looked like the editor of a country newspaper. His body was small and round, his eyes glinted behind gold-rimmed glasses, his jowls moved when he turned his head. He had a pug nose and a pugnacious jaw.

“I’m glad you came,” he said. “Because of your book we tried out many of the things we’re doing in Alaska.”

A chill of excitement ran down my spine. My book I Went to the Soviet Arctic was published on September 1,1939—the very day Hitler invaded Poland. Two years later and it was influencing our government! I hoisted myself in the chair trying to appear cool. I squeezed my hands so he wouldn’t see them trembling.

“My wife, Jane,” he spoke the three words like a love song, “my wife, Jane, found it in a bookstore and told me, ‘Harold, you had better read this book.’ ”

I had seen newspaper pictures of his young, red-haired, beautiful wife, Jane, who was pregnant. In 1938, the press had gleefully exploded with the story of the sixty-four-year-old widowed secretary of the interior marrying the twenty-three-year-old member of the Cudahy meatpacking family. He had met her through his son’s wife. Somewhere I read that she had told an interviewer, “I would rather spend five years with Harold than forty years with a less exciting man.”

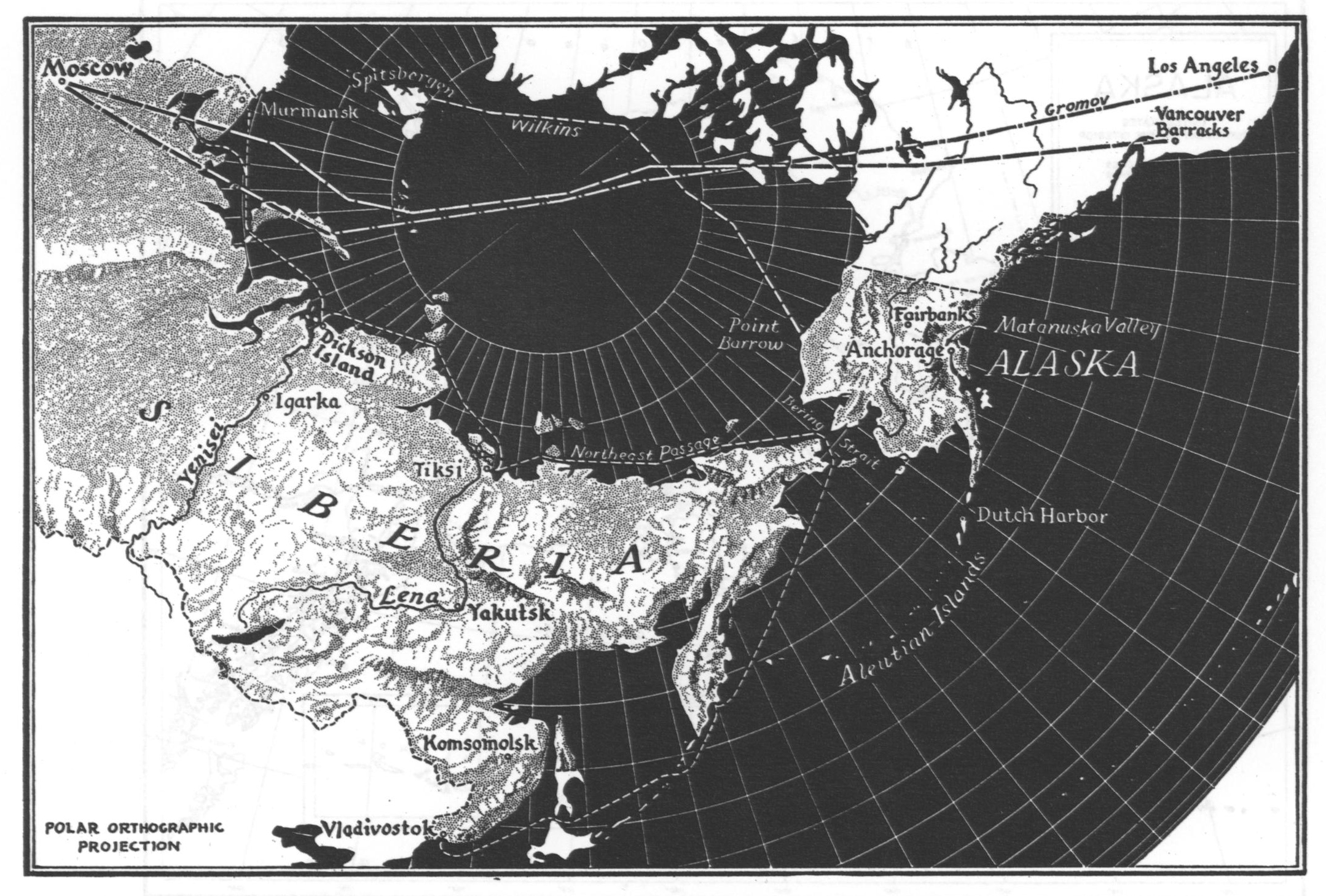

“So you’re leaving for Alaska for the Tribune? That’s good,” he said, wasting no time. “Alaska’s going to be very important once we get into the war.”

I nodded. “The war will teach people that Alaska is the shortest route for our planes to ferry guns and butter to Europe. And at the Bering Strait, we’re just three and a half miles away from Russia.” He sat silent, waiting for me to go on. I continued, “That’s why we have to populate it fast. But it’s that perennial contradiction when you’re opening new land. You try to conserve a frontier land and at the same time fill it with people who might lay it waste.”

“You’re right,” he said, “but time’s not on our side. Populating Alaska is a wartime priority.”

“That’s why the Herald Tribune wants this series now.”

He swiveled in his chair to face me directly. He was smiling. “Will you be going alone?”

“Yes.”

“You’re single?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Jane and I went to Alaska. The country is beautiful. I want to create more parks there to keep that beauty untouched. But Alaskans aren’t enthusiastic about what we’re doing. The spirit isn’t right up there. Most of the white people are only interested in making money and taking it out to spend in Seattle and California.”

He continued talking about Alaska, obviously enjoying his description of this huge empty land, bigger than Texas, one-fifth the size of the United States, with only thirty thousand whites and thirty thousand native peoples.

Then, silent for a few moments, he searched my face. I glanced surreptitiously at my watch. We had been talking for half an hour.

Now I waited for him to go on.

“Between you and me,” he broke the silence, “I’m very unpopular up there. Recently the legislature passed a unanimous resolution asking the president to accept my resignation, or if I didn’t resign, to fire me. When the Chicago Tribune read that resolution, they sent a reporter up there to dig up dirt. Today they’re starting a whole series of articles attacking me.”

Though I had just met him, I had begun to feel we had the same goals for Alaska. “What are you doing about it?” I felt outraged for him.

“It doesn’t matter. I can stand it. I’m glad you came to see me and I’m glad you want to go to Alaska. Don’t go for the Herald Tribune. Go for me.”

I felt blood rush to my head. I had come expecting to interview him for the Herald Tribune. Instead, he was suddenly offering me a job. What would it be like to work for the government? To work for such a man?

I was a child of the Depression. To be offered a full-time position was almost unheard of. Nearly everyone I knew was unemployed. If there were jobs, they went to young men, not to young women. True, I was lucky. I was part of the Herald Tribune family, with credentials and a serious byline, “Special Foreign Correspondent.” But I was paid by the article and the syndication. This would be different. A real job.

“How long would you expect me to stay?” I asked, though the words “yes, yes, yes” were ringing in my head.

“A year, maybe longer. You would be my field representative, reporting directly to me. Your work would be pretty much what we’ve been talking about—how to populate the territory, and at the same time conserve its natural resources and its beauty. You’d be making a social and economic study, and sending me reports as you go along.”

“Mr. Secretary, I would be honored to work for you.”

He pressed one of the row of buttons on his desk. Within moments, a solemn man with a pale face and pale brown hair entered.

“This is Mr. Burlew, First Assistant Secretary,” Ickes introduced us. Mr. Ebert Keiser Burlew always signed his name ‘E. K.’ “Dr. Gruber wants to go to Alaska and we’ve got to send her.”

Mr. Burlew’s voice was flat, emotionless. “We’re pretty low in funds, you know.”

Ickes was undaunted. “How about getting Colonel Ohlson to put her on the payroll of the Alaska Railroad?” He turned to me, a mischievous smile around his lips. “Careful. We’re horse traders.”

Some fifteen years later, I read in The Lowering Clouds (Volume I of The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes) his account of our first meeting.

Dr. Ruth Gruber … wants to go to Alaska and do a job there. She is a writer and lecturer and is the youngest Ph.D. in the world. Her book on the Soviet Arctic was very good indeed, although I have not read all of it.

Dr. Gruber is a very attractive young woman and is quite good-looking. I could not quite make out whether she is Jewish or not, but she may be.

Hmmm, I thought. Later, he told me that growing up in western Pennsylvania he hadn’t met a Jew until he was sixteen years old. But he must have had some kind of mystique about Jews. The legal department was staffed with brilliant young Jewish men. I once wrote him a letter with a New Year’s greeting in which I told him, “You don’t have an ounce of anti-Semitism in you.” He had written back, “Barney Baruch told me the same thing.”

Anyhow I confess that I fell for her line and decided that I would like her to go to Alaska. She wants to go at once and will stay a year if necessary. However, she has to be financed.

… In the meantime, however, Dr. Gruber got everyone by the ears down here. I suspect that she is an imperious young woman who does not stand on ceremony and wants to have her own way. Anyhow, she got Burlew sour on her and Mrs. Hampton and the people in Territories and Islands as well.

I chuckled. I knew I had made people angry because I was too impatient. I had wanted to cut all the bureaucratic red tape and get up to Alaska. Others in the department, I later learned, were asking, “Who is this dame from Brooklyn who sashays into the boss’ office and he gives her a job we would have given our eyeteeth for?” I went on reading in his diary:

However, I think that it is worth the experiment to send her to Alaska … it may be that Dr. Gruber has come at just the right time. If she comes back with some of the conclusions that I have formed, she will be in a position to do a great deal of useful publicity. Her point, which I think was well put, is that Alaska cannot be popularized in Alaska but must be popularized here. I think she can do it.

Chapter Two

FDR AND ELEANOR HOLD SEPARATE PRESS CONFERENCES

From Ickes’s office I taxied back to my hotel and telephoned Joe Barnes, my editor at the Herald Tribune. “Hi, Joe,” I tried to contain my excitement. “Guess what? I have a new job. I can’t go to Alaska for you. Harold Ickes is sending me.”

“Wow! Congratulations, Ruth,” he said. “That’s a real coup. But I’m disappointed. H. R. will be too.” H. R. was the name everyone called Helen Rogers Reid, the wife of Ogden Reid, the owner of the paper. “We were really looking forward to running the series,” Joe said. “But make sure to call me when you get back. We can run it next year.”

Next I phoned Brooklyn. Mama answered the phone.

“Put Papa on the extension,” I shouted. “I’ve got something to tell you both.”

“I’m on,” Papa said.

“Listen, the government is offering me a job.”

“Where is it?” Mama demanded.

“In Alaska.”

“At least Alaska is in America.” Mama took a deep breath. “With you, it could have been China.”

I laughed. “One day maybe it’ll be China.”

For several days I appeared in Mr. Burlew’s office only to be told by his secretary that Mr. Burlew had no word on when I was to leave. As a political journalist for more than a decade, I was no stranger to bureaucratic foot-dragging.

Five years earlier, on my second trip to the Soviet Arctic, I had spent weeks in Moscow trying to get a visa to the Yakutia Soviet Socialist Republic. Russia was a bureaucratic nightmare. Government agencies warred against each other until finally Otto Yulievich Schmidt, the czar of the Soviet Arctic, pulled a magic cord and I took off. My experience there should have immunized me against the slow motion of Washington bureaucracy.

To fill the time waiting for orders to leave, I began interviewing some of the bureau chiefs. All were men, generous with their time and advice, and one woman, Ruth Hampton, who was the assistant director of the Division of Territories and Island Possessions. Alaska was part of her province. A few days before meeting her I spent a whole morning with Felix Cohen, a tall, thin, bespectacled lawyer, the son of the famous philosophy professor Morris Raphael Cohen of City College in New York.

Felix told me how he had helped write a bill that would bring five thousand Jewish refugees from Europe and five thousand American settlers from the States to Alaska each year.

“Ickes was determined to help refugees,” Cohen explained. “The bill had a two-pronged purpose: to save refugees and to open Alaska.”

I was awed by how Ickes and his staff were linking the rescue of Jews with opening Alaska.

“What’s happening to the bill?” I asked.

He shook his head. “It never got out of committee. Ickes was livid when it was killed.”

“Who killed it?”

“So many. The isolationists and restrictionists in Congress. The labor unions who said every refugee you bring in takes a job away from an American. The anti-Semites. Even a whole group of Alaskans came all the way down here just to fight us.”

“Alaskans,” I blurted out. “Didn’t they see how five thousand refugees and five thousand Americans coming up every year would bring in doctors, teachers, pioneers, homesteaders—?”

I stopped speaking. His face was a mask of pain.

He spoke in a low voice. “The Alaskans said there was no anti-Semitism in the Territory now because there were only a few Jewish families in each town. Bringing five thousand Jews a year would start race riots.” Then, in a strained voice, he said, “They all helped to kill the bill.”

His words hung in the air as I left his office.

Still no word from Mr. Burlew. Evenings, I prowled the quiet unhurried streets of Washington. Along the Tidal Basin the cherry blossoms were exploding into pink-and-white balls of cotton candy. But my mind was not on the snowscape of cherry blossoms. I was consumed with getting to Alaska before we went to war, but right now the likelihood seemed far away.

Marking time, I visited friends in the Washington bureau of the Herald Tribune who invited me to President Franklin Roosevelt’s press conference in the White House. We waited in an anteroom outside the president’s office. I overheard reporters priming each other: “What’s your timetable? When are we going to war?”

The door to the Oval Office opened. My friends broke a trail through the herd of men, pushing me to the front of the president’s desk. His desk was littered with ashtrays, miniature horses, small boats, toys, and a long cigarette holder.

Up close Roosevelt was even handsomer than the rotogravure picture my father had hanging on the wall. If only Papa could be here. Papa adored Roosevelt. Papa, who had come here at sixteen from czarist Russia to escape pogroms, considered Roosevelt the greatest president in the greatest country in the world. How thrilled the whole family would be when I told him how close I had stood to the president.

I jotted a quick description of him in my notebook:

Sits comfortable and relaxed. The useless legs hidden behind the desk. Gray striped suit. Black-and-orange polka-dot tie. The weatherbeaten skin is a road map of black telltale marks of sun and wind and sailing. He beams that famous smile with its fascinating crooked teeth directly at you like a klieg light, making your heart stop.

The only ones seated were the president, who was reading papers on his lap, and his press secretary, Steve Early, who sat directly behind him. Four Secret Service men stood in the background. He had been wheeled in before we were allowed to enter. Journalists never mentioned his polio-ridden legs.

While he remained silent, continuing to read, my eyes swept around the crowded room. I recognized Walter Lippmann, the Herald Tribune’s most influential columnist, and Elmer Davis, later to become head of the Office of War Information.

“There are no other women here,” I whispered to one of my friends. “Why?”

“Roosevelt likes only men journalists at his press conferences. That’s why we thought it would be fun to sneak you in, and then get you right up front. Once you’re in, we figured they wouldn’t throw you out.”

I wanted to laugh, but the president, looking up from his papers, was talking of sending aid to Britain. Suddenly, here in the White House the surface calm of Washington vanished. Our minds were focused on the war as Roosevelt described the British standing alone against Hitler. There were hang-ups, the president complained, in rushing war equipment to help them. We knew that FDR wanted to get us into the war to help Britain and defeat Hitler, whose armies had already conquered most of Europe. Now in the spring of 1941, the war in Europe was heating up. Hitler’s U-boats were decimating the British fleet. Yugoslavia, trying bravely to hold out, had been overrun in a week and a half. Knowing how vulnerable and unprepared Alaska and the Philippines were, defense areas were being established around them. But Roosevelt couldn’t get the country behind him. Using the press conference, he involved us, maneuvering us to carry his message of frustration: The country had to move faster to help our closest ally and friend, the British.

Three months earlier, on December 18, 1940, Hitler had issued war Directive Number 21, “The German Wehrmacht must be prepared. Also, before the ending of the war against England, to crush Soviet Russia in an Active Campaign.” Hitler called the operation “Barbarossa,” a reference to the leader who had ruled Germany’s First Reich in the twelfth century and conquered much of Europe. Barbarians.

“I am not pointing with pride,” FDR’s eyes narrowed. “I am not satisfied.” He flung the word not at us like an angry prophet.

“How can you accelerate the work?” a reporter asked.

The president puffed his cheeks out as if he were thinking. Then he pulled his right hand over his head and scratched his left eye. “By using chestnut burrs.”

Even Walter Lippmann looked bewildered.

Roosevelt waited. The reporters did not move.

“You boys,” he said at last. “You know where they put the chestnut burrs on horses to make them go.” He threw his head back and laughed. The men roared with him. I was no farmer, but I could imagine what part of a horse’s anatomy was involved. Welcome to the boys’ club.

That night, unable to sleep, still raging that the mills of bureaucracy ground so slowly, I jotted notes swiftly. Perhaps, alone in his room at night, the president tossed in his bed as I was tossing now. If he had any misgivings or doubts, he never showed it. In his patrician voice, he said, “There are some smart people in this country—and in this room too.” He stopped and smiled as he said it, and you felt he liked you, trusted you, admired you—until he lashed out, “and there are liars, enemies, appeasers, and they are in this room too.”

You looked around to see which enemies he meant. He manipulated the reporters like a lion tamer in the circus.

Early the next day I was back standing at Mr. Burlew’s secretary’s desk. This time, Burlew himself came out of his office. Before I could say a word, he blurted, “We’re sending radiograms back and forth to Colonel Ohlson in Anchorage.”

I was about to inquire why my orders were moving so slowly, when Mr. Burlew said, “These things take time,” and vanished into his office.

What was causing the delay? Was it me? Was I trying to speed up the wheels of government? I knew my faults. I was restless, always fighting against time. What did I need to learn so that seasoned bureaucrats would not be as hostile to me as Mr. Burlew seemed? Or, I wondered, was there a whiff of misogyny and anti-Semitism?

One morning at ten, I entered the office of Ruth Hampton, the assistant director of the Division of Territories and Island Possessions. She was in her fifties—large, buxom, white-haired, and as icy as the glaciers I was impatient to see. I hoped she could speed up whatever maddening process was holding up my departure.

“The secretary suggested I read your book,” Mrs. Hampton told me. “I don’t know. I can’t get behind the word communist. I hate them so. I can’t bear to read anything about them, good or bad. They’re no different from those Nazis. I hate them all. To think those poor lovely people in the North you wrote about have to be victimized by those brutes.”

Sensing hostility, I thanked her and hurried out of her office. On the street, I hailed a taxi to the National Museum to meet Ales Hrdliçka, the anthropologist who had led a four-year expedition to Alaska in 1899.

Dr. Hrdliçka was a young seventy-two-year-old, short with soft smiling eyes. “So you were in the Soviet Arctic,” he beamed. “They’re doing a wonderful thing there in the intermarriage of the races, openly and willingly, not like our whites and Negroes. They’re creating a taller, stronger race, and bringing out very good things.”

I shut my eyes for a moment. In a half hour I had traveled the arc of Washington’s obsession with communism—from right to left, from Hampton to Hrdliçka.

“You are American?” he asked suddenly, squinting at me as if I were an anthropological specimen.

“Yes.”

“You are Jewish?”

“Yes.”

“Good. But don’t go to the Eskimos with those fingernails and red lips. And that hat.… They’ll be afraid of you. They’ll disappear right off the street.”

I laughed. “I don’t expect to dress this way in Alaska.”

He seemed not to hear me, as he continued. “Most of the stuff written about Alaska is trash. This is not against you, but against the rhapsodic stuff women novelists write. They go only where the tourists go.” He flung his arms out and raised his eyes to the ceiling as if he were imitating their rhapsody. “But few people ever go where you will go—”

Rapidly I changed the subject. I found his views amusing but I hadn’t come to interview him on women novelists. “What future do you think Alaska has?”

“No future at all,” he tossed the words at me.

Surely, I thought, he’s teasing me. “I think Alaska has a brilliant future—if we can get people to develop it,” I said.

He wasn’t teasing. “You can lead a horse to water … you know the rest. But it’s good you’re going. If you’re the right kind of person, you will enrich your life up there. Your whole life will be different. It won’t make you a good person, but it will make you a better person.”

His enthusiasm, quixotic as it was, lifted my spirits. I taxied back to the Interior Department to keep my next appointment. It was with Mike Straus, Director of Information for Interior.

Straus paced the floor in front of me, a burly giant whose bronze face looked more like an American Indian’s than a smart Jewish newspaperman who had come out of Chicago with Ickes. I liked him instantly.

“You’re young to be the next target of a lot of political machinations,” he said. “Be prepared. The big fish canners and gold miners up there hate Ickes, and they’re going to pick on anyone he sends. Better get yourself ready for it.”

I felt no fear.

He continued pacing. “I think we’d better send out an announcement about your appointment. I don’t think we should play you up as ‘Youth Personified’ or ‘the Lady Explorer.’ We’ll keep it on a broad base that you’re going up to make a social and economic study—”

“And that’s the truth. I want to find new ways to help open the Territory—”

“Okay, okay. But we’ve got a campaign to work on,” he said.

One day, I attended one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s all-women press conferences. Her conferences were a gentle poke in the stomach to her husband for his all-male conferences. Little I had read about her prepared me for her presence, or for the mixture of sadness and strength in her face. Her high voice and buck teeth took nothing away from the passion that fueled her words.

The women asked her questions about welfare, childcare, the evils of poverty, and the role of women in politics. She answered with skill and honesty, often admitting, “I really don’t know, but I’ll try to have the answer next time we meet.” Here she was—a journalist among journalists. Even in the way they questioned her, the women journalists showed their admiration and affection. She was never cynical or judgmental, never mean or cruel. She won their trust, and they showed it in the stories they wrote about her.

But her enemies were legion. They hated her power and her influence on the president. No First Lady had ever acted as she did—popping up everywhere, in mines wearing a miner’s helmet with searchlights, in factories, in airfields, in army posts, and aboard naval war ships. She was always speaking out with courage, always concerned with human rights. Yet, she was constantly lampooned by reactionary cartoonists and writers, especially Westbrook Pegler, a columnist syndicated by the Hearst newspapers. Later when I was “Peglerized” for working for Ickes, she told me, “You learn how to handle people like him. You ignore them.” Now in her press conference, surrounded only by women, I hoped she took comfort from the women and, of course men, too, who came to her defense.

At long last, Mr. Burlew called me to his office. “Colonel Olhson sent the radiogram we’ve been waiting for. He’s ready to put you on his payroll.”

“So I can leave immediately?”

“Not so quick. You have to fill out these civil service papers, questionnaires about your educational background, jobs you’ve held, things you’ve published, everything—”

That day, doctors in the Public Health Service examined my eyes, my ears, my throat. I was fingerprinted and later learned that J. Edgar Hoover himself assured Ickes that I was clean.

At nine the next morning, I was back in Mr. Burlew’s office. It was Good Friday and Passover, April 11, 1941.

“We wired Colonel Ohlson your assignment as of today,” Mr. Burlew said. “You can take the oath of office right now.”

I raised my hand, swore to uphold the Constitution of the United States and was sworn in as “Field Representative of the Alaska Railroad.”

Outside I flagged a cab for Union Station and a train to New York City. I was determined to reach Brooklyn in time for the first Passover seder.

Papa, dressed like a noble Jewish king in a white caftan and a white yarmulke, led us in the prayers and told the story I loved, of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt up to the Promised Land. Ickes, I thought, was trying to lead terrified Jews out of Hitler’s Europe. But he, like everyone else in Washington, had failed.

I looked at Mama, short and strong, in a freshly starched white blouse, dark skirt, and spotless apron, ladling out the holiday food she had cooked all day. I loved listening to my three tall handsome brothers, Bob, Harry, and Irving, singing the prayers with enthusiasm. I sat close to my sister, Betty. Until she married Sam Sobel, the medical student she had fallen in love with at New York University, we had shared a bedroom and all our secrets.

My parents, like millions of immigrants, had worked to make us educated, honest, and decent human beings in a country where you could be anything you wanted to be. Education was their highest priority, but my mother had to quit school in the eighth grade. She was needed to do the laundry for the newcomers who stayed at her parents’ apartment for two dollars a week.

I shut my eyes listening to the prayers. I was home.

But Mama was worried about Alaska. “It’s so cold,” she shuddered. “God forbid, you could even freeze to death in all that ice and snow.”

“It isn’t all ice and snow.”

She hardly heard. “So when are you going to stop running? You’re not so young anymore, you know.”

Mothers and daughters, I thought. On good days we embrace like dancers clinging to each other in a Spanish tango, and on bad days we condemn each other in a tug of war. “Why can’t you be like the daughters of my friends?” my mother asked rhetorically, knowing I had no answer. “They get married. They have children. They have a nice easy life. But you—you’re too busy traipsing around the world.”

I realized she wanted me to fulfill her dreams for me. But I couldn’t, though I knew I was giving her pain and anxiety. I tried to make her understand. “Look at it this way, Mom. Maybe I can help people who have no jobs, or who don’t know what they want to be. If I handle this job well, maybe I can help them build a new life for themselves.”

“So maybe you could build a new life for yourself.”

I tried to forestall the tug-of-war. “Some day, Mama. But not now. I’m leaving in two days.”

I could hardly wait.

Chapter Three

A CONTROVERSIAL BATH

The whole family helped me pack a suitcase with winter and summer clothes. I slung my Leica, and my eight-millimeter movie camera over my shoulder, picked up my portable typewriter, and walked around kissing everyone good-bye.

“Don’t forget this,” Mama handed me a brown grocery bag with a jar of prunes she had soaked overnight in my father’s best scotch. “In case you have a headache or get sick while you’re traveling.” Inebriated prunes were Mama’s cure for every disease. It was the gift she gave me before I left on any assignment.

Papa kissed me on the forehead. “Go with God and be careful.”

In the comfort of a roomette on the Pullman train, I spent five days reading, planning, reveling in the beauty of America, until the train reached Los Angeles.

I was to spend the night in Los Angeles, and then continue by train up the coast to Seattle, where I would board a ship for Alaska. In the L.A. station, I walked to a newspaper stand. A San Francisco tabloid called This World caught my eye. Was it possible? On the front page was a photo of me with the caption:

DOCTOR GRUBER

WANTED TO TAKE A BATH

ZDRAVSTVUITYE

The article described how Republican Congressman John Taber of New York had interrupted Congress’ discussion of the budget for the Interior Department. Holding up a copy of I Went to the Soviet Arctic, he barked, “It’s time to stop the propaganda of communism. Any of us who vote to pay this woman’s salary is not fit to sit in the House of Representatives!”

Representative Jed Johnson, a Democrat from Oklahoma, jumped to the defense, asking for a quotation from the book. “How can we prejudge a woman without even giving her an opportunity to be heard? … Even the worst criminal has his day in court.”

Obviously no one in Congress had read the book. There was a long silence.

“Until someone reads it,” Johnson announced, “I’m not going to condemn her.”

Noah Mason of Illinois quickly read the last sentence: “But I know that some day I shall go back and bathe again in the Yenisei at Molokov Island … swim in the Arctic Ocean, and come back to a steaming breakfast shouting, Zdravstvuitye (which means hello).”

The thought of a government official shouting Zdravstvuitye was enough for the House. It quickly voted 64 to 49 to remove me from the Interior Department’s payroll.

North Carolina’s Alfred Bulwinkle, a Democrat, plaintively murmured, “The only thing she said is she wants to take a bath.”

I found a seat in the railroad cafeteria. So this was what Mike Straus had tried to prepare me for.

“It’s a rotten lie!” I heard myself say so loudly that people at nearby tables turned to look at me. I was angry and frightened. What did it mean? Was I fired already?

Surely they knew I was no communist. If they had only read the book, I thought, they would have known that I had written for the leading newspaper of the Republican press, the New York Herald Tribune. Where had they gotten their ideas? Certainly not from the book. If I had been a communist, the Russians would never have let me go to the Arctic. They knew that a communist would have been prejudiced in their favor, and wouldn’t have been believed in the States.

I checked into the Women’s Club of Los Angeles. As the morning wore on disturbingly, newspapers began calling for statements on my political views. I thought how ironic it was. I was no political evaluator; my interests were people. The only thing revolutionary in the book, I thought, was its proof that any nation’s share of the Arctic needn’t any longer be a barren, uninhabitable wasteland. The great overthrow that I recommended was the overthrow of medieval prejudices against the North by people of more southern descent.

I telephoned Ickes. He was jovial. His wife, Jane, had just given birth to a son, Harold Jr.

“How’s the communist?” Ickes laughed.

“She only wants to take a bath,” I said.

“Communists don’t take baths,” he joked.

“I know, that’s what confuses me.”

“It’s not you they’re after, it’s their way to get me,” he explained. “Get everyone important you know to write me a letter. I’m going to fight it in the Senate.”

Ickes sounded like a boxer dancing in the ring. This was what he loved. Only Ickes, I thought, would have taken on the fight for someone he hardly knew. Most cabinet members would have said, “Sorry kid, can’t help you. You’re out.”

I got to work. I realized what it meant to have friends. Wires and letters poured in from people like Professor George Cressey of Syracuse University; Quincy Howe, editor at Simon & Schuster, the publisher of my book; Mary Beard, historian, and the director of the CBS Lecture Bureau. My brother Harry cancelled his appointments and trudged around New York picking up the written recommendations. Of all the letters and telegrams that came in, the gesture of support that gave me the most confidence and strength was from the Arctic explorer and author, Vihljalmur Stefanson. Stefanson wrote:

I have known Dr. Gruber for seven or eight years and have frequently heard her discuss political and social questions. Her views are essentially those of a New Dealer—very strongly anti-Fascist, strongly anti-Communist, and certainly not farther Left than those of President Roosevelt in his fireside chats and messages to Congress …

I have seldom seen book reviews that were more uniformly favorable, and do not remember that one of those I read suggested that she might be a communist or might have communist leanings. There were several who complimented her on not taking sides—on being objective and pointing out the favorable as well as the unfavorable sides of life in the country she traversed.

A call came from the Herald Tribune. It was Helen Rogers Reid.

“Ruth, this thing is a political move, and utterly ridiculous.” She repeated what Ickes had said. “It’s an attack against Ickes and you happen to be a pawn. I’m writing a letter of outrage.”

The next day the Herald Tribune ran an article that announced:

DR. RUTH GRUBER

PRAISED, OUSTER

DRAWS ATTACK

FRIENDS INDIGNANT AT HOUSE

FOR DROPPING HER FROM

PROPOSED ALASKA SURVEY

Several days later, Ickes entered the Senate chamber armed with a fat briefcase of letters and affidavits. He never opened it.

“I don’t believe,” he thundered, “that a citizen of the United States—which of course Dr. Gruber is—becomes a communist by visiting Russia.” He described the action of the House as “a reflection upon our democratic form of government. None of us can afford to let such fabrications go unchallenged.”

Senator Bankhead (Tallulah’s uncle) asked, “Do you know what race she is a member of?”

Ickes answered, “I do not know. I never asked her that. I have seen her twice. She looked like an American.” He quoted from the Los Angeles Times. “She has won the friendship and admiration of explorers and learned folk all over the world.”

In the end, it was Ickes’s wit that won the senators. They began to laugh as he pointed out that Herbert Hoover and Shirley Temple had both been to Russia, and they were not communists.

He sent me a telegram after the hearings, “You may proceed to Alaska with the understanding that if the language eliminating you from the Interior Appropriation Act is continued it will be necessary to recall you. After my statement before the Committee I do not believe this will occur.”

The next morning I boarded a train to Seattle.

Chapter Four

SCHOOLMARMS AND WHORES

The morning after my arrival in Seattle, I drove down to the docks of the Alaska Steamship Company, ready to sail at nine for Alaska. The ship was to leave an hour late, officials said. At ten, it was to be an hour later. At eleven, it was set to sail at noon. Finally, sometime in the afternoon, amid shrieking of whistles, grinding of cranes, rather sparse flurries of confetti, and people waving from the narrow wooden pier, we departed. The SS Denali was finally heading north.

A light mist fell on my face as I stood at the rail watching the ship pull out of the harbor. The ship nosed around the great industrial buildings of Seattle on beyond Vancouver, and pushed leisurely through the thick green timbered islands of the Canadian archipelago. A few hours north of Vancouver, and you were in a northern jungle of islands and fur-clad fjords, hidden bays, and circling inlets. I breathed in the clean washed air and the sweetness of evergreens along the banks. We were on our way to Alaska’s Inside Passage.

Soon the deck was alive with construction workers, sourdoughs (the name for early Alaskan settlers), fishermen, and women of different ages, some in elegant coats and high heels, others in sneakers and slacks. I wore slacks, too, and a sweater and low-heeled shoes to walk the decks.

In Seattle, a steamship officer had prepared me, “There are only two kinds of women going on that steamer—schoolmarms and whores,” he said. “The purser sizes them up when they come aboard and seats them according to their profession. He never guesses wrong.”

It was on that ship sailing to Alaska that I got my first intimation of the special brand of Alaskan humor, its virility, its enormous lies, its rich Bunyonesque imagination. The run from Seattle to Ketchikan is misnamed. It ought not to be called “The Inside Passage,” but rather “The Munchausen Tour.” The officers on the ships, and most of the old-timers, have huge and lusty fun at the expense of all the newcomers. Each year the tall stories grow taller, the bears bigger, the ice worms slimier, and the cold winters colder. At least half the misinformation taught to children by unsuspecting schoolteachers who have taken summer cruises to Alaska must be laid at the cabin doors of men like the Denali’s Swedish pilot.

A round, middle-aged sailor with his flaming red hair, his pipe, his thick brogue, and his joy in fooling all newcomers, especially schoolteachers, was famous on the run. Almost everyone had an anecdote about him that made you roar. I was with him one afternoon, walking the deck in the silver sunlight, when someone came up to him.