Acknowledgments

I WOULD LIKE TO give thanks to the following people for their generosity in making this book possible:

Chauncey Parker, Lisa Palumbo, Mark Desire, Joseph Calabrese, Laurey G. Mogil, M.D., Joyce Slevin, Bob Slevin, Luke Rettler, John Cutter, Jennifer Wynn, Stephen Hammerman, Arthur Levitt, Mark Graham, Anthony Papa, Mitchell Benson, Peter Neufeld, Jim Dwyer, Peter Garuccio, John Hamill, Steve Kukaj, Peter Walsh, Charlie Breslin, Ron Feemster, Svetlana Landa, Daniel Perez, Charles Shepherd, Leon Maslennikov, Katya Zhdanova, John Nelson, Ron Kuby, Nelson Hernandez, Joel Potter, Vicky Sadock, Sam Bender, Daniel Bibb, Mark Stamey, Bilial Thompson, Shqipe Biba, June Ginty, Bob Stewart, Kevin Walla, John McAndrews, Kim Imbornoni, Chris Smith, Tom Grant, Ed Rendelstein, James Watson, Molly Messick, David Segal, James McDarby, Steve Lamont, Steve DiSchiavi, Darryl King (the real one), Sophie Cottrell, Richard Pine, Michael Pietsch, and Judy Clain.

I would also like to give a special tip of the fedora to my old neighbor and friend Jim Knipfel for his graciousness and his excellent books, including Slackjaw and Ruining It for Everybody.

All of the above are hereby absolved of all responsibility for any factual mistakes made between these two covers, as well as for the character defects and crimes of moral turpitude described therein. All of those truly belong to the author.

A Biography of Peter Blauner

Although Peter Blauner (b. 1959) grew up on Manhattan’s East Side and attended the prestigious Collegiate School for Boys, he has always been drawn to the dark side of city life. “Being a kid during the fiscal-crisis seventies, I saw how things could change and you could go from the high to the low very quickly. Which is a very good lesson in humility and an even better one for writing crime fiction.”

Influenced equally by the films of Sidney Lumet and Martin Scorsese, the burgeoning punk rock scene, and the split-lip school of American pulp fiction, Blauner began writing short stories in high school and while still in college got a summer job assisting legendary newspaper columnist and author Pete Hamill. “He gave me a master class on what it means to be an urban writer. He taught me to always get your notes on paper right away, always ask the hardest question you can think of, and always listen carefully to the last thing somebody says to you.”

After graduating from Wesleyan University in Connecticut in 1982, Blauner returned to the city and began working at New York magazine, where he apprenticed with Nicholas Pileggi, author of Wise Guy and screenwriter of the film Goodfellas. Over the next few years, Blauner developed his byline for the magazine, writing about crime, politics, and other forms of antisocial behavior. But, he says, “My real goal was to train myself to become an urban novelist. I wanted to write stories that were suspenseful and compelling, but that also tried to capture what’s funny, surrealistic, and occasionally beautiful about city life.”

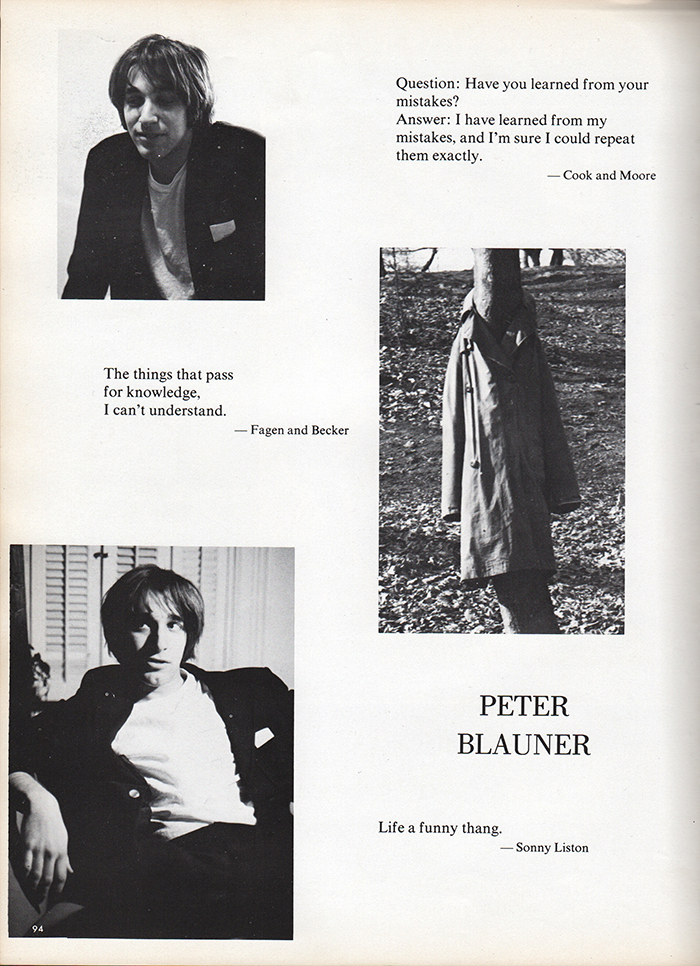

He decided on an approach of full-immersion research, which he has continued throughout his writing career. In 1988, he took a leave from the magazine and became a volunteer at the New York Department of Probation, so he could write about the criminal culture of the era from the front lines. The result was his debut novel, Slow Motion Riot, which was published in 1991. It went on to win the Edgar Allan Poe Award for best first novel and was named one of the “International Books of the Year” in the Times Literary Supplement by Patricia Highsmith, who called it “unforgettable.”

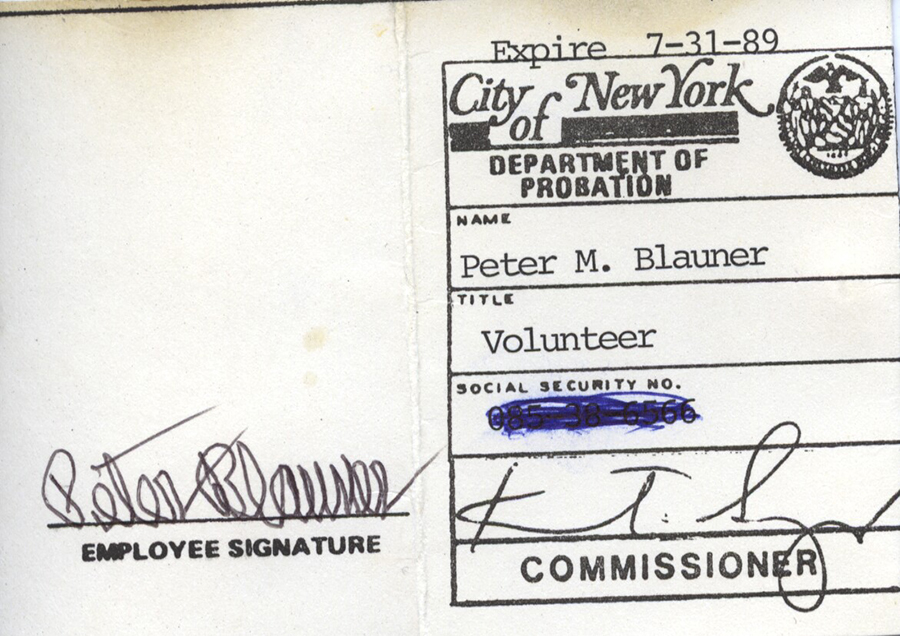

Soon after, Blauner turned his attention to fiction writing fulltime, and his next novel, Casino Moon, was a kind of update of the classic noir pulp genre, set in the Atlantic City boxing world and published in 1994. After his time in Atlantic City researching Casino Moon, he returned to New York and spent a year working at a homeless shelter to research The Intruder, which was published in 1996 and became a New York Times bestseller. For his next novel, Man of the Hour, published in 1999, he anticipated the reality of 9/11 by writing about misguided notions of heroism and Middle Eastern terrorism in America. Four years later, he shifted gears and wrote The Last Good Day, about a murder in a quiet Hudson River town and the resulting social fissures among the people who live there.

Blauner’s most recent novel, Slipping Into Darkness (2006), found him back on the city streets creating a modern urban mystery. It tells the story of Julian Vega, a bright young immigrant’s son, locked up in the early eighties for killing a female doctor on New York’s Upper East Side. Twenty years later, Julian is released from prison and another female doctor is killed under strikingly similar circumstances. Only this time, the evidence doesn’t point to Julian at all—it points to the woman he allegedly murdered two decades before. And the detective who arrested him in the first place, Francis X. Loughlin, is left to wrestle with the possibility that he ruined the life of an innocent man. The book earned the strongest reviews of Blauner’s career, with everyone from Stephen King to the New York Times ringing in, and introduced him to a new audience.

More recently, Blauner has branched out into television work, writing scripts for the Law & Order franchise, and also into short fiction. His short stories have been anthologized in the Best American Mystery collection and on NPR’s Selected Shorts from Symphony Space. He continues to live in Brooklyn with his wife, Peg Tyre, author of the bestselling nonfiction book The Trouble With Boys, and their two sons, Mac and Mose.

Blauner grew up in the New York City of the 1970s and started writing fiction while a student at the Collegiate School for Boys. “I became a writer right before Mother’s Day when I was fifteen: I saw a little girl at Gimbel’s Department Store trying to pull her dress down, and heard her nanny say, ‘Stop that, you’re as bad as your mother.’”

For his first novel, Slow Motion Riot, Blauner immersed himself in research, spending six months as a volunteer at the New York Department of Probation.

For his fourth novel, Man of the Hour, Blauner traveled Jerusalem and the West Bank to get a sense of his characters’ background stories. This photograph was taken by a shepherd at the sheep market outside of Bethlehem.

Since 1989, Blauner has been married to bestselling author Peg Tyre (The Trouble with Boys, The Good School). They have two sons.

In recent years, Blauner has been working in television, as a writer and producer for the Law & Order franchise.

1

TIME WAS IN a cage, a yellowing Bulova clock with a hatchwork of thin silver bars across its face.

The boy sat in the cinder-block room, as fragile as an egg in a carton, staring out into space, the needle of the second hand jerking in tiny increments above him. A red-and-white tie was knotted at his throat and a green book bag sat by his feet. His long eyelashes fluttered and a wispy virginal mustache, no thicker really than the hair on his arms, twitched on his upper lip.

He looked more like twelve than seventeen. Too chicken-chested to have done the kind of damage they were talking about. Nine of the fourteen bones in the girl’s face had been shattered, leaving just a pulpy maw between her hairline and lower jaw. They couldn’t even use dental records to identify her: her brother did the ID based on a mole on her thigh. The mother couldn’t bear to look. There was minor vaginal bruising, but what disturbed Francis X. more for some reason was the injury to her right eye. Something had pierced the lid, spilling the aqueous humor that had made the iris blue.

“He lawyer up yet?” Francis watched the boy through the one-way glass.

“No, but he’s thinking about it,” said his sergeant, Jerry Cronin. “He’s no dope, this kid.”

The boy’s fingernails drummed on the wooden tabletop, a little lopsided rumba beat. Hearing the echo in the empty room, though, he stopped and stared into space again, vaguely aware of being observed. His slender shoulders rose and fell in his maroon parochial-school blazer, sagging with the weight of accumulating time, two small red scabs on his chin plainly visible.

“Sully get anything out of him?”

“You know Sully.” The sergeant made a hissing sound. He was a small tight man, rapidly becoming smaller and tighter. “He’s got a touch as soft as John Henry. He came on hard and tried to put the fear of God in the kid. It was mutually decided another approach was needed.”

“So you giving me the keys or putting me in the rumble seat?”

“You’re getting the keys. With conditions.”

“Yeah?”

“Grown-ups are watching.”

Francis saw the Bosses gathering in the office down the hall like crows on a phone wire. Al Barber, his father’s friend from the First Dep’s office, talking to Robert “the Turk” McKernan himself, the chief of the department. No longer creatures of the street, but products of administration. Reflexes dulled, bodies thickened, eyes shrinking as they became more adept at spotting threatening memos than concealed weapons.

Francis locked eyes with McKernan for a half-second before the chief closed the door. “He don’t like me. The Turk.”

“Of course he don’t like you,” the sergeant said, shrugging. “Two years out of Narcotics, eighteen months off the Farm? Get the fuck out of here. You wouldn’t even be standing here if it wasn’t for your old man. But I told him, honestly, ‘The kid’s a fuckin’ great detective.’ I reminded him you got the Harlem Meer shooter and the one threw that little girl off the roof. I said, ‘You put Francis in a room with a guy, he’s gonna give it up. Best interrogator I’ve ever seen. Great natural talent, like Mantle hitting a baseball or Pavarotti singing opera. We got people talking over each other to tell him what they did.’”

“So he said all right?”

“Fuck no,” said the sergeant. “He still wants you out of there. But Barber and me ganged up on him, and the old man put in a good word. You get one shot.”

“Thanks, Sarge.”

“Don’t thank me. You make me look bad, you will rue the fucking day, my friend.” The sergeant tugged his sleeve. “Francis, one other thing.”

“Wha?”

“Sully never got around to reading him his rights. Bosses are a little concerned, Julian being seventeen and all.”

“I’ll dance around Miranda like Fred Astaire.”

Francis brushed past him, picking up a black canvas bag and putting his game face on. Not letting on the fact he was bothered. Wha? Just because the story had led the news for two days running? Just because the mayor and the police commissioner had already both given press conferences? Just because everyone was acting as if he, Francis X. Loughlin of Blackrock Avenue in the Bronx, would be personally responsible for a third of the city’s tax base relocating to the suburbs if the killer wasn’t caught by this weekend? Just because this was his best shot at turning things around after his little stint in rehab? Just because he’d met with the girl’s family and personally promised he’d do right by them? Just because the old man had interceded on his behalf and would probably be up here any minute, looking over his shoulder?

He stepped into the interrogation room and the door closed behind him with a cool unnerving clunk.

“Whaddaya reading?”

Julian Vega looked up from the book he’d pulled out of his bag, like a fawn peering out from behind a thicket, and then shyly raised the futuristic-looking silver-and-black cover of a book called Childhood’s End.

“Arthur C. Clarke. What is that, like, sci-fi?”

“It’s the third time I’ve read it.” Julian looked sheepish. “It’s not the greatest writing, but every time I understand it a little better.”

“What’s it about?” Francis eased himself into a higher seat across the table, knowing the Bosses were lining up on the other side of the glass, ready to second-guess him.

“The Overlords.” The boy’s voice was too husky for his scrawny-ass build. “They’re these superintelligent aliens who just show up and act like they’re going to save the earth from war and disease, but then it turns out they’re running a whole other game.”

“There’s always a catch, isn’t there?” Francis picked up the book and studied the back cover. “I read a lot myself. But usually more like biographies and history books.”

“That’s the past. I like to read about what hasn’t happened yet.”

“Hmm.” Francis let that last phrase hang for a few seconds before he put the book facedown and stared at Julian, establishing the unspoken ground rules: Your only way out is through me.

“So you know why we asked to stop by here today. Right, Julian?”

“Yeah. The other guy told me. You wanted to talk about Allison.”

Francis took out a yellow legal pad and put it on the table between them. They both took a moment to contemplate the invisible third presence in the room.

In family pictures, she was a little heartbreaker. All wild red hair and smoky eyes, fair freckled shoulders and cloud-parting smiles. You could see why she was still getting carded at twenty-seven. She looked barely older than the kids she was taking care of in the pediatric ER. All the other doctors and nurses he’d interviewed at Bellevue made a point of saying that she didn’t have to stoop much over the examining table. Everything was eye level with her. No matter how much the parents were screaming or freaking out in the doorway, she never raised her voice or resorted to baby talk when she had to put in a stitch or set a bone. She just talked to kids as though she were one of them.

Not that she was any Heidi of the hills—Heidi probably didn’t have expensive black Dior underwear in her dresser or a picture of Keith Hernandez, the ’stache-wearing Mets first baseman, taped to the bottom of her mirror or E-Z Wider rolling papers in her night table. On the other hand, Heidi might not have stayed after her shift with an eleven-year-old boy who had brain cancer, holding his hand and reading inappropriate sections out loud from Mad and Cracked. And three days ago, somebody hit her so hard with a claw hammer that one of the tongs went up into her frontal lobe.

“Does your dad know you’re here talking to us?” Francis asked, knowing the boy had been picked up by Sully at lunchtime outside the St. Crispin’s School on East 90th Street.

Julian shook his head. “I called, but it’s hard for him to hear the phone sometimes when he’s working in the basement.”

“He’s the superintendent of the whole apartment house, right?”

The boy allowed himself a quick proud smile. “Yeah, he takes care of everything. Seventy-two apartments.”

“Okay, that’s fine. It’s just a formal thing we have to go through whenever anybody comes in to help us. You know, ‘you have the right to an attorney,’ blah, blah …”

Francis could almost hear the sigh of relief from behind the glass. Up until a few years ago, he probably couldn’t have gotten away with questioning a high school senior without a grown-up present. But then that little psychopath Willie Bosket murdered a couple of subway riders for the hell of it when he was fifteen and—presto change-o!—a new law was born.

“And then we usually say something like”—he dropped his voice into his best mock-Dragnet register—“‘if you can’t afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.’ You know, all that bullshit. By the way, did you try calling your mom?”

“She’s dead.” Julian folded his hands on the table.

“Really?”

“Yeah. Long time ago. Cancer.”

“When you were how old?”

“Four.”

“I lost mine when I was nine.” Francis said.

“For real?”

Francis rested a hand on his gut. “I had my First Communion in her hospital room four weeks before she died. …”

He sat back and waited. Other guys had simpler ways of getting a rapport going. But sometimes a pack of smokes and a White Castle burger weren’t enough. Real scars had to be displayed. Wound psychology. You needed that shock of recognition to get a man to put his guard down.

“I still pray to Saint Christopher for my mom,” the boy said softly, reaching under his collar and showing Francis part of a chain around his neck. “My father gave me a medal.”

“Same difference.” Francis nonchalantly pulled out the Miranda card for Julian to sign. “I know how it goes. You’re always wanting something nobody can ever give you back. Sometimes you don’t even know what it is. You just want. Sign here, please.”

The long lashes fluttered and a shiny spot formed in the corner of Julian’s eye. He sniffed and glanced down at the card in embarrassment.

“But it’s always the same thing, isn’t it?” Francis said, distracting him. “You just want what everybody else has.” He nudged the card. “It’s all right. You don’t have to write your whole name. Just put your initials.”

Trying to clear his eyes with the back of his wrist, Julian scribbled next to the warning, glad to be doing something that looked adult and purposeful.

“I see you’re doing a pretty good job of looking after yourself,” Francis said, tugging his attention back lest Julian start reading too carefully. “You should’ve seen me when I was your age. I was a mess. My shirttails were always out. My hair never got combed. My shoes were always falling apart.” He chuckled knowingly. “You ever do that thing where you have to write your name on your clothes in Magic Marker because you don’t have anybody to sew a label on for you?”

“Sometimes, but I still got my papi taking care of me. We kinda look out for each other.”

Francis nodded, getting the picture. The widower and his son living together in the basement apartment. The boy carrying his father’s toolbox, always breaking out the wrench and the pliers before it was time to use them.

He put the Miranda card back in his pocket, mission accomplished. “So Julian. You were working in Allison’s apartment the night before—”

“Hoo-lian.”

“Ha?”

The boy looked abashed. “My parents called me Joolian instead of Julio, ’cause they didn’t want me to sound like every other Puerto Rican kid on the block. But then I started getting the crap kicked out of me in middle school, so my dad started calling me Hoolian the Hooligan.”

“I hear that.” Francis half saluted. “You can imagine what it was like going to Regis with a name like Francis Xavier Loughlin.”

The peach fuzz mustache jerked. “Really? You went to Regis?”

“Four years.”

“I think we played you in soccer last year.”

“Probably.” Francis humored him. “Anyway. You told Detective Sullivan you were in Allison’s apartment the night before.”

“Yeah. The ball cock wouldn’t rise.”

Francis heard what sounded like a cough behind the glass. “I beg your pardon?”

“The toilet tank wasn’t filling properly. Looked like it was leaking. So actually what I did was, I tightened the jamb nut. Then she could build up some serious pressure and get a nice strong three-point-two-gallon whoosh. You could’ve flushed a cat down that sucker.”

“I see.” Francis nodded and reached into the canvas bag he’d brought in the room. “Hoolian, I want to ask you something. This yours?”

He dropped a Ziploc evidence bag on the table between them. It deflated with a slow pouff, revealing the steel claw hammer inside. The cloudiness of the bag obscured fingerprint powder on the black rubber grip and the spots of dried blood on its head.

“Guess so.” Hoolian rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “I must’ve left it in her bathroom. Where’d you find it?”

“In the fire hose storage compartment, downstairs.”

“Damn. How’d it get there? I thought I left it in the bathroom.”

Francis shrugged, not letting on that Hoolian had just admitted the murder weapon belonged to him. “So you told Detective Sullivan that you stayed and talked to Allison awhile after you were done with the toilet.”

“Yeah, you know, we hung out sometimes. We were, like, you know, friends.”

“Friends?”

“Yeah …” Hoolian pushed up in his seat, a little disconcerted. “She was … a good person. We talked a lot. She was helping me write the essay for my college application.”

“Yeah? Where you applying?”

“Columbia. My father always wanted me to go there.”

“Good for you.” Francis stuck his lip out. “I’m just a Fordham guy myself.”

Slowly the hand came down from his chin, allowing Francis to focus on the pair of dark diagonal scabs.

“Still, seems kind of surprising in your type of building,” he said. “People in Manhattan don’t usually know their neighbors.”

“Oh, I know everybody.” The scabs stretched, revealing tiny cracks. “I grew up in that house since I was three. My father says I’m like the mayor, talking to people on the service elevator, going in and out of their kitchens with groceries. She’d only been there subletting about eight, nine months, but we got tight right away. We were both into Star Trek. …”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, I came up one night to fix her sink when she was watching ‘The Menagerie.’ You know that one? It’s the two-part episode they made out of the original pilot, ‘The Cage,’ with Jeffrey Hunter playing Captain Pike. You know, the one where the Talosians with the big lightbulb heads are keeping him behind the glass and projecting these crazy pictures into his mind, trying to get him to stay. …”

Francis nodded sagely, thinking: This is why some men never get laid.

“Not a lot of girls into science fiction, are there?”

“I don’t know. I think her older brother got her into it.”

Hoolian glanced over at the glass in the wall, gradually realizing that someone on the other side might be watching him.

They were certainly trying to project images into Francis’s mind. Telling him to speed it up, get the damn statement, wrap it up for the mayor and the PC on Live at Five. Any minute, Francis Senior Himself would be in the house, ready to put his two cents in.

“So, what time did you get done fixing her toilet?” Francis asked, paying them no mind and setting up the next part of the trap.

“’Bout ten o’clock. I remember she was watching Channel Five and they say that same thing every night. ‘It’s ten o’clock. Do you know where your children are?’”

Francis flipped back through his notes and was disappointed to see that the answer was consistent with what Hoolian had told Sully. That fucking useless civic-minded slogan must have provided about eight hundred alibis a year.

“So how long did you stay after you fixed the leak?”

“Dunno.” Hoolian pinched his shoulders. “Hour, maybe a half hour. It was hard to tell.”

“Why? Didn’t you say you had the news on?”

Don’t lunge, he warned himself. Be patient. Remember: Time is better than a kick in the balls or a phone book upside the head. Time is better than a polygraph or an eyewitness. Time can weigh on you. Time can sit on your shoulders and play with your head. Time can make you hungry and weak. Time will give you time.

“We switched to MTV and made some popcorn,” Hoolian said, faintly aware of his own words stacking up into a teetering pile. “She’d just got cable. And once those Duran Duran videos come on, one after another, man, you just sort of zone out. And then after a while, she started to get sleepy. She had to be at the hospital at eight o’clock the next morning.”

It sounded almost sweet, this pretty young doctor falling asleep in front of the TV with this horny little seventeen-year-old mooning over her.

“Did she, like, have her head on your shoulder?”

“She might have.” An earnest little nub of flesh bulged between the boy’s eyebrows. “Why do you want to know?”

“Just, you know, it’s important to get all the details right. We collect fingerprints, hair fibers. We have to figure out what belongs to who so we don’t make any mistakes and lock up the wrong people.”

The long eyelashes fanned out. “I still don’t understand.”

“Look. I have a set of facts I’m trying to make sense of. The front door of the building is locked after midnight. Okay? The only people who have keys are the tenants and the super. And your father was out that night, so you had them. The only other way to get in is to ring the front bell and wake the doorman. And that never happened. Right?”

Hoolian nodded, scratching the inside of his thigh.

“So … No sign of forced entry in Allison’s apartment. No visitors buzzed in after midnight. You’re the last person to see her that night. She doesn’t show up for work the next morning. Your father lets in the patrolman, who finds her at ten o’clock. Help me out here.”

This last part seemed to take Hoolian by surprise, like a throw from left field, a white dot out of the green getting larger and larger until it smacked him right in the mouth. “You’re not thinking my father had anything to do with it, are you?”

“No. I am not thinking that.”

They’d already checked out Osvaldo anyway. He was off on a date that night. Took a fourth-grade teacher named Susan Armenio to dinner at Victor’s Café and then cha-cha-ing at Roseland, leaving an old alkie doorman called Boodha and Hoolian running the show. Maybe that got the kid mad, Dad stepping out with his mother dead and all. Maybe he just wanted some attention. You never knew.

“Then, I don’t know what I’m supposed to say.” Hoolian fingered his scabs, mystified. “I’m thinking I should try calling my father again. He’s probably done in the basement.”

“Okay.” Francis sat up. “Of course, you can do that, but there’s something else I want to ask you about. …”

He reached into the bag at his feet, took out a red photo album. He put it down in front of Hoolian.

“You know what this is, don’t you?”

Hoolian stared at the book as if it were breathing.

“It’s Allison Wallis’s photo album. We found it in the back of your bedroom closet.”

You could almost hear the blood reversing in the kid’s veins. “My father let you look in my room?”

“He gave us permission to search your apartment this morning. He said, ‘Look everywhere.’”

Francis watched the telltale microshifting of Hoolian’s pupils.

“She let me borrow it.”

Francis sighed. “Look, Hoolian. I’m sitting here, talking to you like a man. Don’t you think we owe each other the respect of being honest? Why would you have something hidden in the back of your bedroom closet if you were just ‘borrowing it’?”

Hoolian seemed to have lost the power of human speech.

“All right.” Francis pulled back a second. “Let’s try and make it easier. You guys were friends. You liked her. You did things for her. You fixed her toilet. You hoped she would like you back.”

“No, man. It wasn’t like that. …”

“Listen.” Francis rolled his chair around to Hoolian’s side of the table: just guys talking here. “I’ve been there too. I would’ve set myself on fire for some girls when I was your age. You can’t help it. Every time she looks at you, it’s like a magnet trying to pull your heart outta your chest. You’re dying and she doesn’t even know it. Am I right?”

Hoolian hesitated, tugging on the chain inside his shirt collar.

“I’m not saying she played you on purpose, but isn’t it possible she took advantage of you just a little bit?”

“No. She was a nice person.”

“I’m not saying she wasn’t a nice person.” Francis got up and stood over him. “But even nice people take advantage sometimes. Look at it her way. You’re this eager kid coming around all the time, to fix things and keep her company. You’re a pillow for her to fall asleep on. You’re comfortable.”

Hoolian blinked, as if he’d been slapped. Oh yeah. Francis moved in on him. I got your number, son.

“Like she didn’t know how hot she was getting you.”

“It wasn’t like that.” Hoolian shook his head, eyelashes blinking a nervous semaphore. “She had a boyfriend.”

“Yeah? What was his name? Did you ever see him?”

“No …”

Francis inched forward, having spent much of the past twelve hours establishing that Allison hadn’t had a steady boyfriend since senior year at Amherst. And that guy, a Frisbee-tossing premed named Doug Wexler, was apparently down in Guatemala at the moment, running a children’s vaccination program with a couple of Maryknoll nuns.

“So, what happened?” Francis said. “You guys had a fight because she found you took her album?”

“No, she didn’t know about that,” Hoolian said too quickly, then realized what he’d just admitted. “I was going to give it back. I just wanted to see what her family looked like.”

“What’d you do, use your key to get into her apartment and take it when she wasn’t there?” Francis put a foot on his own empty seat and flexed forward like a sprinter.

“I think I better talk to a lawyer.”

From the corner of his eye, Francis saw the doorknob turn as if one of the Overlords was about to come in the room. He shook his head, asking for more time. Don’t blow it. I’m almost there. Time to go for the bomb.

“Okay, then, let me just ask you about one more thing.”

He picked up the second evidence bag and dropped it on the table in front of Hoolian. It puffed up and then collapsed in on itself more slowly than the one with the hammer in it, breathing out odorless fumes through a tiny hole. “You know what that is, don’t you?”

Hoolian shook his head, staring at the bloody little wad of cotton inside.

“You’re telling me you don’t know how Allison’s used tampon ended up in the wastepaper basket in your bathroom?”

The boy seemed to wilt with the bag.

“Somebody must have put it there,” he said weakly.

“Now how would that be?”

“I don’t know, man. I never even seen one of these before.”

Francis bore down on him. “Hoolian, come on. We have serology experts who can tell us that this is Allison’s blood on this cotton. I’m talking about irrefutable proof. …”

“But I’m telling the truth.” The boy’s lip trembled. “I’d be afraid to even touch something like that.”

“Then how the hell else would it have ended up in your bathroom? Can you tell me that?”

Hoolian gripped the arms of his chair, the Catholic boy confronted with direct evidence of his sins.

“You must have put it there,” he said.

“Me?” Francis touched his chest, bemused. “After I already had Allison’s family album in your closet and her blood on your tool? Does that make a lot of sense?”

Hoolian leaned forward in his chair a little, the eyelashes fluttering in panic.

“Look.” Francis touched the boy’s shoulder, playing Father Confessor. “Tell it to me your way. Help me understand.”

Hoolian shook his head again, clinging to threadbare denial.

“Then let me help you,” Francis said gently. “You were next to her on the couch. Maybe she let you touch her and pretended not to notice. Maybe she let you get a leg up. She had you going at ramming speed. Then all of a sudden, she decided she was too good for you. She tried to stop you dead in the water. And you can’t do that to a man, right?”

“I didn’t kill her.”

“Hoolian, I’m looking at a pair of scratches on your chin. They’re right in front of my face.”

Hoolian touched his scabs self-consciously. Just his bad luck that he had in-between skin: not golden brown like some Latinos, but not exactly pink like a white boy’s either. It was sallow and thin over the bones, almost translucent. Cuts that would heal on other kids in a day lingered on him.

“I cut myself shaving. I told the other detective that.”

“Julian, look at me. All right? The time has come to put away childish things. Remember how we talked about how we both lost our mothers?”

There was a sound in the air like water about to boil. We’re almost there. Just a little further. He’d proved the murder weapon was Hoolian’s. He’d gotten the kid to admit that he’d stolen her photo album, which showed he was obsessed. His fingerprints were all over the place, naturally. And once they matched his blood to what they’d scraped from under her fingernails, they’d probably have enough circumstantial evidence. All he needed to make it a slam-dunk and remove any possible doubt was a statement.

“So you know your mother is looking down on you right now, don’t you?”

Hoolian’s nostrils flared and contracted. The corner of his eye was glistening again. They were on the edge of something here.

“I’m telling you, man, you have to get right with what you did.”

The boy kept shaking his head. “But it’s not true.”

“Don’t keep saying that,” Francis warned him, playing this card for all he was worth. “You know she’s up there and her soul is in torment, because she’s afraid you won’t be able to join her in heaven.”

The boy opened his mouth, but only a dry creak came out.

“She didn’t raise you to be a liar, did she?”

The boy looked around for something to wipe his eyes and blow his nose with, but Francis had made a point of not bringing a box of Kleenex into the room.

“That shit is going to eat you inside. You know you’ve got to ask for forgiveness.”

Hoolian bit his lip and shook his head again, more furiously this time.

Come on. You want to tell me. Everybody wants to confess.

“You gotta do it, brother.” Francis loomed over him. “You have to get right with this. I’m giving you a way out. I know you’re a good boy.”

Yes, I’m your friend. Who else would be trying to put you in prison the rest of your life?

Hoolian took a deep breath, folded his hands on his lap, and stared at them, a small pale cathedral of fingers.

“All I’m asking you to do is to stand up to what you did. All I’m asking you to do is be a man.”

The joints squeezed tighter, the little cathedral showing veins in the marble.

Francis crossed his arms, finding himself knotting up as well. Because what the Overlords behind the glass had forgotten was: it wasn’t all bullshit and play-acting. Sure, you could get all righteous about it afterward, grandstanding for the press and pointing the finger at “the defendant” in court, saying, “We the People condemn you and cast you out. Begone from the sight of all good free men and women.” But sometimes, in this quiet little room, before the lawyers and stenographers came in, there was a half-second when you were almost on the guy’s side. Not above him or on the sidelines passing judgment. But right there in the thick of it with him, step-by-step, on his level, seeing it through his eyes. And, in your mind at least, doing the same things that he’d done. Because otherwise, why would anyone trust you enough to tell you the worst thing he ever did? You could never explain it to the so-called decent, normal, law-abiding civilians. To get someone to give it up, to lay himself before you, you had to put some soul into it, some compassion, you had to feel for him—if only for that instant right before he confessed. And then, of course, you could safely turn around on him and use his desperate little plea to be understood to ruin his life.

“So, what do you say?” he asked, ready to reach for a pen. “Are you gonna be a man or not?”

The kid looked up, as if he realized he’d just reached his own childhood’s end.

“You said I could talk to my father.”

10

IT’S TEN O’CLOCK. DO you know where your children are?”

Just as the local news was starting, the former Miss Patti D’Angelo of Brooklyn walked into the living room of her Carroll Gardens row house and found her husband, Francis X., sprawled in the BarcaLounger with an ice pack on his knee.

“What happened to you?”

“Goddamn coffee table,” he grumbled. “Banged myself on it, going for the phone before.”

“Who was calling?”

“Nobody. I picked it up and there was just dead air.”

“Hmm. Maybe one of your old girlfriends stalking you.”

She eyed the ice pack and perched on the arm of his chair. Probably thinking he’d fallen off the wagon, the way he kept knocking into things lately. He knew he’d have to set her straight eventually, but every time he tried to imagine The Conversation his mind stalled out.

She’d be compassionate. She’d be concerned. She’d go to the library and do research on the Internet. She’d get on all the listservs. She’d start making phone calls about getting him into the appropriate programs and clinics for people with his condition. She’d find out what the best kind of cane was and where support groups met. And he’d hate it. Because it would be the beginning of pity.

“So how was your day?” she asked, massaging the knotted muscles in the back of his neck.

“Complicated.”

“Oh?”

He felt guilty, naturally. They’d been trying to talk more lately. Neither of them wanted to have one of those traditional “don’t ask, don’t tell” cop marriages anymore, where they never got into what he did all day. She’d been in the game a little herself, five years as a prosecutor, so she didn’t necessarily freak out if he happened to mention something about blood spatter, stippling, or septicemia. Twenty-two years they’d been together, two kids, over the river and through the woods, down into the Valley of Shadows and out into the sun again, sometimes even for vacations in Cancún. And here he was, sitting too close to the TV screen, a lump the size of a Ping-Pong ball throbbing on his knee, not telling her about the most important thing that had happened to them since the kids were born.

“Fuckin’ old case, coming up again,” he said. “They let Julian Vega out early.”

“Seriously?”

“Here. What’m I, lying?”

He used the remote to turn up the volume. Roseanna Scotto throwing it over live with a swooshing noise to Lisa Evers standing across the street from 1347 Lexington.

“Roseanna, they say everything old is new again, and here on the Upper East Side, memories of a notorious murder case are being revived. …”

“It’s ridiculous,” Francis said, talking over her. “They overturned the conviction because his lawyer didn’t tell him he had the right to testify. Like that’s anybody else’s problem.”

“So you’re upset.”

“Damn straight. I put a lot of work into that case.”

There was a quick cut and Debbie Aaron’s face filled the screen, drawn and severe against a background of tilting law books on a sagging shelf.

“This is a classic example of the police abusing their authority,” she was saying. “The detectives in charge of this investigation settled on my client as a suspect before they investigated any other leads. …”

“See? That’s what pisses me off.” Francis waved his hand, glad to have somewhere else to direct all this agita. “She knows she doesn’t have a real case, so she’s just running her mouth. …”

“She looks good, Deb.” Patti straightened her back. “I don’t think she’s had any work done.”

“You look better.”

“Hmmp.” She ran her fingers through her highlights and gave him a four-beat stare.

“They made the facts fit the case against him,” Deb was telling the camera.

“Bullshit,” said Francis.

“You know, she can’t hear you.” Patti squeezed the back of his neck.

“And a number of highly irregular things happened in this investigation that need to be looked into,” Deb said just as the screen switched to file footage from twenty years ago. “There’s been a gross miscarriage of justice.”

Francis watched the doors of the 19th Precinct swing open and saw himself at twenty-nine again, perp-walking Hoolian past the assembled cameras and microphones.

It looked so different from this angle. At the time, it was this unambiguous moment of triumph: Coming out of a grueling marathon in the box with an incriminating statement. Making up for his stint on the Farm by breaking the biggest case of the year. The Old Man himself, years from the grip of Alzheimer’s, trundling along behind him, shooting the Turk an “I told ya so” grin. So why do I look like I’m the fucking skell? Francis asked himself. I did all right. I went over the wall and made it back in one piece. I did my job. I made someone pay. But there he was on the screen, tie askew, shirttail coming out, dog-faced and disheveled, as if he were the one with something to hide. Hadn’t he watched this exact same footage twenty years ago, on a smaller Sony screen, with Patti four months pregnant and Francis Jr. still sleeping in the crib? And hadn’t she leaned over, kissed him, and told him how proud she was?

And then here was Hoolian again, with his hands cuffed behind his back and his St. Crispin’s blazer bunched up around his shoulders. In his mind’s eye, Francis remembered the kid flashing a ferrety little smirk, as if he were sure he was going to beat this case somehow. But watching it now, Francis saw the little wispy mustache jerk up, revealing a pair of oversize front teeth, and he realized the boy had just been scared.

“He was so young,” said Patti. “I forgot that.”

“Didn’t stop him from staving that poor girl’s face in.”

“I’m just saying it’s surprising. He looks so sweet.”

He caressed her thigh. Unlike Debbie A. and Paul Raedo, Patti wasn’t a good hater. Never had the talent for it like other prosecutors. Because at heart, she was a nice person, a former fat girl who just wanted people to like her. Instead of riding out to grisly triple homicides on East 125th Street at four in the morning, she’d spent most of these past two decades mastering the art of forgiveness, immersing herself in child rearing, nurturing friendships, healthy diets, home improvements, and eventually a happening little career for herself as a personal trainer for corporate CEOs in Manhattan. In short, living what normal people called a life.

On the screen, there was a cut to Paul Raedo, his bristly scalp flexing in earnest concern, giving the official line from the DA’s office. “Our only comment right now is that the original jury made their decision based on the evidence and we feel confident that will be borne out.”

“So are they going to dismiss the indictment?” Patti spoke over him, never having been much of a Raedo aficionado.

“Fuck no. He got twenty-five to life. He should do the whole bid.”

“What are you, the Ayatollah Khomeini?” She drew back. “You got twenty years out of this kid. Isn’t that enough?”

“Hey, I didn’t come up with that sentence. The judge and jury looked at the same facts I did. I’m just making sure no one forgets who the victim was here.”

“So, what, you’re going to try the whole case all over again?”

“Well …”

He was distracted, seeing Debbie A. given the last word. “The tragedy is a young man lost his freedom for something he didn’t do.”

He lowered the volume with the remote. “What am I supposed to do? Stand there, smiling, while somebody calls me a lying sack of shit?”

“What do you care? I thought you were retiring as soon as you got the bump to First Grade in April.”

He hesitated, not wanting to bring up the whole ugly threat of liability that Paul raised this morning. “I just want to make sure I don’t leave any loose ends lying around.”

“Why? You going off somewhere without telling me?”

“Nah, I just …” He started to rub his eyes and then stopped himself. “Forget about it, Patti. All right? Just never mind.”

She got up. “If you’re working this case again, I hope I’m not going to have to cancel Thanksgiving in Florida. I already put a security deposit on the condo, and Kayleigh is coming down from Smith with a friend.”

“I’m sure it’ll be done by then.”

She started out of the room. “Frankie called on the satellite phone before you came home.”

“Yeah?” He twisted around. “How’s he doing?”

“Tells me everything except what I need to know. Just like his father. Far as I can tell, though, no one’s talking about sending him over yet.”

“Fucking kid’ll be the death of me. I hope he’s satisfied.”

“I’m going to bed,” she sighed, not up for the argument. “Maybe I’ll see you there. I’ll be the one in the flimsy nightgown.”

“Yeah, I’ll be up in a little while.”

He watched her go and changed the position of the ice pack on his knee.

So here we are. He picked up the remote and switched to the Yankees game. Mariano Rivera mopping up against the Red Sox, another old rivalry coming around again. The Curse of the Bambino. He watched for half an inning and found he couldn’t concentrate from one pitch to the next. He changed the channel and found himself watching Iraq coverage on Fox News Live. “America at War” and the flag, in the lower right-hand corner. Tanks in the streets of Baghdad, another convoy attacked in the desert, and still no weapons of mass destruction. And this is where they want to send my son.

Not much to put a troubled mind at ease there. He switched to Star Trek for a while. Captain Kirk strutting around with his stomach hanging out on that same Styrofoam planet, romancing green-skinned women in the days before he started playing a cop on T. J. Hooker. “The Cage.” Wasn’t that the show he’d talked about with Hoolian, way back when? Except the kid said it was Jeffrey Hunter playing the captain of the Enterprise. Wasn’t that the same guy from The Searchers helping John Wayne track down the girl who’d been kidnapped by the Indians?

All right, now you’ve strayed a little too far off the reservation yourself, Loughlin. He turned off the set and sat there, contemplating the silence.

His eyes roamed toward the bookshelves he’d built a couple of years ago, scanning the unbroken spines of volumes he’d been collecting for all that leisure reading he was going to do after he retired. Now it dawned on him that one day in the not-too-distant future he’d have to decide which of them would be the last book he’d ever read. He looked for a likely candidate. Shelby Foote on Gettysburg. Stephen Ambrose on D-Day. Or his new main man, Ernest Shackleton on the Endurance. Stubborn bastard after his own heart. Tried to lead a crew to Antarctica and wound up with a ship crushed to matchsticks in the ice. That was some ballsy call he made, jumping in a lifeboat with five other guys, to try and get help over eight hundred miles of glaciers and hurricane-swept waters. To Francis, the miracle wasn’t just that he managed to save every man but that he somehow made it across all that blank space without losing his mind.

Jesus, he could use a drink here.

He listened to the ticking of the kitchen clock. His thoughts breaking apart and rearranging themselves. He should turn in his papers tomorrow. He should keep acting like nothing was wrong. He should see another doctor and get a second opinion. The ticking became the tapping of a cane on pavement. Some day crossing Union Street would be as hard as crossing Antarctica. Except instead of dying trying to reach the South Pole, he’d probably just get hit by a car like his mother on the Grand Concourse.

Now there’s a happy thought!

Where did he see that half-empty vodka bottle the other day anyway? Wasn’t it gathering dust somewhere near the boiler in the basement, waiting to be thrown out? He didn’t need to get a buzz on. Just a couple of fingers in the old Grateful Dead mug, to take the edge off a little.

Nah, don’t be such a fucking morose self-pitying bastard, Francis. The old man went that way and look where it got him. He’d done better than that, hadn’t he? At least for most of the past twenty years he had. Laying off the drink, devoting himself to the family, above reproach on the Job, the kind of cop you’d want handling the case if your best friend got killed. So why were his eyes turning into a couple of useless orbs? Was this payback for something specific or just the general taint of Original Sin?

He’d always had a kind of rough give-and-take with the Higher Authority, more or less getting walloped every time he lapsed. After his mother died, he figured it must have been his fault somehow, maybe because he hadn’t prayed enough when she’d asked him to, so he’d tried to do penance. Five years as an altar boy kept the rest of the family in good health, he figured. But then he’d backslid in tenth grade, deciding it was all a bunch of shit, so he might as well become a dope-smoking moron. Until a car accident on the Major Deegan left his sister in a neck brace and put the fear of God back into him.

Not that he’d ever been a full-time nut about keeping a running account. Just every once in a while something would happen to whip him back into line. He’d begin running around on Patti a little just after they got married and then wind up nearly taking a bullet in the head on a narcotics raid. Or he’d start drinking again and Kayleigh would end up in the neonatal intensive care unit with a kidney infection.

But time goes by, nothing goes wrong, and you think you must be in the clear. Until your son joins the army without telling you and your retinas start deteriorating.

He squeezed the arms of his chair and started to get up, the clock on the kitchen stove still ticking loudly. Closure.