APPENDIX I:

HOW MANY TETRAKTYS ARE THERE?

BY THEON OF SMYRNA

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE QUATERNARY obtained by addition (that is to say 1 + 2 + 3 + 4) is great in music because all the consonances are found in it. But it is not only for this reason that all Pythagoreans hold it in highest esteem: it is also because it seems to outline the entire nature of the universe. It is for this reason that the formula of their oath was: “I swear by the one who has bestowed the Tetraktys to the coming generations, source of eternal nature, into our souls.” The one who bestowed it was Pythagoras, and it has been said that the Tetraktys appears indeed to have been discovered by him.

The first quaternary is the one of which we've just spoken: it is formed by addition of the first four numbers.

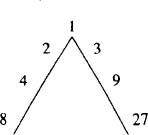

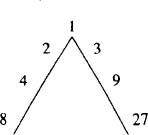

The second is formed by multiplication, of even and odd numbers, starting from unity. Of these numbers, unity is the first because, as we have said, it is the principle of all the even numbers, the odd numbers and of all the odd-even numbers, and its essence is simple. Next comes three numbers from the odd as well as the even series. They allow for the unification of odd and even because numbers are not only odd or even. For this reason, in multiplication, two quaternaries are taken, one even, the other odd; the even in double ratio, the first of the even numbers being 2 which comes from unity doubled; the odd in triple ratio, the first of the odd numbers being the number 3 which arise from unity being tripled, so that unity is odd and even simultaneously and belongs to both. The second number in the even and double [series] is 2 and in the odd and triple is 3. The third of the order of even numbers is 4, and in the odd series, 9. The fourth among the even numbers is 8, and among the odd numbers, 27.

FIGURE 17. THE PLATONIC LAMBDA

The ratios of the most perfect consonances are found in these numbers; even the tone is included. However unity contains the principle of ratio, of limit and of point. The second numbers, 2 and 3, have the side ratio, being prime, incomposite numbers, and measured only by the unit, and are consequently linear numbers. The third terms, 4 and 9, have the power of the squared surface, being equally equal (that is to say square numbers). The fourth terms, 8 and 27, have the power of the cubic solid, being equally equal equally (that is to say, cubic numbers). In this way, by virtue of the numbers from this tetraktys, growth proceeds from the limit and the point up to the solid. In fact, after the limit and the point comes the side, then the surface and finally the solid. It is with these numbers that Plato, in the Timaeus, constitutes the [world] soul.* The last of these seven numbers is equal to the sum of all the preceding, as we have 1+2+3+4+8+9=27.

There are then two quaternaries of numbers, one which is made by addition, the other by multiplication; and these quaternaries encompass the musical, geometric and arithmetic ratios of which the harmony of the universe is composed.

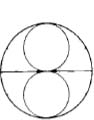

The third quaternary is that which, following the same proportion, embraces the nature of all magnitudes, for the place taken by unity, in the preceding quaternary, is that of the point in this one; and that of the numbers 2 and 3, having lateral (or linear) power, is here that of the line, through its double form, straight or circular, the straight line corresponding to the even number because it terminates at two points (the line and circle are given as examples here), and the circular to the odd, because it is composed of a single line without terminus.

And what, in the preceding quaternary, are the numbers 4 and 9, having the power of the surface, the two types of surface, the planar and the curved, are so (surface) in this one. Finally, what, in the preceding are the numbers 8 and 27, which have the power of the cube and of which one is even and the other odd, is constituted by the solid in this one. There are two kinds of solids, one with a curved surface, like the sphere or the cylinder, the other with a plane surface, such as the cube and the pyramid. This is the third tetraktys then, the one having the property of constituting any magnitude, through the point, the line, the surface and the solid.

The fourth quaternary is that of the simple bodies, fire, air, water and earth, and it offers the same proportion as the quaternary of numbers. The place occupied by unity in the quaternary of numbers is taken by fire in this one, air corresponds to the number 2, water to the number 3, earth to the number 4; such is indeed the nature of the elements according to their fineness or density, in such a way that fire is to air as 1 is to 2, to water as 1 is to 3, and to earth as 1 is to 4. The other relationships are also equal (that is to say, that air is to water as 2 is to 3, and so forth for the others).

The fifth quaternary is that of the shapes of simple bodies, for the pyramid is the figure of fire, the octahedron the figure of air, the icosahedron the figure of water and the cube the figure of earth.

The sixth is that of the created things, the seed being analogous to unity and the point. A growth in length is analogous to the number 2 and the line, and a growth in width is analogous to the number 3 and to the surface, and finally a growth in thickness is analogous to the number 4 and to the solid.

The seventh quaternary is that of societies. Man is principle and is thus unity. The family corresponds to the number 2, the village to the number 3 and the city to the number 4; for these are the elements which comprise the nation.

All of these quaternaries are material and perceptible.

The eighth contains faculties by which we are able to form judgment on the preceding, and which are its intellectual part, namely: thought, science, opinion and feeling. And certainly thought, in its essence, must be assimilated to unity; science is the number 2, because it is the science of all things; opinion is like the number 3, because it is something between science and ignorance; and finally feeling is like the number 4 because it is quadruple, the sense of touch being common to all, all the senses being motivated through contact.

The ninth quaternary is that which composes the living things, body and soul, the soul having three parts, the rational, the emotional and the willful; the fourth part is the body in which the soul resides.

The tenth quaternary is that of the of the seasons of the year, through the succession of which all things take birth, that is, spring, summer, autumn and winter.

The eleventh is that of the ages: childhood, adolescence, maturity and old age.

There are thus eleven quaternaries. The first is that of the numbers which are formed by addition, the second is that of the numbers formed by multiplication, the fourth is that of magnitudes, the fifth is that of simple bodies, the sixth is that of created things, the seventh is that of societies, the eighth is that of the faculties of judgment, the ninth is that of the living things, the tenth is that of the seasons, and the eleventh is that of the ages. They are proportional to one another, since what is unity in the first and the second quaternary, the point is in the third, fire is in fourth, the pyramid in the fifth, the seed in the sixth, man in the seventh, thought in the eighth, and so forth with the others following the same proportion.

Thus the first quaternary is 1, 2, 3, 4. The second is unity, the side, the square, the cube. The third is the point, the line, the surface, the solid. The fourth is fire, air, water, earth. The fifth is the pyramid, the octahedron, the icosahedron, the cube. The sixth is the seed, the length, the width, the height. The seventh is man, the family, the village, the city. The eighth is thought, science, opinion, sense. The ninth is the rational, the emotional and the willful parts of the soul, and the body. The tenth is spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The eleventh is childhood, adolescence, maturity and old age. And the perfect world which results from these quaternaries is geometrically, harmonically and arithmetically arranged, containing in power the entire nature of number, every magnitude and every body, whether simple or composite. It is perfect because everything is part of it, and it is itself a part of nothing else. This is why the Pythagoreans used the oath whose formula we have reported, and through which all things are assimilated to number.

From Theon of Smyrna: Mathematics Useful for Understanding Plato, Chapter 38. Translated by Robert and Deborah Lawlor. San Diego, Wizards Bookshelf, 1979. Reproduced with permission of the publisher.

* Plato, Timaeus 36BC.

APPENDIX II:

THE PYTHAGOREAN TITLES

OF THE FIRST TEN NUMBERS

FROM THE THEOLOGY OF NUMBERS BY IAMBLICHUS

TRANSLATED BY DAVID R. FIDELER

PLUTARCH AND PLOTINUS inform us that the Pythagoreans called the One Apollo because of its lack of multiplicity—this is both a clever pun and a revealing statement, for a-pollon in Greek means literally “not of many.”

Such, then, was the Greek style of “theological arithmetic.” This form of number symbolism became quite popular in late antiquity and much of it was transmitted by Christian writers through Medieval times. The symbolism finds its basis in the Pythagorean observation that the primary numbers represent far more than quantitative signs: each one of the primary numbers is a qualitative, archetypal essence, possessing a distinct, living personality. This personality can be directly intuited by studying the archetypal manifestations of these principles in the realms arithmetic (number in itself), geometry (number in space) and harmonics (number in time).

The following list represents a compilation of the titles from the anonymous Theology of Arithmetic which was based closely on a work by lamblichus. Since the first printing of this volume, however, a complete, fully annotated translation of The Theology of Arithmetic has appeared, which represents the first translation of this work into any European language (The Theology of Arithmetic, translated by Robin Waterfield, Phanes Press, Grand Rapids, 1988.) In the text, explanations are given for the various appellations. For more on arithmology also see book three of Thomas Taylor's Theoretic Arithmetic of the Pythagoreans and the section on number symbolism in Thomas Stanley's Pythagoras.

THE MONAD

Instrument of Truth

Obscure

Not-Many

A Chariot

Male-Female

Immutable Truth and Invulnerable Destiny

A Seed

Fabricator (demiurge)

True Happiness (eudaimonia)

Zeus

Life

God

The Equality in Increase and Decrease

Memory

A Ship

Essence (ousia)

The Inkeeper (pandokeus), “that which takes in all”

The Pattern or Model (paradeigma)

The Moulder

Prometheus

The First (Proteus)

Darkness

Blending

Commixture

Harmony (symphonia)

Order (taxis)

Materia

A Friend

Infinite Expanse (chaos)

Space-Producer

THE DYAD

Inequality

Indefinite (aoristos)

The Unlimited (apeiron)

Without Form or Figure

Growth

Birth

Judgment

Appearance

Anguish

The Each of Two

Falling Short, Defect

Erato

Equal

Isis

Movement

The Ratio (logos) in Proportion (analogia)

Revolution

Distance

Impulse

Excess

The Thing with Another

Rhea (the wife of Kronos, but also “flow”)

Selene

Combination

That Which is To Be Endured; Misery, Distress

Boldness, Audacity (tolma)

Matter

Obstinacy

Nature

THE TRIAD

Proportion (analogia)

Harmonia

Marriage

Knowledge (gnosis)

Peace

Every Thing

Hecate

Good Counsel

Piety

The Mean Between Two Extremes

Oneness of Mind

The All

Perfection

Friendship

Purpose

THE TETRAD

Nature of Change

Righteousness

Hercules

Holding the Key of Nature

THE PENTAD

Alteration

Immortal

Androgyny

Lack of Strife

Aphrodite

Boubastia (named after the Egyptian divinity Boubastis)

Wedding

Marriage

Double

Manifesting Justice

Justice

Demigod

Nemesis

Pallas

Five-Fold

Forethought

Light

THE HEXAD

Resembling Justice

The Thunder-Stone

Amphitrite (Poseidon's wife; a verbal pun: on both sides [amphis] three [trias])

Male-Female

Marriage

Finest of All

In Two Measures

Form of Forms

Peace

Far-Shooting (name of Apollo)

Thaleia

Kosmos

Possessing Wholeness

Cure-Ail (panacea)

Perfection

Three-Fold

Health

Reconciling

THE HEPTAD

The Forager (epithet of Athena)

Athena

Citadel (akropolis)

Reaper

Hard to Subdue Defence

Due Measure (kairos)

Virgin (parthenos)

Revered Seven (septas + sebomai = heptas)

Bringing to Completion (Telesphorus)

Fortune, Fate

Preserving

THE OCTAD

Untimely Born

Steadfast

Seat or Abode

Euterpe

Cadmia

Mother

All Harmonious

THE ENNEAD

Brother and Consort of Zeus

Helios

Absence of Strife

Far-Working (epithet of Apollo)

Hera

Hephaestus

Maiden (kore)

Of the Kouretes

Assimilation

Oneness of Mind

Horizon (because it limits the series of Memory units before returning to the Decad)

Crossing or Passage

Prometheus

Consort and Brother

Perfection

Bringing to Perfection (Telesphorus)

Terpsichore

Hyperion

Oceanus

THE DECAD

Eternity (aeon)

Untiring

Necessity

Atlas

Fate

Helios

God

Key-Holding

Kosmos

Strength

Memory

Ourania

Heaven

All

All Perfect

Faith

Phanes

APPENDIX III:

THE FORMATION AND RATIOS

OF THE PYTHAGOREAN SCALE

BY DAVID R. FIDELER

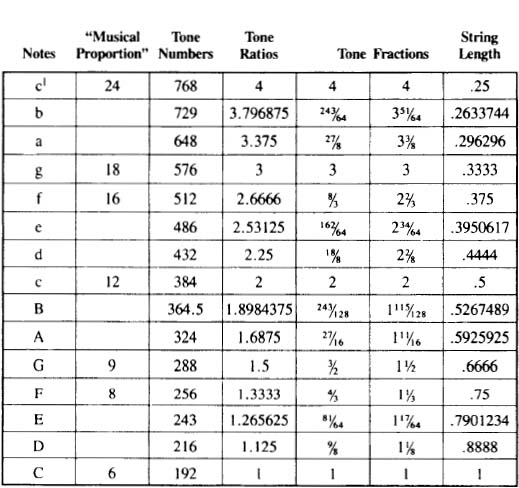

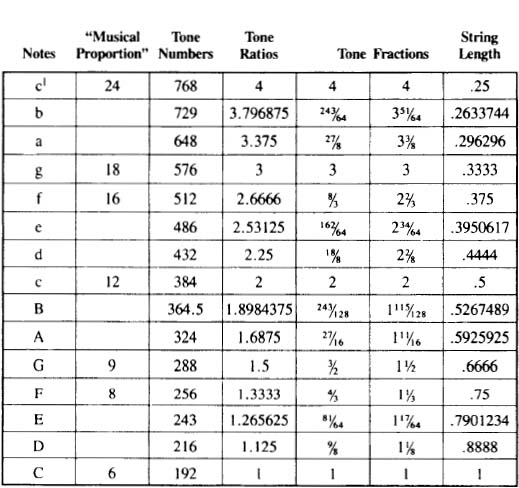

FIGURE 19. THE RATIOS OF THE PYTHAGOREAN SCALE

AS NOTED in the introductory essay, the structure of the musical scale possesses a great deal of significance in Pythagorean thought as it is an excellent example of the principle of mathematical harmonia at work. In the case of the scale, the “opposites” of the high (2) and the low (1)—the two extremes of the octaveare united in one continuum of tonal relationships through the use of a variety of forms of proportion which actively mediate between these two extremes.

The best way to understand the mathematical principles of harmonic mediation involves actually charting out and playing out the ratios of the scale on the monochord. In constructing a monochord, it is best to make it as long as possible, perhaps in the region of 4—5 feet, as that makes it easier to differentiate between the harmonic nodal points at the high end of the spectrum (see fig. 6).

It is useful at first to play out the harmonic overtone series. Measure the exact length of the string and then mark off the overtone intervals: ½ the string length,  the string length, ¼ the string length, etc. It is possible to play out the overtone series without the use of the bridge; simply pluck the string about 1 inch from either end while simultaneously touching the nodal point with the other hand. It will be noted that there is an inverse relationship between the vibrational frequency of the tone and the string length. This is also illustrated in the above chart: hence a tone with a vibration of 2 is associated with a string division of .5 or ½ It is also useful at this point to play out the harmonic “Tetraktys,” or the perfect consonances: 1:2 (octave), 2:3 (perfect fifth), and 3:4 (perfect fourth). Listen carefully to these ratios and reflect on the fact that you are actually hearing the relationships between these primary whole numbers.

the string length, ¼ the string length, etc. It is possible to play out the overtone series without the use of the bridge; simply pluck the string about 1 inch from either end while simultaneously touching the nodal point with the other hand. It will be noted that there is an inverse relationship between the vibrational frequency of the tone and the string length. This is also illustrated in the above chart: hence a tone with a vibration of 2 is associated with a string division of .5 or ½ It is also useful at this point to play out the harmonic “Tetraktys,” or the perfect consonances: 1:2 (octave), 2:3 (perfect fifth), and 3:4 (perfect fourth). Listen carefully to these ratios and reflect on the fact that you are actually hearing the relationships between these primary whole numbers.

To “tune” the monochord to the ratios of the Pythagorean scale use the string length ratios in the above chart, multiplying these ratios by the length of the string. Mark off these intervals, along with the corresponding notes, on the sounding board as they are carefully measured out.

Having marked out the Pythagorean scale, it might be useful at this point to review the material in the introductory essay relating to the harmonic proportion and then to play out these relations:

1) Play out the relationship of the octave (1:2). These are the two tonal extremes which must be united.

2) Play out the arithmetic mean linking together the extremes: C—G—c, or 6—9—12. This is the perfect fifth, the strongest musical relationship (2:3).

3) Play out the harmonic mean linking together the two extremes: C—F—c, or 6—8—12. This is the perfect fourth, the next strongest musical relationship (3:4).

4) Now play out the harmonic or musical proportion which is the basis of the musical scale: C—F—G—c, or 6:8::9::12. Play this out as a continued proportion and then the individual parts. Play out the two perfect fifths 6:9 and 8:12. Play out the two perfect fourths 6:8 and 9:12. Then play out the whole tone 8:9.

5) Having played out the harmonic foundation of the scale, now “fill in” the remaining 8:9 whole tone intervals. Play out C—D, D—E, G—A, and A—B. Along with F—G, these are all in the 8:9 ratio.

6) Play out the ratio of the leimma or the semitone: E—F and B—c. The leimma is the relationship between the perfect fourth and three whole tones.

7) Finally play out the entire scale: C—D—E—F—G—A—B—c. Through the use of arithmetic, harmonic and geometric proportion the two extremes have been successfully united.

APPENDIX IV.

A SUMMARY OF PYTHAGOREAN

MATHEMATICAL DISCOVERIES

BY SIR THOMAS HEATH

NOT ONLY did the early Pythagoreans make many contributions in the realm of philosophy, but their mathematical studies laid the foundation for the development of Greek geometry, and many portions of Euclid's Elements can be traced back to mathematical discoveries of the Pythagorean school.

This listing of early Pythagorean mathematical discoveries is excerpted from Thomas Heath's History of Greek Mathematics, vol. I, pp. 166-169.

A SUMMARY OF PYTHAGOREAN MATHEMATICAL

DISCOVERIES

1. They were acquainted with the properties of parallel lines, which they used for the purpose of establishing by a general proof the proposition that the sum of the three angles of any triangle is equal to two right angles. This latter proposition they again used to establish the well-known theorems about the sums of the exterior and interior angles, respectively, of any polygon.

2. They originated the subject of equivalent areas, the transformation of an area of one form into another of different form and, in particular, the whole method of application of areas, constituting a geometrical algebra, whereby they effect the equivalent of the algebraical processes of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, squaring, extraction of the square root, and finally the complete solution to the mixed quadratic equation x2±pxq = 0 so far as its roots are real. Expressed in terms of Euclid, this means the whole content of Book I. 35-48 and Book II. The method of application of areas is one of the most fundamental in the whole of later Greek geometry; it takes its place by the side of the powerful method of proportion; moreover, it is the starting point of Apollonius' theory of conics, and the three fundamental terms, parabole, ellipsis, and hyperbole used to describe the three separate problems in ‘application' were actually employed by Apollonius to denote the three conics, names which, of course, are those which we use to-day. Nor was the use of the geometrical algebra for solving numerical problems unknown to the Pythagoreans; this is proved by the fact that the theorems of Eucl. II. 9, 10 were invented for the purpose of finding successive integral solutions of the indeterminate equations

3. They had a theory of proportion pretty fully developed. We know nothing of the form in which it was expounded; all we know is that it took no account of incommensurable magnitudes. Hence we conclude that it was a numerical theory, a theory on the same lines as that contained in Book VII of Euclid's Elements.

They were aware of the properties of similar figures. This is clear from the fact that they must be assumed to have solved the problem, which was, according to Plutarch, attributed to Pythagoras himself, of describing a figure which shall be similar to one given figure and equal in area to another given figure. This implies a knowledge of the proposition that similar figures (triangles or polygons) are to one another in the duplicate ratio of corresponding sides (Eucl. VI. 19, 20). As the problem is solved in Eucl. VI. 25, we assume that, subject to the qualification that their theorems about similarity, &c., were only established of figures in which corresponding elements are commensurable, they had theorems corresponding to a great part of Eucl., Book VI.

Again, they knew how to cut a straight line in extreme and mean ratio (Eucl. VI. 30);* this problem was presumably solved by the method used in Eucl. II. 11, rather than by that of Eucl. VI. 30, which depends on the solution of a problem in the application of areas more general than the methods of Book II enable us to solve, the problem namely of Eucl. VI. 29.

4. They had discovered, or were aware of the existence of, the five regular solids. These they may have constructed empirically by putting together squares, equilateral triangles, and pentagons. This implies that they could construct a regular pentagon and, as this construction depends upon the construction of an isosceles triangle in which each of the base angles is double of the vertical angle, and this again on the cutting of a line in extreme and mean ratio, we may fairly assume that this was the way in which the construction of the regular pentagon was actually evolved. It would follow that the solution of problems by analysis was already practised by the Pythagoreans, notwithstanding that the discovery of the analytical method is attributed by Proclus to Plato. As the particular construction is practically given in Eucl. IV. 10, 11, we may assume that the content of Eucl. IV was also partly Pythagorean.

5. They discovered the existence of the irrational in the sense that they proved the incommensurability of the diagonal of a square with reference to its side; in other words, they proved the irrationality of \fl. As a proof of this is referred to by Aristotle in terms which correspond to the method used in a proposition interpolated in Euclid, Book X, we may conclude that this proof is ancient, and therefore that it was probably the proof used by the discoverers of the proposition. The method is to prove that, if the diagonal of a square is commensurable with the side, then the same number must be both odd and even; here then we probably have of early Pythagorean use of the method of reductio ad absurdum.

Not only did the Pythagoreans discover the irrationality of \f 2; they showed, as we have seen, how to approximate as closely as we please to its numerical value.

After the discovery of this one case of irrationality, it would be obvious that propositions theretofore proven by means of the numerical theory of proportion, which was inapplicable to incommensurable magnitudes, were only partially proved. Accordingly, pending the discovery of a theory of proportion applicable to incommensurable as well as commensurable magnitudes, there would be an inducement to substitute, where possible, for proofs employing the theory of proportion other proofs independent of that theory. This substitution is carried rather far in Euclid, Books I-IV; it does not follow that the Pythagoreans remodelled their proofs to the same extent as Euclid felt bound to do.

*The extreme and mean division of the line is an important mathematical and geometrical ratio which underlies various universal fonns. This is the so-called “Divine Proportion,” “Golden Section,” or Phi ratio. On the properties and signifllCance of this principle see Ghyka, The Geometry of Art and Life, and other titles on sacred geometry listed in the bibliography.

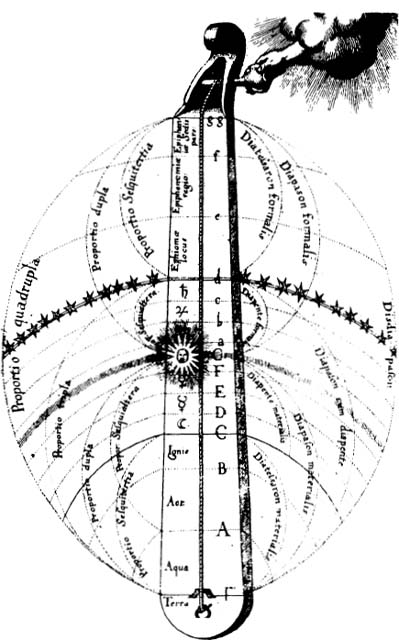

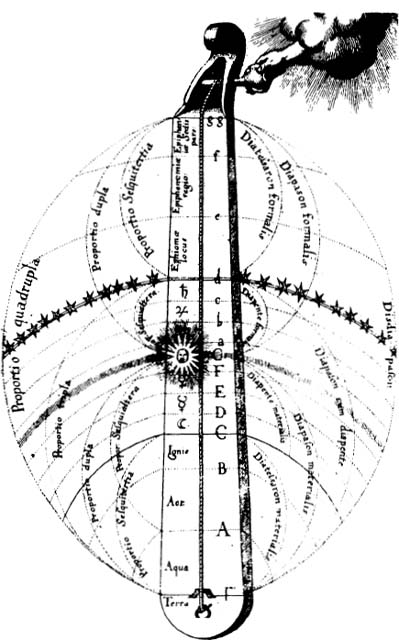

FIGURE 18. THE DIVINE MONOCHORD. This particular monochord is tuned in the key of G. while the examples on the right and in the introduction use the key of C. The three top notes on this monochord are incorrectly placed.

the string length, ¼ the string length, etc. It is possible to play out the overtone series without the use of the bridge; simply pluck the string about 1 inch from either end while simultaneously touching the nodal point with the other hand. It will be noted that there is an inverse relationship between the vibrational frequency of the tone and the string length. This is also illustrated in the above chart: hence a tone with a vibration of 2 is associated with a string division of .5 or ½ It is also useful at this point to play out the harmonic “Tetraktys,” or the perfect consonances: 1:2 (octave), 2:3 (perfect fifth), and 3:4 (perfect fourth). Listen carefully to these ratios and reflect on the fact that you are actually hearing the relationships between these primary whole numbers.

the string length, ¼ the string length, etc. It is possible to play out the overtone series without the use of the bridge; simply pluck the string about 1 inch from either end while simultaneously touching the nodal point with the other hand. It will be noted that there is an inverse relationship between the vibrational frequency of the tone and the string length. This is also illustrated in the above chart: hence a tone with a vibration of 2 is associated with a string division of .5 or ½ It is also useful at this point to play out the harmonic “Tetraktys,” or the perfect consonances: 1:2 (octave), 2:3 (perfect fifth), and 3:4 (perfect fourth). Listen carefully to these ratios and reflect on the fact that you are actually hearing the relationships between these primary whole numbers.