Bibliography

Devold, Simon Flemm. Morten 11 jaar. Zeist, Holland: Indigo, 1997. [Conversations about life with a child who is going to die.]

Dossey, Larry. Recovering the Soul: A Scientific and Spiritual Search. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1989. [The connection between mysticism, religion, physics, and the healing arts.]

———. Space, Time & Medicine. Boston: Shambhala, 1982.

Duff, Kat. The Alchemy of Illness. New York: Crown Publishing Group, 1994.

Epstein, Alan. Understanding Aspects: The Inconjunct. Reno, NV: Trines Publishing, 1997.

Franz, Marie-Louise von, and J. Hillman. Lectures on Jung's Typology. Zürich: Spring Publications, 1971.

———. Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. Boston: Shambhala, 1995.

Furth, Gregg M. The Secret World of Drawings: Healing through Art. Gloucester, MA: Sigo Press, 1989.

Greene, Liz. The Art of Stealing Fire: Uranus in the Horoscope. London: Centre for Psychological Astrology Press, 1996.

Hamaker-Zondag, Karen. Aspects and Personality. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1990.

———. Foundations of Personality. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1994.

———. House Connection. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1994.

———. Psychological Astrology. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1990.

———. The Twelfth House. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1992.

Hand, Robert. Planets in Composite: Analyzing Human Relationships. Atglen, PA: Whitford Press, 1975.

Jacobi, Jolande. The Psychology of C. G. Jung. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1973. [An introduction to his work.]

Jung, C. G. Answer to Job. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

———. The Collected Works. 20 volumes. Bollingen Series XX. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953–1979; and London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953–1979.

———. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Aniela Jaffe, editor; Richard and Clara Winston, trans. New York: Pantheon, 1961; New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

———. Man and His Symbols. New York: Dell Publishing, 1964.

———. The Psychology of the Unconscious, B. M. Hinkle, trans. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1952.

Koch, Walter. Aspektlehre nach Johannes Kepler [The Study of Aspects According to Johannes Kepler]. Hamburg, 1952.

Lewis, Marcia. The Private Lives of the Three Tenors: Behind the Scenes with Placido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, and José Carreras. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Group, 1996.

Morton, Andrew. Diana: Her True Story. London: Pocket Books, 1992.

Neumann, Erich. Depth Psychology and a New Ethic. Eugene Wolfe, trans. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1969.

———. The Origins and History of Consciousness. R. F. C. Hull, trans. Bollingen Series XLII. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954.

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Introduction by Robert Graves. London: Hamlyn (1959) 1977; London: Prometheus Press (1959) 1974.

Sakoian, Frances and Louis S. Acker. That Inconjunct-Quincunx: The Not-So-Minor Aspect. Washington, DC. Privately Published, 2nd ed., 1973.

CHAPTER ONE

What Is a Yod?—Technical Background of the Yod Configuration

A yod is an aspect configuration where one planet (MC, Ascendant, or a planet) forms an inconjunct with two other zodiacal points, while these two planets form a sextile between them. In a yod either the MC or the Ascendant can participate, but because we don't draw aspects between the MC and the Ascendant, they can never be involved in a single yod at the same time. [Jod comes from the Hebrew word  ‘jod’ = hand.]

‘jod’ = hand.]

Astrology recognizes a number of different aspects that form a “closed” configuration; for instance, we recognize the grand trine (whose points connect three signs of a single element), or the grand cross (or square), whose points connect the four signs of a single mode, and so on. The direction the interpretation of any aspect configuration takes is determined, for one, by the meaning of the kinds of aspects involved, and by the planets involved. More is going on though. In order to understand thoroughly what aspects are all about, aspect configurations in general, and the yod in particular, we will sidestep a bit and look at other astrological rules and interpretive factors so we can bring these together later on at a deeper level in discussing the yod configuration.

Aspects

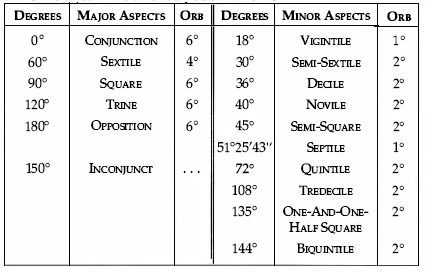

Technically speaking, an aspect is an angle a planet forms in relation to another in the sky, as seen from Earth. There are countless possible angles, but history has taught us that particular angles exhibit a clear effect and others do so less or not at all. After Kepler, classification according to so-called major and minor aspects was recognized; the major aspects were traditionally the conjunction (0°), sextile (60°), square (90°), trine (120°), and opposition (180°). These are all angles divisible by 30, the number of degrees comprising a whole sign. At that time, aspects were considered exclusively with reference to sign. The only two aspects missing from this list of major aspects that are also divisible by 30 are the semi-sextile (30°) and the inconjunct (150°). These used to be minor aspects.

By combining music and numerology with the concept of astrological aspects, Kepler created many new aspects. He was familiar with the inconjunct (also called a quincunx), but also made totally new ones. Because Kepler came up with quite a few aspects whose angles were no longer divisible by 30, the problem arose, for instance, that you could get a quintile (72°) between the signs Aries and Cancer (i.e., a planet at 29° Aries, and the other 72° further at 11° Cancer), but also one between Aries and Gemini (i.e., a planet at 2° Aries, and the other 72° further at 14° Gemini). He gave aspects their own meaning based on music and numerology, and the angles that belong to the aspects were, from Kepler's time on, pretty much considered from a strictly mathematical point of view, rather than from the sign where the planets were placed. This meant changing the traditional manner of reading the chart, where a planet was inseparably linked to its sign and where the sign was of considerable importance when thinking of aspects.1 In the old days, as Greek sources report (think of Ptolemy), it was even the case that aspects were not seen as having an orb, but only used as “whole-sign” aspects.

For example: every planet in Aries, regardless of the degree was considered to be sextile to every planet in Aquarius, again regardless of the degree in which that planet was located. The reason for this was that Aries and Aquarius are sextile, and any planets located in these signs, because of their background, will also have a sextile-tendency to each other.

However, if you ignore the background sign when interpreting aspects, you will arrive at very strange combinations and encounter conflicting readings. For example: if you only look at the angle (the distance in degrees) as a mathematical given, then you'll see the 120° angle (with an orb, of course) between 29° Aries and 1° Virgo as a trine because the aspect is 122°, and falls within the effective range due to the allowed orb. However, the planets involved never work on their own; they are also colored by the sign in which they are placed.

Although Mercury always remains Mercury as such (representing such things as our way of talking, combining facts, and thinking), it will inevitably exhibit itself differently and express itself differently in Aries than it will in Taurus. So when interpreting an aspect, we can't just say that Mercury is in this or that aspect, but must first describe Mercury in greater detail in connection with its sign.

Let's say that in our example, we have Mercury at 29° Aries and the Moon at 1° Virgo.2 What are these planets doing? Mercury in Aries will talk and think in the way of fire—rapidly and in broad terms. This is a Mercury that wants to take the world by storm, sees countless possibilities, smells adventure, and in this way combines facts and comes up with ideas. This Mercury will almost stumble over words when speaking, which he does enthusiastically, at full throttle, and with zeal. He might even blurt out all kinds of things. Details and the concrete material world are completely lost sight of. But not Moon in Virgo. This Moon will feel the most comfortable if it can direct itself at concrete reality, at what is tangible and can be experienced by the senses—at that which offers security. This Moon in Virgo has the most trouble with the insecurity of adventure and chasing after countless still intangible possibilities. A Moon in Virgo feels safe if it can calmly weigh things mentally and act cautiously. In fact, it is totally different and, with respect to feelings, even in conflict with Mercury in Aries. What are the implications for the trine without reference to sign?

A trine is always described as a harmonious and flexible connection between two planets that also work well together. But how is a taking-the-world-by-storm, adventuring Mercury in Aries supposed to work together flexibly and “go well with” an in his eyes inhibiting, sober Moon in Virgo with both feet on the ground who abhors adventure? Mercury in Aries' tempestuous thoughts and wrestling with possibilities are the very things that make cautious Moon in Virgo's hair stand on end! The chance that these two patterns of needs would have lots of trouble with each other and cause tensions in each other is overwhelming. However, had the Moon been located in the last degree of Leo, we would have had a trine whereby both the Moon and Mercury would be working from a fire basis. Aries and Leo are both fire signs, after all. In this case, the Moon would be truly able to appreciate Mercury's need for adventure and new possibilities, in addition to Mercury's enthusiastic way of talking about things. Okay, Leo is a fixed sign and therefore needs a bit more time than Aries, which is a cardinal sign. However, they have so much in common (fire) in terms of their orientation toward life, that they can tolerate a lot from each other. This situation certainly reflects the flexibility of a trine. This flexibility will, however, be missing from trines if there is no reference to sign. If an aspect like this, without reference to sign, no longer fits its basic meaning, is it still that aspect? In other words, can a trine, described as being flexible, still be a trine if it directly elicits tension and irritation? In my view, no, and I think we have to return to the older views, whereby the sign the planet is in is of overriding importance when interpreting an aspect.

Background Sign, Element, and Mode

Planets involved in aspects and aspect configurations are located in a sign, and therefore when interpreting these planets, the sign the planet is in plays a significant role. A sign in turn owes a great deal of its meaning to the fact that it belongs to a particular element, mode, and polarity (positive or negative sign).

Elements form ways of looking that, in Jungian terms, represent the functions of consciousness. Looking at things this way (automatically), is a big help when orienting ourselves in terms of the outside world. Even before we've thought about it, we're already busy ordering and labeling the facts and phenomena coming at us so we can give ourselves a handle on the world. Jung discovered in practice that consciousness has four different ways of orienting and looking, and they turn out to match the astrological elements perfectly. Although Jung was active in astrology, if we study the way he developed his typologies, we see very clearly that he did not derive his four function types from the astrological elements. It is therefore even more archetypal that they correspond so closely.

The four possible functions of consciousness that Jung distinguished we can clarify as follows:

—Sensation Type : Accepting something as it is and looking at how it is, for example: hard, sharp, warm, etc. Perception is primary. Considering anything not perceivable with the senses offers no handle for this way of seeing things, for this type is focused on the security of the concrete world and of the here and now: the future obviously cannot be grasped. This corresponds to the earth element.

—Thinking Type: Asking what the thing perceived actually is and how it can be classified in the current frame of reference. This type likes to look at things theoretically and strictly logically. The actions of those around, as well as this type's own actions, are seen from logical reasoning, and everything is rationally thought out and motivated as much as possible. This corresponds to the air element.

—Feeling Type: Imagining and experiencing all that is evoked by what is perceived, in the way of feelings of pleasure and displeasure, on the basis of which something will be accepted or rejected. Emotional values are important. This way of seeing also entails absorbing very subtle things of which this type is not necessarily always aware. A mood or intention will quickly be detected, and this becomes part of weighing issues. This corresponds to the water element.

—Intuition Type: (Unaware) Knowing or “imagining” where what is perceived comes from and/or how it will develop (as a possibility). In doing so, the object, as such, is often not even experienced with awareness. This is a kind of “grasping” or “seeing” of backgrounds. This is why Jung called it intuition, which is not the same as the astrological Uranus. The intuitive type is always in search of possibilities, backgrounds, and space. This corresponds to the fire element.

Planets located in a single element all orient themselves in the same way in terms of the outside world. In this respect, there is, in fact, a great mutual understanding among planets in the same element. Even when there is no question of a real trine within the allowed orb, a planet in Leo will feel comfortable with a planet in Sagittarius because they have the same orientation toward the world, and order the world around them in the same way. In earlier times, astrologers already remarked on this, and there was a time when all planets in Leo were considered to be trine to all planets in Sagittarius, due to their mutual understanding and the similarity in their way of looking, even though things were described differently back then.

However, Leo and Sagittarius each belong to a different mode. Each element consists of three signs, and these three signs all belong to different modes. Modes are involved in the way we tackle the problems we encounter, in our ways of coping with things, and in the flow of our psychic energy. There are three:

—The Cardinal Mode: Signs that belong to this mode cope with their problems best by insuring their place in their environment and/or by directing themselves toward the outside world or to those around them. The ways in which their environment plays a role can, however, vary greatly. For instance, you might need people around you in order to rebel against them, or to play a little contest with them (Aries), in order to be able to experience the impetus of emotions (Cancer), in order to effect compromises (Libra), or to execute them (Capricorn), just to give you a couple of simplified examples.

—The Fixed Mode: Copes precisely by withdrawing inwardly and shutting out the environment outside, so completely opposite to the cardinal mode. Fixed signs can psychically or literally “shut themselves up” and sit and brood until they come out of it. As long as they haven't come out of it, they won't bother about whether they're being “sociable” or “taking those around them into account.” Fixed signs are definitely not asocial or antisocial, but need both time and space with problems to collect themselves again. It is not a question of unwillingness if something doesn't work; their inner world just hasn't become activated yet.

—The Mutable Mode: Mutable signs tend to seek out all kinds of ways first, so they can move on, and run the risk of thinking that their problems are already (almost) solved the moment they spot them. Or else they are so busy “clearing rubbish” that they forget to stop and consider the seriousness of their problems. They are capable of continuing quickly and picking up the thread again, but often after the fact will suddenly become aware, on a deeper level now, of what was actually wrong, and may still have to cope with it.

Planets that are located in different signs, but in the same mode, will cope with their problems in the same ways, but they will see their problems differently, because seeing depends on the element of the sign. Let's consider the signs Aries and Capricorn. They look at the world totally differently. However, if they have problems, they will both, each in their own way, want to do something in or with their environment in order to feel good again, and to have the feeling they can handle the world again.

Between Aries and Capricorn, there is another difference at work: Aries is a positive sign and Capricorn is a negative sign. The difference between the polarities is:

—Positive: Tends to take the initiative and to proceed to action. This polarity symbolizes the need to do something and to handle it instead of waiting. Likes to have the helm in hand. This polarity represents a facet of yang. Signs: fire and air signs.

—Negative: Tends to acquire an idea of what all is wrong, first. Needs time and feels more comfortable looking around first, and then responding. This polarity therefore waits for the first action, then proceeds to action—reactive, in other words, instead of taking the initiative. This polarity represents a facet of yin. Signs: earth and water signs.

It is always the case with an aspect that if your psyche is doing something with one kind of subject matter (meaning one planet), and harnesses it, as it were, all the other planets with which it is in aspect will be jumping to join in. And they will quickly start interfering, and so start to color the action or effect of the subject matter you harnessed. The books describe Moon in Taurus as being tranquil, but you should see when a person with Moon in Taurus has Uranus in an aspect to the Moon. Then, most definitely, restlessness and speediness come into play!

So, except when a planet is an unaspected planet, it never stands alone, and will always be involved in other energies. Those other planets, however, aren't located in a void. Their effect bears the stamp of their placement in an element, in a mode, and in a polarity. Then the question is which of the planet's signs will “color” the aspected planet and which will not. In an aspect pattern or configuration, such as a grand trine, a grand square, a kite, or a yod, to name only a few, it comes down to a complicated interaction of all kinds of factors that determine the interpretation.

Backgrounds of Aspect Configurations or Patterns

The planets in a grand trine are always located in a particular element. There are four elements. This means that we have four kinds of grand trines: a fire, an earth, a water, and an air variety. Two of these elements belong to the positive signs and two to the negative. As a result, two of the four possible grand trines belong to the “positive” variety and two to the “negative.” The words positive and negative should not be considered in the popular sense, but in the sense of action—yang (positive), and reaction—or yin (negative). If we are talking about the grand trine, we should always keep in mind that there are various kinds, which of course have consequences for interpretation.

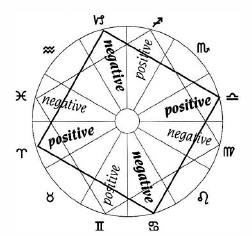

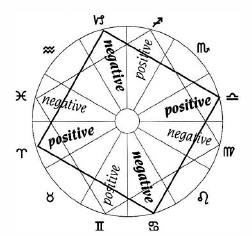

Another example: In a grand square, the four planets involved are located within the same mode, so therefore in a cardinal, fixed, or mutable mode. The signs involved, though, are all in different elements. A grand square involves two positive and two negative signs. The structure of a grand square is therefore different in its make-up from that of a grand trine.

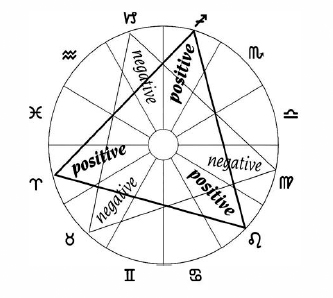

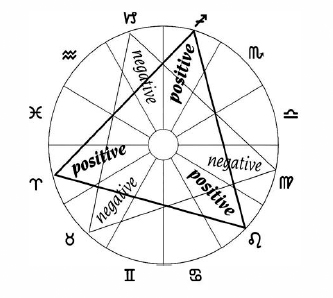

Planets' signs are an important component of interpretation, and are an essential part of reading an aspect pattern. When an aspect pattern has a similar orientation, the effect of that pattern will be flexible. Planets involved in a grand trine all have the same orientation to the world because the signs the planets are in involve the same element. And all three will have either an active or a reactive approach, depending on whether the grand trine is in positive or negative signs. The only thing that differs in a grand trine is how the planets cope with things: the modes are different. But, if orientation and the way of reacting lie in the same line, there is coordination without friction, so that very little tension is elicited. Considering that modes primarily have to do with coping, the fact that no tension is elicited will insure that the presence of three different modes in a grand trine doesn't necessarily lead to problems. (See figure 1, page 9.)

The situation presented by a grand square is very different. Here we have four different ways of looking at a situation because there are four different elements taking part. (See figure 2, page 10.) This also means that one of the four always belongs to the inferior or unconscious function. Four different orientations imply tension and conflict. Although it is true that the signs involved in a grand square belong to a single mode, so that the tension will be approached and coped with in a single way, within that grand square we have two signs that are positive (yang), and two that are negative (yin). Consequently, some of the participants in a grand square will immediately want to proceed to action (yang) and some will want to wait and respond to coming impetuses (yin). In the tension among the various ways of seeing and coping, there is some fishtailing between the tendency to proceed to action in actuality or just not right away.

These examples of the grand trine and the grand square show that simply by looking at the role of the background signs of the planets involved, we can gain good insight into the meaning and effect of aspect patterns.

The Inconjunct and the Yod

A yod consists of two inconjuncts with a sextile at the base, and one of the points involved can be the Ascendant or the MC instead of a planet. The inconjunct, also sometimes called the quincunx (Lat.: five-twelfths), plays an important part. It is an aspect where the planets or points involved are at a distance of 150° from each other, and where only a small orb is allowed.

Figure 1. The grand trine. The positive (or yang) trine is a grand fire trine and the negitive (or yin) trine is a grand earth trine.

It is remarkable that this aspect simply was not studied, or was considered to be minor for so long, although this has fortunately changed over the last decades. This aspect is not new. Johannes Kepler referred to the 150° aspect and describes it as “cutting sharply.” Koch, who analyzed Kepler's study of aspects, describes the aspect as a “clearly splitting tendency that sets both possibilities in clear-cut opposition to each other.”3 In his view, it indicates limitations and disappointment, because the situation insists on a decision.4 With the quincunx, we would tend to look only at the opportunity that was missed, and not at the one that was realized. We will have to understand the inconjunct if we want to be able to interpret a yod.

An inconjunct is formed by two planets (or by the MC, ASC, or a planet) that are five signs apart (a sign is 30°, and 5° × 30° = 150°). These signs will belong to different elements, different quadruplicities, and different polarities: if the one “leg” is negative, then the other will be “positive.” Take the sign Cancer, for instance, to start with. From there, two inconjuncts can be formed: one to Sagittarius and one to Aquarius (five signs to the right and to the left). Cancer is a negative sign, a sign that waits and responds. The two signs with which Cancer can make an inconjunct, Sagittarius and Aquarius, belong to the positive signs, those that don't want to wait, but want to be the first to proceed to action.

As far as the elements are concerned: Cancer is water, Sagittarius is fire, and Aquarius is air. No similarity in orientation here, because the background elements are different. And as far as the modes are concerned: Cancer is a cardinal sign, Aquarius is a fixed sign, and Sagittarius is mutable. The result is that the difference in orientation (the background element) and the difference in positive/negative nature can lead to tensions. In order to be able to handle that stress and to cope with problems, it's best to use one of the modes. Each of the modes copes in its own way. In an inconjunct there are two modes, however, and each of the points involved wants to tackle the problems in a different way, which causes the stress to increase. Based on the analysis of the background signs involved, we conclude that the inconjunct is a combination of signs that are not compatible and that tends to step up the tension even more.

I have noticed that the role of the distinction between positive and negative signs in aspect configurations is significant, more significant than often appears from the literature. Just look at the sextile. It consists of two signs that are different regarding element as well as mode. But they have a similar nature, either positive or negative. That agreement in proceeding to action immediately or not helps compensate for the difference in orientation. A sextile is always between air and fire (positive signs) or water and earth (negative signs). The sextile also has some tension because of the differences in orientation (element) and coping (mode), which is also noticeable in the discussion of the sextile. It is true that it is seen as a friendly or harmonious aspect, but sometimes it is seen as an aspect that lends insecurity, and what it promises we won't get for free. We'll still have to work hard for it, unlike with the trine where it all comes together more rapidly.

Figure 2. A grand square. The heavy lines indicate a cardinal square and the lighter lines show a mutable square.

An inconjunct is therefore a troublesome aspect. We might say that the planets involved don't understand each other's worlds at all. Those who work from the Jungian study of elements distinguish two kinds of inconjuncts: those where the signs involved relate in an inferior-superior way and those where that is not the case. Jung emphasized in his practice that that there are four ways in which people orient themselves in the world outside. Not only are these four mutually exclusive, but each type of orientation or function of consciousness results in its opposite remaining unconscious. He distinguished the following four functions, which are linked in astrology to the following four elements:

| Thinking |

= |

Air |

| Feeling |

= |

Water |

| Sensation |

= |

Earth |

| Intuition |

= |

Fire |

For a thinking type (air), the orientation of feeling (water) keeps working from the unconscious; for a sensation type (earth) the orientation of intuition (fire) is unconscious. Jung referred to a superior function where the type that we “are” is concerned, or the orientation of consciousness (astrologically reflected by the Sun). The psychological function opposing this, which remains in the unconscious, he called the inferior function.

Astrologically, we get the following polarity if we work from the Jungian view: air versus water and fire versus earth. (For a detailed analysis and further explanation of this, see Psychological Astrology and Elements and Modes as Basis of the Horoscope.5

This way of looking at things has major consequences for an inconjunct, because an inconjunct that has air-water or fire-earth as background signs will have an even harder time of it than when air-earth or fire-water background signs are involved. So in our example using Cancer, the inconjunct between Cancer (water) and Aquarius (air) is more troublesome than the one between Cancer (water) and Sagittarius (fire). Although the latter pair is under sufficient tension simply because an inconjunct happens to be that way.

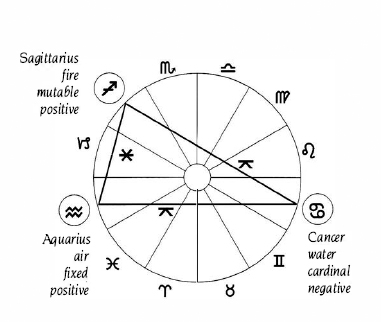

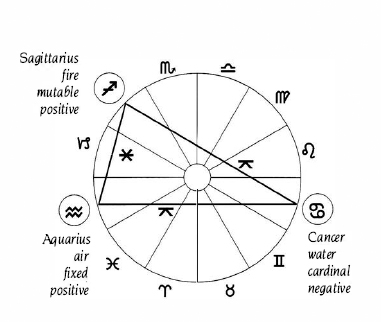

A yod, as we saw, is an aspect configuration with two inconjuncts from a single point, with a sextile forming the base. Let's take a look at the signs involved to gain more insight into the tension in a yod:

• A yod links three planets that are each in different elements.

• A yod links three planets that are each in different modes.

• The top of a yod always belongs to a different polarity (positive or negative) than do the points linked by the sextile at the base.

• Of the two legs of a yod, one always has the extra superior-inferior stress.

If we consider Cancer, again, as an example (see figure 3, page 13) we see the following: three modes are involved in the Yod, so three different motivations and needs for coping; Cancer is negative and prefers to wait, Aquarius and Sagittarius are positive and would prefer to proceed to action right away.

We know that all the planets that are in aspect to a planet, or a point, have the tendency to interfere as soon as we activate or “harness” the planet or point involved. However, as we were able to see above, a planet does not work with its own pure energy, but with an energy that gets channeled through the sign in which it is located. For a yod, this means that should the planet in Cancer be activated, to stick to our example, the other two “legs” of the yod, those in Aquarius and Sagittarius, want to join in and intervene. If the planet in Cancer wants to see based on its own feeling and experience, the planet in Aquarius will object and will intentionally place a mental vision in the foreground. With a Cancer background, the planets in this sign tend to become more conservative and direct themselves at their immediate environment. And this again is something that the Sagittarius background resists, because it really wants to see things in a broad perspective, and to look farther than the end of its nose.

We see the same kind of problem with a T-square: for instance a planet in Aries (fire) square a planet in Cancer (water) oppose a planet in Libra (air). There are three elements here as well. This always provides a solid basis of tension, and as soon as stresses and problems start occurring, two other mechanisms come into play: the necessity of coping (the modes) and the necessity to do something actively, or positively (the positive/negative polarity).

The T-square is similar to the yod in that the positive/negative polarity is also under tension. After all, for both the yod and the T-square, one of the points involved is in another polarity than the other two. In our example of the yod, Cancer is negative, and Sagittarius and Aquarius positive. In the example of the T-square, Cancer is negative, Aries and Libra positive. For both the yod and the T-square this adds inner tension, because one part of the aspect wants to proceed to action and go at it, while the other part wants to wait and see which way the wind is blowing.

So, double tension in a yod (as well as in a T-square) is due to the combination of three elements and the tension of polarities. This strengthens the necessity of coping inwardly and coming to terms with the dynamic that arose. And therein lies the big difference between a T-square and a yod: in a T-square all the points involved are in the same mode, and will cope with and mull over a problem in the same way. In our example, Aries, Cancer, and Libra are all in the cardinal mode, and someone with this T-square will cope in a “cardinal” way. In order to deal with problems, people with this T-square will direct themselves at the outside world and want to experience and affirm their role there, after which they will be able to cope again. With a yod, things aren't that simple. Here the three points of the yod are each in a different mode. Therefore, if the first point is cardinal (Cancer, in our example), this point will want to direct itself at the outside world and want to do something in it, even if only to make things more sociable. The positive feedback will then give it a feeling it can move on again. But the fixed point (Aquarius, in our example) is directly opposed, and will want to force the participants in the yod to turn inward and not pay any attention to those around them. This point has to mull and brood in order to cope again, and the “cardinal” leg makes it nervous, because it makes it lose its center. The “cardinal” leg, however, is made nervous precisely by the “fixed” leg, because the fixed mode wants to pull it to its inner world and that isn't something that makes the cardinal mode feel comfortable, and is certainly not a mechanism for being able to face something. On the contrary, this only makes it feel worse. And the mutable leg (Sagittarius here) can offend the other two by either acting as if nothing's wrong, or ending up in all kinds of escapist activities that have nothing at all to do with the problem, getting around to coping only later. And just as the other two are starting to come out of it, it will cause problems.

Figure 3. A yod is formed between a sextile and two inconjuncts.

Even though this explanation may seem a little black and white, it does describe the essence of the problems with a yod: there is no agreement, none whatsoever, among the three participants. The ways of looking differ (the elements), the tendency to action or reaction differs (the polarities), and if something needs to be coped with, the participants will be all over one another! So, turbulence and agitation, insecurity, and instability are the result. If we tally it all, there are three elements, two polarities, and three modes. Three plus two plus three is eight. In fact, the three participants in a yod are located in eight different “worlds”!

Once we understand how signs are constructed and how they color the effect of the planets, we will immediately gain additional insight into the effect of aspect patterns. In the literature on yods it is occasionally claimed that a yod might have a kind of 6th-8th-house meaning: from Aries, both of the other legs are located in Virgo and Scorpio, the 6th and 8th signs, after all. And even aside from the fact that you could also take starting points other than Aries and get very different meanings, I think the dynamics of a yod can be understood a lot better from the structure of the signs involved.

Orbs

Another important technical issue is the question of orbs. An orb is the allowable deviation in degrees to either side, measured from the exact point within which the aspect is still valid, or still works. There is no unequivocal opinion about orbs in astrology, but with regard to yods there are a couple of things we need to consider.

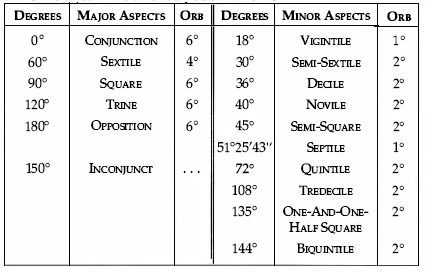

The aspect reflects an angle of 150°, five whole signs. It has been consigned to the minor aspects for a long time, but nowadays is considered major by many. This is why this aspect is also granted an orb appropriate for a major aspect, an orb that is much bigger than that granted the minor aspects. Table 1, below, lists the aspects by their angles, so we can see see which problems the 150° presents concerning orbs.

Now imagine that you give the inconjunct an orb of 6°. Thus it is supposed to work between 150° − 6° and 150° + 6°, so it has a reach from 144° to 156°. However, if we look on the list of minor aspects, then we see that 144° is a biquintile, and that this aspect has an orb of 2°. In other words: the biquintile (with a totally different meaning and interpretation) works from 144° − 2° to 144° + 2°, and has a reach from 142° to 146°.

Table 1. Major and Minor Aspects and Orbs.

So, if we grant the inconjunct an orb of 6°, then it overlaps considerably with another aspect, the biquintile. Epstein, in his book about the inconjunct, even grants this aspect an orb of 8°, so that the inconjunct completely overlaps and swallows up the biquintile. He believes a larger orb is also possible.

There is, therefore, a large theoretical problem here, and we must be aware of it before we start working with an inconjunct. Duly considered, there are two possible choices:

• Either we leave the minor aspects totally out of consideration and allow a large orb for the inconjunct;

• Or else we take the minor aspects seriously and allow a small orb for the inconjunct.

So we can only allow a large orb for the inconjunct if we consider the minor aspects to be ineffective, unimportant, or unnecessary. In all other cases there is a maximum limit for the inconjunct of 4 degrees of orb: 150° − 4° = 146°, and this is the outer limit of the biquintile. There is still always the question as to whether there is a blank zone between two aspects, so a zone without aspect effects, or whether there is a sharp border. If we assume a blank zone, the inconjunct can take an orb of a maximum of 3° to 3.5°.

Personally, I use an orb of three degrees. That's safe, and in practice we see the inconjunct working itself out very clearly with this orb. However, I have a number of examples where an orb of 3.5° still showed indications that agreed with my experiences of an inconjunct—where one of 4° no longer did. This means that I hover between an orb of 3° and a maximum of 3.5°, but for reasons of safety I will not go any farther than 3° in this book. And as I already pointed out, I work with aspects exclusively with reference to sign.

The Points

In investigating and working with yods, it has consistently been the case that the yod exhibits its characteristics particularly when the points involved are planets. One of the three may be the Ascendant or the MC. Planets are psychic motivators and dynamics that provide the needed movement. This movement is brought out through the angles, or more specifically, the MC or the Ascendant.

Horoscope factors, such as the nodes or the Part of Fortune, are of a very different order; in any case, they are not psychically dynamic. My experience is that these last cannot be full-fledged participants in a yod configuration. As my knowledge about and insight into yod configurations grew, it became clear to me that yods limit themselves to planets, the ASC, and the MC. This is the reason why I do not discuss the nodes and angles as “legs” of a yod in this book. I particularly doubt that they have any effect in this aspect pattern.

‘jod’ = hand.]

‘jod’ = hand.]