The House of Black and White

My Life with and Search for Louise Johnson Morris

By

David Sherer

Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co.

E-book edition © 2014

Print edition © 2014 David Sherer – ISBN: 978-1-62857-521-7

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the permission, in writing, of the publisher.

Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co.

12620 FM 1960, Suite A4-507

Houston TX 77065

www.sbpra.com

ISBN: 978-1-63135-021-4

Dedication

For Louise, Chester, and Christopher (whom I never knew)

Acknowledgments

This book has been more than two and a half years in the making. It has been quite gut-wrenching at times, and on many occasions, for varying reasons, I felt I should have thrown in the towel. Although I feel, in some respects, that this is a “risky” book to write, thankfully, I persevered. This “risk” comes in offending family, the black community, and members of my own faith. My intention is to tell a story so personal and with themes so central to who I am that I am willing to takes these risks. My last intention is to offend.

There have been many people crucial to its creation. First, I would like to thank Chester Lee Morris, Louise Johnson Morris’s son, for his time and energy in sharing whatever information he had about his life with and without his mother by his side. Thanks also to the entire Johnson family -- each and every one -- of Macon, Georgia, Louise’s hometown, where I was treated like family.

I would be remiss not to mention the gracious hospitality of Dr. Thomas R. Flynn, distinguished professor of philosophy at Emory University, for his continuing friendship and support and for being my host on my many trips to Atlanta. Gratitude is due Diane Hull, LCSW-C, as well, for her insights and wisdom. Photographer Rick Waldroup has my thanks for his kind sharing of information about the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells, Texas.

No amount of gratitude can express my reliance and tribute to my excellent editor, Tracy Quinn McLennan, whose oversight of the project has made it, I feel, a worthy work. I’d also like to thank Bill Adler, Jr., a fellow writer and friend, for introducing me to Tracy. I would like to thank my outstanding cover designer, Kim Abraham, for putting a creative and artistic face to this work. My brother, Daniel, has been of enormous help, both for his brilliant and creative Archives as well as his literary and artistic insights.

Thanks go out to my mother, Leah L. Sherer, who shared stories and ideas concerning the dynamics of our family. Though we don’t always see eye to eye, her tales of older times give color and completeness to the work. I hope that she agrees we have achieved a “state of grace.”

To those who have cheered me on these few years by Facebook, in person, and by other means, I say, “Thank you, all.” You know who you are. Gratitude is due, as well, to author Gary Krist for his helpful advice. Thank you to my excellent publishing team at SBPRA and to steadfast childhood friends, Stephen F. Dejter, Jr., MD; Michael Kolker; Lee Burgunder; and Richard Carroll.

Finally, thanks Laura, Liam, and Bangles for sticking with me.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Foreword

Chapter One: The “Home-House”

Macon, Georgia

Spring 1937

Chapter Two: House of Peace

Silver Spring, Maryland and Somerset, Maryland

1959-1962

Chapter Three: House of Pain

Bethesda, Maryland

1962-1965

Chapter Four: House on Fire

Bethesda, Maryland

1965-1969

Chapter Five: House of Cards

Bethesda, Maryland

1969-1976

Chapter Six: Homes Away from Home and Visits Home

Atlanta, Georgia; Boston, Massachusetts; and Miami, Florida

1976-1989

Chapter Seven: From House to House

Weezy: The Missing Years

1947-1959

Chapter Eight: Close to Home

Chester and Discovery

December 2011

Chapter Nine: On the Road to the “Home-House”

Macon, Georgia

January 15, 2012

Chapter Ten: Celestial House

Naples, Florida and Macon, Georgia

April 5th and 14th, 2012

Afterword

Epigraph

Both read the bible day and night, but thou read’st black where I read white.

William Blake

1757-1827

Introduction

The name “Bethesda” comes from the Bible. With origins in both Aramaic and Hebrew, it literally means “house of mercy” or “house of grace.” It is also where the Bible states miracles occurred; the lame were healed there as the angels swirled the waters in the “Pool of Bethesda.” Its significance can be considered twofold: It was both a place of disgrace, owing to the collection of invalids who came there, and a place of grace, where the unwell came and were made well.

Bethesda, Maryland, a thriving and bustling suburb of Washington, DC, is where I spent most of my childhood between 1962 and 1976. Louise Johnson Morris, the African American woman whose life is the center of this work, lived with my family all of those years.

Our house was truly one of duality -- a house of mercy and pain, a place of joy and sorrow, a house most certainly of black and white.

Foreword

The granddaughter of slaves, Louise Johnson (later she added “Morris” to her name after her second marriage) was born in Macon, Georgia on March 10th, 1922. She lived a long and challenging life under extraordinarily difficult times in our country for people like her. Like thousands of African American women of her generation, she courageously left her home to find out about the world, make a living, and perhaps to find a life’s mate and have a family. She also learned much about herself. Little did she know that she would become -- for me and many who knew her -- a great teacher. Her common sense, humor, knowledge of the Bible, warmth, work ethic, and sense of self-sacrifice made her many friends and admirers.

In the almost twenty-two years that I knew Louise, she became indispensable to my overall development, sense of self, and even emotional health. She lived with our family during highly charged and unusual times, and her interactions with our friends and neighbors left them with a biding affection for her. Even these many years later, the mere mention of her name to people who knew her evokes an automatic smile.

In the course of creating this work, it has been a challenge to piece together Louise’s past due to a multitude of factors, including scant documentation, incomplete oral history by family members, and a paucity of recollections by any of her friends and acquaintances. Nonetheless, I have done my utmost with the materials I had at hand.

This memoir is an homage to her and a catharsis of sorts for me. Though memory can be faulty, all of it is true, at least from my perspective.

A note on language: In every instance in which I quote Louise’s pronunciation, syntax, and general use of her version of English, I quote it verbatim. I have used my best attempt to transcribe the sound of her use of the language, and no disrespect, prejudice, or any other form of denigration is implied or intended. Her speech represented in this work appears exactly as I heard, and remember, it.

Some of the language in this work is harsh. I mean not to offend but to present the story as accurately as possible.

Chapter One

The “Home-House”

Macon, Georgia

Spring 1937

Fifteen-year-old Louise Johnson is toiling in the morning sun. It is late spring of 1937, and the heat and humidity have come too early and ferociously even for this part of Georgia. The massive wooden plow, hitched to the straining mule, forces Louise to push harder, deeper as the stubborn southern soil yields to the blade. Most of her siblings are still asleep, a fact that endears her even more to her father, Thomas, the son of slaves. (Decades later, she would boast to me how she was her father’s favorite out of his ten children. She had always taken pride in telling me that she was the hardest working.) She pulls an old kerchief from her pocket and wipes the salty sweat from her face. Blowing the air from her cheeks, she puts the wadded cloth back into her shirt and resumes her work on land rendered more than seventy years earlier as reparations for the evil that was slavery.

Twenty years later, in Washington, DC, I am born into a strikingly different family and surroundings. The firstborn male with two older sisters, I come into the world with parents who are Jewish, well-schooled in the healing professions, and poised to improve their social standing. My ancestors, the world’s most read book says, were slaves in another place and time. That story would be immortalized in painting, opera, literature, poetry, and other high art. The story of southern slavery in the U.S. was just catching up.

Eventually, the intersection of Louise’s life with that of my family will change them all, but it is I who will be affected the most.

In the spring of 2012, after our separation of thirty-one years, I will watch with sadness as Louise’s remains are lowered into the Georgia soil, adjacent to her parents’ and a mere mile or two from where she pushed that plow.

Chapter Two

House of Peace

Silver Spring, Maryland and Somerset, Maryland

1959-1962

My first memories of Louise are vague. She stands off to the left, a figure quietly shifting above the kitchen sink, with her back to me. From where I could just rest my dribbling eighteen-month-old chin on the cold bar of the crib, it could not have been more than ten feet. The faint but distinct waft of menthol from the Noxema she used every day hung in the air. Until the time we moved from middle-class Silver Spring to sylvan and idyllic Somerset, not much more appears in my mind of her. No touch of ebony skin, no apron to bury a forehead -- just a few of the things that I would come to associate with Louise as I got a little older.

But all that changed. By the time I was two, the rambler in Somerset with the weeping willow tree, back porch, and lone swing was the perfect place for a growing mind. Somerset was everything the name implied. A hamlet of green wedged firmly between racially and religiously restrictive Kenwood, aristocratic Chevy Chase, and the Northwest DC line with enough trees, flowers, and thick grass to bury a child’s chin smile-deep. (No blacks or Jews were allowed to live in communities of “restrictive covenants.”) My father, Max, was in his first years of medical practice, having completed his fellowship in endocrinology at the prestigious National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. My mother, Leah, a former operating room nurse, was busy tending to her children. The oldest, Deborah, was five years old and Lisa was three and a half. Since my father was almost always working, I found myself surrounded by females except for our dog King, a boxer-pointer mix. My sisters spent their days during the school year at Somerset Elementary, so I was left with my mom and Louise in the house much of the time. But it was Louise, more than my mother or anyone else in my life at the time, who would eventually shape whatever ego-strengthening views of myself I could muster. Her presence would also make an indelible mark on the way I eventually saw the world.

Years later, my mother told me that Louise came to us from a notice in The Washington Post. “A-Number-One Maid Needed!” it shouted. Mom felt she needed help raising the kids, especially Lisa who had hearing and behavioral problems, so she and my father placed the ad. Louise arrived at our home on Colston Drive in Silver Spring. The two women took a liking to each other, and she was hired on the spot.

This scene played out commonly in those days in DC. Young black women, having no real chance for advancement or any semblance of a professional life, joined families as domestics, becoming cooks, nurse maids, house cleaners, and, for a want of a better term, servants. This arrangement between a young black woman and an upwardly mobile Jewish family was nothing unusual for the time and was so meaningful for me when the film Driving Miss Daisy came along decades later.

For so many poor blacks of the time, the massive migration north from cities like Atlanta, Birmingham, Jackson, and Wilmington meant work, money, and possibly a better life. The District of Columbia of the 1960s held an atypical place in the list of cities that absorbed these immigrants. Unlike Boston, New York, Detroit, or Philadelphia, Washington was, in many ways, more southern than northern. Although the nation’s capital and seat of the federal government, DC was south of the Mason-Dixon line and separated from the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, by little more than 100 miles. Gettysburg, where so many were slaughtered those hot few days in July almost a century before, lay equidistant to the north. The only physical barrier that split DC off from the South was the Potomac River, but the cultural divide between the two was often as narrow as the river’s width at Chain Bridge. Culturally, Washington was more genteel than Cleveland, more aristocratic than Chicago, and less provincial than Boston. It was in many ways, however, as segregated as Savannah or Mobile. Blacks still had separate restrooms and drinking fountains and could not sit at the lunch counter at People’s Drugs on Wisconsin Avenue in DC or Maryland. They could not swim at the famous Crystal Pool at Glen Echo Amusement Park where the whites cooled themselves after rides in the bumper cars, trying their luck at the shooting gallery, or getting their weight guessed by the carnival barker.

The Washington that my mother and I knew, despite our being Jewish, was quite different. Passable as non-Jews in the often racially and religiously restricted environment of the time, we freely moved in circles where women wore white gloves between Memorial Day and Labor Day, and men commonly wore white bucks and lightweight fedoras in summer. Our life in Somerset was unique in that it was the only time I can recall my mother being consistently happy. It was there, also, that the images and influences of Louise -- or “Weezy” as we started to call her -- took permanent hold of me. Unfortunately, the interaction between my mother and Louise, at that point in my life, remains a virtual blank.

While my sisters were in school at Somerset Elementary, Mom spent her days studying modern dance, practicing the piano, grocery shopping, gassing up the family station wagon, getting clothes for the kids, and ferrying Lisa to various doctors and behavioral specialists. I would accompany her on some of these excursions, and a big treat for me was grabbing lunch at the Hot Shoppes (one of the many creations of the early Marriott Corporation) on the corner of Wisconsin Avenue and East West Highway in Bethesda’s epicenter. Coffee was served in white china cups with saucers by waitresses (most of them were Caucasian but a smattering of blacks held the coveted job) wearing hairnets, caps, starched uniforms with cuffed short sleeves, and white shoes. Cream for the coffee came in small glass bottles with paper tab tops. My mother would lunch on egg salad sandwiches with fries and coffee. I happily ordered a hot dog and a Coke or an orange freeze served with shaved ice in a contoured glass. I wondered why the waitresses would ask if we wanted our Coke served “with or without ammonia” (a common practice at the time for “health reasons”). If we were in a hurry, we would sit at the counter where the frigid linoleum counter would allow me a vigorous forearm push-off to spin around 360 degrees on the orange, patent leather-covered swivel chair. From that vantage point, I could spy the diners down the line: business men in suits and ties, construction workers in heavy leather belts and scratched hard hats, moms with other kids, and young, pretty, lipsticked secretaries out for a quick lunch.

My mother and I would wait for the school bus to drop off my two older sisters every day after school. We would sit by the fire hydrant on Dorset Avenue in Somerset naming each car that drove by. Each correct guess earned a delicate pinch on my earlobe from my mom. Every time I pass that same hydrant this half century later my mind’s ear hears “Chevrolet, I pinch your ear.”

Compared to the middle and later years of her adult life, my mother was a different person in those days. Born in New York City in 1928, she and her mother, Hannah, soon left the United States for what was then Palestine in the early 1930s, purportedly related to my grandfather Maurice’s ambitions in the pro-Zionist movement. Her father stayed behind to earn enough money so that the whole family could be together in this new frontier. There, Mom spent an unstable childhood. With her father thousands of miles away, it was left to her to be the constant companion for her own sickly mother. Disastrously, a ruptured appendix left Hannah in the hospital and unwell for months, and young Leah had to board with relatives. To this day, my mother recounts with some bitterness having to live with her distant kin, who were virtual strangers she didn’t like, particularly her maternal grandmother whom she later called “that bitch.” By the time she had regained some of her health, my grandmother had taken her daughter back to the United States where my grandfather had opened a school for foreign languages in the south part of Philadelphia. Family responsibilities combined with the American economy in shambles had put his pioneering ambitions on hold.

As a child, my mother was bright and ambitious, doing well in school and developing an ardent interest in the piano. The family was poor and, like most families at the height of the Great Depression, got by on very little. As the 1930s wore on and the economy yielded to one of war, the early 1940s saw my mother attending the prestigious Philadelphia High School for Girls where she made high grades and developed into a talented pianist. She then attended Temple University’s School of Nursing, became a registered nurse, and moved to New York City where she worked hard, reveled in the cultural scene of recitals, the symphony, and theater, and searched, like a lot of driven young women in those days, for a career and then a husband.

Stepping into that role was my father, Max. He was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1920, the son of an immigrant tailor, Ben, and his wife, Sadie. Like my mother, he was an only child until, again like my mother, a sibling of the opposite sex came along nine years later. Young Max was rebellious, mischievous, stubborn, and clever. There are stories of him getting his head caught between the iron bars of a public railing (the Brooklyn fire department had to liberate him), of disappearing for days at a time at summer camp, and of building rock formations covered in snow and ice to not only block traffic on bridges but to delight in the damage to cars he and his buddies had just unleashed. In later years, Dad would relate how, as a stocky kid in Brooklyn, he would act as sucker-bait for his handball partner. This partner would hustle an opposing twosome and proclaim, “I’ll pick any kid from this crowd, and I’ll still beat ‘cha!” He would always pick my clunky, un-athletic-appearing father, and, together, they would deliberately lose the first game or two only to double the bet and take the dupes for all their money.

In short, Dad was a hell-raiser.

But he was an ambitious hell-raiser. He got his bachelor’s in chemistry from NYU and applied to medical school (his own polio-stricken uncle, Izzy, a urologist at the University of Iowa, was his role model) but could not get in due to quotas against admitting Jews. This gave my father an early taste of discrimination firsthand and undoubtedly shaped the way he would see minorities as kindred spirits of sorts. In all the years I knew my dad, his views toward minority groups firmly tended on the side of sympathy.

After college, he earned a master’s degree in chemistry at MIT, continued to apply and get rejected to medical school, and wandered to and from chemistry laboratories at locations as diverse as Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana to Princeton, New Jersey where, under the Manhattan Project, he had done secret work on the atomic bomb project. After the war, in 1946, he finally gained admission to the Boston University School of Medicine, finished in 1950, and moved to New York City where he did his medical internship and residency. It was there that he met my mother, an operating room nurse at New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

My mother had her marital sights set on my father’s closest friend, Herman Schwartz, who was eventually my dad’s best man at his wedding and was, according to the stories about him, medicine’s answer to Cary Grant. Mom actually dated Herman briefly, and once, overjoyed, she overheard him say in the hospital cafeteria that he was going to “marry Leah.” Too bad, according to my mother, that it turned out to be a different Leah, the well-known graphic artist, Leah Schwartz, who bagged Herman. Mom would later say that she had to “settle for my father,” a pronouncement that made me uncomfortable and wonder if we kids were the offspring of a failed arrangement from the start.

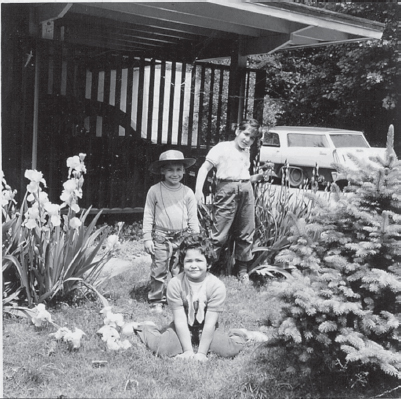

Somerset, 1961. Deb, standing; the author with cowboy hat and Lisa, foreground.