The Wordsmith

The Wordsmith

THE WORDSMITH

First published in 2015 by

Little Island Books

7 Kenilworth Park

Dublin 6W, Ireland

© Patricia Forde 2015

The author has asserted her moral rights.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system in any form or by any means (including electronic/digital, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, by means now known or hereinafter invented) without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 9781908195999

A British Library Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover and endpaper illustration by Steve Simpson Insides designed and typeset by Oldtown Creative Printed in Poland by Drukarnia Skleniarz

Little Island receives financial assistance from the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my father, Tommy Forde

About the author

PATRICIA FORDE is from Galway, on the west coast of Ireland. She has previously written picture books and early readers in both Irish and English. She has also written television drama for children and young people as well as three plays. In another life she was a primary school teacher and director of Galway Arts Festival. This is her first novel.

PROLOGUE

SMITH FEARFALL was a scavenger. This beach was his territory.

He watched the canister as it danced, nibbling the waves, teasing him. He waited. He was good at waiting. Finally his quarry came within reach. He waded out. The plastic that covered his trousers snapped and cracked in the gale. The canister moved away from him. He waited, eyes on his prey, his mind fully focused.

Once more the silver glint of the metal cylinder cut through the salty water. Smith reached out and felt the hard metal beneath his fingers. The canister slipped from his grasp. He lunged and caught it once more. He wrapped both hands around it and cradled it to his body.

Back on the beach, he examined it, the sharp sand stinging his eyes. He noted the red star and the string of letters: N-I-CE-N-E, but they meant nothing to him. He shoved the canister into his hemp bag along with the other treasures he had found that morning.

Beyond him, over the vast stretch of turbulent grey water, a gull screamed. Smith stopped and looked out to the horizon. He shivered. Then, pulling his coat closer to his bones, turned and headed for home.

CHAPTER 1

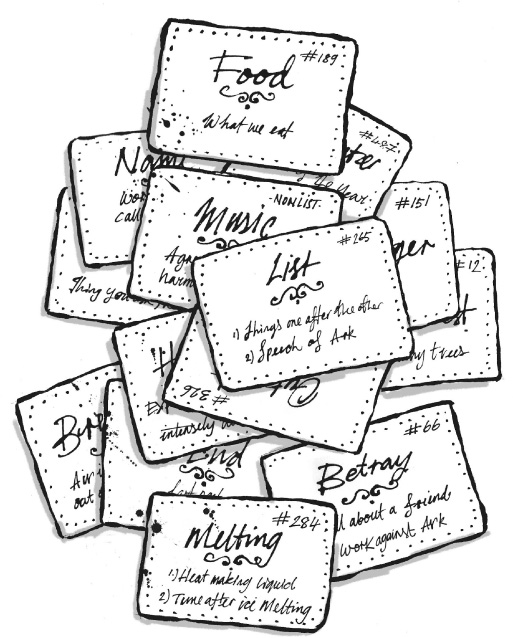

LETTA, the wordsmith’s apprentice, buried her face in her hands, exhausted. Her forehead ached and her eyes felt dry and dusty. She had transcribed hundreds of words since early morning, each one written in her own distinctive cursive style. This was their busiest time of year, the time of change. It was now that the masters took on apprentices, teachers took on new pupils and people got ready for the long winter.

She reached for another card and began to write.

Search: To explore, to look for. An investigation seeking answers

She stopped for a second, resting her pen on the edge of the table. The evening light threw shadows on the walls and added to her anxiety. She had to do something. She couldn’t sit here waiting for Benjamin to tell her why a gavver had seen fit to visit them. She got up and walked to the living area, stopping outside Benjamin’s study. There she hesitated. The voices from the inner room rose and fell, words slipping and sliding between the two men. Letta turned to the small round table and, with great care, filled the cups that stood waiting on the metal tray. Two cups. The boiling water released the earthy smell of burdock, its pungent depths filling the room, deep and claylike. She picked up the tray and moved to the door. Should she go in? Through the slit in the battened door, she could just see the heavy drapes covering the window, the old green armchair standing on its three legs, the fourth corner supported by a block of timber. Beneath it, the white marble floor, smooth and cold.

She took a deep breath and shifted the tray to her left hand. With the knuckle of her index finger she tapped a dull tattoo on the door. The cups lurched. Inside, she could hear her master’s voice.

‘But sir,’ he said. ‘Five hundred words? It not … not … human.’

The gavver’s answer came swiftly. ‘List seven hundred words now,’ he said. ‘Too many. Why make work for self?’

‘But … but …’

Letta flinched at the despair in her master’s voice.

The gavver laughed. ‘Ark need less words,’ he said. ‘Words no good. Words bring trouble.’

Letta stood frozen, her hand still raised, the hated beat of the gavver’s speech affronting her ears. The door opened, swinging towards her. Letta jumped. The tray wobbled. The gavver stood there, his tonsured head shining as though a yellow light glistened beneath the skin. With one hand he took the tray from her. He placed his other hand on Letta’s shoulder.

‘No harm,’ he said, his sloe-eyed stare transfixing her. ‘What this?’

‘Tea,’ Letta said, her heart pounding. Later, she couldn’t remember why she spoke, only that a feeling like a wave had subsumed her. ‘Burdock tea,’ she said, spitting the words at him.

The face came closer until she could feel his breath on her cheek. ‘Tea,’ he corrected her, his voice little more than a whisper. ‘Tea. No burdock tea. Burdock not List word.’

Without taking his eyes from her face, he dropped the tray, letting it clatter to the floor. The crash echoed through the old house. Letta could feel the boiling liquid splash her bare ankle. She bit her tongue to stop herself from crying out. The gavver stepped over the tray and the cups and the puddle of tea as though nothing had happened.

At the door, he turned. ‘Five hundred, wordsmith. Prepare List.’

And then he was gone. For a moment, Letta and her master stood in silence, both caught in the spell the other man had cast.

Benjamin turned to her. ‘Letta,’ he said, and she could see the hurt in his eyes, ‘no make trouble. Not good. Fail.’

‘Don’t speak List to me,’ she said, suddenly furious. ‘We are wordsmiths. We can speak as we wish.’

‘Perhaps,’ Benjamin said, his eyes darting to the door, making sure they were alone. ‘But we must remember that it is a privilege, child.’

Letta could feel the frustration bubbling up in her. She shook her head.

‘We are the fortunate ones, Letta, the last people left on this planet.’

Letta shrugged, not able to speak.

‘Five hundred words,’ Benjamin said, his voice quiet. ‘I must prepare a new List.’

‘But master …’ Letta could not keep the protest out of her voice.

Five hundred words? Could they survive on that?

‘John Noa knows what he is doing,’ Benjamin said. ‘He always knows. You’ll see.’ He reached out and touched her hand, the skin on his fingers parched and cool.

‘I’ll clean up the mess,’ she said and watched him lumber back towards the open door of his sanctuary.

She found the twig in a shadowy corner of the hall and removed the broken crockery. Through the open window, she could hear the wind moaning, and somewhere not too far away, a wolf howled as if in answer. She walked across the room and pulled the window closed, pausing for a second to look out at the bleached, wet landscape.

Across the way, the houses teetered on the side of the hill, leaning on one another for support. Small identical boxes, lime-washed, with their communal living room, two bedrooms and a toilet, all built before the Melting. In the windows, slices of faint yellow light squinted back at her, flickering giddily, as if afraid that the windmills that fed them could desert them at any minute. Further up the hill, the queue was already forming at Central Kitchen. Reluctantly, she pulled herself away from the scene outside and headed back to her work.

Through the door leading into the shop, she could see her table. The cardboard boxes nestled one inside the other, the mound of four-inch-square cards, cut the previous night, the wooden handle of her pen honed and polished until it felt smooth as glass. Beside it, the pot of ink glinted in the shadowy afternoon light. Her heart was still loud in her ears but the gavver was gone. Now, there was only herself and her words again. She moved quickly across the floor, pulled out her chair and settled down to work. She reached out and picked up a blank card.

She needed to assemble twenty List boxes for Mrs Truckle, the schoolteacher. The old lady’s voice still rang in her ears from her own school days. ‘Sit up straight, girl. Don’t dig the paper.’

The words danced in front of her eyes just as they had when she’d been a small child. She remembered lying in bed with all the words she’d learnt in school flying about her head, fireflies from some magical place, red electric fireflies.

Sometimes, soon, sound.

All List words, of course. She hadn’t known anything else then.

She turned the card over and placed it on her writing mat. The feel of the thin card calmed the turmoil inside her. She picked up her pen and dipped it in the ink, lifting it carefully lest the red dye invade the card before she could control it. She steadied her hand and pressed the nib to the vanilla-coloured paper. Slowly, the rhythm of writing and ordering the cards worked its magic, and she forgot about everything else.

School would resume in ten days and, according to John Noa’s instruction, each child would be supplied with a copy of the List, five hundred words, one word per card, one box per child. Upstairs, her master muttered to himself and stamped his feet on the old weathered boards to keep warm.

He was always cold now, Letta thought. Distracted, she looked up and surveyed the familiar surroundings of the shop.

The building groaned with the weight of its years. It was unusually big in comparison to the normal houses in Ark. The large downstairs room was the shop where Benjamin conducted business and where Letta’s desk stood, tucked away in the upper corner. Behind the shop was their living room and off that again Benjamin’s study. Within the study was another door leading to the library. There were little nooks everywhere, small spaces hiding behind bigger ones, alcoves and cellars, sprawling over a large area. Upstairs there were three more rooms.

The house had been built in another time, when people thought nothing of wasting large pieces of glass in windows and lighting real fires indoors, not for heat but for comfort. Here, in the shop, an old fireplace stood against the outer wall with a thick black beam above it. The fireplace itself was packed with word boxes and the shelf held a bizarre array of ink pots and short sticks ready to be turned into pens, along with bits and pieces Benjamin brought back from his trips.

Outside, the walls were clad with sheets of tin, reflecting the sunlight and the faces of the people who entered. Inside, behind a counter made of solid oak, from trees from another time, Letta could see row upon row of shelves, honeycombed with cubbyholes. The cubbyholes cradled the vanilla-coloured, four-inch square cards, and the cards held the precious words. Round about her were the many relics of another world, such as the big glass eye of the holographic dome, in which Letta could see her own reflection, with her sharp green eyes and shock of red hair, looking back at her.

She sighed and went back to her work, moving on to the words that were to be taken out of circulation. Those words were stored here in the shop. From time to time, Benjamin took boxes of words to Noa’s house, where Letta supposed they were held out of harm’s way. She flicked through the cards in the box nearest to her.

Dream, Hope, Love, Faith

She pulled a card at random and read it. Silently first, then out loud. ‘Dream, Dream.’

She didn’t hear the old man come in again and jumped when he spoke.

‘Dream: A cherished desire,’ he said. ‘Now where did I leave my bag?’

‘It’s here, master,’ Letta said, handing the heavy leather satchel to him, not sure whether he was annoyed with her.

‘I seem to lose things a lot more than I used to,’ her master said, taking the box and peering at a piece of paper he held in his hands.

Letta looked at him and noticed the deep shadows under the red-veined eyes, the yellow shrivelled skin that clung to the sharp bones of his face and the chalk-white hair that he brushed across his brow.

‘The new list will be ready before dark tonight.’

He didn’t look at her. Five hundred words. A major edit on the orders she had already filled.

‘Was there anything in the drop box today?’ the old man asked her.

‘Just one word,’ she said, handing him a card. ‘Ant. I met the boy who dropped it off. He found this piece of paper in an old box, but he didn’t know the word.’

‘Ant,’ Benjamin said softly. ‘How quickly people forget! When I was a boy such words were commonplace but now …’

‘Now they’re all just insects.’ Letta finished the thought for him.

He shook his head. ‘There is something I need to tell you,’ he said.

Letta waited, biting her lip. ‘Yes, master?’ she said.

‘I have to go away sooner than I thought. I’m afraid I must leave at first light.’

Letta nodded. ‘How long will you be away?’

The old man rubbed his hand through his hair. ‘I’ll be back as soon as I can,’ he said. ‘You keep the shop open. Take in the words and sort them. Distribute words to those who need them. Do you think you can do that, child?’

‘Yes, master,’ she said. ‘I can do that.’

‘Mrs Truckle will help you when she can. Just remember to keep your head down. Speak List. Don’t draw attention to yourself.’

Letta sighed. She wasn’t sure she wanted her old teacher helping her. Her master’s words cut across her thoughts.

‘There is a lot of unrest out there,’ he said.

‘Outside Ark?’ Letta pressed him, fascinated and terrified all at once.

The old man shrugged. ‘Maybe even inside Ark,’ he said.

Benjamin turned away from her and very slowly started to climb the stairs. Not for the first time, she gave thanks that she had a home here in Ark. After the Melting so many people found themselves cast adrift, lost in a dangerous wilderness with no-one to help them, but her parents had been followers of Noa. They had come to Ark before the last days, and she had been born here. Benjamin was right when he said she was privileged. There were many who had not been so lucky.

Letta pushed her thoughts to one side and set about packing a bag for her master. She went into the living area and headed straight for the water bottles. They had still a few days’ worth of water there so she took three bottles and put them carefully into the old bag. She held back only one small bottle for herself. She was sure Werber would give her more if she really needed it, but Benjamin might not come on clean water for days. His food he would collect from Central Kitchen. Mary Pepper wouldn’t be happy about it, but it was another privilege of the wordsmith. He had a duty to travel outside Ark in search of words and therefore the right to bring food with him.

She moved swiftly to the old cupboard that stood by the wall and pulled open a drawer. There were all his scraping and cutting tools. She picked them up and was about to deposit them in the bag when she paused. She took the little knife he used with its simple wooden handle and sharp curved blade. She closed her eyes, feeling its weight in her hand. She tried to imagine herself out in the field. Hauling some long-forgotten artefact from the loose soil. A box. Yes. A box that had once held exotic food. She would carefully clean away the mud and silt and there underneath she would find the label. Torn perhaps, but still readable. The words just sitting there, black on white. She would peel the label off with the knife and put it between two sheets of clean paper. And then, she would see what it was that she had discovered. A new word. A word long forgotten. Something from the other time, the time before the disasters. She wouldn’t know what it meant at first, but she would deduce its meaning from the context, or ask an elderly person who would remember it from their youth. She sighed to herself.

She needed a walk, she thought, stretching her aching back. Fresh air, a snatched break before the night’s work began in earnest. Her master didn’t like her going too far from the shop but she had to have air. She pulled on her coat, the raw cotton coarse against her skin. Benjamin had clad the coat with plastic he had found on one of his trips so that it almost kept the rain out.

The street was little more than a mud track, churned up by the passing boots of the field workers as they hurried home. She pressed on, out towards the fields, moving against the flow of traffic. A man hauling pelts passed by, his eyes cast down. Behind him a cart laden with water barrels trundled by on its way to the water tower. A group of children, freed from the harvest fields, ran past her, shouting and whooping, their tally sticks beating against their chests. She sighed. Did they know that they had just lost two hundred words? Words they would never know or soon forget?

She would walk as far as the first potato fields, she told herself, and then turn back. She would still have time to pick up their evening meal from Central Kitchen. A Monday meal. Vegetable soup, parsnip cakes and green beans. She hated parsnips.

Soon, the hustle of the village was behind her and she found herself on the outskirts of the farmland. The path climbed up between the big green fields, growing steeper all the time. Letta could feel the pull at the backs of her legs. Not enough exercise, she thought. Her chest hurt as the path grew steeper and she tried to distract herself by looking over the great hedges to where the rows of potatoes lay. As she finally crested the hill, she stopped to get her breath. She turned and looked back at the great landscape laid bare in front of her, where curving fields scalloped the murky skies. Water lay in the lower ones after the heavy rain of the last few days. Below her, the forest glowered in the evening light, surrounding the town with its secrets and its plots, casting dark shadows on their lives. To her left, the small meadow, triangular in shape, like a wedge cut out of a pie, where a gavver had been found dead last spring. She shivered and pulled her coat closer to her body. To her right, a gap in the hedge revealed the path that led to the shoreline.

Purposefully, Letta turned and set off through the mud and the puddles. Within minutes, she could smell the salty perfume of the sea and hear the water pounding on the shore. She remembered how afraid she had been of it as a child. How she would wake screaming in the middle of the night convinced that it was coming to swallow them up. It was always the same dream, always the same fear. Finally, Benjamin had taken her to the shore.

The path beneath her feet mutated and became more beach than field. She was sure that this was the way she had come that day with her master. Down this incline and straight on to the beach. She had cowered behind Benjamin, afraid to look up. She could smell it, though, and hear it: Bang, swiiish, bang, swiiish.

‘Look!’ Benjamin said. ‘See! The tide is going out. It cannot hurt you.’

She had looked up and, holding his hand, had walked down until she was only yards from the water.

‘Look!’ he’d said again. ‘See that line. See those rocks. Each year the sea gives back a little of what it took.’

She looked at it now. Its muddy green water suckling the earth, sucking its life force with it. Ghosts lingered in this place, the ghosts of all who had been overtaken by the sea, grey wispy ghosts who sighed on dark winter’s evenings and faded a little in the light of summer. Letta could feel their presence brooding in the background as she tried to imagine the awfulness of it. The towering wall of water bearing down, the screams, the vain attempts to flee. The victims of the Melting. How strange it must have seemed to see that usually docile body of water suddenly rear up against them, swallowing houses, villages, towns and cities. Cities once brimming with life; structured, ordered days; possessions; families – all gone. Drowned in the salty beast. Letta shivered. The wind had turned and was blowing from the north. She watched as the grey wisps of ghosts were caught in its breath and pushed across the sky until they blended with the steely clouds.

She missed her parents, missed them with a terrible longing, and in that instant she could feel their presence. She closed her eyes and let the feeling flow through her until it lost its force, leaving her alone and shivering at the edge of the tide.

She looked to the far horizon. Then she raised one finger and saluted them, as she always did, just in case they were out there and could see her and would know that she hadn’t forgotten them. The far horizon where they now lingered, if not in body, then at least in spirit.

CHAPTER 2

LEFT ALONE, Letta immersed herself in work. As well as transcribing words, she served their regular customers, the crafters and apprentices who needed specialist words that were not on the List.

And with only Letta to transcribe the words, the days were exhausting, though uneventful. The nights were long and dark and lonely.

She made up three new boxes of words, which had been ordered by a carpenter for his three apprentices. The boys came to collect the words themselves. They were giddy, their eyes bright with mischief, twelve years old and just finished school. Anyone would think they been apprenticed to the Green Warriors, Letta thought wryly. She had given them saw and hammer and nails and tacks, and nicer ones like plane and chisel. Twenty-five words in all, in addition to the five hundred on the main List. They’d seemed happy.

‘We ready now,’ the younger one had said, smiling.

She recognised him as one of the healer’s boys. Daniel. Or was it Crann? No. Definitely Daniel. She’d heard about him. She glanced at his tally stick. It had at least fifteen notches. Fifteen breaches of the language law.

Letta had handed him his box, making a silent wish that he would change his ways now that he was an apprentice.

After the boys left, she had prepared two boxes of words detailing thirty types of fruit that were to be removed. Pineapple had been a new word to her. List had only those fruits available in Ark: apples, strawberries, raspberries and blackberries. There were no pineapples.

Letta was about to close the shop when she heard the old wooden door rattle open.

In front of her stood a boy of her own age, but thin, the bones in his face so clear it looked as though they had been drawn there. He looked up, and Letta could see the previously hidden bright blue-grey eyes.

‘No harm!’ Letta greeted him, tentatively.

He looked about him, nervously. ‘I need words,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ said Letta. ‘What words?’

‘List words. A box of List words,’ the boy replied, his right hand pressed to the left side of his chest, his eyes darting from the front door back to her face.

Letta listened, entranced. His voice was rich and fluid, not rusty like most of their customers’. He was speaking List but not in the usual way. A box, he’d said. Perfectly legal, but most people didn’t bother with the article. Her heart quickened.

‘Why?’ she began. ‘Why need … why you need?’

The boy frowned. ‘Fail,’ he said. ‘Need words. No question.’

Letta took a step back and scrutinised him. He seemed nervous, his feet moving restlessly, eyes never still.

‘I wait my master come,’ she said, speaking carefully, only using List words. The boy’s eyes clouded over.

‘No!’ The boy took a step back, looking at the door behind him again, as if expecting someone. ‘I no wait. I hear you be wordsmith.’

Letta flinched, his words stinging like nettles.

‘I wordsmith,’ she said. ‘That … that …’ She could feel herself getting flustered. She tried again. ‘I wordsmith apprentice, but he no here, so I wordsmith for now.’

The boy raised one eyebrow, his blue-grey eyes now studying her face. His body relaxed. ‘You help me or no?’ he said, with the hint of a smile.

Letta knew he was challenging her. She pulled herself up to her full height. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I help.’

She turned to retrieve a box from the pigeon-hole behind her. As soon as she did, she remembered that she had given the last one to the tanner’s wife earlier that day.

‘Words no here. I get,’ she said, cursing her own carelessness. She had meant to replenish the pigeon-holes earlier but it had slipped her mind. Now she would have to leave this strange boy alone while she went to the master’s study. She could feel his eyes on her as she retreated from the shop.

In the study, she grabbed the keys from the nail and quickly inserted the smallest one in the library door. The key glided through the mechanism with a tiny metallic click. The heavy door fell open and Letta caught her breath as she always did when confronted with the master’s secret library. Here were the words he kept in isolation, the words forever removed from everyday use. Shelf after shelf, from floor to ceiling, packed with boxes, the boxes packed with words that would survive, even if they could never be used in Letta’s lifetime.

Nothing wasted, nothing lost. John Noa’s mantra, Benjamin’s mantra. Nothing wasted, nothing lost. If the day came that man ever needed language again, Ark would be ready.

Letta shivered. The room smelt of paper and age and a touch of mustiness. Within it lay the precious source material, the fruits of the master’s many word-finding trips, where he searched painstakingly for any last remaining relic of the written word. Box upon box of tiny bits of language, waiting to be sorted, transcribed and filed. On one wall a tattered banner hung from a nail, its words faded and worn: In the Beginning was the Word.

Most people could read a little, but rarely saw the written word, apart from the odd poster with information from John Noa, or their little box of words from school. The sea had swallowed the written word after the Melting. The very thought caused a shiver to ripple through her. For a second, she doubted the wisdom of what she was doing. Would her master have given words to this stranger? She hesitated. What harm could it do? He was entitled to the List. Though why had he not been given the List by his master?

She picked up one of the boxes from the desk and headed back to her customer. As she passed the orderly rows of shelves, her elbow touched a box that had not been properly replaced. It tumbled from its perch and landed at her feet. She jumped as the box fell and an avalanche of cards hit the floor. She bent down and picked up the box. On the front written in her own steady hand a word looked back at her: Colours. She hastily stuffed the cards back into it. She would take it up to the shop and sort it later, but for now her customer was waiting.

She hurried through the door to where she could see the counter. At first she thought the boy had left, and then she saw him, or at least she saw his hand on the cold marble floor. His hand, and then his arm, and then his chest, and the crater the bullet had left, and the thick red soupy blood, and then she heard the high-pitched scream of a young girl. It took her a full five seconds to realise that it was she, Letta, who was screaming. Screaming, even as the precious box of words fell from her hands and the cards fluttered to the floor: crimson, sienna, indigo, cobalt, ochre and gunmetal blue.

Letta was about to run onto the street when she saw his hand move. He was alive. She knelt on the cold floor and put her shaking hand to the boy’s throat. His skin felt warm and smelt of wild sage. He moaned.

Letta jumped back in fright. ‘Quiet now,’ she said, her voice trembling. ‘I get help.’

She started to rise but his fingers grasped her hand. He tried to lift his head.

‘No,’ he said. ‘Must hide. They will find me.’

‘Who? Who will find you?’

The sound of a siren suddenly rent the air. Gavvers. Letta jumped up and, yanking down the cloth that covered the shop door, she slammed home the great bolts. Then she went back to the boy.

‘Can you get up?’ she said, abandoning all efforts to speak List.

He groaned as he bent his knees and tried to transfer his weight to his hands. Letta grabbed him, pulling him up and almost knocking herself over in the process.

‘Put your arm around my neck,’ she said, her breath rasping. The blood from his wound dripped onto the floor – scarlet in the beam of light that fell from the window overhead. Letta put her hands under his arms and half-dragged, half-carried him up the stairs, down the long corridor at the top of the house. At one point he stumbled and fell against the old wood-panelled wall. The wall gave, revealing an ancient hidden space where Letta had played as a child. It was known as the Monk’s Room, though no-one knew why. For a second, the boy lay on the floor looking up at her, then turned towards the hidden space.

‘No further. Leave me … here.’

His words were sticky, she thought, as though adhering to his lips.

‘No!’ Letta said, and with another heave, she got him to his feet and pulled him the last few strides, to where her own small room stood. There, she let him fall onto her bed. He groaned, a sound like air leaving a tired balloon, and lost consciousness.

The room was small, with only her bed, a chair and the old cupboard that Benjamin had made for her, leaning against the wall. She pulled the chair to the side of the bed.

It was then she heard the banging on the door. She looked from the boy to the door. The banging continued, louder and more aggressive. Letta could hear her own heart almost as loud, hammering in her ears.

A moment later she drew back the heavy bolts on the front door and found herself looking into the face of a gavver. Letta took in the dull grey uniform of John Noa’s law enforcers before her eyes travelled to the face above it. The face had few if any saving graces. A bulbous nose spread across it, and above that, two small hooded eyes. His mouth was a thin wrinkle, no lips, just a fold of yellowing skin. Letta inclined her head and listened to his raspy voice.

‘Wordsmith here?’ he asked, his eyes fastening first on her face, then taking in the blood on the floor, the cards scattered on the white marble.

There was an air of aggression about him that frightened her. She shook her head. ‘Master on word-finding –’ Too late she remembered there was no list word for trip or journey. She hesitated. ‘He away word finding,’ she said, the clumsy words thick in her mouth. ‘He no back for short time.’

She waited for his response. He took his time formulating his next question.

‘Where boy?’

Letta frowned. ‘No understand?’ she said, creasing her brow into a puzzled mask.

The gavver snarled, pointing at the blood on the floor. ‘Boy! Where he go?’

‘Run away. I don’t know,’ Letta said.

The gavver’s hand shot out and slapped her across the mouth. Letta tasted the dull, metallic blood on her tongue just before he grabbed the collar of her shirt and pulled her close. ‘Where boy?’

She struggled to answer. Struggled even to breathe. ‘I … I don’t know. I tell you. I don’t know.’

His grip tightened. Letta’s eyes bulged in their cavities even as little black dots started to dance in front of them. Just then, the door burst open, and a second gavver stood there, red in the face and panting loudly.

‘Carver! Come!’ he said. ‘Down lane! He hurt, but able run!’

Carver swung round, releasing Letta reluctantly, and started for the door.

‘That way!’ his colleague shouted.

As soon as Carver left, the second man turned to Letta and, with a barely perceptible nod to the stunned girl, he was gone.

Letta released a long slow breath, putting her hand to her bruised throat, feeling her lip thicken and swell. Then she slammed the bolts home for the second time and stood, her knees weak, her head spinning. She looked down at the congealing blood on the floor and the word cards lying helplessly beside it. Once more the siren screamed outside. But this time Letta felt it was screaming at her, and it was only a matter of time before they would return for their quarry. Her eyes went to the door behind the counter and the boy she knew waited for her at the top of the stairs.

Letta took away the cloth that covered his wound, her fingers moving gently, her eyes darting from the bandage to her patient’s face, worried lest she hurt him. It was healing already, the wound drying out and crusting over. As she watched him, his eyelids flickered, and slowly the eyes opened.

‘It all right,’ Letta said quickly. ‘You safe.’

He tried to sit up, then fell back against the pillow, his face white and drained.

‘Easy,’ Letta said. ‘Rest.’

‘You wordsmith.’ His voice was ragged, his breathing shallow.

‘Yes,’ Letta said. ‘Wordsmith. Letta. What your name?’

‘Marlo,’ he said and closed his eyes again.

‘Marlo,’ Letta repeated softly. ‘Marlo.’

She let him sleep then. She had closed the shop and brought her work upstairs with her so that she could fill the school boxes for Mrs Truckle, but she found it difficult to concentrate. The night had fallen quickly and outside rain lashed the street and beat on the window.

She shivered. What had she done? She had no idea who the strange boy was. He wore a tally stick, but, when she examined it, there was something not quite right about it. Normal tally sticks had a mark burnt on the base. The mark was an individual one, no two the same. This tally stick had no such mark. It was illegal to interfere with the tally stick. She looked at it again. It had three notches on it, showing he had broken the language law three times. Twenty breaches meant expulsion from Ark. There were other things too. When she had removed his shirt she found old scars on his back. Large black shadows where the skin bloomed, black as night. She had heard of the Black Angel. Hurts and heals at the same time. She had asked the master about it once but he had brushed her questions aside.

‘Not something you need to worry about,’ he’d said. ‘Do your work. Keep your head down and the law will have no truck with you.’

Yet she couldn’t erase from her memory the face of the gavver who had slapped her. Instinctively, she put her hand to her swollen lip. He had treated her like a criminal. Criminals had always been shadowy creatures to her, people bent on the destruction of the new world; bandits who roamed the forest; or the surly inhabitants of Tintown. Yet here she was, harbouring someone who could be a felon, maybe even a Desecrator. She pushed that thought away, but the question still nagged her. Who was he? She picked up a card and started to write.

Plough: Break and turn over earth

He was no farm boy, she was sure of that. His hands were clean and soft. A healer? Perhaps. She looked at him again. A sheen of sweat glistened on his forehead. He moved his head restlessly.

‘Finn!’

Letta went to him.

‘Shh,’ she said. ‘Relax.’

‘Finn!’ he cried out again. His eyes shot open, bright with fever.

Letta stepped back.

‘Don’t tell them about the pump house,’ he said. ‘Don’t tell anyone. North of the river. We mustn’t betray them. The gavvers …’

He started to climb out of bed. Letta moved quickly.

‘No, Marlo,’ she said firmly. ‘Lie down. No gavvers. Rest now.’

She pushed him back onto his pillow and was relieved when he closed his eyes again. It was the fever, of course. She knew that, but it still frightened her. And he was speaking the old tongue, not List, throwing words about in an easy, fluid way, not thinking about where to find them, confident that they would come.

Betray, he’d said. It was such a rare word. She had only recently learned it herself. Deliver to an enemy by treachery.

Who was he? Excitement filled her body, little bubbles bursting in her brain. A wordsmith? Was it possible? But Benjamin was the last wordsmith. That is what they had always believed.

Over the course of the night, Marlo grew stronger. He still muttered in his sleep about Finn and the pump house. He mentioned other names too, Carmina and George, but he was growing calmer. Letta bathed his head with cool water just as the first rays of the morning sun peeped through the window. She pushed the long strands of red hair out of her eyes and wondered what her master would think. The boy opened his eyes. She noticed how beautiful they were, blue with flecks of grey, like the sea on a calm day. She smiled.

‘What you thinking?’ Marlo asked.

Letta hesitated, then decided to tell him part of the truth. ‘I was wondering what my master would think if he saw you here. That’s all.’

Marlo frowned.

‘No speak List?’ he said, and she could see the watchfulness in him.

‘I know you speak the old tongue,’ she said. ‘You’ve been talking in your sleep.’

‘Oh,’ he said, looking sheepish. ‘Did I say anything interesting?’

‘No,’ Letta said. ‘Mostly nonsense. But, tell me, where did you learn to speak like that?’

She waited. He said nothing. Then she asked him the question that had been buzzing in her head during her long vigil. ‘Are you a wordsmith?’

Marlo laughed. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Lol! I am not a wordsmith. The people who reared me – many of them have good language. That’s all.’

She stopped, taken aback. ‘Lol?’

‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It means “laugh out loud”. L.O.L. See? My uncle Finn taught it to me. It’s an ancient expression that was handed down through his family.’

‘Laugh out loud,’ Letta said, mentally promising to write it down as soon as she could. ‘Isn’t it funny that they said it instead of doing it! I wonder did they say “cry bitterly” when they were sad?’

She took up her twig and began to sweep the worn wooden boards.

‘They probably hadn’t time,’ Marlo said. ‘They’d just have said CB.’

‘Lol,’ Letta retorted, and they both laughed.

He sobered first.

‘So what would your master have done with me?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think he would have allowed you to die on the shop floor,’ Letta answered. ‘You might have bled on the words.’

He smiled.

‘Feeling better?’ Letta said.

Marlo reached out his hand and pulled her towards him. She felt his finger on her lip.

‘What happened to you?’ he said, looking at her, his head on one side, a frown tightening his forehead.

Letta was caught off guard by the sudden question. ‘Nothing,’ she said, pulling away from him. ‘Just a small accident. Nothing important.’

He lay back on the pillow again and she saw a cloud descend on his eyes.

‘I had a dream last night,’ he said. ‘I dreamt I was a hare, a small brown hare, and when I looked up, I saw eyes in the undergrowth, red eyes, watching me.’

‘It was just a dream,’ Letta said. ‘It may be the fever.’

Marlo shook his head. ‘There’s always truth in dreams. Don’t you know that? We have to learn what they mean, that’s all.’ He paused for a second.

Letta waited, fascinated. He knew the word dream. An abstract.

‘Do you dream, Letta?’ he asked so softly that she had to lean in to hear him.

‘Dream?’ she said. ‘Sometimes I dream of words. Especially if I’ve been working hard.’

‘What words do you dream of?’ he asked.

Letta shrugged, suddenly self-conscious. ‘I don’t remember,’ she said, though she did. She had always dreamt of words. Beautiful words, haunting words and, last night, terrifying words.

He lay down and a few minutes later Letta heard the now familiar sound of his breathing as sleep once more overtook him. She rubbed a hand across her eyes.

In the shop, their stock of regular words was running low. Mrs Truckle had already called twice. Letta would need to stay up all night just to fill the orders she had.

Even so, she couldn’t resist sitting on the small armchair beside his bed and watching him. His face, so well formed, like something that had been sculpted out of a piece of rock. The curly black hair, damp with perspiration, the long lashes lying casually on the sallow skin and the smell, always the faint smell of sage. She breathed it in and resisted the impulse to trace the shape of his face with her finger. She had never seen anyone so exotic. She ached to know what his story was. What was the pump house he talked about? Who were his friends? She longed to talk to him, to know everything he knew. Why were the gavvers chasing him? Was he a criminal? A thief? A murderer? He didn’t look like one, she thought, but then what did thieves and murderers look like? Benjamin had met plenty of both in the early days, after the Melting. Gangs who roamed the earth, killing for food, killing for shelter, killing for the sake of it. Remnants of them still lived deep in the forest and were a constant threat to Ark.

She should never have taken him in, she knew that. She had brought danger right to their door. But there was something about him, a spark of energy like she’d never encountered before.

Excitement.

She got up and, with one last look at his sleeping face, left the room, pulling the door behind her.