For

David Danladi Luginbühl

Always remembered, always loved

Music forever

1974-1997

ONE

The door swings out upon a vast sea of darkness and of prayer. Will it come like this, the moment of my death? Will You open a door upon the great forest and set my feet upon a ladder under the moon, and take me out among the stars?

—Thomas Merton

The Sign of Jonas

It breaks my heart to see her lying there, worn out, dying. But she is so happy to see me, and to see Jack, and this elates me.

And I am more than glad to see Jack too. I am renewed. It has been so long, so very long. And I have searched so far.

But Margaret. Oh, Marg. My princess. That this should happen to you. That I can do nothing about it.

My daughter. My first.

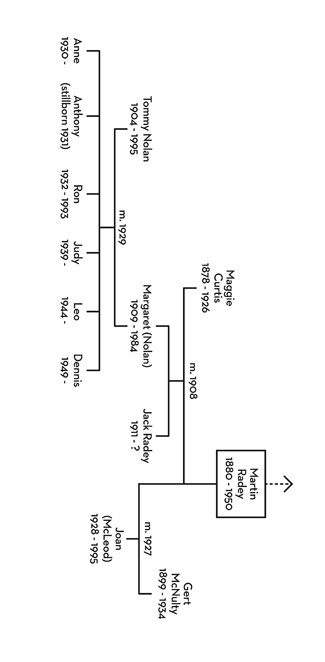

It is 1984. I am in the Women’s College Hospital, Toronto. She is seventy-four. I look around, at the beds, the curtains, the tubes. The wrong place to die: a waiting game without dignity.

And yet she is older than I was when I died. I had the good fortune to die of a heart attack on the streetcar. But I was only seventy.

We are both too young. Everybody is too young.

I reach out, touch her face.

So does Jack, my son, whom I have not seen for more than fifty years. I do not understand how it is that he is here with me, nor why he is still a young man in his twenties, but I accept it as one of death’s gifts. I understand very little anymore. Death has not taught me what I thought it might.

Margaret smiles, her eyes smile, knowing, understanding, and I think I might die again, just by seeing this. I know, suddenly, that there is not much more time. I do not know how I know this, nor what it means. And I have no idea what will come next.

One’s life is supposed to flash before one’s eyes when death comes. This is not true. It is no mere flash. It is much more complex. At least, it was for me. There is reflection. There is travel along the arc of space and time, back to source, ahead to destiny. I have been traveling for thirty-four years. I do not know how long it will last.

Something awaits me. Something. I know it. I feel it.

I am close. So close. Finally. Jack. Margaret. Here with me now.

It is part of the wonder.

Part of the mystery.

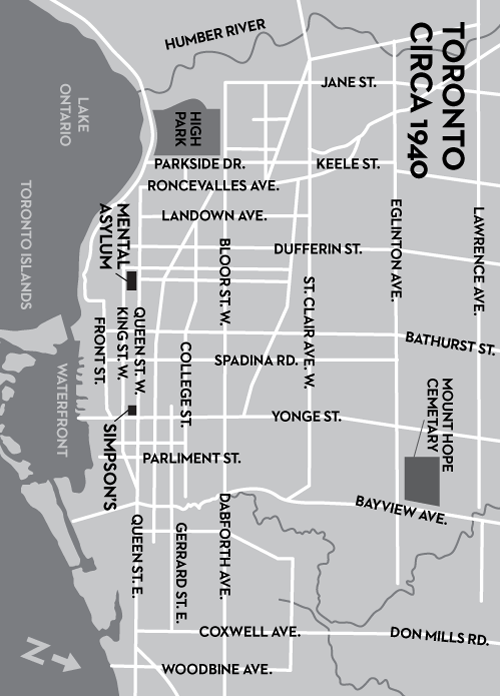

It was Christmas Day, 1950, a Monday—back before the subway was built, when the streetcars still ran up Yonge Street in Toronto and snaked on rails around the city everywhere, clanging, methodical. I was sitting in an eastbound car, on Dundas near Bloor, looking out the window, thinking about the eventual walk along Eglinton Avenue, about the icy wind that would burrow through layers of clothing— thinking about Dennis, my newest grandson, who would be two years old in March, and how much he would enjoy Christmas.

And it happened. I imagine that it has happened, and will happen like this, to millions, to billions, before and after my time—that it was happening to others even as it was happening to me. A complete surprise. So much surprises us, and yet so little should.

It was my turn to die.

I was coming to see you Marg, coming to spend the day. We hadn’t spent enough days like this.

The pain filled my chest, but it didn’t last long. Not really. I understand more now about time than I did then, and in reality it was merely a cosmic eye blink. I looked at the woman seated beside me, a stranger, said, “I can’t breathe.” My left hand clutched the chrome rail on the back of the seat in front of me, while my right hand instinctively squeezed the stone in my jacket pocket, the one given to me that day in the garden by the monk—that day in the sunlight. This stone is life, he had said.

I squeezed it fiercely. I thought of Joan, Margaret, Jack, then died.

Death has not been what I expected.

Not that I knew what to expect. I did have some concrete images in my head once, images that had blurred to vague concepts over the years, of a God, an afterlife—from being taken to church as a child, from my parents, from catechism lessons so many years ago. Nor would I have been terribly astonished if nothing at all had awaited me—a leaf fallen from a tree, becoming soil.

The streetcar shuddered to a stop, the woman next to me clutching my arm in fear and real concern. I heard a muffled hollering, knew confusion, as all that made sense slid away, like a morning dream. The conductor appeared beside me, and within seconds the car was being cleared of passengers. From far off, I heard him announce that the trolley was out of service and was proceeding directly, with all haste, to Western Hospital.

I remember looking out the window, from deep within me, through whirling, dying eyes, watching a flock of starlings rise up in widening circles from the pavement in a floating wave, a current toward the heavens. And as I watched, as I died, I became one of them, leaving my body behind, spiraling high above the street, the winter sky crisp, clear, seeing the interstices of streets below with an acuity of vision that I had never had before.

And then a kind of sense returned, a new order. This is what happens, I thought: a new clarity, a new vantage point.

I saw ahead to Yonge Street, north to St. Clair, farther to Eglinton. I tried to see Maxwell Avenue, running south off Eglinton, and the semidetached house that held much of what was left of my family, waiting for me.

Where you were, Marg.

Then I climbed higher, swooping with the flock, wondering where we were going, where I was going.

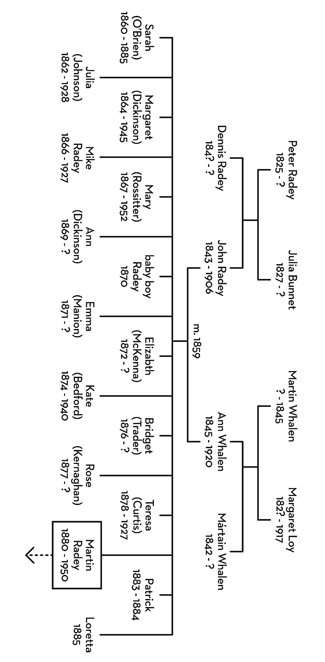

My name is Martin John Radey. I was born in Elora, a village some sixty miles northwest of Toronto, in 1880. I have been dead, as I stated, for thirty-four years. I accept what has happened to me, but I do not understand it. Perhaps acceptance is the beginning. Maybe understanding never comes.

I am the youngest of thirteen children who lived—eleven sisters and a brother. There were sixteen of us, if you count the three babies who died. We were all born in Elora.

Now we are all dead.

Back in 1950, as I soared high on the winds, the winter air searing the new, tiny lungs, I wondered, with a burst of incredulity and exhilaration, if I would see my two brothers, who died as infants, or any of my sisters—my big sister, Sarah, who died before my fifth birthday, or little Loretta, five months old, who died later that same summer of 1885—my mother, my father, here in my new existence.

And Gert. Maybe Gert. Maybe Maggie. The thought startled me, exploding a rainbow of memories.

The flock circling me leaned in unison into an updraft, left wings tilted downward, and as one we barreled north and west. My heart, stopped forever in the body below us on Dundas Avenue, had been replaced by one beating wildly with wonder.

Ahead, the horizon arced and rolled as we left the city behind, and below us the calm, brown and white winter landscape spread far and wide in soft refuge. And then I realized that I knew where we were going. We were going to Elora. I was heading home.

Flying low over the fields around Elora, the snow disappeared. Time vanished. The past was here, to be felt, viewed, examined.

I could see the old house on McNab, the post office in Godfrey’s shoe store on Metcalfe Street, the carpet factory, the old bridge across the Grand. The Tooth of Time was there, the stone fang jutting from the rapids beside the mill, as always.

Suddenly: summer. Gardens with flowers, vegetables. Elms, oaks, maples. The tannery, the brewery. The town hall, the Dalby House, the sawmill. Cords of hardwood, piled high. Horses.

And Father’s shop, right beside Mundell’s furniture factory. Where it used to be.

Through piercing avian eyes, above the earth, free, in death, I saw things and places that I had forgotten, and a past I never knew.

And above us, a single, hawk, wings motionless, circling, entered a cloud. With new instincts, I watched for it, waited. It did not come out.

Father and Mother were Irish Catholics. They had liked to tell the story of how they’d come as children on one of the coffin ships—so-called because famine, cholera, typhus, diphtheria, and every other sort of blight sailed with them—that slid from Cobh, which the English then called Queenstown, in Cork Harbour. My mother, Ann Whalen, was one year old when she left Ireland in 1846. John Radey, my father, was three. The ships destined for North America docked at New York or Boston if they were headed to the United States; the cheaper passage was to British North America, up the St. Lawrence to Quebec City, then Montreal, before turning about and heading back across the Atlantic for another raft of human flotsam.

My father and his brother Dennis were in the arms of Peter Radey and his wife Julia, themselves twenty-one and nineteen. As with one-year-old Ann Whalen, her brother Mártain, and her mother, they took the cheaper passage; after the ordained quarantine at Grosse Isle in the St. Lawrence, all disembarked at Montreal, from whence they made their ways, along with so many others, by barge, steamboat, and lake boat, to Toronto. There was the special landing wharf, then the fever sheds at King Street West and John Street. That summer, more than eight hundred died in the sheds. Catholics mostly, they were buried in trenches in the graveyard at St. Paul’s Church on Power Street. Even the bishop himself, ministering to them, died of cholera.

Eventually, it was by foot, wagon, and stagecoach over corduroy roads into southern Ontario, establishing themselves as best they could in the strange, new land. They settled, along with several other families, in and around Guelph for their Erst decade, then finally in Elora, when Da and Ma married and Da learned to be a blacksmith.

We were all born there. From 1860 to 1885, Ma had thirteen babies who lived, and three who didn’t. I was born in 1880, the last survivor; I remember Patrick and Loretta, the babies who died in 1884 and 1885, and then there were no more. My oldest sister, Sarah, died of consumption, just before Loretta was born. Sarah, Julia, Margaret, Mike, Mary, Ann, Emma, Elizabeth, Kate, Bridget, Rose, Teresa, and then me.

I spent the first seven years of my life in Elora, until we left for Toronto in 1887. Moving to the city was an astonishing idea to me. I had been there only once, when I was four years old. We rode on the Grand Trunk Railway, to see Gramma Whalen, who lived in a strange stone building that Ma told me was called the lunatic asylum, and who did not know who I was. The building had a big shiny dome on top with a water tank in it that let everybody inside have running water, and Ma took me up the round staircase to the top of the dome to see it. I remember staring at the tank, picturing the wonder of water flowing into the rooms below like magic.

After twenty-seven years, Da abandoned his blacksmith shop, the soot and the fire, the ash settling everywhere about him. The city held the promise of husbands for his girls, husbands that they would never find along the banks of the Grand.

TWO

1898

1899

1

The advertisement in the August 10, 1898, Edition Of THE Toronto Telegram newspaper reads Wanted—Diningroom girl, Nipissing Hotel, 182 King East at George.

“I’m going to apply for it,” says Rose.

Ma looks at her, unsure.

“I can’t keep working at the asylum. It’s making me crazy. I’ll be as crazy as them soon.”

“Father.” Ma looks at Da for help. He is smoking his pipe, rings of the sweet smell floating everywhere in the kitchen.

He shrugs. “I don’t see the problem.”

It is not the answer that Ma wants, and it shows on her face.

He knows this and continues. “It would make me crazy to work there.” Then he looks at his wife. “It would make you crazy.”

She presses her lips together, frustrated. Then: “But Gramma.”

He shrugs. “Rose can’t be expected to devote her life to that place just because Gramma Whalen is there.” He pauses. “Let her go, Ann.”

Watching them, Rose’s face is torn. She has never taken such a stand before, and even if she wins it will seem like a failure.

Ma sits, holds her head in her hand, thinks.

It is September. I am working at the head office of Don Valley Pressed Bricks and Terra Cotta, 60 Adelaide Street East. I am eighteen years old, and with my first pay envelope have purchased a nut-brown, American-made man’s fur felt hat, unlined, with Russian calf-leather sweatband, for two dollars at Simpson’s, which I now place jauntily on my head as I head out the door.

It is five o’clock and it is Friday. The day is over. I am meeting Lillian at the Nipissing where Rose works. It is walking distance from both of our offices, and Rose will, as always, slide a bottle of Pabst beer our way.

Lillian is nineteen, has soft black hair, small lips, a filament of scar along her chin. She likes to touch my hands, my hair. I can think of nothing but her since we met at the St. Francis dance in the summer. The Cinematographe on Yonge Street last Saturday cost me fifty cents for the two of us, but since that time my head and loins have been whirling: she kissed me, her tongue touching mine.

I am surrounded by sisters. I am used to women. I think I understand them. But Lillian proves me wrong, proves me an innocent. Because I want her, because it seems possible to have her, my thoughts stop at her body, where they pivot and slue, caress and probe. I plot and scheme to be alone with her, to touch her, to let her touch me. I know about sin, about honor, about being a gentleman, but these things evaporate when we are together, and I am only what I am. And what I am is new to me, powerful and exciting.

October, in the hayloft of the barn at Boyd’s farm, off the Dundas highway, near the Humber, I lie across Lillian’s softness and kiss her deeply. The rest of the church group is off on the hayride and will not return for an hour or more. We are not the only couple that has stolen away, but we are the only ones here, now.

I kiss the scar on her chin, her throat, touch her face, her shoulder, her arm. She holds me close, tightly, kisses me back, murmurs. She lets me open her clothing. I touch her everywhere, my mind fogged with desire. The knife-edge of frost hovers in the still air, our breaths misting slightly.

We make love. It is my first time, as it is Lillian’s. I am thrilled, relieved, shaken, terrified. And Lillian, sweet Lillian. She clings to me, and I understand suddenly the weight of what we have done, what I have done. The aftermath of emptiness and confusion leaves me embarrassed. I think of my sisters, my mother. Women will never be the same, now that I know. And I think of Da, and glimpse his life as if through a dusty window for the first time. I had always wanted to be like my father, back in the blacksmith shop, back by the sureness of the forge, when sparks lit the air. But not now, not the way things are now. Now his life does not look all that enviable to my widened eighteen-year-old eyes.

“She expects me to marry her,” I tell Mike. My brother is thirty-two, has been married seven years, has three children—Mary, Bill, and the baby, John, named after Da.

“You’re too young,” he says.

I shrug.

“Are you shaggin’ her?”

“Jesus, Mike.”

“Course you are. That’s why she expects you to marry her.”

“You’re happy, aren’t you?” I ask. We are sitting on the front verandah of his house on Gladstone Avenue.

“Mm.” He pauses, thinks. “Happy’s a funny word. I love my kids and my wife, if that’s what you mean. But happy? I don’t know about happy anymore. I don’t know what it is.” He looks around. “Half the time I’m scared. This place costs us eighteen dollars a month. Even a small furnished room with privileges would cost you twelve a month. Can you afford that?”

I shake my head. “No.”

“Then what’re you thinkin’ of? Are you goin’ daft?” But he smiles. “There are ways of doin’ it without gettin’ her pregnant, you know.”

It is my turn to smile. I am enjoying my big brother’s confidence, his knowledge that I am finally a man.

“You want to end up swallowin’ Carter’s Little Liver Pills every day like Da, complainin’ about chest pains, stomach pains, every other sort of pain, while a horde of kids runs around your ankles?”

“Like you? Is that what you’re saying?”

Again, he smiles. “You’re too young. Don’t get caught.” He passes me a Sweet Caporal cigarette, takes one himself, and together we smoke them.

2

Because it is a beautiful day, this Friday, the nineteenth of May, Lillian and I leave the Nipissing early while there is still light, walk north along George to Queen, then the half-dozen blocks east along Queen toward Lillian’s parents’ house in Irish Cabbagetown. The terrain of merchants and industry, thrift and enterprise, hope and ambition stands out hard and clear, the slanted sunshine flashing off glass facades:

Ball & Co., Men’s Furnishings, Hats & Caps, 218 Queen East.

John Patton’s Boot and Shoe Store, 224 Queen.

Wm. Tafts, Gents’ Furnishings and Dry Goods, 226 Queen.

John J. Waters, Flour, Hay & Grain, 239 Queen.

George R. Fawcett, Men’s Suits, 240 Queen.

C. R. Stong’s Groceries, 252 Queen.

F. Belknap, Fish, Fruit, Vegetables, 260 Queen.

W. Muir, Hack, Coupe and Livery, 272 Queen.

J. R. Hancock, Suits Tailored, 275 Queen.

W. Mackenzie, Furniture, Stoves, New & 2nd Hand, 280 Queen.

R. A. Cardwell, Practical Hair Dresser, 282 Queen.

Geo. Hawkins, Fresh Meat & Provision Merchant, 288 Queen.

Robt. Fair, Hardware, 290 Queen.

A. A. McKay, Millinery, Shoes, 294 Queen.

Abbott’s Meat Market, (Trading Stamps), 322 Queen.

E. J. Convey, Boots and Shoes, 330 Queen.

William Moore, Butcher, (Fresh & Salt Meats), 340 Queen.

J. W. Mogan, House & Sign Painting, 345 Queen.

Herbert O. Charlton, Furniture, Carpets, 347 Queen.

G. H. Moody & Co., Fresh Meat & Vegetables, 350 Queen.

The 9 Little Tailors Co. Ltd., 352 Queen.

R. W. Hislop, Baker and Confectioner, 356 Queen.

Geo. F. Moore, Conveyancing (Deeds, Wills, etc.), 359 Queen.

We turn south onto Power Street, where Lillian lives with her mother and three brothers. On our left is St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, then the House of Providence—its spacious grounds and dignity housing the aged, the orphans, the destitute. Lillian lives across from it, atop Osgoode Dairy, at number 82.

In the tall grass by the woods beside the Don River north of Cabbagetown, in spring, sexually exhausted, clothes disheveled, Lillian and I lie entangled side by side. I roll over, shield my eyes from the sun, dizzy from the passion of the interlude. Then I drop my hand from my brow, close my eyes, and through sun-spotted lids I see that my boyhood is gone forever.

THREE

Eternity is in the present. Eternity is in the palm of the hand. Eternity is a seed of fire, whose sudden roots break barriers that keep my heart from being an abyss.

—Thomas Merton

The Sign of Jonas

There are so many illusions. There is the illusion that our life is all of one sweep, that it has a beginning, a middle, an end—that there is some shape that can be discerned. But instead of shape, I see now, there is texture, a surface composition mingled with a basic substance, woven from some primordial loom. Some of the threads intertwine tightly, some loosely, some are dead ends needing to be snipped. Many are soft, others coarse. They all wear with time, fraying, rotting with the rains and winds and the dryness of the sun.

We live several consecutive lives, and each time we look back on our previous life it is with wonder. Sometimes it is with fondness, other times with shame, but always with wonder.

Everything changes, replaced completely. And we move on, forward into the future, unraveling, shrinking, expanding, thinking that we are going somewhere.

How often have I stood with hand on doorknob, entering a room, and wondered how did I get here? Or stared out a window at my surroundings, listening to those with whom I live, and wondered how did this all happen to me?

And then we die, and the next surprise befalls us: there is more. And still, nothing is clear, except that the Day of Judgment is ongoing, in constant session, and that we are not punished for our sins, but by them.

The flock—my flock, I now think of them—was squawking, whistling, preening, in the branches of a great maple tree. I had no desire to disengage myself from them, and this intrigued me too. Why did I not fly off by myself?

I was not what I seemed, so I was convinced that they may not be what they seemed either. And when we sat there, resting, what did they await? When we flew, what did they see? The world, I know now, is mystical, not magical: mysteries that human reason cannot plumb.

I stared down at the city, through the hole in time, and saw the cleansing, the conflagration begin.

FOUR

Tuesday, April 19, 1904

The Queen’s Hotel

Fine cuisine, courteous staff

210 boudoirs, 17 private parlors

Running water to all rooms

Telephone in lobby

Accommodation for 400 guests

Private garden, fountains

100 Front Street West, Toronto

“I’ll be twenty-four years old in less than two months,” I say.

My boyhood friend, Jock Ross, sitting across from me in the lounge of the Queen’s Hotel, pours his second bottle of Carling’s Ale carefully down the side of his tilted glass and nods. He watches the foam rise to a proper head before he smiles.

“So is that a complaint or a boast?” He sips the ale, sighs, sets it down, stares at me, eyes twinkling. “You’re in your prime, same as me.”

It is past seven o’clock and we have been sitting here since we finished work. “So what’s going to happen to you and Nancy?”

Jock looks surprised. “What do you mean?”

“Isn’t she on about marrying?”

He shrugs. “They always are. So what?”

“How do you put them of?”

“It’s a talent. A gift. You should know that.” He strokes the end of his moustache, still smiling.

I smile in return, sharing some imagined masculine confidence. Then: “Does it bother you?”

“What?”

“That you’re deluding her.”

“I’m not deluding her. She’s deluding herself. I’ve promised nothing.”

I sit back, thinking. Jock is an Orangeman, something that meant nothing to me when we were boys. Now it is an irony that we both view with amusement. Yet I wonder if there is some fundamental difference in our outlook that is rooted here.

My sister Teresa married Peter Curtis, a molder at Massey-Harris, last year. The wedding was enormous. Emma was maid of honor; his brother Fred, who works as an attendant at the asylum, was best man. The year before that it was Elizabeth who got married—to Jim McKenna, and I was best man, with Kate as maid of honor. There were one or two weddings a year it seemed. I danced with Peter’s sister, Maggie, but now I cannot picture her face when I try.

“You want to end up like your father?” Jock asks.

Yes. No. I don’t know.

“Not me. I’ve seen how my old man’s been eaten alive with the responsibility.” He sips his ale. “He’d give his eye-teeth to be here with us right now, doin’ this.”

I allow that this is true, but the argument still does not satisfy. “There must be more.”

“There is. And I’m going to see Nancy later to indulge in it.” A wink.

“Don’t you want your own place, your own family?”

“Someday.”

“When? When is it time?”

“Don’t know. I just know it isn’t time yet.” He pauses, serious for a moment. “I guess you just know. I guess it depends on the woman.”

“And Nancy?”

He frowns, thinks, dodges the question. “I tell you, Martin. It all scares the hell out of me.”

“But living at home with our parents? It’s got to end.”

He concedes this with a nod. “That it does.” Then he smiles. “Maybe next year.” He empties the rest of the bottle into his glass. “And what about you and Kathleen?”

I smile, shrug. I know what he means. Lillian is a memory, as is Suzanne, Judith, others. Kathleen will join them, inevitably. And Harriet. Dear Harriet, back in Elora, my first girlfriend, my childhood love. Her head resting on her forearm, soft hair cascading across her wrist, her other hand laboring over the printed letters in the notebook on her desk in Miss Lecour’s class. Gone like a wisp of smoke across the hills, from a time that I can scarcely comprehend.

And a new smoke wafts toward us from the present.