“Walking Among Us is a chronicle of human experience that contradicts every current theory about the universe that we think we live in. Jacobs' human observers have experienced a concealed reality that is literally next door to some of us, and that he believes is about to interact, secretly and insidiously, with the rest of us. Walking Among Us explains why extraterrestrial UFOs are here, who is aboard them, and what they are doing. To put it mildly, the evidence from the people that Jacobs has interviewed shows that the extraterrestrials are up to no good. You will find Walking Among Us hard to put down. If enough of us read and pay attention to the evidence in this book, we might be able to avoid the disaster that its evidence portends.”

—Don C. Donderi, PhD, associate professor (retired) of psychology,

McGill University, Montreal, author of UFOs, ETs, and Alien Abductions

“David Jacobs has written an extremely important book about UFO abductees and the meaning of their abductions.”

—Ron Westrum, PhD, emeritus professor of sociology,

Eastern Michigan University

“Once we accept the extraterrestrial origin of UFOs and that the beings can act purposefully as rational beings invariably do, it is only a small step from UFO phenomena to the co-residency of the two species. It is this logical consistency that makes Walking Among Us constantly grip our imagination with such vengeance.”

—Young-hae Chi, D Phil, faculty of Oriental studies,

University of Oxford

“David Jacobs has spent his career as a history professor at a major university, and—what matters most of all—he backs his claims with an impressive mass of evidence. . . . Jacobs treats his subject with ethnographic depth and detail, but without academic ponderousness.”

—Thomas E. Bullard, PhD, board member, Center for UFO

Studies and Fund for UFO Research and

author of UFO Abductions: The Measure of a Mystery

Published by Disinformation Books,

an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

with offices at

665 Third Street, Suite 400

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.redwheelweiser.com

Copyright © 2015 by David M. Jacobs, PhD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

ISBN: 978-1-938875-14-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available upon request.

Cover design by Jim Warner

Text design by Frame25 Productions

Cover photograph © Menna / Shutterstock

Printed in Canada

MAR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Disinformation® is a registered trademark of The Disinformation Company Ltd.

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

To Irene

My wife, my best friend, my advisor, and my bastion of common sense.

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Back Story

1. Abductees and Their Testimony

2. Abductees, Aliens, and the Program

3. Preparing Hubrid Children

4. Training Adolescent and Young Adult Hubrids

5. Field Training for Hubrid Integration

6. Integrated Hubrids

7. Adjusting to Life on Earth

8. Learning about Relationships

9. Training Abductees for The Change

10. Integration and Speculation

Appendix: Evolution of an Abduction Researcher

Endnotes

Index

A variety of people helped me bring this book to life.

Carolyn Longo has transcribed most of the hypnosis sessions for over twenty years. She says she never grows tired of the accounts.

My wife, Irene, edited an early draft of this book and provided her usual excellent advice. As the book evolved, my older son, Evan S. Jacobs, supplied very cogent critiques and editing of not only my writing but my theories as well. Dr. Laurel Trufant completed the final and exhaustive edit. Her professional work on the manuscript was extraordinary.

My younger son, Alexander W. Jacobs, gave me sage encouragement. Prof. Young-hae Chi provided helpful suggestions, thus making the manuscript stronger. Leslie Kean, Prof. Don Donderi, and Prof. Ronald Westrum have encouraged me while listening to more detailed expositions of my theories.

My literary agent Lisa Hagan took a chance with me. Greg Brandenburgh, associate publisher at Red Wheel Weiser publications, also took a chance and accepted this unusual book. I am enormously appreciative of their efforts.

I am grateful for the work done by abduction pioneers such as Prof. Leo Sprinkle, Prof. James Harder, Dr. Richard Haines, Ann Druffel, Prof. Karla Turner, and many others who showed that something profoundly unusual was happening and people must take abductions seriously. Prof. John Mack lent intelligence and prestige to the study of this fringe phenomenon. Dr. Roger Leir made important contributions into the physicality of abductions. Hypnotherapists Yvonne Smith, John S. Carpenter, Jed Turnbull, Kathleen Marden, and other colleagues have continued, often in the face of ridicule, to seriously study abductions. All serious abduction researchers are caring people who want to help abductees while researching the phenomenon.

I am profoundly indebted to the abductees with whom I have worked to uncover their experiences. They are heroic souls who allowed me to enter into their private lives; they have astounding courage and determination. This is especially true of “Betsey” who gave me access into her life for a period of time that went well beyond what most people would endure.

Of course, my dear friend Budd Hopkins made all my abduction research possible.

During a hypnosis session in 2003, Bernard Davis told me an absurd story. He said he went to a Baltimore Orioles baseball game with his close friend, Eric. Yet Bernard knew nothing about Eric. He did not know his last name, where he came from, where he lived, what he did for work, or how he had met him. However, he and Eric had been close friends for more than seventeen years. Bernard even showed me a 1995 photograph of Eric—an ordinary-looking man in his thirties sitting with Bernard on a fishing boat in Brazil.

Over the years, abductees have told me about having “special friends” like Eric who befriended them in childhood and continued to visit them for decades onboard an unidentified flying object (UFO) or in strict privacy on Earth.1 But Bernard's relationship with Eric was different. Rather than meeting only onboard or in secret, they spent time together in public. They often met at restaurants; they drove to various places; they met in different countries during Bernard's business trips; they went sightseeing. They also had long talks about how to live in human society. The problem is that Eric is a hybrid—a mixture of alien and human.

Just a few years before, I would have considered Bernard's baseball story pure unconscious fabrication. This type of public human/hybrid interaction did not fit the descriptions I had heard since I began doing abduction research. But soon after Bernard started having sessions with me, other abductees began to give similar accounts of public interactions with hybrids. They were relating something new and alarming. Not only were they engaging in activities with aliens and adult hybrids onboard UFOs; they were also having complex public interactions with late-adolescent and young-adult hybrids who were all focused on one goal—assimilating into human society. Several abductees had their own “Erics.” Bernard's story about attending a baseball game with Eric was consistent with my other findings. My research had uncovered a substantial presence of hybrids living on Earth.

This book tells how I came to this seemingly ridiculous conclusion. It builds upon my previous books and on my fifty years of research in the UFO and abduction field. To have a foundation for processing the information in this book, it may help to have a brief review of my research and other books, which I have given in the appendix. This book will illustrate how hybrid aliens are integrating themselves into human society and their strategies for achieving their goals. The narrative is based on interviews with fourteen abductees—a small fraction of the 1,150 abduction events I have investigated over the years. Their testimony has led me to some surprising conclusions.

My thinking on the subject of alien integration has evolved as my knowledge has widened. I now know enough to theorize about who these beings are and what they are doing. Unfortunately, I still do not know the ultimate reason they are doing it—the “why.” At the end of this book, I provide some possible explanations. But the “why” remains the last great unanswered question in abduction and UFO research.

In this book, I will examine our current and previously unknown knowledge of the abduction phenomenon. Chapter 1 explores the testimony of abductees and how we are able to explore their experiences. Chapter 2 redefines abductions, describes who abductees are, outlines their function within the alien program, discusses alien goals in detail, and begins to delve into the progression of their abduction program. Chapter 3 outlines onboard training and assessment for young hybrids who will eventually integrate into human society. Chapter 4 describes training and assessment for older hybrids. Chapter 5 details hybrid visits into abductees' homes to become familiar with human living. Chapter 6 shows how abductees are helping hybrids move into their apartments and training them in “real life” situations. Chapter 7 identifies the various problems of hybrid adjustment. Chapter 8 discusses how hybrids learn about the complexities of human relationships. Chapter 9 explains how abductees are trained to do aliens' work and thus gives us a glimpse of the future. Chapter 10 speculates about the alien program's meaning. Historians normally do not use conditional words like could, would, should, may, might, and probably, but I will use them throughout the book.

Ultimately, this book is not about abductions. It is about the aliens' program and the niche that abductees have within it. My research into the program has revealed it in greater detail than ever before. Though the aliens themselves are mysterious, nothing about their activities is beyond understanding. And with more evidence, we will learn more. I hope that this book will be a step in that direction.

I understand that alien integration into human society sounds ridiculous. The idea that alien/human hybrids are living on Earth is inherently preposterous. During media interviews, my favorite question has been: Do you think aliens are walking among us? I liked this question because it gave me a chance to say, “Absolutely not! There is no evidence whatsoever that aliens are walking among us.” This answer allowed me to feel sane in the world of presumed craziness in which I dwelled. In this book, however, I give evidence for aliens not only walking among us, but living here as well. By doing so, I realize that I am stepping over a line that most abduction researchers—and especially most UFO researchers—will not cross. But as an academic researcher, I must follow the evidence where it leads.

Still, I feel uneasy about relating what I have found. Believing such incredible testimony seems weak-minded and fodder for supposedly tough-minded debunkers. Writing that an abductee took a hybrid to a baseball game embarrasses me and strengthens the debunkers' resolve. But regardless of my personal discomfort, I am confident of the veracity of the information I present here. Nevertheless, readers should be aware that no author is infallible, and that abductees may not have perfect recall.

In this book, I use edited verbatim transcripts more extensively than I have in the past because they provide compelling first-person accounts. I have pared most of the transcripts down to their essentials, removing tangential conversations between the abductee and me as well as other extraneous utterances. In all cases, I have preserved their exact meaning and context.

In understanding these transcripts' usefulness, it is important to know that when abductees describe their experiences, they often do so at great personal peril. Many abductees are successful, high-functioning individuals with advanced professional degrees who risk their reputations and livelihoods by relating their experiences. Abductees come from all strata of society. Among them are physicians, businesspeople, attorneys, psychologists, psychiatrists, scientists, university professors, graduate students, police officers, librarians, retailers, laborers, retirees, and the unemployed. They all face ridicule and scorn when they claim they were abducted by extraterrestrial beings. One abductee who talked about his experiences in his workplace was fired. Others who told their spouses about their abductions have had the accounts used against them as proof of mental instability in divorce and child-custody proceedings. Very little good can come from relating such experiences to nonabductees. For a person even to have an interest in the subject—without a claim of abduction—can make others question their mental stability. When child abductees talk about their experiences at school, they undergo relentless teasing and learn to keep their memories to themselves. Yet the need for many abductees to understand what has been happening to them outweighs the danger of disclosure. They come to me out of desperation, driven to find a rational explanation for the seemingly irrational activities that have intruded upon their lives.

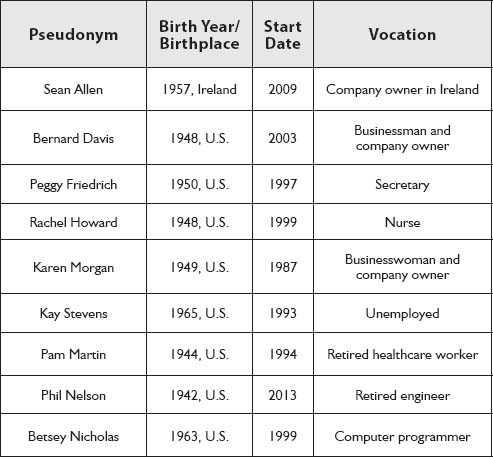

I selected most of the fourteen abductees whose experiences I use in this book because they best elucidate the end-point phase of the abduction program and demonstrate new and chilling aspects of the alien agenda. All the names given here are pseudonyms to maintain confidentiality. Table 1 presents a list of the abductees' false names, their actual birth years and places, the years when I first began to work with them, and their vocations.

TABLE 1: ABDUCTEE PROFILES

I had the most sessions with Betsey. From 1999 to 2007, we examined over 100 abduction events and I had the unprecedented opportunity of having sessions with her on a weekly basis or more for over a year. This access allowed me to delve more deeply into her daily life and discover unknown details of the abduction program. To the best of my knowledge, no other investigator has had such entrée to or opportunity with any abductee. She was an excellent describer of her experiences and I quote her extensively throughout this book.

The raw data of abduction research is human memory retrieved through hypnosis, often administered by amateurs. I am acutely aware of the weaknesses of this methodology. But the alien program is clandestine; few abductees consciously recall their abductions. Because of this, abductees have unique problems in retrieving detailed abduction memories, and abduction researchers rarely understand how to elicit accurate descriptions. Unfortunately, there are currently no courses on abduction hypnosis and no reliable books on the subject. Learning comes from trial, error, and experience. Becoming competent with abduction hypnosis requires a thorough knowledge of the abduction phenomenon and an awareness of the pitfalls of retrieved memory. There are precious few people who are able to do this.

Even with competent hypnosis, abduction descriptions are still controversial. Evidence for the abduction phenomenon is anecdotal and often incomplete. And, as is to be expected with incomplete data, accounts often present more questions than answers. Furthermore, abductees may confabulate—fabricate imaginary experiences as compensation for loss of memory—and relate events that either did not happen (although they think they did) or happened differently from what they remember. In spite of these problems, the consistency of detail and narrative over time has generated an authenticity that cannot be matched by idiosyncratic imaginations. When researchers retrieve abductees' memories competently, they can give us a realistic glimpse into the extraordinary world of alien abductions.

Abduction accounts remembered without the benefit of competent hypnosis are most often untrustworthy, no matter how much abductees are invested in their memories' truthfulness and accuracy. Even with competent hypnosis, confabulation is common in the first few hypnosis sessions and declines in subsequent attempts. Practitioners must learn how to correct for confabulated memories by using a set of controls to recognize and mitigate them. Unfortunately, inexperienced or highly trusting abduction researchers cannot identify confabulation and even encourage it through improper questioning. The result is false accounts that incompetent researchers think are true.

An example of the perils of confabulation is telepathy. Communication among beings onboard UFOs is consistently said to be telepathic. Abductees describe it as the sensing of thoughts. Thus, little prevents them from sensing their own thoughts and thinking that they are communications from aliens. This occurs most frequently in abductees' conscious memories.

Other errors are the direct fault of abduction researchers. Some harbor agendas that they instill in abductees—either subtly or hamfistedly. Though some researchers are sincere believers in abduction phenomena, they tend to be New Age supporters who are dedicated to the idea that aliens are here to bring us into a higher state of consciousness. Aliens will do everything from spiritually enlightening us, to teaching us to heal each other or the Earth, to ending war, to stopping the despoiling of the environment, eliminating weapons of mass destruction, and preparing us to join a welcoming community of planets.

I sometimes come across accounts in which aliens talk of the environment's ruination. But if these memories are accurate—and I now have serious doubts about that—the aliens' concern about the environment is less about saving it for humans and more about on what kind of planet they themselves want to live. This is the argument I make in my book, The Threat.

When I conduct hypnosis with abductees, I use simple relaxation techniques. The subjects are not in a trance. They sometimes tell me that they are not hypnotized, but I often tell them it does not matter. During a hypnosis session, I ask logical and chronological questions that can hardly be considered leading or suggestive. The abductee dictates what I can ask. For example, if abductees say they are on a table and then go into another room, I ask how they got off the table. After they tell me how, I ask if they are standing and what they can see now that they have a different point of view. If they begin to walk, I ask in what direction. If they are headed for a doorway, I ask about the shape of it. If they leave a room, I ask if they go straight ahead or turn left or right. If they say they are in a hallway, I ask about its size and shape, the lighting there, and other particulars.

It is easy to overdo this type of questioning, so I try to keep it within reason. I often leave my questions open-ended so my own opinions do not influence their answers. For new subjects with whom I have had only three or fewer sessions, I try to ask subtly misleading questions to test their suggestibility. I find that people rarely can be dissuaded. After several sessions, once I am familiar with the person and no longer worry about confabulation, I become more conversational rather than interrogative. These simple and logical techniques help prevent confabulation and aid in memory recovery.2

Abduction research consists of uncovering patterns. Without those patterns, all memories would be individualistic and therefore almost certainly self-created. Different psychological phenomena would produce wildly varying abduction accounts. In fact, without patterns, there would be no abduction program to investigate.

Typically, I hear the same abduction accounts over and over. I have heard some specific events in the same detail hundreds of times—some so often that I have to force myself to stay awake. But that soporific, repetitive quality is critically important for verifying accounts. Once in a while, I hear something new, something that potentially can advance my knowledge. I am usually skeptical of these accounts and do not elevate that information to evidence until other abductees without knowledge of the previous testimony report the same thing. I wait for a pattern to emerge. In general, multiple descriptions of the same phenomena are the most important aspect of abduction investigation.

Of course, patterns can be elicited through inept questioning as well. Some researchers using flawed methodology have received multiple descriptions of similar events—for example, receiving messages from aliens. They then claim these events as solid evidence. Usually, these accounts are born from leading questions and/or the bizarre practice of asking abductees to question aliens—as if the abduction were taking place at the moment. This directly calls for confabulation, and subjects unwittingly cooperate. Information from this type of questioning is useless and undermines rigorous abduction research. With competent investigation, abductees say what they know and not what they do not know.

A critical pattern that has persisted over years of rigorous, methodical abduction research is that of reproductive procedures. The pattern emerged with the first two abduction cases discovered—the 1957 Antonio Villas Boas case in Brazil and the 1961 case of Barney and Betty Hill in America. Villas Boas reported having sexual relations with a female being who looked human. After the sexual activity, the female pointed to her abdomen and then up, presumably toward the sky. Villas Boas said he thought he was being used as a “stallion to improve their stock.” No hypnosis was used with Villas Boas.

The Hill case was the first to be investigated through hypnosis, but the hypnotist, though talented and experienced, did not know about abduction phenomena and its attendant memory problems. Barney reported that sperm was taken from him; Betty said an alien pierced her navel with a needle, telling her it was a “pregnancy test.”

The Villas Boas case was not published until 1966, and neither the 1966 book nor the 1975 television movie about the Hill case discussed Barney's sperm sample. Consequently, the cases had little influence on future abduction accounts of reproductive processes. Nevertheless, since the late 1970s, the reproductive aspects of abductions have grown in importance as researchers began to realize their ubiquity. Indeed, the prevalence of reproductive procedures in abductee accounts has led us to understand what renowned abduction researcher Budd Hopkins first uncovered in 1983—that aliens were using human sperm and ova and adding alien biological material to create a mixture of the two species. He called these partially human/partially alien beings “hybrids.”

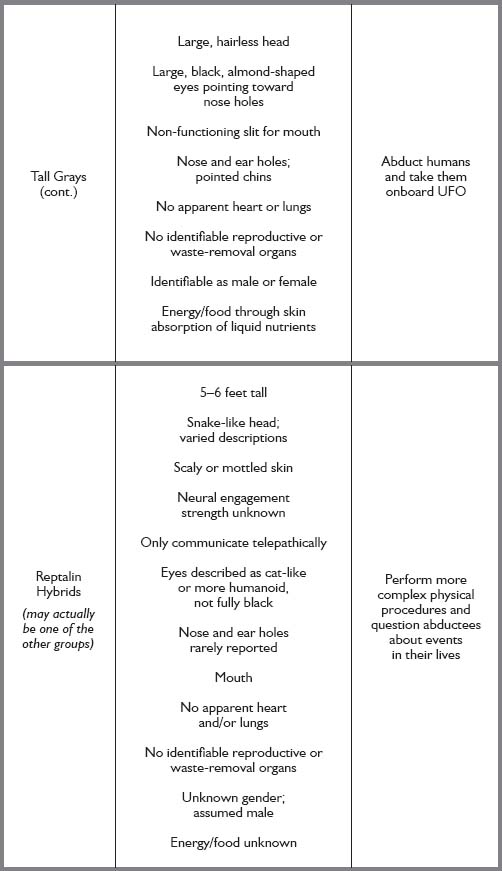

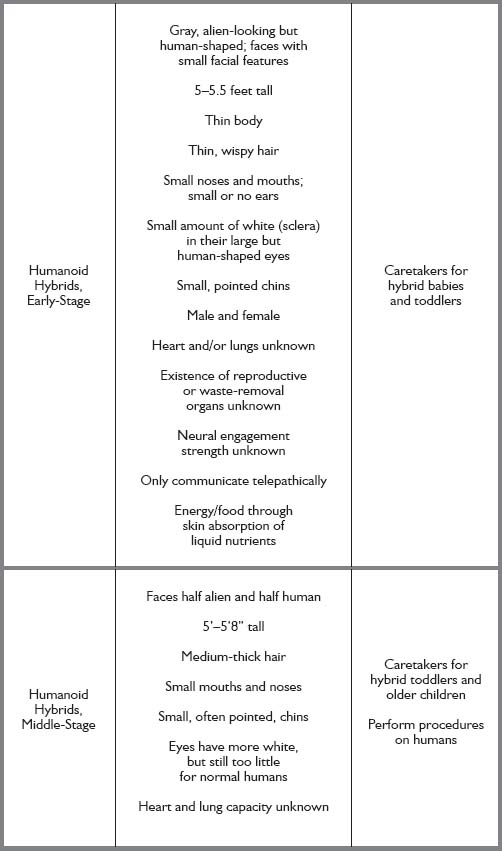

The gestation of these hybrids begins with an insertion procedure. Female abductees report that aliens inserted a hybrid embryo into the uterus and removed a fetus nine to eleven weeks later. During subsequent abduction events, these abductees saw the offspring (although not necessarily their own) as infants, toddlers, adolescents, young adults, and adults. (Oddly, I have heard no reports of abductees seeing hybrids as elderly adults.)

Abductees report a spectrum of hybrid types, from those who look mostly alien to those who look human. Abductees also describe a spectrum of hybrid responsibilities, from escorting abductees into a UFO to conducting full abduction events without the aid of the well-known gray aliens—those with large heads, black eyes, and thin bodies. Many abductees report complex personal relationships with adult hybrids.

Fantasies about aliens and abductions often seep into the popular culture and come out as “truths.” In some instances, certain facets of these fantasies have profoundly affected both the society at large and scientists and academics. For example, the concept of receiving a “message” from aliens was used by the infamous “contactees” of the 1950s who claimed they had met aliens, been taken on trips to Venus and other planets, and been given messages—often about the evils of communism, the atomic bomb, and other current issues of the time. The “message” is still part of flying-saucer lore, but it has never been a legitimate aspect of abduction phenomena. When one learns about abductions, the illogicality of such messages becomes evident.

Similarly, the idea of formal “contact” is squarely based in popular culture. Many people are sure that if aliens ever did “come down,” it would occur in a “take-me-to-your-leader” fashion. Aliens and humans would come together as equals, ideally on the White House lawn, with both sides showing courtesy, consideration, and a desire to teach or inform. Though the idea that aliens would reveal themselves publicly is heavily ingrained in the zeitgeist, it is not found in the abduction phenomenon. Furthermore, the converse of this—that aliens are here to destroy humans and take over the planet—is also a popular-culture staple. Movie producers use this idea because of its drama, horror, and violence. Again, though the abduction phenomenon has insidious aspects, there are no reports of a desire to destroy human civilization. Despite the lack of any data, however, these two conceptions of “first contact” have become powerful in a negative way; they are seen as the only options. And because these scenarios have not happened, the majority of people, including academics and scientists, jump to the conclusion that UFO and abduction phenomena are nonsensical.

Nobel Laureate Kary Mullis provides an excellent example of dismissal due to nonconformity to popular expectations. Australian UFO researcher Bill Chalker quotes Mullis: “Any culture that could conquer the barrier of space-time could have easily conquered the far simpler problems of complex biochemistry and would not need us in the manner described in the grey alien-human ‘hybrid’ agenda theories.” This confident statement has no evidentiary basis and suggests that abductions could not occur because they do not follow what he thinks should happen.3

Mullis's statement also suggests that he knows something about life elsewhere. But if we took all the world's scientists and academics who are not UFO and/or alien-abduction researchers or abductees, and combined all their knowledge about extraterrestrial life, the total amount would be zero. As of this writing, this is an irrefutable statement. We must deal with the facts at hand and not say that the aliens would, could, or should behave in a manner we think is proper. Using popular culture or popular scientific speculation to explain abductions must include a chain of evidence demonstrating how cultural information entered into subjects' minds, which then transmuted it into complex personal abduction narratives. Yet competent investigation of abductions fails to reveal any evidentiary chain from popular culture to abduction reports.

One of the critical aspects of the abduction phenomenon is that abductees all say the same thing about what is happening to them, even though they do not share knowledge of each others' experiences. For example, it would be interesting (albeit trivial) to know where aliens come from. If the abduction phenomenon is psychologically based—and therefore, not real—some abductees would simply invent a home base for the aliens, just as they are imagining everything else. We would then have a variety of origin theories. In fact, abductees seldom describe a “home base,” because the aliens they encounter do not choose to give this information. Nor do aliens ever reveal the ultimate reason for why they are here. If the phenomenon were psychological, we would be given a wealth of reasons.

Knowing how aliens got here matters to scientists. They understand the immense difficulties of our going to other solar systems or galaxies with our technology and conclude that it is unlikely for others to travel here. They assume that we are just an insignificant planet in an ordinary solar system. Therefore, there is no reason for aliens to come here. This line of argument is, of course, nonsense. It does not matter how aliens got here or where they come from. Nor does it matter where the Earth is in the galaxy. The only important question is: Are they here? If the answer to this question is “Yes,” the next most important question is: Why are they here? The anecdotal evidence strongly indicates that they are here; the question “why” is what I am exploring in this book.

Scientists, debunkers, and skeptics have many reasons to ignore or discount the abduction phenomenon. No one disputes that people claim to have been abducted. Thus, the phenomenon is either psychological or experiential—there are no other options. Because the experiential explanation is, for many, too unlikely to consider, debunkers and skeptics put forth myriad psychological explanations for it. They cite faulty hypnosis, false-memory syndrome, sleep paralysis, popular-culture osmosis, sexual abuse in childhood, fears of the new millennium, hysterical contagion, self-hypnosis, the will to believe, myth and folklore, and many more explanations.

I have read over thirty-five different—and, for the most part, mutually exclusive—debunking explanations to account for abduction narratives. All the debunkers have a common mind-set. They do not know the accurate evidence for the phenomenon; they ignore the evidence they do know; they distort the evidence to conform to their explanations. I have found no exceptions to this. Most skeptics fail to realize that competent abduction researchers are also familiar with psychological explanations and have thoroughly examined them. No serious researcher wants to mistake psychological accounts for experiential ones. For debunkers, however, any explanation—no matter how divorced from the evidence, no matter how outlandish—is preferable to the idea that abductions are real.

The abduction phenomenon does not lend itself to facile answers. Here are some aspects of reported abductions that must be accounted for in any explanation:

Of equal importance is how abductees deal with the phenomenon.

There has never been anything like this in human history. In the next chapter, we will explore this unique phenomenon of abductions and how they contribute to the alien program.

Over the years, many people have attempted to define the abduction phenomenon. But the phenomenon has yielded itself to analysis only slowly. Most definitions are inaccurate because they fail to incorporate new information accrued over the years. We now know that abductees need not be physically “kidnapped.” They need not necessarily be subjected to examination-type procedures. And they need not be taken onboard a UFO. So perhaps a correct definition of the phenomenon is: An alien-initiated interaction with a human during which the alien controls a human both physically and cognitively in real time and in any location.

This new definition includes activity outside of the UFO and does not require that abductees be physically kidnapped. It does not rely on examination procedures. It also includes neurological control, which is central to the abduction phenomenon. And it is a physical event that takes place within normal temporal bounds. Before describing those who are abducted and the beings who abduct them, however, we need to look at the salient characteristics of each group.

Abductees are easy to define, but difficult to describe. They are people who, from birth, are subject to being placed under the control of aliens and who forget most or all of their experiences immediately after the event ends. The terminology used to describe them, however, is more troubling than the definition. In fact, I dislike the word “abductee.” It marks the person as “other,” as being in some way different from “normal” people, and as somehow psychologically threatening. Unfortunately, however, I have found no acceptable alternative term. “Abductee” is currently the only word that adequately describes a person's situation, and therefore I use it throughout this book.

Some researchers prefer to use the nondescript word “experiencer,” but this term sidesteps the lifelong psychological trauma and physical events that most abductees endure. “Experiencer” subtly imputes neutrality, passivity, and even pleasantness to the phenomenon. As one abductee said, the word “experiencer” is “all pink and fluffy.” To avoid that connotation, other researchers have used cumbersome phrases like “abduction experiencer” and “abductee-experiencer.” “Contactee” is another term used most often by New Age followers. It recycles the old 1950s label for the long-discredited charlatans who falsely claimed contact with aliens. The word is now often used to suggest that benevolent aliens have singled out someone for special help or education. I have never found this to be the case.

Abductees live normal lives except for their involuntary participation in a lifelong abduction program. They come from around the world and they have no common overt traits that suggest they are being abducted. Abductees appear to be randomly distributed across all demographics. Interestingly, health is rarely a barrier to abduction. People who suffer from cardiac disease, diabetes, cancer, and other serious medical problems are all abducted. They do not report miracle cures, although there are rare cases of young children being cured of serious illnesses and of adults being cured of colds. The aliens are not “healers.” In fact, the only people who are not candidates for abduction seem to be those with significant physical and neurological infirmities that prevent them from doing their duties as part of the abduction program.4

Abductees are as emotionally and mentally stable as nonabductees. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), along with other mental and personality assessments, has shown that abductees do not have personality characteristics that would account for their fantastic personal narratives.5 Of course, some abductees are mentally unstable, just as many nonabductees are. My policy is not to work with these subjects if their instability is apparent in advance. In a few cases, these behavioral issues have manifested after I started my sessions, but I have not used any accounts from these people in my research, even though they were abductees.

The vast majority of the people I have worked with are capable of separating reality and fantasy. Some have been referred by professional therapists who did not know how to handle abduction accounts, but who were confident their clients were not delusional. I have also had investigation sessions with abductees who are psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental-health professionals who were clearly capable of differentiating between reality and fantasy.

A common thread among abductees is that one or both of their parents were abductees. Abductions usually begin in infancy (parents are sometimes abducted with their babies) or early childhood; they continue with varying frequency into old age. This fact leads to the question of population size. How many people are or have been abductees? Most people are unaware that they have experienced abduction events. Instead, they may have had many anomalous experiences—missing hours of time, seeing ghosts, traveling on the astral plane, and other odd events—but they do not link them to abduction activity. The best answer we have to the question of numbers is, of course, speculative. But it is clear that, at the very least, millions of people worldwide have been abducted, and their numbers are growing as the world's population increases.

In 1991, Budd Hopkins, sociologist Ron Westrum, and I worked with the Roper Organization to determine how many people have had abduction-like experiences. Roper interviewed 5,986 randomly selected people across the United States. The poll, with an error rate of 1.4 percent, indicated that at minimum 2 percent—6,000,000—Americans have had experiences with abduction-like characteristics. And that number reflects an exceptionally conservative analysis of the poll.6 Of course, to verify these numbers we would have to investigate each case. However, tens of thousands of people have contacted me and my colleagues detailing their abduction experiences. And each one of them likely represents many more who have not contacted a researcher. Given that the abduction phenomenon is global and people around the world describe similar abduction events, the number of abductees is obviously extremely large.7

Most of the beings who abduct humans live onboard UFOs. While all are physically similar to Homo sapiens, all have mental abilities that are significantly different and unimaginably powerful. They communicate telepathically. Using “neural engagement” (a term I now prefer to my original and more science fiction-like term, “mindscan”), abductors can elicit emotions ranging from fear to hatred to love to sexual response. Most abductees undergo some form of neural engagement almost every time they are abducted. Just as important, all aliens can control human thoughts and behavior from a limited distance, without neural engagement. By gazing into an abductee's eyes from a few inches away, or even touching foreheads, they can lock into the optic nerve and, using it as a conduit, stimulate various neural sites within the brain, causing that person to “see,” or think, or physically do whatever they want. The aliens' extraordinary neurological and telepathic abilities are the most significant difference between them and humans. Without these capabilities, abductions would be extremely risky for them, if not impossible.

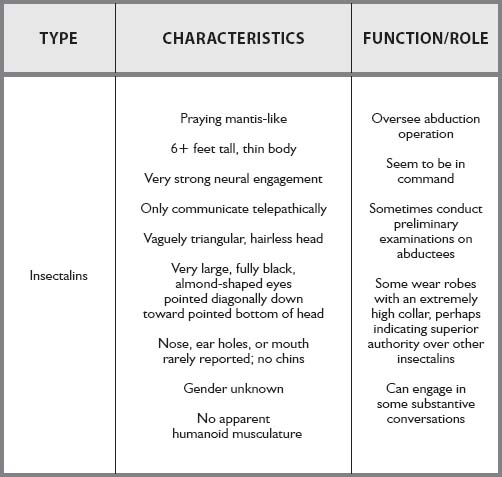

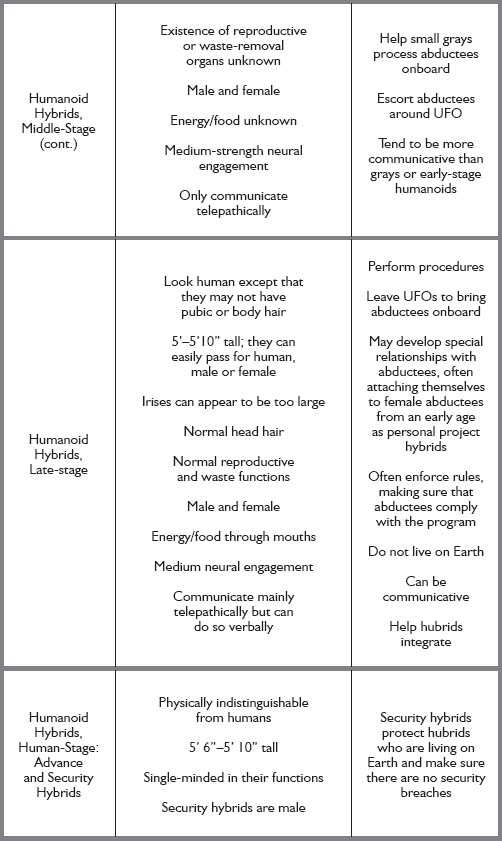

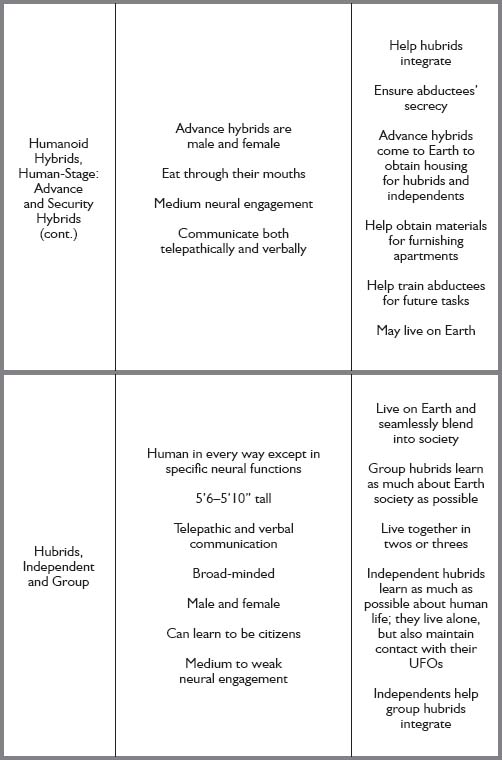

Although aliens and hybrids, whom I will discuss below, share core characteristics, they are not all alike. In my previous books, I described “tall, insect-like beings,” “reptilian-like beings,” and “gray aliens.” As a result of my ongoing research—and at the risk of confusion—I have revised this nomenclature and classification, labeling insect-like beings “insectalins,” reptilian-like beings “reptalins,” and gray aliens simply “grays.” I have also refined the alien/hybrid taxonomy (see Table 2.) All hybrids are still aliens, however, no matter how hybridized they become. Likewise, I previously identified early-stage hybrids (who look very alien-like), middle-stage hybrids (who look half alien and half human), and late-stage hybrids (who look quite human, but with noticeable physical differences).8 To this, I have added different degrees of hybridization based on neurological factors ranging from human-stage, to advance hybrids, to security hybrids, to “hubrids” (hybrids whose function is to assimilate into humanity).9

I hope the new classification places the abduction phenomenon in a more coherent light. Table 2 provides a summary of the physical appearance, characteristics, and functions for the various types of alien beings, although much of what they do is still unknown. A few words of caution: I have separated the aliens into discreet categories. As with all classifications, however, it is certain the hybrids represent a smoother continuum of alien life than can be communicated with this reductive analysis.

I have also rethought the aliens' origins based on their physical appearance and activities. My new hypothesis is that the insectalins are either the “original” aliens, or the least hybridized. Their morphology is the least humanoid and therefore the most alien. I contend, therefore, that they hybridized all the other aliens onboard a UFO, with the possible exception of the reptalins. In the process of hybridization, I include cloning, especially for grays. The evidence for this may be slim, but the inclusion answers questions that have heretofore been inexplicable. With the possible exception of the insectalins and reptalins, all other aliens onboard are hybrids.

TABLE 2: THE ALIEN SPECTRUM

Most aliens and hybrids perform tasks for which they have been created and do not appear to think past their own particular functions. Dissatisfaction with their position is highly unlikely. They are willing functionaries in a complex system. The exception may be the hubrids living on Earth. Their full relationship to onboard aliens is unknown.

Aliens do not have individual names; these are apparently unnecessary in their telepathic society. Thus, abductees give humanoid hybrids names. Because of this, each one may have many names. The absence of a name reflects the aliens' adherence to a group ethic (the collective) and their lack of personal identity and independence within the group.10 Each group of aliens as classified in Table 2 has specific functions for which it was created. The only exception is the insectalins.

Insectalins appear to be the ones in command. They seem superior in intellect and in breadth of understanding. They do not have the well-ordered routine by which grays abide, and therefore they are less structured. They do not perform commonplace tasks, like physically taking humans into a UFO or guiding them through the corridors into rooms. They sometimes conduct preliminary examinations on abductees, although these procedures are generally left to the grays. They employ neural engagement, and abductees report that they perform the most penetrating and strongest neural engagement of all aliens. They appear to have more knowledge of the program than other aliens.

Abductees report that some insectalins wear robes or cloaks with extremely high collars that rise above where ears would be on humans. Researchers do not understand the role of these robe-wearing insectalins, and abductees almost never describe them as involved with common abduction procedures. It is possible that they have a higher status than other insectalins, but more research is needed to understand their function.

Insectalins are supremely logical and appear to lack a humanlike emotional life. Abductees' descriptions of their personalities and communication patterns indicate that they care little about human civilization. To them, humans are an inferior species who are almost childlike in their ability to think and whom they can manipulate, not only individually, but societally as well.

Insectalins appear to have no sense of human morality or ethics, although they may have their own characteristic morality. For them, abducting people is a logical means to an end. Thus, their ability to think rationally is similar to that of humans, whose history is replete with grand-scale attempts to exploit other humans who are considered inferior. In the insectalins' minds, we are the inferior ones ripe for exploitation.

Insectalins are often more apt to communicate with humans than are other aliens. When they have a discussion, it is primarily about their program. I have not yet had a case in which an abductee asked questions about insectalins' personal lives, their non-UFO society, or life on their home venue. Insectalins will sometimes talk about the future, but we cannot be sure that they are telling the full story; they are careful not to divulge too much. Why they talk to people at all is unclear, other than that they may find it diverting to discover a human with the unusual ability to ask questions during an abduction.

Insectalins care little about the people whom they use to create hybrids. They express no guilt or regret about their disruption of human lives. They have little or no sense of humor, pity, or sorrow. They do, however, express a strong entitlement to do whatever they want to humans. They appear not to understand human emotions and therefore they cannot empathize. Whether they have sympathy is unknown, but they and other aliens will stop pain if an abductee is in distress during a physical procedure. However, this may only be to suppress an adrenaline rush that could cause an abductee to become uncontrolled.

I contend that the hybridization of aliens with humans—and perhaps other aliens—is the key to understanding the abduction phenomenon. This is a controversial hypothesis within an already controversial subject, but I will present information in this book that will add substance to my contention.

All hybrids are created to perform specific functions. They all work constantly. Most do not sleep as long as humans do, but humanoid hybrids, and perhaps even grays, go into short sleeplike states. They all have the same neurological abilities in varying degrees of strength. They all communicate telepathically. They all give complete allegiance to insectalins. As hybrids become more human, we can see a progression of human features that the grays do not seem to need.

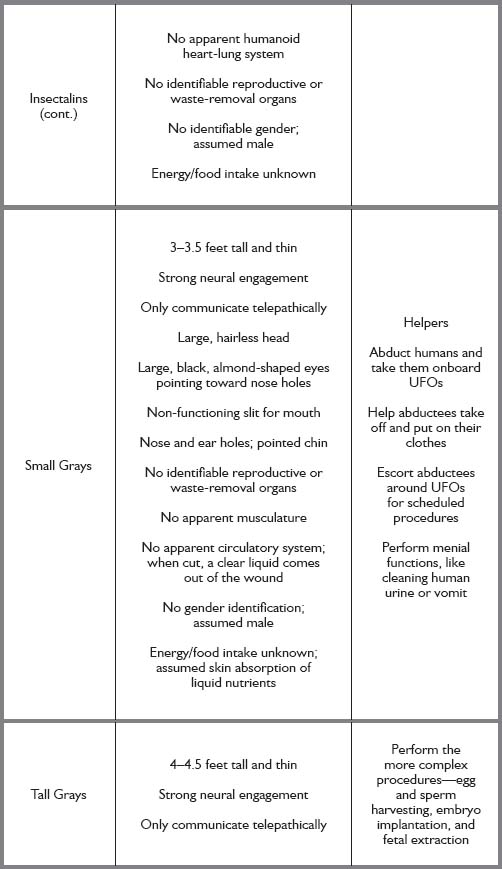

Grays have had the most exposure in popular culture. They have been used to epitomize the “standard alien” in the advertising and entertainment industries since the 1980s. It is difficult to categorize grays in terms of degree of hybridization. The best way to differentiate them is by height and function (see Table 2).

Small grays are basically helpers. They are the ones who come down to Earth to abduct humans and take them to the UFOs. Onboard, they help abductees remove their clothes and then escort them around the UFO for scheduled procedures. When the abduction is almost over, they give the abductees back their clothes and, depending on their mental condition, help them get dressed. They often accompany abductees back to their normal environment. Small grays all wear extremely tight-fitting, almost skin-like clothes.

Tall grays perform more complex procedures on abductees—egg-and-sperm harvesting, embryo implantation, fetal extraction, and neurological engagement. They are the main agents in abduction processes for most abductees. Both small and tall grays have noses and mouths, although they do not eat or talk through their mouths. They have no teeth and no apparent lungs. They do not breathe.

Abductees describe gender differences among grays—some are described as more “graceful” or “seem feminine,” and are therefore thought to be female. Most, however, are apparently not graceful, nor do they exude femininity. These grays are assumed to be male. Tall gray males can be substantively communicative, but most of the time they engage in minimal communication with abductees.