Prologue

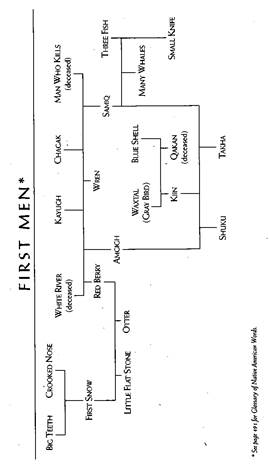

The First Men

The Whale Hunters

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part Two

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Part Three

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Chapter 97

Chapter 98

Chapter 99

Chapter 100

Epilogue

Author’s Notes

Glossary of Native American Words

Image Gallery

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Again, for Neil And for our sisters and brothers

Herendeen Bay, the Alaska Peninsula

KIIN PUT AWAY HER CARVING TOOLS. The gray light of early morning squeezed through the smokehole and met the glow of the seal oil lamp.

Sometime during the night, a mist had begun to fall. It had soaked through the skin walls and mats of their shelter into their sleeping robes and clothing until Kiin thought she would never get its chill out of her bones.

We are safe here, my babies and I, Kiin thought. But the cold that enveloped her body came from more than the rain. I should not have let my husband bring me here. My babies and I were safer in the village with our people than we are in this tiny shelter with Three Fish. Even if traders have come to our people looking for wives, they will not bother me.

“No, stay here,” Kiin’s spirit voice said. “You are wife. You must do what your husband tells you to do. Stay here with Three Fish until Amgigh comes for you.”

Kiin took a long breath, but still could not rid herself of the heaviness that seemed to settle over her. She looked across the sodden sleeping robes at Three Fish. The woman was just waking up. She smiled at Kiin, showing the broken corners of her front teeth.

“I am hungry,” Three Fish said. “We should go out and get food.” Her voice was heavy with the accent of her people, the Whale Hunters. “I know where there are crowberries.”

“It is too soon. The berries will not be ripe yet,” Kiin said.

Three Fish shrugged. “Then we will gather crowberry stems for medicine,” she said.

“Yes, good,” said Kiin. “We can go now.”

But Three Fish made no move toward the door flap. “There was a trader looking for medicine for his eyes,” she said. “If I make crowberry stem medicine, he might trade meat or oil for it.”

“Yes,” said Kiin, “you could do that. We can go now.”

But Three Fish continued talking, telling Kiin about the medicines her mother used to make from fireweed and ugyuun root, and about the bitterroot bulbs that grew so well on the Whale Hunters’ island.

As she listened, a tightness grew in Kiin’s throat. This woman is Samiq’s wife, Kiin thought. This woman has been in Samiq’s arms, has shared Samiq’s sleeping place.

But Kiin’s inside spirit voice whispered: “You had the joy of Samiq for one night. Be glad for that.”

And I have Takha, Kiin thought. Because of that night I have Takha, this son who looks so much like his father. She laid her hands against the bulge under her fur suk where Takha lay, held against her chest by his carrying strap. She moved her hand to her other son—Shuku, twin to Takha—also strapped to her chest.

“But remember,” Kiin’s spirit voice whispered. “Amgigh is your husband.”

Yes, Kiin thought. Amgigh. He is a good husband. What woman could want better? And Amgigh gave me Shuku. Who, seeing Shuku, could doubt he was Amgigh’s son?

“Amgigh also gave you the night you spent with Samiq,” Kiin’s spirit voice reminded her. “It was his choice to share you with his brother.”

“I am glad to be Amgigh’s wife,” Kiin said. “You know that.”

But her spirit answered, “Who can explain the difference between something chosen by the mind and something decided by the heart? Words are not kelp string. They cannot bind pain into neat packs to be stored away like food in a cache.”

Kiin wrapped her arms around her upraised knees, cradling Takha and Shuku between her chest and legs. Three Fish was still talking, her words as steady as the wind. Kiin closed her eyes and tried to think of something other than husbands and babies, something besides the rain and Three Fish’s loud voice. But the thoughts that came to her were again worrying thoughts, and a strange unrest beset her feet and hands.

“It is this shelter,” her spirit voice whispered. “The walls are too close. The oil lamp light is too dim. Turn your mind toward sky and sea, toward high mountains and long grass.”

Then there was a pause in Three Fish’s talking, and Kiin realized that the woman had asked her a question. Did Kiin like to sew birdskins more than sealskins?

What did it matter, birdskins or sealskins? Kiin thought, but she said, “Birdskins.”

“Birdskins?” Three Fish said. “But they tear so easily and it takes so many to make one suk.”

“Yes, you are right,” Kiin answered, but wished Three Fish would stop talking. Kiin pulled Takha from his carrying strap. Maybe if Three Fish were holding him, she would be quiet.

Kiin wrapped the baby in one of the few dry furs from her bed and handed him to Three Fish. He opened his eyes, looked solemnly at Kiin, then turned his head toward Three Fish and smiled. Three Fish laughed and again began to babble, this time to the baby.

Kiin sighed and looked down inside her suk at Shuku. He was asleep. Suddenly she heard what Three Fish was saying to Takha: “Your father will fight and you will be safe. Do not worry. He is strong.”

Kiin pushed herself across the bedding to Three Fish and clasped the woman by both arms. “What did you say?” Kiin asked.

“Only what Amgigh told me, that we must stay here because there are men on the beach who want to trade for women.”

Kiin’s heart moved up to pound at the base of her throat. “And Amgigh will fight them?” she asked Three Fish.

Three Fish pulled away from Kiin’s hands and scooted back against the damp wall of their shelter. “He said he might,” she answered. “All I know is that I saw one of them. A man with a black blanket over his shoulders. Even his face was black. I think Samiq and Amgigh were afraid he would want us.”

“The Raven,” Kiin said. “My brother Qakan sold me to him. I was his wife at the Walrus People’s village. He has come to take me back.” Her voice cracked, and the sound was like a scattering of words broken away from a mourning song.

Three Fish stared at her as though she did not understand what Kiin had said.

“Amgigh cannot win a fight against him,” Kiin whispered. The Raven was too strong, too cunning.

Amgigh would die unless Kiin went with the Raven, and if she went back with the Raven, back to the Walrus People, what would happen to her sons? One would die. Woman of the Sky and Woman of the Sun, those two old ones—the Grandmother and the Aunt—they would tell the whole village about the curse.

“No child can bring death to a village,” Kiin’s spirit voice said, and the voice no longer whispered, but spoke in anger. “Woman of the Sun and Woman of the Sky know nothing but fear.”

My sons are good, Kiin thought. They carry no curse, but because they are twins and because my brother Qakan used me as wife when they were in my womb, the Walrus People think they are cursed. How can I protect two babies against a whole village?

Kiin pressed her lips together and looked at Three Fish, but Three Fish was still talking to Takha, her face close to Takha’s face, both woman and child smiling.

Kiin watched them, and an ache began to build at the center of her chest. She lifted her thoughts to the wind spirits, to the spirits of the mountains that protected the Traders’ Beach. I will be content to be Amgigh’s wife, she told them. Just let him live. She clasped the amulet at her neck. If he is safe and my sons are safe, she thought, I will ask nothing more.

She crawled over to sit beside Three Fish and said, “Our husbands Amgigh and Samiq are brothers, just as my babies Takha and Shuku are brothers.”

Though Kiin wanted to hurry, she forced her words out slowly, gently, so Three Fish would understand. “Our husbands are brothers, so we are sisters.”

“Yes,” said Three Fish.

“I have to go to the beach now, Three Fish,” said Kiin, “but you should stay here with Takha. Keep him from crying as long as you can. If he sleeps, that is good. But finally when he is crying so hard you cannot stop him, then take him to Samiq’s sister Red Berry. She has milk. She will feed him.”

Then Kiin untied the string of babiche that held the carving Samiq’s mother Chagak had given Kiin and handed it to Three Fish.

“A gift for you,” Kiin said. Three Fish cupped the carving of man, woman, and child in her hand.

“Samiq told me about this,” Three Fish said. “The great shaman Shuganan made it. I cannot take it.”

But Kiin said, “You must. We are sisters. You cannot refuse my gift. The one who wears the carving receives the gift of being a good mother.”

For a moment Three Fish sat very still, then she tied the string of babiche around her neck. She clasped the carving tightly in both hands.

Kiin unwrapped the walrus tusk ikyak that she had carved during the long night when sleep would not come. After she had finished carving it, she had cut the ikyak crosswise into two pieces. Had not Woman of the Sun said that Kiin’s sons, being twins, shared one spirit and so must live as one man? Had not Woman of the Sky told Kiin that Shuku and Takha must share one ikyak, one lodge, one wife? Someday, Kiin would make carvings of a lodge and a woman also, and split each, giving one half to each son. With her carvings, they could live without the curse of being twins, each one building his own life as a man.

She hung the ikyak halves on braided sinew cords, fastened one cord around Takha’s neck, the other around Shuku’s.

“This is my blessing to my sons,” she said to Three Fish.

Takha clasped the ikyak and lifted it to his mouth. Shuku slept.

For a moment Kiin watched her sons, then she turned away to roll up her sleeping skins.

“Why are you going to the beach?” Three Fish asked as Kiin worked. “Amgigh told us to stay here.”

“I must go,” Kiin said. Again she sat down beside Three Fish. She reached out to stroke Takha’s cheek. The baby turned his face toward her hand, opened his mouth. “While I am away, you must be mother to Takha,” Kiin told Three Fish. “He is son to Amgigh, but also to Samiq. See,” she said, gathering Takha’s hand into her own, spreading her son’s fingers, “he has Samiq’s wide hands.” She brushed the top of his head. “He has Samiq’s thick hair.”

Three Fish lifted the baby and laid him against her chest, tucking his head up under her chin. “I will be a good mother to him,” she said.

Kiin looked away, then leaned forward to pick up her carving tools. She slipped them into her sleeping furs, strapped the bundle to her back, then crawled to the door flap.

“Be sure Red Berry feeds him,” Kiin said. Then, though she had not meant to go back, Kiin turned. She held her hands out toward Takha.

Three Fish handed Kiin the baby, and Kiin lifted him from his fur wrappings. She stroked her hands down his fat legs and arms, over his soft belly. She pressed him against her face, smelled the good oil smell of his skin. Then she handed him back to Three Fish and slipped out of the shelter into the rain.

“I will see my son again tonight,” Kiin said to the wind and waited for an answer, but there was nothing. No answer, no whisper to pull away her doubts.

Kiin stroked the carving that hung at her waist, the whale tooth she had made into a shell—her first carving, a sign of the gift the spirits had given her. Then she tucked her arms around Shuku, alone in his carrying strap under her suk, and walked toward the beach.

Yunaska Island, the Aleutian Chain

FOUR HUNTERS’ IKYAN HAD LEFT THE BEACH. Three returned. Kukutux, eyes gifted to see beyond what others saw, blinked once, twice, and looked again. Only three.

She glanced at the other Whale Hunter women around her, saw their grim faces.

“You see them, Kukutux?” Speckled Basket asked. The woman leaned against the stick her husband had carved, which allowed her to walk in spite of a foot crushed last spring when the mountains destroyed the Whale Hunter village.

“I see ikyan,” Kukutux said slowly, her words heavy with the weight of her fear.

“How many?” asked Fish Eater’s third wife, a young woman, too young to belong to the one-eyed Fish Eater, a man nearly too old to hunt.

Kukutux shook her head, lifted her shoulders in a shrug. She had seen hunters return before, knew that the ikyan seemed to lift themselves over the horizon, as though the sea curved down under the weight of the ice that bordered that far edge of the earth. Sometimes when she sighted only one or two ikyan, others would suddenly appear—thin dark lines coming up from the water, as though they had been visiting those undersea villages owned by seal and whale.

She waited, saying nothing, until some of the other women began to point, able themselves to see the first of the three ikyan coming back toward the Whale Hunter beach. “Kukutux,” Flowers-in-her-hair said, “how many? Do they bring a whale?”

“No,” Kukutux answered. “No whale.”

“How many?” asked Speckled Basket, her voice whining with anxiety.

“Three,” Kukutux finally said, and suddenly felt the need for tears, as though the word made true what her eyes had known. “Only three.”

Several women raised their voices in a thin, high mourning chant, but Old Goose Woman hushed them, hissing that their mourning would call spirits. Who could say, she told them, perhaps the last hunter was coming still, towing seal or sea lion, the animal buoyed with breath-filled sealskins. Who could say? Perhaps there would be meat and oil for everyone tonight. Why curse a blessing? Had not those mountains—Aka and Okmok—brought enough curses to the Whale Hunters? Did the women themselves need to add to the curse of fire and ash and darkness?

And though Kukutux clung to Old Goose Woman’s words of hope, fixing her eyes on the woman’s thin and matted hair, the dark and grease-stained fur of her ankle-length suk, she heard the mourning chant in her head as though the women still sang it.

It is for your son, Kukutux told herself. The mourning chant is for your son, that strong, dark-haired baby, gone now three moons, his breath stolen by the mountain’s ash that still covers the beach and the hills behind the village. You mourn him. The chant is for him. The spirits would not take another of the Whale Hunter men. They would not. Too many men have died, in hunt after hunt. How can the village survive if more men die? The mountain has taken enough. And this spring, the whales did not come. Even the beach geese—those winter-breaking birds, their voices loud enough to scare away the snow—have passed the Whale Hunters’ island, the geese flying so high that the women’s bird nets, the men’s bird spears, could not hope to take them.

Kukutux scraped at the beach gravel with her feet and did not let herself look at the sea. Perhaps her own eyes were the curse. Perhaps if she did not look, the fourth ikyak would appear. But then she heard the women’s voices lift in questions, their words edged with the hard sharpness of fear, and she could not keep her eyes from looking.

Finally Old Goose Woman said, “Tell us, Kukutux. It is better to know than to be caught between hope and fear.”

So Kukutux said, “There are three, only three, and the first two ikyan are tied together. Something lies over their decks.”

“A seal?” Speckled Basket asked and reached up to clasp a strand of her hair taken by the wind.

“A man,” Kukutux said. Then the ikyan drew near, and she felt all strength leave her knees so that they folded and let her drop to the ground.

“Who?” came a woman’s voice, then another, all calling her, as though they did not notice she had fallen. The words, like sharp-nailed fingers, picked at her suk, her hair, her skin, until Kukutux closed her eyes, cursed their far-seeing in her heart, and whispered the name: “White Stone.”

She tried to begin a mourning chant, tried but could not remember the words. The women’s voices were only a rush in her ears, like wind roaring; and lifted above all other sounds was her own voice crying out, “White Stone, my husband, my husband White Stone.”

Herendeen Bay, the Alaska Peninsula

KIIN PUSHED HER WAY through the circle of men gathered on the beach. When she reached open ground, she saw the Raven. His chest was bare, his skin glazed with sweat, flecked with blood. He lifted a long-bladed obsidian knife as though to greet her. It was Amgigh’s knife, one Amgigh had made, and the blade dripped blood.

The Raven sucked in his cheeks, let the lids of his eyes nearly close. “Your carvings, wife,” he said. “They gave me power.”

He pointed, and Kiin looked back at the edge of open ground, where a line of her carvings divided those men who watched from those who fought. The carvings were the ones she had made and traded for meat and oil so the First Men could live through the winter.

“Where …” she began, then shook her head and said to the Raven, “I am not your wife.”

The Raven snorted. “Go then to him.” He raised the knife, used it to point, and Kiin let herself look where she did not want to look, let her eyes see what she did not want to see: Amgigh lying in the sand, Samiq kneeling beside him. Then Kiin, too, was beside Amgigh, her arms over Amgigh’s chest, her hair turning red with Amgigh’s blood. She clasped her amulet, rubbed it over Amgigh’s forehead, over his cheeks.

“Do not die, Amgigh,” she whispered. “Do not die, oh Amgigh. Do not die.”

Amgigh took one long breath, tried to speak, but his words were lost in the blood that bubbled from his mouth. He took another breath, choked. Then his eyes rolled back, widened to release his spirit. Kiin moved to cradle Amgigh’s head in her arms, and began the soft words of a song, something that came to her as she held him, something that asked spirits to act, something that begged her husband’s forgiveness, that cursed the animals she had carved.

When the song was finished, Kiin stood, wiped one hand over her eyes. “I should have come sooner,” she said. “I should have known he would fight the Raven. It is my fault. I …”

But Samiq came to her, pressed his fingers against her lips. “You could not have stopped him,” he said. “You are my wife now. I will not let Raven take you.”

Kiin looked into Samiq’s eyes, saw how much of him was still a boy, and how little he knew about the kind of fighting that had nothing to do with knives. “No, Samiq,” she said. “You do not have the power to kill him.”

Samiq’s jaw tightened, he shook his head. “A knife,” he said and turned to the men gathered around him.

Someone handed him a knife, poorly made, the edge blunt, but Samiq grabbed it.

The Raven clenched his teeth, screamed in the Walrus tongue, “You, a boy, will fight me? You, a child? You learned nothing from that one there, that dead boy in the sand?”

“The Raven does not want to fight you,” Kiin said, her breath coming in sobs. “Samiq, please. You are not strong enough. He will kill you.”

But Samiq pushed Kiin aside, lunged forward, wrist cocked with the longest edge of the blade toward the Raven. The Raven crouched, and Kiin could hear him mumbling—shaman’s words, chants and curses, prayers to the carvings she had made. She ran to her carved animals, knelt among them, heaped sand over them.

She looked up, saw Samiq slash his knife in an arc toward the Raven. The blade caught the back of the Raven’s hand, ripped the skin open, drew blood. But the Raven did not move.

“Kiin,” the Raven called out, “this man, he is your ‘Yellow-hair,’ is he not?”

And Kiin, remembering the Raven’s love for his dead wife Yellow-hair, said, “Do not kill him. I will be your wife, only please do not kill him.”

The Raven moved, his movement like the dark blur of a bird flying. The long blade of his knife bit into Samiq’s flesh, into the place where wrist joins hand. Then Kiin was running across the sand, through blood from the first fight, to stand between Samiq and the Raven. Small Knife, Samiq’s adopted son, was there also, gripping Samiq’s arms.

“You cannot win,” Small Knife said. “Look at your hand.”

Samiq glanced down, but said, “I have to fight. I cannot let him take Kiin.”

“Do not fight,” Kiin said. “You have Small Knife. He is your son now. You have Three Fish. She is a good wife. Someday you will have the power to fight the Raven and win. Until then I will stay with him. I am not strong enough to stand against him, but I am strong enough to wait for you. I have lived in the Walrus village this past year. They are good people. Come for me when you are ready.”

Then Ice Hunter, a man from the Walrus village, was beside Kiin. He reached for Samiq’s arm, wrapped a strip of seal hide around the wound, pulled it tight to stop the blood. “You have no reason to fight,” Ice Hunter said. “The first fight was fair. The spirits decided.”

Kiin looked into Samiq’s eyes, saw the emptiness of his defeat. She pulled off the shell bead necklace he had given her the night of her woman’s ceremony. Slowly she placed it over Samiq’s head. “Someday you will fight him,” she said. “You will fight him, and then you will give this necklace back to me.”

She turned to the Raven. “If I am to go with you, I must go now,” she said, and she spoke in the First Men’s language, then repeated the words in the Walrus tongue.

“Where are our sons?” the Raven asked.

“Shuku is here,” Kiin answered, and raised her suk so he could see the child. “But I gave Takha to the wind spirits as the Grandmother and the Aunt said I must.” Kiin took Shuku from his carrying sling. “This is your son,” she said to the Raven, “but he is no longer Shuku. He is Amgigh.”

Kiin saw the Raven’s anger, the clouding of the Raven’s eyes, but she did not look away, did not flinch, even when he raised his hand as though to strike her.

“Hit me,” Kiin said to the Raven. “Show these people that a shaman has only the power of anger against his wife, the power of his hands, the power of his knife.” She dropped her voice to a whisper. “A man does not need a strong spirit when he has a large knife, a knife stolen from someone else.”

The Raven threw the obsidian knife to the ground. Kiin picked it up, walked back to Samiq, placed it in his left hand. Her eyes met Samiq’s eyes. “Always,” she said, “I am your wife.”

The Raven gestured toward Ice Hunter, toward the other Walrus men who had come with him. One picked up Kiin’s carvings, another brought the Raven’s ik to the water.

“We will not return to this beach,” the Raven said.

But Kiin bent down and picked up a handful of pebbles from the sand. She waited as her mother brought Shuku’s cradle and a bundle of Kiin’s belongings from the ulaq.

Once more Kiin looked at Samiq, tried to press the image of his face into her mind, then she turned and followed the Raven to his ik.

The Bering Sea

SHE HEARD NOTHING. NOT the full round voice of the wind nor the high, curling cries of oyster catcher and gull, not the dip and splash of paddles nor the soft throat purr of Shuku nursing. But the silence was as sharp as obsidian, as dark as old blood. Even Kiin’s spirit was still, so quiet that if she had not felt its ache in her chest, she would have believed it was gone—passed on to Three Fish along with the gift of Kiin’s son Takha, along with that carving of man, woman, and child made long ago by the great shaman Shuganan.

She had not offered to paddle, nor had she looked back at the Raven, nor at the ikyan that skirted the Raven’s trading ik.

Kiin pulled herself away from what her eyes were seeing, what her ears were hearing, until there was nothing but the throb of her spirit, pulsing like a wound. At first, its rhythm was the sound of her loss: Amgigh, Takha, Samiq; Amgigh, Takha, Samiq. But now there was silence, and Kiin wondered if she and the Raven and the Walrus People traders were no longer a part of the seen world, but instead had paddled into some world of story or song. Perhaps even now they were carried in the mind of a storyteller, alive only when words fell from the storyteller’s mouth into the ears of those who listened.

When the Raven finally spoke, Kiin did not hear him, but instead, in a rush as harsh as storm wind, heard the noise of the sea. Then she felt the cold of spray against her cheeks, and she knew the choice she had made was not merely a story to be told on winter nights, but something so real that it could separate her mind from her spirit until the emptiness was complete.

So as the Raven called to his men, pointing with his paddle toward an inlet that broke the gray line of the shore, Kiin called to her spirit, until she heard the thin whispers of her spirit voice, its first word, a name—“Takha.”

And Kiin answered, “No, Shuku.”

Then the Raven’s ik touched shore, and Kiin, arms careful of Shuku asleep in his carrying sling under her suk, leaped ashore. She gathered driftwood and watched as the men made a beach fire, and when Ice Hunter handed out pieces of dried fish, Kiin did not ask or wait, but took fish as though she were one of the traders.

Ice Hunter did not speak, but raised eyebrows at her, so that Kiin, biting into the firm, smoky meat, said, “I carve,” and before he passed on to another, she reached out for a second piece.

They used the ik for shelter, tipping it to lie with its broad bottom toward the wind. The Raven hung the rectangle of wood that was Shuku’s cradle from the ik ribs, then motioned for Kiin to pull off her suk. Kiin looked hard into the Raven’s eyes and did as he asked, but she did not put Shuku into his cradle. He would be warmer strapped against her chest.

The Raven pulled off his parka and pushed Kiin into the shelter of the ik’s bow. Kiin turned so her face was toward the ik, her back to the Raven. He lay down beside her, draped his feather cape over them, and pressed his body against hers.

Kiin waited, her flesh prickling with the touch of his skin. She laid one hand over Shuku, the other against her belly, and remembered when she had carried both her sons warm and safe under her heart. Then she felt the push of the Raven’s man part, hard against her back, and she lay very still, scarcely allowing herself to breathe. But he did not try to enter her, to claim her as wife. Finally, he relaxed, his arm heavy against her ribs, and the rhythm of his breathing smoothed into sleep.

The Raven’s warmth softened the darkness, until the night, like fingers weaving, twined dreams into Kiin’s thoughts. But then Kiin’s spirit spoke, jerking her awake with a voice as shrill as an oyster catcher’s cry. “Amgigh, Amgigh, Amgigh.” A mourning song.

Kiin let the sorrow fill her until it pushed tears from her eyes. Once again, she saw Amgigh dead on the beach, but she also pictured Samiq, Takha in his arms, the two safe with Three Fish in the shelter of Samiq’s ulaq.

Kiin took a long breath and wiped her cheeks with the back of her hand. “I am strong,” she told her spirit. “They are safe, and I am strong.”

Turning her head in the direction of the Traders’ Beach, where the mound of Samiq’s ulaq rose from the earth, she whispered the same words to the night wind.

Who could say? Perhaps the wind would carry the words to Samiq. Perhaps someday it would bring his words to her.

KIIN GUIDED HER SON’S HEAD to her breast. He drew the nipple into his mouth and sucked, bringing a twinge of pain and then the release of milk. Shuku’s body relaxed against her own.

Though she had awakened to the words of a mourning song, Kiin had held those words within until she and the Raven had launched the ik. Now the song filled her mouth and she sang. She rocked, and her rocking joined the rhythm of the Raven’s paddle, the swell of waves.

“I hope you mourn our son,” the Raven called to her.

A sharp thrust of anger pierced Kiin’s pain, and she turned to face him.

“You would tell me to mourn?” she said, spitting the words out toward the man. “You would have allowed two old women to kill our sons. You tell me to mourn?”

The hood of the Raven’s chigadax covered his dark hair, and the wooden visor he wore against the glare and spray of water shaded his eyes, but Kiin saw the tight working of his jaw.

“Our son Takha is dead,” the Raven said. “You were the one who gave him to the wind spirits!”

Kiin clamped her teeth together to hold in her words.

“Why did you go with your brother?” the Raven asked. “He stole you from your father. He tried to sell you as slave. Why trust him after he had done those things to you? I told you I would let you go back to your First Men husband if you left Shuku and Takha with me. Instead you chose to kill Takha. Now you have lost both son and husband. Did you also help your brother kill my Yellow-hair?”

Kiin’s anger filled the emptiness left by her grief. “You were going to kill my sons. You had chosen to believe the Grandmother and the Aunt. You had decided your power could not stand against their curse. You are no shaman!”

“You fool, Kiin!” the Raven hissed. “Why would I kill our sons? I am a shaman. I need their power.”

“See!” Kiin said, her arms tightening around Shuku. “You do not care about them except for yourself, for your own power. When the Grandmother and the Aunt made you believe my children could bring a curse to your lodge …”

“Who told you I would kill our sons?”

“My brother Qakan.”

The Raven’s face twisted. “When did Qakan ever speak the truth?” he snarled. “If a man uses his sister like a wife, can he do anything but lie?”

The Raven’s words moved over Kiin like the dense wetness of fog. So the Raven knew about Qakan, knew that Qakan had forced himself on her. Perhaps that was why he had never taken Kiin into his bed even though he called her wife.

Kiin pressed her hands into tight fists. “He told the truth to save his sons,” she said. Her words were quiet, so that the Raven leaned forward, and for a moment stopped paddling.

“He believed the babies were his?”

“Yes.”

The Raven dug his paddle down into the water and for a long time did not speak.

Finally Kiin said, “I did not know Qakan killed Yellow-hair. I did not know she was dead until I saw you and Qakan fighting on the beach, until I heard you accuse him as he died.”

“You were there on that beach?” the Raven asked.

Grief closed Kiin’s throat. If the Raven had found her, he would have taken her back to the Walrus People. There would have been no fight at the Traders’ Beach, and Amgigh would still be alive.

Then her spirit whispered, “But perhaps one of your sons would be dead.”

“So you believed Qakan,” the Raven said. “But if you left me in order to save our sons, why did you give Takha to the wind?”

“His spirit is with his own people,” Kiin said, “with the First Men. He does not belong to the Walrus People. I have saved one son, and if the Grandmother and the Aunt were right, if their visions and dreams were true, my people do not have to fear a curse, nor do yours.”

The Raven only grunted, then pointed with his chin toward a paddle that lay in the bottom of the ik. Kiin picked up the paddle, turned around, and plunged the blade into the water.

“Be thankful I did not leave you with the First Men hunter Samiq,” the Raven said. “The wound he carries—I have seen such wounds before. The hand is useless. He will never throw a spear again. He will not be able to hunt. His wives and children will starve.”

The Raven’s words made Kiin’s throat ache in sorrow, but she did not answer him. Instead she paddled until she felt Shuku stop nursing. She laid her paddle in the bottom of the ik and looked inside her suk. Shuku was asleep. She watched his gentle breathing, then moved her amulet so it would lie close to his head. She had placed the few bits of gravel and sand she had taken from the Traders’ Beach inside the amulet. A promise to return to Samiq. Even if he could not hunt.

“We will not stay with the Walrus People forever,” she said to her son, but she spoke quietly so the wind that cut in across the bow of the ik would not take her words to the Raven’s ears.

But her spirit said, “Can you risk a return? Can you chance that the Raven will follow you, will see Takha, recognize him as your son? What if he fights Samiq again? If Samiq cannot hunt, how can he fight?”

“In several years, the Raven will not be able to tell Takha from any other small boy,” Kiin answered. “Men do not see babies in the same way women do.”

But her spirit said, “Do not let your anger make you believe the Raven is stupid. There is not so much difference between women and men as you might think.”

Kiin picked up her paddle, and as she thrust its blade against the waves, the Raven said, “I would not have killed our sons, Kiin.”

And when he said the words, Kiin knew he spoke the truth. She set her paddle across the top of the ik and looked back over her shoulder at him. “There are so many ways a child can die,” she replied.

“I am strong enough,” the Raven said. “Takha would have been safe.”

“Better that his death be a gift to the spirits than something done in hate,” Kiin said. Stroking the front of her suk, the bulge that was Shuku, she said, “We have this son.”

The Raven nodded, but said, “You cannot call him Amgigh. His name is Shuku.”

Kiin raised her head and, calling back to the. Raven, she said, “The part of my son that is Walrus People will be Shuku. His spirit name is Amgigh.”

Kiin waited for the Raven’s answer, but he said nothing. She picked up her paddle and looked toward the sun. Its path across the sky grew lower each day.

“Too soon the sun turns toward winter,” her spirit said.

“We have lived through other winters,” Kiin answered, and paddled in silence.

Chagvan Bay, Alaska

THE WALRUS PEOPLE’S VILLAGE had not changed, and though Kiin had been gone nearly four moons, it suddenly seemed as though she had left only the day before. The gray beach shale, the thick smell of oil-lamp smoke coming from the lodges, the dark red strips of walrus meat drying on racks at the edge of the village, women in groups repairing willow-withe fish traps—all were the same.

Men gathered to help the traders pull iks and ikyan ashore. Young boys reached into the boats, prying at bundles of trade goods. Kiin felt a small edge of her sorrow lift as she watched Ice Hunter’s ineffective attempts to stop so many quick brown hands. She did not want to see the questions in the eyes of the Walrus People women, so she pushed her way through the crowd and up the rise of the beach toward the long earth-and-walrus-hide lodges.

She crawled through the entrance tunnel of the Raven’s lodge. Most Walrus lodges had sod walls, stacked and braced with logs. Each roof was a peaked double layer of walrus skins over willow poles, the walrus skins yellow in the glow of day.

But the Raven’s lodge, though long and narrow like other Walrus lodges, had a sod-and-driftwood roof, like the roofs of First Men ulas. Raven’s lodge was warmer than the other Walrus lodges, but always dark, without even a roof hole, such as First Men ulas had, to let in light.

As she came out of the entrance tunnel, Kiin braced herself for the giggling questions of Grass Ears’ two wives, but their portion of the lodge was empty.

“Perhaps Lemming Tail, too, is not here,” said Kiin’s spirit voice. Kiin carried that hope with her as she stepped through the walrus hide dividing curtains into the Raven’s side of the lodge.

“So you have come back,” Lemming Tail said without even the politeness of a greeting. She made a face and turned away from Kiin to paw through the storage cache.

Kiin set down her walking stick and carried the pack she had brought from the ik to her sleeping platform. Shuku’s cradle was strapped to the top of the pack. Kiin untied the cradle and stepped up onto her platform bed to hang the cradle from the lodgepoles.

Lemming Tail turned to point at the Raven’s sleeping platform. “Hang it there,” she said. “I do not share his bed.” She patted her belly, and chortled. “You cannot tell yet, but I carry his son.”

“A son?” Kiin said.

Lemming Tail shrugged. “Or daughter,” she answered.

For a moment Kiin paused, looked into Lemming Tail’s round and beautiful face, then she said, “You and I will share this bed. I will not move to his until he tells me to.”

She hung the cradle, then lifted her suk to pull Shuku from his carrying strap. She laid him on the sleeping platform and loosened the soiled sealskin wrapped between his legs. During the days of travel from the Traders’ Beach, she had not been able to clean him well, and his buttocks were red with rash.

Kiin went to the food cache and, reaching in over Lemming Tail’s arms, pulled out a seal stomach container of oil.

“You do not ask, you take?” Lemming Tail said, sitting back on her heels to stare at Kiin. When Kiin did not answer, Lemming Tail stood, glanced over at Shuku, and asked, “Where is Takha?”

“At the Dancing Lights with his grandfathers,” Kiin said. “Given to the wind.” She pulled out the ivory plug that blocked the end of the seal stomach, dipped her middle finger into the oil, then smoothed it over Shuku’s legs and buttocks.

Lemming Tail walked over to stand beside Kiin. She watched for a moment, then reached for the oil. “It is mine,” she said and grabbed the container, lifting it so that the soft sides of the seal stomach squeezed in against the oil. Oil squirted out the top opening and onto the bedding furs.

Kiin dipped her hands into the spilled oil and continued to clean Shuku. Lemming Tail carried the container over to the storage cache and squatted there with it between her legs.

Kiin wrapped Shuku in clean strips of sealskin, then she spoke to him, waiting for his eyes to catch her eyes, but he turned away from her to stare at his hands. “He misses his brother,” Kiin’s spirit whispered, and Kiin, pain again rising in her chest, closed her eyes and pushed away her spirit’s words.

Kiin lifted Shuku into his cradle and tried not to remember when Takha’s cradle hung beside Shuku’s, when Takha’s body was a warm bundle stretching the soft sealskin sling of his cradle as Shuku’s did now. Kiin gave the cradle a push so it swung gently from the lodge-poles. She walked back to her pack and picked up her walking stick. She ran her hands down the water-worn smoothness of the wood, then held the stick so Lemming Tail could see its pointed end.

“This is more than a walking stick, Lemming Tail,” she said.

Lemming Tail dipped one finger into the oil container and looked up at Kiin. She smirked and said, “You are telling me it is something sacred, an amulet or a spirit caller?” She licked the oil from her finger.

“No,” said Kiin, “it is a spear. For months before the Raven found me, I lived alone. But I did not go hungry. I was all things on that beach where I lived. I was hunter and I was trader. I was mother and I was grandmother. I was carver and I was shaman. I was chief of my own village.” Kiin braced her legs, standing with feet far apart. She lifted the spear and pointed it at the top of Lemming Tail’s nose, in the narrow place between Lemming Tail’s eyes.

“Do not ever take anything away from me again,” Kiin said.

Lemming Tail’s mouth opened, but she said nothing. Slowly, she pushed the ivory plug back into the seal stomach container. She kept her eyes on Kiin and wiped her fingers over the black tattoo lines on her lower legs. “The oil is yours, my sister,” said Lemming Tail in a small voice.

“Good,” Kiin said, then added, “I give half to you. Perhaps you should use it to fill our lamp. It smokes.”

Kiin spent the rest of that day repairing her suk and unpacking bundles that Ice Hunter had left in the Raven’s lodge. At first Lemming Tail hovered over Kiin as she untied each bundle, but finally the woman sighed and said, “He cares for no one but himself. He promised me necklaces and furs, but see, there is only food, oil, and carvings.”

Kiin did not answer, but worked until everything was put away, then, seeing that Shuku still slept, she picked up a small bladder of oil she had saved from one of the trade packs and said to Lemming Tail, “I go to see the Grandmother and the Aunt. I will be back soon. Watch Shuku.”

Kiin took the long way, walking behind lodges and up around the village refuse pile, so she would not have to talk to other women. Let their questions wait for another day when Kiin’s tears were not so close to her eyes.

She used a branch to scratch at the woven grass door flap of the old women’s lodge.

“You did as we told you,” called out Woman of the Sky, her voice high and thin.

A chill raised bumps on Kiin’s arms and scalp. How did Woman of the Sky know it was her? Kiin crawled into the lodge and stood. She straightened her suk then walked between stacks of death mats to squat before the old women.

Woman of the Sky’s hands stopped their work on the death mat she and her sister were weaving, but Woman of the Sun still wove, and as she wove, she swayed, eyes closed, so that Kiin was not sure she was listening.

“Yes,” Kiin answered. “I gave my son Takha to the wind spirits.”

Woman of the Sky leaned forward, pressed her fingers to Kiin’s lips. “Do not say his name,” she said. “It may bring him here, back to us.”

Kiin stood up. Perhaps she had been foolish to visit the old women so soon after returning to the village. Already she could feel her spirit’s frantic need to leave their lodge. What good would it do to stay here and listen to the old women and their talk of curses?

“Your brother is dead?” Woman of the Sky asked.

“Yes, the Raven killed Qakan and I buried him.”

“Tugidaq,” the old woman said, using Kiin’s spirit name, “why do you say his name? Why take chances with the spirits? He has cursed you enough. What brother should use a sister like a wife? What brother forces a sister to do what only a wife should do?

“But now that your son is with the wind spirits, we are safe; this village is safe. You are a strong woman, Tugidaq.”

Kiin looked long into Woman of the Sky’s face. “Yes, Grandmother, I am strong,” she said. She handed the woman the oil bladder. “My husband brings you oil from the Traders’ Beach,” Kiin said.

Woman of the Sky took the bladder and smiled. “Ice Hunter brought us oil, too,” she said and set the bladder down beside her. She began weaving again, and Kiin looked over at Woman of the Sun. Woman of the Sun’s eyes opened. She smiled at Kiin but said nothing. Kiin sat down beside the old women and for a time watched as their hands, small like children’s hands, wove split grass into the death mat. They did not speak, nor did Kiin, and finally the silence seemed to fasten itself to the ache in Kiin’s chest, enlarging the pain of her loss.

“I am leaving now,” Kiin finally said and stood. Woman of the Sky continued to weave, but Woman of the Sun followed Kiin through the entrance tunnel. As they stood outside, the wind from the bay blowing cold, the old woman reached out, clasped Kiin’s arm, looked deep into Kiin’s eyes.

“Sometimes my dreams are a curse,” Woman of the Sun said. “Sometimes I wish I did not know those secrets the spirits choose to tell me.” She sighed, looked out toward the bay. Finally she said, “What you have done, you have done. My sister does not know and I will not tell her, even if Raven blames us for Takha’s death. I know what it is to have a son. I hold no anger toward you.”

Kiin’s hands clasped over her suk, but her suk was empty, no baby suckling her breasts.

“He is not the one,” Woman of the Sun said, and gestured toward Kiin’s suk as though Shuku were tucked inside. “He holds no curse. It is the other, Takha, but perhaps he is far enough away for us to be safe.”

For a moment, Kiin saw Takha, cradled in Three Fish’s arms, and Kiin’s need for him was like a point of ice piercing through skin and muscle to lodge itself at the center of her heart.

“You are wrong, Aunt,” Kiin said. “I gave him to the wind spirits. He is dead.” And Kiin turned away, walked back to the Raven’s lodge.

LEMMING TAIL SQUATTED AND DUG her fingers into the bowl of meat. She looked up at Raven and spoke through the food in her mouth. “It is good, husband. Did you bring me gifts?”

Raven frowned. “The meat is not gift enough?” he asked, but as Lemming Tail pinched her mouth into a frown, Raven squatted beside one of his trade packs and loosened the strings. He pulled out a necklace, something strung with beads of birdbone and shells. He tossed the necklace to Lemming Tail, then reached again into his pack for a second necklace.

“For you,” he said to Kiin and carried it to her, dropping it over her head. It glistened against the bare skin of her chest, drooping into a long loop between her breasts.

Kiin lifted the necklace and studied the beads. Each was a circle cut from whale jawbone. Each circle was drilled with a hole and etched with fine lines. It was beautiful, almost as beautiful as the shell bead necklace Samiq had made her, but the Raven’s necklace felt cold and heavy against her skin.

“Thank you,” she said.

“I see you no longer have your other necklaces,” he said.

“I gave them as gifts.”

The Raven’s eyes hardened. “You should have kept the carving,” he said.

No, Kiin thought, though she did not answer him. I am glad I gave it to Three Fish. It will give her power to be a good mother to Takha.

“That carving could bring us enough meat for the whole winter,” the Raven said.

Kiin lowered her head, and the Raven turned away. She went to the sealskin boiling bag that hung above the oil lamp and dipped out a bowlful of meat. She handed the bowl to the Raven, then filled one for herself and went back to squat beside her sleeping platform. Lemming Tail slid over to sit beside Kiin. She studied her own necklace, then looked over at Kiin’s, and her bottom lip thrust out into a pout.

Kiin did not look at the woman, but suddenly the Raven was standing beside them, a sealskin sewing case in his hands. He gave the case to Lemming Tail and said to her, “Another gift. Keep it or trade it. Perhaps Shale Thrower has a necklace she will give you for it.”

Lemming Tail smiled and, looking at Kiin from the sides of her eyes, slid her tongue over her teeth.

“We brought back other trade goods,” the Raven said to Lemming Tail. “If you go now, you will be first to see what other wives have. You will get the best trades.”

Lemming Tail scooped the rest of her food into her mouth and scurried into the basket corner. She set the sewing case in the bottom of a large basket, then covered it with several fox pelts and a grass mat. She pulled on her parka and, with another smile at Kiin, left the lodge.

The Raven finished eating, then held his bowl out toward Kiin. He looked at her through slitted eyes, and Kiin’s heart hammered in her chest. She knew he wanted something more than food, but she took his bowl, started toward the boiling bag.

The Raven caught the back panel of Kiin’s woven grass apron. “Not yet,” he said and pulled her toward him.

Kiin set the bowls on the floor and waited as the Raven stood and stretched his arms over his head. He pulled off his parka and caribou skin leggings, then moved to stand in front of Kiin. He untied the band that held his apron, letting it fall to the floor.

Kiin looked back over her shoulder toward Shuku’s cradle. But her spirit whispered: “Do not look to your son to help you. You must be his strength. When you left the Traders’ Beach, you knew you would have to be wife to the Raven. If you resist him now, what chance will Shuku have? The Raven might decide to treat him as slave instead of son.”