EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

PATRICIA BOSWORTH

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Find a full list of our authors and

titles at www.openroadmedia.com

FOLLOW US

@OpenRoadMedia

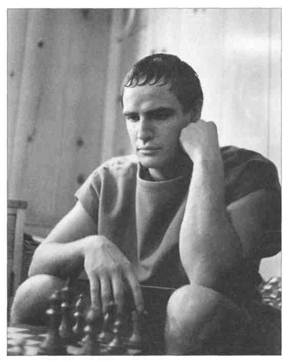

In 1952 photographer Ruth Orkin captured Brando engrossed in a chess game on the set of the film Julius Caesar. There is such simplicity and balance in this image, because it totally contains his silence. © Ruth Orkin, 1981

FOR MY HUSBAND, TOM PALUMBO

Acting is half shame, half glory. Shame at exhibiting yourself—glory when you can forget yourself.

—Sir John Gielgud

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

EPILOGUE

SOURCES

MARLON BRANDO, NICKNAMED BUD, was born on April 3, 1924, in Omaha, Nebraska. At the time much of the state was recovering from a grasshopper plague that had turned the sky green. Enormous humming clouds ate all the crops and left the fields and gardens brown and bare.

Brando was the only son of Dorothy (“Dodie”) Pennebaker, a radiant, unconventional blonde of Irish heritage, and Marlon Brando, Sr., a salesman for Western Limestone products, who’d inherited a violent temper and martinet ways from his father, Eugene Brandeaux, of French Alsatian extraction. Senior changed his name to Brando shortly before he married Dodie on June 22, 1918. They had had a passionate courtship, starting in high school, and had written many love letters to each other when Senior was serving in the Army during World War I. Brando saved some of the letters but maintained that they did not move him.

Brando lived with his parents and his two older sisters, Jocelyn and Frances, in a comfortable wood-frame house at 3135 Mason. They were frequently visited by “Nana,” their twice-married, independent-minded grandmother, who was known for her outspoken views on immigration and women’s rights and as a master speed reader. Nana was also a devout Christian Scientist and a lay healer; in later years she would say she could speak with the dead. Often Nana spent hours with her daughter Dodie and her grandchildren, discussing history, religion, art, politics. “She inspired us,” Jocelyn remembers, and Brando and his sisters needed inspiration.

Their father, Marlon Senior, was a moody, unpredictable man given to fierce rages, and they were terrified of him, although he was rarely with his family. He spent most of his time traveling all over Missouri and Iowa as a salesman. He was often seen in Chicago brothels and speakeasies; he had frequent affairs. When he returned home, he and Dodie would drink heavily and fight. It was Prohibition, so they brewed their beer in the kitchen.

In 1926, when Brando was two, he and his family moved with Nana to a bigger house at 1026 Third Street, and Dodie began filling the living room with bohemians and oddballs, as well as friends from the community theater, such as the Fonda family and the parents of Dorothy McGuire, the actress.

The atmosphere was relaxed and casual. Dodie often received people in bed, her quilt littered with magazines and crossword puzzles. Brando has told friends that his earliest memory was lying in bed with his mother, sharing a bowl of milk and crackers.

Although Dodie truly loved her children, she was seldom home. Housework bored her, and she was hopelessly stagestruck. Just before Brando was born, she’d joined the fledgling Omaha Community Playhouse, and she escaped there whenever she could, even attending rehearsals of shows she had no part in. She sat in on auditions and gave the young Henry Fonda his first job. Over the next four years she played many roles, from Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie to Julie in Ferenc Molnár’s Liliom. The local critic said of that performance: “Mrs. Brando is profoundly moving (especially in the death scene). Her reserve has the effect of numbing in sorrow,” and another wrote, “Amazingly realistic.”

With his mother away from the house so much, Brando began relying on the loving attention of his nurse, Ermeline, who was “Danish, but a touch of Indonesian blood gave her skin a slightly dark, smoky patina,” as he writes in his autobiography. At night they would sleep together in the nude, and Brando, then age five, would wake up and look down at her body and fondle her breasts, and then he would crawl all over her. “She was all mine; she belonged to me and to me alone.”

When he was seven, Ermi left him to get married, and Brando felt abandoned. He began to stutter. He was a fat-bellied little boy, serious and determined, with a penetrating stare and boundless energy. Jocelyn had to take him to kindergarten on a leash; otherwise he would have run away.

In 1930 Senior got a better job in Illinois as the general manager for the Calcium Carbonate Company, so the family moved to Evanston. Dodie agreed to the move, but she resented it; she had to leave the playhouse at the height of her success. Her drinking increased. She would say, “I’m the greatest actress not on the American stage.” Senior was always away. Sometimes she would wander around their new house on Sheridan Square, crying. Then she would sit down at the piano and begin singing. Her children would sing with her.

“My mother knew every song that was ever written,” Brando writes in his autobiography. He memorized as many of them as he could. Today he can still remember the lyrics of all those songs: Greek songs, Japanese songs, Irish songs, German songs, American songs—all the songs his mother ever taught him.

By the time he was eight, Bud Brando was the “star” of the neighborhood, mimicking people, climbing in and out of windows (something he would do for much of his life), swinging at the end of a rope while letting loose with a Johnny Weissmuller yell so piercing it could be heard for blocks. He was “a free spirit,” a friend remembers, “a real individualist. Even as a little kid you knew he was going to do anything he set out to do. And he was a prankster. Like he’d pull the fire alarm and then race off and hide when the fire engines zoomed down the street.”

At Lincoln School he was very popular. He and another sixth grader, Wally Cox—frail, bespectacled, and skinny—became inseparable. “Marlon thought Wally was a genius. Maybe he was,” said Pat Cox, Wally’s third wife. “He certainly was tremendously knowledgeable, an omnivorous reader. Even at the age of ten he knew about botany, the names of different butterflies and birds, and every wild-flower in the world. He and Marlon would hike all over the place, talking a mile a minute.” They loved to have contests: Who can eat faster? Who can hold his breath longer?

Wally’s mother was a mystery writer. She also was an alcoholic, so Wally and his sister were often left to be cared for by near strangers whenever Mrs. Cox went off on a binge. Later she abandoned them for a lesbian lover. Soon Wally was dropping by the Brando house; he would stay for supper and then the night. “Wally became like a member of the family,” Jocelyn says, and when he was tormented by classmates, Brando would protect him as he protected sick animals and bums. He once brought a bag lady home from off the street. She was in rags and seemed quite ill. Brando had a tantrum until Senior agreed to take the bag lady to a nearby hotel where she could recuperate in a clean bed.

Brando at the age of eight with his beloved mother, Dodie, probably the most important person in his life. Photofest

By 1936 Senior’s philandering had become so extreme that Dodie was beside herself. One night when he came home with lipstick smeared on his underpants, she started screaming and crying, and he took her into their bedroom and began beating her. Brando, age twelve, rushed into the bedroom and threatened to kill his father if he didn’t stop. It was a scene that Brando later described to his friends over and over, and he would refer to his father’s unpredictable nature: affectionate and sensitive one minute and livid with anger the next.

He was repelled by what he felt was his father’s hypocrisy. Although Senior was raising his kids by the “Good Book,” he was a relentless womanizer, and by forcing the family to move from Omaha, he’d ruined Dodie’s life by depriving her of her career on the stage; he had no compassion for her huge despair.

Throughout his adolescence rage propelled Brando: rage against his father and fantasies of revenge. Decades later, in the 1980s, with the help of his therapist he would realize how his family had been an incubator of psychological violence, and that society had no way of controlling it or of stopping it because it was a private family matter, conducted behind closed doors.

For a while Dodie and the children went to California to live with her half sister, Betty Lindemeyer, and Nana. Brando and his sisters attended Lathrop Junior High School. A couple of times Henry Fonda visited and drove Dodie to Hollywood; he had never forgotten how she had given him his start. But she was drinking a lot and sometimes disappeared for days at a time.

Two years later, in 1938, the Brandos reconciled, and Senior bought an old farmhouse in Libertyville, Illinois, thirty-five miles outside Chicago. There was a barn and stables and acres of land. Brando loved the animals “because an animal’s love is unconditional.” He especially loved his dog, Dutchy, a Great Dane, and a cow named Violet. “I’d ride Violet out into the field and I’d put my arms around her and kiss her. Cows have very sweet breath because of the hay they eat.”

But life was no better for Brando on the farm. Dodie hated housework and hated being so isolated in the country, and the place was often a mess. Brando was doing poorly in school. He’d stay in his room, listening to Gene Krupa records. He loved playing the drums, and he carried his drumsticks everywhere, beating out a frantic tat-tat on coffee tables and desktops. He drummed so much he’d forget to milk the cows or do his homework, and then his father would get after him, and they’d start yelling at each other on the porch. Dodie would say, “Can’t you have a civilized discussion? Why can’t you speak normally?” and she’d shoo them out into the backyard, where they’d continue to shout. Often Brando would simply run off.

He was starting to date. One of his first girlfriends, Carmelita Pope, remembers inviting him over for pasta; after they’d eaten, he would go out on the sunporch with her father, who was a lawyer, and ask him all sorts of questions. Brando was insatiably curious about everything. He was quite fat then, and Senior insisted he work out with barbells and bench presses until he transformed himself into the body beautiful.

He kept on playing the drums and founded a band called Keg Brando and His Kegliners. But his grades got worse. At school he excelled only in sports and in dramatics, especially pantomime. He failed all his other subjects and was held back a year. He was close to sixteen and still a sophomore. It was humiliating; he became a truant.

When his father found out, there were more violent shouting matches. Brando did not remind him that often instead of attending classes he went to Chicago to hunt for his mother, whom he usually found slumped in some bar passed out in her own vomit. One time he dragged her naked into a cab and brought her home; again Senior started to beat her, and again Brando managed to stop him.

In May 1941 Brando was expelled from Libertyville High for chronic misbehavior. His last prank had been pouring hydrosulfate into the blower at school so a rotten-egg smell pervaded the classrooms. He possessed a love of mischief other students found admirable.

Senior was hopping mad. After much deliberation he packed his son off to his alma mater, Shattuck Military Academy in Fairbault, Minnesota, where he had been an honor student. The same would not hold true for Brando; he had poor study habits, and his concentration span was short. He simply could not conform. He was sixteen then, startlingly handsome, with a Roman nose and a sensual mouth, and his taut, muscled body practically undulated when he moved, like a graceful tomcat on the prowl.

He was funny; he had no pretenses. He refused to kowtow to the school bullies, and he acted tough, often insolent. He would fight anyone who came on to him; he had a hair-trigger temper. He loved challenging authority and could not be controlled. Once he wrote “shit” on the blackboard and then lit a fuse doused in Vitalis, which contained alcohol, and poof! the word became indelible on the board. Another time he stole all the silver from the dining room so the cadets couldn’t eat their breakfast; classes were delayed until the silver was found. The student body thought his pranks were audacious; he became very popular. (Brando says his favorite prank was his disabling of the school’s bell. The noise so maddened him that one night he shimmied up to the bell tower and cut the clapper off, then buried it.)

He writes, “I had a great deal of satisfaction challenging authority successfully. I had no sense of emotional security. I didn’t know later why I felt valueless or that I responded to worthlessness with hostility.”

He has said he was encouraged by only one teacher, Duke Wagner, who taught him Shakespeare and the glory of language and who perceived his great natural gift for mimicry. Once Brando transformed himself into the gangster John Dillinger and had all the students squirming in their seats. On Thanksgiving in 1941 he performed in three one-act plays at Shattuck. The school newspaper wrote, “The new boy shows enormous talent.”

However, his grades continued to be poor. Every week he wrote to his parents, asking them to believe in him and telling them over and over how much he loved them, hoping his words would persuade them to say they loved him. But Senior and Dodie never wrote him back or visited him in the two years he was at Shattuck.

The summer of 1942 Brando did not go home to Libertyville right away. Instead he rode the rails and lived in hobo camps, sitting by campfires with the drifters, eating mulligan stew, listening to their stories, how some were hiding out from police or irate wives. He learned their lingo and their sign language; a certain sign marked in chalk on a fence meant the neighbor down the road was hospitable.

Back on the farm, he and his mother had a disjointed conversation about his going into the theater later on when he’d finished high school. But he was thinking he might become a minister, he writes in his autobiography, “Not because I was a religious person, other than having an inexhaustible awe and reverence for nature, but because I thought it might give me more of a purpose in life.” Actually he had no idea what he wanted to do.

Returning to Shattuck, he dyed his hair red. He made twelve visits to the infirmary (he faked a fever by holding the thermometer to a hot-water bottle). He was the school’s reigning clown and rebel, loved and admired by everybody. That fall he won the lead role in Four on a Heath and was able to show off his remarkable ability to take on an accent (in this case, English). In the final scene of the play he hanged himself and did it so realistically that, after the curtain came down, the audience burst into frenzied applause and his performance was the talk of the school.

But he continued to flunk all his courses. He’d hide out in the study hall, reading National Geographic. One afternoon he came across some color photographs of the island of Tahiti, with its pure white sands and thick, rustling palms. And the expression on the Polynesian natives’ faces—it was an expression he’d never seen: “happy, unmanaged faces,” he wrote, open maps of contentment. He vowed he would go to Tahiti someday.

In May 1943 Brando was put on probation at Shattuck for talking back to an officer during maneuvers. It was considered insubordination, so he was confined to campus. But after a couple of hours he got bored and took off for downtown Fairbault. Of course, his absence was discovered. When he returned to the school, hours later, he was sent to his room, and the faculty met to decide his fate. He was promptly expelled.

Brando recalls that it was a shock. He wandered from room to room in a daze, saying good-bye to all his friends. When he reached Duke Wagner’s office, the teacher reassured him that everything would be all right and that the world would hear from him someday. Brando has said that he will never forget those words; no one had ever expressed confidence in him before. Then Wagner hugged him tightly, and Brando found himself sobbing uncontrollably in the teacher’s arms.

He took the train home almost immediately. His parents seemed bitterly disappointed in him.

Meanwhile, at Shattuck, the entire student body was up in arms about his expulsion, feeling it was both extreme and unfair. Eventually the students went on strike and stayed on strike until the faculty agreed that he be reinstated. The principal then wrote to Brando, inviting him to complete his studies and be graduated the following year. But he hated the military academy so much he refused to go back. He never graduated from high school, but for years he kept the cadets’ letter of support framed in the bedroom of his home in Beverly Hills. He has always felt embarrassed by his lack of education.

For the next six weeks after leaving Shattuck, Brando dug ditches for the Tile Drainage Company. His father had arranged the job for him, and he loathed every minute of it, although he did enjoy earning money on his own. But home life on the farm was lonely. His sister Frances was in New York, trying to be a painter, and Jocelyn was there too; she’d already appeared in one Broadway play. By fall Brando had decided to join them. He’d visited Frannie in New York briefly the previous Christmas and had written her afterward that he wanted to live there.

He might even try acting, he thought. His father’s response was to scoff, “The theater? That’s for faggots! It’s not man’s work.” Then he added that Brando could never be a success anyway: “Take a look in the mirror and tell me if anyone would want to see a yokel like you on the stage!” Hearing the contempt in Senior’s voice, knowing he had no faith in him, made Brando want all the more to excel at something to prove himself. But at what?

HE ARRIVED IN NEW York during the late spring of 1943, dressed in faded dungarees and sporting a red fedora. “I thought I was going to knock everybody dead,” he says. The first thing he did was to have his shoes shined in the midst of the bustle of Penn Station. He felt sorry for the little shoeshine boy and tipped him five dollars. Then he grabbed his duffel bag and plunged into the crowds surging on West Thirty-fourth Street.

After living on a farm and in small towns all his life, he was astonished by the noise, heat, dust, and confusion of wartime New York. He couldn’t get over the honking, grid-locked traffic, the welter of neon signs at Times Square. And so many people! Refugees from Hitler’s Germany, artists, musicians, poets, everybody cramming into New York, hoping to find fame and fortune.

He kept bumping into servicemen on leave, all out for a good time. Brando had smashed a knee during football practice at Shattuck, and he had poor eyesight, so he was 4-F, a fact that didn’t bother him. He had no interest in going off to battle, but his father was disappointed.

For a while Brando roomed with his sister Frannie, who lived in a tiny apartment on Patchin Place. He was hardly ever there; he stayed up all night, went to parties, observed everybody very seriously. “He was naïve,” his sister Jocelyn recalled. “It took him awhile to become disillusioned with people. He was so trusting.”

Brando’s first serious girlfriend was Celia Webb, an intense, elegant little lady from South America. She was ten years older than he, with a young son. She lived across the hall from Frannie in a one-room apartment. Her husband was away in the Army.

Celia was a window dresser “and a great cook,” someone said. Brando moved in with her, and they were together off and on for a long time. Their friendship lasted for many years. “She was very important to me, but after [Celia] there were many other women,” he says.

“Marlon controlled his women,” says the dancer Sondra Lee, who was another one of Brando’s early girlfriends. “It was never a situation of equals.” She recalls dropping by to visit him in a fleabag hotel, one of many he inhabited before he became a movie star. “Marlon opened the door, and behind him there was Celia in bed. Marlon was very charming to me, but I got the message I couldn’t stay. We all knew she was special.” Sondra became friends with Celia. “In those days all of Marlon’s girls were friends. We accepted the situation with him. He was like a god, a king. We accepted the fact he was different. It was rather unsettling. He seemed to have appeared out of nowhere, as if he were from another world. He would never allow himself to be tied down.”

As soon as Brando’s money ran out, he got a job as an elevator operator at Best’s department store. He was also a short-order cook and a night watchman in a factory. After work he’d regale his sisters with silent portraits of the people he’d been observing on the subway: the gum-chewing secretary adjusting her stockings; the one-legged derelict begging for pennies outside Carnegie Hall. Brando could transform himself into anybody instantly, and the transformation was completely organic. “If he played an electrician, you could see the wires,” someone said.

Friends encouraged him to become an actor. Why not? He had great natural gifts and was trained for no other profession. But he still wasn’t sure that was what he really wanted to do. Maybe he’d become a writer or a director. The one thing he really wanted was to be educated. The next time his father phoned from Libertyville, Brando said, “Pop, I’m going to study at the New School.” Senior agreed to send him tuition money but added that he hadn’t much hope, he wasn’t going to amount to anything. That made Brando want to try harder, to prove his father wrong.

In the fall of 1943 Brando enrolled in the Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research, on Twelfth Street in Greenwich Village. The workshop had been established in 1940 and was a magnet for aspiring actors from all over the country. In Brando’s class were Harry Belafonte, Elaine Stritch, Gene Saks, Shelley Winters, Rod Steiger, and Kim Stanley, to name only a few.

Brando took fencing, dance, and yoga and studied with the dictatorial German émigré Erwin Piscator, a small, highly keyed man who’d revolutionized European theater by using bare stages and harsh, realistic lighting. Brando resisted Piscator’s authoritarian ways, much preferring the classes he took with the master acting teacher Stella Adler, the flamboyant, imperious former member of the Yiddish theater and the daughter of the great Yiddish actor Jacob Adler.

Mercurial, with thick blond hair, huge, expressive blue eyes, and a curly mouth, Adler exuded a glamour and a kind of radiant intelligence Brando had never seen before. Her teaching was volatile and scholarly; her lectures, especially on Chekhov and Ibsen, were delivered with a passionate evangelism. She kept her students spellbound, alternately raging and purring as she spoke. She dared them to use their imaginations, to be larger than themselves, and, above all, never to be boring.

Adler’s most creative years had been spent in the 1930s with the Group Theatre, the experimental Depression-era company founded by Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford. It was a pivotal moment in the growth of American theater, uniting playwrights such as Clifford Odets and William Saroyan, directors like Elia Kazan, and actors such as John Garfield and Franchot Tone, who worked to shape theater that was often politically relevant. Members of the ensemble were leading interpreters of the Method, and the Method revolutionized American theater. In the past, classical acting instruction had focused on developing external talents, while Method acting was the first systematized training that developed internal abilities-sensory, psychological, and emotional.

Strasberg, who later headed the Actors Studio, rooted his view of the Method in what Konstantin Stanislavsky had stressed early in his career: that the actor should perform affective memory exercises, improvise, and conjure up the conscious past to convey emotion—for example, dwell on personal tragedy to show anguish.

Adler opposed this approach. In 1934 she went to Paris with Harold Clurman, and she studied with Stanislavsky for five weeks. She found he’d revised his theories. He now stressed that the actor should create by imagination rather than memory, and that the key to success was “the truth. Truth in the circumstances of the play.”

Adler’s precepts for acting revolved around concentration, attention to detail, and the creation of specific physical action for the character. “Your truth is in your imagination,” she said. “The rest is lice.” She believed that the art, architecture, and clothes of an era were crucial to shaping a role, and she always explored texts for performance clues. However, in class, she didn’t work with plays that much; instead she used improvisations and exercises to release the actors’ inhibitions. “Don’t act. Behave,” was one of her mottoes.

All her New School students were neatly dressed, so when Brando appeared in her class wearing threadbare dungarees and filthy sneakers, she did an exaggerated double take. “Who’s the vagabond?” she demanded.

“Marlon Brando,” he answered, staring at her until she blushed. His handsome, sullen face was stubbly with beard.

Within weeks she was calling him “extraordinary.” It was probably because of what he achieved so effortlessly in the first animal exercise she gave him. She’d instructed the entire class to behave like chickens in a henhouse after they were told that a bomb was about to explode over them. While the other students hopped frantically around the room, clucking and flapping their arms like wings, Brando sat quietly in a corner miming the laying of an egg. “That’s exactly what a chicken would do under the circumstances, my darling!” Adler exclaimed.

He was nineteen when they met. She was forty-one and “very beautiful,” Brando recalls. Soon she was inviting him to her overdone apartment on West Fifty-fourth Street and introducing him to her four sisters; her daughter, Ellen; her eighty-year-old mother, Sarah; and her second husband, the esteemed critic and former Group Theatre director Harold Clurman. Sometimes Brando accompanied them to a Childs restaurant on Columbus Circle, where they had coffee and bagels with the playwright Clifford Odets.

Other times he sat in her living room, mimicking her every move. She’d sip scotch, he’d sip scotch; she’d light a cigarette, he’d light a cigarette; she’d cross her legs and finally notice what he was doing and say, “Oh, Marlon, stop it!” She found his ability to take on the physical characteristics of other people truly remarkable. Later she said, “he takes in everything, including the size of your teeth.” Brando eventually took in her vanity and willfulness and used it in a variety of characters over the years. He had no fear of his androgyny. He loved playing around with gender.

Adler had appeared in more than a hundred plays; she’d been acting since childhood. She was a bravura actress who’d never been given the chance to be a huge star in Hollywood, as she longed to be. She wanted to be recognized and famous. She was bitterly disappointed that she wasn’t.

“Stella taught me everything,” he would say. She would say, “I taught Marlon nothing. I only opened the doors to feeling and experience, and he walked right through them, and after that he didn’t need me.” Philip Rhodes, Brando’s close friend and makeup man for forty years, says, “Stella showed Marlon how to focus his anger towards his father; she helped him channel it creatively.”

By December, Brando was appearing in Dramatic Workshop shows. His first appearance was in G. B. Shaw’s Saint Joan. He followed that with J. M. Synge’s Riders to the Sea, and then he played Prince Anatole in Piscator’s condensed version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. “He was always ready, like Mozart,” said a fellow student. “Everybody else was struggling, but for Marlon there was no sign of struggle or effort.”

Then in January 1944 Brando played the double role of the young Jesus Christ and a doddering old schoolteacher in Gerhart Hauptmann’s Hannele’s Way to Heaven. “Marlon was absolutely breathtaking,” says Elaine Stritch. “You knew you were in the presence of an acting genius.” He followed that tour de force with roles in Shakespeare, Molière, and a children’s play by Stanley Kauffmann titled Bobino, in which he performed “a brilliant little pantomime.”

By then he’d reunited with Wally Cox, his dear childhood friend from Evanston. Cox, still skinny and bespectacled, was working as a silversmith and puppeteer to help support his mother, who was suffering from a partial paralysis.

He and Brando sat for hours, talking about sex and death and love and women. Everett Greenbaum, who later wrote Mr. Peepers for Cox, says, “What bonded them was their intense curiosity about everything in the universe. Wally spoke four languages and knew about insects, botany, and birds. He understood every page in Scientific American.” But both men were “also attracted to the dark side.”

“Marlon especially, he really went for trash, for creeps—both men and women,” says another friend. “Rita Moreno was one of the few decent women he ever went with. Marlon dug the worst aspects of life, and of himself, and then he used them for himself as an actor and turned them around—like years later, in The Godfather, where you see this evil criminal playing so lovingly with his grandson.”

Meanwhile, life on the farm in Libertyville had become unbearable for Dodie. Senior had joined AA and wanted her to do the same, but she could not give up drinking. So she left him and went to New York—to be with her children, she said. After arriving in April 1944, with the family’s ancient Great Dane, Dutchy, in tow, she rented a drafty ten-room apartment on West End Avenue. Senior had agreed to pay for everything, including a part-time maid. Jocelyn moved in, with her new baby son and husband, the actor Don Hanmer, who was on leave from the Army. Frannie and Brando remained in the Village, although Brando dropped by as often as he could, and an assortment of friends usually tagged along with him. The apartment filled up with artists and writers, singers and dancers. The place was never empty.

Dodie would hold court from her bed, and Brando would visit her there. Sometimes he attempted to shock her: He would put on her frilly bathrobe and vamp around in it, especially if he had an audience. He would tease and badger her, and she seemed to enjoy it. Sometimes he tried to provoke her. Once, when they both were in the kitchen, Brando peed in the sink. “Oh, Buddy,” his mother cried to others in the room, “why doesn’t he stop this shit?”

Everyone who saw them together was aware of their deep emotional bond. “Bud worshiped and adored Dodie,” Elaine Stritch said. Dodie in turn idolized him. He was her genius. Somehow she believed that part of that genius was in her too, that he’d inherited it from her.

He was worried about her. The apartment was a mess: dirty dishes in the sink, meals served haphazardly, if at all. She was in the last agonies of alcoholism. She stashed liquor all over the apartment, and he and his sisters could never find it.

Soon Dodie was disappearing for days, and Brando would prowl around every bar on the West Side, hoping to find her. When he couldn’t, he would come back to her apartment and sink into a depression. His feelings of abandonment and resentment and fear would all merge, and then he would have to go to class and perform. Eventually he and his sisters began accompanying Dodie to AA meetings.

That summer Brando joined Piscator’s little theater group out in Sayville, Long Island, where he repeated his triumph in the Hannele play. He had such charisma that the audience gasped when he made his first entrance, in a gold satin suit. One night MCA’s powerful theatrical agent Maynard Morris caught the show, and afterward he went backstage and told Brando he wanted to represent him. Brando appeared indifferent.

He was more interested in girls. He juggled many girls that summer: Celia Webb; a singer, Janice Mars; and a voluptuous young blonde named Blossom Plumb. Near midsummer Piscator caught him holding hands with Blossom in the barn and expelled them from the company immediately, although they both heatedly denied they were doing anything wrong. Later Piscator regretted his action and admitted that Marlon Brando was the most gifted actor he had ever taught, although he wished “he hadn’t been so lazy.”

Remember Mama