Beginning on page 55, is a facsimile reproduction of the original 1935 edition of the work.

To my grandchildren Michael Evans and Lucy Evans

Joel Michaels and Lila Michaels:

Four votes of confidence in our future

INTRODUCTION

My Hours with Virginia Woolf

HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS

Letter from Peggy Belsher of Hogarth Press to Ruth Gruber, Dec. 16, 1931

Letter of Recommendation from Barnes & Noble editor A. W. Littlefield, Feb. 25, 1933

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Virginia Woolf, May 8, 1935

Letter from M. West of Hogarth Press to Ruth Gruber, May 17, 1935

Letter from Ruth Gruber to M. West of Hogarth Press, May 28, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, June 21, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, Oct. 12, 1935

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Virginia Woolf, Dec. 27, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, Jan. 10, 1936

Promotional booklet for lecture bureau representing Dr. Ruth Gruber

Letter from Nigel Nicolson to Ai’da Lovell (for Ruth Gruber), Aug. 31, 1989

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Nigel Nicolson, Sept. 15, 1989

Letter from Nigel Nicolson to Ruth Gruber, Sept. 25, 1989

VIRGINIA WOOLF: A STUDY

by Ruth Gruber, originally published in1935

Chapter One—The Poet versus the Critic

Chapter Two—The Struggle for a Style

Chapter Three—Literary Influences: The Formation of a Style

Chapter Four—The Style Completed and The Thought Implied

Chapter Five—“The Waves”—the Rhythm of Conflicts

Chapter Six—The Will to Create as a Woman

A MYSTERY SOLVED

INDEX

ONE MORNING IN THE summer of 2004, my research assistant, Maressa Gershowitz, came running into the room where I was working.

“Look what I’ve found!” she shouted.

She held up three letters, sent to me by Virginia Woolf.

The letters were as fresh and unwrinkled as if Woolf had written them not in 1935 and 1936, but the day before.

“Where in heaven’s name did you find these letters?”

“You won’t believe this,” Maressa said. “They were in the back of one of your filing cabinets, behind a bunch of old tax returns.”

The past lit up. I shut my eyes, recalling how in 1931-32, as an American exchange student at the University of Cologne in Germany, I had written my doctoral thesis, called “Virginia Woolf: A Study.” Three years later, it was published as a paperback book in Leipzig under the same title. With apprehension, I had sent Woolf the book, and she had invited me to her London home for tea.

I recalled how on that day, the fifteenth day of October, 1935, I had walked up and down the narrow streets of Bloomsbury. I stared up at Virginia Woolf’s Georgian four-story house, which had a balcony overhanging the street.

Everything seemed magical to me. The rain, which had fallen all day, had stopped, and the air was as clean as if it had been scrubbed in a huge washing machine.

I rang the bell at 6 P.M. at 52 Tavistock Square. A housekeeper in a black-and-white uniform opened the door, led me into a dark corridor and up a narrow staircase to the first floor. She tapped on a wooden door, and a man who introduced himself as Leonard Woolf stepped forward.

“Welcome,” he spoke warmly and shook my hand. He was painfully thin, with a long oval face, dark hooded eyes, black hair laced with gray, and an air of sadness and suffering. He took me across a large parlor with sofas on each side, and motioned me to sit in an upholstered armchair close to Virginia.

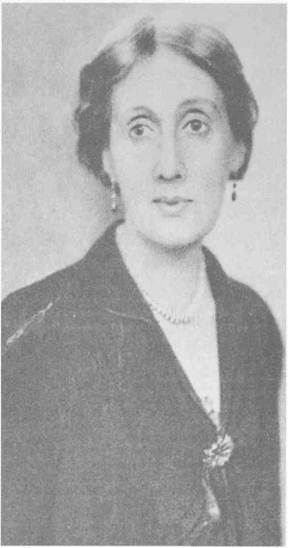

She lay stretched out in front of a fireplace. The fire cast a glow over her carved straight nose, her expressive lips, her melancholy gray-green eyes. The beautiful Nicole Kidman, playing her in the film The Hours, did not need the built-up nose or the dowdy housewife clothes. Virginia Woof was elegant, a woman of grace and beauty.

She was a study in gray: short gray hair cut like a boy’s, a flowing ankle-length gray gown, gray shoes, and gray stockings. In her fingers, she held a long silver cigarette holder, through which she blew smoke into the parlor. There were three of us: Virginia, then fifty-three, reclining on a rug; her husband Leonard behind me, at the far end of the room but leaning forward as if he were hovering over her; and I, sitting inches away from her. I had come to sit at her feet. But now she was lying at mine.

The fire warmed me in front as I faced her, but my back was chilled. I pulled my jacket tight around me and sat in silence, too overawed to speak.

“I looked into the study you wrote about me,” she said. “Quite scholarly.”

Was she praising me? I could scarcely believe it. I did not know whether to thank her or remain silent. I chose silence.

She took a long draft of smoke and said, “I understand from my secretary that you are writing a book on women under fascism, communism, and democracy.”

I murmured, “Yes.”

“And you want to interview me for your book. I don’t know how I can help you. I don’t understand a thing about politics. I never worked a day in my life.”

I wondered how she considered that it was not work to write groundbreaking novels, brilliant essays, and book reviews, and why she would demean her knowledge of politics. Her books were full of politics; her friends in the Bloomsbury crowd were energetic political thinkers—Lytton Strachey, the poet and historian who had wanted to marry her but whom she rejected; John Maynard Keynes, the economist; Roger Fry, the painter whose biography Virginia later wrote; and T. S. Eliot, the poet whose lines like “In the room the women come and go, talking of Michelangelo” often sang in my head.

“I understand,” she said, “that you have been traveling. Where have you been?”

“Germany, Poland, Russia, and the Soviet Arctic.”

“The Soviet Arctic!” Leonard called out.

I turned to look at him.

“I didn’t think,” he said, hunching closer, “that the Russians allowed anyone to go up there.”

“They said I was the first journalist.”

“And you were writing for whom?” he asked.

“The New York Herald Tribune.”

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-four.”

“And how old were you when you wrote your essay on Virginia?”

“Twenty.”

Virginia seemed not to be listening, drifting off, when her housekeeper Lotte entered with a tray of teacups. She handed me one, but I put it on a small table next to me. I was afraid my hands would tremble and I would drop the cup. Virginia sipped her tea gracefully and began to speak again.

“We were just in your Germany,” she said.

Why did she call it my Germany? True, the thesis had been published as a trade paperback by the Tauchnitz Press in Leipzig. The publishing house, then 100 years old, was famous for printing the books of English and American authors such as Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf, all for tourists who could not read German and wanted to read a good book while traveling. To be sure, I had sent her my first letter in 1931 while I was a student at Cologne University. But I had sent the published book from my home in Brooklyn in 1935. She had sent her answer to me in Brooklyn, and I had spoken with a New York accent.

“We were driving through Bonn, on holiday,” she said. “Our car was stopped to let Hitler and his entourage pass.”

From her diary of April 2, 1935, I later read her impressions as she watched the Nazi convoy:

Hitler, very impressive, very frightening. … No ideals except equality, superiority, force, possessions. And the passive heavy slaves behind him, and he a great mould coming down the brown jelly.1

In her parlor, puffing her cigarette, Virginia Woolf shook her head, still talking of Germany.

“Madness, that country. Madness.”

I felt I could talk comfortably about Germany; I had lived there from 1931 to 1932.

“When I was an exchange student in Cologne,” I said, aware that Leonard was moving his chair closer to me, “I went to a Hitler rally held in a Messehalle, a huge hall near the Rhine. The family I lived with was terrified that I might be arrested, but I was determined to find out what that madman was really like.

“There were guards and soldiers everywhere, but no one stopped me and I entered the hall with trepidation. I found a seat in a half-filled balcony near the stage. A brass band struck up marching music as, within minutes, the hall filled up with an army of stormtroopers in brown uniforms and heavy black boots, marching and waving flags with swastikas.”

I paused. Had I talked too much?

Leonard moved his chair closer, as Virginia took the cigarette holder out of her mouth. I went on:

“The crowd went wild when Hitler entered and goose-stepped to the podium, followed by his entourage. The audience shouted, screamed, some applauded, others wiped their eyes in rapture. My heart was beating so loud, I thought one of those SS men would surely hear and maybe throw me out. But no one approached me.

“The moment Hitler raised his right hand in salute, the band stopped playing, the stormtroopers stopped marching, the flags stopped waving. Hitler’s worshippers stood frozen.”

Leonard nodded, as if to encourage me to go on. Virginia had still not resumed smoking.

“Hitler,” I said, “was ranting against the Weimar Republic, ranting against America, and mostly against Jews. It was a hysterical voice that seemed to come not from his throat, but from his bowels. Terrifying.”

“He has a terrifying voice,” Virginia agreed. “There is such horror in the world.”

I took up courage to say more.

“Hitler’s stormtroopers are now burning books in the university courtyard.”

I wondered if they were burning a copy of the paperback book I had sent her.

“What strikes me so forcefully in your books,” I said, “is the hope that women will help end the horror and create peace. Men make wars, not women.”

“Once,” she said, “we had such hope for the world.”

The words rang in my head. Such hope for the world.

I stood up. Half an hour had passed. I knew I should not take more of her time. I bent over and shook her hand.

“Thank you so much. Your writing gives me the will to write as a woman.”

She nodded, “Thank you.”

Leonard took my arm and led me out into Tavistock Square.

I returned to my hotel and swiftly jotted notes in my notebook, though I needed no notes to remember this day. I would remember it all vividly for the rest of my life. I was in rapture. I had met Virginia Woolf.

It was late October 1935 when I left London and sailed home on the SS Normandie. In the busy New York harbor, I looked around the pier. No one was there to meet me. I guessed my family was getting used to my comings and goings. I tossed my suitcase into the trunk of a yellow cab, and in the taxi’s back seat clutched my camera bag and checked my briefcase to make sure that my notebooks and the Virginia Woolf book were all safe.

Driving through Manhattan, then across the Williamsburg Bridge to Brooklyn, I kept breathing the air. Free air. Everything seemed peaceful, serene. The crowded streets seemed purely American with pushcart sellers selling fresh vegetables, while other vendors shouted, “Bargains, everybody. Come get your bargains here,” as they pointed to the housedresses hanging from racks. The dark shadow of war had not yet crossed the Atlantic.

I had scarcely rung the doorbell on Harmon Street when Mama opened the heavy black gate, kissed me, and said, “You must be starving.”

“Not at all.”

“Come in the kitchen anyway.” Mama, in a starched white apron, hurried me inside. “I prepared a whole meal for you.”

To Mama, food was love. I knew I was home.

In the sun-filled kitchen-dining-living room, Papa sat at the head of the table, waiting for me. I kissed him as he put his arm around me. “Thank the Almighty you’re safe,” he murmured. I took my favorite seat at his right. Mama was already filling our soup bowls with hot chicken noodle soup; and then she sat down to join us.

“We were so worried about you,” Mama said, “when we got your letters from Germany, Poland, Russia. All you hear on the radio is Hitler with that little mustache. He looks like Charlie Chaplin. Who goes to those countries now? Nobody. Only my mishuggeneh [crazy] daughter.”

She looked at Papa to make sure he agreed. He said nothing but smiled at me. Mama went on, “My aunt Mirel in Poland wrote us you left a lot of your clothes with her granddaughter Hannah.”

“I wish I could have brought her to America. She’s fifteen. In a couple of years, they’ll marry her off. What future does she have?” I turned to Papa. “What future did you have in Odessa?”

Papa stroked his white mustache for a minute. “I had to leave Odessa,” he said, “when I was sixteen. That’s when the police picked you up, put you in the army, and nobody ever saw you again.”

I decided it was safe to tell them something I had never written about to them, knowing how worried they would be. “In your shtetl, Mama, I was sitting with all your relatives who wanted to know about everyone in America until two o’clock in the morning. Suddenly two Polish policemen came banging on the door. One of them, a fat one, said, ‘We hear you have somebody from America.’ He pointed a club at me. ‘Open your bags.’ I opened my suitcase and watched him silently holding everything, even my panties and bra, up to the candle light. Then he went into my briefcase, opened every book, even a copy of my Virginia Woolf book, and shook them all.”

“Those police can’t read, can they?” Mama looked defiant.

“Certainly not English. I was worried they might take my notebooks with all my notes. But they left the notebooks alone. I must have looked very suspicious to them, especially carrying a typewriter and a camera. They told me to get out of Poland by morning or I’d be arrested.”

“What I was always afraid of,” Mama sighed.

“Your Aunt Mirel looked shaken. ‘You must go right now,’ she said. ‘You don’t know what they can do to you, arrest you, maybe, God forbid, kill you.’ Mirel’s son Yankel put me in his wagon, covered me with straw up to my neck, and made his poor old horse go faster and faster until we got to Warsaw.”

Papa put his head in his hands. “That was Poland? What happened to you in Germany? We read every day that hundreds of Jewish men are thrown in concentration camp. Jews can’t work. Even Jewish judges can’t sit in court any more. Jewish children can’t go to school. You weren’t scared?”

“It was scary sometimes,” I admitted. “Hitler has been in power almost three years and the country is completely changed. Completely Nazified. But there were some very brave people, real fighters. I went to see a woman in Berlin, a Jewish social worker. She kept looking out the window, to make sure the SS didn’t see me enter her office. ‘My daughter is your age,’ she told me. ‘She can’t get out. No visa. No country wants us. Go home and scream. Go home and scream in America what Hitler is doing to us.’ ”

The kitchen-dining room fell silent. A thought flashed across my mind. We’re three thousand miles away from Virginia Woolf. Except for mentioning my book about her, we haven’t said one word about her. We were fixated on the terrible news from Germany.

“What did Hitler do to your friends?” Mama persisted.

“I found a few of them. They all had to leave the university. One told me his Ph.D. thesis was stolen from his locker. It was his only copy. He’s desperate to get out of Germany. But the lines are so long with people trying to get out.”

“Master of the Universe,” Mama said, looking up to the heavens. “He took care of you.”

I didn’t sleep well that night. Images of Virginia Woolf in front of her fireplace, Leonard hunching over to hear about the Soviet Arctic, the talk about Hitler’s terrifying voice all kaleidoscoped in my head. Long past midnight, I finally fell asleep.

The next day, I called on Helen Rogers Reid, the wife of the New York Herald Tribune’s publisher Ogden Reid, and George Cornish, the senior editor. They were not interested in my interview with Virginia Woolf. “Ruth,” Helen Reid said, “we want to hear about your trip to the Soviet Arctic. You know you scooped the world.”

George Cornish nodded. “We want you to write a series of four articles on your experiences up there.”

The articles were syndicated and then appeared full-page four Sundays in a row, with the photos I had taken. The Trib received a score of letters, but none of them meant as much to me as Helen Reid telling me I’d scooped the world.

Virginia Woolf began to recede from my mind when Max Schuster, head of Simon and Schuster, asked me if I had enough unpublished material to write a book on the Soviet Arctic. I could hardly believe my luck when I signed the contract. I realized how timely such a book could be. War was in the air. The Arctic, at the top of the world, would soon serve as the shortest distance between the continents. Planes from New York, Chicago, and California could fly across Alaska to the Soviet Arctic, then across eleven time zones to Moscow, bringing butter and guns. A book I had planned to write on women in a changing world would have to wait until I finished this one.

I Went to the Soviet Arctic was published on September 1, 1939, the very day Hitler’s tanks and trucks and armies blasted into Poland. The war in Europe had begun. Virginia Woolf and the book on women were relegated to the drawer in the filing cabinet where the three letters written in 1935 and 1936 would be found almost seventy years later.

My life now revolved around the war and refugees fleeing from Hitler. I was determined to try to help them. But how? I was helpless, frustrated, angry. There were frightening rumors that Hitler was murdering whole villages of Jews in Poland. If only we could rescue them, snatch them from Hitler’s clutches. Were our own relatives in danger? What was happening to Hannah? Papa sent money for her older sister to go to Eretz Israel—the Land of Israel, the Holy Land. Her parents sat the seven days of mourning for her, weeping. They were sure the Arabs would cut her throat. Later we learned that she was the only one in the family who survived the war.

The United States was still not at war, though most of Europe was burning. Refugees were running across the face of Europe, trying to flee Hitler and his bombs and hordes of soldiers.

Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941—a date of infamy, our president called it. Now we were fully at war. There were thousands—no, tens of thousands—of Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s armies. But America’s doors were shut. We saved famous people—Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger.2 But the so-called “common people,” though they were not really common at all, were barred.

Virginia Woolf receded even further into the back of my mind, and, after her suicide in 1941, with no new books or essays appearing, she receded in the minds of others in America, and in England. American and British feminists rediscovered her in the ’60s and ’70s. Books and articles about her began to appear.

Dr. Deborah F. Stanley, president of SUNY Oswego, told me one evening how Virginia Woolf influenced her life. “She was really seminal in my awakening to the importance of feminism. It was in the seventies. I was at Syracuse University and formed a women’s reading group. We were four young women who sat around evenings discussing Virginia Woolf and exploring our souls.”

I learned what I had not known while writing my dissertation: she suffered severely from manic depression (the disease is now called “bipolar disorder” by scientists and psychiatrists). One of its manifestations is the tendency to suicide. In 1940, as Nazi planes were bombing Britain, she asked Leonard to buy poison for both of them. She knew that if the Nazis invaded England, Leonard, as a Jew, could be arrested and even murdered. London was on fire.

Virginia, tired, ill, seeking shelter from the nightly incendiary bombs, was ready to give up. She confided cryptically in her diary on May 15, 1940, “If England defeated: What point in waiting? Better shut the garage doors.”

Nor had I known that twice, in deep depression, she had tried to commit suicide. When she was very young, she kept hearing birds singing in her head in Greek. In 1941, at 59, she put stones in her pockets and walked into the river Ouse.

The time I had spent with her and Leonard was apparently one of her better days. She seemed neither manic nor depressed, but vitally alive. By a strange coincidence, not knowing that Virginia suffered from bipolar disorder, I had written repeatedly in my thesis about the polarity of her writing.

“A law of polarity, of conflicts as irreconcilable, as endless as night and day, reverberates through all of Virginia Woolf’s writing and reaches ultimate expression in The Waves,” as I wrote in my essay.

Even in her struggle for a style, she describes swinging from doubt in herself to “an ebb and flow of self-confidence, of doubt, of attempted change, and grim resolution.”

The odyssey of how I met Virginia Woolf, and how her life and work became intertwined with my life as an exchange student in Germany, began, oddly enough, when, in the autumn of 1926, at fifteen, I entered New York University and took my first course in German. Already a lover of Beethoven and Bach, I spent my undergraduate years learning more about the land and the culture that had produced them, and the language they spoke.

Ending my sophomore year, I spent the summer vacation in a six-week German program at Mount Holyoke College. The program was filled with American professors of German who came as students and who, despite my denials, were convinced that I was the granddaughter of Franz Gruber, the author of “Silent Night, Holy Night.”

English was verboten—prohibited. We ate, studied, sang, talked, and, I swear, even dreamed in German. Often, after morning classes and a hot New England lunch, I climbed a hill and shouted German poetry into the winds. German became my second language, and it was to be my mainstay when I brought a thousand refugees to America in 1944. German was the lingua franca of central Europe.

After spending another summer at Harvard, this time studying Shakespeare, I had enough credits to graduate from NYU, in three years. My philology professor, Dr. Ernst Prokosch, suggested that I apply for a fellowship to the German Department at the University of Wisconsin. Prokosch’s name on a letter of recommendation was magic. Within weeks, a letter arrived from Wisconsin:

“We congratulate you on being selected for the LaFrentz Fellowship in the graduate program of the German Department. You will receive full tuition and a stipend of $600.”

I was elated. Fellowships were one of the ways students survived during the Depression. In August 1929, I left for Madison, Wisconsin, planning to hitchhike the whole way. Instead of trying to stop me, Papa was so proud that he took me to his service station to get maps of the best route. No one worried. The roads were full of students holding up signs such as “CHICAGO HERE I COME” or “LA OR BUST.” Hitchhiking in those days was safe and fun. Truck drivers, often lonely on long drives, were glad to have someone to talk to. My one mistake was landing in a whorehouse in Troy, New York. One of the girls, in a tight-fitting blue satin dress and high-heeled blue satin shoes, stared at me in my brown oxfords and white socks, my blue skirt and white blouse. I looked more like a fifteen-year-old than eighteen in that outfit.

“Hey, kid,” she said, “what are you doing here?”

“I’m on my way to college in Wisconsin.”

“Well, you better get out of here fast. This is no place for you.”

That one year from 1930 to ’31 in Wisconsin was a year of stretching, of walking along the shores of the beautiful lakes, trying to discover who I was, making new friends, and writing my masters’ thesis in the German Department on Goethe’s Faust.

While in Wisconsin, I applied for a second grant, this time to travel to Germany, given by the Institute of International Education, known by the letters IIE.

The letter telling me I had won the fellowship and could study in Germany from 1931 to 1932 arrived during Easter vacation. I decided the news was too good to tell my parents by phone, so I hitchhiked home. Impatient after a full day, I decided to take a train from Albany to Manhattan’s Penn Station. I telephoned our housekeeper, telling her to ask my parents to meet me.

I learned later that in the Studebaker, driving from our house in Brooklyn to Manhattan, Mama asked suspiciously, “Dave, why is she coming home now? She didn’t even come home for Christmas. I tell you, she must be pregnant.”

Papa, who never lost faith in me, tried to reassure her. “Wait. We’ll find out soon enough.”

At the station, I flung my arms around them. “Guess what,” I could hardly control my excitement, “I’m going to Germany!”

Mama shook her head. “I wish she was pregnant.”

Unlike their pride in the Wisconsin fellowship, this exchange fellowship to Germany was a nightmare for them. They did their best to prevent me from going. They offered me a car. They offered me the equivalent in money. Mama was sure that Adolf Hitler, who was not yet in power in 1931 but was in the news almost every day, would come off a stage and shoot me.

“He won’t shoot me, Mom,” I told her. “I’ll wear a pin with an American flag on my lapel and I’ll carry my American passport in my blouse.”

Mama, sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued, said, “And Hitler can’t shoot through a passport?”

I told my father, “Papa, you knew at sixteen it was time for you to leave Odessa. You knew you had to get out of Czarist Russia. I know it’s time for me to go to Germany. I want to find out what Hitler is up to.”

Though I knew how anxious they were, I had the money in my pocket. Restless to get out of Brooklyn and begin my journey, I gave myself the whole summer to travel through Europe. The classes in Cologne would start in late September.

Seeing me off on the S.S. Milwaukee of the Hamburg-Amerika Line, Mama wept. “I don’t know if we’ll ever see you again.”

“You will, Mama. It’s only for one year.”

She acted as if she were already sitting in mourning.

It was June 1931 when I arrived in Paris and spent a month taking morning classes at the Sorbonne and whiling away my afternoons sipping tea at the Metropol Café, hoping to see some of the American writers in exile, especially Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. I never saw them, but I was thrilled, telling myself the world was opening up for me.

London was next. I took my first airplane ride from Paris to London. I felt like an adventurer. I was exploring two cities I had grown to love from books. I was also exploring myself, a nineteen-year-old who had grown up in the cocoon of a loving Jewish family, yearning to break free, yearning to embrace the world. I was happy to travel alone so that no one diverted me from meeting new people and marveling at the beauty of these two cities. Elsewhere in England, I wandered through Oxford, visited Stratford where Shakespeare had lived, and breathed the literary air of England so that Charles Dickens’s novels and Wordsworth’s poetry came alive to me as never before.

From London I took a train and ferry to Holland, sat on its beautiful beach at Scheveningen, watched Dutch women walk in wooden clogs, and finally arrived in Cologne on a balmy September day in 1931.

Dr. Hugo Gabriel, thirtyish and effervescent, representing the IIE at the University, had found a Jewish home for me with Papa Otto and Mama Frieda Herz and their daughter Luisa, my age. They treated me as if I were their second daughter.

For some reason, as soon as we met, Dr. Gabriel told me that his parents were Jewish, but he was Protestant. Hitler was not yet in power, but some Jews, fearing his virulent anti-Semitic threats, sought to save themselves by converting. I did not feel that I had the right to ask him why he had abandoned his Jewishness.

He helped me choose the courses I would take. We agreed that I would attend classes in German Philosophy with the renowned Nietzsche scholar Ernst Bertram; “Englisches Seminar”; and art history.

I had been at the university for about a month when Professor Herbert Schöffler, a round, fatherly-looking, middle-aged man, head of the “Englisches Seminar,” called me to his office.

“We have been watching you,” he said. “We would like you to stay and work for a Ph.D.”

A Ph.D.!

I shook my head. “My parents would never give me money to stay for another two or three years—or however long it takes to get a Ph.D. in Germany.”

“Nobody,” Professor Schöffler was smiling, “nobody in Germany has ever gotten a doctorate in one year. But maybe you can do it. I have a special reason. I love Virginia Woolf’s writing. None of my students knows English well enough to analyze her writing. You are the only American student here. I would like you to write a dissertation—in English—analyzing her work, her style, her language.”

I managed to say “I’ll try,” shook his hand, and rushed downtown to my favorite bookstore. There they were, all of her novels published to that point, including her latest, The Waves, all in English, all in paperback, all published by the Tauchnitz Press.

I was soon mesmerized by Virginia Woolf’s writing. I hung her picture on my bedroom wall. A Room of One’s Own became my Bible. It gave me the courage to later dispense with the objective journalist’s voice and write from my heart and soul. I was fascinated by her will to write as a woman, and distraught by her anxiety and fear that male critics would tear her books apart. She was on the side of the creators, the dreamers, the poets, the women. On the other side were the critics, the predators, the destroyers, the angry, hostile, women-loathing men.

She wrote Orlando, my favorite of her novels, as an ode to Vita Sackville-West, one of the women she loved. In a sense, the character “Orlando” was physically bipolar—a charming and heroic man who metamorphoses into a charming and beautiful woman.

In one of my sessions with Professor Schöffler, I told him how much I was enjoying Woolf’s writing and how much more I wanted to know about her.

“Very good,” he said. “Why don’t you write to her, care of the Hogarth Press?”

He checked his files and gave me the address, “52 Tavistock Square, London, W.C.1, and here is her telephone number, Museum 3488.”

I wrote a letter which included some questions about her work and, a few weeks later, received an answer from her secretary, Peggy Bolsher.

16th Dec 1931

Dear Madam,

… Mrs Woolf has always preferred to let her readers decide for themselves as to the meaning of her books, and therefore can not reply to your questions as to the autobiographical elemkent [sic] in Orlando; but it is generally known that the story is based, so far as it is based on reality, on the life of Miss Sackville West; and the house is underatood [sic] to be Knole, the home of Miss Wests [sic] ancestors in Kent.

Yours faithfully P. Bolsher (Secretary)

During the Christmas vacation, I took some of Virginia Woolf’s books with me on the train to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s favorite vacation town. I was with four other American exchange students, each of us invited by the U.S. State Department to spend the holiday together at a ski lodge. A State Department official greeted us as we entered the lodge, told us he was in charge and that if we had any problems, we were to come to him.

He told us to meet for dinner at 6 P.M. in the ski lodge. Five townspeople were our hosts, all jovial-looking, the women in brightly colored dirndl skirts and starched white blouses, the men in knee-high leather pants, leather vests, plaid shirts, and green felt hats with feathers darting up from the brim. I was placed next to a robust, red-faced peasant in his mid-twenties. After he had drunk several beers, he became a little too friendly, putting his arm around my waist.

“You’re different, even though you’re an American,” he said to me in German. “I don’t like Americans, and I hate Jews.”

I pulled his arm away, stood up, and said, “I am an American, I am a Jew, and I will not listen to anyone denouncing my country and my people.” I stalked out.

The State Department official rushed after me. “You insulted him. I want you to go back and apologize.”

“I apologize to someone who denounces America and Jews? He should apologize to me.”

The State Department official’s face flushed with anger. “This is no way to treat our host.”

“Then I will leave here in the morning.”

Back in my bedroom, freezing with cold, I asked for hot bricks for my feet. They were poor comfort for the anger I felt that a U.S. governmental official would defend an obvious Nazi. True, I was his guest, but I did not have to submit to a Nazi insult. I was angry too that the official was more concerned with proper manners than with racial slurs.

I packed my clothes and my Virginia Woolf books the next morning and took a train to Vienna, where a friend of my sister Betty was studying medicine.

“What would you like to see today?” he asked me.

“I’d like to the see the university where you’re studying.”

“I don’t think you’re going to like what I have to show you.”

“Why?”

“You’ll see.”

We entered the lab; broken glass lay strewn on long tables and on the floor.

“Nazis came in here yesterday,” he told me, “and broke every one of our experiments. Months of work ruined.”

“It’s horrible,” I said. “How can you go on studying here?”

“I have no choice. I couldn’t get into a medical school in the States. They all have quotas limiting the number of Jewish students. I was lucky to be accepted here, and I’m going to stay.”

I left Vienna, rushed back to Cologne, and continued working on the dissertation while attending courses on Nietszche, modern English literature, and Albrecht Durer in art history. At the same time, I followed the results of the German elections that were taking place every few months. The greatest lesson I learned in Germany was how one can become a dictator legally. Hitler entered every election and won nearly all of them until he reached the top and overthrew the government.

In the summer of 1932, I handed Professor Schöffler my thesis, “Virginia Woolf: A Study.” A few days later, I would take the oral examinations. Three examiners—Professor Bertram, Professor Schöffler, and a professor from the art department—sat on chairs in a circle in Bertram’s office, like inquisitors in an interrogation chamber. One of my Jewish friends in the university had told me that Professor Bertram hated Jews, hated Americans, and hated women. But he was a charismatic teacher who had taught us enthusiastically about what a great philosopher Nietzsche was.

Stories of how many students Professor Bertram had failed in their orals flashed through my brain. German students could take them over and over, but if I failed, it was the end for me.

I stood before the three men, my hands cold as ice. Professor Bertram, speaking in German, began the ordeal with questions about Nietzsche and his philosophy.

“What stands out most for you in Nietzsche’s philosophy?” he asked.

I tried to control my teeth from chattering,