1. The Greyhound

2. The Magician of the Toodoggone River

3. Outward Bound

4. Isn’t Life Wonderful

5. A Devilishe Pastime

6. Niagara

7. A Grey Hair in God’s Eyebrow

8. “Really, Serving Mother Gettle’s Soup Is Lots Simpler”

9. Called to the Bar

10.The Hound of Heaven

11. Eridanus

12. Niagara-on-the-Lake

13. The Tides of Eridanus

14. A Bottle of Gin

15. Isn’t Life Wonderful

16. Lake of Fire

17. A House Where a Man Has Hanged Himself

18. The Element Follows You Around, Sir!

19. Fire Fire Fire

20. The Wandering Jew

21. Go West, Young Man!

22. “A Little Lonely Hermitage It Was…”

23. Adam, Where Art Thou?

24. “The Wretched Stalking Blockheads—”

25. But Still the Old Bandstand Stands Where No Band Stands

26. “…Stalked Fatefully…”

27. Useful Knots and How to Tie Them

28. Wheel of Fire

29. Just Behind the Bastion

30. The Ocean Spray

31. Twilight of the Raven

32. Twilight of the Dove

33. The Dock

34. Outward Bound

35. The Perilous Chapel

36. Not the Point of No Return

37. Uberimae Fides

Editor’s Note

A Biography of Malcolm Lowry

It is an old story, that men sell themselves to the tempter, and sign a bond with their blood, because it is only to take effect at a distant day; men rush on to snatch the cup their souls thirst after with an impulse not the less savage because there is a dark shadow beside them for evermore. There is no short cut, no patent tram-road, to wisdom: after all the centuries of invention, the soul’s path lies through the thorny wilderness which must be still trodden in solitude, with bleeding feet, with sobs for help, as it was trodden by them of old time.

GEORGE ELIOT: “The Lifted Veil”

Al stereless with-inne a boot

am I

A-mid the see, by-twixen windes

two,

That in contrarie standen

ever-mo.

CHAUCER: Troilus and Cressida

I wish to express my thanks to William C. McConnell, barrister, solicitor, and friend, for his help in all the legal matters in this book.

M.L.

FAREWELL, FAREWELL, FAREWELL, EIGHT Bells, Wywurk, The Wicket Gate. The little house looked all right. So we love forever, taking leave.

The October morning sunlight filled the swift bus, the Greyhound, sailing through the forest branches, singing straight out to sea, roaring toward the mountains, circling sudden precipices.

They followed the coastline. To the left was the forest; to the right, the sea, the Gulf.

And the light coruscated brilliantly from the windows in which the travelers saw themselves now on the right hand en-islanded in azure amid the scarlet and gold of mirrored maples, by these now strangely embowered upon the left hand among the islands of the Gulf of Georgia.

At times, when the Greyhound overtook and passed another car, where the road was narrow, the branches of the trees brushed the left-hand windows, and behind, or in the rearview mirror ahead reflecting the road endlessly enfilading in reverse, the foliage could be seen tossing for a while in a troubled gale at their passage. Again, in the distance, he would seem to see dogwood rocketing through the trees in a shower of white stars. And when they slowed down, the fallen leaves in the forest seemed to make even the ground glow and burn with light.

Downhill: and to the right hand beyond the blue sea, beneath the blue sky, the mountains on the British Columbian mainland traversed the horizon, and on that right side too, luminous, majestic, a snowy volcano of another country (it was Mount Baker over in America and ancient Ararat of the Squamish Indians) accompanied them, with a white distant persistence, and at a different speed, like a remote, unanchored Popocatepetl.

“Well, damn it,” he said, “I don’t think I’m going to.”

“Not going to what, Ethan sweetheart?”

Ethan and Jacqueline sat, arm in arm, in the two back left-hand seats of the Greyhound and once when he saw their reflections in the window it struck him these were the reflections of some lucky strangers who looked too full of hope and excitement to talk.

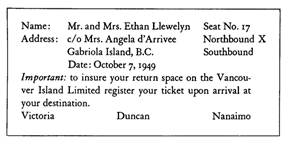

“Register our tickets at the depot to insure return space. It seems to be tempting fate either way you look at it.”

Jacqueline smiled at him with affection, absently, patting him on the knee, while Ethan regarded their ticket again.

Victoria…Duncan…Nanaimo hath murdered sleep.

And in Duncan too, the poor old English pensioners, bewhiskered, gaitered, standing motionless on street corners, dreaming of Mafeking or the fore-topgallant studding sail, or sitting motionless in the bankrupt rowing club, each one a Canute; golfing on the edge of the Gulf, riding to the fall of the pound; bereaved of their backwaters by rumors of boom. Evicted…But to be evicted out of exile: where then?

The bus changed gear, going up a hill: beginning: beginning: beginning again: beginning yet again: here we go, into the blue morning.

The vehicle was rounding a high curve and as it turned down toward the valley below, Jacqueline leaned forward for a better view from the right-hand windows: the sea swarmed with islands, and one of them was surely Gabriola.

Gabriola! Ah, if it should prove the right place, her eyes were saying, the dreamed-of place, and the old skipper’s house Angela had written about still for sale, and, more important, within their means to buy! Of course, there was this other “lot” they could almost certainly get, but then they’d have to build a house, and that would take so long.

For the Llewelyns, like love and wisdom, had no home.

Jacqueline, he knew, already saw the skipper’s house as theirs, as their home. Small, but with big sun-filled seaward windows it stood for her, facing the Pacific and the blue mountains of the mainland, while behind, it was guarded by a forest of huge knotted maples and firs and ancient cedars and, against the sky, tall slender alders, swaying…

She had a passion for gardening, so for her a garden was all-important. But also the wide verandahs, big cupboards, a stone fireplace: all these delightful (and to Ethan, after their life on the beach in Eridanus, by now almost irrelevant) possibilities, combined with other “conveniences” not long since all but forgotten, would be taking shape in her mind, just as they had no doubt many times taken shape in her mind this last unhappy month of loss and searching—only for her to be confronted by the reality of bare treeless grassless yards, soulless desiccated war-built bungalows, or older houses yet more moribund, for the awfulness of having to live in which no “conveniences” whatsoever would even compensate, homeless homes with stoves full of old bones, and subaqueous basements, neglected and run down during the last years, houses once well situated, but now viewless as Shakespeare’s winds, cackling, who knows, with poltergeists.

Yet this time, she would be thinking, ah this time it would be different, for surely a skipper of all people would be one to have rendered his own house shipshape, even if a retired skipper. As if shipshapeness were the entire question with her either.

Gleaming white cedar siding home

Clean as a pin from stem to stern.

Living room, dining room, kitchen with Sun room off. And two bright bedrooms.

It was an ironic little chant they had. At this point they would always pause and then add in unison, laughing: “Only ten thousand dollars down!”

ETHAN LLEWELYN WAS SHARPLY reminded that he himself was “retired,” and that his total income now amounted to not much more than $10,000 in two years. He was in an income tax bracket more compatible with the role of public defender he had so often, to his credit and the detriment of his pocketbook (Ethan was really thinking in this peculiar manner), assumed in the past, and for which he was still even nationally famous. A prosperous criminal lawyer, despite this, he had, though still a fairly young man, given up practice two years and four months ago, three summers and two winters, after one of the most gruesome and complicated cases he had ever defended. Well, it was not exactly retirement. Nor had he made the move because he’d lost this particular case: in part it was perhaps because, having for so long sincerely believed his client, a deceitfully benign watchmaker, innocent (and such was Ethan’s genuine train of thought), it had only been to discover, after he’d saved him from the scaffold, locally in this instance a disused prison elevator shaft painted bright yellow, that he could not have been more guilty.

With means, if more than a little diminished means, of his own Ethan had done what his father before him, likewise a lawyer, had done, and had once in days past counselled him to do before it was too late, before this might spell an irrevocable retirement. He made a “Retreat.” (To be sure he had not been bidden so far afield as had his father, who’d spent the last year of peace before the First World War as a “legal adviser on international cotton law” in Czarist Russia, whence he brought back to his young son in Wales, or so he announced, lifting it whole out of a mysterious deep-Christmas-smelling wooden box, a beautiful toy model of Moscow; a city of tiny magical gold domes, pumpkin- or Christmas-bell-shaped, sparkling with Christmas tinsel-scented snow, bright as new silver half-crowns, and of minuscule Byzantine chimes; and at whose miniature frozen street corners waited minute sleighs, in which Ethan had imagined years later lilliputian Tchitchikovs brooding, or corners where lurked snow-bound Raskolnikovs, their hands stayed from murder evermore: much later still he was to become unsure whether the city, sprouting with snow-freaked onions after all, was intended to be Moscow or St. Petersburg, for part of it seemed in memory built on little piles in the “water,” like Eridanus; the city coming out of the box he was certain was magic too—for he had never seen it again after that evening of his father’s return, in a strange astrakhan-collared coat and Russian fur cap—the box that was always to be associated also with his mother’s death, which had occurred shortly thereafter; the magic bulbar city going back into the magic scented box forever, and himself too afraid of his father to ask him about it later—though how beautiful for years to him was the word “city,” the carilloning word “city” in the Christmas hymn, “Once in Royal David’s City,” and the tumultuous angel-winged city that was Bunyan’s celestial city; beautiful, that was, until he “saw” a city—it was London—for the first time, sullen, in fog, and bloodshot as if with the fires of hell, and he had never to this day seen Moscow—so that while this remained in his memory as nearly the only kind action he could recall on the part of either of his parents, if not nearly the only happy memory of his entire childhood, he was constrained to believe the gift had actually been intended for someone else, probably for the son of one of his father’s clients: no, to be sure he hadn’t wandered as far afield as Moscow; nor had he, like his younger brother Gwyn, wanting to go to Newfoundland, set out, because he couldn’t find another ship, recklessly for Archangel; he had not gone into the desert nor to sea himself again or entered a monastery, and moreover he’d taken his wife with him; but retreat it was just the same.)

“It is a course the wisdom of which should not be impugned because its objectives, briefly, may often be expressed only in clichés,” his Scottish father-in-law, a not unexpected ally, had observed in his solemn oratorial burr. Ethan smiled to himself; the thought of Jacqueline’s father, when he could bring himself to believe in the existence of such a man on earth at all, afforded him keen pleasure. The British Isles beget bizarre sons: and examples of her most fabulous were to be found in Canada. And if Canadian policy (as once with the strategy of the Battle of Britain) was never, according to reliable report, formulated by its higher ministers without recourse by its highest to counsel from the angelic host, and if there were, and their friend the gamewarden in Eridanus swore there were, Englishmen in British Columbia who lived up trees, why not a Scotsman in the Dominion of whom it was said, like Virgil, that he was a white magician? Fantastic though it sounded, Angus McCandless was or had been a cabbalist, and one of high degree, even a sort of Parsifal: this once accepted, if you like cum grano salis, his interior life seemed, to a layman, of a transcendent, an almost unapproachable seriousness, though he could discuss aspects of it with anything but seriousness; the humor of the situation entered for Ethan via the fact that the old practitioner of ceremonial magic was also a hard-fisted and tough rancher, farmer, ex-soldier (precisely how he squared his magical activity with his conscience Ethan had never understood, for The McCandless, besides having been a Mason, was also a Catholic). “Before the amassing of money, and in Canada the law is a method of making it appallingly facile,” The McCandless had gone on, “you may now consider your own, and my daughter’s deeper needs. You may now place health and the pursuit of happiness first, it being a providential thing that your grandfather saw fit to provide in his will for your son’s education. Aye. And I am profoundly glad that you are anxious to know yoursel’, to discover, if possible, other, profounder capacities in yoursel’. Perhaps after all,” he had added with unconscious sarcasm, “you are not essentially a lawyer, even if it is to be hoped you will never lose your affection for the paradoxes and absurdities of the law itself.” (Indeed Ethan still lectured occasionally—or had until these last months—on Canadian law, to the changing of which, in certain horrendous items, he yet hoped to contribute.) Another peculiar thing about Jacqueline’s father was that, a Scot of Scots, he had not been born in Scotland at all, but in Bordeaux, being directly descended from a Scottish laird who in the ancient days of Bordeaux greatness, was a knight-at-arms in the retinue of the Duke of Berwick, the son of James II and Marlborough’s sister, who once held there what approximated to a court-in-exile. One branch of the family had never left the old seaport, and it was on his own parents’ visit to these relatives that Angus McCandless had been born. Still half loyal in his heart to the victor of Almanza and the House of Stuart, The McCandless had emigrated to Canada after being informed that several original letters of Montesquieu, discovered in the family archives, were his property. These had been sold to the library of the Arsenal in Paris, though the proceeds didn’t get him very far. “As for me,” the old magician said, “my life has been full of retreats. In this country I started at eight dollars a month in 1905 on a stock farm working from daylight to dark. There was a retreat for you…The following year I got forty dollars a month breaking horses on a ranch in Saskatchewan. Then I rode herd on the Toodoggone River Ranch for twenty-five dollars a month and board. That’s two more retreats. In 1908 I took up a homestead sixty miles from Dumble, Alberta. I sold that for twenty dollars an acre after three years homestead duties, which was worse, on the whole, than the Montesquieu Letters. I went overseas in 1914, more in pity than in anger still faithful to Old England—the most unusual bloody retreat of the lot…I was invalided home with a leg wound in November 1917 and in February 1919 I bought a poultry farm at Onion Lake, where I lost heavily on account of the low price of eggs.”

Finally he’d bought another farm: “And I may say this was all bushland and took me nine years to pay for it working out, which was another retreat for you, and by then of course we had young Jacqueline to look after.”

ETHAN HAD MET HER one winter afternoon of thunder and snow in 1938 within the foyer of a suburban Toronto cinema, where they were showing Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., in Outward Bound. This was a merry euphemism; they had shamelessly picked each other up, a cause of much later laughter between them, since it was a movie house that showed “serious films for high-class audiences,” and it had struck them both simultaneously that this of course sanctified such giddiness. Slim and supple, dark-eyed, dark-haired, and incredibly young and passionate-looking—Ethan was not capable of more detailed asseverations in regard to women, as he explained it to her afterwards, her legs were so beautiful he felt as if he had swallowed a bolt of lightning—and lounging by the velvet curtains of the entrance, smoking a cigarette, she greeted him gaily and almost as if they were lovers already. Rouging her lips, she told him she prided herself on her independence, went everywhere unescorted if she felt like it, was a chain smoker, liked to drink gin and orange juice, loved good movies and taught school in an Ontario village: music, French, botany, literature, everything, and had twenty-two pupils.

“It’s a little school just outside Norway, about a mile off the main highway.”

“—Norway’s the town where we used to live part of each year, in Wales, on the Caernarvonshire coast.”

“My Norway’s just a little place east of Toronto.”

Ethan suggested that perhaps she’d consider him as her twenty-third pupil, and added that talking of twos, he’d left Canada when he was two, having been born here in Ontario itself, and hadn’t returned until he was twenty-two, which was six years before.

“And how do you find your native country after so long?”

“Big.”

She said that her father came from “the old land,” and Ethan, taking her cigarette and putting it out in the sand-filled trash stand, remarked that he’d returned largely because of the depression in order to help disentangle his father’s affairs in Canada.

“I feel lonely,” he said. “Everybody takes me for an Englishman and they seem to hate the English like the devil. Myself, I take pride in saying I’m English even though I’m half Welsh, even though strictly speaking I’m a Canadian.”

“I’m Scottish.”

“—but are we going to heaven, or hell?” the great voice of one of the characters in the show boomed through into the foyer…“Ah,” came back the answer, “But they are the same place, you see.” Had the voice been that of the Inspector, who was supposed to be God, who had come aboard that ship of the dead to judge the passengers? Or was it Scrubby the barman speaking, the “halfway,” destined because of his suicide to commute eternally on that spectral ferry between earth and the unbeholden land?

BUT FROM THE FIRST Jacqueline and Ethan had been completely at home with one another. They joined a film society showing film classics on Saturday afternoons in an auditorium—it turned out—belonging to the tuberculo-therapic annex of the General Hospital, where they went to see, for a start, D. W. Griffith’s Isn’t Life Wonderful.

Life might be wonderful, or seem so at the moment, but it hadn’t occurred to Ethan before that it could be provoked to actual mirth at the mere hint of death or dissolution…Yes, uncharitable as it was merely to entertain such a thought here, even in the absence, naturally, of the patients, Ethan and Jacqueline, seated almost alone in the stalls equipped with objects they at first mistook for ashtrays, every time they reflected on their environment vis-à-vis the title of the picture, found themselves, to their shame, beset by promptings to irreverence similar to those which sometimes tempt the kindliest folk to bizarre behavior at funerals. And for a few minutes they actually had a hard time stopping each other laughing out loud. Ethan soon discovered the film was impressing him deeply and in a new and strange manner in which he never remembered being impressed before. The scene was laid somewhere in the Balkans, and the film opened with two young lovers, newly married, being driven from their home, a hut on the edge of the forest, by looting soldiers who killed their parents and then set fire to their hut. Now the lovers were fleeing for their lives, dragging their sole remaining possession: a sack of potatoes. Behind them, distantly, their home burned. The day declined in the forest with a turbulent sky above the trees presaging storm, and the lovers, fearful of more soldiers, or bandits, did not know what path to take. Next, bandits ambushed them and robbed them of their sack of potatoes. Night fell. The defenseless lovers were lost in the forest. All was dark…The story thus far had the virtue of its own naïveté but also to their more modern eyes the film occasionally appeared so crude and jerky it was difficult not to laugh now for that reason. But quite suddenly Griffith’s genius began to transmute all this, and in such a profoundly beautiful way, Ethan felt it almost beginning to change something in himself. The camera traveled slowly up to the treetops bending in the wind and now you saw the tempestuous sky brighten as the moon sailed out of the clouds. And instead of giving way to despair as the lovers had seemed about to do, they gazed up with a hungry supplication at this wild beauty of trees and stormy moonlight above them, then turned to each other with love, as to say, a supposition confirmed by the subtitle, Isn’t Life Wonderful.

Ethan, who had his excuses, reflected he hadn’t often felt life was very wonderful—certainly not in that way. Still, he must have sometimes gazed at the beauty of trees or the moon or the sea—undoubtedly the sea—in much this fashion, in youth at least, though such yearning was always short-lived with him, short-circuited by embarrassment at himself, the foolishness of the girl he was with, by some feeling of general frustration, more often sexual, or a humble, obscure and complicated sense of ignorance, as from some lack of ratification for what one saw, which perhaps was not what one was supposed to see, or which was not all a finer nature would see. And how many times had not misery or loneliness, or when he grew older, guilt, even complete hopelessness, got in the way? Anyhow, this scene on the screen with the transfigured faces of the lovers gazing up at the moonlight falling through the treetops struck him all of a sudden as so much more poignant than anything he had ever experienced in fact, and seeing it with Jacqueline affected him with so much the more uninhibited wonder, that what happened was extraordinary. It was like deducing the real from the unreal. It was as though the moonlight falling through the trees on the screen inside the theatre, by the transpiercing beauty of the manner in which it was perceived and photographed, gave the remembered moonlight of the world outside a loveliness it had never before possessed for him, nay, gave the earth, life itself, for him, another possible beauty, a new reality somehow undreamed-of theretofore.

But now here was all this, and here he was, aware of Jacqueline’s moist hand in his, of both of them trying not to weep, but he could feel it happening by a perfect identity, they were the lovers themselves. Now they saw with the lovers’ eyes. It was they who, having lost everything, had not given way to despair. It was they themselves, Ethan and Jacqueline, who were gazing up now at this wild beauty of trees and stormy moonlight above them in rapture, and thanking God for their love, because life was wonderful and they were in love themselves and this was what it was to exist!

The film ended with a similar scene of trees in sunlight with the lovers approaching down a long road, hand in hand, gazing up at the over-arching treetops overhead, then there was only the long road stretching into the future…while the next moment Jacqueline and he were standing outside the cinema on a similar deserted road, one of the quiet tree-lined avenues adjoining the hospital grounds; beyond to their right they found a small park, where a few convalescents were walking or being wheeled by nurses, and where now, excited by the film and uncertain where to go (Ethan was still afraid of her youth, didn’t know where to take her, and perhaps was a little afraid of himself), they began to drift up and down, discussing the film. Ethan became so enthralled he scarcely knew after a time whether he was talking or simply thinking to himself. Not only was the film not sentimental, he decided, there was no irony in the title. It was, in a mysterious way, the truth, yes even in Keats’ sense. (Latterly Ethan, then almost totally ignorant of literature, unless rhetoric be a branch of it, but anxious to prove himself indeed Jacqueline’s twenty-third pupil, had taken to reading poetry, Jacqueline having started him off recklessly with Keats.) There was the beauty of truth within which was the truth of love, and the truth of beauty above, which love perceived through its own eyes, and to which it mysteriously corresponded. Something like that. So that if you had love, even if you’d lost all your worldly goods you simply spoke the truth when you said, “Isn’t Life Wonderful?”

Suddenly death appeared an enemy, the world (so different from the earth), not less so: then you were a great deal stronger than death too, if you had love, and faith in that love. Ethan waxed impassioned, derivative, contradictory, philosophically profound, personally adolescent. He also felt himself being very entertaining, in the manner of a lover who arouses gaiety with all the ardor of one making love, a gaiety in which, especially when remembered in later marriage, sometimes sounds a note of sadness, as though such moments foreshadowed not only the lightheartedness and companionship of that married life, but its pitfalls, sorrows and bereavements too…

As he was saying, only the earth with all its beauty was your friend, and the outward correspondence of your inner nature, when you were blessed with love. And if you betrayed this by too much attachment to the things of the world, love could only revenge itself by appearing in material guise too and bring about your downfall. And it was scarcely Ethan’s most logical or original argument for the defense, that that had started out on behalf of “life,” nor involved any point of view or law—whether jus civile, jus divinum, jus gentium, not to mention post liminium—he had ever formerly maintained or thought of maintaining. But certainly it was his most eloquent and persuasive speech, which (while rendering yet more untrue that sentence we read in the novel on our grandmother’s shelf: “Seldom can a proposal of marriage have veiled itself in terms calculated to seem less attractive to a beautiful young girl”) was no doubt more illogical under the circumstances than anything in it, and, as it proved for him, certainly his most important.

“Ethan, are you saying you love me?”

“Am I—I—”

“Would you do that for me?”

“…Would I do what—?”

“If we were driven out of our home into a forest with everything gang agley, and all our plans turned round in mid-air and thrown away in an old boot, and there we were with sweet damn all in the world, and everyone against us and nowhere to go, would you still look at the moon like that with me and say, ‘Isn’t Life Wonderful?’ ”

Ethan looked up at the moon through the trees which the ratepayers of this district had recently petitioned to have removed as a menace to life, and as old-fashioned eyesores not in keeping with the modern development of this fine section. It was the first time he had so passionately sided with the trees, even though he did not know what kind they were.

“Is that what you feel, Jacqueline?” Ethan, still looking up at the trees under a sky like an illuminated eiderdown, felt suddenly sorrowful and hopeless. “But I’m too old for you.”

Jacqueline put her arms around his neck and kissed him. “Aye, you’re a sad disappointment to me, with all your sorrow and gloom.”

“It’s because I’m so terribly in love with you.”

“Huh. I’ve known that for ages.”

They stood with their arms about one another. “Oh, I can see we’re going to be a terrible comfort to each other,” Jacqueline said wryly.

IT WAS SPRING AND they walked down the sidestreets toward a field where a game of English rugger was in progress and where, along its edge by the pavilion, near which Ethan had parked his car, trees were already in bloom. Bluebells and crocus and little wildflowers were blowing in the grasses here, and above the sun was shining. Grim Toronto was still a little town called York in this place. Ethan asked what sort of trees these were but Jacqueline seemed still in a strange mood induced by the film they had just seen, Wuthering Heights.

“I asked you about the trees?”

“Ah yes, the trees,” Jacqueline, who had been gazing, deeply abstracted, at the wildflowers, woke up again, and turning to him suddenly flung out her arm in a graceful dramatic gesture. “Cherry, peach, pear, my God, don’t you know that? Don’t you see anything? Except hildy-wildy films with me. And don’t you do anything, besides defend people charged with horrible crimes? I mean. Belong to any clubs, or anything? Don’t you know anyone?”

“Yes, I belong to a club, composed of other people who defend people charged with horrible crimes.”

They were watching the rugger game, Jacqueline rather listlessly, Ethan intermittently, and with some sardonic relish passing such un-Canadian judgments as “Jolly well tackled, sir.” Or “Drop a goal, why don’t you?” Or “Heel it out of that scrum.”

“If it matters, very few people outside my work. And if you want to know too,” he glanced about him at the gently tremulous pink-and-white snow of blooms on the trees among which the ball, the consequence of a wildly aimed drop-kick, was bounding erratically, and now, fielded by one of the dozen or so spectators at their end was returned with a heavily expert air, “this is the first time I’ve ever really seen a spring, this time with you, in my whole goddam life. And if you want to know why, it’s partly because I was blind, or almost blind, from the age of eight or nine to thirteen or thereabouts, so I never acquired the habit of looking at things, trees and flowers you see, or understanding what nature was about, and anyhow there was no one who cared to teach me…But perhaps you’d feel better if I told you I got sidetracked from an important brief last week reading those bits of Hardy and Burns you suggested…Wonderful. But it’s almost all a revelation to me. Almost all new…Back we go into touch—another line out!”

“Ethan, my poor darling!”

“I only told you partly to explain why I still have difficulty in reading, and understanding certain things. I just didn’t acquire the habit.” Later, he said, at the University, he took to law enthusiastically, “I think I can say because a lot depends on memory,” and he’d acquired an encyclopaedic memory of a narrow kind. Otherwise he’d also inherited from his childhood a capacity for concentration and wandering attention about equally extreme. “Anyhow, the way it’s worked out—though I won’t say I wasn’t read to, even my father read to me when he felt in a mood to listen to his own voice—and though I must have crashed through heaven knows how many libraries of law books by now, and even have some philosophical training—I’ve only read about half a dozen serious novels right through without skipping. Crime and Punishment…I read all that, including the epilogue…And I know something about music, and can even pretend to tootle on the clarinet like Mr. Goodman.” He said all this quite seriously, looking down at Jacqueline, who made sounds both soothing and admiring.

“But poetry, ancient and modern, was almost absolutely a dead issue with me till I met you, and art, in the sense of painting, is totally beyond my knowledge. I secretly believe the world is flat, and have such godawful difficulty working out my income tax it’s come to be a standing joke with the income tax department…Well, I’m partly joking now…Take a breathah, you fellows! Or let that bloody ball out to the threes—” He turned back to her. “At least this isn’t illegal any more, or considered a ‘devilishe pastime which led to brawling, murther, homicide, and great effusion of blood.’ Though can’t you just see a Toronto Leet Roll ban after the pattern of the Manchester one three centuries ago ‘because of great disorder and the inhabitants charged with makynge and amendynge of their glass windows broken by lewd and disordered persons playing with the foote-ball…’ I have a lot of apparently useless knowledge like this. I find it invaluable in court.”

Jacqueline was laughing. “But you seem to know a lot about this game.”

“…that bit was cheating, really. It sounds as if I’d been making esoteric legal researches but actually I got it out of the Manchester Guardian. Besides, it strictly pertains to soccer. I played rugger for three and a half years at an English public school and got to like it a lot, though I never was much good. I had plenty of time to transcend it all, but maybe the damage was done.”

“You mean your eyes? But you recovered, didn’t you?”

“No. I didn’t. I mean from the cruelty. The bloody obscene cruelty of those fiendish little bastards of children when they had somebody helpless like me at their mercy. Pardon me.” With suddenly trembling fingers he relit his pipe, then proffered her a crumpled Sweet Caporal from a flattened package. But Jacqueline shook her head abruptly and took out of her bag a small leatherbound case in which lay tightly packed about seven yellowish-brown cigarettes; she selected one and Ethan shielded the match for her, his hands still trembling.

“Caucasian cigarettes,” she said. “A gift from a Scottish admirer—they were sent him from Constantinople by a Russian exile.” There was no one looking and she kissed him, looking long into his eyes. “But you don’t wear glasses.”

“It wasn’t that kind of trouble. It was simply corneal ulceration, and it can be cured these days in a fortnight or less.”

“My dear darling. Did you have such a wretched childhood?”

“Properly speaking I didn’t have any childhood at all, though cheerfulness, as they say, would keep breaking in. I hope you’ll admit I acquired a sense of humor at least. My father sent me away year after year to prep school—a boarding school in Stoke-Newington of which he was one of the directors and which boasted, by the way, of being Edgar Allan Poe’s alma mater. I like to think it was, even if most of the old buildings have been pulled down. But once there, divided in their mind, I daresay, as to how to treat such a valued, if useless pupil—they wouldn’t let me do any work, or play any games, so I just wandered about the grounds in dark glasses, or a double eyeshade, or one eyeshade, according to the status of my affliction, and had a perfectly wonderful time looking after the headmaster’s dog for four years or so. Meanwhile also keeping the head himself, who had a wife unsympathetic on that score, well supplied with whiskey. Well, there was no law in those days against a child going into a spirit merchants, or buying it at the chemists. His brand of usquebaugh was Golden Guinea, I recall…Altogether the ideal life.”

Ethan also recalled for her that despite these special privileges he’d been kept in a state of semistarvation, was lucky if he saw an egg or a glass of milk in a month, and that the services of one school doctor were dispensed with for having tactlessly argued that gross malnutrition was at the root of the trouble. Following this, an occasional spoonful of malt was added to his diet, apart from which he never remembered receiving any treatment for his eyes beyond zinc ointment, castor oil, and a flogging, when he had a relapse, from a junior master (who had attributed his condition, Ethan did not mention, to “certain dirty schoolboy habits…” As had his father, who however, when Ethan was home for the holidays, preferred to beat him over his chilblains with a razor strop, at the same time insisting—which Ethan didn’t mention either—how his filthy vice which had probably already led to complete impoverishment of his blood, would result in atrophy, complete idiocy and finally death at the age of nineteen.)

“As I was saying, the old man preferred the razor strop,” Ethan went on, “I told you that sort of eye trouble could be cured in a short time today. But my father didn’t condescend to take me to an eye specialist until I was thirteen…He’d lost Mother some years before all this started and of course I couldn’t guess what he was going through at the time. Finally he took me up to London and a Queen Anne Street ophthalmologist put cocaine on my eyes and simply scraped the affliction away in half an hour, like a sailor scraping rust off a deck.”

“Good God, Ethan,” Jacqueline said, “I never in my life heard such an awful story. Good God, it must have hurt you!”

At the far end of the field a three-quarter broke away from the disbanding scrum, sold two dummies, cut in over the twenty-five, dodged the opposing fullback, changed his course and sprinted at the corner flag, knocking it down as he slithered in to score a try. Not satisfied with that, the captain of his side made the rare decision of selecting the same man to attempt its conversion into a goal. Taking his aim wonderfully, still panting, covered with dirt and blood, the exhausted three-quarter did so, kicking right from the corner of the twenty-five. Curving in from its great wide angle the ball hovered, dropped accurately over the cross bar.

“But if you ask me didn’t I have any happiness at all in my youth, the answer is yes,” Ethan said. “Bravissimo!” he joined in the renewed applause. “When I was seventeen I left my public school and signed on a sailing ship for five months and went to Ceylon and I was happy when I was aloft. In fact the higher aloft I got away from everyone on board the better I liked it. My best friend of all was the moonsail, which is the highest sail of all, which almost doesn’t exist, and I became so fond of it the captain said when I left the ship I better take it home and go to bed with it or I wouldn’t be able to sleep, just as the saying is among sailors they won’t be able to sleep when they get home unless they hire someone to pour buckets of water on the roof all night. You’d have thought I’d have learned something too from that experience, which was a devilishe pastime in many ways, and you’re quite right I did, though it hadn’t occurred to me really what till this moment…I ran into the bosun in Birkenhead a year after I’d got back—he’d been quite a tyrant on board—and we had a beer together and he said to me: ‘Ethan, I wouldn’t say you were one of my star turns, but you were a good lad, and I never knew you shirk a dirty job, and now I suppose you’re telling all your tiddley friends you had enough experience to last you a lifetime after all we went through on that packet, and you went through with your old bloody bosun hazing you and one thing and the other.’ I told him I’d enjoyed a lot of it but on the bad side I thought I’d taken as much as anyone could expect to take on a first voyage, to which he replied: ‘First voyage! If you want to be a real hard case like me you’ll go back on another ship, worse than that one, with a bloody bosun ten times worse than I ever was, and that’ll be your first voyage!’ ‘You haven’t had a first voyage yet, son,’ he said.”

Jacqueline appeared to find his laughter catching, for she laughed herself till she got out of breath, and even seemed to be half crying.

“But at least you had a father,” she said finally, as the whistle blew prolongedly (the game, probably the last of the season, over, won—to judge from the catastrophic thwackings of approbation the three-quarter was receiving, that now nearly brought the fellow to his knees again—won at the last moment for his side by the last indefectible and indefeasible place-kick, and the players began to disperse toward the pavilion.

“Oh yes, had and have a father. He’s living in Niagara-on-the-Lake again, in the house where I was born, poor old chap. I’ve grown kind of fond of him, though I’m not much more popular with him now than I was then…Sure, I had a father all right all right.”

“Well I’ll tell you what,” Jacqueline said gaily. “I didn’t…That is, I did…But I’m a bastard…And now we’re going to a beer parlour.”

IN THE NIAGARA, A pub from whose suddenly opened door crashed a hubbub like a tape-recording of black brandts in the mating season, sitting in a niche in the Ladies and Escorts, under the notice forbidding alcoholic beverages to minors and Indians, Jacqueline drank her beer and said:

“You’ve been holding out on me, you’re a famous man, I saw your picture in the Sunday supplement last week.”

“Quite possibly. I got into the news for breaking up a case based on prima facie evidence a couple of years ago and they’ve been writing me up ever since.”

“You’ve known me all this time, we’re even engaged, and you never once thought there was anything odd about me, you don’t know anything about me either.”

“No. I didn’t. I don’t.”

“Maybe that’s because you’ve lived so long in England. Well, I’ll tell you—” Jacqueline laughed and took a long drink and blew out a flood of smoke from her yellow “Caucasian” cigarette. “It was very interesting. I was picked up on the doorstep as a baby. And just for the record, my father and mother were coming back from the movies…No, but what’s really funny, it was a D. W. Griffith film, Intolerance—or maybe Way Down East.”

Or perhaps (and ah, the eerie significance of cinemas in our life, Ethan thought, as if they related to the afterlife, as if we knew, after we are dead, we would be conducted to a movie house where, only half to our surprise, is playing a film named: The Ordeal of Ethan Llewelyn, with Jacqueline Llewelyn), or perhaps The Ten Commandments, he resisted a temptation to say. “Go ahead, it seems I wasn’t taking you seriously after all.”

“It was in Winnipeg, and I’m not joking. That was after I’d been abandoned by my real mother as a child about a week old.”

Ethan buried his hands on his face on the table.

“No, please don’t say ‘Good God, how awful for you,’ after all, I didn’t know anything about it. Sit up, you fool. My adopted father, that is, he’s my real father too—you’ll probably like him a lot—well—” Jacqueline laughed again in a certain oblique smoke-wreathed way, and trying to fan off the smoke, that was to become so familiar. “That isn’t quite the point either. What I want to make clear is—my life.” Like a little tree divesting itself of rain, she shook from herself a merry cascade of laughter. “My father is a magician.”

“Oh? You mean he’s an illusionist—in show business?”

“Heavens, how he’d like that—no I mean, like Werner Kraus in The Student of Prague, that we’re going to see at the film society—only a good magician, a white one.”

“I see,” Ethan looked wildly, and said blankly. “—Um, you got as far as their finding you on a doorstep. The white magician, not played by Werner Kraus—”

“Yes, though that isn’t the point at all. Anyhow they did, and not having any children of their own—my dad and mum, my father and my foster-mother that is—they took me home and in the end adopted me. And they’ve always been very good to me, and I really loved them. And still do.”

With a pang Ethan saw the lonely child lying on the cold doorstep under the moon. Assiniboine Street. The Wild Assiniboine!…The two figures, the magician, muffled in a dark cloak, and his wife, in coat of shabby karakul, emerge from the back exit, over which glows a single ruby bulb, of the Strand Cinema. Picking up the infant in swaddling clothes they move off down the dark alley under a maze of telegraph wires past the Bone Dry Fertilizer Company. The moonlight falls on their faces, revealing for a moment the pure cold face of the child, slides down the iron of fire escapes. “Fain would I, dear, find some shut plot of earth’s wide wold for thee where not one tear, one qualm, would break the calm,” Ethan thought, looking, deeply moved, though feeling a sense of complete unreality, around the roaring beer parlour: he caught sight of their waiter and held up four fingers for more beer.

“I thought you ought to know, but now I tell it it doesn’t sound interesting at all.”

It is bad enough to learn one’s home life began by being plucked up as a baby on a January night from a freezing doorstep in Winnipeg without being informed that this sort of thing in England is considered a subject for loud laughter, Ethan was thinking, both the stock-in-trade of Victorian melodrama and a household joke, together with the drunken man embracing a lamp post, father compelled to play Jack-pick-up-sticks, the hysterical wife throwing a flatiron at him, and the deserted woman, also with her chee-ild, in a snowstorm, on Waterloo Bridge. In this category British humor also placed cripples and all those suffering from the pox, and Oscar Wilde, handcuffed, compelled to stand from eleven A.M. to two P.M. at Clapham Junction before being consigned to Reading Gaol. Truly those were right who said the British could take it. It was a pity there was often such a sneering curve to the otherwise stiff upper lip.

“By the way,” Jacqueline was saying, “I mean—are you religious?”

“Religious?…I’ve seen so much suffering, heartbreak, so much, sometimes lying awake at night I want to bite trees—I want to travel the world, walk through all the thunderstorms, to put a stop to someone innocent being hurt—”

“I mean do you have any specific religion?”

Ethan shook his head slowly at the terrible beer parlour, shook his head very slowly without looking at her, much in the manner of a doctor at the wheel of the car trying, without taking his eyes off the road, to convey mutely to someone beside him that the injuries of the man in the back seat would not prove fatal. A Niagara of noise, he thought.

“My parents, when in Wales, attended the Church of England. Though my father had a Puritan streak, he had a romantic side too, once went off to Czarist Russia after a quarrel with my mother, when I was three or four. Nowadays there’s nothing he believes in. My grandmother—my father’s mother that is, actually despised my father, which wasn’t surprising since it was her husband made the cash after all, made it in the Cariboo, while it was my father lost most of it—my grandmother was a fanatical Swedenborgian—”

“Anyhow, my father’s a real live magician—how do you like that?” Jacqueline interrupted. “Many people think he’s crazy as a hoot owl. Will you give me a cigarette?”

“You’ve got one burning in the ashtray.”

Jacqueline smiled, peeling a fleck of yellow cigarette paper from her lower lip. “Father’s in Toronto now, lecturing at the Cosmological—I think the Cosmological Society Temple is what it’s called.”

More beers arrived while she told him for the first time about The McCandless. Since she laughed frequently both at her own remarks and everything Ethan said, it was hard at first, amid this Saturday tumult of the beer parlour, to obtain any sort of clear or plausible picture. But after a while a pattern emerged, and the strangest thing about this pattern was that shortly one found one had taken it for granted, like those inhabitants of Vicksburg, Pennsylvania, he had read about, who, happening to observe one sunny afternoon of the eighteen-seventies an object shaped like a man pedaling solemnly across the sky at a height of three thousand feet, more or less, questioned finally neither their eyes nor their sanity, but watched with interested attention while the forever unexplained phenomenon passed overhead in the rough direction of Maryland.