To My Parents

A 58-Year-Old Looks Back on Looking Back

Before

1962

1963

1965

1966

1969

1972

1973

IN THE FALL OF 1971, while in my freshman year at Yale University, I sent a letter to the managing editor of the New York Times, suggesting that I write an article for him. I did not know this man, and he knew nothing of me—and in the years since I have recognized the oddness of my suggestion. But at the time, writing that letter seemed like a fairly normal thing to do. Maybe I’d get a negative response, and maybe none at all. But in this respect, at least, I felt a surprising amount of ease and self-assurance. If a person wanted to write an article for the greatest newspaper in America, what better way to make that happen than to ask?

My boldness did not extend beyond the page. Until that September I had lived my whole life in a small New Hampshire town, where I had always felt more than a little like an outsider. Never a social disaster, exactly: I was secretary of my eighth grade class, and chairman of the decorations committee of my junior prom; I won the roles of Lady Macbeth and one of the aunts in Arsenic and Old Lace in Drama Club. I never viewed myself as remotely normal, though I longed to be perceived that way. I studied the actions of the popular kids—and the characters on television shows, particularly family situation comedies—to pick up tips on how I might accomplish that. While other kids in my school played sports and went on dates—made friends, attended church, learned how to ski, and later smoked pot and had sex—I spent my time writing stories on yellow legal pads and typing them on a Smith Corona portable. (To any reader born after the year 1980 or so, I will add here: that was a brand of typewriter. Now extinct.)

I was a naïve girl, and in many ways, young for my age. For me, the typewriter—and what I produced on it—provided my best connection to the world. That, and acting in plays, and listening to music. The first thing I’d bought with my babysitting money, in seventh grade, was a portable record player housed in a bright red Samsonite case. Then I joined the Columbia Record and Tape Club, to take advantage of their offer of ten albums for a penny. My inaugural purchases: Johnny Cash, At Folsom Prison. The first Joni Mitchell album. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. A comedy album called The Sex Life of the Primate. Also the Rolling Stones.

Music inspired me to think about the world, and want to change it. After I heard Pete Seeger, around age ten, I felt ready to devote my life to making the ideals of peace and harmony expressed in “We Shall Overcome” come true. I’d travelled by bus to Boston to see Joan Baez, and sat in the front row at the ice arena in our town when Janis Joplin performed there. After I got home, the first thing I did was write a story about it. There was that typewriter again—my instrument, though I might have preferred the guitar.

My parents always encouraged my writing. Nearly every night, in our family living room, I’d read my stories out loud to the two of them, and they would offer comments and suggestions. No pats on the head or suggestions to keep up the good work, however. The criticism was extreme. The standard simple: excellence.

I learned a lot in that living room. Since age fourteen I’d published my writing in magazines, chiefly Seventeen. This didn’t make me popular, or provide the sense of belonging I hungered for, but it allowed me to feel acknowledged and heard. For a small-town girl who could never have earned a place on the one team her school made available for girls—cheerleading—this was a rare and precious thing. It also allowed me to give my mother—a brilliant woman in her own right, who’d overcome the challenge of her immigrant parents’ poverty to earn a PhD from Harvard, only to find her career aspirations stifled by her role as a wife and mother in the fifties—the opportunity to shine in the reflected glory of her child’s successes. I cannot remember a time I was too young to recognize the longing to lay success at my mother’s feet and earn, for her, the recognition that had eluded her in her own young years.

It was a collection of clippings from these magazine stories of mine—a short story I’d written about a car accident that had killed four boys in my high school the year before, and an article about the Miss Teenage America pageant I’d attended (strictly as observer, not contestant)—that I’d included with my letter to the New York Times editor, as examples of my writing. He wrote back and said OK, he’d assign me a story. I was not all that surprised by this. It made sense at the time.

As for my assignment: There was only one topic about which I could have been called any kind of expert, and it was this one he asked me to explore. Myself.

“We’d like you to write about what it was like growing up in the sixties,” the Times editor told me in the letter that arrived in response to the one I’d sent to him a few weeks before. “Tell how the times you came of age shaped your idea of the world ahead of you. Write about your generation, and how you see the future.”

My generation. What did I know of how other 18-year-olds lived—the normal ones, those cool and self-assured-looking types who had their lives all figured out (or so I imagined) as I did not? I fit in about the same at college as I had in high school: not very well. At the time I didn’t have a clue how many other people my age there were—boys as well as girls, including even those very cool types I studied closely—who felt much the same as I did.

At the time, the only place where I felt truly safe and comfortable was my old bedroom back in the house where I’d grown up. So a few days after receiving my assignment from the New York Times, I made my way over to the spot in New Haven where cars got on the highway and I stuck my thumb out. Even as I was embarking on writing the article about my bold and supposedly anarchic generation, the place I chose to write it was my childhood bedroom, with my parents close by to advise.

So many things were different in those days and the prevalence of hitchhiking as a means of getting around was one. Even in 1971, however, the idea of an 18-year-old girl heading north on Route 95, by herself, on a rapidly darkening Friday afternoon, for a roughly 200-mile journey to New Hampshire, would have been viewed by most people as questionable if not outright dangerous. I was an odd girl, though—as, later, I no doubt became an odd woman. There were things that scared me—things that seemed easy and unthreatening to other girls my age—like calling up a boy to ask for a homework assignment, or getting on a chair lift, or walking into the Yale dining hall and finding a spot to set down my tray. But the idea of getting into the car of a stranger (often a man) and heading out onto the highway with him, alone, seemed not to alarm me.

It was this same odd mix of fearfulness and self-confidence, sophistication and naïveté, that no doubt explained my ability to present myself to the New York Times as a writer worthy of consideration for an assignment—and later allowed me to write about a phenomenon I termed “the embarrassment of virginity”—while remaining unable to walk into a drugstore and buy a box of tampons, or look a boy in the eye when I spoke to him. At age 18, I was afraid of many things I didn’t need to fear. And unafraid of other things that, had I been wiser, should have terrified me.

I wrote my article for the New York Times that weekend, back home in New Hampshire—read it out loud to my parents, as I always did with my work, for their suggestions and critique—and after correcting the spelling errors, delivered it, by a method not far from the typewriter in line for extinction: the US mail.

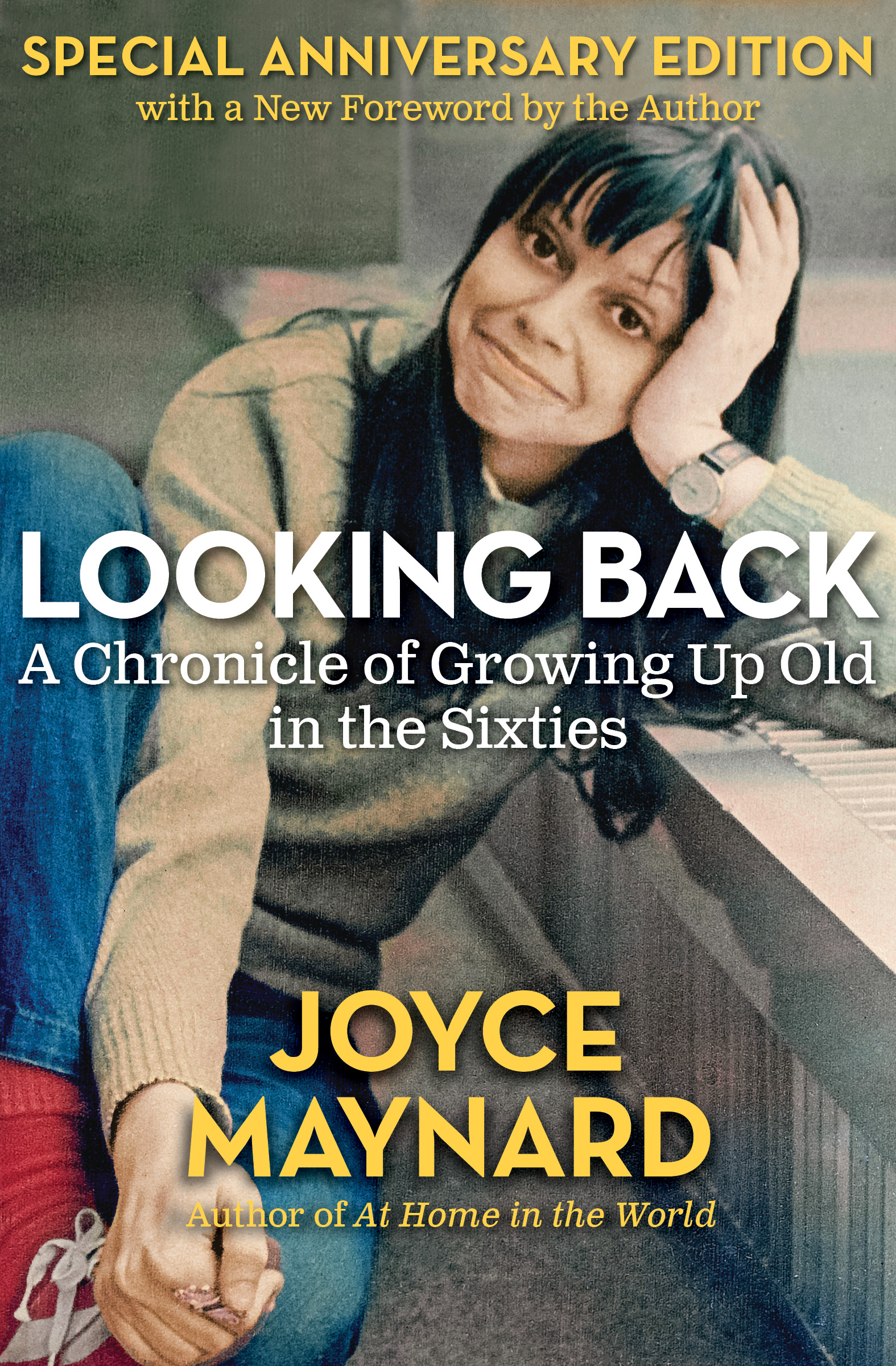

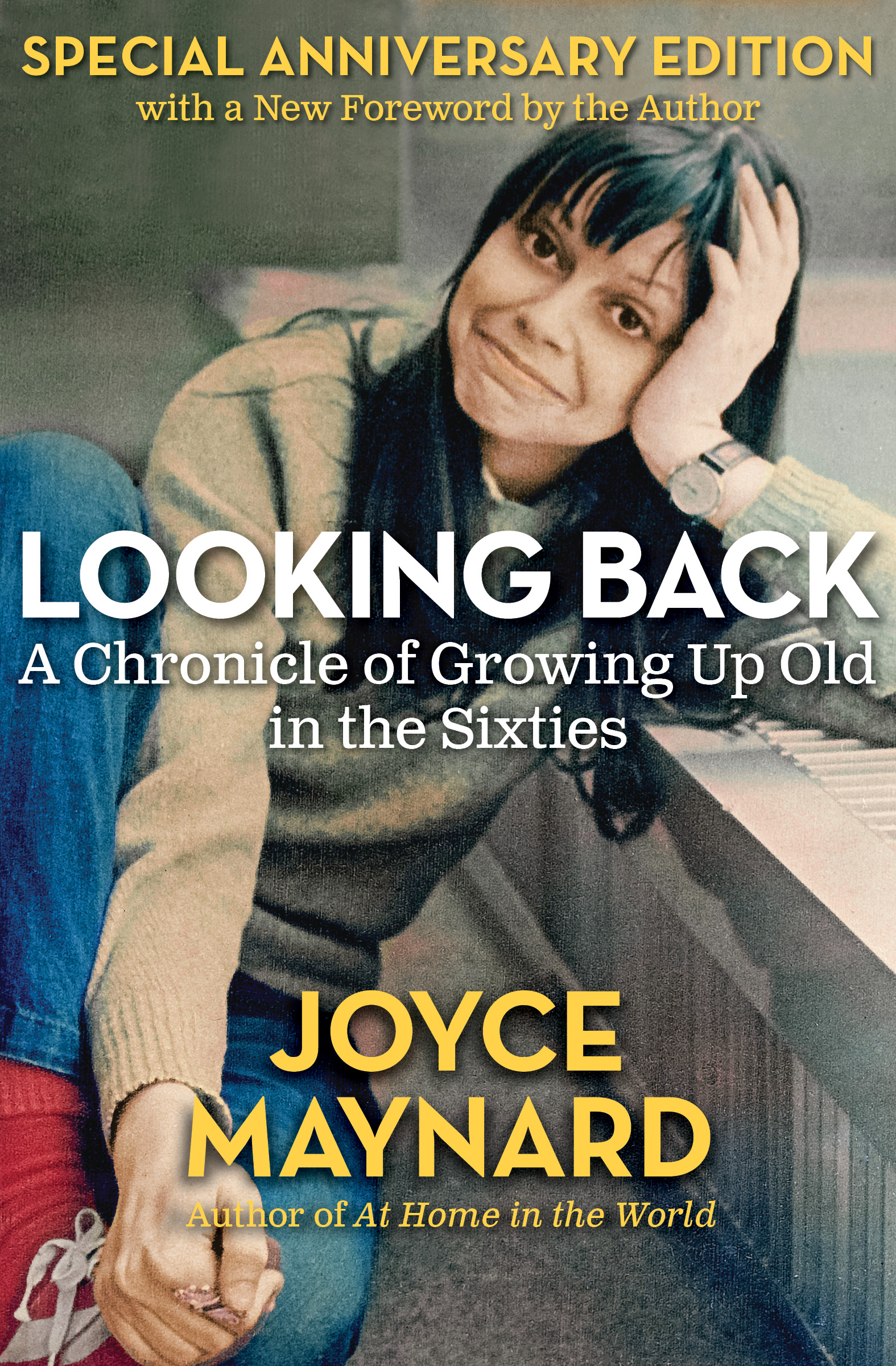

Shortly after that the call came: My article would be running in the Sunday New York Times Magazine. A photographer had been assigned to come to the Yale campus a few days later, for the purpose of photographing me.

I wore my blue jeans for that shot, and a pair of red-and-white checked sneakers, and an old grey sweater that only partially concealed how thin I was at the time: 96 pounds. I always knew the exact number, in those days, and never let it get above 100 without cutting out food altogether. (That, too, represented strange behavior, though in this way at least, I remained representative of a significant number of girls at my university, and many other places too.)

My article—bearing the headline “An 18-Year-Old Looks Back on Life” (the irony of which escaped me at the time)—was published on April 23, 1972. It’s a date I know well because in so many ways my life changed that day.

It’s impossible to convey to a reader of a subsequent generation how much impact the appearance of a single magazine article could have on a young writer’s career back then. Starting with that photograph of me in my jeans. Not beautiful, certainly—nobody could have mistaken me for a model. But there was this look on my face of amusement and hopefulness. I was a girl just starting off on her adventures and whatever my words might have suggested, with their tone of affected weariness, the openness of my expression showed someone who believed what people told her, had faith that life was good. I was not simply eager but hungry to experience the world.

These days, there are so many places to go for images and news and information, so many words and pictures competing for public consumption, it’s unlikely that any one piece of media—with the exception of a viral video, maybe—could become the focus of so much attention, all on a single day. But in 1972, far fewer outlets existed for a person’s voice, so when you made your way into one of them, as I did that day, people took notice in a big way. I acquired the label of “spokesperson for her generation.”

Within two days of the publication of that article, three enormous sacks of mail were delivered to my dormitory room. Inside were hundreds of letters—close to a thousand—from all over the country. Many were from people my age. Some had liked that article a lot, they told me; others—many—were angry about something or other I’d said in it. Many young readers took exception to my somewhat goody-goody position on drugs—I was against them—and the apparent prudishness of my comments about people my age having sex. (Those attitudes failed to conceal the deeper truth: My biggest problem with sex at the time lay in my own failure to locate a boyfriend.) Then there was the view—justifiably voiced by many—“Who do you think you are, to speak for ‘our generation’?”

Mixed in with those letters—and easily identifiable by the important-looking envelopes they arrived in—were all kinds of professional offers: magazine editors and book editors wanting to meet with me, and radio producers and television producers suggesting that I might have a career in broadcasting, and one invitation, from a casting director, to audition for a movie. As a girl who loved to act, and sought out the stage at every opportunity, this one inspired particular excitement. The movie was The Exorcist, and I did audition, though it was a girl named Linda Blair who got the role.

But on other fronts I did better: Before the week was out I had signed a contract to expand my New York Times article into a book, with the delivery date set for the following January and publication planned for exactly one year from the date of my original piece in the Times.

From deep in those same stacks of mail, one letter emerged that would have more of an impact on me than any of the others. This one, like the rest, came from a reader of my New York Times article, but from the first sentence, it was clear to me this was the voice that mattered most. I can still remember how it felt, holding that letter—typewritten, with that slightly irregular spacing that revealed the use of a manual typewriter. The onionskin paper, the elegant handwriting on the envelope: “Miss Joyce Maynard.” The postmark, Windsor, Vermont—a town just over the border, by covered bridge, from my home state of New Hampshire.

But it was the words themselves, not how they were laid out on the page, that moved me so that, reading them, I sat down on my bed and wept. I had the sense, reading this letter, that whoever had written it, though I had never met him, possessed a kind of knowledge and understanding of me that nobody on the planet—not even my parents—had ever achieved.

I felt this way even before I got to the signature, and in fact, it was never the name revealed in the signature that mattered to me. It was what his words suggested: that for the first time in my life, perhaps, I might not be, as I had tended to believe, alone on the planet—a solitary observer, clicking away on her typewriter.

There is no way to speak about the writing of Looking Back—the book you are now about to read—without saying a few things about the circumstances and the wrenching state of conflict I inhabited during the months in which it was written. Though I didn’t recognize this at the time, in many ways my struggle represented a form of conflict women have faced for generations, whenever the lure of making art or the pursuit of personal ambition flew in the face of the desire for love and family, the desire to please a man. The desire to be who the man she loves wants her to be and if she isn’t those things, to change.

In my case, the man for whom I transformed myself was the author of the letter that had showed up in the mail sack that day, whose words to me in that first letter—and all the ones that followed, and in our conversations over the next eleven months—had the effect of nullifying virtually all other voices in my ear for a very long time.

The author of this letter was J. D. Salinger: 53 years old at the time and living with his two children in my home state of New Hampshire, where he already enjoyed the reputation of a recluse who shied away from contact with the press in any form, a man who had turned his back on the whole idea of publishing his writing. Though it had been publication—and the spectacular success of his first novel, The Catcher in the Rye—that made his exit from the stage and life on that New Hampshire mountaintop possible.

The story of my relationship with Salinger is one I have recounted in another book—though it would take me another 25 years before I granted myself permission to tell it. Up until then I had adhered to Salinger’s prohibition never to speak of him and I honored that—with the belief I owed this man nothing less than my total silence about what had taken place between us—until the age of 42, when my own daughter reached the age I was when I came under the spell of his words to me and I read his letters with the eye of a mother, not a young girl any more.

For a girl whose aspiration since the age of six had been to achieve fame and fortune in New York City—a girl who learned to type at age six and received a mimeograph machine for her seventh birthday, so she could print her own newspaper—the chance to publish a book was, or would once have been, my dream come true. But in the spring of 1972, and the summer and fall that followed, I was a young girl in love—and more than that, a girl who believed that the man she loved was the possessor of all wisdom, all understanding, and that it was my role in life to do everything he said.

And so at the very point when the career as a writer that I had hungered for seemed not simply within reach, but firmly in hand, the man I worshipped told me that publishing a book was an inherently hollow and dangerous pursuit, that there was nothing good to be found at college, and that the only safe and good place for me to be was with him, in his house in New Hampshire, sealed away from everything that was wrong with the world, which was very nearly everything.

I corresponded with Jerry Salinger for the remainder of that spring at Yale. I first met him face-to-face two months after the publication of my story in the New York Times. Shortly after that—with college out of session for the summer—I took a job writing editorials for the New York Times, planning to spend the summer in a four-story brownstone just off Central Park that had been offered to me, free of charge, in exchange for my dog-walking services. The plan was that I’d write a little for the Times, write about the Democratic National Convention for Ms. Magazine, deliver an article titled “The Embarrassment of Virginity” for Mademoiselle, begin work on my book, walk the dogs, and visit Jerry on the weekends.

Within a few weeks, I’d quit my job at the Times, given up the brownstone and found other caretakers for the dogs, tossed aside a number of magazine assignments. Jerry Salinger had driven into Manhattan in his BMW for the purpose of picking me up and bringing me back with him to New Hampshire to spend the remainder of that summer. That August found me at a sewing machine store in Lebanon, New Hampshire, buying myself a Golden Touch ’N Sew.

A month or so after that I gave up my scholarship at Yale and my little off-campus apartment, abandoned my old blue Schwinn bicycle and my red record player, and moved the remainder of my possessions to Jerry’s house—believing I would live in that place, with that man, forever. That he was 35 years older than me and the father of a daughter just one year younger than I was (or that on the day I moved in, he pointed out with some disparagement that I was “acting like a teenager”) had no effect on my belief that ours was to be an unbreachable lifelong bond.

It was in his house, over the course of that fall and early winter—subsisting on a diet of mostly raw food, with a great many additional dietary restrictions, as well as other restrictions extending to the music I listened to and the clothes I wore and the people to whom I spoke, or was instructed not to speak, and above all, the ideas I embraced or rejected—that I wrote Looking Back.

I can still remember where I sat on Jerry’s velvet couch, writing this book—with a bowl of nuts on a TV tray table next to me, and his old dachshund, Joey, snoring on the rug. (Salinger himself would be in the next room, working on his own writing, though he never said precisely what it was.) Nights in that house, he’d set up a movie projector and (this being years before the advent of videos and the VCR, let alone DVDs) we watched old movies he owned in 16mm print form. The Lady Vanishes. The Thin Man. Laurel and Hardy. Other times we might tune in to reruns of The Lawrence Welk Show.

Reading over now what I wrote all those years ago, I can hear my young self speaking: that sharp, precocious, slightly know-it-all voice, so well-trained by my mother from all our hundreds of evenings in the family living room, when I read my stories out loud from my yellow legal pads. Certain parts make me smile. Some could make me weep (like my cool assessments—written as if this were no more than a fascinating cultural phenomenon—of the kind of eating disorders that were, in fact, tormenting me). I wrote about the diving under my desk for air raid practice during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Beatles’ first appearance on the Ed Sullivan show, and catching the first glimpse (via the cover of Life magazine) of what a human fetus looked like in utero. But I was not so adept at revealing my own inner self. That part of my story I kept off the page, mostly.

I had been offered the impossible assignment to write about my generation and I supposed the way to do this was to smooth over the rough edges of my life and create something of an Everywoman. (Or an Everygirl, anyway. White, middle class, and heterosexual.) I made liberal use of the third person plural in this book—spoke of “my generation” more than I spoke of myself. If there were odd and troubling—and very likely embarrassing—aspects to my experience, I kept those hidden, out of fear that to do otherwise would invoke judgment and disapproval in a reader and shame in my own self.

This is why, in the 160 pages of Looking Back, no mention can be found of the fact that I grew up in an alcoholic family—though my father’s nightly drinking was a central and formative part of my growing up and one I now understand I shared with so many of the very people at my school, and beyond, from whom I worked so hard to keep this hidden.

I spoke, in my book, about obsession with looks and body image, but only in the abstract, as if I were an anthropologist. In truth, the girl who wrote Looking Back lived in terror of gaining weight, stepped on the scale several times a day, and regularly made herself throw up (a skill taught to her by the man she loved). In a visit with the editors of a major national magazine that same year, I suggested that they assign me an article on the topic of bulimia, but was told by the editor-in-chief that this sounded way obscure and bizarre for a general audience. Ten years later, Karen Carpenter—whose voice provided the soundtrack to a thousand senior proms and weddings of the day—was dead of anorexia.

At 18, I couldn’t write about my difficult relationship with my mother, or the struggles between my sister and me, or the fact that my best friend at college had struggled with the knowledge that he was gay. I didn’t write about the social studies teacher at my high school who invited one of my best friends to move in with him during her junior year (and she did, though she never get over the habit of addressing him by the title “Mr.”). Nor did I write about the relatively common practice at my Ivy League college, in those days, for young girls (including my roommate) to get together with their graduate student teaching assistants and, on occasion, their professors—or the fact that when it happened, nobody seemed to view this as a problem. If anything, a relationship with an older person (as modeled by Mia Farrow with Frank Sinatra, and Margaret Trudeau with the Prime Minister of Canada) demonstrated a girl’s sophistication, success, and desirability.

Most strikingly absent, of course, from my 1972 account of my young life, is any mention of the first love affair I ever had, embarked upon, as an 18-year-old virgin, in the summer after the publication of that article in the New York Times. I do not say, in the book that purports to be the story of my life to date, that I have dropped out of college (never to return, though I didn’t know this yet) and moved in with a man 35 years older than I am. I do not say this man is J. D. Salinger.

Only one small clue exists in the pages of the book you are holding in your hand, suggesting what was actually going on in my private life at the time I was writing it. It appears on the second-to-last page of Looking Back, in the final chapter, that I wrote on the morning of January 1, 1973—which happened to be Jerry Salinger’s 54th birthday. I don’t say that it was his birthday, but I refer to having rung in the New Year “with popcorn and Guy Lombardo.” Talk about extinct phenomena: The only people watching the band leader Guy Lombardo on New Year’s Eve were people over 50, probably. But I was living with one of them and being the girl I was then, I listened to the music he liked and kept my Johnny Cash and Rolling Stones albums in the closet.

I kept a lot of my truest self hidden there too.

Certain parts of this book—the sense of the narrator as a perpetual outsider, sitting on the sidelines at every party she attended, watching everyone else get drunk, or stoned, or fall in love, while she herself kept scribbling on that infernal legal pad—strike me now as familiar, and touching, and sad. Sometimes the voice of the girl I was comes across as funny and wise, and sometimes terribly young. Her observations can be perceptive and compassionate—when she speaks about the power of Seventeen magazine to shape girls’ sense of themselves and their sense of who they should be, the fear of death, and the social structures of junior high.

As strongly as I did when I was 18, I can feel the humiliations described in these pages of a boy at my school (I remember him vividly still) whose voice never fully changed, so every time he spoke in class (and this happened with less and less frequency) you never knew what octave he’d be speaking in. (Years later, I heard he had committed suicide. No doubt there were other problems, and plenty of them, that accounted for this. Still I am struck—reading my description of him all those years before—by my recognition of how cruel the world can be, and was, to people who were different. And my own way of addressing that, which was to keep safely under wraps the evidence of my own greatest sources of discomfort and shame.)

There are times here where my assessments of my life, growing up in the sixties, strike me as overly grandiose and sweeping, for sure. There are also some moments in these pages when my 18-year-old self captured something that feels, all these years later, like truth—and sometimes, oddly enough, what I say shows less in the way of how much things have changed than it does how much has stayed the same. That happens when the voice of the narrator—me, at 18—writes of being “worldly not from seeing the world, but from watching it on television.” And when I speak of my television-occupied world as “a visual glut” that served to deaden the senses to the point where hardly anything seemed amazing or wonderful any more.

I can muster affection and sympathy for this girl who was me—for her yearnings for religion, her admission that sometimes she changes her outfit nine times before going out, her willingness to admit she doesn’t smoke marijuana and have sex. (Though she slips into the third person when she starts talking about this. First person is just too close to the bone.) But at other times—mostly when making pronouncements about youth and “my generation” she is maddening, to the point where I want to shake her.

“You think you know so much,” I would tell my young self. “Just wait.”

I remember a conversation I had many years later with my own daughter, when she was about the same age and came home to visit after her first semester at college. She had been taking a course called “Introduction to Feminism” taught by a famous former Berkeley radical, and she was exploding with ideas and opinions not yet fully supported by life experience. “Oh, Mama,” she said to me—weighing in on a decision I’d made that struck her as evidence of my lack of enlightenment concerning the female condition—“you have no idea what women have gone through.”

Here is some of what I did not know at 18 about what women go through, as they pass beyond their teens and into their twenties, and beyond that to the thirties, and the forties, to the age I own as I write this now: 58.

I didn’t know that my parents, the people to whom I dedicated Looking Back, and the home I’d lived in for all my growing-up years—the place I’d hitchhiked back to from New Haven for the purpose of writing my article because it had seemed to me like the one safe spot on earth—would break apart within months of finishing my book. Within twelve months my parents had divorced—with great anger and bitterness, brought on in no small part by the presence in my father’s life of a young girlfriend, only a few years older than I was.

The war in Vietnam ended around the time Looking Back was published. Nixon resigned. The soldiers came home. “The boys of 1953, my year, will be the last to go,” I’d written in my book. I didn’t know how many among that generation of young men would spend the rest of their lives struggling with what the experience of fighting in that war had done to their minds—and how through their attachment to those men, the women who loved them and the children they bore would struggle too.

I didn’t know—none of us did—that there would be something more dangerous about sex than pregnancy and that was AIDS. In 1972 the Beatles were still together. Girls at my high school had to pay 25 cents for the privilege of wearing pants to school—one day a year. Pluto was still a planet. Muhammad Ali was The Greatest. My parents were alive.

I knew I would have children and that part didn’t change. But I thought that when I got married, the marriage would last forever. I believed the words to songs, particularly the romantic ones. I believed in women’s liberation (the Equal Rights Amendment had been defeated the year before, but Billie Jean King would shortly beat Bobby Riggs). Product of an era when girls playing basketball were allowed no more than three dribbles (so as not to tax themselves, presumably) and those girls playing soccer at my school had to clear the field of stones before the game could begin (while the boys got the good field), I would have said I believed that women were entitled to any and all rights afforded men. I never for a day questioned that I would have a career. But I also eventually embarked on a marriage in which I accepted, for years, the notion that the majority of child care and housework would fall to the woman. Same as it had for my mother.

I supported Roe v. Wade and the right of a woman to choose abortion. I didn’t know yet that six years later, when I had an abortion myself, the real-life experience would feel a lot more complicated and painful than embracing the political position.

I was an old-fashioned girl who baked bread and wanted babies. (This was a nearly radical position at the time, by the way.) And like many girls (despite the powerful rise of feminism during these years, and my own intellectual support of what the feminists talked about), I was a good girl, raised to please. I derived my sense of my own worth from what the arbiters of power in my world conveyed—the editors of Seventeen and the New York Times, the admissions board at Yale, my parents. If a man I loved told me I was a wonderful girl and a real writer—as Jerry Salinger had told me when he wrote me that first letter—I felt I might be such a person. If that same man—so much wiser and more brilliant than I—told me differently, I would believe this, too.

All of that fall, while I was writing Looking Back, Jerry Salinger had expressed his displeasure in my project, even as he looked over my manuscript, suggesting changes—many of which are reflected in the final work. It was Salinger—who spent hours meditating daily and urged me to do the same—who inspired the reference in these pages to Zen meditation, though (having missed the point, perhaps) I made the suggestion that I practiced the art by watching television. It was Salinger who urged me to end my book with a reference to the birds on his bird feeder that day and the importance—in a climate of so much faddishness and fashion—of holding onto a respect for the natural world.

More important, it was Salinger who raised the question of whether my old dream of achieving fame and fortune in New York City would provide the basis for a meaningful life. Had he not written that first letter to me, and all the ones that followed—had I never met him—I can guess where I would have been headed: to a career in television, very likely, or as what he would have called “some goddamn female Truman Capote, hopping from one talk show couch to the next one,” carrying on a series of “hysterically amusing little exercises in assassination by typewriter.” Without ever asking myself the question (here came Salinger’s voice in my ear again): What purpose might all my words serve besides the shoring up of my own ego?

“Do you ever see a student any more who simply loves to write, for the pure joy of the thing?” he asked me. “Or are they all hell-bent in making a name for themselves?”

“Someday, Joyce,” he had said to me, “you’ll give up this business of delivering what everybody tells you to do. You’ll stop looking over your shoulder to make sure you’re keeping everybody happy. One day a long time from now you’ll cease to care anymore who you please or what anybody has to say about you. That’s when you’ll finally produce the work you’re capable of.”

Back then, what mattered to me most was still to please the person I loved best. This mattered more than being a writer, or simply being myself. I would be whoever I needed to be, if it allowed me to hold onto the love of the man I believed to be funnier and more interesting and wiser and more enlightened than any other.

When, in January, a small item appeared in Time magazine, disclosing that I had dropped out of Yale and moved in with the author of The Catcher in the Rye, Jerry Salinger exploded at me with so much fury I hid in the closet until I fell asleep there and emerged begging forgiveness.

In the spring of 1973, three weeks before the much-publicized release of Looking Back