THE

HARDMEN

THE VELOMINATI are founders of a singular online community – www.velominati.com – which celebrates the history of road cycling with a distinctive point of view, best described as (ir)reverence. Their infamous Rules challenge cycling fans to emulate their heroes in everything from training (‘it never gets easier, you just go faster’) and equipment (‘the correct number of bikes to own is n+1’) to sock length and coffee choice. The Rules were published in book form in 2013. Frank Strack, Editor in Chief, spreads the word at bike shows worldwide, and in his column for Cycling magazine.

ALSO BY THE VELOMINATI

The Rules

THE

HARDMEN

LEGENDS OF THE CYCLING GODS

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PURSUIT BOOKS, an imprint of

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Frank Strack, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 236 2

Contents

Foreword by David Millar

Prologue

A Note on Style

PART I // LES ROULEURS

1. EDDY MERCKX, PART I // The Improbable Hour

2. NICOLE COOKE // Birth of a Hardwoman

3. SEAN YATES // Always Full Gas

4. MARIANNE VOS // 2012 Olympic Road Race

5. EDDY MERCKX, PART II // Belgium, April 1971

6. REBECCA TWIGG // Mind Over Matter

7. JACKY DURAND // Go Long Or Go Home

8. ANNIE LONDONDERRY // Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better

9. BERNARD HINAULT // The Badger versus The Dog: Paris–Roubaix 1981

10. MEGAN FISHER // Overcoming

11. FRANCESCO MOSER // Passista

12. RIK VERBRUGGHE // Stage 15, Tour de France 2001

13. BERYL ‘BB’ BURTON // British Twelve-Hour Time Trial 1967

PART II // LES GRIMPEURS

14. LUCIEN VAN IMPE // The Spotted Flandrian

15. STEPHEN ROCHE // La Plagne, July 1987

16. MARCO PANTANI // Les Deux Alpes

17. ANDY HAMPSTEN // The Gavia, 1988

18. NAIRO QUINTANA // Rule #9 Grimpeur

19. RICHARD VIRENQUE // Cracked Actor

20. TYLER HAMILTON // The Accidental COTHO

PART III // DE KLASSIEKERS

21. ROGER DE VLAEMINCK // Mr Paris–Roubaix

22. LIZZIE DEIGNAN // A Lady for the Sport

23. GILBERT DUCLOS-LASSALLE // Never Say Die

24. JAN RAAS // The Dutch Make Hardmen Too

25. EDWIG VAN HOOYDONCK // ‘Eddy Bosberg’

26. SEAN KELLY, PART I // Guns

27. MAPEI // Destroying Cobbles, Selling Glue, Forging Rules

28. ANDREI TCHMIL // Paris–Roubaix 1994

29. PETER VAN PETEGEM // April 2001

PART IV // LES DOMESTIQUES

30. TONY MARTIN // ‘Panzerwagen’

31. MATHEW HAYMAN // Paris–Roubaix 2016: Journey(Man) to Hell

32. JENS VOIGT // Conan’s Great Battle

33. ADAM HANSEN // Batman

34. EROS POLI // Mont Ventoux, Tour de France 1994

PART V // I VELOCISTI

35. FREDDY MAERTENS // Champagne in the Bidon

36. DJAMOLIDINE ABDOUJAPAROV // The Champ on the Champs

37. SEAN KELLY, PART II // More Than Just a Pair of Legs

38. ROBBIE MCEWEN // July 2007

Finale

Glossary

The Rules

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Hardman Biographies

FOREWORD

It’s weird, you were so soft when you started, I remember thinking that. I thought you gave up too easy. Yet for some reason you’ve become harder than almost all of us, that’s not normally what happens.

Christian Vande Velde to me, sometime in 2011

He was right of course, I didn’t come into cycling to repeatedly bang my head against the proverbial wall, I came to win bike races in the same way my heroes Miguel Indurain and Maurizio Fondriest did. I didn’t plan on all the hurting that would come with the 1,100 times I didn’t win, not even mentioning the stuff that damaged me off the bike. I might have rethought it all if I had. Probably not, though. I still love it, you see, even with all the damage. And in truth I was like a moth to a flame when I discovered professional road racing; my fate was sealed there and then. It seemed so completely and utterly bonkers. I had no idea just how bonkers until I joined their ranks.

The rules were everywhere. The whole sport was dictated by them, they existed in the ethereal; well, they had to be since nobody ever bloody wrote them down. Each one of us had to learn them through the school of hard knocks; if you didn’t learn, you didn’t last. Yet, if you did, you graduated beyond the neo-pro stigma and became un homme du métier – which might translate into English as ‘skilled in the art’.

I was a pretty good artist. That was even how the French would refer to me; ‘L’Artiste’ (well, Cyrille Guimard would, though not in a positive way – more like a gentle put-down). To be fair, it was better than being Le Dandy, which they also called me. That was probably the time in my life Christian VdV was referring to when he said I was soft. He was right; a grain of sand could stop my machine (I actually read a directeur sportif say that about me in L’Equipe, which, by the way, didn’t help our relationship).

The point of this is that I ended up cracking because of that softness, and making mistakes; doping, cheating, lying. All because of softness and a wrong love. I didn’t stand up for my own values; I went too deep into a dark part of the métier, one that had always existed and was never really talked about; the one of doping. I went deep. I lost everything. Then I came back and fell in love with the sport all over again. I didn’t care about their rules anymore, I only adhered to mine. In the process I became a harder and much better bike racer and, dare I say, person.

That’s the point of this book; it’s about the bike racers who made up their own rules. Because, as much as each of us must learn the rules from others at the beginning, it is only when we make them our own that we become hard.

David Millar

PROLOGUE

The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.

T. E. Lawrence, in Lawrence of Arabia

It is said that after his non-stop run from Marathon to Athens, Pheidippides immediately collapsed and died. Perhaps the most comprehensive example of athletic suffering imaginable; it also demonstrates the only sensible thing to do after running such a distance. This is the only mention we will make of running in this text. We are Cyclists, not savages.

The Velominati are dedicated to maintaining the cannon of Cycling’s culture and etiquette in the form of The Rules. Cycling is a sport with a rich and colourful history; its traditions and codes of conduct have evolved over more than a century. The Rules (listed in full on p. 207) cover all aspects of this, ranging from states of mind (Rule #9 // If you are out training in bad weather, it means you are a badass. Period) to traditions (Rule #13 // If you draw race number 13, turn it upside down). And from aesthetics (Rule #14 // Shorts should be black, and Rule #33 // Shave your guns) to etiquette (Rule #43 // Don’t be a jackass, but if you absolutely must be a jackass, be a funny jackass).

Chief among them is Rule #5:

Rule #5 // Harden the Fuck Up.

Rule #5, also known as The Five, or The V, is the essence of what it means to be a Cyclist: to persist in the face of intense suffering. It is a state of mind, bordering on a lifestyle. It means you are tough and disciplined, never following the path of least resistance. It doesn’t mean you can’t also fuss about with aesthetics or complain about the weather. But after you’ve finished faffing about with aesthetics and ancillary details you still submit to the deluge and go out and do your training.

Strength and pain are both transient things; they wax and wane not just with the rhythm of our training but with the cycle of our morale. Certainly the hours we pour into our sport play a crucial role in our fitness, but our minds play perhaps the biggest part. The mind is what dissociates pain and effort from the task at hand; it is the mind that silences the pleas coming from the body to yield. This is the essence of The Five.

Nearly every religion pays close heed to the concept – and the value – of suffering. The Buddhist approach is particularly helpful in its emphasis on experiencing things without clinging to them. Everything changes; embrace change and the fluidity of life. There is a beautiful freedom when you dissociate from the suffering; there is liberty in the realisation that how you endure suffering is a choice. This element of choice, what psychologists refer to as the Locus of Control, is part of what allows Cyclists to feel pleasure through suffering. (Either that or it’s a personality disorder.) If we are to believe the white-bearded master computer program in The Matrix,1 having a choice – even an illusory one – unlocks our sense of control and opens up an avenue of personal discovery by which we might learn something fundamental about ourselves or achieve some kind of salvation. Like Michelangelo wielding his hammer to chip away fragments of stone that obscure a great sculpture, we turn our pedals to chip away at our form, eventually revealing our true selves as a manifestation of hard work, determination and dedication.

As Cyclists, we choose to suffer; suffering liberates us from our daily lives. It presents itself in many forms: the pain of a climb, the cold of a rainy winter training ride, the unbridled fury at a clicking bottom bracket or insubordinate drivetrain. Life is a complicated mess of interdependencies in which we are more likely to be passengers than drivers; politicians, corporations, friends, family, morals, laws and physics routinely get in the way of us achieving our dreams. To ride our bikes and suffer by our own choice is to take control, if only for a short while, and escape into a more simple world.

But it goes beyond a state of mind and control over our uncontrollable lives. Suffering is also about taking care of ourselves mentally so we may each be a more complete person.

One evening, an elderly Cherokee brave told his grandson about a battle that goes on inside people.

He said, ‘My boy, the battle is between the two wolves inside us all. One is evil. It is anger, envy, jealousy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.

The other is good. It is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion and faith.’

The boy thought about this for a minute, then asked his grandfather, ‘Which wolf wins?’

The old Cherokee simply replied, ‘The one that you feed.’

Cherokee legend

We already ride for many reasons: the sense of freedom, the harmony, the feeling of flight as we hang, suspended, just a metre or so above the ground. There is the feeling of strength in our muscles as we force the tempo and near our threshold.

The demands of our lives mean that we can’t always ride as much as we want or need to, and when we don’t ride, our mental states start to deteriorate. Under these circumstances there is an enormous therapeutic value to climbing on a bike and going into the red, if only to remind ourselves that we can make ourselves hurt simply because we want to. We restore our confidence that we can do whatever needs to be done in life.

Other times an unexplained and unsolicited foul mood occurs, and it needs an exorcism. The best therapy in these situations is to make an appointment with The Man with the Hammer.2 Just going for a ride doesn’t flush the system; we need to run the motor on fumes for a bit in order to force a reboot. The policy is to keep turning on to a road that leads farther from home until the lights go out; only then are we permitted to ride home.

That ride through total exhaustion is where the magic happens; the sensation of hopelessness at the daunting road ahead slowly melts into certainty that we can override the messages coming from the body and keep tapping away at the task at hand. Eventually a heavy kind of dull strength returns to our muscles as the body finally decides to collaborate in the mission our Will has set it. By the time we get home, drained, we are reborn. We don’t always need to ride in order to be a complete person, but generally we are better people when we find the time to turn the legs around and feed the Good Wolf.

Bicycle racing was born of a simple idea: to test the limits of human endurance. The first official race was held on 31 May 1868 at the Parc de Saint-Cloud in Paris, along a 1.2 kilometre course. Racing distances quickly grew: first to 20 km, then 50, 100, 200. In single-day events the ultimate test of endurance was reached with the 1,200 km Paris–Brest–Paris, which continues to this day as an amateur randonnée event, for which entry is restricted to people who have absolutely no appreciation for how far 1,200 km actually is.3

The first Tour de France, held in 1903, featured a route of 2,428 km in six stages: an average of 405 km per stage. By comparison, the twenty-one stages of the 2015 Tour’s 3,360 km averaged only 160 km each. The bicycles in 1903 were leaden beasts with two gears on a flip-flop hub, meaning: get to the base of a climb, get off, loosen the wheel, turn it around, fix it in the ‘low’ gear. Get to the top, reverse the process. More cumbersome than the modern drivetrain, certainly, but the idea is still the same: go as fast as you can at the start, and as fast as you can at the finish. As for the middle: go as fast as you can.

They say a Cyclist is measured not by skill in riding a bicycle, but by their ability to suffer. The ones we revere the most are the ones who endure suffering especially well. We refer to them as the Hardmen. The Hardmen are the riders who relish a good fight and never give up. Quite simply, they are willing to venture deeper into the Pain Cave than anyone else is.

Not all Hardmen are the same. In this book we group them by the five traditional classifications of rider: rouleurs, grimpeurs, klassiekers, domestiques and velocisti. Rouleurs are all-rounders, possessed of a smooth, powerful style on the bike. They generate enormous speed for absurdly long periods of time, can climb well enough to be dangerous on the shorter ascents and go downhill as if they have no imagination whatsoever.

The grimpeurs are climbing specialists. Possibly the most mysterious of the Hardmen, these are tiny, waif-like riders who prosper due to a startling power:weight ratio and an enormous capacity for intense suffering in the high mountains, where gravity and thin air join forces to make the pain unbearable for mortals.

Klassiekers specialise in the one-day classic races held during the spring and autumn and often have a particularly unhinged penchant for the Cobbled Classics of early spring. These are big, tough riders who can produce the sort of sustained power that carries them at high speed over the brutal stone roads of northern France and Belgium, to emerge from the other side looking like grinning bog monsters.

The domestiques are team workers who labour in the wind day in and day out, in the service of their team leader. They perform all manner of thankless chores, from distributing food and drink from the team car, to setting the pace at the front of the bunch, to loaning out their bicycle or wheel if their leader has a mechanical problem.

Finally, the velocisti are the quick-fuse, short-twitch, fast riders in the bunch: the sprinters. They can bump shoulders and touch wheels at 60 kph, then unleash a ferocious turn of speed as the finish line approaches. This is a rare capacity, and makes for a particularly specialised type of rider: should the road point uphill, you will find these creatures wallowing at the back, cursing a blue streak at all the skinny little bastards who are leaving them in their dust.

All five types of rider can be judged by their results, certainly, but also – our favoured method – by their panache, heroism and humanity. The truly iconic riders became so through stories of their deeds.

The Keepers fell in love with Cycling during the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s and beyond, and have become ever more obsessed with its history and legends.4 Thus, our frame of reference leans towards the riders who inspired us during that time and the myths about them that we discovered as we dug ever deeper into the sport. Also, we’re more interested in riding our bikes than we are in doing things like ‘research’, so this book is written in true Velominati style: (ir)reverently and subjectively. We imagine that if it feels true, it probably is true. And if it happens to be wrong, then maybe being wrong makes it right.

When we convened our Hardmen Selection Jury, we quickly came to the realisation that we had many more subjects than we had room for, and we knew we couldn’t spend the rest of our lives sitting in the Velominati bunker arguing, pint in hand, about which riders should be included. So we went with our favourite stories. And we certainly didn’t worry about who was or wasn’t allegedly doping.

These are the riders and rides that inspired us, and we hope they inspire you. We are the Velominati, and these are the Hardmen.

Footnotes

1 Science-fiction film starring the dubious Keanu Reeves, in which computers take over the world and enslave the human population, while keeping them asleep and letting them think they are living out their lives in 1999. Which, contrary to the Prince song, was not one giant party.

2 He stalks all Cyclists. He cannot be outridden or avoided. Everyone meets him eventually, and everyone remembers him. Ride long enough and hard enough and there he will be: hammer cocked – boom! – out go the lights. You are now riding in slow motion, children are running easily alongside, laughing and mocking. Congratulations, you have just met The Man with the Hammer.

3 Randonnées are events in which Cyclists are generally expected to be responsible for their own care and feeding, in the original style and spirit of early bicycle racing.

4 The Keepers of the Cog; the five principal authors of Velominati.

A NOTE ON STYLE

To reflect our reverence for Cycling heritage, we have chosen to name the five principal parts of this book in the language of the European peloton, which is to say usually French but occasionally Dutch or Italian, depending on which country is most fanatical about the type of rider in question. Hence rouleur, domestique and grimpeur are French, klassieker is Dutch (Flemish) and velocista Italian. Using the language of the peloton might come across as Europhile snobbery, but our intention is to express our respect for the culture of our sport. And possibly be a bit snobbish.

We also maintain a stylistic orthographical irregularity, capitalising the first letter of certain words in order to emphasise their significance within our vernacular. This includes Cycling, Monument, Pro and (of course) Hardman and any other word referring to something or someone we are quite certain has earned it.

Finally, we would like to emphasise that while we have endeavoured never to stray too far from the truth, we also hate to let facts get in the way of a good story. Witnesses, after all, nearly always destroy a fantastic tale.

PART I

LES ROULEURS

The frame lies forgotten in a dark corner of the workshop; it has been perhaps twenty years since it was last ridden. Hand-built of lugged steel tubing, it is a thing of beauty. Crafted by an artisan, it probably represented little more than a tool to its owner: a tool for inflicting suffering on himself and on those who dared follow his wheel. The paintwork tells a tale of countless hours of work by man and machine, their bond forged through their suffering. The paint on the top tube is pocked where it has absorbed the sweat that used to pour from the rider.

The owner of this frame could spend all day churning immense power through the pedals – on the front of the bunch or attacking, solo, with nothing but his shadow and the wind for company. This frame belonged to a rouleur. A rouleur is an all-rounder who rides well on most types of terrain. Rarely the best at any one discipline, but annoyingly strong, irrespective of the parcours.1 Their secret power is the ability to dish out massive amounts of what we call The V for an unbearable length of time.2 Usually wearing an expression of maniacal satisfaction.

Rouleurs and domestiques occupy some of the same space in Cycling: they can bring big power for hours on end and take pride in making others suffer.3 The difference is that a domestique lacks the killer instinct of a rouleur. A rouleur is not only a strong rider but also a leader and a winner. Rouleurs lead from the front, they lead by example; they suffer with the rest of their team, and when the team is done, they go out for another helping of pain.

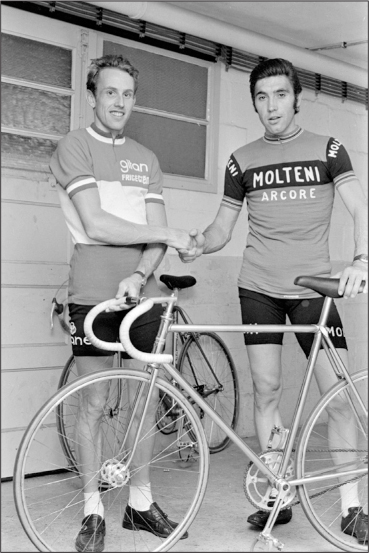

Joop Zoetemelk (l) concedes the race to Eddy Merckx (r) pre-start on account of his schoolboy loafers.

Eddy Merckx, The Prophet, the greatest Cyclist of all time (and Elvis’s doppelgänger), was the consummate rouleur. Team training sessions would always set out from his home in Brussels, departing en masse, to submit to the work that was required. Merckx would lead the rides, choosing the route on a whim, forcing the pace as he pleased. If anyone was dropped, it was their duty to find their own way home and, before the assembled team, explain precisely why they had humiliated themselves thus. That’ll learn you.

A rouleur also generally exhibits the sporting quality we refer to as being the Perfect Amount of Dumb. That is to say, they are smart enough to do what is required to find peak fitness, disciplined enough to train in all kinds of weather and can manage a race tactically while hypoxic from effort. Yet they never question the wisdom of suffering so much for something so transient as riding their bicycle; they are just dumb enough that making it stop never occurs to them.

Rouleurs are some of the hardest of the hard riders. They are defined less by their size than by their style on the machine; a Magnificent Stroke tuned to sustained power, not to high revolutions or bursts of acceleration.4 Rouleurs tend to be good time trialists and do well on short climbs, but when the race profile starts to look like the cardiogram of a teenage boy who just saw his first pair of boobs, they are usually to be found in the laughing group.5

Due to their wide power band, rouleurs are the riders who tend to study the race map, looking for the right terrain with the right kind of lumps if they’re going to have a chance of being at the front. They are also possibly the most exciting to watch race; races of attrition suit them, as does bad weather – and when they’re in the break, they’re usually just dumb enough to take their strength for granted and overestimate themselves. Betting on the rouleur might be a gamble, but their style of racing often means that, even when they lose, it was a great show.

Footnotes

1 Not the relatively new sport wherein people jump around an urban landscape like uncaged monkeys but instead a classic Cycling term referring to the profile of a race route. Why don’t we just say ‘profile’? Because ‘parcours’ is French and it is customary to adopt the old European terms for such things whenever possible in order to further mystify our sport to those not familiar with it. Compare use of ‘terroir’ in wine-speak.

2 Shorthand for the Velominati’s all-important Rule #5: ‘Harden the Fuck Up’. The power of The V, or The Five, surrounds us, penetrates us and holds us together. Not unlike The Force, in fact, though it won’t help you aim your photon torpedoes.

3 Domestiques are teammates who ride in service of their leader and thus rarely win races themselves. See Part IV.

4 A rider’s smooth, powerful stroke. Pedal stroke.

5 Also known as the gruppetto: a group of riders joined together in bleak solidarity at the back of the race.

1

EDDY MERCKX, PART I

The Improbable Hour

The Hour Record is distinct from other Cycling events by being raced over a defined time, rather than distance. In a normal bicycle race the objective is to cover the prescribed route in the least possible amount of time. There is a not inconsiderable psychological benefit to this, and in fact it can drive us to push harder, especially when climbing. Upon sight of the crest of the hill we can tick down the gears and push harder just to make the suffering stop that much sooner.

The Hour Record is immune to such tactics. Suffer as much as you can, for an hour. No more, no less. Sixty minutes. And then count the laps to see how far you went. And that’s not even the best part. We’re not talking here about an undulating course where you gain speed on a descent, to carry over the next rise and ease the strain in the legs even if for a brief moment. We are talking about an hour on a velodrome’s uncompromising track. The black line on the track represents a virtually flat oval along which the distance of the lap is measured. The rider must adhere as closely as possible to this line or sacrifice unmeasured distance; round and round for an hour, with a lap typically consumed in less than thirty seconds – quite a lot less if you are harbouring any hopes of breaking the record. Based on the size of the velodrome and your target distance, challenging the record means around 120 laps or more, anticlockwise; hopefully you are better at turning left than Derek Zoolander.

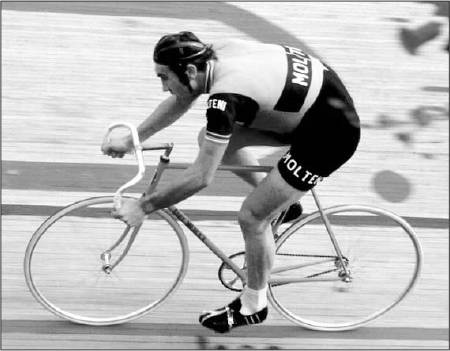

And so it was writ: none shall look better suffering than The Prophet.

Before their hour attempt, the rider will have determined how far they think they are capable of going, and will have scienced the shit out of things like average lap split times and even a specific lap-by-lap schedule they want to keep to, in order to have even a hope of meeting their goal. The other painful element here is that the rider is on a track bike, not a typical road bike; the gear is fixed, so there is no changing to an easier one when you realise you’re fucked. The choice is final, and you won’t know how good or bad your choice was until you are committed, much like that time your cousin double-dog-dared you to jump the water pipe on your skateboard.

For a hundie-odd laps, fighting dizziness and boredom are the least of your worries. Your biggest worries centre on the fact that, with every turn of the pedals, you are breaking down the fibres of your muscles one by one, leaving less functional muscle mass available for the next revolution of the pedals. Assuming one hundred revolutions per minute mostly because it makes the arithmetic simple and everyone hates complicated arithmetic, that’s 60,000 revolutions of the pedals where your muscles are physically less capable of sustaining the required power than they could the revolution before. But still you have to maintain and sustain the effort; pacing is crucial.

There is a horrible joke about a young and old steer standing on a hilltop, looking down on a bunch of cows grazing in the valley below. The young steer says to the old, ‘Let’s run down there and fuck one of those cows!’ The old steer says, ‘What say we walk down there and fuck all of ’em.’ The Hour is all about being the old steer.

Eddy Merckx was the Greatest Cyclist of All Time. Full Stop. Before Merckx set fixed wheel to track, the Hour Record had been broken twenty-three times, and by the most prestigious names in the sport. Fausto Coppi and Jacques Anquetil both held it; each was regarded as the greatest rouleur of his generation. But the man who first held and popularised the Hour Record was Henri Desgrange, who went on to found and organise the Tour de France. Henri was obsessed with figuring out ways to make Cyclists suffer more, to find better ways to make riding bicycles a test of human capability. And a long string of Cyclists submitted to this test, in search of an unbeatable Hour Record. At the time of Eddy’s 1972 attempt that record had been set by the Dane Ole Ritter in 1968, with a distance of 48.653 km.

Setting an Hour Record necessitates going out with guns blazing but also being as consistent as possible in your lap times, due to the aforementioned malicious muscle-fibre-breakdown effect. Eddy, however, had other plans. There are minor records for the fastest 10 and 20 km efforts, which are unrelated to The Hour, but which he felt compelled to take on along the way, due to his insatiable appetite for winning things. This meant starting his effort like the young steer, but finishing like the old.

Merckx utilised every aerodynamic advantage available to him, including a special silk one-piece skinsuit and a custom frame built by Ernesto Colnago. He had his drivetrain and handlebars drilled out to remove all unnecessary material in an effort to make the bike as light as possible. His handlebar stem was the first ever made of titanium, a material poorly understood at the time; inspection of the stem reveals it was cut from a solid billet of metal and filed by hand to give the shape of a traditional stem. The file marks remain visible.

Merckx, of course, set a new Hour Record of 49.43 km, but the effort meant he had to be carried from his bicycle. After he had composed himself, he said:

Throughout this hour, the longest of my career, I never knew a moment of weakness, but the effort needed was never easy. It’s not possible to compare the Hour with a time trial on the road. Here it’s not possible to ease up, to change gears or the rhythm. The Hour Record demands a total effort, permanent and intense, one that’s not possible to compare to any other. I will never try it again.

He later said the effort took a year off his career; I’m only glad it was from the tail end and not the front end or middle bit.

A full eight years later it took one Francesco Moser with an ultra-high-tech aerodynamic bike to break Merckx’s record. Moser’s record stood until the 1990s, when Chris Boardman and Graeme Obree traded the record, using ever-evolving time trial positions. The technology was advancing more quickly than the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) had a stomach for, so it issued new regulations that prohibited all but the most basic bicycle design.1 Going a step further (back), in 1997 they modified the Hour regulations to stipulate that all future attempts be made on a ‘Merckx-style’ bicycle: round tubes, spoked wheels and drop handlebars. All prior records set using aerodynamic equipment were reclassified as ‘Best Human Effort’ distances, and Merckx’s 49.43 km mark was re-established as the official Hour Record.

The first rider to attempt this new (old) Merckx-style record was Chris Boardman, who broke it by a whopping 10 metres. Boardman was the consummate bicycle geek, going so far as to work with Royce, a small component manufacturer based in England, not only to build him a near-frictionless set of hubs and bottom bracket but also to develop special spoke nipples that were recessed into the rims. Boardman was delighted with this innovation and convinced of the aerodynamic gain it would bring. (Years later he took the bike to a wind tunnel where, ironically, it was determined that his aero nipples provided virtually no measurable advantage, apart from the obvious mental one.)

In 2015 the UCI finally came to its senses and updated the regulations to allow the kind of aero machinery universally used in time trials; this set off a flurry of attempts which culminated with Bradley Wiggins’s monster distance of 54.5 km at the Lea Valley velodrome, track-cycling home of the London Olympics in 2012.2

Footnotes

1 The Union Cycliste Internationale is Cycling’s governing body. Sometimes referred to as the Union Cycliste Irrationale, it’s the sort of bureaucratic organisation that hinders more than it governs. It turned a blind eye to the rampant doping that took place in Cycling during the 1990s and 2000s but felt compelled to limit the innovation that was taking place in bicycle technology.

2 It is worth remembering that Chris Boardman’s Best Human Effort was nearly 56.4 km in 1996, so Wiggo still technically got punked.