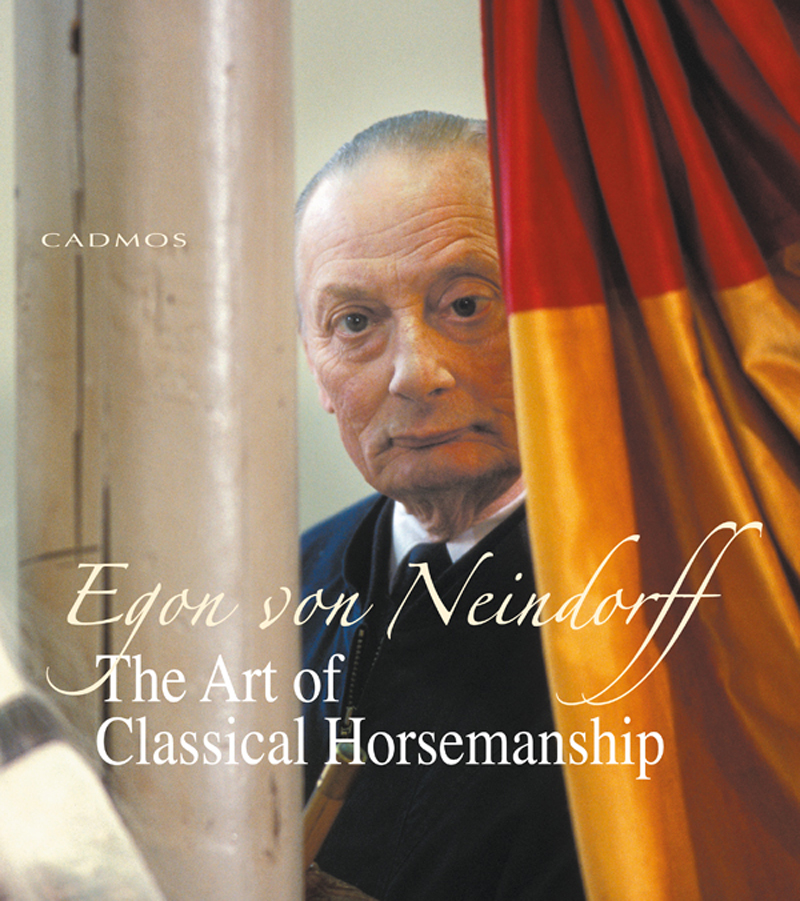

Egon von Neindorff

The Art of Classical Horsemanship

Thank you

A special thank – you to Mrs Ingrid Oehlert for editing the original text without her help, this book would have not come into existence. My thanks also go to Melissa Simms, the heiress of the name of the riding institute. She took care of selecting the photographs and opened the Egon von Neindorff archives.

A thank – you also to Prof. Dr. Ulrich Schnitzer for opening his photo archive, as well as to Mrs Karin Schweiger for looking after the final manuscript so enthusiastically.

A special thank – you goes to Mrs Renate Blank who created the illustrations.

A note from the publisher:

The photographs were selected because of their relevant content, not so much for their quality. The publishers are aware that perfection can only be a mere goal. For this reason, many private photographs have been published in this book, which have an important historical value.

Copyright of the German edition © 2005/2007 by Cadmos Verlag GmbH, Schwarzenbek, Germany

Copyright of the English edition © 2009 by Cadmos Books, Great Britain

Design of print edition: Ravenstein + Partner, Verden

Setting of print edition: Grafikdesign Weber, Bremen

Cover photo: Arndt Bronckhorst

Illustrations: Renate Blank

Picture editor: Melissa Simms

Translation: Melissa Simms

Copy-editors: Christopher Long, Linda Robinson

E-Book Conversion: Satzweiss.com Print Web Software GmbH

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-3-86127-919-8

eISBN 978-0-85788-672-9

www.cadmos.co.uk

Preface

Introduction by Gerd Heuschmann

Biography Egon von Neindorff: A servant to the pure teachings of classical horsemanship

1. The purpose of education

The foundation

Allow enough time!

With feeling and self-control

“... and they move regardless!”

Observe, feel and compare

Gradually increasing the demands to the high school level

Always searching while remaining flexible

2. Riding that uses without misusing the horse

Leveling off: or a downward decline?

Purity of the gaits

3. A riding horse matures only with time

Modern learning problems

Finding the correct measure: a serious must

The more genuine the love

From the first time we mount

About natural grace

4. A good seat can be learned

Balance and harmony

About the seat

A model and practice

5. The orchestra of the rider’s aids

Seat, feel, collection: balance in movement

Exercises to develop a good seat as a basis

Permeability... (willing compliance and the uninhibited energy flowing through the horse)

To the piaffe with merely a halter

Forehand elevation from hindquarter flexion – balance in the levade

6. The back directs

Regulator and moderator

From impulsion to the halt

An urgent task

7. From the foal to the young saddle horse

From trust to understanding

The cavesson is not aluxury

Gymnastic pre-school

Preparation and moderation

The seat used for a young horse

From loosening to the first collection

8. Work on the lunge line: versatile and irreplaceable

From nursery to elementary school

The first schooling plan

Collection can only develop through suppleness

With correctly adjusted side reins

Early stages with an assistant

9. On the way to becoming a saddle horse

There is no pattern

Driving without overdriving

Experienced and felt

The first triumph

To the passive hand

10. The prospective saddle horse

Everything smooth, graceful yet with impulsion

True obedience to the leg

Cadence: the unerring witness

Auxiliary aids, but not coercion

No restraint without driving

11. Balanced means supple

Sitting “in” the horse: the rider’s passport

Impulsion and self-carriage

Forward and straight

Logical development without conflict

12. Furthering and forming

Preferably three years “too long”

The order of errors

Suppleness and relaxation from horse and rider

The indispensable school horse

Practicing but within reason

The seat – independent from the reins

13. Correct corners with the young horse

14. The walk – the most difficult gait

Self-control and correction

A friendly filter: the rider’s hands

15. The trot – the most important gait

Resounding words and clear facts

The forward driving seat and posting trot

About rhythm and tempo

16. The gallop or canter – the third gait

The jump as an extended canter stride

On one hooftrack

The hand that is always ready and willing to yield

Drive, half-halt and be light again

Frequent canter transitions on curved lines

The canter’s influence on the trot

17. Not a secret science: about straightness, position and flexion

The first schooling “in hand”

The correction forward, even when flexed

Straightness as a basis

An equal measure – not excess

Flexions at the halt

Impulsion and inner tranquility

18. Never sideward without remaining forward

19. The shoulder-in and its preparation

Begin minimally sideward

Always more foreward than sideward

20. Renvers, travers and half-pass

From the basis to its refinement

The essential prerequisites

21. Characterized by forward impulsion: turning on the spot and moving backwards

Receiving signals

About the harmony of the aids

Schooling the entire horse

Never backwards without forwards

22. Forward when moving backward

Prerequisite: permeability – the unimpeded flow of energy through the horse

No advancement without preparation

The correction forward

For the masters only: “taking drastic measures”

23. Only for experts and connoisseurs: the double bridle is a finely honed instrument

About elementary dressage

The double bridle must fit

The rider’s hands must be ready for the double bridle

24. The naturally oriented school canter

The spring elastic yet maintaining tension

The flying change of lead

The key figure, the piaffe

The aids – not just temporary help

25. Free from constraint

26. The goal and foundation: the uphill piaff under saddle

Where the spectator turns away in disgust

Pushed, held and elevated?

Without resistance but concentrated

The rewards of patience

Self-controlled energy

27. Cadenced Stepps with great energy

On the safe side

The powerhouse: the hindquarters

The schooling path

28. From the airs above the ground to lessons in the classical art of riding

Preparation and development

Aids, mistakes and corrections

29. With driving lines and leading reins

With the friendly hand

About the schooling in hand

How does one begin?

30. The schooling “in hand”: established, refined, improved

Sensitivity without restlessness

Everything forward – even when not moving forward

The genuine test

About Melissa Simms

Preface

Horsemanship that truly deserves to be referred to as “classical,” as understood and defined by our ancient spiritual philosophers and culture, is when art and nature merge into a single living entity.

All creatures, whether man or animal, require education and time for their development. However, patience and humbleness hardly belong in today’s society, that adulates egotism and profit; nevertheless, this is still not an excuse to disregard nature as our master teacher.

However, every riding discipline necessitates the attainment of a secure foundation in order for the schooling to further develop. The theoretical material represented in our riding manuals consists of the rules that guard and guide our future.

Regardless of their international successes, the responsible individuals of our various committees, as well as instructors and all

riders, should ask themselves again whether the approved and guarded regulations are sensible and consistently written to comply with our goal, or if the goal is just the desire to win. Similarly, the modern day “baroque rider” must ask himself if he is still a

servant of classical horsemanship, or just the actor and performer for his highly talented mount.

And particularly the most successful members of our equestrian community, wherever they appear, should remain conscious of the great responsibility they have and represent themselves as role models beyond reproach.

As a man who has become old, who has spent his entire life in the company of horses, whether on the ground or on their backs, and who has embraced the equestrian art as a never-ending topic of study, I have sworn it to be my duty until the end of my life to interpret and protect the pure teachings of classical horsemanship. This for the well-being of the horse and for the pleasure of riders everywhere!

April, 2004

Introduction by Gerd Heuschmann

It is a great honor to be allowed to write a few thoughts about such a wonderful book.

Egon von Neindorff was truly one of the last great classical educators of our age. He grew up in a world immersed in the traditions of classical horsemanship and nature – oriented horse – friendly training. He later experienced many competitive successs and remained a teacher of classical horsemanship’s traditions and principles up until the day he died. Although plagued by health issues during his last years, he never ceased caring for his “works of art” which were the horses and his pupils.

Thanks to the support of a few untiring people who continually stood by his side, he was able to finish this manuscript shortly before his death. This extraordinary book is about the essence and philosophy of a rider’s life and I cannot think of any other more comprehensive work that is appearing at exactly the right juncture in our current equestrian situation.

In the last twenty years a more critical eye has been directed at the dressage sport and riding that is developing into a craft. Furthermore, there is increasing discontent among many experts as to the interpretation of our classical schooling principles.

Egon von Neindorff was a huge personality who untiringly carried the flag for the last half of the twentieth century in the battle for horse-friendly schooling and the art of classical riding. Sadly, he did not get to see the turn that our equestrian world is now taking, but without a doubt he laid the groundwork and was greatly responsible for the horse-friendly atmosphere that is developing and gaining a foothold today.

The “Pure Teachings of Classical Horsemanship” is a work that will guide the rider in search of the only correct path, provide direction and perhaps assist in the rebirth of the almost forgotten art of riding.

Therefore, for the preservation of this ideal and the pleasure of horse and rider, I wish this book the greatest possible success.

Gerd Heuschmann

Egon von Neindorff: A servant to the pure teachings of classical horsemanship

A man who devoted his life to the pure teachings of classical horsemanship; an oracle enlightening his followers about the classical riding tradition that for him was the only path he could ever walk. A man who created an inspirational setting in which he worked untiringly to further the equestrian art, a man who was never at a loss for the correct thought or pertinent word: this was Egon von Neindorff.

Egon von Neindorff was born in Dobeln-Saxon, Germany on November 1, 1923, the second son to the later General Egon von Neindorff, who was a passionate and enthusiastic rider. For young Egon, horses were naturally a way of life. He could remember being led around on them; the color of their coats, form of their necks as well as the shape of their heads. These were very special and formative moments. For example, a mare named “Karin” was one of the horses that he still spoke of even when he was 80 years old: “A soft brown and very beautiful horse, as my father’s horses often were.” Even as a very young boy, Egon von Neindorff‘s only thoughts and dreams were about horses, whether as toys or in the cavalry stable, and if he would disappear, his parents always knew where he could be found.

“Therefore, it was a natural occurrence that I asked specifically for permission to ride when I was nine years old. Of course, my father as the commander in charge was not to know that I had already been indulging in my passion, albeit rather secretly with the help of the stable grooms and my mother, and by the time he heard of my request I was already to some extent sitting passably. After approximately two years I was allowed to ride my father’s horses. These horses were temperamental and not always easy. My education began on the lunge line, which never became boring to me. At this time my father owned two horses: Libelle [Dragonfly] was a dark brown mare who was a well-schooled dressage and teaching horse. The second horse was Orpheus, which I called Seppel. He was not as well trained as Libelle, but possessed an enormous jumping talent, and as a young boy I happily obtained the permission to ride him over large obstacles.

Naturally, as a young child I was allowed to accompany my father into the stable when he was visiting the horses, and observed his offerings of a lump of sugar or other treat, thereby experiencing the close contact of these partnership-friendships. Through observation and first-hand experience I was able to become thoroughly acquainted with and understand the horse. Because I grew up in a world with horses within a military context, I became accustomed to the strict rules and regulations concerning the respect for their everyday care, surely similar to the children of breeding farm directors or veterinarians. There was only one direction to take, and I learned very early which behaviors were acceptable and which were not – while as a child I saw or heard how someone else would be reprimanded or praised.”

Egon von Neindorff grew up amidst classical horsemanship and its accompanying traditions. In the surroundings in which he lived, the military offered the only direction which he never doubted; there were no other choices. In his own personal estimation, his father was a good rider, although not “a high school dressage rider.” After being stationed in Dobeln and Leipzig, his father was transferred in the mid-1930s for four years to the city of Altenburg, where the family had accommodation near the Duke of Altenburg’s royal stables. There, young Egon von Neindorff was introduced to classical riding and stable master Kunze, who was to place his indelible stamp on the boy:

“Mr Kunze, was at this time thirty-six years old, someone who I already considered older and he was a rather exceptional man. He was stable master for the Duke Ernst von Sachsen-Altenberg and had traveled extensively. He was extraordinary in his field and schooled horses that would later be sent to competitions in Berlin’s ‘Green Week’ (a festival involving farming techniques, animals and innovative processes occurring in the industry.) When we lived there I went to school, but would often escape during the midday break and run to the stables, as I knew where to find the key. I was always around the stalls or the riding hall and would watch the riders and listen to Mr Kunze’s riding lessons. After a time I became his go-getter ‘Eggon… go get me the long whip…’ I did not hear this sentence just once. With his unconventional accent it seemed to me that he was saying ‘Eggon’ when he was giving his orders. In this vein, he once said to me, as an important person of rank and office was riding: ‘Eggon, this is a dumb person.’ I knew that I was not allowed to ask why, and would have to somehow try to decipher the message myself. Nonetheless, the experience assisted me greatly later in my life when I also became an instructor.”

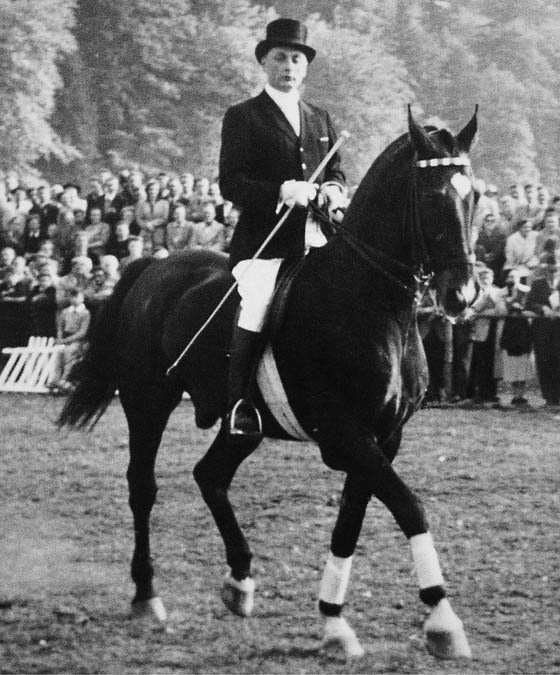

Egon’s first large tournament was in 1938 in Chemnitz, when the fifteen-year-old boy won the fourth level dressage examination on Dragonfly. The judges were involved in a discussion as to whether it was appropriate to allow the “little squirt” to triumph over the other older riders in uniform, who were already accustomed to winning. His expected triumphal homecoming was somewhat dampened by parents who, although having heard of his victory, were waiting at home and already in bed. After briefly acknowledging his achievement, the laurels were laid to rest, as there were still horses to care for, and in the von Neindorff house, healthy, correctly cared for horses were far more important than any blue ribbon.

First Lieutenant Heinz Pollay, who had been the Olympic winner in dressage in 1936, was in Chemnitz on that day performing a Kur program with his well-known horse Kronos. After observing the young boy’s triumph he approached him and gesturing to Kronos said, “If you would like to try the tall brown one in the piaffe ‘in hand’, he will show you how it should be done!” Needless to say it was a glorious moment for young Egon von Neindorff.

The young boy was always more interested in dressage schooling than in stadium or cross-country jumping. “The number of lessons and their intricacies are much more scintillating. A jump can be either high or wide. For me, the contact and complexity of dressage was much more fascinating.” Furthermore, you should not forget that horse breeding techniques at that time had produced much heavier animals that were not nearly as agile as those today.

The “pure teachings” of classical horsemanship and Egon von Neindorff were virtually cradle companions. He expresses it this way: “If a person has learned to do something then he was clearly educated, or when he makes an educated and polished impression, then he has been taught. However, I grew up in an atmosphere where there were no other directions available. As a child I was neither educated nor taught, as my path simply did not allow for the possibility of choices or the discussion of another direction. Then came the military service years when I was required to put on a uniform and was sent to the state riding schools where I was promoted correspondingly. Eventually I arrived in Elmshorn for a driving and carriage education that I completed, receiving my instructor’s certification. One could say that from birth, there has never been a single day in my life that I have experienced without a horse by my side. This remained the case during the war, when I was in the cavalry, and so my entire life has been a permanent arrangement, compromise and partnership with the horse.”

Thus, a clear direction had been established regarding his total equestrian development. Older officers repeatedly noticed his enthusiasm, and he was entrusted with responsibilities that normally would have been the tasks of more experienced riders. It was not just by chance that Egon von Neindorff became the youngest cavalry instructor during the war.

As the Second World War came to an end in Germany, he managed to leave Halle, with his two dressage horses hitched to wagons packed with his belongings, and made his way to Bad Kosen, where his mother was still living. Egon’s father had fallen at the battle of Tarnopol, in Russia in 1944. Times were difficult and in order to survive he made use of his only commodities, which were the two horses and wagons employed as both a courier service and a hearse. Somewhere, a distant rumor came to his attention that people were beginning to ride again in the west, and perhaps realizing that Eastern Germany, that had once been his home, was never going to be the same again, he made the decision to pack his wagons and harness his horses for the journey. After many unsuccessful attempts to cross the border he finally had a little luck, and found temporary employment giving the officers riding instruction at the British military border crossing in northern Hanover. However he was warned by the stable master who had befriended him that the chances were very good that his horses could be stolen or taken from him. And so, he packed once more and left in the night to continue south to the next occupied zone, which happened to be American. There, he was befriended by an American, Major Steffi, about whom he later often spoke with respect and affection. This officer, having been familiar with the name von Neindorff, and that General von Neindorff had fallen at Tarnapol, issued him with papers and a uniform so that his journey could continue uninterrupted. Egon von Neindorff’s goal was to reach the French zone, which was a vaguely familiar area to him. During the war he had been stationed in Freiburg, as a riding instructor for police officers. Eventually von Neindorff arrived in Lorrach, which was governed by the French military, on the border between Germany and Switzerland. Finally he had found a place to remain where his horses were safe and where he could establish friends and settle down. In Germany’s post-war period, most people were in need and it was normal that they helped each other. He received food ration cards from the French, and an anonymous friend put five dollars underneath his pillow so that he could exist! In 1946 , Egon von Neindorff opened his Lorrach “Riding and Driving School.” Initially, the French officers who were stationed there greeted him rather distantly, but because of his straightforward manner and organizational talent, as well as his character, honesty, motivation and empathy for people and animals, he managed to impress the village people of Lorrach as well as the French occupying force.

It wasn’t too long before he was approached by the French commander: “Neindorff, we are having a celebration and you have horses. Why don’t you put my people on your horses and show us how it is done!” Suddenly they were receiving equestrian instruction! Once, a very distinguished French Colonel said to him, “Monsieur, if somebody sees me…!” However amongst the men who rode together, there existed a comradely atmosphere of absolute whole-hearted enthusiasm.

And so as one thing leads to another, these initial relationships paved the path for the next idea to develop, which was a jumping and dressage tournament. On the appointed day the Swiss rode in pairs over the border with eighteen horses. The competition was a success and one of their riders had even won the jumping event and had his picture taken for the newspaper. But at the end of the day, the border control noticed that they were returning with only seventeen horses. When addressing the rider as to the whereabouts of the missing horse, amongst many ohs and ahs, it became clear that the horse had remained behind and the mystery was explained! This was an extraordinary gift for von Neindorff. In all aspects it was an event that was a huge success. Finally in post-war Germany, an international equestrian competition had been successfully organized! And so, again all eyes were turned to Egon von Neindorff.

“After the war, everyone was engaged in the reconstruction of the equestrian world, particularly Dr Gustav Rau in Warendorf, who was responsible for rebuilding the entire German riding system and was also responsible for the foundation of the Badische Tournament Ring of which I was a member of the founding executive board. At that time, instead of receiving prize money, the winning contestants received their transportation expenses. With this tournament ring we were able to reach many small places where competitions could take place. We also oversaw driving examinations. I would arrive with a group of fifteen to twenty riders and as a result met people here, there and all over. I had been loaned a large truck with a trailer hitch in which I could place my jumping obstacles and poles inside. I would arrive a few days before the competition and construct the obstacle course so that the competitors could practice. Afterward, the tournament would take place. In this fashion, my own competition stable developed. I personally did not compete in my own tournaments but always performed, giving a dressage demonstration.”

The classical art of riding that Egon von Neindorff had always represented was characterized in these years by three components: the horse in the campaign school, competition riding, and the crowning moment, the high school dressage. “At this time, trained horses had a separate examination and the high school level was of course the most difficult. No one would have dared to consider competing in these upper levels without possessing adequate knowledge and expertise.” The instructors at that time were paid by the German state. The only question ever asked was: “Can you do it or can’t you?” “Even in a mounted cavalry unit there were only a handful of men that were considered to have adequate expertise to be responsible for the schooling of the young horses.”

However, it was Gustav Rau who recognized in this young man a gifted talent, combined with dedication to a task and responsibility concerning the horse. He suggested to him: “We need a school.” But for Dr Rau, the equestrian sport was the most important component because he believed it was only in this realm that the necessary financial resources could be obtained that would enable the regeneration of traditional values. Dr Rau’s opinion was not shared by von Neindorff, who believed that single-minded obsession with equestrian competition would only lead to estrangement from the honest and truthful principles of classical horsemanship. “In our tournaments, a general apathy has found its way in the door, that overlooks or must overlook many things in order to obtain massive amounts of participating horse and rider combinations.”

Despite his youth, there were many reasons that compelled Egon von Neindorff to continue undeterred in his beliefs. His heart spoke to him and he knew that he could only be interested in the preservation of the art of horsemanship and a riding culture bound by traditions. His vocation had always been clear: “There wasn’t any choice to make about which profession – the profession was always there. During the war I never left my horses.”

He was of the conviction that achieving his goal would only be possible with his own special oasis where he could exist undisturbed. While at a competition in Mannheim, his older equestrian mentors, who included Felix Burkner and Otto Loerke, persuaded him to look at a supposedly lovely riding arena from the very early 1900s with additional stables and grounds in the northwestern outskirts of Karlsruhe, Germany, which had also served as a base for the German cavalry during the war. Egon von Neindorff took a train to Karlsruhe and knew immediately that this impressive hall, with its arched windows and fine architectural joists was where he wanted to ride his horses. This decisive move to Karlsruhe made it possible for him to finally and symbolically dedicate his life to riding culture without having to be influenced by anything that moved outside its gates. Thanks to the help of good friends, in 1949 he resettled with baggage to the new stable where he could be day and night with his beloved horses. Naturally, there was much to be done. Although the riding hall had escaped destruction in the war, the other buildings and surrounding grounds were in poor condition. And so, the Egon von Neindorff Riding and Competition Stable was founded at the address, number 16 Heart Street.

On the way to a competition: in previous times the horses were ridden to tournaments, because there were very few horse trailers.

Together with Orion, the massive commander’s horse who, according to Erich Glahn writing in 1953, could “without any trouble at all, move under the expertise of Egon von Neindorff, with the lightness and gracefulness of a dancer,” there was Rex, an elegant Hanoverian gelding whose specialty was beautiful flying lead changes. They were among the top horses in the early l950s who competed at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle). “The dressage competition was won by Orion and Egon von Neindorff, who both experienced the highlight of their careers. Finally, we are seeing again a half pass and extended trot ridden the way it should be.” At competitions, Egon von Neindorff’s horses were noticed as being particularly beautiful because of their apparent impulsion and hindquarter thrust, their relaxation, suppleness and honest collection while being supported by a rider who sat “into the horse” with invisible aids, animating it to achieve the best possible performance. At this time, the horses and riders were transported to competitions by train. If the train was late, or there wasn’t sufficient time to warm-up, von Neindorrf would complete a small jump or two and then ride into the test. His experienced students were also allowed to compete on his horses up to the more advanced levels. In the German dressage championships, where all of the scores for the year are combined, he was always in the first three places. He became well known because despite his youth, he was winning over older, more famous riders. In fact, he was often asked when arriving at the competition: “When does your father arrive?” No one really believed that this young man could be capable of these successes. Even Vienna’s former head instructor Herold, who would be formally introduced to Mr von Neindorff many years later in a competition at St Galen, referred to him as “the one whose name I cannot remember; I only know that he has understood the classical art of horsemanship and lives in Karlsruhe.” And so, Egon von Neindorff honed his skills in the competition arena by observing his co-riders, always attempting to further improve himself. The same horses that competed in tournaments on weekends were used during the week by Neindorff’s students for their riding lessons – true to his motto “For the student, only the best school horse is good enough.”

Egon von Neindorff’s riding hall in Karlsruhe, Germany. He moved there in 1949. Beginning in 1954 the Festival Performances of Classical Horsemanship began, and were conducted twice yearly until his death in 2004.

(Photos: Egon von Neindorff archive)

“At a tournament in Aix-la-Chapelle I was suddenly introduced to all the instructors of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna as well as Colonel Podhajsky. Afterwards, I had many thoughts and impressions: What did the other people think? I found it an amazing situation that I could have been accepted while still being such a young person. I must have attained enough recognition that Mr Podhajsky felt compelled to introduce me to his trainers. Because I was in a riding inspection unit during the war I was often sent to Vienna, and now when I arrived there I was always greeted hospitably. Naturally, as one thing led to another, my wish had always been to ride at the Spanish Riding School.”

Egon von Neindorff was an avid driver: during the 1950s and 1960s, examinations for riding and driving were held at the Riding Institute.

(Photo: Egon von Neindorff archive)

Egon von Neindorff understood that he could not serve two masters simultaneously. There was no question that horsemanship and the protection and preservation of the equestrian art and its traditions were the most important issues. So in 1954 he made the decision to cease competing, and his tournament stable made its final transformation into the Egon von Neindorff Riding Institute. He then devoted himself purely to the service of classical horsemanship and to being a custodian of the riding tradition, but not as a reformer. For him there was only one method, one path that was appropriate for all horses – though not always for all the people. Anyone who was seriously interested in learning about riding culture and who wanted to study classical horsemanship was welcome in his Institute. In 1954 the Society to Promote the Higher Equestrian Art was founded, and among its initial board members were the elite of the classical riding culture, including General a.d. Paul Lettow, Carl Berger, Riding Master a.d. Erich Glahn, Alois Podhajsky, the director of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Richard Watjen and Carl Jobst, the latter of whom also was the moderator for the first Festival of Classical Horsemanship in Karlsruhe. Together, Egon von Neindorff and others, including Felix Burkner and Otto Loerke, would discuss the future of the equestrian world in conversations that continued deep into the night. They all agreed that the Institute in Karlsruhe should become a ground-breaking educational center that would represent the ideals and traditions of the previous cavalry schools. “In their eyes, I was just the man to do this.”

Egon von Neindorff’s father had at one time attempted to have his son accepted into the Spanish Riding School, but was refused because at that time a German citizen was not allowed to receive instruction in Vienna. Therefore, von Neindorff later went to Bremen to receive lessons from the renowned Ludwig Zeiner, who had at one time been engaged at the Spanish Riding School. Mr Zeiner, who was later often a guest in Karlsruhe, was a genius with schooling “in hand,” as well as a talented inventor and painter. But initially after leaving Lorrach, in order to refine his equestrian art Egon von Neindorff traveled to Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Bavaria, to visit Riding Master Richard Watjen. Mr Watjen, who had been educated for many years in Vienna as well, was an aesthete in the handling of horses. His Riding Master Ludwig Zeiner complained that von Neindorff’s hands were much too heavy, although every report previously written about him had stressed that he “possessed a fine and sensitive hand.” Zeiner replied that this was all nonsense: “You are much too heavy with your hands!” The other opinions were perhaps correct when only referring to pleasure riding, competitions or schooling a young horse, but for the classical high school he was, according to Zeiner, “glaringly just not good enough.” Later in his own riding lessons, von Neindorff spoke often about the rider’s hands: “The hand receives but never works backward!” And then “the driving aids must always dominate over the restraining aids!”

When Egon von Neindorff was four years old he had been given a picture of white Lipizzaner stallions that was placed over his bed. It had always been his dream as a young boy to someday ride and own one himself. And so, in 1961 a Lipizzaner stallion was purchased and brought to Karlsruhe, although the first levade was performed by a Berber mare and the second by a Hanoverian mare purchased at auction. Increasingly, von Neindorff’s students assisted in projecting his reputation in competition and riding circles over the entire world. Over time, instructors, riders, judges and equestrian enthusiasts from many countries were to visit Karlruhe and Egon von Neindorff. For many years, he conducted riding seminars for the state of Baden Wurttemberg in his Institute, and in America it became possible to apply for a stipend from the Asmus Foundation to ride in Karlsruhe. He organized and gave seminars in England, Belgian, and Italy, as well as with the Royal Mounted Police in Canada, who later on a trip to Karlsruhe showed their appreciation by presenting him with two bronze globes to adorn the tops of the pillars in his riding hall.

Preparations for the classical performances were conducted alongside the daily riding lessons. Here we see Egon von Neindorff between the stable and the riding hall.

(Photo: Egon von Neindorff archive)

Over the years, the number of horses grew as well as the number of students. Egon von Neindorff searched for horses of various breeds for his school, but they had to match in color and size as well as be attractive. He traveled to Sweden, Chechoslovakia, Austria, Denmark, Holland, Portugal, Spain and France. For Egon von Neindorff, the study of the horse was a topic that he never tired of. The Institute’s horses could not cost large sums of money, but his professional eye could determine the innate talent of a young and undeveloped three-year-old that later, through its gymnastic schooling, would become a suitable school horse. All of the horses developed a solid foundation and each horse was given the necessary time since the hours were never counted, whether schooling his own horses or those belonging to someone else. From early on, von Neindorff established a connection with Portugal and became friends with a very well known breeder, Fernando d’Andrade, from whom he purchased his first four Lusitanos. One of the brown stallions later could perform a beautiful ballotade and the other a levade. However, the star of the show was to be an inconspicuous gray stallion named Jaguar, who, while not possessing the most pliant of dispositions, later was adored by spectators and riders for his breathtaking passage, piaffe and transitions into the extended trot. Jaguar was von Neindorff’s last Kur horse, and was peacefully laid to rest in 1984 on a sunny autumn day in Karlsruhe underneath the large trees behind the stable.

Egon von Neindorff continued to school his own horses and corrected them from the saddle or “in hand,” which was his particular specialty. He fully understood as well in the riding lessons how to further encourage the student’s ability and the horse’s gymnastic schooling. In 1955 the first Festival of Classical Horsemanship took place in Karlsruhe. These celebrations continued twice yearly, usually in May and October, when the Institute presented the results of its diligent and serious schooling for horse and rider to the interested public. The performances presented horses at different stages and levels of their education. The highlights included work on the long reins, work “in hand,” the Kur, airs above the ground as well as the school quadrille. From the beginning, the festival evenings were always sold out. Furthermore, it was mandatory that the performances would represent the art of classical horsemanship, and not the rider’s individual ego. As he so jokingly referred to his horses, they were now engaged as his professors and colleagues.

Egon von Neindorff was proud that during his lifetime he had resisted the temptation to run his Riding Institute in a purely business-like fashion, although the path was certainly thorny:

“My school served the ideal of classical horsemanship and was protected through my own inspiration and dedication.” “I have never searched for financial success and as a result escaped the purely business intellect with its disadvantages and advantages but have also not had to endure endless conversations with people who knew less than I did. Both would have harmed my determination. I could not be deterred from my direction because I was alone. My conviction for my vocation and devotion to the horse was so strong that nothing else could interfere with my path. The possibility that I might become ill never entered my thoughts. I was like an armored car with not too much petrol, without guns but with the agile ability to steer well and keep the wagon on the street. In a situation like this, you do not waste too many moments dwelling on difficulties but only look at the successes; though it didn’t include a private life or money-making endeavors, it did require genuine love and unwavering dedication.”

The question arises, which equestrian assets did Egon von Neindorff possess that others did not? His answer:

“The clear guidance and good fortune to be able to entirely devote myself to a singular ideal and the ability to humbly serve an equestrian tradition. I was able to remain true to myself and the love of the horse and could support my theory with knowledge, feeling and the realization of the seriousness of my venture. Remember, we believe that head and torso belong together and as a child my belief in classical horsemanship was similarly established. I was ready to receive what I was being taught and I hadn’t any doubts about whether the information was correct. I had an intuitive sense of it. The horse’s behavior confirmed my judgments; it has always been and still is the rider’s authorization as to the authenticity of his actions.

“In this manner, the student learns to respect the horse’s opinions while modifying his influences correspondingly, according to the horse’s demeanor. The pupil who has had the opportunity to have many school masters can later assess the individual horse and use the experience to expand his education which through extensive acquired knowledge takes on new nuances and complexity.

Egon von Neindorff and the Lipizzaner stallion Neapolitano, the first Lipizzaner to arrive at the Riding Institute, and the fulfilment of a lifelong dream.

(Photo: Erich Bauer)

“There will be several formative and concise moments that cannot be overlooked in the horse’s elementary schooling so that one can understand the wisdom of the teachings and make sense of it. For example, if not enough attention has been paid to the horse’s foundation then these elementary schooling faults will appear again later. Knowledge must presuppose the practice. Nevertheless, this is only possible when the rider possesses enough experience. The word ‘experience’ must encompass the rider’s aids as well. I can only guide a horse correctly when my seat transmits to my brain a feeling about what my horse is saying and allows for my immediate response with the appropriate aids. The rider must speak skillfully and intelligently to the horse. If the telephone wires are broken the conversation is ended. Furthermore, he must know which language is needed in order to communicate.”

The horses were Egon von Neindorff’s professors, his teachers and friends, whom he enjoyed referring to as “my children here in the stable.”

(Photo: E. Richter Assmann)

Egon von Neindorff sometimes explained the reasons for his Institute’s immediate success as a combination of many different circumstances. It was not only the well-schooled horses or the performances: “After the war, there definitely was chaos. Therefore, the previous cavalry officers, equestrian regiment commanders and riders, as well as breeders and veterinarians, all found a meeting point in Karlsruhe that was based on equestrian philosophy, motivated by a tradition they had all previously known and loved.” The war had required that Egon von Neindorff master many tasks involving his organizational talent. His energy, ability to grasp a situation and innate genius brought him recognition and “I grew into my position; in the process I developed many friendships. Perhaps it was because instead of hearing vacant words and pompous actions, my supporters and critics could observe the actual results of the horse’s correct education which further assisted in winning new advocates.”

The famous emblem representing the Egon von Neindorff Riding Institute was conceived at the end of the 1960s and adorns the entrance of the building today.

After the end of the Second World War, Egon von Neindorff made the long journey to Lorrach, Germany and founded his first riding school in 1946, which he called the Egon von Neindorff Riding and Driving school.

He was never unhappy that he had given up competition riding: “I was not the best salesman to represent myself, but I must add that I really never had to be. If this would have been necessary it would have altered my behavior and vision for the future.” The reality that he could not sell himself very well was well known, and perhaps the reason that many others stood by him and were available when he needed help.

For over fifty years Egon von Neindorff followed his dream, to uphold and preserve the principles and traditions of the equestrian art and to teach them to those who would come after him. He was always ready with the short but pertinent saying. He possessed the quality of a great actor in his own theater and knew how to present the classical art of horsemanship to his public, while they allowed themselves to be willingly shackled and led into his world of words, quotes from poets and philosophers, beautiful music and correctly schooled horses. Egon von Neindorff was a magician who could cast a spell with his equestrian artistry that would enthrall his spectators, and he was able to create exceptional horses that were proud and remarkable.

Christine Drangel and Ingrid Oehlert.

(Photo: Egon von Neindorff archive)

(Photo: Egon von Neindorff archive)

Riding Master Egon von Neindorff was a once-in-a-lifetime, unique personality, who unexpectedly passed away on May 19, 2004. He was a role model for friends and students. For him, discipline was not arbitrary, but rather a virtue, determined by his noble and honorable heart, which guided him thorough all his ventures and decisions. Serving people and horses was his chosen path, while remaining true to an ideal his entire life. He is buried in Karlsruhe, Germany.

Melissa Simms