This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9780753546925

Version 1.0

Virgin Books, an imprint of Ebury Publishing,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Virgin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Cicely Berry 1973

Cicely Berry has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This edition first published by Virgin Books Ltd in 2000

First published by Virgin Publishing Ltd in 1989

First published in Great Britain by Harrap Ltd in 1973

www.eburypublishing.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780245520211

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Foreword by Peter Brook

Introduction

1 Vocal Development

2 Relaxation and Breathing

3 Muscularity and Word

4 The Whole Voice

5 Speaking Poetry

6 Listening

7 Using the Voice

Summary of Exercises

Illustrations

Photographs

Acknowledgments

Copyright

Exercises are very much in fashion in the theatre: in fact, for some groups they have become a way of life. Yet we have a healthy instinct that rebels against the thought of exercises: in some parts of the world, people still sing for the joy of singing, dance for the joy of dancing, doing neither physical nor vocal training, while their muscles and vocal cords unerringly perform whatever is expected of them. Are exercises then really necessary? Would it not be enough to trust nature and act by instinct?

Cicely Berry has based her work on the conviction that while all is present in nature our natural instincts have been crippled from birth by many processes – by the conditioning, in fact, of a warped society. So an actor needs precise exercise and clear understanding to liberate his hidden possibilities and to learn the hard task of being true to ‘the instinct of the moment’.

As her book points out with remarkable persuasiveness ‘technique’ as such is a myth, for there is no such thing as a correct voice. There is no right way – there are only a million wrong ways, which are wrong because they deny what would otherwise be affirmed. Wrong uses of the voice are those that constipate feeling, constrict activity, blunt expression, level out idiosyncrasy, generalize experience, coarsen intimacy. These blockages are multiple and are the results of acquired habits that have become part of the automatic vocal equipment; unnoticed and unknown, they stand between the actor’s voice as it is and as it could be and they will not vanish by themselves.

So the work is not how to do but how to permit: how, in fact, to set the voice free. And since life in the voice springs from emotion, drab and uninspiring technical exercises can never be sufficient. Cicely Berry never departs from the fundamental recognition that speaking is part of a whole: an expression of inner life. She insists on poetry because good verse strikes echoes in the speaker that awaken portions of his deep experience which are seldom evoked in everyday speech. After a voice session with her I have known actors speak not of the voice but of a growth in human relationships. This is a high tribute to work that is the opposite of specialization. Cicely Berry sees the voice teacher as involved in all of a theatre’s work. She would never try to separate the sound of words from their living context. For her the two are inseparable.

This is what makes her book so necessary and valuable.

We would like to thank the following for their kind permission to print the poems and extracts included in this book:

The Trustees of the Hardy Estate, The Macmillan Company of Canada and Macmillan, London and Basingstoke (Copyright 1925 by Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.), for ‘The Going’ from Collected Poems, by Thomas Hardy; the Estate of the late Mrs Frieda Lawrence and Laurence Pollinger Ltd, for ‘Tortoise Shout’ from The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence ed. by Vivian de Sola Pinto and F. Warren Roberts, © 1964, 1971 by Angelo Ravagli and C.M. Weekley, Executors of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Reprinted by permission of the Viking Press, Inc.; The Society of Authors, on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate, for an extract from Man and Superman; Edith Sitwell and Macmillan, London and Basingstoke, for ‘Scotch Rhapsody’ from Collected Poems; J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, the Trustees for the copyrights of the late Dylan Thomas and the New Directions Publishing Corporation, for an extract from Under Milk Wood and ‘Over Sir John’s Hill’ from Collected Poems, by Dylan Thomas; the Macmillan Company of London and Basingstoke and the Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd, for ‘Easter 1916’ from The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats, © 1924 by Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., renewed 1952 by Bertha Georgie Yeats. Reprinted with permission of Macmillan.

We would also like to thank Philip Sayer, photographer, and Lynn Dearth, actress, for the photographs.

ILLUSTRATIONS

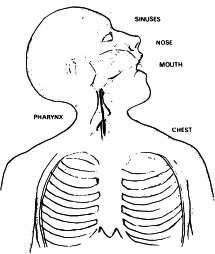

DIAGRAMS IN TEXT

Resonating spaces

Possible rib movement

Good and bad positions on the floor

Bone-prop in the mouth

Position of tongue and its movement

Palate lowered

Position of back of tongue and soft palate

PHOTOGRAPHS

Incorrect posture

Correct posture

Free position on the floor

Tense position of neck and shoulders

Good breathing position

Demonstrating rib movement

Hands stretched above the head

Hands and head hung down

The voice is the means by which, in everyday life, you communicate with other people, and though, of course, how you present yourself – your posture, movement, dress and involuntary gesture – gives an impression of your personality, it is through the speaking voice that you convey your precise thoughts and feelings. This also involves the amount of vocabulary you have at your disposal and the particular words you choose. It follows, therefore, that the more responsive and efficient the voice is, the more accurate it will be to your intentions.

The voice is the most intricate mixture of what you hear, how you hear it, and how you unconsciously choose to use it in the light of your personality and experience. This is complex, as you will see, and is conditioned by four factors:

Environment. As children you learn to speak unconsciously, because of your needs and because you are influenced by the sounds you hear spoken around you. It is an imitative process, so that you start to talk roughly in the same way as the family, or the unit in which you grow up – that is, with a similar tune and with similar vowels and consonants. Possibly the facility with which you convey your needs, and the resistance to or compliance with them at this very early stage, influences the individual use of pitch later – how easily you get what you want, in fact.

‘Ear’. By this I mean the perception of sound. Some people hear sounds more distinctly than others, and some people are more accurate in their production of them. If you have a good ‘ear’ you are open to a greater number of different notes in the voice and to the differing shades of vowels and consonants. This is involved with pleasure in sound and you are aware of a larger spectrum of choice than that provided by your immediate environment. Perhaps you are quicker to see what the voice can do for you.

Physical agility. People have varying degrees of muscular awareness and freedom; this is partly due to environment, though not completely, for it is also tied up with the ease with which you feel you can express yourself in speech, and this of course is to some extent conditioned by education. An introverted and thoughtful person often finds more difficulty in speaking, and does not carry the thought through into the physical process of making speech. There is a kind of reluctance in committing oneself to speech, and this certainly affects the muscles involved in making speech, making their movement less firm and so the result less positive. The less you wish to communicate in speech, the less firmly you use the muscles, and this of course has much to do with confidence. It very rarely has anything to do with laziness. Furthermore, some people think more quickly than they speak, so they trip over words and the result is unfinished. You have to relate the mental intention to the physical action.

Personality. It is in the light of your own self that you interpret the last three conditions, by which you unconsciously form your own voice. So that, though you start by imitation, it is your emotional reaction to your family and environment, your degree of sensitivity to sound, your own individual need to communicate, and your ease or unease in doing so, which are the contributory factors that make you evolve your own completely personal voice and speech.

The voice, therefore, is incredibly sensitive to what is going on around it. In very broad terms, the speech of people who live in country districts is usually slower and more musical than the speech evolved in cities, which is nearly always sharp and glottal and quick – for example, New York, London and Glasgow have very similar speech characteristics. The condition of life conditions the speech, so that the rhythm, pitch and inflection vary accordingly. In the same way, but to an infinitely more subtle degree, personal relationships and the degree of ease with one’s environment and situation continually affect the individual’s voice.

Now the image you have of your own voice is often disturbingly different from the way it actually sounds to other people. It often does not tally with how you think of yourself. Most people are shocked, for instance, when they hear their voice recorded for the first time – it sounds affected, high-pitched, sloppy or just dull. Hearing it recorded is not necessarily a good test, as the mechanism is selective and does not give a whole picture of the voice, just as a photograph, while true, does not give a whole picture of the person. However, you do not hear your own voice as other people hear it, partly because you hear it via the bone conduction and vibrations in your own head, so that you never hear the end product. But, more important, you hear it subjectively – that is, tied up with your own conceptions of sound, of how you would like to sound, and also tied up with what you know you want to convey, for you are on the inside. So the impression you have of your own voice is completely subjective. The result is that you can never be quite sure of the impression you are making, or how accurate your voice is to your intentions – it quite often belies them.

Because it is such a personal statement, criticism of your voice is very close to criticism of yourself, and can easily be destructive. What you need to do is open up the possibilities of your voice and find out what it can do, and try to find a balance between being subjective and objective about it.

This you can do by exercising its physical resources, and perhaps by being bolder in the standards you set yourself. Speaking and using the voice is partly a physical action involving the use of certain muscles, and, just as an athlete goes into training to get his muscles to the required efficiency, or a pianist practises to make his fingers more agile, so if you exercise the muscles involved in using the voice, you can increase its efficiency in sound.

Let us see quite simply how sound is made. To make a sound two factors are needed, something that strikes and something that is struck and which resists the impact to a greater or lesser degree and vibrates accordingly. These vibrations disturb the surrounding air and set up sound waves which you receive through the ear and interpret accordingly. If the sound happens in a room the space will amplify the sound; the emptier the space and the less porous the walls, the more it will be amplified. For instance, a stone building such as a church amplifies sound relatively more than a room which may have materials in it which absorb sound, and where the walls are more porous. Now, a musical sound has a third factor which is a resonant, either a resonating space or resonating material, such as wood, which amplifies the initial sound and sustains it so you hear a note of resultant pitch. Take, for example, a violin: the bow strikes the strings which vibrate according to their length and tautness, these vibrations disturb the surrounding air and set up sound waves which your ear then transmits into sound, and you hear a violin note. The initial sound, however, is amplified and resonated by the wooden case of the violin, and that wooden box sets up its own vibrations which are the harmonics of the original note and which give that note the particular quality of the violin. The sound of one violin can also vary enormously from the sound of another. The quality of the bow and strings, the precise measurements of the box and the quality of its wood, how it is made, and so on, make the resonating vibrations different and so set up slightly different harmonics. Thus, the sound from two different instruments is still recognizable as a note from a violin, though the quality of the note can vary enormously. Furthermore, the way in which the player uses the instrument can make an enormous difference to the sound. The length and tautness of the strings determines the pitch.

You can make an analogy between the violin and the voice. With the voice the breath is the initial impulse, which strikes against the vocal cords in the larynx, which have come together, and makes them vibrate. This sets up sound waves which can then be resonated in the chest, the pharynx or hollow space above the larynx, in the mouth and nose and bones of the face, and the hollow spaces in the head (the sinuses).

Physically, one person varies in size and shape from another person, so each individual voice is intrinsically different. But it is how you use the breath, how you use the resonating spaces, that matters, and it is important, therefore, that you use them as well as possible.

The most useful part of this book will certainly be the exercises, for it is the exercises that matter. It is by doing them, and doing them regularly, that you will increase the physical awareness of your voice and give yourself the freedom to experience the resonances of which you are capable.

The exercises laid out at the back are a synthesis of those in the main part of the book and, as by the end I hope you will have experienced a new awareness of your voice, they will act as a guide and reminder of what you will have found to be necessary and useful to you.

But it is important that you do not look on exercises only as a reassurance of physical prowess. They are a preparation, both physical and for your whole self, which will enable you to respond instinctively to any situation. It is only if, as an actor, you are in a state of total readiness that you are free to be part of the action, which is new every moment. In other words, you do not have to come out of the situation to reflect and think ‘How can I do this?’; you do it at the moment the action arises, because the voice is so free. Exercises should not make you more technical, but more free.

You will also find that doing exercises leads you to know something more of yourself and your attitude towards acting.

It seems to me that the development of the voice goes through three stages. You do exercises for relaxation, breathing and for the increased muscularity of the lips and tongue, all of which free you and open up the voice almost as you do them. You find more power with less effort, more incisiveness, and you hear notes in the voice that you did not know you had, and which are surprising. This is the first stage, and an encouraging one. It is important because it gives proof of the potential sound you have. You can hear the benefit of the exercises on texts which you use to stretch the voice and make it more responsive.

When you come to the second stage, that of applying this freedom and flexibility to the work which you are presenting to an audience, then the business becomes more complex. You will very likely find that the vocal tensions and limitations you normally have are an integral part of the tensions and limitations you have in communicating as an actor, and are therefore not easy to discard. You are therefore forced to question and adjust your whole acting process, for you cannot consider voice by itself, only in relation to the job you are doing.

For example, some actors have an overbalance of head resonance. This comes from tension in the back of the palate and tongue which does not allow the chest notes to reinforce the sound. It also comes, I think, from a mistaken idea that that is where the sound should be placed. This concentration of energy in the head resonators gives the voice a metallic quality which carries well, the actor hears it in his head as having bite and edge, qualities on which he feels he can rely, and his ear is accustomed to that sound. In fact, to the listener’s ear the texture of the voice is restricted, because it is thin and lacks the warmth that the chest notes could give it – its wholeness – and so its possibilities are narrowed. By taking this particular tension away, rooting the voice down, and finding the energy in a different place with less conscious effort, the voice will have much greater flexibility and freedom; it will also have more conviction because it will be more complete. All this the actor may feel when doing the exercises on his own, but when faced with the situation of the audience it is extremely difficult for him to believe that he is being as positive when he is not feeling the usual effort. He feels lost without the tension on which he has relied, because this tension was part of his emotional make-up and his way of committing himself to an audience, and perhaps of convincing himself. It then becomes more than a simple question of voice, for the rooted voice is stronger and more positive – it calls into question your judgment of the amount of energy needed to communicate, and where that energy should be found. Whatever the problem, it takes time to believe that freedom works.

It is obviously difficult to talk about voice in general terms, because the voice is absolutely personal to the individual. It is the means by which you communicate your inner self, and there are many factors, both physical and psychological, which have contributed to its making, so that the danger is that you will interpret instructions subjectively. You therefore have to discover a very firm basis of understanding, a common understanding, a norm, and this you can do by the experience of exercises and the precise movements of muscles, and their effect on the voice.

Tensions and limitations always come from a lack of trust in yourself: either you are over-anxious to communicate or to present an image, or you want to convince an audience of something about yourself. Even the experienced actor often limits himself by relying too much on what he knows works and is effective, and this in itself is a lack of freedom. Certainly, an actor has to find what means he can rely on to communicate to his audience, that is part of the craft, but if he holds on to the same means to find his energy and truth he then becomes predictable. He fixes, and what started as something which was good can end so easily as a manner – the same way of dealing with a situation. An actor with an interesting voice who uses it well can still end up with his audience knowing how he is going to sound, so there is no surprise. This has a lot to do with lack of trust, because it takes trust to start each part with a clean slate, as it were – in other words, with no preconceived ideas of how it should sound, no holding on to the voice that you know. It is only by being in a state of readiness that the voice will be liberated.

This second stage, therefore, often involves discarding what is comfortable. It involves persevering with the exercises so that we learn about energy – where our energy lies and how to use it. All unnecessary tension is wasted energy. More than this, if you do not use enough energy you fail to reach your audience, but if you use too much you disperse it by using too much breath, bursting out on consonants, by being too loud, and so on. The audience then tends to recoil, because you are pushing the energy, manufacturing it, and not finding it within yourself, and this has to do with pushing out emotion and underlining what you feel. In real life you step back from the person who is over-anxious, over-enthusiastic, the person who gets you in a corner when he talks to you, and it is the same with the actor’s relationship with his audience. What you are attempting to find is the right physical balance in the voice, which of course helps the acting balance – the more often you find it, the easier it is to recall it. It is in persevering with the voice over a period of time that you get the essential awareness of the separateness of muscles and what they contribute, and this is when voice finds its own intrinsic quality, involving no effort. It is a two-way process, and a rather marvellous one, you know what you want to communicate, but in the physical act of making sound, meanings take on a new dimension.

In short, you are looking for the energy in the muscles themselves, and when you find that energy you do not have to push it out, it releases itself. You do not then have to push your emotion out, it is released through the voice. When you can tie this up with your intentions as an actor you have found what you are after, a unity of physical and emotional energy, and you are then at the third stage. Here the aim is only to simplify. Quite suddenly the very simple exercises take on a particular purpose, and you are round again to the view that the straightforward exercises for relaxation, breathing and the muscularity of the lips and tongue are your basis and your security.

So, though in the end getting the best out of your voice is a straight matter of doing exercises, you often have to go through a complex phase to know why the exercises are needed. Because you cannot divorce voice from communication, you have to sort out the problems and needs of communication before the exercises can be effective. And communication to an audience is complex and elusive, its validity changes as you change and with the different material you are using. The aim is always clarity, but you can fog that clarity by allowing too much feeling through, by over-explaining, by presenting what you think you ought to present, what you think is interesting, that is to say, by selecting the part of yourself which you think is most acceptable. And you can fog it by tension, which is always a matter of compensating for something you think you lack – size, for instance. A slightly-built actor will very often push his voice down in a false way in an effort to get weight, but this only limits and diminishes, and he has to learn to trust in his own size. You continually signal what you would like people to see of you, and when you signal that you feel, that you understand, then you fog real communication.

I think one of the greatest fears of the actor is that of not being interesting. This really need never be a fear because everyone is interesting in that he is himself. When you get to the point which says ‘This is me; it will change, and perhaps improve, but this is me at this moment’, then the voice will become open. Certainly, the more integrated the actor is the more he realizes the value of specific exercises. That is why I said that our common ground was the experience of the voice through the movement of muscles, and each person has to apply this experience for himself. The more you do this, the more objective you will become.

The primary object then is to open up the possibilities of the voice, and to do this you have to start listening. I do not mean listening to the external sound of your voice; I mean very specially listening for the vocal resource you have, listening for what you as a person require to say, and listening for what the text contains. And this takes time and stillness. You are conditioned so much by what you think good sound should be, by what you would like the result to be, which is often too logical anyway, that you limit the range of notes you use and stop your instinctive responses. You get ready with your sound before you have really listened to what is being said to you, or before you have really listened to what your text says. This again is a form of anxiety which makes you rush into things. You have to learn to listen afresh in every moment, and to keep questioning what you are saying; only by doing this can you keep the voice truly alive.

A great deal of voice work is done on what, to my mind, is a negative basis – this is, ‘correcting’ the voice, making it ‘better’, with all the social and personal implications of that word, somehow making it seem that you are not quite good enough. Emphasis has been on ironing out not-quite-standard vowels, neatening consonants, projecting the voice, and getting a full, consistent tone, with the underlying inference that there is a way that you should sound, a way of speaking lines. Naturally, the voice must be able to give pleasure, and it can only do so if it is well tuned and rhythmically aware, and this involves well-defined vowels and consonants. Additionally, however, you must always build on the vitality which is there in your own voice, increase your awareness of its music so that it can fulfil the demands of a text, and make the vowels and consonants more accurate because that way you are alive to the accuracy of the meaning. A corrective attitude to voice reduces the actor to using it ‘right’, and keeps him within the conventional tramlines of good speech. This way it cannot be accurate to himself. It is also inhibiting, and makes much acting dull. You want to open the voice out so that its music can match the music of what you are saying, and make the vowels and consonants sharp so you can point the meaning.

I think many young, interesting actors shy away from working on voice because of this restrictive attitude. Quite understandably they do not want something so personal interfered with and sounding well produced; they distrust it for they fear their individuality will be lost, and in any case it is not relevant to what they feel. This kind of attitude is a relic of all the associations of class which attached to English speech, thankfully now becoming less significant. If you have any sort of regional accent or slightly ‘off-gent’ speech, subconsciously there is the fear that if you make it standard you will lose some of your vitality, and consequently some of your virility, and this is a very real barrier. It may also seem as though you are betraying your background. Nevertheless, if you hold on to a way of speaking for the wrong reason you limit your voice, and therefore you limit what it can convey. If you limit it consciously, then the voice will not be quite true, and it follows that the acting will not be quite right. It is as crucial as that. Limitations keep the audience attention on the actor and not on the character he is playing.