Roundworld, our Earth, is in trouble again. And this time it looks fatal. After occidentally creating it in the first place, the wizards of Unseen University feel vaguely responsible for its safety. So when they discover that history has come adrift and humanity is on a collision course with extinction, they take drastic action.

A certain Charles Darwin has written the wrong book and The Origin of Species is never published. Victorian England has stagnated and the pace of progress has slowed right down. The wizards need to figure out what went wrong and change history back.

The Science of Discworld III: Darwin’s Watch takes us on a fascinating exploration of evolution, alternate realities and time travel. Science chapters cleverly weave through the story of how the wizards of Discworld struggle to put humanity back on track, and save us from destruction.

Sir Terry Pratchett was the acclaimed creator of the global bestselling Discworld series; the first Discworld book, The Colour of Magic, was published in 1983. In all, he was the author of fifty bestselling books. His novels have been widely adapted for stage and screen, and he was the winner of multiple prizes, including the Carnegie Medal, as well as being awarded a knighthood for services to literature. Worldwide sales of his books now stand at 75 million. He died in March 2015.

Professor Ian Stewart is the author of many popular science books and appears frequently on radio and television. He is an Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick. He was awarded the Michael Faraday Medal for furthering the public understanding of science, and in 2001 became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Dr Jack Cohen is an internationally renowned reproductive biologist. He has retired to a small thatched cottage in Dorset. He writes, ponders, and plays with microscopes in a rather grand ‘garden shed’. He also throws boomerangs, but doesn’t catch them as often as he used to. In addition, he still enjoyes lecturing and continues to have a passion for the public understanding of science.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

COVER

ABOUT THE BOOK

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ALSO BY TERRY PRATCHETT, IAN STEWART & JACK COHEN

TITLE PAGE

EPIGRAPH

CONCERNING ROUNDWORLD

1. ANY OTHER BUSINESS

2. PALEY’S WATCH

3. THEOLOGY OF SPECIES

4. PALEY ONTOLOGY

5. THE WRONG TROUSERS OF TIME

6. BORROWED TIME

7. THE FISH IS OFF

8. FORWARD TO THE PAST

9. AVOIDING MADEIRA

10. WATCH-22

11. WIZARDS ON THE WARPATH

12. THE WRONG BOOK

13. INFINITY IS A BIT TRICKY

14. ALEPH-UMPTYPLEX

15. AUDITORS OF REALITY

16. MANIFEST DESTINY

17. GALÁPAGOS ENCOUNTER

18. STEAM ENGINE TIME

19. LIES TO DARWIN

20. THE SECRETS OF LIFE

21. NOUGAT SURPRISE

22. FORGET THE FACTS

23. THE GOD OF EVOLUTION

24. A LACK OF SERGEANTS

25. THE ENTANGLED BANK

AFTERTHOUGHT

INDEX

COPYRIGHT

In crossing a heath, suppose I … found a watch upon the ground … The inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker.

Divine Design, the conscious process of creation, which Paley discovered, and which we now know is the explanation for the existence and purposeful form of all life, always has purpose in mind. If the Deity can be said to play the role of Watchmaker in nature, He is an all-seeing Watchmaker.

There is grandeur in this view of life … and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

There is grandeur in this view of life … and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Natural selection, the blind, unconscious automatic process which Darwin discovered, and which we now know is the explanation for the existence and apparently purposeful form of all life, has no purpose in mind … If it can be said to play the role of watchmaker in nature, it is the blind watchmaker.

In crossing a heath, suppose I found a watch upon the ground. The inference, I think, is inevitable. Some careless chronometric surveyor must have dropped it.

DISCWORLD IS REAL. It’s the way worlds should work. Admittedly, it is flat and goes through space on the backs of four elephants which stand on the shell of a giant turtle, but consider the alternatives.

Consider, for example, a globular world, a mere crust upon an inferno of molten rock and iron. An accidental world, made of the wreckage of old stars, the home of life which, nevertheless, in a most unhomely fashion, is regularly scythed from its surface by ice, gas, inundation or falling rocks travelling at 20,000 miles an hour.

Such an improbable world, and the entire cosmos that surrounds it, was in fact accidentally created by the wizards of Unseen University.1 It was the Dean of Unseen University who in fact destabilised the raw firmament by fiddling with it, possibly leading to the belief, if folk memory extends to sub-sub-sub-sub-atomic particle level, that it was indeed all done by somebody with a beard.

Infinite in size on the inside, but about a foot across on the outside, the universe of Roundworld is now kept in a glass globe in UU, where it has been the source of much interest and concern.

Mostly, it’s the source of concern. Alarmingly, it contains no narrativium.

Narrativium is not an element in the accepted sense. It is an attribute of every other element, thus turning them into, in an occult sense, molecules. Iron contains not just iron, but also the story of iron, the history of iron, the part of iron that ensures that it will continue to be iron and has an iron-like job to do and is not, for example, cheese. Without narrativium, the cosmos has no story, no purpose, no destination.

Nevertheless, under the ancient magical rule of As Above, So Below, the crippled universe of Roundworld strives at some level to create its own narrativium. Iron seeks out other iron. Things spin. In the absence of any gods to do the creating of life, life has managed, against the odds, to create itself. Yet the humans who have evolved on the planet believe in their hearts that there are such things as gods, magic, cosmic purpose and million-to-one chances that crop up nine times out of ten. They seek stories in the world which the world, regrettably, is not equipped to tell.

The wizards, feeling somewhat guilty about this, have intervened several times in the history of Roundworld when it seemed to them to be on the wrong track. They encouraged fish (or fish-like creatures) to leave the seas, they visited the proto-civilisations of dinosaur-descendants and crabs, they despaired at the way ice and falling comets wiped out higher life forms so often – and they found some monkeys who were obsessed with sex and were quick learners, especially if sex was involved or could, by considerable ingenuity, be made to be involved.

Again the wizards intervened, teaching them that fire was not for having sex with and in general encouraging them to get off the planet before the next big extinction.

In this they have all been guided by Hex, UU’s magical thinking engine, which is immensely powerful in any case, and with Roundworld, which from Hex’s point of view is a mere sub-routine of Discworld and is practically godlike, although more patient.

The wizards think they have sorted it all out. The monkeys have learned about their permanently threatened world via a type of technomancy called Science and may yet escape frozen doom.

And yet …

The thing about best laid plans is that they don’t often go wrong. They sometimes go wrong, but not often, because of having been, as aforesaid, the best laid. The kind of plans laid by wizards, who barge in, shout a lot, try to sort it all out by lunchtime and hope for the best, on the other hand … well, they go wrong almost instantly.

There is a kind of narrativium on Roundworld, if you really look.

On Discworld, the narrativium of a fish tells it that it is a fish, was a fish, and will continue to be a fish. On Roundworld, something inside a fish tells it that it is a fish, was a fish … and might eventually be something else …

… perhaps.

1 The greatest school of magic on the Discworld. But surely you know this?

IT WAS RAINING. This would, of course, be good for the worms.

IT WAS RAINING. This would, of course, be good for the worms.

Through the trickles that coursed down the window Charles Darwin stared at the garden.

Worms, thousands of them, out there under the soft rain, turning the detritus of winter into loam, building the soil. How … convenient.

The ploughs of God, he thought, and winced. It was the harrows of God that plagued him now.

Strange how the rustle of the rain sounds very much like people whispering …

At which point, he became aware of the beetle. It was climbing up the inside of the window, a green and blue tropical jewel.

There was another one, higher up, banging fruitlessly against the pane.

One landed on his head.

The air filled up with the rattle and slither of wings. Entranced, Darwin turned to look at the glowing cloud in the corner of the room. It was forming a shape …

It is always useful for a university to have a Very Big Thing. It occupies the younger members, to the relief of their elders (especially if the VBT is based at some distance from the seat of learning itself) and it uses up a lot of money which would otherwise only lie around causing trouble or be spent by the sociology department or, probably, both. It also helps in pushing back boundaries, and it doesn’t much matter what boundaries these are, since as any researcher will tell you it’s the pushing that matters, not the boundary.

It’s a good idea, too, if it’s a bigger VBT than anyone else’s and, in particular, since this was Unseen University, the greatest magical university in the world, if it’s a bigger one than the one those bastards are building at Braseneck College.

‘In fact,’ said Ponder Stibbons, Head of Inadvisably Applied Magic, ‘theirs is really only a QBT, or Quite Big Thing. Actually, they’ve had so many problems with it, it’s probably only a BT!’

The senior wizards nodded happily.

‘And ours is certainly bigger, is it?’ said the Senior Wrangler.

‘Oh, yes,’ said Stibbons. ‘Based on what I can determine from chatting to the people at Braseneck, ours will be capable of pushing boundaries twice as big up to three times as far.’

‘I hope you haven’t told them that,’ said the Lecturer in Recent Runes. ‘We don’t want them building a … a … an EBT!’

‘A what, sir?’ said Ponder politely, his tone saying, ‘I know about this sort of special thing and I’d rather you did not pretend that you do too.’

‘Um … an Even Bigger Thing?’ said Runes, aware that he was edging into unknown territory.

‘No, sir,’ said Ponder, kindly. ‘The next one up would be a Great Big Thing, sir. It’s been postulated that if we could ever build a GBT, we would know the mind of the Creator.’

The wizards fell silent. For a moment, a fly buzzed against the high, stone-mullioned window, with its stained-glass image of Archchancellor Sloman Discovering the Special Theory of Slood, and then, after depositing a small flyspeck on Archchancellor Sloman’s nose, exited with precision though a tiny hole in one pane which had been caused two centuries ago when a stone had been thrown up by a passing cart. Originally the hole had stayed there because no one could be bothered to have it fixed, but now it stayed there because it was traditional.

The fly had been born in Unseen University and because of the high, permanent magical field, was far more intelligent that the average fly. Strangely, the field never had this effect on wizards, perhaps because most of them were more intelligent than flies in any case.

‘I don’t think we want to do that, do we?’ said Ridcully.

‘It might be considered impolite,’ agreed the Chair of Indefinite Studies.

‘Exactly how big would a Great Big Thing be?’ said the Senior Wrangler.

‘The same size as the universe, sir,’ said Ponder. ‘Every particle of the universe would be modelled within it, in fact.’

‘Quite big, then …’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And quite hard to find room for, I should imagine.’

‘Undoubtedly, sir,’ said Ponder, who had long ago given up trying to explain Big Magic to the rest of the senior faculty.

‘Very well, then,’ said Archchancellor Ridcully. ‘Thank you for your report, Mister Stibbons.’ He sniffed. ‘Sounds fascinatin’. And the next item: Any Other Business.’ He glared around the table. ‘And since there is no other busi—’

‘Er …’

This was a bad word at this point. Ridcully did not like committee business. He certainly did not like any other business.

‘Well, Rincewind?’ he said, glaring down the length of the table.

‘Um …’ said Rincewind. ‘I think that’s Professor Rincewind, sir?’

‘Very well, professor,’ said Ridcully. ‘Come on, it’s past time for Early Tea.’

‘The world’s gone wrong, Archchancellor.’

As one wizard, everyone looked out at what could be seen of the world through Archchancellor Sloman Discovering the Special Theory of Slood.

‘Don’t be a fool, man,’ said Ridcully. ‘The sun’s shining! It’s a nice day!’

‘Not this world, sir,’ said Rincewind. ‘The other one.’

‘What other one?’ said the Archchancellor, and then his expression changed.

‘Not—’ he began.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Rincewind. ‘That one. It’s gone wrong. Again.’

Every organisation needs someone to do those jobs it doesn’t want to do or secretly thinks don’t need doing. Rincewind had nineteen of them now, including Health and Safety Officer.1

It was as Egregious Professor of Cruel and Unusual Geography that he was responsible for the Globe. These days, it was on his desk out in the gloomy cellar passage where he worked, work largely consisting of waiting until people gave him some cruel and unusual geography to profess.

‘First question,’ said Ridcully, as the faculty swept along the dank flagstones. ‘Why are you working out here? What’s wrong with your office?’

‘It’s too hot in my office, sir,’ said Rincewind.

‘You used to complain it was too cold!’

‘Yes, sir. In the winter it is. Ice freezes on the walls, sir.’

‘We give you plenty of coal, don’t we?’

‘Ample, sir. One bucket per day per post held, as per tradition. That’s the trouble, really. I can’t get the porters to understand. They won’t give me less coal, only no coal at all. So the only way to be sure of staying warm in the winter is to keep the fire going all summer, which means it’s so hot in there that I can’t work in – don’t open the door, sir!’

Ridcully, who’d just opened the office door, slammed it again, and wiped his face with a handkerchief.

‘Snug,’ he said, blinking the sweat out of his eyes. Then he turned to the little globe on the desk behind him.

It was about a foot across, at least on the outside. Inside, it was infinite; most wizards have no problem with facts of this sort. It contained everything there was, for a given value of ‘contained everything there was’, but in its default state it focused on one tiny part of everything there was, a small planet which was, currently, covered in ice.

Ponder Stibbons swivelled the omniscope that was attached to the base of the glass dome, and stared down at the little frozen world. ‘Just debris at the equator,’ he reported. ‘They never built the big skyhook thing that allowed them to leave.2 There must have been something we missed.’

‘No, we sorted it all out,’ said Ridcully. ‘Remember? All the people did get away before the planet froze.’

‘Yes, Archchancellor,’ said Stibbons. ‘And, then again, no.’

‘If I ask you to explain that, would you tell me in words I can understand?’ said Ridcully.

Ponder stared at the wall for a moment. His lips moved as he tried out sentences. ‘Yes,’ he said at last. ‘We changed the history of the world, sending it towards a future where the people could escape before it froze. It appears that something has happened to change it back since then.’

‘Again? Elves did it last time!’3

‘I doubt if they’ve tried again, sir.’

‘But we know the people left before the ice,’ said the Lecturer in Recent Runes. He looked from face to face, and added uncertainly, ‘Don’t we?’

‘We thought we knew before,’ said the Dean, gloomily.

‘In a way, sir,’ said Ponder. ‘But the Roundworld universe is somewhat … soft and mutable. Even though we can see a future happen, the past can change so that from the point of view of Roundworlders it doesn’t. It’s like … taking out the last page of a book and putting a new one in. You can still read the old page, but from the point of view of the characters, the ending has changed, or … possibly not.’

Ridcully slapped him on the back. ‘Well done, Mr Stibbons! You didn’t mention quantum even once!’ he said.

‘Nevertheless, I suspect it may be involved,’ sighed Ponder.

1 The N’tuitiv tribe of Howondaland created the post of Health and Safety Officer even before the post of Witch Doctor, and certainly before taming fire or inventing the spear. They hunt by waiting for animals to drop dead, and eat them raw.

2 See The Science of Discworld (Ebury Press, 1999, revd 2000).

3 See The Science of Discworld II (Ebury Press, 2002).

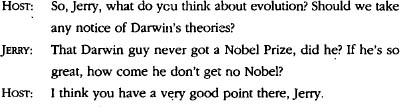

THE SCENE: A radio chat-show in the Bible Belt of the United States, a few years ago. The host is running a phone-in about evolution, a concept that is anathema to every God-fearing southern fundamentalist. The conversation runs something like this:

THE SCENE: A radio chat-show in the Bible Belt of the United States, a few years ago. The host is running a phone-in about evolution, a concept that is anathema to every God-fearing southern fundamentalist. The conversation runs something like this:

Such a conversation did occur, and the host was not being ironic. But Jerry’s point is not quite the knock-down argument he thought it was. Charles Robert Darwin died in 1882. The first Nobel Prize was awarded in 1901.

Of course, well-meaning people are often ignorant about fine points of historical detail, and it is unfair to hold that against them. But it is perfectly fair to hold something else against them: the host and his guest didn’t have their brains in gear. After all, why were they having that discussion? Because, as every God-fearing southern fundamentalist knows, virtually every scientist views Darwin as one of the all-time greats. It was this assertion, in fact, that Jerry was attempting to shoot down. Now, it should be pretty obvious that winners of Nobel prizes (for science) are selected by a process that relies heavily on advice from scientists. And those, we already know, are overwhelmingly of the opinion that Darwin was somewhere near the top of the scientific tree. So if Darwin didn’t get a Nobel, it couldn’t have been (as listeners were intended to infer) because the committee didn’t think much of his work. There had to be another reason. As it happens, the main reason was that Darwin was dead.

As this story shows, evolution is still a hot issue in the Bible Belt, where it is sometimes known as ‘evilution’ and generally viewed as the work of the Devil. More sophisticated religious believers – especially European ones, among them the Pope – worked out long ago that evolution poses no threat to religion: it is simply how God gets things done, in this case, the manufacture of living creatures. But the Bible-Belters, in their unsophisticated fundamentalist manner, recognise a threat, and they’re right. The sophisticated reconciliation of evolution with God is a wishy-washy compromise, a cop-out. Why? Because evolution knocks an enormous hole in what otherwise might be the best argument yet devised for convincing people of the existence of God, and that is the ‘argument from design’.1

The universe is awesome in its size, astonishing in its intricacy. Every part of it fits neatly with every other part. Consider an ant, an anteater, an antirrhinum. Each is perfectly suited to its role (or ‘purpose’). The ant exists to be eaten by anteaters, the anteater exists to eat ants, and the antirrhinum … well, bees like it, and that’s a good thing. Each organism shows clear evidence of ‘design’, as if it had been made specifically to carry out some purpose. Ants are just the right size for anteaters’ tongues to lick up, anteaters have long tongues to get into ants’ nests. Antirrhinums are exactly the shape to be pollinated by visiting bees. And if we observe design, then surely a designer can’t be far away.

Many people find this argument compelling, especially when it is developed at length and in detail, and ‘designer’ is given a capital ‘D’. But Darwin’s ‘dangerous idea’, as Daniel Dennett characterised it in his book with that title, puts a very big spoke into the wheel of cosmic design. It provides an alternative, very plausible, and apparently simple process, in which there is no role for design and no need for a designer. Darwin called that process ‘natural selection’; nowadays we call it ‘evolution’.

There are many aspects of evolution that scientists don’t yet understand. The details behind Darwin’s theory are still up for grabs, and every year brings new shifts of opinion as scientists try to improve their understanding. Bible-Belters understand even less about evolution, and they typically distort it into a caricature: ‘blind chance’. They have no interest whatsoever in improving their understanding. But they do understand, far better than effete Europeans, that the theory of evolution constitutes a very dangerous attack on the psychology of religious belief. Not on its substance (because anything that science discovers can be attributed to the Deity and viewed as His mechanism for bringing the associated events about) but on its attitude. Once God is removed from the day-to-day running of the planet, and installed somewhere behind DNA biochemistry and the Second Law of Thermodynamics, it is no longer so obvious that He must be fundamental to people’s daily lives. In particular, there is no special reason to believe that He affects those lives in any way, or would wish to, so the fundamentalist preachers could well be out of a job. Which is how Darwin’s lack of a Nobel can become a debating point on American local radio. It is also the general line along which Darwin’s own thinking evolved – he began his adult life as a theology student and ended it as a somewhat tormented agnostic.

Seen from outside, and even more so from within, the process of scientific research is disorderly and confusing. It is tempting to deduce that scientists themselves are disorderly and confused. In a way, they are – that’s what research involves. If you knew what you. were doing it wouldn’t be research. But that’s just an apology, and there are better reasons for expecting, indeed, for valuing, that kind of confusion. The best reason is that it’s an extremely effective way of understanding the world, and having a fair degree of confidence in that understanding.

In her book Defending Science – Reason the philosopher Susan Haack illuminates the messiness of science with a simple metaphor, the crossword puzzle. Enthusiasts know that solving a crossword puzzle is a messy business. You don’t solve the clues in numerical order and write them in their proper place, converging in an orderly manner to a correct solution, unless, perhaps, it’s a quick crossword and you’re an expert. Instead, you attack the clues rather randomly, guided only by a vague feeling of which ones look easiest to solve (some people find anagrams easy, others hate them). You cross-check proposed answers against others, to make sure everything fits. You detect mistakes, rub them out, write in corrections.

It may not sound like a rational process, but the end result is entirely rational, and the checks and balances – do the answers fit the clues, do the letters all fit together? – are stringent. A few mistakes may still survive, where alternative words fit both the clue and the words that intersect them, but such errors are rare (and arguably aren’t really errors, just ambiguity on the part of the compiler).

The process of scientific research, says Haack, is rather like solving a crossword puzzle. Solutions to nature’s riddles arrive erratically and piecemeal. When they are cross-checked against other solutions to other riddles, sometimes the answers don’t fit, and then something has to be changed. Theories that were once thought to be correct turn out to be nonsense and are thrown out. A few years ago, the best explanation of the origin of stars had one small flaw: it implied that the stars were older than the universe that contained them. At any given time, some of science’s answers appear to be very solid, some less so, some are dubious … and some are missing entirely.

Again, it doesn’t sound like a rational process, but it leads to a rational result. Indeed, all that cross-checking, backtracking, and revision increases our confidence in the result. Remembering, always, that nothing is proved to the hilt, nothing is final.

Critics often use this confused and confusing process of discovery as a reason to discredit science. Those stupid scientists can’t even agree among themselves, they keep changing their minds, everything they say is provisional – why should anyone else believe such a muddle? They thereby misrepresent one of science’s greatest strengths by portraying it as a weakness. A rational thinker must always be prepared to change his or her mind if the evidence requires it. In science, there is no place for dogma. Of course, many individual scientists fall short of this ideal; they are only human. Entire schools of scientific thought can get trapped in an intellectual blind alley and go into denial. On the whole, though, the errors are eventually exposed – by other scientists.

Science is not the only area of human thought to develop in this flexible way. The humanities do similar things, in their own manner. But science imposes this kind of discipline upon itself more strongly, more systematically, and more effectively, than virtually any other style of thinking. And it uses experiments as a reality check.

Religions, cults, and pseudoscientific movements do not behave like that. It is extremely rare for religious leaders to change their minds about anything that is already in their Holy Book. If your beliefs are held to be revealed truth, direct from the mouth of God, it’s tricky to admit to errors. All the more credit to the Catholics, then, for admitting that in Galileo’s day they got it wrong about the Earth being the centre of the universe, and until recently they got it wrong about evolution.

Religions, cults and pseudoscientific movements have a different agenda from science. Science, at its best, keeps lines of enquiry open. It is always seeking new ways to test old theories, even when they seem well established. It doesn’t just look at the geology of the Grand Canyon and settle on the belief that the Earth is hundreds of millions of years old, or older. It cross-checks by taking new discoveries into account. After radioactivity was discovered, it became possible to obtain more accurate dates for geological events, and to compare those with the apparent record of sedimentation in the rocks. Many dates were then revised. When continental drift came in from left field, entirely new ways to find those dates arrived, and were quickly used. More dates were revised.

Scientists – collectively – want to find their mistakes, so that they can get rid of them.

Religions, cults, and pseudoscientific movements want to close down lines of enquiry. They want their followers to stop asking questions and accept the belief system. The difference is glaring. Suppose, for instance, that scientists became convinced that there was something worth taking seriously in the theories of Erich von Däniken, that ancient ruins and structures must have been the work of visiting aliens. They would then start asking questions. Where did the aliens come from? What sort of spaceships did they have? Why did they come here? Do ancient inscriptions suggest one kind of alien or many? What is the pattern to the visitations? Whereas believers in von Däniken’s theories are satisfied with generic aliens, and ask no more. Aliens explain the ruins and structures – that’s cracked it, problem solved.

Similarly, to early proponents of divine design and their modern reincarnations creationism and ‘intelligent design’, the latest quasi-religious fad, once we know that living creatures were created (either by God, an alien, or an unspecified intelligent designer) then the problem is solved and we need look no further. We are not encouraged to look for evidence that might disprove our beliefs. Just things that confirm them. Accept what we tell you, don’t ask questions.

Ah, yes, but science discourages questions too, say the cults and religions. You don’t take our views seriously, you don’t allow that sort of question. You try to stop us putting our ideas into school science lessons as alternatives to your world view.

To some extent, that’s true – especially the bit about science lessons. But they are science lessons, so they should be teaching science. Whereas the claims of the cults and the creationists, and the closet theists who espouse intelligent design, are not science. Creationism is simply a theistic belief system and offers no credible scientific evidence whatsoever for its beliefs. Evidence for alien visitations is weak, incoherent, and most of it is readily explained by entirely ordinary aspects of ancient human culture. Intelligent design claims evidence for its views, but those claims fall apart under even casual scientific scrutiny, as documented in the 2004 books Why Intelligent Design Fails, edited by Matt Young and Taner Edis, and Debating Design, edited by William Dembski and Michael Ruse. And when people (none of the above, we hasten to point out) claim that the Grand Canyon is evidence for Noah’s flood – a notorious recent incident – it’s not terribly hard to prove them wrong.

The principle of free speech implies that these views should not be suppressed, but it does not imply that they should be imported into science lessons, any more than scientific alternatives to God should be imported into the vicar’s Sunday sermon. If you want to get your world view into the science lesson, you’ve got to establish its scientific credentials. But because cults, religions and alternative belief systems stop people asking awkward questions, there’s no way they can ever get that kind of evidence. It’s not only chance that is blind.

The scientific vision of the planet that is currently our only home, and of the creatures with which we share it and the universe around it, has attained its present form over thousands of years. The development of science is mostly an incremental process, a lake of understanding filled by the constant accumulation of innumerable tiny raindrops. Like the water in a lake, the pool of understanding can also evaporate again – for what we think we understand today can be exposed as nonsense tomorrow, just as what we thought we understood yesterday is exposed as nonsense today. We use the word ‘understanding’ rather than, ‘knowledge’ because science is both more than, and less than a collection of immutable facts. It is more, in that it encompasses organising principles that explain what we like to think of as facts: the strange paths of the planets in the sky make perfect sense once you understand that planets are moved by gravitational forces, and that these forces obey mathematical rules. It is less, because what may look like a fact today may turn out tomorrow to have been a misinterpretation of something else. On Discworld, where obvious things tend to be true, a tiny and insignificant Sun does indeed revolve round the grand, important world of people. We used to think our world was like that too: for centuries, it was a ‘fact’, and an obvious one, that the Sun revolved round the Earth.

The big organising principles of science are theories, coherent systems of thought that explain huge numbers of otherwise isolated facts, which have survived strenuous testing deliberately designed to break them if they do not accord with reality. They have not been merely accepted as some act of scientific faith: instead, people have tried to falsify them – to prove them wrong – but have so far failed. These failures do not prove that the theory is true, because there are always new sources of potential discord. Isaac Newton’s theory of gravitation, in conjunction with his laws of motion, was – and still is – good enough to explain the movements of the planets, asteroids and other bodies of the solar system in intricate detail, with high accuracy. But in some contexts, such as black holes, it has now been replaced by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Wait a few decades, and something else will surely replace that. There are plenty of signs that all is not well at the frontiers of physics. When cosmologists have to postulate bizarre ‘dark matter’ to explain why galaxies don’t obey the known laws of gravity, and then throw in even weirder ‘dark energy’ to explain why galaxies are moving apart at an increasing rate, and when the independent evidence for these two powers of darkness is pretty much non-existent, you can smell the coming paradigm shift.

Most science is incremental, but some is more radical. Newton’s theory was one of the great breakthroughs of science – not a shower of rain disturbing the surface of the lake, but an intellectual storm that unleashed a raging torrent. Darwin’s Watch is about another intellectual storm: the theory of evolution. Darwin did for biology what Newton had done for physics, but in a very different way. Newton developed mathematical equations that let physicists calculate numbers and test them to many decimal places; it was a quantitative theory. Darwin’s idea is expressed in words, not equations, and it describes a qualitative process, not numbers. Despite that, its influence has been at least as great as Newton’s, possibly even greater. Darwin’s torrent still rages today.

Evolution, then, is a theory, one of the most influential, far-reaching and important theories ever devised. In this context, it’s worth pointing out that the word ‘theory’ is often used in a quite different sense, to mean an idea that is proposed in order to be tested. Strictly speaking, the word that should be used here is ‘hypothesis’, but that’s such a fussy, pedantic-sounding word that people tend to avoid it. Even scientists, who should know better. ‘I have a theory,’ they say. No, you have a hypothesis. It will take years, possibly centuries, of stringent tests, to turn it into a theory.

The theory of evolution was once a hypothesis. Now it is a theory. Detractors seize on the word and forget its dual use. ‘Only a theory,’ they say dismissively. But a true theory cannot be so easily dismissed, because it has survived so much rigorous testing. In this respect there is far more reason to take the theory of evolution seriously than any explanation of life that depends on, say, religious faith, because falsification is not high on the religious agenda. Theories, in that sense, are the best established, most credible parts of science. They are, by and large, considerably more credible than most other products of the human mind. So what these people are thinking of when they chant their dismissive slogan should actually be ‘only a hypothesis’.

That was a defensible position in the early days of the theory of evolution, but today it is merely ignorant. If anything can be a fact, evolution is. It may have to be inferred from clues deposited in the rocks, and more recently by comparing the DNA codes of different creatures, rather than being seen directly with the naked eye in real time, but you don’t need an eyewitness account to make logical deductions from evidence. The evidence, from several independent sources (such as fossils and DNA), is overwhelming. Evolution has been established so firmly that our planet makes no sense at all without it. Living creatures can, and do, change over time. The fossil record shows that they have changed substantially over long periods of time, to the extent that entirely new species have arisen. Smaller changes can be observed today, over periods as short as a year, or mere days in bacteria.

Evolution happens.

What remains open to dispute, especially among scientists, is how evolution happens. Scientific theories themselves evolve, adapting to fit new observations, new discoveries, and new interpretations of old discoveries. Theories are not carved in tablets of stone. The greatest strength of science is that when faced with sufficient evidence, scientists change their minds. Not all of them, for scientists are human and have the same failings as the rest of us, but enough of them to allow science to improve.

Even today there are diehards – not a majority, despite the noise they make, but a significant minority – who deny that evolution has ever occurred. Most of them are American, because a quirk of history (coupled with some idiosyncratic tax laws) has made evolution into a major educational issue in the United States. There, the battle between Darwin’s followers and his opponents is not just about the intellectual high ground. It is about dollars and cents, and it is about who influences the hearts and minds of the next generation. The struggle masquerades as a religious and scientific one, but its essence is political. In the 1920s four American states (Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee) made it illegal to teach children about evolution in public schools. This law remained in place for nearly half a century: it was finally banned by the Supreme Court in 1968. This has not stopped advocates of ‘creation science’ from trying to find ways round that decision, or even to get it reversed. Largely, however, they have failed, and one reason is that creation ‘science’ is not science; it lacks intellectual rigour, it fails objective tests, and at times it is plain nutty.

It is possible to maintain that God created the Earth, and no one can prove you wrong. In that sense, it is a defensible thing to believe. Scientists may feel that this ‘explanation’ doesn’t greatly help us understand anything, but that’s their problem; for all anyone can prove, it could have happened that way. But it is not sensible to follow the Anglo-Irish prelate James Ussher’s biblical chronology and maintain that the act of creation happened in 4004 BC, because there is overwhelming evidence that our planet is far older than that – 4.5 billion years rather than 6000. Either God is deliberately trying to mislead us (which is conceivable, but does not fit well with the usual religious messages, and may well be heretical) or we are standing on a very old lump of rock. Allegedly, 50 per cent of Americans believe that the Earth was created less than 10,000 years ago, which if true says something rather sad about the most expensive education system in the world.

America is fighting, all over again, a battle that was fought to a finish in Europe a century ago. The European outcome was a compromise: Pope Pius XII did accept the truth of evolution in an encyclical of 1950, but that wasn’t a total victory for science.2 In 1981 a successor, John Paul II, gently pointed out that ‘The Bible … does not wish to teach how the heavens were made, but how one goes to heaven.’ Science was vindicated, in that the theory of evolution was generally accepted, but religious people were free to interpret that process as God’s way of making living creatures. And it’s a very good way, as Darwin realised, so everyone can be happy and stop arguing. Creationists, in contrast, seem not to have appreciated that if they pin their religious beliefs to a 6000-year-old planet, they are doing themselves no favours and leaving themselves no real way out.

Darwin’s Watch is about a Victorian society that never happened – well, once the wizards interfered, it stopped having happened. It is not the society that creationists are still attempting to arrange, which would be far more ‘fundamentalist’, full of self-righteous people telling everyone else what to do and stifling any true creativity. The real Victorian era was a paradox: a society with a very strong but rather flexible religious base, where it was taken for granted that God existed, but which gave birth to a whole series of major intellectual revolutions that led, fairly directly, to today’s secular Western society. Let us not forget that even in the USA there is a constitutional separation of the state from the Church. (Strangely, the United Kingdom, which in practice is one of the most secular countries in the world – hardly anyone attends church, except for christenings, weddings, and funerals – has its own state religion, and a monarch who claims to be appointed by God. Unlike Discworld, Roundworld doesn’t have to make sense.) At any rate, the real Victorians were a God-fearing race, but their society encouraged mavericks like Darwin to think outside the loop, with far-reaching consequences.

The thread of clocks and watches runs right across the metaphorical landscape of science. Newton’s vision of a solar system running according to precise mathematical ‘laws’ is often referred to as a ‘clockwork universe’. It’s not a bad image, and the orrery – a model solar system, whose cogwheels make the tiny planets revolve in some semblance of reality – does look rather like a piece of clockwork. Clocks were among the most complicated machines of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and they were probably the most reliable. Even today, we say that something functions ‘like clockwork’; we have yet to amend this to ‘atomic accuracy’.

By the Victorian age, the epitome of reliable gadgetry had become the pocket-watch. Darwin’s ideas are intimately bound up with a watch, which again plays the metaphorical role of intricate mechanical perfection. The watch in question was introduced by the clergyman William Paley, who died three years after Darwin was born. It features in the opening paragraph of Paley’s great work Natural Theology, first published in 1802.3 The best way to gain a feeling for his line of thinking is to use his own words:

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain there forever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for anything I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case, as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, viz. that, when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point to the hour of the day; that if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner, or in any other order, than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all could have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it.

Paley goes on to elaborate the components of a watch, leading to the crux of his argument:

This mechanism being observed … the inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at sometime, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

There then follows a long series of numbered paragraphs, in which Paley qualifies his argument more carefully, extends it to cases where, for instance, some parts of the watch are missing, and dismisses several objections to his reasoning. The second chapter takes up the story by describing a hypothetical ‘watch’ that can produce copies of itself – a remarkable anticipation of the twentieth-century concept of a Von Neumann machine. There would still be good reason, Paley states, to infer the existence of a ‘contriver’; in fact, if anything, the effect would be to enhance one’s admiration for the contriver’s skill. Moreover, the intelligent observer

would reflect, that though the watch before him were, in some sense, the maker of the watch which was fabricated in the course of its