About the Book

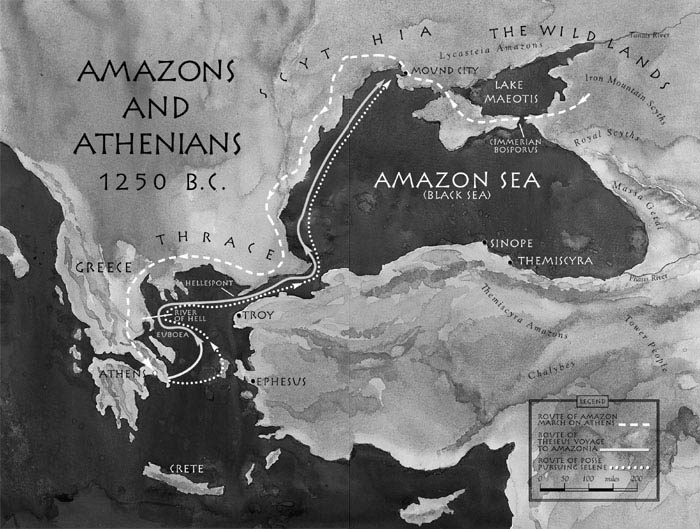

In or around 1250 BC, so Plutarch tells us, Theseus, king of Athens and slayer of the Minotaur, set sail on a journey that brought him to the land of tal Kyrte, the ‘Free People’, a nation of fiercely proud and passionate warrior women whom the Greeks called ‘Amazons’. Owing allegiance to no man, the Amazons distrusted these newcomers with their boastful talk of cities and civilization. And when their illustrious war queen Antiope fell in love with Theseus and fled to Athens with him, they were outraged. Raising a vast army, the Amazon tribes marched on Athens. History tells us they could not win, but for a brief and glorious moment the Amazons held the Attic world in thrall before vanishing into the immortal realms of myth and legend.

Echoing to the sound of brutal battles fought hand-to-hand and peopled with wonderfully realized flesh and blood characters, this moving tale of love and war, honour and revenge brings the ancient world to brilliant life as it recounts the extraordinary, near-forgotten story of the last of the Amazons…

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

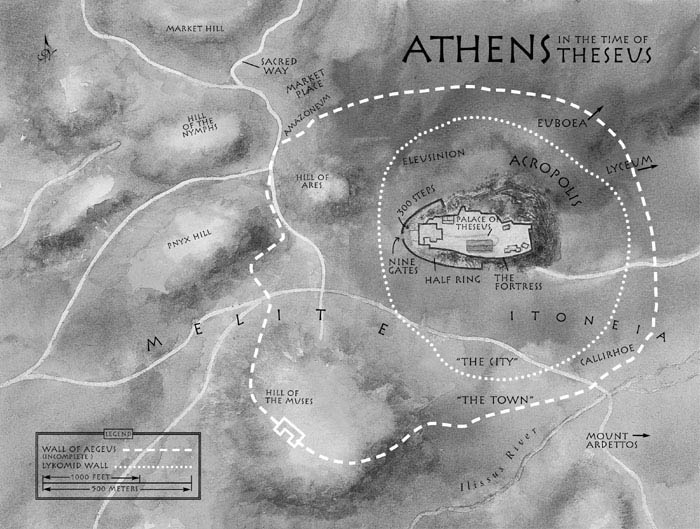

Maps

Book One: Mother Bones

Chapter One: A Tame Amazon

Chapter Two: Eleuthera Means Freedom

Chapter Three: Handsome Damon

Chapter Four: Daughters of the Horse

Book Two: The River of Hell

Chapter Five: Phalanxes of Iron

Chapter Six: A Transit to the Underworld

Chapter Seven: Europa

Book Three: Amazon Love

Chapter Eight: A Gathering of the Clans

Book Four: The Amazon Sea

Chapter Nine: The Silver Seed

Chapter Ten: The Birth of Democracy

Chapter Eleven: Beyond the Ken of God

Chapter Twelve: The Derangement of Eros

Chapter Thirteen: The Equestrian Square

Chapter Fourteen: A Duel of Honour

Chapter Fifteen: Reflections in God’s Mirror

Book Five: The Wild Lands

Chapter Sixteen: Our Sea

Chapter Seventeen: Massacre at the Parched Hills

Book Six: The Rape of Antiope

Chapter Eighteen: The Overthrow of Antiope

Chapter Nineteen: Across the Frontier of Love

Chapter Twenty: The Wiles of the Greeks

Chapter Twenty-One: Amazons and Allies

Book Seven: Athens

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Uses of Ecstasy

Chapter Twenty-Three: Starfish and Sea Horses

Book Eight: Sisters in Arms

Chapter Twenty-Four: An Army of Carpenters

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Musician’s Report

Chapter Twenty-Six: Nights and Days

Book Nine: Under Siege

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Toll of Victory

Chapter Twenty-Eight: A Trial of Aedor

Book Ten: In Love and War

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Rats

Chapter Thirty: At the Threshold of Victory

Chapter Thirty-One: The Watch Commander’s Tower

Book Eleven: The Battle

Chapter Thirty-Two: The Battle, Morning

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Arming of Antiope

Chapter Thirty-Four: Agony of Antiope

Book Twelve: Last of the Amazons

Chapter Thirty-Five: The House of Oaths

Chapter Thirty-Six: The Complicity of the Gods

Chapter Thirty-Seven: A New Order

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Princes of the Plains

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Spawn of the Darkness

Chapter Forty: An Amazon

Chapter Forty-One: The Iron and the Moon

Chapter Forty-Two: Eleuthera and Theseus

Chapter Forty-Three: Passengers

Chapter Forty-Four: An Act of Statesmanship

Chapter Forty-Five: A Rite of Remembrance

Chapter Forty-Six: Amazoneum

Author’s Notes

On the Historical Reality of the Amazons

A Note on Spelling

Special Thanks

About the Author

Also by Steven Pressfield

Copyright

For Lesley

Once before now I travelled to Phrygia where the vines grow, and there I saw a host of Phrygian men with their quick horses … I too was numbered among them on the day when the Amazons came, women the equal of men.

Priam, in Homer’s The Iliad

This was the origin of the Amazonian invasion of Athens, which would seem to have been no slight or womanish enterprise. For it is impossible that the Amazons should have placed their camp in the very city, and joined battle close by the Pnyx unless, having first conquered the country around about, they had thus with impunity advanced to the city. That they encamped there is certain, and may be confirmed by the names that the places thereabout yet retain, and the graves and monuments of those who fell in the battle … For indeed we are also told that [a number] of the Amazons [who] died were buried there in the place that is to this time called Amazoneum.

Plutarch, Life of Theseus

BOOK ONE

MOTHER BONES

ONE

A TAME AMAZON

WHEN I WAS a girl I had a nurse who was a tame Amazon. Of course such an expression is a misnomer, as one of that race may be domesticated no more than an eagle or a she-wolf. Selene however (this was her name, ‘Moon’) had been detached at the age of nine from her skyle – the words for ‘battalion’ and ‘family’ being the same in the Amazon tongue – and sent to dwell among civilized society, at Sinope on the Black Sea, and had thus become conversant with settlement ways. She could not endure such confinement however; at the age of twelve she stole a horse and weapons and fled home to the Wild Lands. As a grown warrior Selene fought at Thorn Hill against the Trojans and Dardanians, at Chalcedon against the Rhipaean Scyths, and at the Halys against the fifty sons of Admetus. She could speak Greek and served both as adjutant and envoy, as well as commanding in the hippotoxotai, the fabled Corps of Mounted Archers. She held the rank of wing captain in the Great Battle of Athens, in which Theseus and his allies of the Twelve States, after months of fighting, at last beat back the army of women.

Selene surrendered shield and bridle at the pass between Parnes and Cithaeron, where the graves of Amazons may still be seen, alongside her lover Eleuthera, ‘Freedom’, who bore numerous wounds, and to secure whose ransom and release Selene yielded up her own liberty. Selene was never shackled or stockaded in my father’s service, but held by her word alone, and so served honourably, governing my sister, Europa, and me until my sister’s fourteenth (and my eleventh) year.

You eldest of my daughters, reckon the bloodbath that transpired at that season. Each year I recount the tale on this eve of the festival of the Boedromia, beneath that horns-skyward crescent called by men an Amazon moon. None of male sex, father, brother, husband or son, may learn this chronicle now or ever, nor any fraction, so have we all sworn, even you youngest, donating our blood in the Iron Rite of Ares. Repeat with me now: who abjures this vow shall perish at our hands, so pledge we all.

Arise now, children. You youngest, take the hands of your sisters and follow me, Mother Bones, into the outer court. None will disturb us here. Double your overcloaks and set them in a ring upon the earth. The night is warm. Nestle at one another’s sides, resting your backs against the walls or trees. There. Let us form the Moon Crescent whose name is labrys, ‘double axe’, while I at its apex recite our lore. Listen well, daughters. Each verse I narrate, sear into memory. You eldest, who have heard the tale each autumn as you grew, accept this charge: if I alter so much as one stanza, bring me to book upon it, for our incantation wants naught of legend but truth alone. And when you come to impart this history to your own daughters, recall this commission and transmit these wonders uncorrupted, as I to you.

Selene feared the race of men. They exuded self-dignity, what she named anaedor, ‘no breath’ or ‘without soul’. She called Greeks ‘stick people’, by which she meant they creaked, stiff and wooden. Nor did she confine such reproach to men, but included Mother as well, and the women of our farm and of Attica entire, of whose behaviour Selene could make no sense and in the presence of whose everyday acts, as the haggling with vendors or the chastising of servants, she often lowered her gaze, a gesture I have seen repeated by others among the Amazons, whose notation is of embarrassment for the actor observed and the courtly wish not to compound this by making her conscious of a witness.

Selene feared this quality in men, this obliviousness. It was what permitted them to tread on a beetle and not hear its cry, or rend the sheath of the earth with a plough and not feel her anguish. Yet Selene and her race, as all savage nations, were capable of appalling cruelty. God help the man, or woman, who fell into their clutches when they defended their honour or painted their faces for war.

Amazons believe in hate. Hatred is sacred to Ate, to Hecate and Black Persephone, and to Ares as well, whom they call with the nymph Harmonia their progenitor. Ephesian Artemis, whom they worship, was the greatest hater ever, they claim, surnamed Void of Mercy, and even Harmonia, whose name means concord to civilized folk, means rancour in their tongue. Amazons believe that mothers hate daughters and daughters mothers, that sea hates sky, and night day. The world is held together by hate, which is in their lexicon a bounty and divine dispensation. Lovers must hate one another before they may love, and to this end the bonding ritual which Amazon novices perform at eight and twelve, when they formalize their trikonai, the notorious ‘bonds of three’, is constituted of a savage type of hand-to-hand brawling they call anitome, ‘any time anywhere’. Kicking, biting, eye gouging, all are sanctioned. The elders form a circle about the fighting girls, plying with horsewhips any combatant perceived as slack in her attack. Once over, the fight and its memory, the Amazons believe, form a bond which endures such that no warrior thus bound may ever desert another.

Selene cuffed Europa and me regularly. Nor were these love pats, but such blows as to fetch us off our feet. As frequently she caressed us, and many times must be scolded by Mother or Father for expressing affection at inappropriate moments, as in the presence of priests or elders. She slept in our beds, or we in hers, till we were six.

The shield and bridle that Selene had surrendered were objects of supreme fascination to my sister and me. Father did not display these as trophies, not wishing to dishonour Selene; in fact he sought more than once to return them. Selene would not take them. They came to be stored in a chest in the loft above Father and Mother’s room. Europa and I soon learned to pick the lock; we would mount to the attic and linger all afternoon, absorbed in the scent and sensation of these artefacts. We marvelled at the workmanship of the bridle, which was ox-hide rimmed with ivory and electrum, the right cheekpiece depicting a griffin taking down an elk, the left a crescent moon, and a snaffle bit of pure gold. Selene’s shield was of bearskin, from the densest pack across the shoulders, crescent-shaped and three layers thick, laminated with a glue of elk sinew and faced with the skin of a black leopard. On one’s arm it felt like a timbrel drum, taut in its ash frame, astonishingly strong for something so light.

Selene smelled. Mother would not permit her into the formal rooms of the house, as the odour she exhaled, so Mother claimed, clung to every garment, to her hair, and even to the walls themselves. ‘Can you not smell it, children? Good God, what a stink!’ Mother chased our governess, often with a broom, to peals of our laughter. For Selene’s part, she abhorred the house and entered it only under compulsion, as civilized folk will a tomb. She could not hear in a house. I recall Father, seeking to chastise her for some transgression, calling her before his big counting desk. ‘Why the devil won’t you listen, Selene?’ Her silence drove him wild. Finally he realized she could only hear him if he bespoke her out of doors. Soft worked better than hard. No blow or threat availed, nor gifts, however precious, to bend her counter to her will.

Selene permitted herself a solitary vanity: her hair, which was jet, of such luxuriance as to appear almost beyond human. She curried it as a horse’s mane, of which it reminded me, and dressed it, apart from men’s eyes, in the following manner. The top mass was first thrown forward from a part running ear to ear across the crown. The horsetail falling rearward was divided in four parts and cinched by four silver clasps, one for each cardinal direction. These were lifted off the neck and rolled together into a sort of broad horizontal bun, as gentlewomen of Cyrene do, which was then bound tight to the rear of the head by an ox-hide thong called xaella, ‘clothesline’, which itself is wrapped four turns about the head. The xaella is a weapon, a garrotte. Its ends are tipped in elk horn and etched with the battle-axe of Ares. Once the rear was set, the thrown-forward forepeak would be drawn back, half of its mass cinched at the crown, to form a horsetail with its excess, the remainder woven in among the four quarters. The effect of this, either loose or topped with the Phrygian cap of doeskin, was both glamorous and fear-evoking, as the mass of hair seemed at once to make its wearer half a head taller and, as well, provide a helmet of its own, to cushion a fall or blow. The worst thrashing Europa and I ever received from Mother came when she discovered us dressing our hair in this fashion.

It became Selene’s wont, each autumn round the anniversary of the Great Battle of Athens, to ‘borrow’ javelins and steed by night from Father’s stable and make away into the hills, holding fugitive for as long as a fortnight. At the first of these decampments, Father outfitted posses and published bounties for her recapture. Yet it became clear that no rider could overhaul her, or face her wrath if he did, but that Selene, left to her devices, would return of her own, sated by whatever trials or wonders she had undergone and content to serve out her sentence, so to say, for another twelvemonth. Never would our governess recount her adventures, despite Europa’s and my most piteous pleadings, save in the form of songs, whose verses appeared nonsense at first but later came to impart their cargo of wisdom.

These rideaways, as we called them on the farm, became if not condoned, then tolerated. My father came even to joke of them, enquiring of Selene when she planned to fly the coop this year, that he might draft his schedule around the date and hire on in advance a surrogate to supervise the children. Selene herself could not predict the hour of her absconding. She went when she went.

The bucks of the farm called Selene ‘Titless’ – what they in ignorance took A-mazos to mean – though never to her face. In fact the term Amazon derives from the Cimmerian Ooma Zyona, ‘Daughters of the Horse’. This was meant pejoratively. The Cimmerians (who only acquired horsemanship latterly) sought to offer insult to their rivals of the plains. The Amazons viewed this with contempt. They never use the word Amazon to describe themselves; Selene employed it only in converse with Greeks and then grudgingly, because it had gained currency. Likewise she transposed Amazon names into Greek, as Alcippe, ‘Powerful Mare’, or Melanippe, ‘Black Mare’.

They lusted after Selene, the swains of the farm, as they did all the maids, nor was Selene averse to grappling with him she favoured, yet none could temper her or draw an uncoerced smile. Only beneath music’s spell would she relent, the proper tune proffered by the proper suitor, and then only with such a sorrowful and distant measure as to render her yet more remote.

There had been others of Selene’s kind in Attica then, taken like her of wounds after the Great Battle. Several had been made mistresses; others placed in service. All ran off. Chained or bound, they died. Only Selene, constrained by her pledge and her care for my sister and me, abided. She acquired notoriety. Town people would contrive occasion to visit the farm, nosing about to observe one of that race called in the Scythian tongue oiorpata, ‘man killers’. ‘Has her right breast indeed been seared off, to better draw the bow?’ ‘Do you permit her near weapons?’ ‘What holds her from running?’

Once a dame of the district of Melite, the aunt of Prince Atticus, to whom my sister would become betrothed, upbraided my father for exposing his daughters to such unholy influence. ‘The children will grow to be savages! Who will teach them to card and spin? How will they learn to hold seemly silence?’

My father believed girls should ride and run, not grow effeminate, squeamish to take game or trek alone in the dark. Who better to impart such arts than a wing captain of Amazonia? Father admired Selene. He wore his custody of her with a covert pride, as one might holding the leash on a she-bear or a lioness. He felt protective of her. For men hated Selene on sight, and women more so, which phenomenon never failed to both stir and alarm my sister and me, and in the presence of which both of us were struck with a rage we could neither name nor exonerate.

Theseus himself, lord of Athens, owned acquaintance of Selene and had despatched communications to her on occasion, including gifts which she disdained and, to our awe, discarded. On a spring noon in my eleventh year the king travelled out specifically to speak to her. Never had there been such a day! Here down our lane advanced Theseus, monarch of Athens and Eleusis, master of Crete and the islands; he who had brought the dominion of law to Attica, binding within one polity the fractious barons and purging the land, in Myrinus’ phrase, of the brigands of misrule.

Theseus was our father’s kinsman, the king’s mother Aethra and Father’s mother Polycaste being cousins, and both Father and his brother Damon had accompanied Theseus a generation earlier on his first voyage to the Amazon Sea; yet never in memory had he trod the stones of our estate. He arrived by carriage, not horse or foot, for he had broken a bone in his thigh some days before and must limp about by means of a forked staff. Ah, yet, when he came! Who had beheld a handsomer man! Taller by half a head than my father, himself tallest of the district, and carved as from oak. The pelt of his forearms, burnished gold from the sun, made me shiver, and his curls falling to his shoulders bore such a sheen as put one in mind of wild harts and martens. It took slender imagination to understand how Antiope, the Amazon queen, could have fallen so beneath his spell as to desert her own kind and even do battle against them, at this monarch’s side.

My sister and I scrutinized great Theseus’ apparel: a simple white tunic with a blue border and a rust-coloured overcloak, clamped with a brooch of gold in the shape of a sponge. Here was the story:

Once during Theseus’ early tenure as king, a commoner had approached the palace seeking a hearing. He was informed that our lord was at his bath; entry was permitted to no-one. But the king heard the man at the gate and motioned his guardsmen to relent. He received the fellow while still in the tub and rendered his judgment, which happened to be favourable. When the nobles learned of this they were outraged by its want of dignity. But the gesture endeared Theseus to the commons, so that to this day to act ‘from the bathtub’ means to bypass channels and move immediately with compassion. In gratitude the petitioner presented Theseus with a golden charm in the shape of a sponge, which the king prized beyond all other honours and set in place on his garment, men said, before even his brooches of royalty.

So too did he act on this visit to our home, saluting Father as ‘Elias, dear cousin and friend’, and Uncle Damon as ‘my fellow black sheep’. He disburdened himself of all signia of rank, surrendering these to my sister and mother as a mark of respect to them, and when he sat apart with Selene beneath the oak (which ever after came to be called the King’s Oak) it was a sight of wonder to those of the farm, above all the hands who despised her, to behold with what deference the king bespoke the captive maid and with what grave attention he received her response.

We could not know of that which he informed Selene, namely, the critical wounding in battle of her lover Eleuthera, three months’ trek east in her homeland on the Black Sea. The report, months old, had only the day before reached Athens by ship, and Theseus, honouring ancient oaths, had felt bound to impart it to Selene in person. Amazons may only take lovers in threes, the triple bond they call trikona. Hell, they say, will take any one of the three in place of any other. This is the stem of valour in battle, the Amazons believe, for each triple-mate may donate her life to preserve her comrade’s. Selene and Eleuthera were such mates. Nor could one tell by studying Selene’s face what grief or resolve she formulated on that account, by so little did her aspect alter. Only later that evening, tracking her like spies, did my sister and I discover the charm of flint and horn she had hung upon the camphor tree which stood alone upon the farm’s east-facing slope. This the Amazons call an aestival, which term has no equivalent in Greek. It is like a ticket one leaves for a friend to attend a chorus or dance. An aestival is a pledge to set one’s own life in place of her lover’s and, failing that, signalizing the vow to reunite with her in hell.

Theseus well comprehended these savage tenets and tendered warning to my father, speaking apart in the aftercourse of his interview with Selene, that she, driven now by a mandate superseding that pledge which held her in indenture, might claim her release or even seize it by her own hand. Father understood this as well. Both men were aware of the imperative held by all warrior races to serve honour before survival. This too might impel Selene to run.

We children divined this as well and more, intimates of our governess. We knew the romance which bound our king to the Amazon Antiope, who had fought at his side in the Great Battle. Perhaps the king yet loved Antiope, long perished as she was, or feared the magic of Eleuthera, who bore the war name of the Scythians, Molpadia, ‘Death Song’. Our girls’ eyes never left the monarch, seeking in his demeanour some hint of heart-soreness, which we thought we detected, unaware of its actual source. Nor did the youths of the farm, restrained by their own diffidence from approaching, dare bespeak the king in such frank manner as the governess. We could see them mutter to one another as men will. ‘What’s she got, that wild bitch, that sets her so high and mighty over us?’

They hated Selene before, and more now, so that this night, after the king’s party had departed, the bucks came for Selene in her kennel, a bark lean-to alongside the room I shared with my sister, and dragged her forth to the dark. When Europa and I made to scream, Selene fixed us with a glare that commanded our silence, which she herself would maintain, we knew, and bear mute all the men would do, though we flew anyway to Father and Mother, but neither would come at once, though we implored them, knowing the ravagement of person being inflicted on Selene with each moment’s delay. Father believed that on the farm, as on a ship, the hands sometimes may not be ruled but must work out their malice, and him or her judged most outcast must bear the toll. I hated my father in that hour. Perhaps he too feared Selene’s flight yet knew not how to quell it, or felt his mastery of her failing or proving false. He departed to her rescue indeed, but absent haste.

Mother held Europa and me from following, and, tugging us to her breast, made to account. ‘Selene is not a person as you or I, children, but a wild creature who may bear that which to a human being would be intolerable.’

‘Do you mean she may be violated, as drakes in a gang assault a duck?’ This my sister demanded and received a blow for her insolence.

Mother restrained us long enough for the men to work their evil: then, Father reappearing, with a look released us. We understood we might tend Selene now, and flew to her.

Men gave it out that what came later was revenge for the way she was shamed, or grief at the news she had borne. It was neither. For one of her race, who had surrendered and served, no further shame was possible, nor was grief grounds for vengeance but only altare, union with the fallen, as the Amazons call it in their tongue.

Selene did not run away that night. Rather she called Europa and me apart, to that plane copse where she had schooled us in silence, and over three nights imparted to us her history. When an Amazon senses the hour of her death approaching – when wounded or ill, say, or on the eve of some battle before which she has received a vision or sign of her impending end – the law of her race commands her to ‘make her testament’. She gathers her daughters and imparts her chronicle. Such account, Selene conveyed to us, rarely takes form as a narration of events, but may contain as much of visions and dreams as of waking adventure.

These annals Selene now delivered to us, as I this night pass them on to you. She told of her childhood upon the eastern steppe; of the arrival by sea of Theseus twenty years past; how the king had won the heart of Antiope, war queen of Amazonia, and fled with her to Athens. Selene told of the fury of the Amazons and of the marshalling, beneath Eleuthera, of their own clans, reinforced by the male tribes of the plains, Scyths and Maeotians, Thracians and Tower People, Massa Getai and Thyssa Getai, and fifty other nations, and of this army’s three-month trek west and assault upon our city. These wonders Selene narrated with such unwonted urgency as to strike my sister and me with dread (for why would she offer her testament unless she was preparing to die?) yet we were bound to silence by our love for her and the awe in which we held her.

On the third night she led us apart to that toppled wall we children called the Viper’s Pocket and there, inserting her arm to the shoulder within a cleft, felt about and withdrew a stone adder, the serpent yet torpid with the night chill, whose poison the Amazons employ to produce that state called in their tongue adraneia, ‘no turning back’. Clamping the snake behind the neck, Selene set its nostrils adjacent her calf. She uttered no cry, nor moved, as the fangs entered her flesh and she struck off the head with her sickle. Her blade prised apart the snake’s jaws and extracted the fangs, deep as the joint of a thumb. She sang:

Kallos beauty, orge wrath,

Heart speaks but none listen

Save we on this path.

Now look you there, daughters and granddaughters, beneath the moon, to that drystone wall which yokes the shearing pens to the gate of the lane.

From there, on the noon succeeding that night, Selene came mounted on my father’s stallion, which she had stolen from its stall moments before. Between the steed’s jaws set the golden bit of Selene’s bridle; on her forearm rode the war shield of bearskin and black leopard. She whipped the beast to the gallop, while the boys and men of the farm raced in a gang to cut her off.

Scyllus the goatherd Selene drove through with the flung javelin, there before the wall, striking him in the solar plexus with the full force of her throw, enlarged by the horse’s rising moment so that the herdsman did not even stagger but was nailed, as a plank beneath the joiner’s mawl, against the boards of the gate, slain before his mouth could gape or arm ascend to direct the alarm.

With the bow Selene slew Dracon the foreman, there beside the spring’s hollow, and at a gallop leapt the wall, loosing a second shaft as she flew, which took the boy Memnon square in the throat, slicing the voice box through and severing the column which supports the weight of the skull, so that he dropped like a sack of stones, life-fled before his carcass hit the dirt. And here Mentor, called Top Hand, who had abused Selene most brutally and handled her most with contempt, seeing her vault wall and palisade and bear down hard upon him, wheeled to flee.

Now from the Amazon’s throat, which had endured so long in mute forbearance, ascended that war cry which even to recall at the remove of years sends the gooseflesh coursing, and, snatching the woodsman’s hatchet she bore in the stead of a battle-axe in the brace across her shoulders, she slung this weapon upon her fleeing prey at a dead run, its warhead whistling end over end to fix him between the shoulder blades and plunge a full hand’s breadth deep into sinew and bone. The force of the blow drove the brute face-foremost into the dirt, where he struck and bounced, arms neither flung wide in agony nor extended before him to break the fall but hanging slack at his sides, and slid upon his chest as a stone skipped across a pond, to skid crown-first into the wattle underpan of the sows’ trough, dead as a rat and as void of locomotion.

Selene’s mount’s hooves thundered past and, strewing straw as she heeled him hard over, slewed round the corner and raced away up the slope, trampling the grafted vines which had been staked out just that forenoon. She vanished beneath the olives of the rise, leaving naught but hoof-punched dust to drift and settle, punctuating her flight.

TWO

ELEUTHERA MEANS FREEDOM

TWO NIGHTS LATER I woke to find my sister gone. I knew at once she had fled to follow Selene. The transom beneath the eaves was our accustomed escape (as our little room had no window and no outer door); in moments I was up and over, barefoot, and away into the woods.

There must have been fifty hiding places employed by Europa and me, to any of which she could have flown, yet my feet bore me towards that plane grove, our academy of silence, where Selene sacrificed a dove to the moon at each solstice. Once in winter when I had stamped there with the cold, our governess had made Europa and me (for one may not be scourged apart from the other) stand nightlong in frost so hard we lost sensation to the waist. I crested the slope now, lungs heaving, only to have a blow unseen cut my feet from beneath me. I plunged, on my back in my nightshirt, to discover a form upon my chest and a blade at my throat.

‘Who has followed you?’

It was Europa. She was naked. Dark as it was, I could see three slashes carved in echelon into the flesh of her breast. This was the matrikon, the ritual self-mutilation practised by the Amazons on the eve of battle.

‘What have you done to yourself ?’ I cried.

My sister’s horse Redhead waited, laden with kit.

‘You mean to track Selene!’

Europa hissed me silent. ‘Why did you follow, Bones?’ (This is the name I was called as a child, for the dearth of meat on my frame.)

‘Take me with you!’ I begged.

Europa had mounted to the crown of the slope and held there, motionless, listening. At last satisfied that no-one had tracked me, she skidded down and again seized me by the wrist. ‘There, feel it?’

She thrust my hand between her legs.

‘I bleed woman’s blood.’

The hair stood erect over all my body. My sister’s first moon flow. She was a woman now. I could see from the churned earth that she had been dancing. She turned from me in a state of exaltation and elevated both arms towards the moon, which was her namesake, Europa ‘Broad Face’, as it was Selene’s ‘Full Moon’. Her breath steamed upon the air. I marvelled to behold her in this transport, impaled in ecstasy upon that shaft which lanced silver between the trees.

‘Take me with you, sister!’

‘You must keep this secret. You heard the men today!’

Indeed at dawn this day Europa and I had trekked into the city to the site of the Assembly and there watched from the peuke copse at the brow of the Pnyx (along with other children, slaves, and women debarred by law from deliberations of policy) as the men debated Selene’s fate and what action to take regarding her crime and flight.

Outrage had been fierce and immediate in the wake of the farmyard massacre. Before the blood of the slain had dried, their male kin had been sent for, while the dames swarmed about their slaughtered sons and husbands, wailing in woe and horror. Bring horses and weapons! Muster a posse! Father was appointed captain. My sister and I could see him stall. As an hour slipped away, and another, in the marshalling and provisioning and assigning of arms, the zeal for pursuit abated. Common sense told the futility of launching after Selene. Who could overhaul the Amazon, who had the postnoon’s start and gained more with each hour? Selene would run her mount till it dropped, then steal another and another, while the company on her trail must trade for or purchase fresh animals, through a country already made disgruntled by its prey’s passage; nor could an armed party pass through alien states absent permission of their princes. Theseus himself did not wish to make a case of this, when his ministers informed him of it later that day, reckoning other affairs of state of far more pressing urgency, namely the increasing boldness of certain barons, agitating for independence from the crown, not to say their allies in the Assembly, who sensed, perhaps, a slackening in Theseus’ support among the people and sought to exploit this for their own advantage.

The day passed, and another. Rage at Selene moderated, succeeded by grief for the slain and a darker sense, never absent among superstitious country folk, of a god’s hand in the play. Perhaps heaven had willed this holocaust. Surely the dead could make no claim to blamelessness. And their kin, however passionately they may have wished for revenge, were poor men with few resources and less influence.

And so all sought to put from mind this unhappy episode, the running-amok of an obscure and doubtless half-mad governess. But one man, Lykos, the son of Pandion, who was brother to Theseus’ father Aegeus and felt himself cheated of Athens’s throne, hated Theseus and bore him malice for this and other ills long past. Lykos perceived in the event of Selene’s crime and flight the chance to work evil to his enemy. So he set himself to inflame the people, declaring in assembly that such lawlessness unpunished would inspire further mischief – not the harmless outlawry of boys or men but that of women, most pernicious and foul. This struck a chord. For what husband or householder – Lykos incited the males of the Assembly – may close both eyes in sleep when tame governesses sling fatal darts and fly unscourged to alien lands?

The orator recalled to his hearers that epoch, so few generations past, when fathers could not even name their own sons with certainty, such was the promiscuity of women. Here at Athens our king Cecrops had founded the institution of marriage, by which the unchaste nature of the female was at last governed and the rights of property accession, father to son, established in accordance with heaven’s will.

‘How scandalous, men of Athens, if our city, where God first bound female to male in holy matrimony, should be the site of this ordinance’s overthrow. Here too did divine Demeter first tutor man in bringing forth the bounties of the earth. To our fathers she taught cultivation of the soil and husbandry of animals, by which arts, shared by us freely with all humankind, has the race of men elevated itself from the slough. Here our fathers founded the twin pillars of civilization – agriculture and monogamy. Will we, their sons, permit both to perish? Let this wild woman get away with murder,’ Lykos railed, ‘and we might as well strike the city and return with her to cleft and mire!’

The Assembly met then as now outdoors on the hill of the Pnyx, presided over by Theseus, and from this vantage Lykos gestured to the quarters south, west, and north, recalling to his countrymen the siege of the state, only one generation past.

‘Have you forgotten so soon, men of Athens? Let me remind you, then, of that hour when the hordes of Amazonia made their camp on the very stones upon which we convene today and kindled for their cookfires the timbers of our homes, which they and their savage allies had razed entire, driving us before their host in terror. Nor did the ranks of the foe stand slender or attenuated, but in depth twenty shields, with battalions of male auxiliaries, wild Scythians and Thracians and Issedonians, Black Cloaks and Tower People, Massa Getai and Thyssa Getai, painted Tralliai and screw-maned Strymonians, archers and slingers as well as armoured infantry, and cavalry above thirty thousand. Nor could we repair to our estates, gentlemen, for the army of Amazons had captured all, laying waste the countryside from Eleusis to Acharnae, while we ourselves starved and rationed water, huddled on the Acropolis behind a palisade of timber and stone. Have you disremembered, men of Athens? Has this little scrape escaped your recall?’

Lykos called on Theseus to mount a pursuit of the Amazon Selene by fleet and army. He so agitated the people that they stood upon the instant of approving a motion to pursue the fugitive all the way to the Black Sea if necessary, exacting vengeance not on her alone but on whatever remained of her race, wiping them out at last and for all time.

Our king rose upon his hobbled leg. The herald set the speaker’s skeptron in his hand.

‘Men of Athens,’ Theseus began, ‘I stand in awe of this demonstration of spirit. Would that the commonwealth could call upon such zeal in all her perils. Yet you will acquit me, I hope, if I detect within our speaker’s fervour a subtler and more duplicitous scheme. What do you care for this issue, Lykos? I dare say you would not part with a parsnip for the sake of this female Selene or the victims of her wrath, none of whom you could even name before yesterday.’ The king indicated his president’s throne. ‘You’d like this seat, wouldn’t you, Lykos? Or failing that, the satisfaction of ousting me from it? Lykos! Your name means Wolf and like a wolf you stalk me.’

Murmurs greeted this, and cries from both parties.

‘What I shall do about this wild woman,’ Theseus resumed, ‘I know not yet. But I know what I will not do. I will not pursue her across oceans. Not from fear of rivals, however skilled in their manipulation of their countrymen’s passions, but because it is simply not worth it. I will not elevate the moment of this lamentable murder by my participation in the pursuit of its instrument.’

Theseus set forth an alternative. If Lykos craved so fervently the capture of this savage maid, let him lead the party in person. The state would foot the bill, declared Theseus, and he himself would donate twenty battle mounts, trained and tractable for sea transport. ‘Name your ships and men, Lykos, and I will fund them. If you return with your prize, may all glory redound to you.’

It was with no slender amusement that Europa and I, not to say the Assembly entire, played witness to Lykos’ recitation of alibis to duck this chore. He retreated beneath a storm of derision. The Assembly adjourned.

Now at midnight in the plane grove, my sister dressed and drew her riding cloak about her; she took Redhead’s reins and moved to mount. ‘Do you remember Selene’s testament?’ she asked me.

Of course I did. I could recite it by heart.

‘And her story of Eleuthera’s warrior oath?’

Of course.

‘If Eleuthera lies now near death in the Amazon homeland,’ my sister said, ‘and Selene has flown to aid her, then I must go too. To preserve her if I can! I would gladly die beside her, or for her.’

None but a younger sister knows the thraldom in which she stands to her elder. It rubbed even harder with Europa, for she was such a prodigy as rider and runner, fastest of our district, boys included, and possessed of the wildest heart and keenest wit. Now she was a woman, set to launch upon the most brilliant of adventures, while I, her mealy brat sister, must not only wither at home, bereft of her and Selene, but act out the pretence of ignorance to all who would quiz me later. I feared too for my dear sister. She was just a girl! I loved and hated and envied her all in the same breath.

Europa saw it. She drew me to her. ‘You must second me now, Bones, as Selene seconded Eleuthera. Do you remember the story?’

Indeed. Selene had told it a hundred times; we begged for it, my sister and I, never tiring of its recitation.

Selene’s elder mate of the triple bond called trikona was that Eleuthera whose life she had preserved by the sacrifice of her own liberty in the aftermath of the Great Battle of Athens. At the time of this childhood chronicle however (the one my sister referred to), Eleuthera was fourteen, Selene eleven – the same ages Europa and I were now – in the homeland of the Lycasteian Amazons, on the Wild Lands north of the Black Sea. Amazons may not renounce their virginity until they have taken the lives of three foes in battle. At that time Eleuthera had claimed one and bore his scalp on a rawhide thong at her waist. This night of which Selene spoke, a raid had been made by 200, Eleuthera’s clan and others, upon a party of Phrygian freebooters encroaching on their country. Eleuthera, emerging from the fray at a hard gallop to that defile where Selene and the other novices too young to fight waited holding the second string of horses, had skittered across the plain (it was winter, the earth iron-hard) calling to her younger mate to vault and ride; victory was theirs and no pursuit. Mount and follow me!

Selene had sprung to the back of Eleuthera’s two-horse, whom she had just finished ‘running off’ to get him his second wind, and heeling him with all her strength had barely held her elder in sight, with such joy did Eleuthera’s primary mount, a big long-legged gelding called Soup Bones, bear her across the frost. At last reining in, Eleuthera had permitted Selene to draw alongside and, stretching her lance moonward, held out upon its shaft two scalps of men, slick with blood and the still-steaming flesh of the crowns from which they had been torn. Eleuthera here howled such a cry of joy, Selene told my sister and me, as made the down of her arms stand up stiff as boar’s bristles.

‘Now by the laws I may take a man between my thighs,’ Eleuthera had cried, laughing. ‘But I shall not. Never! But make these my children’ – she elevated the scalps – ‘and by them, and all that follow, preserve the free people!’

This was Eleuthera’s warrior oath. My sister had imbibed the tale a hundred times, for she would beg to hear it, untiring, and Selene never denied her. I devoured it too, wondering at the manner by which our governess imparted it, ever the same, so that we came, Europa and I, to recite entire passages. My sister’s soul drank the song as a horse hard-ridden sucks water from a forest pool, and Selene, perceiving and approving, enlisted her whole heart in consummating our conspiracy. She drew Europa to her, and me, inflecting the tale with her touch as well. As she told of Eleuthera’s horse, we felt her knees press our flanks; her fingers played across our shoulders as hoof strikes on the steppe; she kissed us and flattened our breasts against hers so that the smell of her hair and the heat of her flesh reinforced the tale and became indivisible from it. She became Eleuthera to us, and as she, Selene, had surrendered in love to that warrior maid whose name means Freedom, so Europa and I fell in love with her.

I begged my sister to take me with her.

‘Of course you cannot go, Bones. But you may aid me if you will.’

I would! Just tell me how.

‘Buy time for me. Conceal my flight. Play the warrior when they grill you. Offer nothing. Back me as Selene has backed Eleuthera.’

I knew she was duping me. I could tell as she took my shoulders in her hands and bent her gaze to mine in savage confidentiality. She was ceding me a spy’s errand and passing it off as a hero’s. Yet she was my sister, my champion and mentor and ideal. What option did I own but to obey her, and make my peace with being left behind?

THREE

HANDSOME DAMON

EUROPA’S FLIGHT SET the city on its ear. Within hours ships had been secured and provisioned, men recruited and officers assigned. The running-amok of a captive governess was one thing; but that a respectable maiden of good house (and one who, when she reached fifteen, would be betrothed to Prince Atticus, son of the illustrious Lykos) could be so seduced from her wits as to make off in the train of such a savage, this set the public cauldron to the boil. Whose daughter was next? Whose sister, whose wife?

Censure for Europa’s flight fell upon Father, who was denounced not only for not placing a sturdier watch upon the maid (he should have known she would fly!) but for appointing a wild wench over his daughters in the first place. As for me, I came under as fierce an assault as my sire, for our offence was viewed not as a clan or tribal matter but as a crime against the state, to wit, inciting an insurrection of her women. Ministers of Lykos and others came to the farm and interrogated me under oath.

Where had Selene fled?

I did not know.

Where did I think she had flown?

I could not guess.

I was arrested. Armed men tore me from my mother’s skirts and bore me in a waggon into the city, where I was placed under detention at the town home of the baron Peteos, a hero of the war with the Amazons and father of Menestheus, who would one day rule the state. Such sequestration, I was informed, was for my own protection. I scorned this, until the first stones began crashing against the shutter boards.

Mother had been permitted to bring my clothes and weaving. But she too had come under suspicion. Before darkness had fallen that night, a mob surrounded the house and was only dispersed by the king’s guard hastening from the palace. Nor was this corps of vigilantes constituted of men and boys, as one might expect, but women, even respectable matrons known to Mother, not to say girls my own age, some of whom had been my playmates. How they howled for our blood!

Now it is a fact that in a crisis of lawlessness, one often discovers discharge not in the law but in the outlaw. Thus it ensued that Father’s brother Damon, the rogue of the family, materialized as our deliverer.

Damon was our handsome uncle, seven years Father’s junior, who doted upon my sister and me, as happens frequently with bachelor kinsmen possessing no issue of their own. Damon had farmed our estate with Father up until the Great Battle with the Amazons, in which he had fought against the army of women, at first with distinction, then later, apparently, with no small notoriety. He had taken their side, at least for an interval. Athens had set a price upon his head in that season; we children could never ascertain the particulars, for as soon as one of our elders commenced to speak of the occasion, a general clearing of throats would ensue and all sprats be banished from the room.

At any event, Damon had had to decamp from the bolt hole, as the bailiffs say, making his living thereafter by piracy and the hunt. It was he, when my sister and I were small, who made us to understand Selene’s shame at capture.

‘You must remember, girls, that Selene in her own eyes has committed the supreme sacrilege of her race, that is, to deny to her lover Eleuthera, whose soul stood in her care due to the gravity of her wounds, the boon of a glorious death. No panel has convicted Selene; only the heart within her bosom, by which she stands self-indicted and self-condemned.’

Uncle had always favoured Selene. He brought her cheeses and rare fruits from his travels; she would accept from him what she would from no other. I never saw them speak. Rather, each would take station across the court from the other, at such time as other business was being transacted and other traffickers filled the lane, so that a glance might pass between them, unremarked by strangers, yet freighted with volumes comprehensible to themselves alone.

Had Uncle been Selene’s lover? He was so dashing, and she so comely, that our lasses’ hearts must conjure aye. Yet never, for all our snooping, could Europa and I catch them at so much as the exchange of a word.

‘Among warrior races, pride is all,’ Uncle made us to understand. He told us of the flint daggers the wild tribes carry and of the rite of autoktonia, double suicide. ‘This is the act Selene was charged by the code of her race to perform when her mate Eleuthera’s wounds, and her own, made capture inevitable. I was there when we took her surrender, on the mountain track between Parnes and Cithaeron. Both women’s horses had been killed days past; Selene had borne her lover, near death, seeking to mount the pass at Oinoe. Each time the hill bandits of the district had spied them out, wounding Selene further, twice nearly capturing both. Some dozen of these villains had her birdlimed inside a shepherd’s hut when our patrol chanced upon them.

‘We drew up in wonder to behold this warrior, despite her injuries a specimen of peerless pride and beauty, arise from her covert and advance towards us, bearing her lover’s unconscious form in her arms, with her own hands weaponless and extended. To take an Amazon alive was a prize unheard of, and promised such distinction that our captain, moved as well by motives of clemency, granted her appeal – to reprieve the one and enslave the other.’

That had been seventeen years ago, six years before my birth and three before my sister’s.