Foreword

Author’s Note

Introduction: Into the Deep

Chapter 1 Beginnings

Chapter 2 “Sub Marine Explorers”: Would-be Warriors

Chapter 3 Uncivil Warriors

Chapter 4 Missing Links

Chapter 5 Later 19th Century Submarines

Chapter 6 Transition to a New Century

Chapter 7 Early 20th Century Submariness

Chapter 8 World War I

Chapter 9 Submarines Between the Wars

Chapter 10 World War II: the Success of the Submarine

Chapter 11 Postwar Innovations: the Rise of Atomic Power

Chapter 12 The Ultimate Deterrent: the Role of the Submarine in the Modern Era

Chapter 13 Memorializing the Submarine

Notes

Sources & Select Bibliography

From the beginning of recorded history the inhabitants of the earth have had a great fascination with what exists under the waters of lakes, rivers, and the vast seas. They also have maintained a great fear of the unknown and very few wished to actually go under the surface. In the not too distant past, they had a morbid fear and were deeply frightened of what they might find. Only three out of one hundred old-time sailors could swim because they had no love of water.

Yet the concept of the submarine and its protection from creatures of the deep began to emerge, and as such, began to be designed and built. Few were successful and took their creators to the bottom and never returned, but as it evolved, the submarine revolutionized naval warfare and waged brutal battles beneath the waves that sent hundreds of thousands of men to an early death.

James Delgado, a distinguished pioneer of sea history, prolific writer, and author of over 20 books on ships and sea, and one of the world’s foremost marine archaeologists, takes us through a fascinating history of the submarine; from David Bushnell’s Turtle that made the first underwater war mission in 1776 to the Confederate submarine Hunley that became the first submarine to sink a warship, through the notorious German U-boat battles to the huge nuclear-powered behemoths and the deep sea submersibles that explore the abyss.

Revealed in fascinating detail, Silent Killers creates a truly engrossing chronicle of the intriguing world of undersea vehicles.

The premise and promise of the submarine as a means to reach Earth’s last frontier, the depths of the ocean, has grasped public attention for hundreds of years, and in the last century the potential of the submarine as an instrument of war has increasingly commanded the attention of military minds. From hand-cranks, steam, electrical batteries and diesel to nuclear power, and from hand-set explosive charges to nuclear missiles, the submarine and the armaments it can deploy have made it the world’s ultimate naval weapon. The earliest wooden submarines have given rise to modern, titanium-hulled, fast, deep-diving, and stealthy “silent killers” that can strike from anywhere in the world where there is deep water – even through thick Arctic ice.

As an archaeologist with an interest in the role of technology in shaping society, I have long been fascinated by the development of the submarine. That interest has been honed by incredible experiences and opportunities to work with submarines. This has included archaeological and historical research into the Type A Japanese Midget submarines of the 1930s and 1940s and the detailed analysis of a misidentified Japanese submarine in the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia (US), said to be a sponge-diving craft but actually one of Japan’s top secret prewar prototypes for its Midget submarine force.

Following these earlier projects, I was later privileged to lead the effort to document and study the 1865 Sub Marine Explorer after encountering this forgotten and anonymous submarine wreck off Panama’s Pacific coast. I was also able to lead, while director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum in Canada, the reassembly and restoration of Jacques Piccard’s famous PX-15, Ben Franklin – something that meant a great deal of physical labor on my part and that of the staff and volunteers, scraping, bolting, and rigging heavy machinery to be lifted by a crane. Which meant really getting to know the sub. Other submarine archaeological adventures and projects have included diving on the atomic-bombed submarine Pilotfish at Bikini Atoll, site of the 1946 naval nuclear tests, and participating in three National Geographic projects to dive on and film the lost submarines U-21 in the North Sea and U-215 off Roberts Banks in the North Atlantic as well as the archaeological identification of the British submarine L-26 off the coast of Nova Scotia.

During my tenure with the US National Park Service, and as head of the US Government’s national historic maritime preservation program, I had occasion to learn more about many of America’s historic submarines in depth – if you will pardon the pun – with many detailed tours of one of the Nishimura prototype midgets, as well as HA-19, U-505, USS Bowfin, USS Cavalla, USS Pampanito, USS Lionfish, USS Albacore, USS Becuna, USS Clamagore, USS Cobia, USS Croaker, USS Drum, USS Torsk, USS Requin, USS Nautilus, and USS Silversides. In this capacity, I also personally conducted the US National Historic Landmark studies for HA-19 and USS Clamagore. Since my Government days, my interest in submarines has extended to other tours (including some where I was very kindly given interior access) of museum-displayed craft in the US and abroad, including those of HA-14 and HA-21 and HMAS Onslow in Canberra and Sydney, Australia, HMS Alliance and Holland No. 1 in Gosport, UK, Vesikko in Helsinki, Finland, Peral in Cartagena, Spain, Fenian Ram and Intelligent Whale in Paterson and Sea Girt, New Jersey, USS Blueback in Portland, Oregon, and RV Deep Quest and Trieste II in Keyport, Washington. I have also had great tours of the submersible Nautile at IFREMER in Toulon, France, rode in Mir 2 to the bottom of the Atlantic, 2½ miles down, and attended submarine flight school to drive (or fly) the new Super Aviator submersible. Obviously, submarines are more than an interest – they are a passion. As an archaeologist, historian, and writer, I know first-hand from these experiences, as well as research in the archives, how the submarine has changed warfare and humanity’s ability to reach all parts of the planet.

A number of colleagues and institutions have provided information, advice, reviews, and support through the years. I would like to thank the late Russ Booth, a dear friend whose passion for USS Pampanito was infectious, as well as Clive Cussler, Warren F. Lasch, Pete Capelotti, Mark K. Ragan, Michael “Mack” McCarthy, Captain Alfred S. McLaren, Ph.D USN (ret.), P. H. Nargeolet, David Jenkins, David Baumer, the late Toshiharu Konada of the Kaiten corps, Mike Mair, Gene Carl Feldman, Donald Kazimir, Selçuk Kolay, Oguz Aydemir, Savas Karakas, the late Jacques Piccard, Daniel Lenihan, Larry Murphy, Kevin Foster, Dave Conlin, Hank Silka, Bob Mealings, Eugene B. Canfield, Rich Wills, Lisa Bower, Clyde Paul Smith, John B. Davis, Mike Fletcher, Warren Fletcher, Bob Neyland, Chris Amer, Maria Jacobsen, Paul Mardikian, John McKee, Bob Schwemmer, Doug DeVine, Carlos Velasquez, Todd Croteau, John Wagner, Joe Hoyt, and John McKay.

The following organizations and institutions were also a great help: the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney; the Estonian Maritime Museum, Tallinn; the Rahmi M. Koç Museum, Istanbul; the Museo Naval, Cartagena, Spain; the Royal Navy Submarine Museum, Gosport; the Imperial War Museum, London; the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois; Baltimore Maritime Museum, Baltimore, Maryland; the Warren F. Lasch Conservation Center, Charleston, South Carolina; The Friends of the Hunley, Charleston, South Carolina; Buffalo Naval & Military Park, Buffalo, New York; Battleship Memorial Park, Mobile, Alabama; Battleship Cove Museum, Fall River, Massachusetts; the Paterson Museum, Paterson, New Jersey; Independence Seaport Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the Naval & Maritime Museum, Muskegon, Michigan; the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, Portland, Oregon; the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum, Vallejo, California; the USS Bowfin Museum and Park, Honolulu, Hawaii; the Connecticut River Museum, Essex, Connecticut; the Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada; Patriots Point Maritime Museum, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina; the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, Manitowoc, Wisconsin; the US Navy Submarine Force Library & Museum, Groton, Connecticut; the Naval Undersea Museum, Keyport, Washington; the Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia (US); the National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, Texas; the National Maritime Museum, San Francisco; the National Guard Militia Museum at Sea Girt; the US National Archives, Military Branch and Still Pictures Branch, Washington, DC and the US Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, DC; the Library of Congress, Washington, DC; and the US Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland.

The review and editing of my assistant, Kathy Smith, once again made the task of writing easier. I owe her my usual debt of gratitude. I also wish to thank the Osprey team, especially Kate Moore and Emily Holmes. Last, but not least, I thank my wife, Ann, for her constant support and love.

The diving bell, a technology dating back centuries, was illustrated in cross-section in this 1785 French drawing. Diminishing air, the threat of suffication, cold, and darkness were the conditions that pioneer divers faced when working below the surface. (Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library)

At the advent of the 21st century, the sea holds the unfortunate distinction of being humanity’s largest battlefield, the result of millennia of naval warfare. The bottom of the sea is littered with ships lost to combat that date to all periods of history, among them hundreds of submarines, along with 65,000 lost submariners, and thousands of other vessels sunk by submarines in the brief span of the last century when these silent killers struck, often without warning, to send ships and crews into the depths.

The heyday of the submarine came after centuries of experimentation, occasional tragedies, and the perseverance if not stubbornness of inventors. While hindrances along the way included the limits of technology, governmental indifference, and the occasional intransigence of various naval establishments, the principal obstacle was the nature of the sea itself. Though brimming with life, and covering two-thirds of the planet, the sea is an environment hostile to humanity.

Would-be warriors of the depths faced two basic problems – the human need for replenishable air in an aquatic environment in which we cannot breathe unassisted, and the cumulative effects of pressure the deeper one descends. A sealed container of air, without the technological ability to remove the build-up of carbon dioxide and replenish oxygen, quickly becomes toxic when a person breathes inside it. The pressure cumulatively builds, every 33ft adding one unit of pressure, known as an atmosphere. At one atmosphere, the pressure is 14.7lb/sq in (psi); at 103ft, the pressure is 46psi of constant pressure. Early scientists were not unaware of these problems. Solving them would take centuries of trial and error.

As technology advanced, the problems of submarine navigation became more complex. In 1880, at the advent of what would be the final push to the successful development of the modern submarine, the “qualifications essential to a submarine boat” were summarized thus:

1. It should be of sufficient displacement to carry the machinery necessary for propulsion, and the men and materials for performing the various operations.

2. It should be of such a form that it may be easily propelled and steered.

3. It should have sufficient interior space for the crew to work in.

4. It should be capable of carrying sufficient pure air to support its crew for a specified time, or of having the means of purifying the air within the boat, and exhausting the foul air.

5. It should be able to rise and sink at will to the required depth, either when stationary or in motion.

6. It should be so fitted that the crew possess the means of leaving the boat without requiring external assistance.

7. It should carry a light sufficient to steer by, and to carry on the various operations.

8. It should possess sufficient strength to prevent any chance of its collapsing at the greatest depth to which it may be required to manipulate it.1

Within 25 years of the writing of these qualifications, they had been met by submarine inventors. More than a century later, they have been surpassed far beyond the wildest dreams of the submarine engineers of the late 19th century, to an extent only dreamed of by fiction writers of the day.

Divers in a diving bell recover items from a shipwreck, 18th century. (Author’s Collection)

The concept of combat beneath the waves dates to antiquity. The 9th-century BC reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (in northern Iraq), recovered by archaeologists from the ruins in the 19th century and now in the British Museum, depict men swimming with inflated skins which may be breathing bags that allowed warriors to cross rivers undetected. Three centuries later, a Greek epigraph proudly but inaccurately credits one Scyllias with the invention of underwater warfare “when Xerxes’ huge armada invaded all of Hellas… Gliding down into the secret shallows of Nereus, he cut the mooring of the ships at anchor.”2 Other ancient writers described diving and war beneath the sea well into the late Classical age, including Herodotus, Thucydides, Arrian, and Dio Cassius. All of these accounts recount the exploits of naked, breath-holding divers who occasionally used breathing tubes cut from reeds or animal skins inflated with air.

The introduction of diving bells suspended from ships and built to trap air to provide a submerged working platform, provided divers with more access to the bottom of the sea, but their efforts were limited to salvage and recovery of sunken items. The concept of an auto-mobile craft of war, that would attack ships from a submerged or semi-submerged position, was introduced during the 16th century. Leonardo da Vinci secretly sketched a simple design for a submersible craft that would carry a warrior below the sea, but noted he would not pursue such an invention “on account of the evil nature of men, who would practise assassinations at the bottom of the seas by breaking the ships in their lower parts and sinking them together with the crews who are in them.”3

William Bourne (c.1535–82), who described himself as a “poore gunner,” wrote of his plans for a “Shipe or Boate that may goe under the water unto the bottom, and so to come up againe at your pleasure” in 1578.4 The earliest complete proposal for a submarine, Bourne’s description of his wooden-hulled craft shows that he relied on leather that lined the inside of the boat to regulate its ability to dive and surface, and a hollow mast to carry fresh air to the crew. By tightening and loosening large screws to slacken and then compress the leather, Bourne figured he could admit and then expel water to regulate the boat’s buoyancy.

Bourne never built his craft, but decades later, in the early 1620s, a Dutch inventor living in London, Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633) built a submersible craft that followed Bourne’s basic principle. Described by his contemporaries as an inventor, chemist, engineer, naturalist, and mathematician, as well as a sorcerer, alchemist, charlatan, braggart, jackass, and “strange monster,” Drebbel used Bourne’s principle of buoyancy to build a sharp-ended craft propelled by oars that passed through watertight gaskets.5 In 1662, physicist, inventor, and chemist Robert Boyle wrote how “more than a few credible persons” affirmed that Drebbel had built “a vessel to go underwater, of which trial was made in Thames with admired success; the vessel carried twelve rowers besides passengers.”6

A friend of Drebbel’s noted that “this bold invention” could carry a “battering ram” by which “enemy ships could be secretly attacked and sunk unexpectedly.”7 According to historian Alex Roland, Drebbel and his son-in-law Abraham Kuffler built “water engines” for action against the French at La Rochelle in late 1627. But the craft, which may have been a copy of Drebbel’s submersible boat, failed to achieve any results.8

Other semi-submersible craft, proposed (and some built) followed, including another variation of Bourne’s principle by Italian scientist Giovanni-Batista Borelli (1608–79), whose posthumous publication De Motu Animalium (1680) included a submarine raised and lowered by leather ballast bags. Denis Papin (1647–1712), a protégé of Drebbel’s friend Constanyn Huygens’ son, the physicist and astronomer Christiaan Huygens, built two small submarines in Marburg, Germany, which he described in 1695. The craft were ingenious, employing surface-supplied air, pumps, variable ballast, and holes by which the operator could “touch enemy ships and ruin them in sundry ways.”9 While Papin’s craft were not adopted by his patron, the Landgrave Charles of Hesse-Cassel, his design probably inspired later inventor David Bushnell.10

Stone panel from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal depicting men swimming in or under the Euphrates in the 9th century BC. (The British Museum)

In the mid-part of the 18th century, inventors revisited the earlier concepts of submarine design.11 In December 1747, the Gentleman’s Magazine described Papin’s submarine and illustrated it. Two years later, letters in the magazine discussed and illustrated Borelli’s system of collapsible leather bags for a submarine craft, and went on to note that one Nathaniel Symons had built a submersible using this method, an apparent unacknowledged borrowing of Bourne and Borelli’s ideas. Symons, a “common house carpenter,” took his submarine boat “to the middle of the river Dart, entered his boat by himself, in sight of hundreds of spectators, sunk his boat by himself, and tarry’d three quarters of an hour at the bottom; and then … he raised it to the surface again without any assistance.”12

Cornelis Drebbel’s underwater rowing boat, c.1620. It could allegedly stay under the water, at a depth of 12–15ft for some hours. There was space for 12 rowers. (Ullstein Bild/akg-images)

The next inventor, a ship’s carpenter named John Day (c.1740–74), was not as fortunate as Symons. In 1774, Day modified the 50-ton, 31ft-long sloop Maria into a submersible craft. Historian Richard Compton-Hall describes Day as an “odd, solitary individual, addicted to dark waters” as well as gambling.13 The venture with Maria would prove to be a fatal wager. After building a small, watertight chamber in a “small market boat” that Compton-Hall believes Day beached, sealed himself inside and then let the high tide cover, the ambitious carpenter wrote to a Mr Christopher Blake to seek financing for a larger vessel to be taken down to up to 100yd (300ft) deep for 24 hours.14 Bets placed on how long Day could remain submerged would not only pay for the venture, but also handsomely reward Blake and Day.

Papin’s submersible, from Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, 1747. (Author’s Collection)

Blake agreed, but fearing that Day was seeking to go too far, modified the terms to 12 hours, and depths no greater than 20 fathoms (120ft), urging Day “at any expense to fortify the chamber … against the weight of such a body of water.” The terms agreed, Day purchased Maria for £340 and in March 1774 modified the sloop at Plymouth, building a timber diving chamber 12ft long, 9ft wide, and 8ft deep that projected above the level of the main deck. To dive, two plugged openings in the hull near the keel flooded Maria, and to surface, from inside the chamber Day could turn iron rods that released 20 tons of rock, suspended from the bottom of the hull in nets. Day could also release color-coded signal buoys that would notify those on the surface of his condition, ranging from “very well” to “very bad.”15

On June 20, 1774, Day and Maria prepared to dive in Plymouth Sound off Drake’s Island. The bottom was 22 fathoms (132ft) below. Pulling the plugs to flood Maria, Day waited until the deck was awash, and then sealed his hatch as the sloop went down, stern first. From a nearby barge, Blake watched “with a pensiveness that seemed to forebode to his mind an evil omen, and a solemn silence seized all the witnesses of the extraordinary and awful sight.”16

About 15 minutes later, the surface of the water was “suddenly agitated, as if boiling.”17 The reinforced chamber had collapsed under pressure of 58lb/sq in and Day lost not only his wager, but his life. Despite efforts to salvage Maria that went on for some time, the vessel could not be raised. More than two centuries later, John Day and Maria still rest on the seabed of Plymouth Sound. The loss of the vessel and a life to an ill-advised wager did not, however, deter the next inventor, David Bushnell, who built his own craft just a year later. Bushnell, an American, was inspired not by money but by patriotism in time of war to create the world’s next submarine – and he lived to tell the tale.

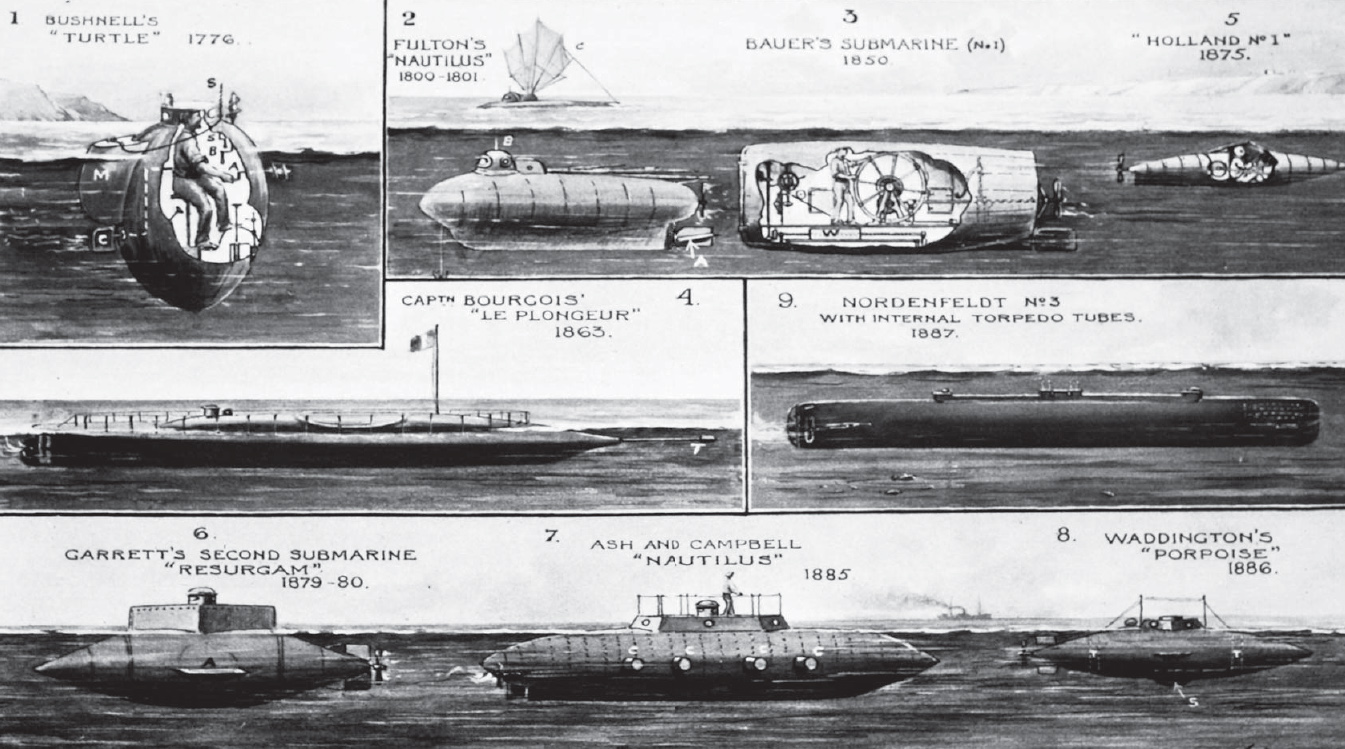

The evolution of the submarine up to 1886, as depicted by The Illustrated War News. (The Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Robert Fulton, 1765–1815, who shared Bushnell’s enthusiasm for the submarine. (The Bridgeman Art Library)

David Bushnell (1740–1824) of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an innovator who practiced his craft on both the submarine and the weapon future submarines would carry into combat, the “torpedo.” Working with his brother Ezra and a small group of craftsmen in 1775, he built a small, one-person submarine to wage war on British ships at the start of the American Revolution. An older student at Yale (aged 31), Bushnell began his quest to build a submarine during his first semester there in the spring of 1775. Seeking support from Connecticut Colony, but rejecting its offer of funding as “inconsiderable,” he decided to proceed “at his own Risque.”1 That summer Bushnell and Erza built a small wooden hull, turning to Phineas Pratt of Saybrook to forge the necessary ironwork for it. Isaac Doolittle of New Haven, a mechanic and clock-maker, built a force pump to enable the vessel to be raised to the surface after a dive. Bushnell apparently had the two craftsmen do their work speculatively and in anticipation of eventual government sponsorship or award.

Described in August 1775 as having “the nearest resemblance to the two upper shells of a tortoise joined together,” the craft, named Turtle, “doth not exceed 7½ feet from the stem to the upper part of the rudder; the height not exceeding 6 feet.”2 The ellipsoidal wooden hull was covered in tar and reinforced with iron bands and an internal beam that would keep it from crushing under pressure. Bushnell forged or cast a small conning-tower with glass portholes and installed it atop the hull. “The person who navigates it enters at the top. It has a brass top or cover, which receives the person’s head as he sits on a seat.”3

Ballasted with lead and propelled and steered by hand-cranked rudders and “oars,” Turtle dived when a foot-operated valve admitted water into the bottom of the hull. The pump built by Doolittle took the water out of the hull to bring Turtle back to the surface. Bushnell ballasted the submarine with 900lb of lead, 200lb of which was rigged externally at the base of the craft to be dropped for emergency ascent. Closable air valves, a ventilator/snorkel, and a compass to navigate as well as “a water gauge or barometer” completed the submarine’s basic configuration. In its basic form and function historian Alex Roland finds a link between Turtle and Papin’s second, wooden craft of 1695, with an internally braced, externally reinforced wooden hull, a single hatch on top, a dive system that allowed water into the hull, and the same basic dimensions for a single operator to attack and sink ships.4

Bushnell’s Turtle, as imagined in the 19th century. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

To carry out his craft’s deadly purpose, Bushnell fixed a detachable, “large powder magazine,” to Turtle and designed a “wood screw” or auger that passed through the top of the sub to help set the charge. Once in place below the ship it was to attack, the operator would rotate the screw by hand so that the auger bit into the wooden hull above. Then the operator would detach both it and the magazine and back away. The auger had an eye at its end with a rope that passed through it to the magazine. As the sub backed away, the rope would pull tight, setting the charge up against the ship’s hull and starting a clockwork detonator. When the detonator had run down, a flintlock inside the magazine would strike and set off the powder charge to sink the ship.5

According to various accounts, Bushnell tested Turtle, perhaps as early as November 1775, before sending it into combat in the early fall of 1776. Bushnell’s brother was to be the operator, but illness prevented him from going. In his stead was a volunteer, Sergeant Ezra Lee of the Continental Army. In an 1815 letter, Lee reminisced:

It was high enough to stand in or sit as you had occasion, with a composition head hanging on hinges. It had six glasses inserted in the head and made water tight, each the size of a half Dollar piece to admit light. In a clear day a person could see to read in three fathoms of water. The machine was steered by a rudder having a crooked tiller, which led in by your side through a water joint; then sitting on the seat, the navigator rows with one hand and steers with the other … with hard labour, the machine might be impelled at the rate of 3 nots [sic] an hour for a short time.6

On September 6, 1776, with Lee inside, Turtle set out to sink HMS Eagle, flagship of Lord Richard Howe, then moored off New York. Lee later recounted that whaleboats towed him as close as they dared, then cast him off to wait for the tide. An hour before dawn, Lee maneuvered beneath Eagle’s stern, sank Turtle and came up under the bottom of the ship. As he turned the auger to try and bite into the wood, however, he found that “it would not enter. I pulled along to try another place, but deviated a little to one side and immediately rose with great velocity and came above the surface 2 or 3 feet between the ship and the daylight, and sunk again like a porpoise.”7

Briefly considering another try, Lee decided to head for home, facing a 4-mile trip back in daylight. Running on the surface and zigzagging, he attracted the attention of British troops ashore. When they launched a boat to intercept him, Lee jettisoned the magazine, so that if caught it would detonate and “we should all be blown up together.”8 The men in the boat from shore, seeing the magazine float free, retreated, allowing Lee to make his escape as the charge finally erupted, “throwing up large bodies of water to an immense height.”9

Lee and Turtle made one more attempt, this time to sink a frigate off Bloomingdale on the Hudson River. As he tried to set the charge close to the water line, however, Lee was discovered. Diving too deep, he missed the frigate’s hull and retreated. Pursued by the British frigate, the American sloop and galley that carried Turtle and its crew did not escape, however, and the frigate sank them after the crew abandoned the two craft.10 Bushnell turned away from further attempts at submarine warfare, noting that in the future, “the operators should acquire more skill in the management of the vessel, before I could expect success” but that he could not proceed in any event, as he was “unable to support myself.”11 Instead he turned his inventive genius to floating “infernal devices,” or mines.

Some historians doubt Sergeant Lee and Bushnell’s accounts. Among them is submarine expert Richard Compton-Hall, who notes that Eagle’s log, as well as those of surrounding ships, does not mention any unusual events that evening or in the morning, such as an explosion. Compton-Hall also dismisses Lee’s account, noting what he feels are physical impossibilities and discrepancies in it. With the available tools and materials, “David and Ezra simply could not have done the job,” Compton-Hall writes; he is not even sure that the craft was built.12

To bolster his claim, Compton-Hall notes that in letters between Thomas Jefferson and George Washington in 1785, Jefferson asked Washington to Washington answered that he could not remember much, but that Bushnell “is a man of great mechanical powers, fertile in inventions, and master in execution.” He recalled that Bushnell had approached him in 1776, that he had given him “money and other aids,” and with that support Bushnell had built a craft, but “he laboured for some time ineffectually; and although the advocates for his schemes continued sanguine, he never did succeed.”14

be so kind as to communicate to me what you can recollect of Bushnell’s experiments in submarine navigation during the late war, and whether you think his method capable of being used successfully for the destruction of vessels of war. As not having been actually used for this purpose by us, who were so peculiarly in want of such an agent, seems to prove it did not promise success.13

Handshouse Studio in the US are among those who have sought to recreate Bushnell’s Turtle. (Courtesy of Trillium Studios and Handshouse)

Side and top views of Turtle.

Ultimately, Compton-Hall concluded that the saga of Turtle is a patriotic fraud, with a likely scenario being the construction of the “rudiments of a submersible (perhaps upending one cockleshell boat on another)” and that if Lee did venture forth, it was in “some kind of skiff with muffled sculls” and his auger, powder charge, and detonator line hidden beneath a tarp.15 Other historians, notably Alex Roland, disagree.

One means by which archaeologists seek to separate legend from reality, and fact from fiction is through experimental archaeology, whereby drawing on both the literature and physical evidence, technology and events from the past are recreated to see where the truth lies. In 2002, Rick and Laura Brown, professors at the Massachusetts College of Art and the operators of the Handshouse Studio, a center dedicated to the intense study of objects in history, set out to recreate Turtle using the materials, tools, and technology of the time. Working from the archives, drawing on Bushnell’s and Lee’s descriptions, and also from a detailed understanding of 18thcentury American technology, the Browns invited a specialist team including cadets from the US Naval Academy to join them in the design and construction of a new Turtle as a working replica.16

Creating a hull from a large log that was split and hollowed to make the two halves of the craft (the team borrowed a local boatbuilding tradition from the Pequot, the First Nations people of the area as the most logical approach for structural support against water pressure), they also cast bronze, braised it, blacksmithed the iron components, blew glass, and did copper work.17 In ten days the craft was completed, and test dives on January 9–10, 2003, in Duxbury, Massachusetts’ Snug Harbor found that when flooded knee-deep, it dived but retained its watertight integrity. Subsequent tests at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in March 2003 assessed the new Turtle’s watertightness and hydrodynamic performance.

In a water tank test conducted by Professor Lew Nuchols of the US Naval Academy, “albeit with difficulty,” Nuchols was able to recreate Lee’s actions, successfully screwing into a replica wooden hull and attaching a mock bomb. In a final test, back at Duxbury, the team demonstrated how a traditional horse and cart method of launching could have deployed Turtle in 1776.18 Another replica project, undertaken by Old Saybrook High School in Connecticut and the US Naval Undersea Warfare Center, also successfully built and tested a “replica Turtle” between 2003 and 2007 in the Connecticut River.19 Both of these exceptional projects clearly show that the principles of Turtle’s design, as documented, are sound, and that with the tools and technology available to them, Bushnell and Lee could both have been telling the truth.20

Handhouse tested their Turtle on the river in January 2003.

An illustration of a longitudinal section plan of Fulton’s Nautilus, 1798. (Peter Newark Historical Pictures/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Bushnell’s interest in both submarine craft and explosive charges, or “torpedoes” was picked up by another American, Robert Fulton (1765–1815), who like Bushnell was a native of Connecticut. Affable, inventive, and brilliant, Fulton made his way to France in 1797 to seek support for his plans for improving canal navigation. Bushnell lived in France after the American Revolution, and it has been suggested that Fulton, on a visit in 1790, may have met Bushnell, and enthusiastically learned of submarines and torpedoes. A more likely source of information and inspiration was Joel Barlow, American statesman and diplomat then living in Paris. Barlow had attended Yale when Bushnell was there, and Barlow’s brother-in-law was a close friend of Bushnell’s.21

Six months after arriving in Paris, Fulton presented a proposal to the French Government to build a “mechanical Nautulus” as a submerged weapon of war against Britain.22 An advocate of free trade and opposed to naval power, which he saw as evil, Fulton proposed the “Nautulus” and “un toute expedition sous-marine” (an all submarine expedition) as a tool and a means for the French to break the naval power of their ancient enemy.23 Interest in Fulton’s proposal waned and waxed with changes in the Revolutionary government of France, but in September 1798, a seven-man commission, having reviewed Fulton’s plans, enthusiastically endorsed them as the “first conception of a man of genius.”24

Now correctly spelled as “Nautilus,” Fulton’s drawings of his proposed submarine depicted a metal-hulled craft with an ellipsoidal, elongated hull capable of carrying three or more crew members. A sealed, hollow iron keel, flooded and drained by a pump, provided the necessary ballast to dive. A domed turret or conning-tower topped the hull. A single propeller, powered by a hand-cranked mechanism, powered the sub, and a vertical and horizontal rudder steered it. The craft’s main propulsion, however, was a collapsible rig. This allowed the crew to sail into position and then submerge to attack. The weapon, towed on a line behind the sub, was a floating torpedo. The French commissioners described the proposed Nautilus as “a means of terrible destruction, because it acts in silence and in an almost inevitable manner.”25

Fulton and the commissioners also saw this new craft as a weapon by which a weaker nation could not only strike at but even defeat a greater power – namely Britain. “It is particularly suited to France … having a feebler navy than its adversary…”26 British officials were quick to respond, deriding Fulton. In answer to British criticism of his plans, Fulton argued that the destruction of naval power would bring an end to tyranny and secure the freedom of the seas, as well as protect his home and native land. “The idea is yet an infant but I think I see in it all the nerve and muscle of an infant Hercules which at one grasp will strangle the serpents which poison and convulse the American Constitution.”27

Despite being an “infant Hercules” and the commissioners’ accolades, Fulton’s submarine did not gain official French naval approval until the end of 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’état placed P. A. L. Forfait, one of the commissioners of 1798, in the position of Ministère de la Marine. Fulton proceeded to build his submarine out of copper attached with iron bolts to an iron frame at the yard of Perrier Frères in Paris. Known variably as Nautilus and as the Bateaux Poisson, the 21ft 3in-long, 6ft 4in-wide submarine slid into the Seine on June 13, 1800. The first trial was reported by Forfait in a letter to Napoleon: “le bateau plonge et se d’emerge avec beaucoup de facilité. Les hommes qui le manoeuvre sont restés 45 minutes son renouveler l’air dans l’interieur du Bateau, et quand ils sont sorti il nes paraissait sur le visage aucune alteration.”28 [The boat dives and emerges with great ease. The men who maneuvered it remained 45 minutes, introducing fresh air into the interior of the boat, and when they emerged, there was no change to their faces.] After this 45-minute dive, which took place in front of the Hôtel des Invalides, and without any ill effects on the three-man crew (which included Fulton), further tests were planned because the Seine was too fast and too shallow to test Nautilus’ maneuverability and its ability to withstand pressure.

The next test of Nautilus was further down the Seine at Rouen, where Fulton added a wooden deck for his crew to stand on when the submarine was on the surface. Relaunched on July 24, Nautilus conducted its second dive test on the 29th. Two dives to 25ft proved the hull’s pressure-worthiness, but the current prevented Fulton from achieving a proper test of the craft’s steering. The time had come for sea trials. The first was on August 24 at Le Havre, where Fulton dived to 15ft for over an hour. After assessing the sub’s surface speed by matching his crew’s hand-cranked exertions against a rowboat, he then tested the trim, a surface-supplied leather air hose and float (a primitive snorkel) and the compass’ performance in correctly navigating Nautilus. Fulton also tested his floating bomb, which he termed a “carcass,” by towing a 30lb black powder charge in a copper canister behind the submarine and into a barrel. Borrowing from Bushnell’s earlier “torpedoes” with their flintlock mechanism, Fulton’s “carcass” successfully detonated on contact.29 On September 12, Fulton and his crew set out for La Hougue to test the vessel in open sea conditions. Rough seas plagued the trip, but Nautilus proved its seaworthiness in one six-hour stint underwater, before being forced ashore.

Robert Fulton’s “Plunging Boat” submarine as seen beneath the waves. (Library of Congress)

Cross-section illustration of Fulton’s “Plunging Boat.” (Library of Congress)

Successful performance was key, because Fulton was seeking not only French support for his craft, but also a commission to sink British ships, and a bonus for each vessel he destroyed. In his initial proposal to the French Government in 1797, Fulton had offered to pay for the submarine’s construction in exchange for prize money paid for each British ship he sank. He also requested commissions for himself and his crew to avoid being executed as pirates if captured. As the tests of Nautilus continued, Fulton renewed his requests for commissions and prizes. Thanks to French friends, Fulton secured a meeting with Napoleon at the end of 1800, but his briefing did not result in a personal intervention, rather a referral back to the bureaucracy with whom Fulton was dealing. Formal approval was not long in coming, however, and in February 1801, Fulton received notice of a 10,000 franc award to conduct more tests, and an agreement to pay rewards when Nautilus sank British ships.

Fulton’s sighting apparatus for his submarine, with the inventor himself peering through it. Fulton personally drew these plans. (Library of Congress)

Working from Brest, where he repaired corrosion damage to the sub, installed a glass deadlight in the conning-tower to better illuminate the sub’s interior, and introduced a “portable container” of compressed air, Fulton conducted further tests in July and August 1801, including one dive to 25ft and another when Nautilus and its crew remained submerged for four hours and 20 minutes.30 The big test, however, was sinking a ship using the bombs Fulton towed behind Nautilus. It is not entirely clear whether the bomb used in the test was towed by the submarine or by a pinnace on the surface; Fulton’s biographer Wallace Hutcheon believes it was the latter.

On August 12, 1801, Fulton approached his target, a 40ton sloop, off Brest, towing a 20lb explosive charge in a copper container. Approaching the sloop, Fulton swerved, and the bomb swung into the sloop and detonated. The resulting explosion sank the vessel, a small but dramatic moment marking the beginning of a new era in naval warfare in which underwater weapons, not ship-to-ship combat, would destroy ships. Having proven his craft and its weapon, Fulton reportedly cruised the coast seeking, but not getting close enough to engage British ships.

Enthusiastic reviews of Fulton’s submarine and its revolutionary nature appeared in the press and in early September 1801, on his return to Paris, Fulton was informed that Napoleon wanted to see Nautilus. He wrote that he was sorry that he had not learned earlier of Napoleon’s wishes, because he had after his experiments with the sub found it not only “leaking” but also “an imperfect engine” and had thus taken her to pieces, “So that nothing now remains which can give an idea of her combination.” Fulton continued:

… I refuse to exhibit my drawings… For this I have two reasons; the first is not to put it into the power of anyone to explain the principles or movements lest they should pass from one to another till the enemy obtained information; the second is that I consider this invention my private property … which … ought to secure me an ample Independence.31

This effectively ended Fulton’s relationship with the French Government. Fulton remained in France through 1804, painting, touring with friends, and gradually developing a new invention, the perfection of a steam-powered vessel. This he also presented to the French Government and Napoleon, but the idea languished and finally, in April of that year, Fulton departed France under an assumed name for England, lured by agents of his one-time ostensible enemy to try his hand at his inventions there.

Fulton met with British officials and began to draw up plans for new submersibles; one was for a single operator, 9ft-long craft he dubbed Messenger. He also designed a second, larger craft that some historians have referred to as a second Nautilus. Looking like a traditional sailing sloop, the submarine had just the same watertight, pressure-resistant hull and conning-tower just forward of a single mast that hinged down for diving. A tiller and rudder that could be steered from the deck was also controllable from below in the crew compartment, and a hand-cranked propeller that disengaged and tilted up to help streamline the craft’s sailing performance when on the surface drove it when submerged. The 30ft by 10ft craft was to accommodate a six-man crew, be capable of remaining at sea for 20 days, and was equipped with an internal, centrally mounted tear-drop-shaped anchor whose cable passed through a watertight gland to allow the craft to moor beneath the surface to wait for victims.32

However, Fulton’s proposals for submarines, referred to a British board of commissioners, never received approval as they were deemed “impracticable in combat.”33 The indefatigable Fulton turned his attention, and his hosts’ to his carcasses, or submarine bombs, which he was increasingly styling with a term first used by David Bushnell, “torpedo,” after the Atlantic ray (Torpedo nobiliana) which emits strong electric shocks of up to 200 volts.34

With a contract signed in July 1804, Fulton proceeded to build and test his “torpedoes” both in English waters and in a combat foray against the French fleet at Boulogne in September 1804 and again at the start of 1805. The two combat operations were unsuccessful, and so he arranged a test – a torpedo run against an anchored Danish brig, Dorothea, which had been purchased as a target. Anchored off the coast near Deal, England, in sight of Prime Minister Sir William Pitt’s country estate, Walmer Castle, Dorothea sat where Fulton hoped prominent government and naval observers would watch it blow up. With two boats towing 180lb charges, a successful attack on October 15, 1805 blew Dorothea in two and sank it. The Admiralty was impressed and Fulton received a promised cash award, but his dreams of greater glory were dashed by Nelson’s victory at `Trafalgar on October 21 and the resultant crushing of French sea power. No further experiments ensued, and Fulton spent several months seeking compensation. In August 1806, he received a small final reward for his services, which were no longer required, and in November he departed for the United States.

On the subject of his torpedoes, Fulton faced not only official indifference but also criticism from British naval officers. Admiral George Berkeley bluntly referred to the “Baseness & Cowardice of this species of Warfare,” while a more junior officer referred to it as “unmanly, and I may say assassin-like.”35 Fulton’s response, penned in 1810, was unambiguous as well: “But men, without reflecting, or from attachment to established and familiar tyranny, exclaim, that it is barbarous to blow up a ship with all her crew. This I admit, and lament that it should be necessary; but all wars are barbarous, and particularly wars of offence…” By developing and using the torpedo, however, Fulton argued that the great destructive power of the weapon would by itself “prevent such acts of violence, the invention must be humane.”36

Back in the United States, Fulton offered his services to his country, conducting a torpedo test in New York harbor on July 20, 1807. After two abortive attempts, the third sank a 200ton brig. The United States was then in a period of heightened tension with Great Britain, and Fulton’s return and his test were not lost on President Thomas Jefferson, who inquired not only about Fulton’s torpedoes but also his “submarine boat.”While the inquiries about the submarine went nowhere, Fulton’s torpedo experiments continued with Government approval and funding through 1810 although, once again, a Government commission concluded that Fulton had not “proved that the government ought to rely on his system as a means of national defence.”37 While some of Fulton’s mines were discovered and unsuccessfully used against British ships during the War of 1812, and another inventor deployed a semi-submersible “turtle boat” though to no avail in 1814, the time was not yet right for either the submarine or the torpedo in naval warfare. However, accounts of Fulton’s work and discussions of his craft were widely distributed and translated, and submarine historian Norman Friedman suggests that this, especially the idea of combining the submarine and the “torpedo,” had a substantial impact on the work of other inventors.38 While trial and error continued through the first three-quarters of the 19th century, the successful merger of Fulton’s concepts would come and with deadly effect in the 20th century, as submarines successfully delivered underwater explosives to a target.

Jules Verne famously wrote Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea in 1869. This illustration shows his hero, Captain Nemo, determining the position of the Nautilus with a sextant. (akg-images)

The 19th century was a time of unprecedented technological and scientific advances that propelled a second industrial revolution during the second half of the period. It was the era in which the talented amateur gave way to the professional scientist, and in which new inventions were developed that would, in the following century, change the world. These included the development of industrial iron and steel, plastic and vulcanized rubber products, the discovery of the properties of the atom, the general adoption of the assembly line, the use of machine tools, the invention of the photograph, mechanical computational devices and telecommunications, and the processing of petroleum into fuel. It was also the century in which the modern submarine took shape.

Robert Fulton’s turn of the century experiments with submarines and torpedoes attracted a great deal of attention in public as well as military and political circles. In December 1806, as Fulton returned to the United States, a prominent newspaper exclaimed that his homecoming was “an important acquisition to our country … and we cannot but hope that his system of submarine navigation may be advantageously united with our gun boats, to form the cheapest and surest defence of our harbors and coasts.”1L’Invisible2