CONTENTS

Preface

Acronyms And Abbreviations

Section 1: Mammalian Hematology Case Studies

1. A 6-year-old otter undergoing a routine physical examination,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

2. A 10-year-old ferret with lethargy and anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

3. A 6-year-old ferret with anorexia and lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

4. A 2-year-old ferret with weight loss and lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

5. A 3-year-old rabbit with anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

6. A 6-year-old hedgehog with anorexia and ataxia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

7. A 7-year-old guinea pig with anorexia and decreased water intake,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

8. A3V2-year-old ferret with lethargy and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Findings from Previous Visits

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 2: Avian Hematology Case Studies

9. A 1 -year-old parrot with an acute onset of severe illness,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

10. A 2-year-old chicken with lethargy, inappetence, and lack of egg laying,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

11. A 14-year-old macaw with feather-picking behavior and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

12. A 14-year-old parrot with weakness, anorexia, and labored breathing,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

13. A 4-year-old parrot with anorexia, weakness, and lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

14. An adult vulture with generalized weakness,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Summary

15. A 2-year-old tragopan with wounds,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

16. A5-month-old chicken with lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

17. A 4-year-old budgerigar with generalized weakness and breathing heavily,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

18. A4V2-year-old duck with acute dyspnea,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

19. A 14-year-old falcon with anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

20. An 8-month-old hawk with anorexia, weakness, and vomiting,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

21. A juvenile kestrel with a drooping right wing and blood in the left nares,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 3: Herptile Hematology Case Studies

22. A 20-year-old turtle with lethargy and anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

23. A 3-year-old lizard with lethargy and keeping the eyes closed,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

24. An 18-month-old lizard with an oral mass,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

25. A 35-year-old tortoise with anorexia, lethargy, and constipation,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

26. An adult turtle with a fractured carapace and leg laceration,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

27. A 2-year-old lizard with anorexia and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 4: Fish Hematology Case Studies

28. An adult stingray with weight loss and lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

29. An adult stingray undergoing a routine physical examination,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 5: Mammalian Cytology Case Studies

30. A 6-year-old guinea pig with excessive drinking and urination, soft stools, and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

31. A 2-year-old rat with diarrhea, dry skin, and squinting eye,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

32. A 6-year-old tiger with two masses in her mouth,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

33. A 10-year-old lion with weight loss and lethargy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

34. A5 72-year-old ferret presented for a presurgical evaluation,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

35. A 4-year-old ferret with a tail mass,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

36. A 5-year-old rabbit with a mass near the left nostril,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

37. A 1-year-old chinchilla with a closed eye,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 6: Avian Cytology Case Studies

38. A 5-year-old ferret with a swollen head,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

39. A 2-year-old rat with a swelling around the left inguinal area,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

40. A 5-year-old ferret with lethargy, dyspnea, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydypsia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

41. A 3-year-old guinea pig with anorexia and decreased water intake,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

42. A 9-year-old ferret with a mass on the ear,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

43. A 3-year-old ferret with lethargy and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

44. A 3-month-old ferret with a prolapsed rectum,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

45. A 2:2-year-old gerbil with lethargy and anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

46. A 5-year-old guinea pig with an ulcerated swelling in the abdominal area,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

47. A 6-year-old ferret with pawing at the mouth,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

48. A 7-year-old ferret with bilateral alopecia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

49. A 20-year-old parrot with dyspnea, weight loss, and persistent ascites,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Testing

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

50. An 11-year-old cockatiel with a mass in the ear,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

51. A 4-year-old cockatiel with a swollen head,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

52. An adult owl with a swollen elbow,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

53. A 2-year-old macaw with left leg lameness,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

54. A 6-year-old lovebird with dystocia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

55. A 5-year-old parrot with dyspnea,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information during Initial Visit

Interpretive Discussion for the Initial Visit

Summary for Initial Visit

Interpretative Discussion

Summary

56. A 2-year-old macaw with anorexia and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

57. An adult goose with a mass on the wing,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

58. A 14-year-old budgerigar with lethargy and anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

59. A 35-year-old parrot with weight loss and dyspnea,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

60. A 29-year-old parrot with halitosis and reduced vocalization,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

61. A 6-month-old cockatiel with labored breathing,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

62. A 13-year-old parrot with a prolapsed cloaca,

Signalment

History

Interpretive Discussion 1

Summary 1

Physical Examination Findings on Day 7

Interpretive Discussion 2

Summary 2

63. A 17-year-old cockatoo with broken blood feathers,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

64. An adult duck with a mass on the rhinotheca,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

65. A 3-month-old flamingo with a mass on the rhinotheca,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 7: Herptile Cytology Case Studies

66. A 2-year-old lizard with difficulty breathing,

Signalment

History

Physical Exam Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

67. A 3-year-old lizard with vomiting and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

68. A 9-year-old lizard with a mass near the vent,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

69. A 19-year-old lizard with a large mass on its leg,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

70. An 11-year-old lizard with an oral mass,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

71. A 10-year-old snake with a coelomic mass and concern of intestinal impaction,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

72. A 9-month-old lizard with anorexia and weight loss,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

73. A 6-year-old lizard with a tail mass,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

74. A 27-year-old snake with a snout lesion,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

75. A 1-year-old lizard with multiple infections,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretative Discussion

Summary

76. An adult snake with severe dyspnea,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

77. An adult newt with a white skin lesion,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

78. An adult frog in a moribund condition,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

79. A 10-year-old lizard with anorexia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

Section 8: Fish Cytology Case Studies

80. An adult eel with anorexia and skin lesions,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

81. A1 72-year-old goldfish with dropsy,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

82. A 6-year-old fish with a red mass protruding from the vent,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

83. An adult stingray with skin masses,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

84. An adult fish with a mass projecting from the gills,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

85. A 5-year-old fish with bloating and constipation,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

86. An adult fish with lesions around its mouth,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

87. An adult fish with a large red mass on its belly,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

88. A 3-year-old fish with a growth below the eye,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

89. An adult fish with increased gilling and eye lesions,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

90. A fish that is a sole survivor of a massive fish die-off,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

91. An adult stingray presented for examination for coccidia,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Other Diagnostic Information

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

92. An adult fish with a large mass on its operculum,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

93. An adult fish with a mass on its side,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

94. An adult fish with ulcerative skin lesions,

Signalment

History

Physical Examination Findings

Interpretive Discussion

Summary

References

Index

Edition first published 2010

© 2010 Terry W. Campbell and Krystan R. Grant

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Editorial office

2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information abouthowto applyfor permission to reuse the copyrightmaterial in this book, please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by Blackwell Publishing, provided that the base fee is paid directly to the CopyrightClearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For those organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payments has been arranged. The fee codes for users of the Transactional Reporting Service are ISBN-13: 978-0-8138-1661-6/2010.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and productnames used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Campbell,TerryW.,1949-

Clinical cases in avian and exotic animal hematology and cytology / Terry W. Campbell and Krystan R. Grant.

p.; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: “Clinical Cases in Avian and Exotic Animal Hematology and Cytology demonstrates howto use hemic cytology and cytodiagnosis as partof the assessment of an exotic animal patient. The clinical case presentation uses a hands-on, practical approach to facilitate learning, teaching, and comprehension. Well-illustrated throughout, each case presents the signalment, history, and physical exam findings. It then moves on to interpretive discussion and summarizes how to use the techniques in clinical practice. This book serves as a helpful guide for exotics veterinarians, zoo and aquarium veterinarians, and veterinary hematologists”-Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-8138-1661-6 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Veterinary hematology-Case studies. 2. Veterinary cytology-Case studies.

3. Birds-Diseases-Diagnosis-Case studies. 4. Exotic animals-Diseases-Diagnosis-Case studies. I. Grant, Krystan R. II. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Animal Diseases-diagnosis-Case Reports. 2. Animal Diseases-therapy-Case Reports. 3. Cytodiagnosis-veterinary-Case Reports.

4. Hematologic Tests-veterinary-Case Reports. SF 771 C174c 2010]

SF769.5.C36 2010

636.089'615-dc22

2009045135

A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library ofCongress.

Disclaimer

The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained here in may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising here from. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as acitation and/or apotential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

1 2010

PREFACE

This book provides representative examples of hematology and cytology cases encountered in exotic animal practice. Cases in the book were selected based on the important role of cytodiagnosis or hematology in the medical management of the exotic animal patient. The cases in the book offer a variety of hematologic and cytodiagnostic interpretations.

Cases representing animals with anemia include blood loss, hemolytic, iron deficiency, Heinz body, and nonregenerative anemia. An example of polycythemia as well as the effects of lead toxicosis on the hemogram is provided. A variety of abnormal leukograms, such as leukocytosis, leukopenia, leukemia, and stress responses, are represented in the text. Representations of normal and abnormal hemic cytologies are provided. These include normal hemic cells, toxic neutrophils and heterophils, left shifts, and leukemia. Blood parasites, such as Leukocytozoon, Hemoproteus, Plasmodium,and Hemogregarine, and bacteremia are also represented.

Example cases of the basic cytodiagnosis interpretations are also represented. These include normal cytology, inflammation, hyperplasia or benign neoplasia, and malignant neoplasia. Inflammatory lesions are represented by neutrophilic or heterophilic, mixed cell, macrophagic, and eosinophilic inflammation. Along with these inflammatory lesions, a specific etiologic agent, such as bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, viral, parasitic, or foreign body, is represented. Tissue hy-perplasia or benign neoplasia is represented by epithelial hyperplasia, papilloma, adenoma, lipoma, mast cell tumor, and chondroma. Representations of malignant neoplasia include carcinomas, such as undifferentiated carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma; sarcomas, such as undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma, liposarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, and malignant melanoma; and discrete cell neoplasms, such lym-phoma, histiocytoma, and mast cell tumor.

Effusions are also represented. These include tran-sudate, modified transudate, exudate, and hemorrhagic effusion. Examples of specific fluid analysis include synovial fluid, such as articular gout and synovial cysts, and a salivary mucocele.

Guideline for Using the Clinical Cases Presented in this Book

This book is offered as a companion to TW Campbell and CK Ellis, Avian and Exotic Animal Hematol-ogy and Cytology, Ames, Iowa, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, and is designed to assess one's level of knowledge in the use of hematology and cytology in the diagnosis of health disorders involving exotic animal patients. The clinical cases presented were obtained from animal medical records, and each was chosen for its relevant hematology or cytology data. Although not a focus of the book, other clinical data, such as serum or plasma biochemistry profiles (presented in conventional units), imaging, and histology, are also presented with some case studies. Veterinarians, veterinary students, and veterinary technicians in clinical practice will find this additional information useful as an example of how each case was managed medically or surgically. Veterinary clinical pathologists and laboratory technicians will also find this added information beneficial in providing a complete overview of each case. Often the pathologist and laboratory technicians are exposed to only a small part of the clinical cases that they help to manage. Overall, this book is designed to test one's skills in the interpretation of laboratory data and cytology with the added benefit of providing self-assessment material for all aspects in the management of the exotic animal patient.

Results of the serum or plasma biochemistry profiles presented in these case studies were obtained using the Roche Hitachi 911 chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). Study cases that include mammalian blood cell counts were obtained using the Advia® 120 Hematology System (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). Total leukocyte counts from lower vertebrates (birds, reptiles, and fish) in the case studies were obtained by manual methods using either the direct (Natt and Herrick's method) or semidirect (phloxine B method) manual method (Campbell and Ellis, 2007).

The cases are presented in a manner that allows the reader to learn by making his or her own description of microscopic images and interpretation of the data. Following each data set, an interpretive discussion and case summaries are provided to be used by the reader for self-assessment of proficiency in interpretation of the data.

It is possible that one may have managed a case differently from what was described in the text. Each case presented in this book follows the case management as it was described in the medical records including the outcome, when known. Any differences of opinion can be used as a comparison of clinical management styles.

The clinical case studies are organized according to the animal type and diagnostic focus (either hematology or cytology):

Section 1: Mammalian Hematology Case Studies

Section 2: Avian Hematology Case Studies

Section 3: Herptile Hematology Case Studies

Section 4: Fish Hematology Case Studies

Section 5: Mammalian Cytology Case Studies

Section 6: Avian Cytology Case Studies

Section 7: Herptile Cytology Case Studies

Section 8: Fish Cytology Case Studies

The reader should note that the term “herptile” used in the title for Sections 3 and 7 is an arcane lexicon, in this case, a word used only by those who deal with reptiles and amphibians. Thus, reptiles and amphibians are collectively known as herptiles. The term likely comes from the word herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians. The term "herp," another arcane lexicon used by this group, refers to an animal that is either a reptile or an amphibian.

The following questions are to be answered by the reader while navigating through the clinical cases and are designed to guide the reader in the management of real-life cases. Many quality reference texts on avian and exotic animal medicine are available to provide the reader with in-depth information on specific aspects in the management of real-life clinical cases and aid the reader in answering these questions:

1. What is the significant historical information needed in order to assess the husbandry provided to the patient? What husbandry advice would you give to the owner of this patient?

2. What historical information is needed in order to assess the cause of the primary complaint?

3. How would one perform a physical examination on this patient?

4. How does one determine the gender in this species?

5. On the basis of the historical information and physical examination findings, what are the likely rule-outs concerning this case?

6. What, if any, diagnostic tests are needed in order to evaluate the patient and arrive at a more definitive rule-out?

7. How would one obtain a blood sample from this patient and how much blood could one safely take? What is the best restraint method in order to do this?

8. What is the best way to handle the blood once it was obtained in order to perform a complete blood cell count and serum/plasma chemistry profile?

9. How would you interpret the complete blood count?

10. How would you interpret the plasma chemistry panel?

11. If needed, how would one obtain the cytologic sample for the assessment of this patient? How would you prepare this sample for cytological evaluation? What stain would you use?

12. How would you interpret the cytologic specimen?

13. How would you restrain and position the patient for a radiographic evaluation?

14. How would you interpret the radiographs, if available?

15. On the basis of the history, physical examination, blood profile, and radiographic evaluation, what is the most likely diagnosis?

16. What would you do next in the management of this case?

17. If needed, how would you anesthetize this patient?

18. If needed, how would you surgically manage this patient? How would you perform a surgical closure in this patient? When should one remove the skin sutures?

19. What instructions would you provide to the client?

20. What is the prognosis for this patient?

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

| A/G | Albumin/globulin |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AP or ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BCS | Body condition score |

| BID | Twice daily |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CBC | Complete blood count |

| cc | Cubic centimeter |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| cm | Centimeters |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CR | Computed radiography |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| dL | Deciliter |

| DV | Dorsoventral |

| E-collar | Elizabethan collar |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| F | Fahrenheit |

| fL | Femtoliters |

| FNA | Fine-needle aspirate |

| Ft | Feet |

| g | Gram |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GGT | γ-Glutamyltranserase |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GMS | Gomori methenanime silver |

| Gy | Gray |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HCO | 3 Bicarbonate |

| IM | Intramuscularly |

| IO | Intraosseous |

| ISIS | International Species Information System |

| IU | International units |

| IV | Intravenously |

| kg | kilogram |

| LRS | Lactated Ringer's solution |

| Max | Maximum |

| MCHC | Mean cell hemoglobin concentration |

| mCi | Millicuries |

| MCV | Mean cell volume |

| M:E | Myeloid-erythroid |

| mEq | Milliequivalents |

| mg | Milligram |

| Min | Minimum |

| mL | Milliliters |

| mm | Millimeters |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| N:C | Nucleus-cytoplasm |

| N/L | Neutrophils/lymphocytes |

| nmol | Nanomole |

| Oz | Ounce |

| PCV | Packed cell volume |

| PE | Physical examination |

| pmol | Picomole |

| PO | Per os |

| ppm | Parts per million |

| ppt | Parts per thousand |

| QID | Four times daily |

| q 24 hours | Every 24 hours |

| q 72 hours | Every 72 hours |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| RDW | Red cell distribution width |

| SC | Subcutaneously |

| sp. or spp. | Species |

| Tc | Technetium |

| Tc-99m HDP | Technetium 99 high-density plasma |

| TIBC | Total iron-binding capacity |

| TID | Three times daily |

| μm | Micron |

| UIBC | Unsaturated iron-binding capacity |

| μL | Microliter |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VD | Ventral-dorsal |

| WBC | White blood cell |

Section 1

Mammalian Hematology Case Studies

1

A 6-Year-Old Otter Undergoing a Routine Physical Examination

Signalment

A 6-year-old intact North American male river otter (Lontra canadensis) was examined as part of a routine physical examination.

History

The patient was housed with two other male otters of the same age. No significant health problems had been observed in any of the otters. The otters were weighed weekly, and there had been no change in the appetite, behavior, or weight.

Physical Examination Findings

The 10 kg otter appeared healthy on physical examination (Figs. 1.1-1.4 and Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

Fig. 1.1. The North American river otter in an exhibit with his cage mate.

Other Diagnostic Information

A fecal occult blood was positive; however, no red blood cells or other abnormalities were seen on a fecal cytology.

Whole body ventral-dorsal and lateral radiographs revealed no abnormalities in the abdominal organs. The T14-L1 intervertebral disk space was narrowed with sclerotic end plates and was indicative of spondylosis deformans.

Endoscopic examination revealed evidence of fresh blood in the stomach and small punctate ulcers. Some shrimp tails remained in the stomach several hours after the last meal. The gastric mucosa was irregular, suggesting a possible infection associated with Helicobacter sp. The duodenum appeared normal. The esophagus was very long and the pylorus was open and easy to enter. Histopathologic examination of biopsies taken during the endoscopic examination revealed no abnormalities.

Fig. 1.2. The otter under anesthesia for physical examination and blood collection.

Fig. 1.3. (a and b) Blood films from an otter (Wright–Giemsa stain, 50x).

Interpretive Discussion

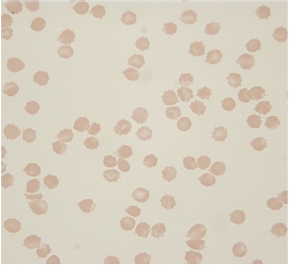

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 reveal erythrocyte abnormalities. Many of the erythrocytes are hypochromatic as indicated by extended central pallor and thin rim of hemoglobin. There are many keratocytes and schisto-cytes present. The erythrocytes (blister cells) appear to be developing vacuoles or blisters that enlarge. These blisters eventually break open to form "apple stem cells" and keratocytes. Spiculated erythrocytes (those with more than two pointed projections) are also seen. The projections fragment from the cells to form the schistocytes.

The packed cell volume (PCV), hemoglobin concentration (Hb), mean cell volume (MCV), and mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) on the hemogram are decreased, which is indicative of an iron-deficiency anemia. The appearance of microcytic, hypochromic erythrocytes on the blood film is also indicative of an iron-deficiency anemia, a condition that is nearly always caused by chronic blood loss in an adult animal. The positive fecal occult blood is suggestive of gastrointestinal blood loss in this patient; however, the two healthy otters that share his habitat also exhibited positive fecal occult blood tests. Thus, it is likely that the results of the fecal occult blood testing are false-positive owing to the meat diet of the otters. The endoscopic examination suggested the possibility of blood being lost from the upper gastrointestinal tract as would be seen with Helicobacter involvement; however, histologic examination of biopsy samples failed to confirm pathology associated with that area (Table 1.3).

Fig. 1.4. A blood film from an otter (Wright–Giemsa stain, 100x ).

Table 1.1. Hematology results.

| Day 1 | Ranges for otters at aquarium | |

| WBC (103/μL) | 7.1 | 2.7-5.3 (3.8) |

| Neutrophils (103/μL) | 4.4 | 1.6-3.9 (2.4) |

| Neutrophils (%) | 62 | 38-73 (61) |

| Lymphocytes (103/μL) | 2.4 | 0.7-1.6 (1.1) |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 34 | 16-48 (31) |

| Monocytes (103/μL) | 0.2 | 0-0.2 (0.1) |

| Monocytes (%) | 3 | 1-5 (2) |

| Eosinophils (103/μL) | 0.1 | 0-0.4 (0.2) |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1 | 1-8 (4) |

| Basophils (103/μL) | 0 | 0 |

| Basophils (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Plasma protein (g/dL) | 7.4 | 7.4-8.1 (7.7) |

| RBC (106/μL) | 11.5 | 10.9-14.6 (12.3) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.9 | 16.0-19.6 (17.0) |

| PCV (%) | 38 | 48-60 (52) |

| MCV (fL) | 33.0 | 39-45 (42) |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 26.0 | 32-34 (33) |

| Reticulocytes per microliter | 10,910-14,620 (12,673) | |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 0.1 | |

| RDW | 8.8 | 13.6-18.0 (15.1) |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 762 | 311-474 (371) |

| MPV (fL) | 5.9 | 6.0-6.9 (6.6) |

| Clumped platelets | 0 | 0 |

| Keratocytes | Moderate | 0 |

| Echinocytes | Few | 0 to few |

| Hypochromasia | Slight | 0 |

| Reactive lymphs | Few | 0 |

Table 1.2. Plasma biochemical results.

| Day 1 | Ranges for otters at aquarium | |

| Glucose (g/dL) | 109 | 91-136 (114) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 38 | 27-43 (36) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 | 0.4-0.7 (0.5) |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.6 | 2.2-4.8 (3.6) |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.9 | 8.5-9.4 (9.0) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.0 | 6.6-7.4 (7.0) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 | 2.6-3.2 (3.0) |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 4.1 | 3.6-4.2 (4.0) |

| A/G ratio | 0.7 | 0.7-0.9 (0.8) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 177 | 88-235 (175) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.1-0.2 (0.2) |

| CK (IU/L) | 149 | 148-588 (375) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 61 | 60-118 (82) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 104 | 91-127 (112) |

| AST (IU/L) | 122 | 88-174(125) |

| GGT (IU/L) | 9 | 7-14(10) |

| Sodium (mg/dL) | 147 | 143-149 (146) |

| Potassium (mg/dL) | 3.7 | 3.7-4.0 (3.9) |

| Chloride (mg/dL) | 114 | 107-115 (112) |

| Bicarbonate (mg/dL) | 20.8 | 17-25 (21) |

| Anion gap | 15 | 10-20 (16) |

| Calculated osmolality | 300 | 291-303 (297) |

| Lipemia (mg/dL) | 9 | – |

| Hemolysis (mg/dL) | 9 | – |

| Icterus (mg/dL) | 0 | – |

Table 1.3. Plasma iron profile results.

| Day 1 | Ranges for otters at aquarium | |

| Iron (μig/dL) | 35 | 112-160 (135) |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | 434 | 286-409 (320) |

| Saturation (%) | 8 | 27-58 (44) |

| UIBC (μ g/dL) | 399 | 116-297 (186) |

Variability in the normal serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and percent saturation of trans-ferrin occurs among mammalian species; however, in general, healthy animals have an average serum iron concentration of 100 μxg/dL, a TIBC of 300 μxg/dL, and transferrin saturation of 33%. Using these values, this otter patient has a confirmed iron deficiency based on reduced serum iron concentration and transferrin saturation with an increased TIBC.

The platelet count is greater than expected. This is a common finding associated with iron-deficiency anemia in other mammalian species. The exact cause of this is unknown.

The otter had a mild leukocytosis, mature neu-trophilia, and lymphocytosis, which are suggestive of a physiological leukocytosis. This is not surprising owing to the nature of capture and delivery of a chemical restraint needed in order to obtain the blood sample.

Summary

The otter underwent a 4-month treatment for a presumed chronic blood loss anemia resulting in the loss of iron from the gastrointestinal tract in association with a Helicobacter sp. infection. He was also treated with injectable supplemental iron. Because the otter never appeared weak or ill from his anemia, a reevaluation examination was performed 4 months following the initial examination. The erythrocyte parameters had returned to normal by that time.

2

A 10-Year-Old Ferret with Lethargy and Anorexia

Signalment

A 10-year-old castrated male Fitch ferret (Mustela putorius furo) was presented for anorexia and lethargy (Fig. 2.1).

History

The ferret recently exhibited bouts of intermittent melena. The ferret is housed with two other ferrets that appear healthy. Other pets in the household include two dogs and two cats. The client lives on a small farm where a small number of livestock (cattle and chickens) are kept. The ferrets are fed a commercial kibbled diet.

Physical Examination Findings

A geriatric ferret was 10% dehydrated and was moderately lethargic. A small amount of watery discharge was noted from his left eye. There was also a significant amount of debris in both ears that contained a mixed yeast and bacterial infection based on cytological examination. See Figures 2.2-2.5 and Tables 2.1 and 2.2.

Interpretive Discussion

In Fig. 2.2, the dark tarry stool is representative of melena. Figure 2.3 represents ear mites (Otodectes). Figure 2.4 shows the Wright–Giemsa stained blood film, which reveals numerous echinocytes and a schis-tocyte. An erythrocyte in the center as well as a few others appears to contain a pale structure, suggestive of Heinz bodies. Figure 2.5 shows staining of the blood with a stain used to detect reticulocytes and reveals blue structures within the erythrocytes, indicative of Heinz bodies.

On day 1, the ferret appears to be exhibiting a stress leukogram; however, considering the geriatric status of the ferret, it is also likely that the neutrophils/ lymphocytes ratio has changed with age, resulting in decreased lymphocytes and increased neutrophils compared to younger ferrets. The ferret has a significant anemia based on the low PCV, RBC, and hemoglobin concentration. The cause of the anemia is likely in part related to blood loss in the gastrointestinal tract as indicated by melena. The refractometric plasma protein is low, which supports blood loss; however, this finding is not supported by the normal protein or perhaps elevated value found in the biochemical profile. Because the ferret appears clinically dehydrated, the anemia may actually be worse than it appears and the red cell indices and total protein values would expect to decrease with fluid replacement therapy. The anemia may also be related in part to a hemolytic anemia associated with Heinz body formation in the erythrocytes in which a moderate number of large Heinz bodies and a few small Heinz bodies were reported on the hemogram. At this time, the anemia appears to be poorly regenerative as indicated by the lack of a significant polychromasia and reticulocyte count. The platelet count is low owing to either excessive peripheral utilization of platelets associated with gastrointestinal hemorrhage or perhaps as an analytic artifact associated with clumping of platelets as indicated by the interpretation of the blood film. The presence of echinocytes is typically an artifactual finding.

The plasma biochemical profile on day 1 indicates a possible hyperproteinemia with a hyperglobulinemia suggestive of an immune response based on the first set of reference values but not supported by the second set of reference values.

The hemogram on day 6 indicates no significant change in the leukogram; however, there is a marked improvement to the erythrocyte parameters. The ferret is exhibiting a significant regenerative response to his erythrocytes, platelets, and refractometric total protein. He is no longer anemic and appears to be recovering from a blood loss anemia. The unexplained presence of Heinz bodies in this case has disappeared. Heinz bodies are caused by oxidative damage to hemoglobin. A common cause for this condition in domestic cats is inges-tion of onions or onion products. Other plants, such as garlic, Brassica, and red maple (Acer rubrum) leaves, may also cause Heinz body formation. Drugs such as acetaminophen, phenazopyridine, phenothiazine, and propylene glycol, to name a few, will also cause Heinz body formation. No history of exposure to any of these materials was revealed in this case. Heinz body formation can occur without exposure to oxidant chemicals or drugs with medical conditions, such as lymphoma, diabetes mellitus, and hyperthyroidism.

Fig. 2.1. The 10-year-old ferret during physical examination that presented with anorexia and lethargy.

Fig. 2.2. The gross appearance of the ferret's feces.

Fig. 2.3. A microscopic image of the material collected from the ferret's ear.

Fig. 2.4. A microscopic image of the erythrocytes on the blood film from the ferret (Wright–Giemsa stain, 100 x).

Fig. 2.5. A microscopic image of the erythrocytes on the blood film from the ferret (methylene blue stain, 100 x)

Table 2.1. Hematology results.

aColorado State University reference ranges.

bFox (1988).

cCarpenter (2005).

Table 2.2. Plasma biochemical results.

aColorado State University reference ranges.

bFox (1988).

cCarpenter (2005).

Summary

The ferret's overall condition improved after 5 days of treatment for Helicobacter-induced gastrointestinal ulcers and hemorrhage, which continued for a total of21 days. This treatment consisted of amoxicillin (20 mg/kg PO BID), doxycycline (5 mg/kg PO BID), omeprazole (0.7 mg/kg PO daily), and sucralfate (25 mg/kg pO every 8 hours). He was also successfully treated for an ear mite infestation using ivermectin (0.3 mg/kg) subcutaneously once every 10 days for three treatments.

3

A 6-Year-Old Ferret with Anorexia and Lethargy

Signalment

A 6-year-old female ferret (Mustela putorius furo) was presented for anorexia and lethargy.

History

This adult female ferret had a 2-day history of anorexia. The client had not observed her eating or drinking during this period and reported that the ferret has been sleeping more than usual. The owner did observe that although her stool production was less than normal, it appeared dark. During the past year, the ferret has been given oral melatonin for suspected adrenal disease. The ferret was normally fed a diet of kibbled ferret food.

Physical Examination Findings

The ferret was thin (body score of 3/9) and weighed 500 g. She was lethargic and at least 10% dehydrated. She was weak and reluctant to move. Her body temperature was 98°F and she had tachypnea. Black tarry stools were found adherent to the hair around the anus. A large ulcer was found during examination of the oral cavity. See Figures 3.1 and 3.2 and Tables 3.1 and 3.2.

Other Diagnostic Findings

A radiographic evaluation of the ferret (Fig. 3.3) indicated a diffuse, unstructured interstitial to alveolarpat-tern in the caudal dorsal lungs. Because the radiographs were not centered over the thorax, specific thoracic radiographs were recommended for further evaluation. The cardiac silhouette appears to be within normal limits and the pulmonary vasculature appears to be within normal limits. The serosal detail of the abdomen is poor. There is very little falciform fat (back fat), suggesting an overly thin animal. What can be visualized in the abdomen appears to be otherwise normal. On the lateral image, the abdomen appears mildly pendulous. There is a large spleen, although this is typical for a ferret; however, splenomegaly cannot be entirely ruled out. The findings of the thorax and lungs could be indicative of hematogenous pneumonia in the caudal dorsal lungs. Alternatively, diffuse neoplasia cannot be entirely ruled out. Repeat imaging with computed radiography would be recommended to try to further evaluate these caudal dorsal lung lobes. The appearance of the loss of serosal detail in the abdomen could be the result of poor body condition score, although peritoneal effusion or carci-nomatosis cannot be entirely ruled out. The remainder of the abdomen is unremarkable. An ultrasound examination was recommended, but declined by the client owing to the cost of the procedure.

Interpretive Discussion

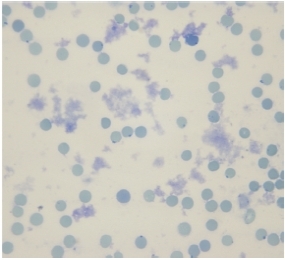

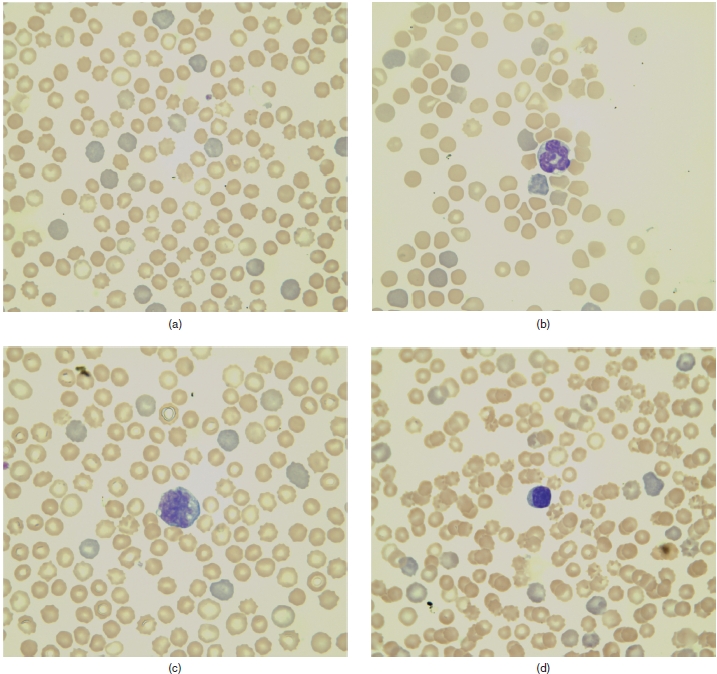

Figure 3.2a shows a marked number of polychro-matophilic erythrocytes and echinocytes. Figure 3.2b shows a toxic neutrophil among erythrocytes, exhibiting significant polychromasia. Figure 3.2c shows a monocyte among erythrocytes, exhibiting significant poly-chromasia and many echinocytes. Figure 3.2d shows a lymphocyte with a moderate amount of dark blue cytoplasm, indicating a reactive lymphocyte as well as a significant polychromasia and many echinocytes.

In general, the hematology of ferrets resembles that of domestic carnivores. In this case, the ferret has a marked regenerative anemia based on the marked poly-chromasia on the blood film, presence of nucleated erythrocytes, and marked number of reticulocytes. The cause of the anemia is likely to be associated with blood loss as indicated by the low total protein and a low platelet count that indicates excessive consumption of platelets. The blood loss is likely from gastrointestinal hemorrhage as indicated by the presence of melena on the physical examination.

Fig. 3.1. The 6-year-old ferret during physical examination that presented with anorexia and lethargy. (a) Oral cavity examination reveals an ulcer (arrow). (b) The Ferret in left lateral recumbency (the tail is on the left side of image and legs are on the right side). Melena seen on perianal region.

Fig. 3.2. (a–d) Microscopic images from the blood film (Wright–Giemsa stain, 100x).

Table 3.1. Hematology results.

aColorado State University reference ranges.

bFox (1988).

cCarpenter (2005).

Table 3.2. Plasma biochemical results.

aColorado State University reference ranges.

bFox (1988).

cCarpenter (2005).

Neutrophil concentrations are generally higher than lymphocyte concentrations in normal ferrets and they tend to increase in concentration, while lymphocytes decrease in concentration with increasing age. The total leukocyte count of healthy ferrets can be as low as 3,000/|xL; therefore, ferrets are unable to develop a marked leukocytosis with inflammatory disease, and concentrations greater than 20,000/|xL are unusual and a left shift is rare. In this case, the ferret has a leukopenia with slightly toxic neutrophils and a left shift indicative of a degenerative left shift. She has also a severe lymphopenia.

The increased serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration can be associated with dehydration, renal failure, or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The nonexistent creatinine supports the idea of gastrointestinal hemorrhage; however, one must consider that in normal and azotemic ferrets, the plasma creatinine concentration is lower than that in dogs and cats. The mean plasma crea–tinine concentration of healthy ferrets is 0.4-0.6 mg/dL with a range of 0.2-0.9 mg/dL. As a result, a moderate increase in the plasma creatinine concentration (i.e., 1-2 mg/dL) in a ferret is significant and suggestive of renal disease. This, however, is not an issue in this case.

Evaluation of the liver in ferrets by laboratory testing is the same as that for those in dogs and cats. The plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, which appears elevated in this case, is a sensitive and specific test for hepatocellular disease in ferrets. Ferrets with hepatocellular disease commonly have increased aspar-tate aminotransferase (AST) activity as well. Those with cholestasis likely have increased plasma alkaline phos-phatase and 7 -glutamyl transferase (GGT) activities. Ferrets rarely become icteric or have plasma bilirubin concentrations greater than 2.0 mg/dL, even when hep-atobiliary disease is severe. In this case, the ferret likely has hepatocellular disease.

The causes of hypoproteinemia in ferrets are the same as those in dogs and cats. In this case, it is likely associated with significant blood loss from gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The prognosis for survival in this ferret based on the physical examination, hemogram, and plasma biochemical profile is poor.

Fig. 3.3. The radiograph of dorsoventral position (right image) and left lateral position (left image).

Summary

The ferret was immediately transferred to the critical care unit for intravenous fluid therapy, correction of hypothermia, and treatment for Helicobacter-induced gastrointestinal ulcers. The treatment plan included doxycy-cline (2.5 mg PO BID), amoxicillin (11 mg PO TID), sucralfate (125 mg PO QID), and two beads from a 20 mg omeprazole capsule (PO daily). The ferret died within 12 hours following presentation. Gross necropsy findings revealed a large perforated ulcer at the gastric pylorus, associated with a marked amount of hemorrhage.