Contents

This edition first published 2011, © Blackwell Publishing Ltd

BMJ Books is an imprint of BMJ Publishing Group Limited, used under licence by Blackwell Publishing which was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing programme has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered office: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting a specific method, diagnosis, or treatment by physicians for any particular patient. The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. Readers should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. No warranty may be created or extended by any promotional statements for this work. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any damages arising herefrom.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ABC of sexually transmitted infections. – Sixth Edition / edited by Karen Rogstad, Department of Genitourinary Medicine, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, UK.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9816-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2. Communicable diseases. I. Rogstad, Karen, editor.

[DNLM: 1. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. WC 140]

RA644.V4A24 2011

614.5′47 – dc22

2010047401

To Luke and Annabelle

Preface

It is over a quarter of a century since the first edition of ABC of Sexually Transmitted Infections was published. In that time there have been major changes in sexually transmitted infections. AIDS in 1984 was only just being recognised, but then subsequently became a major global epidemic. Initially there was no effective treatment and death was inevitable for most sufferers; now it is treatable, although the infection cannot be eliminated. While there is still no universal access to treatment, significant inroads have been made in treatment provision in resource-poor nations. Syphilis in the western world has shown a decline over the 25 years but there has been a recent resurgence. Lymphogranuloma venereum was a tropical STI but is now endemic in some communities of men who have sex with men. Gonorrhoea continues its relentless progress in developing resistance to antibiotics. STI diagnosis has changed from being labour intensive, requiring laboratory diagnosis by highly trained staff, to more sensitive tests that can be performed by a broader range of providers in the community, including the patient themselves.

The way sexual health care is provided has also shown a dramatic change, with much more community testing and treatment, and the integration of STI and contraceptive care. In addition, there has been an increased awareness of the need to address child protection issues for some sexually active adolescents. Finally, the internet has revolutionised how patients access information and services, and how professionals learn.

This new edition has also evolved over the years to reflect these changes, moving from the excellent 1984 edition written by Professor Michael Adler to a book with international authorship which brings together all the developments listed above to provide a resource for all those providing sexual health services, and those who wish to learn more about the subject. It is hoped that traditional and new sexual health care providers, as well as medical, nursing and pharmacy students, throughout the world will be able to utilise the information in this edition to enhance their own knowledge and thus improve patient care and STI prevention. I would like to acknowledge the expertise and work of the editors of the previous edition, which has formed the basis for this one – Michael Adler, Frances Cowan, Patrick French, Helen Mitchell, and John Richens.

Karen E Rogstad

Contributors

Sarah Alexander

Clinical Scientist, Sexually Transmitted Bacteria Reference Laboratory, Health Protection Agency, London, UK

Monique Andersson

Specialist Registrar in Virology and Genitourinary Medicine, Health Protection Agency Regional Laboratory South West; Bristol Sexual Health Clinic, Bristol, UK

Gill Bell

Nurse Consultant and Sexual Health Adviser, Genitourinary Medicine, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

Alison Bigrigg

Director, The Sandyford Initiative, Glasgow, UK

Aparna Briggs

Specialist Registrar in Genitourinary Medicine, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

M Gary Brook

Clinical Lead GUM/HIV, North West London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Chris Bunker

Consultant Dermatologist, University College and Chelsea & Westminster Hospital; Professor of Dermatology, University College, London, UK

Elizabeth Carlin

Consultant Physician in Genitourinary Medicine, Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Nottinghamshire, UK

Frances Cowan

Senior Lecturer and Honorary Consultant, University College London, London, UK

David Daniels

Consultant in Sexual Health and HIV, West Middlesex University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Isleworth, UK

Sarah Edwards

Consultant GU Physician, Suffolk Community Health, West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St Edmunds, UK

Claudia Estcourt

Reader in Sexual Health and HIV, Queen Mary University of London, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK

Christopher K Fairley

Chair of Sexual Health Unit, University of Melbourne; Director, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

Kevin A Fenton

Director, National Centers for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Coordinating Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA

Paul A Fox

Consultant in Sexual Health and HIV, Ealing Hospital; Honorary Senior Lecturer, Imperial College School of Medicine, London, UK

Patrick French

Consultant Physician, Camden Primary Care Trust, London, UK; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University College London, London, UK

Keerti Gedela

Specialist Registrar GUM/HIV, West Middlesex University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Isleworth, UK

Nadi Gupta

Specialist Registrar in Genitourinary Medicine, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

Phillip Hay

Reader in HIV/GU Medicine, Centre for Infection, St George’s, University of London, London, UK

Ashini Jayasuriya

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Nottingham University Hospitals, Nottingham, UK

Vincent Lee

Consultant, Manchester Centre for Sexual Health, Manchester, UK

David A Lewis

Head of the Sexually Transmitted Infections Reference Centre, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, South Africa

Pat Munday

Consultant Genitourinary Physician, Watford Sexual Health Centre; West Herts Hospitals NHS Trust, Watford, UK

Rak Nandwani

Acting Director, The Sandyford Initiative, Glasgow, UK

Raj Patel

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Department of GU Medicine, Royal South Hants Hospital, Southampton, UK

Katrina Perez

Specialist Registrar, Manchester Centre for Sexual Health, Manchester, UK

Anna Pryce

Specialist Registrar in Genitourinary Medicine, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

Cecilia Priestley

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Dorchester, UK

John Richens

Clinical Lecturer, Centre for Sexual Health and HIV Research, University College London, London, UK

Angela J Robinson

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Mortimer Market Centre, London, UK

Karen E Rogstad

Consultant Physician, Department of Sexual Health and HIV, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

Jonathan D C Ross

Professor of Sexual Health and HIV, Whittall Street Clinic; Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Birmingham), Birmingham, UK

John Saunders

Specialist Registrar, Queen Mary University of London, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK

Ian Williams

Senior Lecturer, Centre for Sexual Health & HIV Research, The Royal Free and University College London Medical School; Honorary Consultant Physician, UCL Research Department of Infection and Population Health, London, UK

Janet Wilson

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Department of Genitourinary Medicine, The General Infirmary at Leeds, Leeds, UK

Clare L N Woodward

Specialist Registrar GUM, Department of Genitourinary Medicine, Mortimer Market Centre, London, UK

CHAPTER 1

Sexually Transmitted Infections: Why are they Important?

OVERVIEW

What are sexually transmitted infections?

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are infections that are spread primarily through person-to-person sexual contact. There are more than 30 different sexually transmissible bacteria, viruses, and parasites (). Several, in particular HIV and syphilis, can also be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy and childbirth, and through blood products and tissue transfer.

In general, the viral STIs (including sexually transmitted HIV and hepatitis A, B, and C) are more prevalent, often causing lifelong infections, frequently asymptomatic in their early phases, and may result in serious long-term sequelae including chronic morbidity or even mortality. In contrast, the bacterial and protozoal STIs are generally curable, and often asymptomatic. The causative organisms may cause a spectrum of genitourinary symptoms, including urethral discharge, genital ulceration, and vaginal discharge with or without vulval irritation.

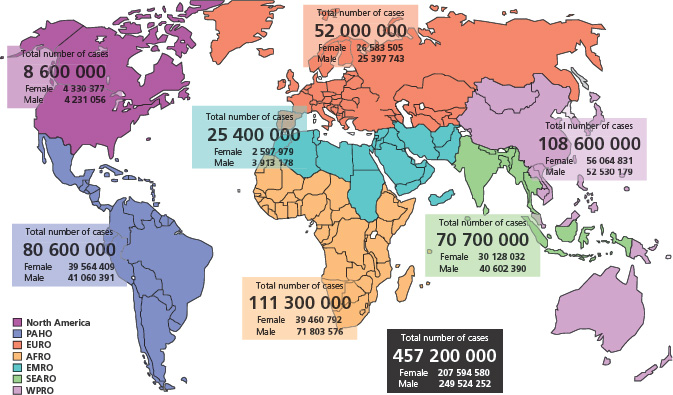

STIs are among the most commonly diagnosed infectious diseases in many parts of the world. More than a million people acquire HIV or another STI every day, and there are 450 million new cases of curable STIs occurring in adults each year. There is marked variation in the prevalence and incidence of infections throughout the world, and even within countries ( and ).

Why are STIs important?

Being diagnosed with an STI can have a tremendous physical, emotional, and psychological toll on individuals. Symptoms are unpleasant and may cause considerable pain, and have systemic complications. HIV and hepatitis B and C may have an aggressive course leading to lifelong morbidity and death. Some human papillomavirus (HPV) types are a cause of cervical, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer (). Chlamydia and gonorrhoea are both the most serious, and also most preventable, threats to women’s fertility worldwide. The World Bank estimated that STIs (excluding HIV) were the second most common cause of healthy life lost after maternal morbidity in 15- to 44-year-old women ().

Effects on pregnancy, neonates, and children

STIs can lead to miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, and in utero death. They can also cause neonatal illness and death, and long-term sequelae. The consequences of congenital herpes and HIV are well recognised in developed nations. However, the magnitude of the congenital syphilis burden, globally, rivals that of HIV infection in neonates yet receives little attention. Congenital syphilis results in serious adverse outcomes in up to 80% of cases and is estimated to affect over 1 million pregnancies annually.

Effects on partners

STIs are also important to sexual partners, who may have asymptomatic infection. Partner notification is a key strategy for identifying and treating sexual partners for most STIs (see Chapter 2). The diagnosis of an acute STI may indicate that a partnership is non-monogamous, with negative impacts on relationships. For some couples who are discordant for infections such as HIV or herpes, there are long-term implications such as whether to have unprotected sex and psychological issues.

Stigma

The stigma and fear of STIs cannot be over-emphasised. There is significant psychological morbidity associated with being diagnosed with an STI which ranges from mild distress to severe anxiety and depression. Stigma can result in people living with HIV and other STIs being rejected, shunned, and discriminated against by partners, family, and community, and being victims of physical violence. Stigma not only makes it more difficult for people trying to come to terms with and manage their illness, but it also interferes with attempts to fight the disease more generally. On a national level, stigma can deter governments from taking fast, effective action against STI epidemics.

Main sexually transmitted pathogens and the diseases they cause.

Source: World Health Organization, 2007.

| Pathogen | Clinical manifestations and other associated diseases |

| Bacterial infections | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoea | GONORRHOEA Men: urethral discharge (urethritis), epididymitis, orchitis, infertility. Women: cervicitis, endometritis, salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, preterm rupture of membranes, peri-hepatitis. Both sexes: proctitis, pharyngitis, disseminated gonococcal infection. Neonates: conjunctivitis, corneal scarring and blindness |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | CHLAMYDIAL INFECTION Men: urethral discharge (urethritis), epididymitis, orchitis, infertility. Women: cervicitis, endometritis, salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, preterm rupture of membranes, peri-hepatitis; commonly asymptomatic. Both sexes: proctitis, pharyngitis, Reiter’s syndrome. Neonates: conjunctivitis, pneumonia |

| Chlamydia trachomatis (strains L1–L3) | LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM Both sexes: ulcer, inguinal swelling (bubo), proctitis |

| Treponema pallidum | SYPHILIS Both sexes: primary ulcer (chancre) with local adenopathy, skin rashes, condylomata lata; bone, cardiovascular, and neurological damage. Women: pregnancy wastage (abortion, stillbirth), premature delivery. Neonates: stillbirth, congenital syphilis |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | CHANCROID Both sexes: painful genital ulcers; may be accompanied by bubo |

| Klebsiella (Calymmatobacterium) granulomatis | GRANULOMA INGUINALE (DONOVANOSIS) Both sexes: nodular swellings and ulcerative lesions of the inguinal and anogenital areas |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | Men: urethral discharge (nongonococcal urethritis). Women: bacterial vaginosis, probably pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Ureaplasma urealyticum | Men: urethral discharge (nongonococcal urethritis). Women: bacterial vaginosis, probably pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Viral infections | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME (AIDS) Both sexes: HIV-related disease, AIDS |

| Herpes simplex virus type 2 Herpes simplex virus type 1 (less commonly) | GENITAL HERPES Both sexes: anogenital vesicular lesions and ulcerations. Neonates: neonatal herpes (often fatal) |

| Human papillomavirus | GENITAL WARTS Men: penile and anal warts; carcinoma of the penis. Women: vulval, anal and cervical warts, cervical carcinoma, vulval carcinoma, anal carcinoma. Neonates: laryngeal papilloma |

| Hepatitis B virus | VIRAL HEPATITIS Both sexes: acute hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, liver cancer |

| Cytomegalovirus | CYTOMEGALOVIRUS INFECTION Both sexes: subclinical or nonspecific fever, diffuse lymph node swelling, liver disease, etc. |

| Molluscum contagiosum virus | MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM Both sexes: genital or generalized umbilicated, firm skin nodules |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpes virus (human herpes virus type 8) | KAPOSI’S SARCOMA Both sexes: aggressive type of cancer in immunosuppressed persons |

| Protozoal infections | |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | TRICHOMONIASIS Men: urethral discharge (nongonococcal urethritis); often asymptomatic. Women: vaginosis with profuse, frothy vaginal discharge; preterm birth, low birth weight babies. Neonates: low birth weight |

| Fungal infections | |

| Candida albicans | CANDIDIASIS Men: superficial infection of the glans penis. Women: vulvo-vaginitis with thick curd-like vaginal discharge, vulval itching or burning |

| Parasitic infections | |

| Phthirus pubis | PUBIC LICE INFESTATION |

| Sarcoptes scabiei | SCABIES |

Economic burden

STIs can have significant economic impacts on the individual and community. Even where treatment for STIs is free or low cost, individuals may pay for care in the private sector, or access traditional healers, because of stigma. Aditionally, there are opportunity costs incurred through missing work, travelling to the clinic, or purchasing treatment and returning for follow-up.

The global economic impact of STIs is staggering. However, treatment costs for STIs vary tremendously between countries and are influenced a range of factors. Reproductive ill-health (death and disability related to pregnancy, childbirth, STIs, HIV, and reproductive cancers) is thought to account for 5–15% of global disease burden. In developing countries they account for 17% of economic losses caused by ill-health and rank among the top 10 reasons for health care visits. In the United States, STIs cost $16 billion annually to the health care system ( and ). Care for the complications of STIs accounts for a large proportion of tertiary health care in terms of screening and treatment of cervical cancer, management of liver disease, investigation of infertility, care for perinatal morbidity, childhood blindness, and chronic pelvic pain. Preventing a single HIV transmission would save £0.5–1 million in health benefits and costs.

Global incidence of selected STIs, 2005. Source: World Health Organization, 2009.

Estimated prevalence and annual incidence of curable STI by region.

Source: World Health Organization, 2001.

The economic impact in resource poor settings is even greater where the majority of curable STIs and HIV occur, particularly South and South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Box 1.1). Delays in the diagnosis and treatment increase complications and mortality with a substantial economic impact. In countries with high HIV prevalence, morbidity and mortality from HIV has led to important changes in average household composition and population structure.

Box 1.1 Factors influencing costs and cost effectiveness of STI treatment and care

Source: adapted from Bertozzi & Opuni (2008).

Major sequelae of STIs.

Top 10 causes of healthy life lost in young adults aged 15–44 years.

Average (standard deviation) of estimated cost per unit output, by disease or syndrome and by type of output, 2001 US$.

Source: Aral et al. (2005).

Estimated annual burden and cost of STI in the United States.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

| STI | Estimated annual cases | Estimated annual direct cost (millions) US dollars |

| Chlamydia | 2.8 million | $624 |

| Gonorrhoea | 718,000 | $173 |

| Syphilis | 70,000 | $22 |

| Hepatitis B | 82,000 | $42 |

| Genital herpes | 1.6 million | $985 |

| Trichomoniasis | 7.4 million | $179 |

| HPV | 6.2 million | $5,200 |

| HIV | 56,300 | $81,000 |

| Total | 18.9 million | $15.3 billion |

Size of the problem

In 2008 there were an estimated 33.4 million people living with HIV worldwide, 2.7 million new HIV infections, and 2 million HIV-related deaths ( and ; ). Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region most heavily affected by HIV, accounting for 67% of all people living with HIV and for 70% of AIDS deaths in 2008. However, some of the most worrying increases in new infections are now occurring in populous countries in other regions, such as Indonesia, the Russian Federation, and various high-income countries. The rate of new HIV infections has fallen in several countries, including 14 of 17 African countries, where the percentage of young pregnant women (15–24 years) living with HIV has declined since 2000. As treatment access has increased over the last 10 years, the annual number of AIDS deaths has fallen. Globally, the percentage of women among people living with HIV has remained stable (at 50%) for several years, although women’s share of infections is increasing in several countries.

Prevalence of STIs among 14- to 19-year-old US females, NHANES, 2003–2004.

Source: adapted from Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics 2009; 124(6):1505–12.

Adults and children estimated to be living with HIV, 2008. Source: UNAIDS, 2009.

Global prevalence of Adult HIV prevalence, 2008. Source: UNAIDS, 2009.

Number of new infections in 2005 (millions) in adult males and females between the ages of 15 and 49 (see also ).

Gonorrrhoea and Chlamydia

There is tremendous global geographic variation in the rates of the more common bacterial STI (). Gonorrhoea rates fell in westernised counties in the 1980s as a result of the AIDs epidemic leading to safer sexual practices ( and ). There was a subsequent increase in recent years in many European countries, but in the United Kingdom this has now stabilised and is starting to fall ( and ). Chlamydia rates have increased steadily in Europe and North America since 1996, with prevalence rates of 10% in young people. Because of the development of more sensitive tests, and screening programmes, it is not possible to determine whether this is a true increase in number of cases or not.

Genital herpes and genital warts

The total number of people aged 15–49 years who were living with herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection worldwide in 2003 was estimated to be 536 million, with the total number of people who were newly infected with HSV-2 in 2003 estimated to be 23.6 million. HSV-2 prevalence is highest in Africa and the Americas, and lowest in Asia. HSV-2 and -1 prevalence, overall and by age, varies markedly by country, regions within countries, and population subgroup (). Age-specific HSV-2 prevalence is usually higher in women than men and in populations with higher risk sexual behaviour. The number infected increases with age. Genital warts remain a major problem, but dramatic declines have been shown in parts of Australia following the introduction of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in that country.

Regional estimates of the prevalence of the herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among females, in 2003.

Source: Looker KJ, Garnett GP, Schmid GP. An estimate of the global prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(10):805–12, A.

Cases of uncomplicated gonorrhoea seen in genitourinary medicine clinics by sex and male sexual orientation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1998–2008. Source: adapted from Health Protection Agency (), Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre. Data from KC60 statutory returns.

Diagnoses of uncomplicated genital chlamydial infection in genitourinary medicine clinics by sex and age group in the United Kingdom, 1999–2008. Source: adapted from Health Protection Agency (), Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre. Data from KC60 statutory returns and ISD(D)5 data.

All diagnoses and workload at genitourinary medicine clinics by country, 1990–2005. Source: adapted from Health Protection Agency (), Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre. Data from KC60 statutory returns and ISD(D)5 data ().

Syphilis and lymphogranuloma venereum

Despite the existence of simple tests, effective prevention measures, and cheap treatment options, syphilis remains a major global problem, with an estimated 10.6 million people becoming infected every year (). Although syphilis remains relatively rare in developed countries, there has been a recent resurgence in rates of disease, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM), and more recently among heterosexuals. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), until recently considered a tropical STI, is now a significant problem in MSM in the United Kingdom and other westernised countries, and has a strong association with HIV.

New diagnoses of selected STIs in men who have sex with men, England and Wales, 1998–2007. Source: adapted from Health Protection Agency (), Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre ().

Cases of infectious syphilis (primary and secondary) seen in genitourinary medicine clinics by sex and male sexual orientation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1999–2008. Source: adapted from Health Protection Agency (), Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre.

Who gets STIs and why?

Globally, the highest rates of STIs occur among 20- to 24-year-olds, followed by 15- to 19-year-olds (). One in 20 young people is believed to contract a bacterial STI in any given year. In the United States, up to 1 in 4 adolescent females have an STI. In the United Kingdom, 16- to 24-year-olds are the age group most at risk of being diagnosed with an STI, accounting for 65% of all chlamydial infections, 55% of genital warts, and 52% of gonorrhoea. MSM represent the majority of primary and secondary syphilis cases and racial and ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of bacterial STIs including chlamydia and gonorrhoea.

At the individual level, biological and behavioural factors influence the risk of acquiring or transmitting an STI, including age, presence of other STIs, circumcision status, engaging in unprotected sex, riskier sex practices, and number of partners (). Synergy between STIs and HIV affect risk. STIs are associated with increased risk of HIV transmission, at a population and individual level, and STIs increase the risk of both acquiring and transmitting HIV (Box 1.2). The British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles shows an increase in many risk factors including number of partners, concurrency rates, same sex partnerships, and anal sex ( and ). Additionally, the age of first sex has decreased in the UK, with 25% of teenagers sexually active by their sixteenth birthday. These behavioral changes may explain some of the increasing STIs seen in the UK over the past two decades.

Percentage of STIs diagnosed among young people (16–24 years), United Kingdom, 2008.

Percentage distribution of heterosexual partners in lifetime by sex, 1990 and 2000. Source: adapted from National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, 2000.

Box 1.2 Role of STIs in the acquisition of HIV

There is a strong association with number of lifetime and recent sexual partners, the rate of new sex partner acquisition, and partner concurrency (having overlapping sexual partnerships). Other factors include the type of partnership, the gender power dynamics within it, intimate partner violence, and cultural pressures.

Changes in behaviour over time. Source: adapted from National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, 2000.

Changes in behaviour over time. Source: adapted from National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, 2000.

Sexual networks

Sexual networks are groups of individuals who are directly or indirectly sexually connected to each other. The patterns of linkages between individuals in the network influence the paths through which STIs may be transmitted. Sexual networks can be affected by community norms about sexual behaviour, social upheaval, travel, and migratory patterns. The location of individuals within a network can be more important than their personal sexual behaviour, because it can increase the prevalence of infection in those to whom they are directly sexually connected. The existence of sexual bridges also influences the distribution of STIs in a population. The importance of networks is shown with the rapid spread of HIV in the early 1980s, outbreaks of LGV and syphilis among HIV-positive MSM in many western European countries, and the hyperendemic levels of bacterial STIs within racial and ethnic groups in developed country settings. In the latter, assortative sexual mixing by race/ethnicity combined with failure to break transmission chains within networks are key drivers for the persistent racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States and United Kingdom.

Societal burden and impact

Political conflict, economic and social disruption, and migration lead to the breakdown of existing social structures and the formation of new ones. In fast-growing cities, factors including high incarceration rates, the higher numbers of men than women, the lack of employment for women, and the social disruption resulting from large streams of migration are associated with increases in sex work.

Other population-level factors relevant to STI transmission include the availability and cost of prevention services (e.g. sex education, condoms, or treatment clinics), legislation regarding commercial sex workers, and educational and occupational opportunities for women. National HIV/STI prevention policies driven by religious or conservative social mores, can negatively impact on prevention programmes such as provision of free condoms.

Prevention

There are many actions individuals can take to protect themselves from STIs and their consequences: abstain from sex; be in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner; consistent and correct use of the male condom; getting tested and treated for STIs; and receiving hepatitis B and HPV immunizations. For individuals with chronic viral conditions such as HIV, HSV, or hepatitis B and C, early diagnosis, counselling, and referral for treatment can reduce the risk of onward transmission to sexual partners.

Conclusions

Sexually transmitted infections are a major individual, societal, and public health concern. Their social, health, and economic costs are substantial and affect the lives and well-being of individuals, relationships, communities, and societies with disproportionate impacts among the young, socioeconomically deprived, or those with high levels of risk behaviours and their partners. Understanding the nature and determinants of this burden are the first steps in articulating their importance to the public and policy makers, and justifying scarce health resources for their management.

Further reading

Aral SO, Padian NS, Holmes KK. Advances in multilevel approaches to understanding the epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV: an overview. J Infect Dis 2005; 191(Suppl 1): S1–6.

Bertozzi SM, Opuni M. An economic perspective on sexually transmitted infections including HIV in developing countries. In Holmes KI, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, Cohen MS, Watts DH (eds). Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 4th edn. McGraw Hill, New York, 2008, pp. 13–26.

Fenton KA, Breban R, Vardavas R, Okano JT, Martin T, Aral S, Blower S. Infectious syphilis in high-income settings in the 21st century. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8(4):244–53.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO) 2009. AIDS epidemic update: November 2009. Available at .

Schmid G. Global incidence and prevalence of four curable sexually transmitted infections (STIs): New Estimates from WHO. Presentation at the 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting. March 2009. Bangkok, Thailand. Available at . Last accessed 19 January 2010.

World Health Organization. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Curable STIs. WHO, Geneva, 2001 (WHO/CDS/CDR/EDC/2001.10).