Contents

This edition first published 2011 © 2011 by Omar Faiz, Simon Blackburn and David Moffat

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered office: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030–5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting a specific method, diagnosis, or treatment by physicians for any particular patient. The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. Readers should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. No warranty may be created or extended by any promotional statements for this work. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any damages arising herefrom.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Faiz, Omar.

Anatomy at a glance/Omar Faiz, Simon Blackburn, David Moffat.–3rd ed.

p.; cm.–(At a glance)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4443-3609-2

1. Human anatomy-Outlines, syllabi, etc. I. Blackburn, Simon, 1979- II. Moffat, D. B. (David

Burns) III. Title. IV. Series: At a glance series (Oxford, England)

[DNLM: 1. Anatomy. QS 4]

QM31.F33 2011

611-dc22

2010029199

Preface to the first edition

The study of anatomy has changed enormously in the last few decades. No longer do medical students have to spend long hours in the dissecting room searching fruitlessly for the otic ganglion or tracing the small arteries that form the anastomosis round the elbow joint. They now need to know only the basic essentials of anatomy with particular emphasis on their clinical relevance and this is a change that is long overdue. However, students still have examinations to pass and in this book the authors, a surgeon and an anatomist, have tried to provide a means of rapid revision without any frills. To this end, the book follows the standard format of the at a Glance series and is arranged in short, easily digested chapters, written largely in note form, with the appropriate illustrations on the facing page. Where necessary, clinical applications are included in italics and there are a number of clinical illustrations. We thus hope that this book will be helpful in revising and consolidating the knowledge that has been gained from the dissecting room and from more detailed and explanatory textbooks.

The anatomical drawings are the work of Jane Fallows, with help from Roger Hulley, who has transformed our rough sketches into the finished pages of illustrations that form such an important part of the book, and we should like to thank her for her patience and skill in carrying out this onerous task. Some of the drawings have been borrowed or adapted from Professor Harold Ellis’s superb book Clinical Anatomy (9th edition), and we are most grateful to him for his permission to do this. We should also like to thank Dr Mike Benjamin of Cardiff University for the surface anatomy photographs. Finally, it is a pleasure to thank all the staff at Blackwell Science who have had a hand in the preparation of this book, particularly Fiona Goodgame and Jonathan Rowley.

Omar Faiz

David Moffat

Preface to the second edition

The preparation of the second edition has involved a thorough review of the whole text with revision where necessary. A great deal more clinical material has been added and this has been removed from the body of the text and placed at the end of each chapter as ‘Clinical Notes’. In addition, four new chapters have been added containing some basic embryology, with particular reference to the clinical significance of errors of development. It is hoped that this short book will continue to offer a means of rapid revision of fundamental anatomy for both undergraduates and graduates working for the MRCS examination.

Once again, it is a pleasure to thank Jane Fallows, who prepared the illustrations for the new chapters, and all the staff at Blackwell Publishing, especially Fiona Pattison, Helen Harvey and Martin Sugden, for their help and cooperation in producing this second edition.

Omar Faiz

David Moffat

Preface to the third edition

For this third edition, the whole text and the illustrations have been reviewed and modified where necessary and two new chapters have been added on, respectively, anatomical terminology and the early development of the human embryo. In addition, a number of new illustrations have been added featuring modern imaging techniques. We hope that this book will continue to serve its purpose as a guide to ‘no frills’ clinical anatomy for both undergraduates and for those studying for higher degrees and diplomas.

Once again, it is a pleasure to thank the staff of Blackwell Publishing for their expert help in preparing this edition for publication, especially Martin Davies, Jennifer Seward and Cathryn Gates. Finally, we would like to thank Jane Fallows, our artist who has been responsible for all the illustrations, old and new, that form such an important part of this book.

Omar Faiz

Simon Blackburn

David Moffat

1

Anatomical terms

Some anatomical terminology

Correct use of anatomical terms is essential to accurate description. These terms are also essential in clinical practice to allow effective communication.

Anatomical position

It is important to appreciate that the surfaces of the body, and relative positions of structures, are described, assuming that the body is in the ‘anatomical position’. In this position, the subject is standing upright with the arms by the side with the palms of the hands facing forwards. In the male the tip of the penis is pointing towards the head.

Surfaces and relative positions

The ventral surface of the hand is often referred to as the palmar surface and that of the foot as the plantar surface.

Planes

Anatomical planes are used to describe sections through the body as if cut all the way through. These planes are essential to understanding cross-sectional imaging:

Movements

The following anatomical terms are used to describe movement:

In the hand, the midline is considered to be along the middle finger. Thus, abduction of the fingers refers to the motion of spreading them out. In the foot, the axis of abduction is the second toe.

The thumb is a special case. Abduction of the thumb refers to anterior movement away from the palm (see ). Adduction is the opposite of this movement.

2

Embryology

A morula, enclosed with the zona pellucida which prevents the entry of more than one spermatozoon

A blastocyst, still within the zona pellucida

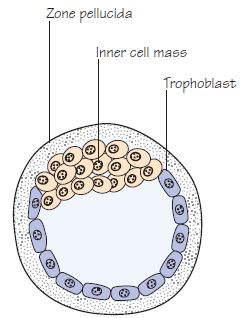

An almost completely implanted conceptus. The trophoblast has differentiated into the cytotrophoblast and the syncitiotrophoblast. The latter is invasive and breaks down the maternal tissue

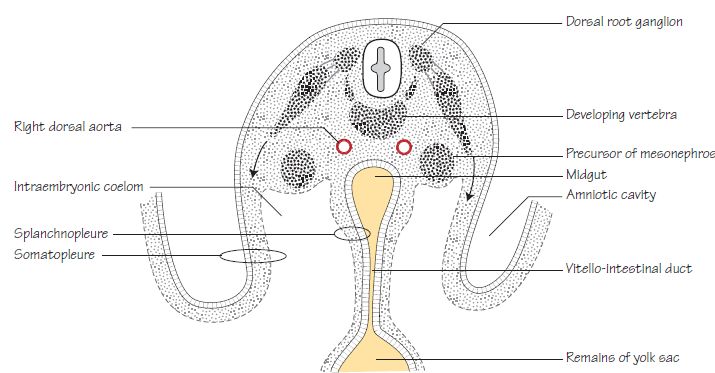

Two stages in the development of the neural tube. In (b) the lateral mesoderm is splitting into two layers. One layer, together with the ectoderm, forms the somatopleure and the other, together with the endoderm, forms the splanchnopleure

Normal pregnancy lasts 40 weeks. The first 8 weeks are termed the embryonic period, during which the body structures and organs are formed and differentiated. The fetal period runs from eight weeks to birth and involves growth and maturation of these structures.

The combination of ovum and sperm at fertilisation produces a zygote. This structure further divides to produce a ball of cells called the morula (), which develops into the blastocyst during the 4th and 5th days of pregnancy.

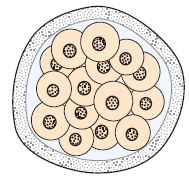

The blastocyst (): consists of an outer layer of cells called the trophoblast which encircles a fluid filled cavity. The trophoblast eventually forms the placenta. A ball of cells called the inner cell mass is attached to the inner surface of the trophoblast and will eventually form the embryo itself. At about six days of gestation, the blastocyst begins the process of implanting into the uterine wall. This process is complete by day 10.

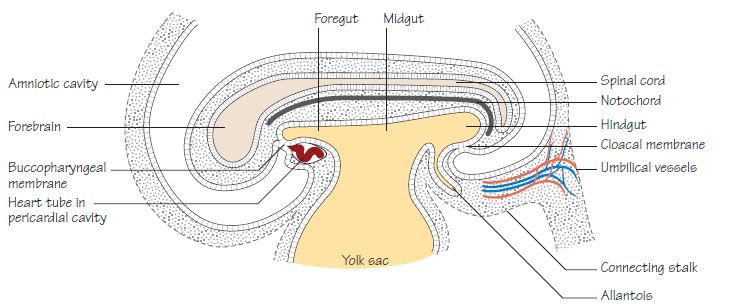

Further division of the inner cell mass during the second week of development causes a further cavity to appear, the amniotic cavity. The blastocyst now consists of two cavities, the amniotic cavity and the yolk sac (derived from the original blastocyst cavity) (). These cavities are separated by the embryonic plate. The embryonic plate consists of two layers of cells, the ectoderm lying in the floor of the amniotic cavity and the endoderm lying in the roof of the yolk sac.

Gastrulation: is the process during the third week of gestation during which the two layers of embryonic plate divide into three, giving rise to a trilaminar disc. This is achieved by the development of the primitive streak as a thickening of the ectoderm. Cells derived from the primitive streak invaginate and migrate between the ectoderm and endoderm to form the mesoderm. The embryonic plate now consists of three layers:

Ectoderm: eventually gives rise to the epidermis, nervous system, anterior pituitary gland, the inner ear and the enamel of the teeth.

Endoderm: gives rise the epithelial lining of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

Mesoderm: lies between the ectoderm and endoderm and gives rise to the smooth and striated muscle of the body, connective tissue, blood vessels, bone marrow and blood cells, the skeleton, reproductive organs and the urinary tract.

The notochord and neural plate

The notochord develops from a group of ectodermal cells in the midline and eventually forms a tubular structure within the mesodermal layer of the embryo. The notochord induces development of the neural plate in the overlying ectoderm and eventually disappears, persisting only in the intervertebral discs as the nucleus pulposus.

The neural plate invaginates centrally to form a groove and then folds to form a tube by the end of week three, a process known as neurulation (). The neural tube then becomes incorporated into the embryo, such that it comes to lie deep to the overlying ectoderm. The resultant neural tube develops into the brain and spinal cord.

Some cells from the edge of the neural plate become separated and come to lie above and lateral to the neural tube, when they become known as neural crest cells. These important cells give rise to several structures including the dorsal root ganglia of spine nerves, the ganglia of the autonomic nervous system, Schwann cells, meninges, the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, parafollicular cells of the thyroid and the bones of the skull and face.

Mesoderm

The mesodermal layer of the embryo comes to lie alongside the notochord and neural tube and is subdivided into three parts:

Paraxial mesoderm: lies nearest the midline and becomes segmented into paired clumps of cells called somites. The somites are further divided into the sclerotome, which eventually surrounds the neural tube and notochord to produce the vertebral column and ribs, and the dermatomyotome which forms the muscles of the body wall and the dermis of the skin. The segmental arrangement of the somites explains the eventual arrangement of dermatomes in the body wall and limbs ().

Intermediate mesoderm: lies lateral to the paraxial mesoderm. It eventually gives rise to the precursors of the urinary tract(see Chapter 31).

Lateral mesoderm: is involved with the formation of body cavities and the folding of the embryo ().

A separate group of cells from the primitive streak migrate around the neural plate to form the cardiogenic mesoderm, which eventually gives rise to the heart.

Folding of the embryo

The folding of the embryo commences at the beginning of the fourth week (Fig. ). The flat embryonic disc folds as a result of faster growth of the ectoderm cranio-caudally, such that it is concave towards the yolk sac and convex towards the amnion. Lateral folding occurs around the yolk sac in the same manner.

During this process, the lateral plate mesoderm splits to create the embryonic coelom or body cavity (). The inner layer is called the splanchnopleure and surrounds the yolk sac in such a way that it becomes incorporated into the embryo, forming the cells lining the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. The cranial part of the yolk sac migrates further cranially, forming the foregut, and the caudal part migrates further caudally, forming the hindgut (). As the folding of the embryo continues the yolk sac forms a small vesicle lying outside the embryo and connected to the gut by a narrow vitello-intestinal duct (see Chapter 31). The two ends of the primitive gut are separated from the amniotic cavity at the cranial end by the buccopharyngeal membrane, and the caudal end by the cloacal membrane, which are formed of ectoderm and endoderm with no intervening mesoderm. They eventually disappear to form cranial and caudal openings into the pharynx and the anal canal, respectively.

The outer layer of the lateral mesoderm is called the somatopleure. This layer is invaded by paraxial mesoderm, forming the body wall muscles. Outgrowths from the somatopleure form the limbs, which appear as buds during the 4th week of gestation.

At the end of the process of folding, the embryo contains a single internal cavity, the intra-embryonic coelom, which is eventually separated by the formation of the diaphragm into pleural and peritoneal cavities.

During this period of folding, the branchial arches develop and form a number of structures described in Chapter 76.

Between the 4th and 8th week of gestation, the limb buds, facial structures, palate, digits, gonads and genitalia, all start to differentiate, such that by the end of week eight all the external and internal structures required are present.

Lateral folding of the embryo so that it projects into the amniotic cavity. Striated muscle, from the somites, is growing down into the somatopleure (body wall) taking its nerve supply with it. Smooth muscle of the gut will develop in the mesoderm of the splanchnopleure

Lateral view to show the head and tail folds. The neck of the yolk sac will later close off, leaving the midgut intact. The allantois is functionless and will later degenerate to form the median umbilical ligament. The connecting stalk contains the umbilical vessels (intraembryonic course not shown)

Clinical notes

Sacrococcygeal teratomas: these rare tumours arise as a result of failure of the normal obliteration of the primitive streak. As the primitive streak contains cells which are capable of producing cells from all three germ cell layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm), these tumours contain elements of tissues derived from all of them.

Neural tube defects: failure of the neural plate to completely fold to form the neural tube can cause abnormalities in the formation of the central nervous system. At the most extreme, the brain fails to develop completely (anencephaly). Failure of closure of the neural tube can also cause abnormalities of the overlying structures. Spina bifida, for example, results from failure of normal fusion of the posterior part of the vertebral column (see Chapter 77).

Part 1

The thorax

3

The thoracic wall I

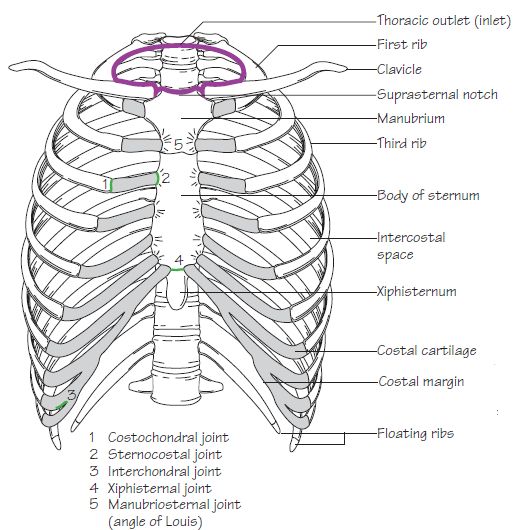

The thoracic cage. The outlet (inlet)

A typical rib

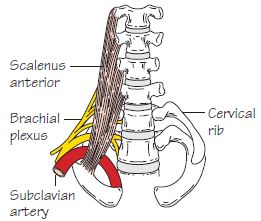

Bilateral cervical ribs. On the right side the brachial plexus is shown arching over the rib and stretching its lowest trunk

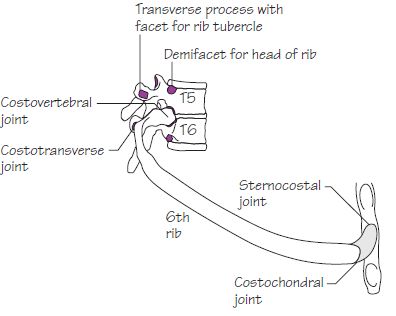

Joints of the thoracic cage

The thoracic cage

The thoracic cage is formed by the sternum and costal cartilages in front, the vertebral column behind and the ribs and intercostal spaces laterally.

It is separated from the abdominal cavity by the diaphragm and communicates superiorly with the root of the neck through the thoracic inlet ().

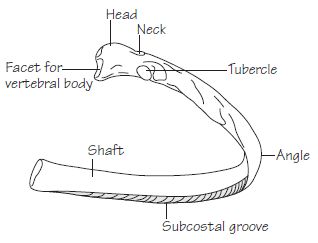

The ribs ()

Typical ribs (3rd-9th)

These comprise the following features ():

Atypical ribs (1st, 2nd, 10th, 11th, 12th)

The sternum ()

The sternum comprises a manubrium, body and xiphoid process.

Costal cartilages

These are bars of hyaline cartilage which connect the upper seven ribs directly to the sternum and the 8th, 9th and 10th ribs to the cartilage immediately above.

Joints of the thoracic cage ( and )

Clinical notes

4

The thoracic wall II

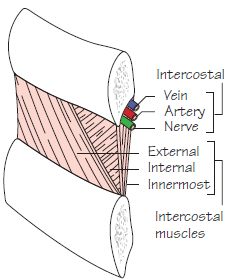

An intercostal space

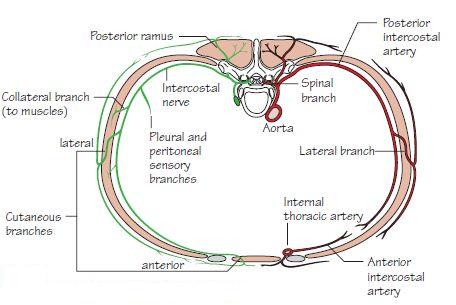

The vessels and nerves of an intercostal space

The diaphragm

The intercostal space ()

Typically, each space contains three muscles comparable to those of the abdominal wall. These include the:

The neurovascular space is the plane in which the neurovascular bundle (intercostal vein, artery and nerve) courses. It lies between the internal intercostal and innermost intercostal muscle layers.

The intercostal structures courseunder cover ofthe subcostalgroove.

Vascular supply and venous drainage of the chest wall

The intercostal spaces receive their arterial supply from the anterior and posterior intercostal arteries.

The anterior intercostal veins drain anteriorly into the internal thoracic and musculophrenic veins. The posterior intercostal veins drain into the azygos and hemiazygos systems (see ).

Lymphatic drainage of the chest wall

Lymph drainage from the:

Nerve supply of the chest wall ()

The intercostal nerves are the anterior primary rami of the thoracic segmental nerves. Only the upper six intercostal nerves reach the sternum, the remainder run initially in their intercostal spaces, then within the muscles of the abdominal wall, eventually gaining access to its anterior aspect.

Branches of the intercostal nerves include:

Exceptions include:

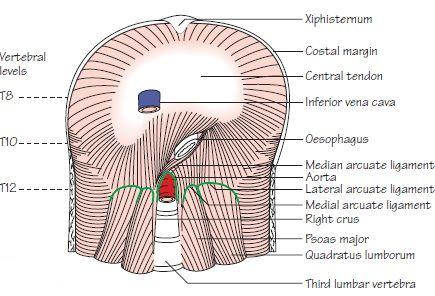

The diaphragm ()

The diaphragm separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It is composed of a peripheral muscular portion which inserts into a central aponeurosis—the central tendon.

The muscular part has three component origins:

The left crus originates from L1 and L2 only.

The medial arcuate ligament is made up of thickened fascia which overlies psoas major and is attached medially to the body of L1 and laterally to the transverse process of L1. The lateral arcuate ligament is made up of fascia which overlies quadratus lumborum from the transverse process of L1 medially to the 12th rib laterally.

The median arcuate ligament is a fibrous arch which connects left and right crura.

Openings in the diaphragm

Structures traverse the diaphragm at different levels to pass from thoracic to abdominal cavities and vice versa. These levels are as follows:

The left phrenic nerve passes into the diaphragm as a solitary structure, having passed down the left side of the pericardium ().

Nerve supply of the diaphragm

Clinical notes

5

The mediastinum I – the contents of the mediastinum

The subdivisions of the mediastinum and their principal contents

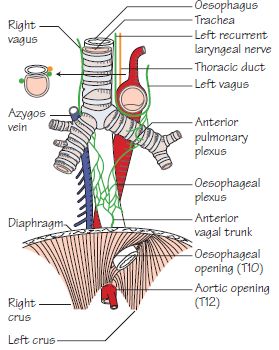

The course and principal relations of the oesophagus. Note that it passes through the right crus of the diaphragm

The thoracic duct and its areas of drainage. The right lymph duct is also shown

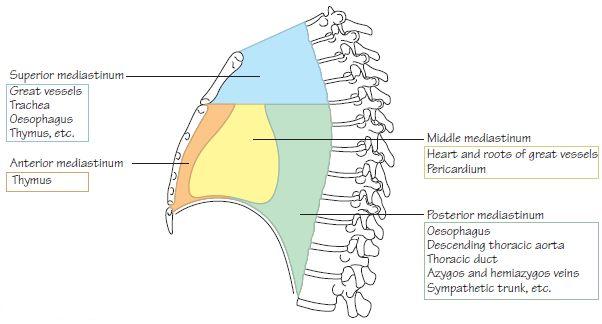

Subdivisions of the mediastinum ()

The mediastinum is the space located between the two pleural sacs. For descriptive purposes, it is divided into superior and inferior mediastinal regions by a line drawn backwards horizontally from the angle of Louis (manubriosternal joint) to the vertebral column (T4/5 intervertebral disc).

The superior mediastinum communicates with the root of the neck through the‘superior thoracic aperture’(thoracicinlet). The latter opening is bounded anteriorly by the manubrium, posteriorly by T1 vertebra and laterally by the 1st rib.

The inferior mediastinum is further subdivided into the:

The contents of the mediastinum (, , and )

The oesophagus

The venous drainage is similarly varied throughout its length:

The thoracic duct ()

The thymus gland

Clinical notes

6

The mediastinum II – the vessels of the thorax

The branches of the arch and the descending thoracic aorta

The principal veins of the thorax

The thoracic aorta ()

The ascending aorta arises from the aortic vestibule behind the infundibulum of the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk. It is continuous with the aortic arch. The arch lies posterior to the lower half of the manubrium and arches from front to back over the left main bronchus. The descending thoracic aorta is continuous with the arch and begins at the lower border of the body of T4. It initially lies slightly to the left of the midline and then passes medially to gain access to the abdomen by passing beneath the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm at the level of T12. From here, it continues as the abdominal aorta.

The branches of the ascending aorta are the right and left coronary arteries.

The subclavian arteries (see )

The subclavian arteries become the axillary arteries at the outer border of the 1st rib. Each artery is divided into three parts by scalenus anterior:

The great veins ()

The brachiocephalic veins are formed by the confluence of the subclavian and internal jugular veins behind the sternoclavicular joints. The left brachiocephalic vein traverses diagonally behind the manubrium to join the right brachiocephalic vein behind the 1st costal cartilage, thus forming the superior vena cava. The superior vena cava receives only one tributary – the azygos vein.

The azygos system of veins ()

Clinical notes