Contents

Andreas Herrmann

Hartmut K. Lichtenthaler

Patrizia Rubiolo, Barbara Sgorbini, Erica Liberto, Chiara Cordero and Carlo Bicchi

André Kessler and Kimberly Morrell

Kenji Mori

J. Richard M. Thacker and Margaret R. Train

Anthony A. Birkbeck

Meriel G. Jones

Christoph Cerny

Alan Gelperin

Christophe Laudamiel

Youngjae Byun, Young Teck Kim, Kashappa Goud H. Desai and Hyun Jin Park

Andreas Herrmann

Russell K. Monson

This edition first published 2010

© 2010 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at .

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

The publisher, the editor and the authors make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of experimental reagents, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each chemical, piece of equipment, reagent, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the authors, the editor or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. No warranty may be created or extended by any promotional statements for this work. Neither the publisher nor the editor nor the authors shall be liable for any damages arising herefrom.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The chemistry and biology of volatiles /editor, Andreas Herrmann.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-77778-7 (pbk.)

1. Volatile organic compounds.

QP550.I593 2010

612′.0157–dc22

2010013099

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9780470777787

Foreword

Volatile compounds play an important role in nature as messenger compounds to transmit selective information between species. The ubiquity of these compounds in our everyday environment has initiated a variety of research activities in the life sciences over recent decades. Both biologists and chemists became interested in exploring the role of bioactive volatile compounds in many different aspects. The evolution from molecular to supramo- lecular science has particularly influenced the research activities on the chemistry and biology of volatiles. The investigation of molecular properties beyond the single molecule required (and resulted in) numerous interdisciplinary efforts to answer important questions related to the role of these compounds in our direct environment.

Molecular recognition is one of the key aspects leading to the understanding of the biological processes involved in volatile signalling. In contrast to the investigation of host–guest interactions typically encountered in the area of pharmaceutical or biomedical research, which usually take place in aqueous solution, volatile compounds have to be diffused into the air and transported over large distances to reach their biological target. The specific feature of their volatility, as compared to other bioactive molecules, characterizes the behaviour of these molecules from their biogeneration, to their emission, analysis, release, transport, recognition and perception, up to their degradation in a specific environment.

The present book summarizes several aspects related to the chemistry and biology of volatile compounds in a structure-based approach and tries to give the reader an introduction to and general overview of the various research areas related to this particular class of molecules. It also provides perspectives along novel avenues of research and development. It should thus be of great interest to all those involved in the various facets of both basic and applied research on volatile compounds.

Jean-Marie Lehn

Strasbourg

November 2009

List of Contributors

Carlo Bicchi, Laboratory of Phytochemical Analysis, Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 9, 10125 Torino, Italy

Anthony A. Birkbeck, Firmenich SA, Division Recherche et Développement, 1 Route des Jeunes, B. P. 239, 1211 Genève 8, Switzerland

Youngjae Byun, Department of Packaging Science, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634–0320, USA

Christoph Cerny, Firmenich SA, Division Recherche et Développement, 7 Rue de la Bergère, B. P. 148, 1217 Meyrin 2, Switzerland

Chiara Cordero, Laboratory of Phytochemical Analysis, Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, Universita degli Studi di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 9, 10125 Torino, Italy

Kashappa Goud H. Desai, Department of Food Technology, 306 School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Korea University, Seoul, 136–701, Korea

Alan Gelperin, Monell Chemical Senses Center, 3500 Market St., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA, and Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA

Andreas Herrmann, Firmenich SA, Division Recherche et Développement, 1 Route des Jeunes, B. P. 239, 1211 Genève 8, Switzerland

Meriel G. Jones, The School of Biological Sciences, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, UK

André Kessler, Cornell University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, E445 Corson Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Young Teck Kim, Department of Packaging Science, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634–0320, USA

Christophe Laudamiel, DreamAir LLC, 210 Eleventh Ave, Suite 1002, New York, NY 10001, USA

Erica Liberto, Laboratory of Phytochemical Analysis, Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 9, 10125 Torino, Italy

Hartmut K. Lichtenthaler, Botanisches Institut (Molecular Biology and Biochemistry of Plants), University of Karlsruhe, Kaiserstraβe 12, 76133 Karlsruhe, Germany

Russell K. Monson, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA

Kenji Mori, The University of Tokyo, 1–20-6-1309, Mukogaoka, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113- 0023, Japan

Kimberly Morrell, Cornell University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, E445 Corson Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Hyun Jin Park, Department of Food Technology, 306 School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Korea University, Seoul, 136–701, Korea

Patrizia Rubiolo, Laboratory of Phytochemical Analysis, Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 9, 10125 Torino, Italy

Barbara Sgorbini, Laboratory of Phytochemical Analysis, Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 9, 10125 Torino, Italy

J. Richard M. Thacker, Biological Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, PA1 2BE, UK

Margaret R. Train, Biological Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, PA1 2BE, UK

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to thank Paul Deards from John Wiley & Sons, Ltd in Chichester for his invitation to edit this book; without his initiative, this project would not have been realized. Furthermore, I wish to thank Richard Davies, Gemma Valler, Rebecca Ralf and Mohan Tamilmaran, all from John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, for their continuous support during the entire publishing process.

Of course, particular thanks go to all of the authors for accepting the challenge to provide an overview of their research areas, for their enthusiasm and many stimulating discussions and exchanges during the editing process, as well as to Prof. Jean-Marie Lehn for agreeing to write a foreword to this book. As all the chapters were peer-reviewed, I would also like to thank the numerous referees for their suggestions and comments, which helped to improve the quality of the manuscripts.

Finally, I thank my superiors Dr. Daniel Benczédi, Dr. Maria-Inés Velazco and Dr. Antoine Gautier from Firmenich for supporting this project, and I thank my wife Anja for her patience. I hope this book provides an interesting and stimulating interdisciplinary approach to the chemistry and biology of volatile compounds, and that the readers forgive the errors that may have escaped the proofreading.

Andreas Herrmann

Genève

January 2010

Abbreviations

| Ac | acetyl (in structural formula) |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| ACS | American Chemical Society |

| ACSO | S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |

| AE | aroma extract |

| AEDA | aroma extract dilution analysis |

| AFNOR | Association Française de Normalisation |

| AMDIS | automatic mass spectral deconvolution |

| AMPI | acetylmethyl phosphinate |

| APC | anterior piriform cortex |

| approx. | approximatively |

| APS | adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate |

| aq. | aqueous |

| ASE | accelerated solvent extraction |

| ASES | aerosol solvent extraction system |

| ATP | adenosine-5′-triphosphate |

| BASF | Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik |

| BINAP | 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl |

| BOLD | blood oxygenation level dependent |

| BOSS | beaver dam offspring study |

| Bu | butyl (in structural formula) |

| BVOC | biogenic volatile organic compound |

| ca. | circa |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CAN-BD | carbon dioxide assisted nebulization with a bubble dryer |

| CAR | carboxen |

| cat. | catalyst/catalytic |

| CBF | cerebral blood flow |

| CD | circular dichroism (spectroscopy) |

| CDs | cyclodextrins |

| CDP | cytidine-5′-diphosphate |

| CDP-ME | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol |

| CDP-ME2P | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2-phosphate |

| CDP-MEP | diphosphocytidyl-2-methyl-D-erythritol-2-phosphate |

| C-GC | conventional gas chromatography |

| CI | Criegee intermediate |

| CI-MS | chemical ionization–mass spectrometry |

| CITAC | Cooperation on International Traceability in Analytical Chemistry |

| CITES | Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| CoA | coenzyme A |

| COBEL | children’s olfactory behaviors in everyday life |

| conc. | concentrated |

| COSY | correlation spectroscopy |

| Cp | cyclopentadienyl |

| CPCSP | continuous powder coating spraying process |

| CRC | Chemical Rubber Company |

| CS | cysteine synthase |

| CSO | alk(en)ylcysteine sulfoxide |

| CTP | cytidine-5′-triphosphate |

| 1D | one-dimensional |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| DADS | diallyl disulfide |

| DC | direct contact |

| DCMU | diuron |

| DEET | N, N-diethyl-2-toluamide |

| DELOS | depressurization of an expanded liquid organic solution |

| d.f. | film thickness |

| D-HS | dynamic headspace |

| DIBAL-H | diisobutylaluminium hydride |

| dil. | diluted |

| DMAPP | 3,3-dimethylallyl diphosphate |

| DMSO | dimethylsulfoxide |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DOX | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose |

| DOXP | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate |

| DP | dual phase |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| DTBP | di-tert-butyl peroxide |

| DVB | divinylbenzene |

| DXR | DOXP reductoisomerase |

| DXS | DOXP synthase |

| EAD | electroantennographic detection |

| EAG | electroantennogram |

| Ed. | editor/edition |

| EDGAR | emissions database for global atmospheric research |

| ee | enantiomeric excess |

| EEG | electroencephalogram |

| EHLS | epidemiology of hearing loss study |

| EO | essential oil |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency (USA) |

| er | enantiomeric ratio |

| ES-GC | enantioselective gas chromatography |

| ESP | epithiospecifier protein |

| ET | ethylene |

| Et | ethyl (in structural formula) |

| etc. | et cetera |

| EU | European Union |

| FACs | fatty acid–amino acid conjugates |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation (of the United Nations) |

| Fd | ferredoxin |

| FFNSC | flavour and fragrance natural and synthetic compounds |

| F-GC | fast gas chromatography |

| FID | flame ionization detector |

| fMRI | functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| FPP | farnesyl diphosphate |

| FQPA | Food Quality Protection Act (USA) |

| FSOT | fused silica open tubular |

| GA-3-P | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate |

| GAS | gas (or supercritical fluids) anti-solvent |

| GC | gas chromatography |

| GC-FID | gas chromatography–flame ionization detection |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| GC-qMS | gas chromatography–quadrupole mass spectrometry |

| GC-O | gas chromatography–olfactometry |

| GGPP | geranylgeranyl diphosphate |

| γGP | γ-glutamyl sulfoxide peptide derivative |

| GPP | geranyl diphosphate |

| GS | glucosinolate |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | oxidised glutathione disulfide |

| HCC-HS | high concentration capacity headspace technique |

| HIPVs | herbivore-induced plant volatiles |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| HMBC | heteronuclear multiple bond coherence |

| HMBPP | 4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl diphosphate |

| HMG | hydroxyl-methylglutaryl |

| HMPA | hexamethylphosphoramide |

| HMQC | heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence |

| HPC | hydroxypropyl cellulose |

| HPLC | high performance liquid chromatography |

| HPOD | hydroperoxyoctadienoate |

| HR | heart rate |

| HS | headspace |

| HS-LPME | headspace–liquid phase microextraction |

| HS-MS | headspace–mass spectrometry |

| HSQC | heteronuclear single quantum coherence |

| HSSE | headspace sorptive extraction |

| HS-SPDE | headspace–solid phase dynamic extraction |

| HS-SPME | headspace–solid phase microextarction |

| HS-SMSE | headspace–silicon membrane sorptive extraction |

| HS-STE | headspace–sorptive tape extraction |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid |

| IATA | International Air Transport Association |

| i.d. | inner diameter |

| IFF | International Flavors and Fragrances Inc. |

| IFRA | International Fragrance Association |

| INCAT | inside needle capillary adsorption trap |

| IOFI | International Organization of the Flavour Industry |

| IPP | isopentenyl diphosphate |

| IRMS | isotope ratio mass spectrometry |

| IspD | CDP-ME synthase |

| IspE | CDP-ME kinase |

| IspF | MEcPP synthase |

| IspG | HMBPP synthase |

| IspH | HMBPP reductase |

| ISTD | internal standard |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| LC | liquid chromatography |

| LDA | lithium diisopropylamine |

| LF | lachrymatory factor |

| LFS | lachrymatory factor synthase |

| LMCS | longitudinally modulated cryogenic system |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LOQ | limit of quantification |

| LOX3 | lipoxygenase 3 (gene) |

| MACR | methacrolein |

| MAE | microwave-assisted extraction |

| MA-HD | microwave-assisted hydrodistillation |

| MAM | methylthioalkylmalate |

| MBO | 2-methylen-3-buten-2-ol |

| MCSO | S-methyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |

| MD | multidimensional |

| ME | male equivalents |

| Me | methyl (in structural formula) |

| MEcPP | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate |

| MeJA | methyl jasmonate |

| MeSA | methyl salicylate |

| MEP | 2-C-methylerythritol-4-phosphate |

| MESI | membrane extraction sorbent interface |

| MGL | methionine-γ-lyase |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| MHE | multiple headspace extraction |

| ML | maple lactone |

| MME | membrane microextraction |

| MS | mass spectrometry, mass spectrometer |

| Ms | mesyl (SO2CH3; in structural formula) |

| MVA | mevalonic acid/mevalonate |

| MVL | mevalonolactone |

| MVK | methyl vinyl ketone |

| MW | molecular weight |

| MYB | myeloblast |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NB | narrow bore (column) |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NMO | N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NOESY | nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy |

| NPQ | nonphotochemical quenching |

| NS | nosespace |

| Nu | nucleophile (in structural formula) |

| OAV | odour activity values |

| OB | olfactory bulb |

| OCO | oral cavity only (exposure) |

| OFC | orbitofrontal cortex |

| OP | other phytohormones |

| OPE | ozone production efficiency |

| OR | olfactive receptor |

| ORNs | olfactive receptor neurons |

| OV | Ohio Valley Speciality Chemical (brand of stationary phases) |

| OXP-01 | 2-decyl-1-oxaspiro[2.2]pentane |

| OXP-04 | 2-(4-hydroxybutyl)-1-oxaspiro[2.2]pentane |

| PAN | peroxyacetyl nitrate |

| PAPS | adenosine-3′-phosphate-5′-phosphosulfate |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PCSO | S-propyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |

| portable document format | |

| PeCSO | trans-S-1-propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |

| PEG | poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PBP1 | pheromone binding protein 1 |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PDMS | poly(dimethylsiloxane) |

| PEP | phosphoenol pyruvate |

| PG | protecting group |

| PGA | phosphoglyceric acid |

| PGSS | particles from gas-saturated solutions |

| Ph | phenyl (in structural formula) |

| PLP | pyridoxal-5′-phosphate |

| PMHS | poly(methylhydrosiloxane) |

| pp. | pages |

| PPC | posterior piriform cortex |

| PTR-MS | proton transfer reaction–mass spectrometer |

| qMS | quadrupole mass spectrometry (detector) |

| quant. | quantitative |

| RA | retinoic acid |

| ref. | reference |

| RESS | rapid expansion of supercritical fluids |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| RSD | relative standard deviation |

| r.t. | room temperature |

| RTL | retention time locking |

| RubisCO | ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| SAA | supercritical assisted atomization |

| SAS | supercritical fluids (or gas) anti-solvent |

| SAT | serine acetyltransferase |

| SBSE | stir bar sorptive extraction |

| SC | skin conductance |

| SCC-GC | short capillary column gas chromatography |

| sc-CO2 | supercritical CO2 |

| SDE | simultaneous distillation–extraction |

| SDOIT | San Diego odor identification test |

| SEDS | solution enhanced dispersion by supercritical fluids |

| SFE | supercritical fluid extraction |

| SFEE | supercritical fluid extraction of emulsions |

| S-HS | static headspace |

| SIM | single ion monitoring |

| SIM-MS | single ion monitoring–mass spectrometry |

| SIM-qMS | single ion monitoring–quadrupole mass spectrometry |

| SiSTEx | solvent in silicone tube extraction |

| SMP | skimmed milk powder |

| SMSE | silicon membrane sorptive extraction |

| SOA | secondary organic aerosol |

| SPACE | solid phase aroma concentrate extraction |

| SPME | solid phase microextraction |

| SROs | stress-related odours |

| SSI | supercritical solvent impregnation |

| S&T-HS | static and trapped headspace |

| TAS | total analysis systems |

| TCD | thermal conductivity detector |

| TDS | thermodesorption system |

| tert | tertiary |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TIC | total ion current |

| TIC-MS | total ion current–mass spectrometry |

| TLC | thin-layer chromatography |

| TMS | trimethylsilyl (protecting group) |

| TMT | thiol methyltransferases |

| TOF | time of flight |

| TPLSM | two-photon laser scanning microscopy |

| TRGs | temperature-responsive gels |

| Ts | tosyl (SO2C6H4CH3; in structural formula) |

| p-TSA | para-toluenesulfonic acid |

| UFM-GC | ultra-fast module gas chromatography |

| UK | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| USA | United States of America |

| UV | ultraviolet (spectroscopy) |

| UV/Vis | ultraviolet/visible (spectoscopy) |

| VOC | volatile organic compound |

| Vol. | volume |

| WOF | warmed-over flavour |

| WPC | whey protein (isolate) concentrate |

Names of scientific journals are abbreviated according to the Chemical Abstracts Service Source Index

1

Volatiles – An Interdisciplinary Approach

1.1 Introduction

Volatiles, and in particular biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs), are everywhere. They directly and indirectly influence the lives of many plant and insect species, and even human beings in many ways. Transported by diffusion through the air, they perform numerous functions, for example as so-called ‘semiochemicals’, ‘infochemicals’ or ‘pheromones’ for the communication between insects and/or plants,1,2 for (insect) mating2–4 or even, as a consequence of their pleasant taste or smell to humans, as flavours and fragrances.4,5 Without volatile compounds, life on earth as we know it would be impossible. The structural variety in these compounds, which are generally based on a hydrocarbon skeleton with oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur as the most common heteroatoms, is almost infinite and always perfectly adapted to the specific role these molecules play in nature.

Biogenic VOCs are usually highly selective for a given target. This selectivity is presumably the most important property of these different compounds which, of course, is defined by their molecular structure (and the spatial arrangement of the different functional groups from which they are composed) and usually results in a very low ‘detection threshold’ of a given compound to its target species.6 This means that the receptor of the receiving species can selectively detect specific molecules at very low concentrations in the air (typically expressed in ng 1−1 of air) which, in some cases, can be a few molecules.

In contrast to many other target-specific compounds found in nature, volatiles are characterized by (relatively) high vapour pressures, allowing their efficient evaporation from various surfaces. This enables their transport through the air and thus to reach their biological target. Nevertheless, the term ‘volatile’ is usually not well defined, and the vapour pressures of compounds considered to be volatile can vary over several orders of magnitude.7 Some representative volatile compounds such as 1–18 are listed in . Their vapour pressures span nine orders of magnitude, ranging from the highly volatile methane thiol (1) to the relatively nonvolatile insect pheromone bombykol (18) from the silkworm moth Bombyx mori.

Furthermore, biogenic VOCs are generally characterized as being rather ‘hydrophobic’ which facilitates, among others, their efficient evaporation from water-based media into the air. The polarity of different compounds is usually expressed as the logarithm of their octanol/water partition coefficients (log Po/w);7,8 the corresponding values for compounds 1–18 are indicated in . Once again, one can see that these data vary considerably, ranging from values below 1 for relatively polar compounds 1 and 3 to highly apolar molecules such as 13 with a log Po/w above 9.

The numerous areas of research dealing with the investigation of volatile compounds are as varied as their structures and their physicochemical properties. Biologists and chemists have become interested in these compounds for various reasons. Because the same volatile compounds can have different functions, volatiles have been discussed separately by the specialists in different areas. Nevertheless, the same molecular structure is often of interest to a wide variety of quite different research topics such as the biosynthesis of the given volatile in plants, its analysis in compound mixtures by different techniques, its particular biological role as a signalling compound or pheromone, its use in pest control and, if associated with a pleasant taste or smell, as a flavour or fragrance, its chemical synthesis, the mechanism of its perception, its behaviour through encapsulation and processing, its controlled release, right up to its degradation in the environment (). In the following section the different interdisciplinary research aspects associated with a given compound are illustrated with the example of (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-ol (geraniol, 11) as a typical volatile molecule with an average vapour pressure and log Po/w. At the same time, these aspects will allow the introduction of the various topics presented in the different chapters of this book and thus illustrate a typical lifecycle of volatile compounds from their biogeneration, via their release into the air, their role as semiochemicals, their specific recognition, through to their degradation in the atmosphere.

1.2 Geraniol – A Typical Example

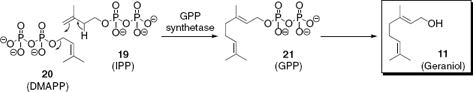

Biogenic, bioactive volatiles, such as geraniol (11), are generated in plants from small precursor molecules in multistep enzymatic processes. As one of the main constituents of the essential oils of various rose species, monoterpene alcohol 11 is biosynthesized by condensation of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP, 19) and 3,3-dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP, 20) with the help of geranyl diphosphate (GPP) synthetase, followed by dephosphorylation of GPP (21),9 as depicted in . GPP is of particular importance because it is the precursor of geraniol and of many different monoterpenes. The following chapter (Chapter 2) gives a general introduction to the various mechanisms involved in the biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids and illustrate the structural variety of terpenes generated by plants.

Vapour pressures and (logarithmic) octanol/water partition coefficients (log Po/w) of a series of representative volatile compounds

aNote: Values calculated according to ref. 7.

Aspects of interdisciplinary research, using the example of geraniol

The identification and quantification of the individual constituents isolated from plants is an important aspect in the understanding of the biochemical processes involved in their generation. Volatiles are analysed mainly by gas chromatography (GC), usually coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and some other more specific techniques. The volatility of such compounds allows specific sample preparation methods such as static and dynamic headspace analysis to be employed.10 Chapter 3 gives an account of the numerous methods used for the analysis of volatile compounds emitted from plants by discussing the scopes and limitations of the different techniques.

Biosynthesis of geraniol

Plants, insects and other animals use volatile compounds for their communication with the environment.1 Besides its emission from flowers to attract pollinators, geraniol (11) is also a member of a class of so-called ‘herbivore-induced plant volatiles’ (HIPVs). Plants emit these compounds to defend themselves against herbivore attack by attracting natural enemies of the herbivores responsible for the plant damage. As an example, geraniol was found to attract wasps and flesh flies of the Braconidae and Sarcophagidae families, respectively.11 The specific aspects and implications of volatile signalling for plants and insects are discussed in Chapter 4.

Geraniol (11) has also been identified in the secretions of the Nasonov gland of honeybees, where the compound, together with a series of other volatiles, serves as a pheromone to mark the entrance of the hive, for mating and orientation, as for example for swarm clustering or guidance to flowers.12 Using insects and mammals as examples, Chapter 5 presents the classification, structural particularities and roles of pheromones in chemical communication.

Apart from acting as an attractant, geraniol was also found to repel certain insects, such as the malaria-transmitting mosquito Anopheles gambiae.13 Essential oils (EOs) containing geraniol (and other insect-repellent compounds) have thus been used for protection against blood-feeding insects, whilst other volatiles have been identified as being useful for the protection of agricultural crops. The potential to selectively repel or kill certain insects is an important aspect of volatiles in the area of pest control, as documented in more detail in Chapter 6.

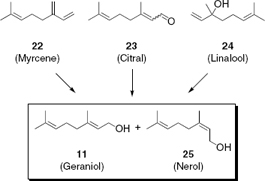

Although geraniol (11) is readily available from natural sources, several methods for its synthesis have been proposed, some of which are illustrated in . Typically the compound is prepared from other monoterpenes14 such as myrcene (22), citral (23) or linalool (24) to usually afford mixtures of geraniol (11) and nerol (25). The selective preparation of specific isomers in high purities is therefore one of the major achievements of organic synthesis. Chapter 7 summarizes some of the challenges encountered in the synthesis of natural and non-natural fragrances. Besides allowing the preparation of natural compounds which are difficult to be accessed in large quantities, organic chemistry has delivered a multitude of new and entirely synthetic compounds, in particular for use in perfumery.

Chemical synthesis of geraniol

Certain volatile molecules are also part of our everyday life as flavours present in our daily nutrition. Monoterpenes, such as geraniol, contribute to the floral aroma of a series of grape varieties used in wine-making.15 Many flavour volatiles, so-called ‘secondary metabolites’ in fruits or vegetables, are generated from fats or amino acid precursors during ripening. The mechanisms involved in the biogeneration and metabolism of these compounds are important for food preparation as well as in aspects of nutrition and health. Besides the terpenoid structures, sulfur- and nitrogen-containing compounds are particularly important flavour constituents. Whereas Chapter 8 discusses the biogeneration and the role of a variety of sulfur compounds encountered in onion and garlic, Chapter 9 focuses on the generation of flavours during food processing, as for example in the so-called ‘Maillard reaction’,16 with particular focus on the thermal effects detected during cooking. Because not all volatiles have a pleasant taste or smell, the understanding of these processes is also important in allowing the efficient minimisation of undesired malodour formation under various conditions.

Once the volatiles have reached their target, they are recognized by specific receptors, which trigger an electric signal perceived by the brain. The mechanisms of olfactive perception are quite complicated in both insects and humans. The general importance of understanding the mechanisms of olfaction was underlined by the granting of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Axel and Buck in 2004 for their discoveries of odorant receptors and the organisation of the olfactory system,17 which stimulated a general interest in exploring the chemistry and biology of volatile compounds in the life sciences.18 Chapter 10 gives a general overview of the basic principles and mechanisms involved in (human) perception.

To humans geraniol (11) has a pleasant, sweet, floral smell and is therefore among the most frequently used perfumery compounds.14,19 Perfumes are usually mixtures of many different volatile compounds created at the interface between art and science. In the general public, perfumery is most commonly associated with ‘fine fragrances’, but perfumes are also an important ingredient in body care and household products, such as shampoos, soaps, creams, deodorants, shower gels, surface cleaners, detergents, softeners and many others. Chapter 11 illustrates the particular artistic aspects of perfumery creation. For their creations, perfumers require a multitude of different molecules at their disposal. These compounds can be natural compounds extracted from natural raw materials, prepared selectively by biotechnical processes or by organic synthesis.

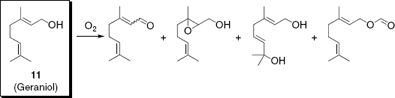

Many terpenes are sensitive to oxidation, either by oxygen in the air20 or by a variety of bio-oxidation processes initiated by bacteria and fungi21 (). To efficiently use susceptible terpenes such as geraniol (11) in commercial product formulations they have to be protected against (oxidative) degradation by using various encapsulation techniques.22 Chapter 12 examines a series of flavour encapsulation processes which are most commonly used to increase the stability of food ingredients and to control their release in applications.

Compounds formed by air oxidation of geraniol

Release of geraniol by enzymatic cleavage of its glycoside conjugate

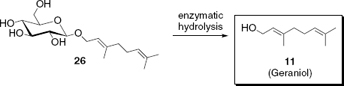

Besides the physical capturing of volatiles within capsules and other matrices, ‘chemical’ delivery systems have been developed to slowly release small quantities of volatiles to allow the duration of their perception to be increased. Nature stores and transports terpenes, such as geraniol (11) as hydrosoluble glycoside conjugates (e.g. 26) before releasing them by enzymes into the environment,23 which served as an inspiration to use fragrance conjugates as controlled release systems in practical applications (). Chapter 13 gives an account of the various techniques which have been developed for the release of fragrance molecules via covalent bond cleavage of different natural and non-natural fragrance precursors, so-called ‘profragrances’ or ‘properfumes’. Of course, this concept can be generally applied to the controlled release of volatiles in other areas, as for example to attract or repel insects in pest control.

Another important area of interest concerns the (natural) biodegradation of volatiles in water or soil by the activity of various microorganisms. Nevertheless, as a consequence of their volatility, biogenic VOCs can also reach the atmosphere, where they are exposed to particular reaction conditions leading to their rapid degradation ().24 The investigation of these processes becomes more and more important to understand the lifecycle of natural compounds and to estimate the impact of biogenic volatiles on our planet’s climate. This book therefore concludes with a discussion of this important aspect with a summary of the gas phase chemistry of biogenic VOCs in the atmosphere (Chapter 14) as one aspect of their natural biodegradation.

Degradation of geraniol in the atmosphere

1.3 Conclusion

The different topics of research mentioned above for one representative molecule such as geraniol (11) indicate the broad variety of interest in volatile compounds. With the structures of the volatiles being the common link to all the different research areas presented in the following chapters, it is on purpose that the reader will find many common molecular structures illustrating the different chapters and thus referring to the different domains of research grouped together in this book. To date, these aspects have mainly been discussed separately by specialists from different areas, and several textbooks and reviews on the individual topics are available. However, the goal of this book is to provide an interdisciplinary approach on the various aspects of the chemistry and biology of volatile compounds to a reader generally interested in this area. The chapters constituting this book are not intended to give an extensive or comprehensive review of each of the specific topics, but rather represent a conceptual and quite general overview of a series of different research areas. They should give the reader the opportunity to discover the basic aspects of the different disciplines, to illustrate parallels between the different domains and, with the numerous references given in the different chapters, to invite further reading.

As depicted in , there is a certain overlap between the different research areas, which of course results from the discussion of similar aspects from different viewpoints in several of the chapters. At the same time, other important aspects of research on volatile compounds might only be briefly mentioned or even entirely omitted. However, to keep this book within a reasonable length, this seemed to be unavoidable.

The respective interest in volatile compounds from so many different angles is an excellent occasion for the exchange and common learning in chemistry and biology, and I hope that the present book will stimulate discussions and collaborations within a highly interdisciplinary research field.

References

1. For a selection of recent reviews, see for example: (a) N. Dudareva, E. Pichersky, J. Gershenzon, Biochemistry of plant volatiles, Plant Physiol., 135, 1893–1902 (2004); (b) J. K. Holopainen, Multiple functions of inducible plant volatiles, Trends Plant Sci., 9, 529–533 (2004); (c) N. Bakthavatsalam, P. L. Tandon, Interactions between plant chemicals and the entomophages, Pestology, 29, 17–31 (2005); (d) Special section on plant volatiles, Science, 311, 803–819 (2006); (e) M. D’Alessandro, T. C. J. Turlings, Advances and challenges in the identification of volatiles that mediate interactions among plants and arthropods, Analyst, 131, 24–32 (2006); (f) L. G. W. Bergström, Chemical communication by behaviour-guiding olfactory signals, Chem. Commun., 3959–3979 (2008); (g) S. B. Unsicker, G. Kunert, J. Gershenzon, Protective perfumes: the role of vegetative volatiles in plant defense against herbivores, Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 12, 479–485 (2009).

2. For reviews, see for example: The Chemistry of Pheromones and Other Semiochemicals, S. Schulz (Ed.), Topics in Current Chemistry, Vols 239 and 240, Springer, Berlin, 2004 and 2005, and references cited therein.

3. For a selection of some recent reviews, see for example: (a) T. C. Baker, J. J. Heath, Pheromones: function and use in insect control, Compr. Mol. Insect Sci., 6, 407–459 (2005); (b) L. Stowers, T. F. Marton, What is a pheromone? Mammalian pheromones reconsidered, Neuron, 46, 699–702 (2005); (c) A. Bigiani, C. Mucignat-Caretta, G. Montani, R. Tirindelli, Pheromone reception in mammals, Rev. Physiol., Biochem., Pharmacol., 154, 1–35 (2005); (d) P. A. Brennan, F. Zufall, Pheromonal communication in vertebrates, Nature, 444, 308–315 (2006); (e) K. D. Broad, E. B. Keverne, More to pheromones than meets the nose, Nat. Neurosci., 11, 128–129 (2008).

4. E. Breitmaier, Terpenes – Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheromones, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006.

5. See for example: (a) Flavours and Fragrances – Chemistry, Bioprocessing and Sustainability, R. G. Berger (Ed.), Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2007; (b) Chemistry and Technology of Flavors and Fragrances, D. J. Rowe (Ed.), Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2005.

6. Standardized Human Olfactory Thresholds, M. Devos, F. Patte, J. Rouault, P. Laffort, L. J. Van Gemert (Eds), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990.

7. Vapour pressures and log Po/w were calculated with the EPI suite PBT calculator 1.0.0 based on the EPIwin program, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington D. C., 2000.

8. (a) A. Leo, C. Hansch, D. Elkins, Partition coefficients and their use, Chem. Rev., 71, 525–616 (1971); (b) A. J. Leo, Calculating log Poctfrom structures, Chem. Rev., 93, 1281–1306 (1993).

9. See for example: (a) T. Suga, T. Shishibori, The biosynthesis of geraniol and citronellol in Pelargonium roseum Bourbon, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 46, 3545–3548 (1973); (b) D. V. Banthorpe, D. R. S. Long, C. R. Pink, Biosynthesis of geraniol and related monoterpenes in Pelargonium graveolens, Phytochemistry, 22, 2459–2463 (1983); (c) V. S. Dubey, An overview of geraniol biosynthesis in Palmarosa (Cymbopogon martinii Roxb. var. motia) and its biological and pharmacological properties, Recent Progr. Med. Plants, 11, 75–97 (2006).

10. See for example: (a) K. Demeestere, J. Dewulf, B. De Witte, H. Van Langenhove, Sample preparation for the analysis of volatile organic compounds in air and water matrices, J. Chromatogr. A, 1153, 130–144 (2007); (b) P. López, M. A. Huerga, R. Batlle, C. Nerin, Use of solid phase microextraction in diffusive sampling of the atmosphere generated by different essential oils, Anal. Chim. Acta, 559, 97–104 (2006).

11. See for example: D. G. James, Further field evaluation of synthetic herbivore-induced plant volatiles as attractants for beneficial insects, J. Chem. Ecol., 31, 481–495 (2005).

12. See for example: (a) T. Schmitt, G. Herzner, B. Weckerle, P. Schreier, E. Strohm, Volatiles of foraging honeybees Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and their potential role as semio-chemicals, Apidologie, 38, 164–170 (2007); (b) I. Lamprecht, E. Schmolz, B. Schricker, Pheromones in the life of insects, Eur. Biophys. J., 37, 1253–1260 (2008).

13. M. O. Omolo, D. Okinyo, I. O. Ndiege, W. Lwande, A. Hassanali, Repellency of essential oils of some Kenyan plants against Anopheles gambiae, Phytochemistry, 65, 2797–2802 (2004).

14. H. Surburg, J. Panten, Common Fragrance and Flavor Materials, 5th edn, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006.

15. See for example: F. Luan, A. Mosandl, A. Münch, M. Wüst, Metabolism of geraniol in grape berry mesocarp of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Scheurebe: demonstration of stereoselective reduction, E/Zisomerization, oxidation and glycosylation, Phytochemistry, 66, 295–303 (2005).

16. See for example: (a) H. Nursten, The Maillard Reaction: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Implications, The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2005; (b) The Maillard Reaction: Chemistry at the Interface of Nutrition, Aging, and Disease, J. W. Baynes, V. M. Monnier, J. M. Ames, S. R. Thorpe (Eds), New York Academy of Sciences, New York, 2005; (c) Process and Reaction Flavors: Recent Developments, ACS Symp. Ser., Vol. 905, D. K. Weerasinghe, M. K. Sucan (Eds), American Chemical Society, Washington D. C., 2005.

17. (a) R. Axel, Scents and sensibility: a molecular logic of olfactory perception (Nobel lecture) Angew. Chem., 117, 6264–6282 (2005); Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 44, 6110–6127 (2005); (b) L. B. Buck, Unraveling the sense of smell (Nobel lecture) Angew. Chem., 117, 6283–6296 (2005); Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 44, 6128–6140 (2005).

18. Special section on chemical sensing, Nature, 444, 287–321 (2006).

19. S. Arctander, Perfume and Flavor Chemicals, published by the author, Montclair, 1969.

20. C. Bäcktorp, L. Hagvall, A. Börje, A.-T. Karlberg, P.-O. Norrby, G. Nyman, Mechanism of air oxidation of the fragrance terpene geraniol, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 4, 101–106 (2008).

21. J. L. Bicas, A. P. Dionísio, G. M. Pastore, Bio-oxidation of terpenes: an approach for the flavor industry, Chem. Rev., 109, 4518–4531 (2009).

22. (a) A. Madene, M. Jacquot, J. Scher, S. Desorby, Flavour encapsulation and controlled release – a review, Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., 41, 1–21 (2006); (b) M. A. Augustin, Y. Hemar, Nano- and micro-structured assemblies for encapsulation of food ingredients, Chem. Soc. Rev., 38, 902–912 (2009).

23. See for example: J.-E. Sarry, Z. Günata, Plant and microbial glycoside hydrolases: volatile release from glycosidic aroma precursors, Food Chem., 87, 509–521 (2004).

24. (a) F. M. N. Nunes, M. C. C. Veloso, P. A. de P. Pereira, J. B. de Andrade, Gas-phase ozonolysis of the monoterpenoids (S)-(+)-carvone, (R)-(−)-carvone, (−)-carveol, geraniol and citral, Atmos. Environ., 39, 7715–7730 (2005); (b) C. D. Forester, J. E. Ham, J. R. Wells, Geraniol (2,6-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-8-ol) reactions with ozone, and OH radical: rate constants and gas-phase products, Atmos. Environ., 41, 1188–1199 (2007).