Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Related Titles

Cordova, A. (ed.)

Catalytic Asymmetric Conjugate Reactions

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32411-8

Cossy, J., Arseniyadis, S., Meyer, C. (eds.)

Metathesis in Natural Product Synthesis

Strategies, Substrates and Catalysts

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32440-8

Blaser, H.-U., Federsel, H.-J. (eds.)

Asymmetric Catalysis on Industrial Scale

Challenges, Approaches and Solutions

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32489-7

Quin, L. D., Tyrell, J.

Fundamentals of Heterocyclic Chemistry

Importance in Nature and in the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals

2010

E-Book

ISBN: 978-0-470-62653-5

The Editor

Prof. Dr. Valentine G. Nenajdenko

Moscow State University

Leninskie Gory

119992 Moscow

Russia

All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and publisher do not warrant the information contained in these books, including this book, to be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in mind that statements, data, illustrations, procedural details or other items may inadvertently be inaccurate.

Library of Congress Card No.: applied for

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <>.

© 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany

All rights reserved (including those of translation into other languages). No part of this book may be reproduced in any form – by photoprinting, microfilm, or any other means – nor transmitted or translated into a machine language without written permission from the publishers. Registered names, trademarks, etc. used in this book, even when not specifically marked as such, are not to be considered unprotected by law.

Composition Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong

Cover Design Schulz Grafik-Design, Fußgönheim

Print ISBN: 978-3-527-33043-0

ePDF ISBN: 978-3-527-65256-3

ePub ISBN: 978-3-527-65255-6

mobi ISBN: 978-3-527-65254-9

oBook ISBN: 978-3-527-65253-2

Preface

Isocyanide (isonitrile) chemistry began in 1859 when Lieke obtained the first compound of this type. In 1958, isocyanides became generally available by dehydration of formamides prepared from primary amines. This discovery and many other important inventions in the chemistry of isocyanides have been attributed to Ivar Ugi. He was probably the first person to understand the exceptional nature of isocyano functionality and its rich synthetic possibilities. Being stable carbenes, isonitriles are highly reactive compounds that can react with almost any type of reagents (electrophiles, nucleophiles and even radicals). Today isocyanide chemistry is a broad and important part of organic chemistry; however inorganic, coordination, polymeric, combinatorial and medicinal chemistry explore the rich reactivity of isonitriles as well. Multicomponent reactions with isocyanides are used for synthesis of broad varieties of peptides and peptide mimetics. The renaissance of isocyanide chemistry was at the end of the 20th century when thousands of new compounds libraries became highly desirable for diversity-oriented synthesis, high-throughput screening and drug discovery. Isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions are out of competition in terms of effectiveness and economy to synthesize drugs like compounds or natural compounds only in a single synthetic step.

In this book, an effort has been made to provide a comprehensive modern view of all the most significant branches of isocyanide chemistry, demonstrating how important are these compounds to date and how significant is their impact on chemistry. It should be pointed out that the book Isonitrile Chemistry was published by Ivar Ugi in 1971. Since then a number of excellent reviews and monograph chapters regarding isocyanides, in particular their multicomponent reactions, have been published. However, a book devoted to the chemistry of isocyanides has not been published for more than 40 years.

It is a great honor and pleasure for me to be the editor of this book. I would like to thank all the authors of the individual chapters for their excellent contributions. These outstanding scientists are known experts in the field of isocyanide chemistry. This book is a result of worldwide cooperation of contributors from many countries. I would like also to thank all my collaborators at Wiley-VCH for help to realize this project.

I also wish to use this opportunity to mention my personal love for isocyanide chemistry. Almost 25 years ago as a student, I read Isonitrile Chemistry by Ivar Ugi. Such a beautiful and rich chemistry made me dream to do something important and interesting in this field. However, it was impossible at that time because I was still a student. Nevertheless, I synthesized my first isocyanide and had experience with specific odors of isonitriles. My next step to isocyanides was the conference in Yaroslavl, Russia, in 2001, where I met Ivar Ugi. We had a long and fruitful discussion, and this talk supported me significantly. Since then my laboratory has been involved in isocyanide chemistry. I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of an outstanding chemist and major pioneer of isocyanide chemistry, Ivar Ugi.

Valentine G. Nenajdenko

Moscow, 2012

List of Contributors

Niels Akeroyd

Radboud University Nijmegen

Institute for Molecules and Materials

Heyendaalseweg 135

6525 AJ Nijmegen

The Netherlands

Irini Akritopoulou-Zanze

Abbott Laboratories

Scaffold-Oriented Synthesis

Abbott Park, IL 60064

USA

Muhammad Ayaz

The University of Arizona

College of Pharmacy

BIO5 Oro Valley

Tucson, AZ 85737

USA

Luca Banfi

Università a degli Studi di Genova

Dipartimento di Chimica e Chimica Industriale

Via Dodecaneso 31

16146 Genova

Italy

Mikhail V. Barybin

The University of Kansas

Department of Chemistry

1251 Wescoe Hall Drive

Lawrence, KS 66045

USA

Andrea Basso

Università a degli Studi di Genova

Dipartimento di Chimica e Chimica Industriale

Via Dodecaneso 31

16146 Genova

Italy

Fabio De Molinerv

The University of Arizona

College of Pharmacy

BIO5 Oro Valley

Tucson, AZ 85737

USA

Justin Dietrichv

The University of Arizona

College of Pharmacy

BIO5 Oro Valley

Tucson, AZ 85737

USA

Alexander Dömling

University of Pittsburgh

School of Pharmacy

Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Pittsburgh, PA 15261

USA

Laurent El Kaïm

Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Techniques Avancées

Unité Chimie et Procédés

UMR 7652

CNRS-ENSTA-Polytechnique

32 Bd Victor

75012 Paris

France

Niels Elders

VU University Amsterdam

Department of Chemistry & Pharmaceutical Sciences

De Boelelaan 1083

1081 HV Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Laurence Grimaud

Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Techniques Avancées

Unité Chimie et Procédés

UMR 7652

CNRS-ENSTA-Polytechnique

32 Bd Victor

75012 Paris

France

Anton V. Gulevich

Moscow State University

Department of Chemistry

Leninskie Gory

Moscow 119991

Russia

Yijun Huang

University of Pittsburgh

School of Pharmacy

Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Pittsburgh, PA 15261

USA

Christopher Hulme

The University of Arizona

College of Pharmacy

BIO5 Oro Valley

Tucson, AZ 85737

USA

Nicola Kielland

Barcelona Science Park

University of Barcelona

Baldiri Reixac 10-12

08028 Barcelona

Spain

Mikhail Krasavin

Griffith University

Eskitis Institute

Brisbane, QLD 4111

Australia

Rodolfo Lavilla

Barcelona Science Park

University of Barcelona

Baldiri Reixac 10-12

08028 Barcelona

Spain

Konstantin V. Luzyanin

Technical University of Lisbon

Centro de Química Estrutural

Instituto Superior Técnico

1049-001 Lisbon

Portugal

Ali Maleki

Iran University of Science and Technology

Department of Chemistry

Narmak

Tehran 16846-13114

Iran

John J. Meyers, Jr

The University of Kansas

Department of Chemistry

1251 Wescoe Hall Drive

Lawrence, KS 66045

USA

Maxim A. Mironovv

Ural Federal University

Department of Technology for Organic Synthesis

str. Mira, 19

620002 Ekaterinburg

Russia

Brad M. Neal

The University of Kansas

Department of Chemistry

1251 Wescoe Hall Drive

Lawrence, KS 66045

USA

Valentine G. Nenajdenkov

Moscow State University

Department of Chemistry

Leninskie Gory

119991 Moscow

Russia

Ricardo A.W. Neves Filho

Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry

Department of Bioorganic Chemistry

Weinberg 3

06120 Halle (Saale)

Germany

Roeland J.M. Nolte

Radboud University Nijmegen

Institute for Molecules and Materials

Heyendaalseweg 135

6525 AJ Nijmegen

The Netherlands

Tetsuo Okujima

Ehime University

Graduate School of Science and Engineering

Department of Chemistry and Biology

2-5 Bunkyo-cho

Matsuyama 790-8577

Japan

Noboru Ono

Kyoto University

Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS)

Nishikyo-ku

Kyoto 615-8510

Japan

Romano V.A. Orru

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Department of Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences

De Boelelaan 1083

1081 HV Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Armando J.L. Pombeiro

Technical University of Lisbon

Centro de Química Estrutural

Instituto Superior Técnico

1049-001 Lisbon

Portugal

Rosario Ramón

Barcelona Science Park

University of Barcelona

Baldiri Reixac 10-12

08028 Barcelona

Spain

Renata Riva

Università a degli Studi di Genova

Dipartimento di Chimica e Chimica Industriale

Via Dodecaneso 31

16146 Genova

Italy

Daniel G. Rivera

Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry

Department of Bioorganic Chemistry

Weinberg 3

06120 Halle (Saale)

Germany

and

Faculty of Chemistry

University of Havana

Center for Natural Products Study

Zapata y G

10400 La Habana

Cuba

Alan E. Rowan

Radboud University Nijmegen

Institute for Molecules and Materials

Heyendaalseweg 135

6525 AJ Nijmegen

The Netherlands

Eelco Ruijter

VU University Amsterdam

Department of Chemistry & Pharmaceutical Sciences

De Boelelaan 1083

1081 HV Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Afshin Sarvary

Shahid Beheshti University

Department of Chemistry

G. C. P. O. Box 19396-4716

Tehran

Iran

Ahmad Shaabani

Shahid Beheshti University

Department of Chemistry

G. C. P. O. Box 19396-4716

Tehran

Iran

Ludger A. Wessjohann

Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry

Department of Bioorganic Chemistry

Weinberg 3

06120 Halle (Saale)

Germany

Alexander G. Zhdanko

Moscow State University

Department of Chemistry

Leninskie Gory

Moscow 119991

Russia

1

Chiral Nonracemic Isocyanides

Although isocyanides have proven to be very useful synthetic intermediates – especially in the field of multicomponent reactions – most research investigations performed to date on isocyanides have involved commercially available, unfunctionalized and achiral (or chiral racemic) compounds. Two reasons can be envisioned for the infrequent use of enantiomerically pure isocyanides: (i) the general lack of asymmetric induction produced by them; and (ii) the high tendency to lose stereochemical integrity in some particular classes of isonitriles. However, it is believed that when these drawbacks are overcome, the use of chiral non-racemic isocyanides in multicomponent reactions can be very precious, allowing a more thorough exploration of diversity (in particular stereochemical diversity) in the final products. Recently, several reports have been made describing the preparation and use of new classes of functionalized chiral isocyanides. In fact, several chiral isocyanides may be found in nature, and these will be briefly described in Section 1.5, with attention focused on their total syntheses. Another growing application of chiral isocyanides is in the synthesis of chiral helical polyisocyanides.

It is hoped that this review will encourage chemists first to synthesize a larger number of chiral isocyanides, and subsequently to exploit them in multicomponent reactions, in total synthesis, and in the material sciences.

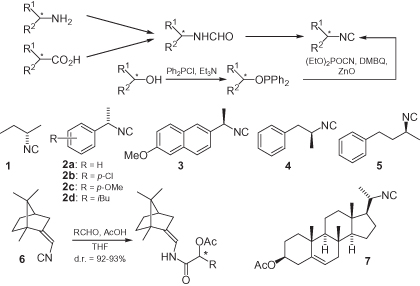

The standard method used to prepare chiral isocyanides (whether functionalized, or not) begins from the corresponding amines, and employs a two-step sequence of formylation and dehydration (). Many enantiomerically pure amines are easily available from natural sources, classical resolution [1], or asymmetric synthesis. Formylation is commonly achieved via four general methods: (i) refluxing the amine in ethyl formate [2]; (ii) reacting the amine with the mixed formic–acetic anhydride [2]; (iii) reacting the amine with formic acid and DCC (dicyclohexylcarbodiimide) [3] or other carbodiimides [4]; and (iv) reacting the amine with an activated formic ester, such as cyanomethyl formate [5], p-nitrophenyl formate [6], or 2,4,5-trichlorophenyl formate [7]. For the dehydration step, several reagents are available, with the commonest and mildest methods involving POCl3, diphosgene, or triphosgene at low temperatures in the presence of a tertiary amine [2]. Although less commonly used, Burgess reagent (methyl N-(triethylammoniumsulfonyl)carbamate) [8] and the CCl4/PPh3/Et3N system [7] have also been employed.

Alternatively, formamides can be obtained from chiral carboxylic acids, through a stereospecific Curtius rearrangement followed by reduction of the resulting isocyanate [9, 10].

Isocyanides may also be prepared from alcohols, by conversion of the alcohol into a sulfonate or halide, followed by SN2 substitution with AgCN [11]; however, this method works well only with primary alcohols. In contrast, a series of chiral isocyanides have been synthesized from chiral secondary alcohols via a two-step protocol that involves conversion first into diphenylphosphinite, followed by a stereospecific substitution that proceeds with a complete inversion of configuration [12]. The substitution step is indeed an oxidation–substitution, that employs dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone (DMBQ) as a stoichiometric oxidant and ZnO as an additive. Alternatively, primary or secondary alcohols can be converted into formamides through the corresponding alkyl azides and amines.

Some examples of simple chiral isocyanides are shown in . These materials have all been prepared in a traditional manner, starting from chiral amines; the exception here is 5, which was synthesized from the secondary alcohol. The compounds comprise fully aliphatic examples such as 1 [13], α-substituted benzyl isocyanides such as 2 [1, 2, 13, 14] and 3 [14, 15], and α-substituted phenethyl or phenylpropyl isocyanides such as 4 [2] and 5 [12].

Because of the great synthetic importance of isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions, these chiral isocyanides have been often used as inputs in these reactions. The use of enantiomerically pure isocyanides can, in principle, bring about two advantages: (i) the possibility to obtain a stereochemically diverse adduct, controlling the absolute configuration of the starting isonitrile; and (ii) the possibility to induce diastereoselection in the multicomponent reaction. With regards to the second of these benefits, the results have been often disappointing, most likely because of the relative unbulkiness of this functional group. For example, Seebach has screened a series of chiral isocyanides, including 2a and 4 in the TiCl4-mediated addition to aldehydes, but with no diastereoselection at all [2]. This behavior seems quite general also for the functionalized isocyanides described later, the only exception known to date being represented by the camphor-derived isocyanide 6 [16], which afforded good levels of diastereoselection in Passerini reactions. The same isonitrile gave no asymmetric induction in the corresponding Ugi reaction, however. Steroidal isocyanides have also been reported (i.e., 7) [17, 18].

Apart from multicomponent reactions, and the synthesis of polyisocyanides (see Section 1.6), chiral unfunctionalized isocyanides have been used as intermediates in the synthesis of chiral nitriles, exploiting the stereospecific (retention) rearrangement of isocyanides into nitriles under flash vacuum pyrolysis conditions (FVP) [14, 19]. This methodology was used for the enantioselective synthesis of the anti-inflammatory drugs ibuprofen and naproxen, from 2d and 3, respectively. As isocyanides are usually prepared from amines, the overall sequence represents the homologation of an amine to a carboxylic derivative, and is therefore opposite to the Curtius rearrangement.

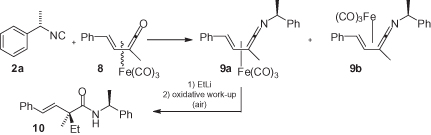

Another interesting application of 2a, as a chiral auxiliary, was reported by Alcock et al. (). Here, the chiral isocyanide reacts with racemic vinylketene tricarbonyliron(0) complex 8 to produce two diastereomeric (vinylketeneimine)tricarbonyliron complexes 9 that can be separated. Subsequent reaction with an organolithium reagent, followed by an oxidative work-up, was found to be highly diastereoselective, forming only adduct 10. This represents a useful method for accessing quaternary stereogenic centers, with the induction being clearly due to the tricarbonyliron group, while the isocyanide chirality serves only as a means of separating the two axial stereoisomers 9a and 9b [15].

As the reactivity of α-isocyano esters and amides is reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4 of this book, attention at this point will be focused only on stereochemical issues; reactions exploiting reactivity at the α position will not be described.

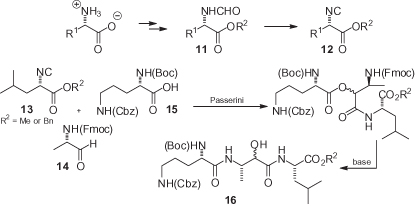

Enantiomerically pure α-isocyano esters 12 can be prepared by the dehydration of formamides 11, which in turn are synthesized in two steps from the corresponding α-amino acids [20, 21] (). The most critical step is dehydration, which has been demonstrated in some instances to be partly racemizing. The combination of diphosgene with N-methylmorpholine (NMM) at a low (<−25 °C) temperature has been reported in various studies to be able to avoid racemization and to be superior to the use of POCl3 with more basic amines [2, 22–25]. In a recent extensive study, the use of triphosgene/NMM at −30 °C was suggested as the method of choice [26], although a direct comparison of triphosgene with diphosgene was not carried out.

These isocyanides would be very useful in multicomponent reactions, such as the Passerini and Ugi condensations, for the straightforward preparation of depsipetides or peptides, although racemization may be a relevant issue. Under Passerini conditions, these compounds appear to be configurationally stable during reaction with various aldehydes [22, 27–29], and this approach has been used, for example, in the total synthesis of eurystatin A [22] (). The quite complex tripeptide 16 has been assembled in just two steps by using a PADAM (Passerini–Amine Deprotection–Acyl Migration) strategy [30], starting from three enantiomerically pure substrates 13, 14, and 15. Once again, none of the three chiral inputs was able to induce any diastereoselection, but at least three of the four stereogenic centers could be fully controlled by the appropriate substrate configurations. α-Isocyano esters are also configurationally stable during the TiCl4-mediated condensation of isocyanides with aldehydes [2].

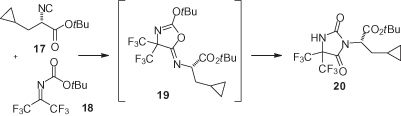

With ketones, the Passerini reaction is slower such that some degree of racemization may occur, depending on the carboxylic acid employed [31]. Chiral α-isocyano esters have been used also in the synthesis of optically active hydantoins such as 20 () [5]; however, the enantiomeric purity was not precisely assessed, and it could not be ascertained if these conditions were racemizing, or not.

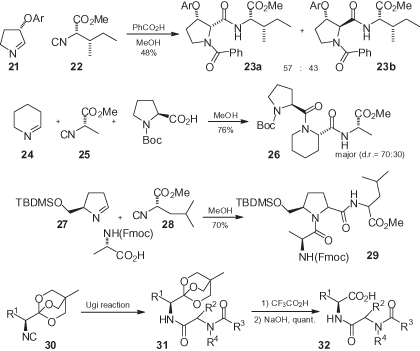

In contrast, the conditions of the Ugi reaction are often incompatible with the stereochemical integrity of chiral α-isocyano esters [20, 25, 32]. A careful study of reaction conditions has shown that – at least for the reaction with ketones – racemization can be almost completely suppressed by carrying out the reaction in CH2Cl2 with BF3·Et2O as catalyst [25]. In this case, racemization is believed to be provoked by the free amine; in fact, α-isocyano esters will readily racemize when treated with amines at room temperature (r.t.) [2]. On this basis, the use of preformed imines would be expected to be capable of preventing racemization, although such success was stated only in few cases, that always involved preformed cyclic imines (). For example, Joullié has reported the formation of only two diastereomers 23 in the condensation of chiral imine 21 with chiral isocyano ester 22 [33]. Similarly, Sello has obtained only two diastereomers in the condensation of achiral imine 24 with chiral isocyanide 25 and Boc-proline. Interestingly, the two diastereomers have been obtained in 70 : 30 ratio [34]; this was unusual since, in most cases, chiral isocyanides and chiral carboxylic acids provide no stereochemical control in Ugi reactions. The absence of racemization in Ugi–Joullié reactions is not general. Rather, the present authors experienced the formation of four diastereomers in the reaction of chiral pyrroline 27 with leucine-derived isocyano ester 28 [24].

An ingenious approach to avoid these racemization issues was recently devised by Nenajdenko and coworkers [35], who employed orthoesters 30 as surrogates of α-isocyano esters. After the Ugi reaction, which proceeds with no racemization, the free carboxylic acids 32 could be obtained in quantitative yield via a two-step/one-pot methodology.

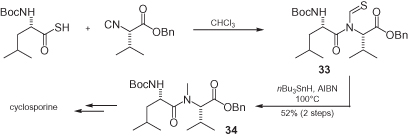

A non-multicomponent application of chiral α-isocyano esters was recently developed by Danishefsky, who created a general method for the synthesis of N-methylated peptides, a moiety which is present in many important natural substances, such as cyclosporine [36] (). The coupling of an isocyano ester with a thioacid produces a thioformyl amide that can be conveniently reduced by tributyltin hydride, with the overall sequence taking place without racemization.

α-Isocyano esters can provide a variety of reactions involving enolization at the α positions (these are reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4). Whilst deprotonation clearly brings about the loss of the stereogenic center, if chirality is present elsewhere (e.g., in the alcoholic counterpart of the ester), then asymmetric induction is, in principle, viable. To date, very few α-isocyanoacetates of chiral alcohols have been prepared [37, 38], and their efficient application in asymmetric synthesis has never been reported [21].

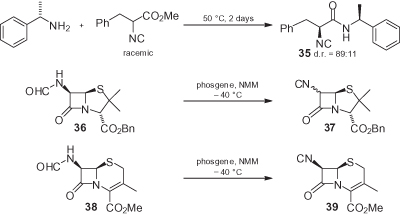

Although, in principle, chiral α-isocyano amides can be prepared by the reaction of α-isocyano esters with amines, the easy racemization of the latter compounds under basic conditions makes this approach unfeasible. By using chiral enantiomerically pure amines, it is even possible to realize a dynamic kinetic resolution of racemic α-isocyano esters, obtaining α-isocyanoamides in good diastereomeric ratios, as in the case of compound 35 [2] (). Due to the lower α-acidity, the stereoconservative preparation of chiral α-isocyano amides from the corresponding formamides is less problematic than that of the corresponding esters, and combinations of POCl3 with Et3N may also be used. The only exception here is represented by penicillin- or cephalosporin-derived isocyanides [6]. Cephalosporin-derived isocyanide 39 can be obtained without epimerization, but only when weaker NMM is used as the base (with Et3N, extensive epimerization takes place). On the other hand, with penicillin-derived formamide 36 a near to 1 : 1 epimeric mixture is obtained, even with NMM.

α-Isocyano amides are also less prone to racemize during multicomponent reactions, although in this case the yields may be impaired by concurrent oxazole formation [24, 39] (see Chapter 3).

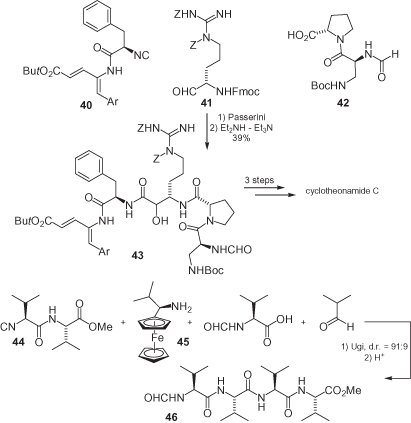

Nonetheless, α-isocyanoamides have been employed successfully in both the Passerini [27, 40] and Ugi reactions [41], some representative examples of which are shown in . Aitken and Fauré have accomplished a highly convergent synthesis of cyclotheonamide C by exploiting the above-cited PADAM strategy [30], and using three polyfunctionalized substrates, namely α-isocyano amide 40, protected α-amino aldehyde 41, and protected amino acid 42 [40]. Despite none of these three chiral substrates being capable of affording any stereoselection, this is unimportant because the new stereogenic center is later lost by oxidation. Ugi et al. have demonstrated the applicability of their reaction in the straightforward synthesis of tetrapeptide 46 [41] although, in this case, two problems had first to be resolved: (i) the poor asymmetric induction provided by both the chiral isocyanide and the carboxylic acid; and (ii) the need for secondary amides (the use of ammonia is often inadequate in Ugi reactions). Ultimately, both issues were resolved by using the chiral ferrocenyl auxiliary 45, which afforded a good stereoinduction and could easily be removed under acidic conditions.

The α-isocyano amides may also provide a wide variety of stereoselective reactions that involve enolization at the α positions, provided that chirality is present in the amine counterpart. Consequently, various chiral α-isocyano amides have been prepared [6, 42–46], some of which have provided good levels of diastereoselectivity [6, 42, 45, 46] (these reactions are reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4).

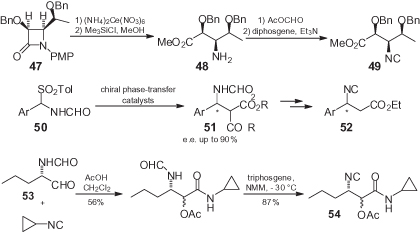

The β-isocyano esters are not expected to suffer from the racemization issues of their α counterparts, and may be very valuable inputs for the multicomponent assembly of peptidomimetics. Somewhat surprisingly, however, very few reports have been made on this class of compound, most likely because of the limited availability of enantiomerically pure β-amino acids (). Previously, Palomo et al. [47] have successfully prepared β-isocyano esters such as 49 through an opening of the β-lactam 47, which in turn was stereoselectively accessed by the Staudinger condensation of a lactaldehyde imine. Although this approach may represent a fairly general entry to these isocyanides, its potential has not been further exploited, and the isocyanide 49 has been used simply as an intermediate for deamination procedures.

Within the present authors’ group, a general organocatalytic entry to β-isocyano esters of general formula 52 in both enantiomeric forms has recently been identified. While N-formyl imines have been demonstrated to be unstable, they can be generated in situ from sulfonyl derivatives 50 under phase-transfer conditions. Subsequently, the use of quinine- or quinidine-derived catalysts allowed, after careful optimization, malonates 51 to be obtained in both enantiomeric forms, with enantiomeric excess (e.e.) values ranging between 64% and 90%. Moreover, the yields were almost quantitative and the e.e.-values could be brought to 98% by crystallization. Subsequently, malonates 51 have been converted in high yields into isocyanides 52 by decarboxylation and dehydration (F. Morana, et al., unpublished results).

During the total synthesis of the antiviral agent telaprevir, Orru and Ruijter have recently reported an interesting approach (that in principle may be general) for the synthesis of protected α-hydroxy-β-isocyano esters such as 54, based on the Passerini reaction of a chiral α-formylamino aldehyde 53 [48]. The only drawback of this methodology is the low stereoselection of the Passerini reaction, though this is not influential if the targeted products are peptidomimetic and contain the α-keto-β-amino amide transition state mimic.

Sulfonylmethyl isocyanides are synthetic equivalents of formaldehyde mono- or di-anions, and have found several useful applications. Chiral derivatives can, in principle, be used for achieving asymmetric induction, with Van Leusen and colleagues having prepared a series of chiral analogues with either stereocenters in the group attached to sulfur (i.e., 55) or with a stereogenic sulfur atom (56) (). These chiral p-toluenesulfonylmethyl isocyanide (TosMIC) analogues were tested in the synthesis of cyclobutanones [49] or oxazolines [50]. In the latter case, two trans diastereomers (57a and 57b) were usually obtained, and the best results in terms of stereoselectivity were obtained with sulfonimide 56 (diastereomeric excess (d.e.) = 80%). The preparation of enantiomerically pure sulfonimide 56 is not trivial, however. Oxazolines 57 can be hydrolyzed to α-hydroxyaldehydes 58.

Van Leusen has also prepared the chiral phosphonylmethyl isocyanide 61 (as well as its trans epimer), starting from enantiomerically pure dioxaphosphorinane 59 [51]. Here, the key step is an Arbuzov reaction of 59 with a N-methylformamide equipped with a good leaving group. It is worth noting that this represents an unconventional formamide synthesis, that does not proceed through a primary amine.

A series of protected chiral β-amino isocyanides of general formula 63 has been prepared in enantiomerically pure form via two general strategies (). The first strategy begins with protected α-amino acids and involves transformation into the nitriles, reduction, formylation, and dehydration [52]. The second strategy [10] is considerably shorter, but starts from less readily available β-amino acids that are converted in a one-pot reaction, via a Curtius rearrangement, into the same formamides 62. These isocyanides have been used in the cycloaddition with trimethylsilyl azide to produce tetrazoles 65 [10], and also in the synthesis of isoselenocyanates 66 and selenoureas [52].

A few chiral γ-isocyano amines are also known [10]. For example, compounds 67 have been obtained by the reaction of chiral N-tosyl aziridines with α-lithiated benzyl isocyanides [53], though the reaction is poorly stereoselective and two separable diastereomers were obtained. Likewise, the complex nucleosidic γ-amino isocyanide 68 has been prepared as an advanced intermediate in the convergent total synthesis of muraymicyn D2, and used as input in an Ugi reaction with a chiral carboxylic acid and achiral aldehyde and amine [54]. No asymmetric induction was observed, however.

Whereas, the use of isocyanides in the Ugi reactions leads to peptide-like structures, the Huisgen cycloaddition of azides and alkynes produces triazoles, which are also deemed as peptide surrogates. Consequently, the incorporation of both an isocyanide and an azide into the same building block represents a valuable strategy to build up peptidomimetics in a very convergent manner [55]. Compounds 71 () have been prepared from β-formamido alcohols 69, in turn obtained from α-amino acids; in this case, a one-pot mesylation–dehydration step provided the sulfonate 70, which was then substituted by sodium azide. These isocyanides are configurationally stable under either Ugi or Passerini conditions. An example of an application featuring a tandem Ugi–Huisgen protocol is shown in where, as usual, no asymmetric induction by the chiral isocyanide was noted in the Ugi step.

β-Hydroxy isocyanides 76 or their protected derivatives 75 represent very useful synthons for the synthesis of peptidomimetic structures through multicomponent reactions (). Compounds 76 have also been prepared as potential anti-AIDS drugs (i.e., nucleoside mimics with reverse transcriptase inhibitory activity) [56]. For R2 = R3 = H, the alcoholic function can be later oxidized, making 75–76 synthetically equivalent to easily racemizable α-isocyano esters or the likely unstable α-isocyano aldehydes [57].

For R2 = R3 = H, formamides 74 can be easily obtained in two steps from α-amino acids, whereas α- or α,α′-substituted derivatives have been obtained through longer routes [58, 59]. As the direct conversion of 74 into isocyanides 76 was reported to be troublesome [59], the best route seems to involve a temporary protection of 74 to produce 75a or 75b, followed by dehydration and finally deprotection with BF3·Et2O (75a) [59] or nBu4NF (75b) [56]. However, when R2 and R3 are different from hydrogen [59], or if the Burgess reagent is employed [8], then dehydration to 76 can be carried out directly on 74. One of the main uses of compounds 76 is the two-component synthesis of oxazolines 77 by reaction with aldehydes. This reaction displays no stereoselectivity, and consequently oxazolines 77 are obtained as a 1 : 1 separable mixture of diastereomers that have been used as bidentate chiral ligands in the asymmetric diethylzinc addition to aldehydes [60].

In contrast, the protected isocyano alcohols 75c and 75d have been employed in classical Passerini [61] and Ugi reactions [57, 62] although, again, no stereoselection was observed. Compounds 75d have also been submitted to the isocyanide–cyanide rearrangement under FVP conditions to produce β-acetoxy nitriles [19]. Finally, 75e has been employed in the synthesis of formamidines which have, in turn, been used as chiral auxiliaries [63].

Alcohols 76 are not very stable, and must be conserved at low temperatures or used immediately after their preparation, because they tend to be converted into unsubstituted oxazolines 78. This cyclization may be reverted under strong basic conditions to produce the conjugate bases of 76, that have been exploited for the preparation of pseudo-C2-symmetric ligands 79 [58, 64]. These ligands have found various applications in organometal catalysis; for example, iron(II) complexes have recently been used in the asymmetric transfer hydrogenations of aromatic and heteroaromatic ketones [58].

A general approach to γ-isocyano alcohols is represented by the biocatalytic desymmetrization of 2-substituted 1,3-propanediols, followed by the substitution of one of the two hydroxy functions with the isocyanide, through the corresponding azides and formamides (). The synthetic equivalence of the two hydroxymethyl arms allows the enantiodivergent synthesis of both enantiomeric isocyanides, starting from the same monoacetate. The present authors’ group has recently prepared both enantiomers of a series of isocyanides 80 and 81 by this strategy, and used them in stereoselective Ugi–Joullié coupling with chiral imines [65]. The nucleosidic γ-isocyano alcohol 83 has been prepared, again by reduction, formylation, and dehydration from azido alcohol 82, in an attempt to identify potential anti-AIDS drugs, such as azidothymidine (AZT) analogues [7].

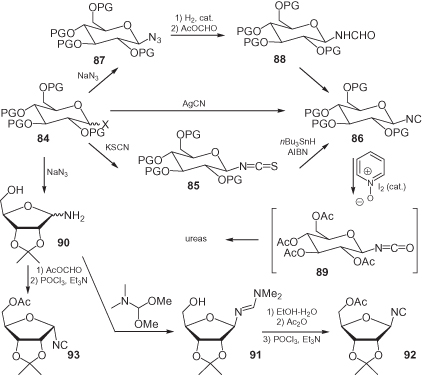

Previously, several isocyano sugars have been synthesized, with the isocyanide either being bound to the anomeric positions, or not. Glycosyl isocyanides, such as 86 (), may be prepared starting from fully benzylated glycosyl halides 84 by reaction with silver cyanide [66], with the β-anomer usually being favored. A more efficient methodology, that is also more compatible with fully acetylated glycosyl halides, involves the initial transformation into the isothiocyanate 85, followed by a controlled radical reduction with nBu3SnH initiated by azo-bis-isobutyronitrile (AIBN) [67].

Alternatively, glycosyl isocyanides may be prepared by a longer (but often more stereoselective) route that involves the formation of a glycosyl azide 87, followed by reduction, formylation, and dehydration [68, 69]. A shorter route, which allows the preparation of both anomers, has been developed in the field of pentofuranoses (ribosyl isocyanides are shown as an example) [70]. The treatment of protected ribofuranosylamine 90 with the mixed acetic formic anhydride affords directly the α formamide, with concomitant acetylation of the 5-OH; dehydration then yields α isocyanide 93. In contrast, when 90 is converted into the amidine 91, only the β-anomer is formed. A careful hydrolysis produces a β-formamide that, upon acetylation and dehydration, leads to the β-isocyanide 92.

The main application of glycosyl isocyanides relies on their transformation into isocyanates such as 89, en route to ureido-linked disaccharides or sugar-amino acid conjugates [68, 71, 72]. These isocyanides have also been converted into amidines [73].

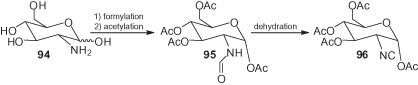

In contrast, 2-deoxy-2-isocyano sugars have been synthesized starting from the corresponding 2-deoxy-2-aminosugars (glucosamine, galactosamine) () [74]. Thus, glucosamine 94 was formylated to produce (after peracetylation of the hydroxy groups) formamide 95, which was then either directly dehydrated to 96 or first activated and coupled with various glycosyl acceptors, and later dehydrated, affording isocyano disaccharides [75, 76]. In each of these cases the isocyano group was finally reductively (nBu3SnH) removed. Thus, its ultimate function was simply an elimination of the amino group in order to obtain 2-deoxysugars.

Surprisingly, despite the excellent chemistry that has been developed for their synthesis, these sugar isocyanides have to date been employed only very rarely in multicomponent reactions (some examples are depicted in ). Ziegler has reported a series of Ugi and Passerini reactions of glycosyl isocyanides such as 97 [69], while Beau and again Ziegler have reported Ugi and Passerini reactions of 2-isocyano sugars such as 96 [77]. The yields of these reactions are not very high although, in general, glycosyl isocyanides behave better than 2-isocyano sugars. Among the latter compounds the bulkier α-anomers function worse, often giving rise to sluggish reactions. Finally, the Passerini condensations afford better yields than their Ugi counterparts, and in all cases – even when chiral aldehydes have been used – the stereoselectivity was very poor; that is, the diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) never was >60 : 40).

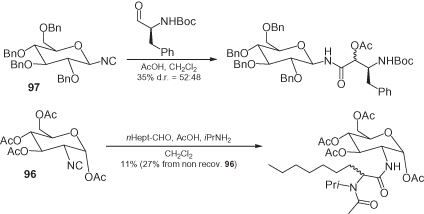

This topic has been widely examined, and information obtained up to mid 2003 has been included in three excellent reviews [78–80]. Interestingly, the first naturally occurring isocyanide, xanthocillin 98 (), was isolated only in 1957 from a culture of Penicillium notatum, but this is not a chiral compound. The first enantiomerically pure isocyanide, axisonitrile-1 99, was isolated and characterized only in 1973 [81]. In general, these compounds have been identified in marine invertebrates, such as sponges and nudibranch mollusks, and less frequently in fungi or cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). Natural isocyanides are often accompanied by the corresponding isothiocyanates and formamides – compounds that have been shown as being biogenetically related. In natural chiral isonitriles, the isocyano group is in most cases attached directly to the stereogenic center which is, in turn, a tertiary or often a quaternary carbon.

Examples of natural isocyanides.

Marine derivatives display almost exclusively a terpene-derived skeleton (sesqui- or diterpenes) and, in some cases, also interesting biological properties, such as anti-malarial activity, antibiotic properties, and cytotoxicity. On the contrary, compounds isolated from cyanobacteria have rather complex alkaloid structures, whereas to date very few examples of natural isocyanides in the field of macrolides or carbohydrates have been reported [82, 83].

During the past eight years, only a limited number of new isocyanides have been isolated, among which three compounds are worthy of mention: 100, a copper(I) complex [84]; 101, with a unique lipidic arrangement [85]; and 102, one of the few examples of structures which bear simultaneously an isocyanide and a formamide function [86].

Among the plethora of total syntheses that have been reported to date, to the best of the present authors’ knowledge only a few dozen are related to the total synthesis of chiral natural isocyanides. These syntheses typically afford enantiomerically pure molecules, although in some instances they may be either enantiomers [87, 88] or epimers [11] of the actual natural compounds. In addition, efficient – but racemic – syntheses have been reported, including the preparation of racemic 99 [89, 90], 103 [91], 104 and its diastereoisomer [92], and 105 [93]. The anti-malarial β-lactam 106 was prepared via a semi-synthesis from another natural substance [94], whereas in the case of 107 only a synthetic approach to the racemic target was reported [95] (). Those compounds which seem to have attracted the most synthetic efforts are the complex hapalindole alkaloids, for which an exhaustive collection of references is available [96]. In essentially all of the synthesized compounds, however, the isocyanide moiety is bound to a stereogenic center (often quaternary), with the exception of 105 [93] and 108–109 [11].

Examples of natural isocyanides that have been the targets of total syntheses.

Typically, the introduction of the isocyanide moiety has been performed as the final step, by dehydration of the corresponding formamide. The only exceptions to this are compounds 106, in which an advanced intermediate already bearing the isocyanide group (146) was used [94], and 108 in which a nucleophilic substitution of an allylic iodide by means of AgCN has been performed at the end of the synthesis (see and , respectively) [11]. Other exceptions are represented by the syntheses of hapaindole derivatives, where often the formation of an isocyanide group is not the last transformation [97]. Hence, on this basis, more attention will be dedicated to these compounds.

A brief survey of the syntheses of enantiomerically pure sesquiterpenes [11, 87, 88, 90, 98, 99] and diterpenoids [91, 94, 95] is reported in .

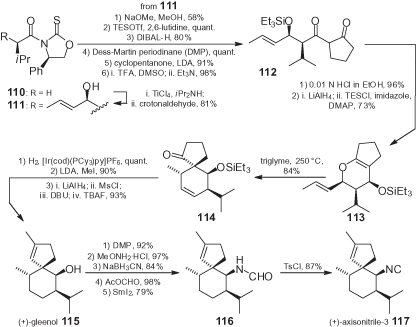

(+)-Axisonitrile-3 117, an anti-malarial compound isolated from the marine sponge Axinella cannabina, was synthesized from chiral oxazolidinethione 110 by exploiting a non-Evans syn-aldol reaction to produce 111 () [99]. After several steps, the key spiranic intermediate (+)-gleenol 115 was obtained through a Claisen rearrangement of dihydropyran 113 to 114, followed by methylation and other simple transformations. The stereoselective conversion of the hydroxy group of 115 into the isocyanide required the oxidation to a ketone, and the introduction of the nitrogen function through a highly diastereoselective reduction of the corresponding O-methyl oxime. The resulting hydroxylamine was formylated, while a reductive cleavage of the N–O bond produced formamide 116 which, eventually, was dehydrated.

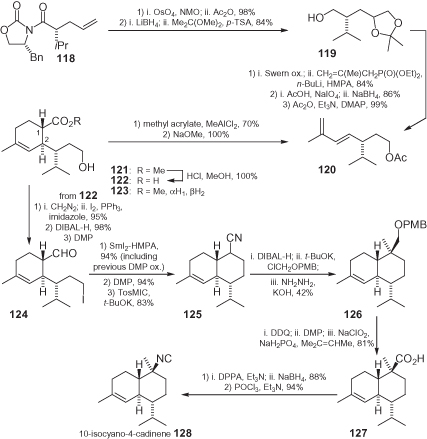

10-Isocyano-4-cadinene 128, a marine sesquiterpene with anti-fouling activity isolated from nudibranchs of the family Phyllidiidae, was prepared from a known allylated oxazolidinone 118, which was the precursor of diene 120 (). Here, the key step is the formation of the cyclohexene moiety with a trans relationship of the 1,2-substituents. The Diels–Alder reaction of diene 120 with methyl acrylate afforded the expected products 121, but as a mixture of four diastereomers. However, equilibration with NaOMe/MeOH gave (apart from cleavage of the acetate) only the trans ester 121 and its trans isomer 123 in a 2 : 1 ratio. The desired acid 122 was finally obtained in pure form by the slow addition of 1 M HCl, followed by selective precipitation; 122 was then transformed into decaline 125 and, via a rather lengthy route, into the carboxylic acid 127. Finally, a Curtius rearrangement (see Section 1.2) allowed production of the formamide precursor of 128, with the isocyanide on a quaternary carbon [98].

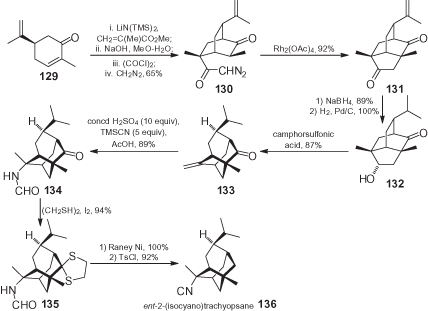

The biomimetic synthesis of ent-2-(isocyano)trachyopsane 136, the enantiomer of a complex tricyclo[4.3.1.03.8]decane which was extracted from the nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa and displayed anti-fouling activity, was achieved from carvone 129 (), which was first transformed into diazoketone 130 by a double Michael reaction, followed by functional group transformations. Isotwistane dione 131, bearing a neopupukeanane skeleton, was obtained through a known regioselective C–H insertion of the corresponding Rh carbenoid. Regioselective and stereoselective reduction to 132, followed by treatment with camphorsulfonic acid, promoted the rearrangement affording trachyopsane 133, an advanced precursor of 136 [88]. The required nitrogen function was introduced stereoselectively through a Ritter reaction, using cyanotrimethylsilane and H2SO4 to yield 134.

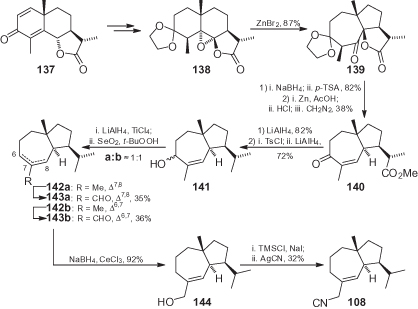

7-Epi-14-isocyano-isodauc-5-ene 108, the epimer of natural 109 extracted from the marine sponge Acantkella acuta, was prepared from natural α-(−)-santonin 137, which was converted into eudesmane derivative 138 by a reported procedure (). This intermediate was submitted to a ZnBr2-mediated rearrangement to give the typical isodaucane skeleton of 139, while subsequent functional group manipulation afforded 141. The reductive removal of allylic hydroxy group afforded an inseparable mixture of the regioisomeric alkenes 142a,b, after which selective oxidation of the allylic methyl group gave alcohols 143a,b. Following separation of the two regioisomers, 143a was finally converted (in moderate yield) into isocyanide 108 by substitution of the corresponding iodide with AgCN [11].

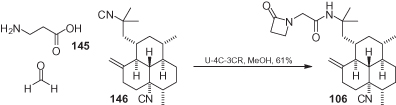

Monamphilectine A 106 is a diterpenoid β-lactam alkaloid that has recently been extracted from the marine sponge Hymeniacidon sp. and shows a potent anti-malarial activity. The synthesis of 106 is the only one in which a multicomponent reaction was employed for a semi-synthetic approach () [94], whereby the β-lactam moiety was introduced through a Ugi four-center, three-component reaction (U-4C-3CR) reacting together β-alanine 145, formaldehyde, and bisisocyanide 146. Interestingly, only one isocyanide group (probably the less-hindered) takes part in the multicomponent reaction.

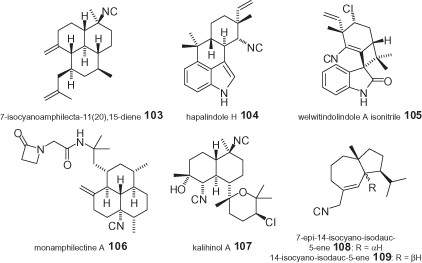

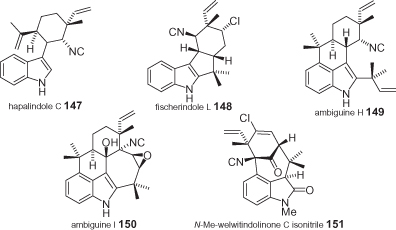

Hapalindole-type natural compounds form a family of over 60 biogenetically related structures that have been isolated from blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) since 1984, and which are characterized by a broad range of biological activities. Typically, they have an indole (and in few cases a fragment derived from the oxidative degradation of the indole) with a monoterpene unit bonded to C3. Most of these compounds have an isocyanide or an isothiocyanate bound (with few exceptions) to a stereogenic carbon that is part of a cyclohexane; moreover, they present in the vicinal position an all-carbon quaternary center (with methyl and vinyl substituents). The tricyclic framework of hapalindole may become either tetracyclic (some hapalindoles, fischerindoles, and some ambiguines) or even pentacyclic (more complex ambiguines). Welwitindolinones may be tetracyclic with a spirocyclic cyclobutanone centered around C3, or they can be characterized by a [4.3.1]bicyclononanone moiety. Some representative examples of their structures are shown in (compounds 104 and 105) and (compounds 147–151) [96, 97, 100].

Structures of some hapalindoles.

Apart from an early report on the synthesis of a hapalindole [101], the most impressive syntheses of these alkaloids in enantiomerically pure form are those reported by Baran’s group [96, 97, 100]. Each of these syntheses is based on a very simple principle: maximize “atom”, “step,” and “redox-economy”, where the latter term indicates a minimization of the superfluous redox manipulations. In this way, the preparation of the target molecule avoids the use of protecting groups and also exploits the natural reactivity of functional groups, such that the basic skeleton can be built on the gram scale.

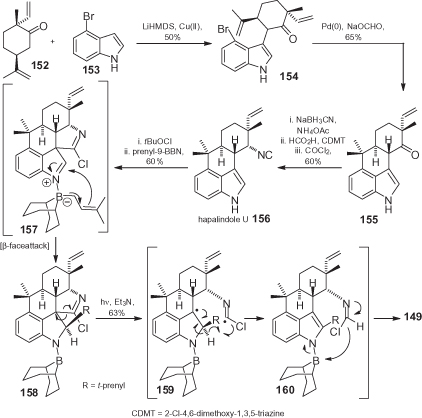

An example of this, the synthesis of ambiguine H 149 and of hapalindole U 156, the precursor of 147 lacking the prenyl unit at C2, is shown in [97]. Here, the intermediate 152, which is readily available from commercial p-menth-1-en-9-ol, was coupled with 4-bromoindole 153 to produce 154, without any need to protect the NH group. The direct Friedel–Crafts annulation on the analogue of 154 (having H instead of Br) was unsuccessful because it was sitoselective on C2 instead of on C4; hence, a switch was made to 154, which allowed the possibility of forcing a formation of the fourth ring in the appropriate position. The desired 6-exo-trig cyclization (reductive Heck) onto C4 to afford 155 was effective when promoted by Hermann’s catalyst. Subsequently, transformation into hapalindole U 156 was accomplished by a reductive amination under microwave heating, followed by conventional introduction of the isocyanide group.

Introduction of the prenyl unit, leading to 149, was the most critical step because direct C–C bond formation was impossible, due to the unusual reactivity of the indole moiety, and to an incompatibility of the isocyanide with acids and transition metals. However, instead of resolving the problem by means of protective groups, the high reactivity of both the indole and the isocyanide was exploited simultaneously by the treatment of 156 with tBuOCl followed by prenyl 9-borabicyclononane (BBN). The electrophilic chlorination of the isocyanide is presumably followed by an addition of the chloronitrilium ion to C3 of the indole, and by coupling of the borane to the indolenine nitrogen to produce 157. Finally, B → C migration yields the crystalline chlorimidate 158, with the t-prenyl group correctly bound at C2. The following Norrish-type homolytic cleavage, promoted by irradiation, furnished eventually ambiguine H 149, most likely through the fragmentation cascade depicted in . Hence, the synthesis of 149 was achieved via a very rapid strategy which fits perfectly with the initial assumptions quoted above.

Atropisomerism, a stereochemical property that is well known in organic chemistry but very rare in polymer chemistry, was first demonstrated in 1974 in polymers of isocyanides [102] (a). In this case, it was shown that poly(tert