Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Background

Focus

Goal and Usage

Problem Seeking and Solving

Chapter 1: Looking Broadly

Looking Broadly

Chapter 2: Interpreting

Interpreting Messages

Chapter 3: Targeting

Targeting Audiences and Responses

Chapter 4: Creating

Creating Visual Messages

Chapter 5: Looking Closer

Looking Closer

Timeline

Modernism

Post-Modernism

Terms

Study Questions

Chapter Concepts

Exercises

Chapter 2 Interpreting

Chapter 4 Creating

Chapter 2 Interpreting

Chapter 3 Targeting

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

Image Credits

Essay

A Lesson from Spirograph

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright © 2011 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Bowers, John, 1959-

Introduction to graphic design methodologies and processes:

understanding theory and application/

John Bowers.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-50435-2 (pbk),

ISBN 978-0-470-95063-0 (ebk),

ISBN 978-0-470-95074-6 (ebk),

1. Design. I. Title.

NC703.B68 2008

760—dc22

2007051392

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the many designers who allowed me to include their work in this edition, including those highlighted in Chapter 5: Antonio Alcalá, Michelle Bowers (no relation), Julie Beeler and Brad Johnson, Sol Sender, and Rick Valicenti. My sincere thanks to Margaret Cummins, senior editor at John Wiley & Sons; Lauren Poplawski, senior editorial assistant; and Doug Salvemini, production editor, for the production assistance; and Karin C. Warren for her help in developing the manuscript. Special thanks to my family, students, colleagues, and friends who gave their support to this project, especially Helene, Jackson, and Sofia.

Introduction

Background

Most graphic designers I know are cautious of graphic design methodologies and processes. They believe formalized approaches are akin to formulas or gimmicks that require little thought, hard work, or regard for the problem at hand. Little has been written on the subject for graphic design students. Yet we all have our own processes and benefit from advancements that are the result of research and methodologies.

Understanding, developing, and applying methodologies and processes can expand possibilities, develop your ideas, and better utilize your abilities. This can lead to work that is original, appropriate, inspiring, and responsible.

My formal education was largely based on developing my intuition through a simple problem-solving approach. While that has served me well, early on I benefited from exposure to design approaches from the Design Management Conference proceedings. Later professional experience at Landor also expanded my interest and understanding. There, I worked alongside consultants who researched specific audiences to achieve desired responses. Since then, I've learned on my own by reading, attending lectures, talking with others, and paying close attention to my own processes.

Profound technological and social changes require designers to be fluent in a variety of approaches to solving problems. As audiences diversify and as information is increasingly accessed and communities shaped by digital means, designers must be able to confront the interconnectedness of problems and society. Methodologies and processes can aid in the understanding of the connections and relationships.

Focus

This book demonstrates and explains how design is shaped by research methodologies and processes as applied to understanding audiences, organizing and using content, developing strategies, and defining purposes. To do this, it emphasizes not only client-associated and user-centered work but also non-client-associated, self-generated work, making a case for the latter as a way of informing the former.

The discussion begins with a section on problem seeking and solving presented as the underlying framework. Chapter 1 takes a broad look at research and introduces the book's issues, while Chapter 5 culminates the discussion through an in-depth focus on select designers' methodologies and processes. Chapters 2 through 4 cover the basics of how research methodologies and processes are applied (interpreting), function (targeting), and execution (creating).

Goal and Usage

Some methodologies and processes are common to all human activity and are used subconsciously, while others require study, practice, and reflection to be used effectively.

Many graphic design methodologies and processes originate or are widely used in other disciplines. For example, Gestalt psychology (the study of how humans perceive form) is the domain of psychology but applied in symbol design. Ethnography research (the study of user patterns) is the domain of anthropology but commonly employed in web design. These methodologies, along with others explored in this book, contribute to defining design as a discipline.

This book will help you:

- Recognize, interpret, and articulate the primary graphic design research methodologies and processes

- Understand, develop, and assess your own methodologies and processes

- Design more strategically, critically, collaboratively, ethically, and creatively for specific audiences, contexts, and responses

Even the best methodology and process cannot ensure good design. Success still depends on your ability to be engaged, to effectively draw from your experience, and to rely on your intuition and innate abilities. Like a well-designed and appropriately used grid, a methodology provides guidance through its conceptual framework.

Problem Seeking and Solving

Humans by nature are seekers of meaning and solvers of problems. We are in a constant search to improve our lives and those of others, and to exercise a degree of control over our interactions and experiences. We have the capacity for reasoning and logical thinking, and thus can make associations, comparisons, and judgments that aid this search.

In the broadest sense, this describes problem solving. A problem in this context is viewed as a challenge and an opportunity, not something to avoid. It is a question raised for consideration and a solution.

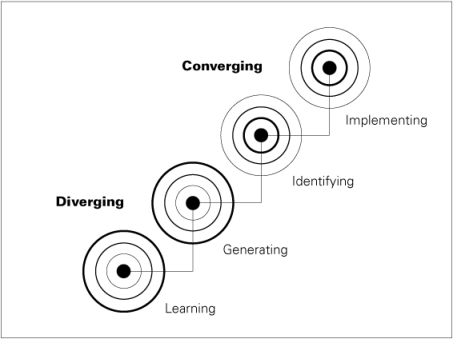

Four basic problem-solving phases are learning, identifying, generating, and implementing. These phases can branch in different directions or be linear or branching—or a combination. Most graphic design activity moves in a branching manner; rarely is the path linear. Reflection, analysis, and evaluation occur at every step.

The four problem-solving phases overlap and may be repeated. Moving backwards is as common as moving forward. The goal is to consider carefully the problem at hand and not reach a solution prematurely.

The problem-solving process diverges and converges, expands and contracts. Divergence is the process of identifying, creating, and developing multiple ways of solving a problem. Convergence is the process of selecting and developing concepts from the previous step's multiple pursuits.

In the learning phase, the process diverges and expands as information is gathered, then contracts as information is analyzed in the identifying phase. The process then again expands in the generating phase as multiple concepts are developed, and contracts in the evaluating phase, in which a single concept is refined, chosen, and implemented. Although each phase has its unique aspects, they can overlap.

Problem Seeking

Increasingly used in education, problem seeking describes non-client-associated, often community-based engagement of an issue (such as sustainability) with an undetermined end form (e.g., from an informational poster to a neighborhood recycling program).

Problem Solving

Problem solving is the cognitive process of engaging an issue or set of conditions for the purpose of transforming it.

Problem-Solving Phases

The basic problem-solving phases of learning, identifying, generating, and implementing can be labeled in different ways.

- Discover

- Invent

- Launch

- Extend (Doblin Group)

- Look

- Learn

- Ask

- Try (IDEO)

Learning

Learning about the conditions that underlie and define a problem is the first step to solving it. This phase is largely conducted with the client and members of a design team. Activities include the following:

- Talking and listening to the client

- Reading about the subject

- Visiting a physical space

- Talking with others informally

- Assembling a design team

- Reviewing and presenting information gathered

Read more about this in Chapters 2 and 5.

Identifying

Identifying the purpose of a project and its different parts, sensibly grouping the parts, and prioritizing them constitute the next step. Goals are established and an underlying concept developed. Activities include the following:

- Interviewing select members of the targeted audience

- Making visual audits of entity and peer groups

- Creating positioning matrices

- Writing a design brief

- Writing, receiving, organizing, and prioritizing content

- Reviewing and presenting information gathered

Read more about this in Chapters 3 and 5.

Generating

- Making thinking maps and visualization matrices

- Generating attribute lists and concept statements

- Creating off-computer sketches, images, and material studies

- Creating on-computer color, font, grid, and typography studies

- Doing on-computer design iterations

- Reviewing and presenting work

Read more about this in Chapters 4 and 5.

Implementing

Implementing and evaluating a solution is the final step. While refinement and evaluation of the solution to meet the project's goals take place throughout the design process, they culminate here and hopefully reinforce earlier decisions. An internal assessment may be done to better understand studio practices. Activities include the following:

- Conducting focus group testing

- Holding usability testing

- Seeking informal feedback

- Placing work in context

- Doing project assessment

- Reviewing work

Read more about this in Chapters 4 and 5.