Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik

Band 21

Herausgegeben von Michael Rebhahn und Thomas Schäfer

Liza Lim

Patterns of Ecstasy

In my formation as a composer, I notice that I have sought out cultural places and practices that arise from epistemological views or ‘ways of knowing’ that recognise a deep interrelationship between realms of the visible and the invisible. Examples include my three operatic works that looked at subjects as diverse as Aeschylus’ ancient Greek drama The Oresteia as a story of unappeased possession; an opera called Yuè Lìng Jié (Moon Spirit Feasting), exploring Chinese shamanic ritual and street theatre, and most recently a chamber opera, The Navigator, which was a study of Eros or structures of desire, obliquely based on Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

Despite the diversity of cultural reference, these works could be described as being about ‘threshold spaces’ where linear narrative coherence gives way to a ritual disjointing and re-jointing of categories of meaning. I have always been attracted to stories that ‘do not add up’. In my most recent opera, I explore the theme or trope of ‘the false sail’ as found in an ancient Breton version of the Tristan story described by poet Anne Caron (1999, p.7): “Tristan lies dying and is waiting for a sign – will a ship appear flying a black sail that indicates disaster (Isolde is dead) or will it be a white sail (Isolde lives)? Tristan is told that a black sail is on the horizon and turns over and dies, but Isolde is in fact on that ship – so what colour was that sail really? Was it black or white? Do we really know what we desire? Can we recognise and meet that which we desire?”

My creative antenna goes up when I encounter this sort of mixture of ambiguity, desire and unknowability, because in such a story, there is so much more to the situation than meets the eye. In this mix-up of terms and meanings, something is hidden, is forgotten or has slipped between the cracks. In that place of slippage, there lies for me an unexposed energy and thus the potential for some kind of transformation or a proliferation of possibilities. In the unknown there is already a script for transcendence.

When I look at the various kinds of ritual forms that I have been interested in, what interests me most is the way ritual constructs a space in which ordinarily invisible forces or phenomena can become visible. That which is unseen, that which exists in an unfixed or ungraspable mode, rises to the surface where it can react in a dynamic way with embodied structures in a defined present temporality to produce meanings. The ‘invisible’ is given visible form whereby it can be dealt with, perhaps propitiated, acknowledged, examined, struggled with and momentarily integrated before being released again.

Over the last five to six years, my compositional work has been informed by an investigation into Australian Aboriginal aesthetics and ritual. In these cultures, a dialectical relationship between the visible and invisible is developed as a central paradigm for structuring the creation of meaning. I am particularly drawn to the intensity of this area of cultural practice as index to an engagement with ‘life force’ or ‘aliveness’, where ritual practice continually refreshes a community’s making and remaking of the world.

I want to digress here slightly to mention that as a non-Indigenous person in Australia, making references to Aboriginal culture (which in any case is not a monolithic construct) often brings up problematic political issues. Given Australia’s brutal colonial history and the continuing inequalities faced by Indigenous people, there are major sensitivities in relation to any kind of cultural transaction in this area. Then there are the particularly mine-laden politics attending cultural protocols within Aboriginal Australia itself in relation to how access to knowledge (or ‘Law’) is controlled or restricted. [In a postscript to this text, and in answer to a question posed by Trevor Baˇca in Darmstadt, I describe how members of an Aboriginal community in a project I was involved in, treated this area of cultural politics in an unexpected and I would say, specifically indigenous way.]

In my own explorations, the question that often arises is: ‘How does one boundary-cross into really different understandings of the world in an ‘authentic’ way?’ (This ‘authenticity’ question is also something I have confronted in relation to my Asian heritage.) Here, I have found it helpful to remember the role of the trickster figure – the trickster energy that is at work in those slippery stories that do not quite make sense. The trickster figure, I think, provides a clue in approaching this question because it turns the idea of ‘authenticity’ on its head – moving away from and disrupting rigid categories of purity and impurity, truth and untruth, where the sacred and profane sit side by side. (Shamanism for instance, is sometime called ‘truthful trickery’ – the power of acting ‘as if’ the impossible were possible from a place of pure presence – Michael Taussig [2006], the writer and anthropologist has written in really interesting ways about this.)

Somehow, perhaps when you insist too much on a truth, you’re also stopping the flow of its energy. To fix the meaning of something also suggests a kind of closure, whereas there is a power in the unstable, stuttering tensions of ambiguity, contradiction and contingency. These are powerful portals through which one can proliferate meaning-making in art.

But what of this power or energy? Does this intensity thereby contain its own authenticity? Why do some things have a peculiar or uncanny force surrounding them? I think this stems not just from a capacity for something to carry multiple interpretations but from a kind of ‘second order’ experience of the uninterpretable – an experience of the meaningful beyond meaning-making. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht (2004) dubs that dimension of uninterpretable feeling experience as ‘presence’ – a sensation of sudden alignment, of intensification and resonance which brings a tangible erotic quality to a situation.

On the subject of ‘intensification’, philosopher Elizabeth Grosz (2008, p. 22) says: “Painting is about rendering the invisible in visible form, and music about sounding the inaudible, each the expression and exploration of the unrepresentable. Art is not the activation of the perceptions and sensations of the lived body … but about transforming the lived body into an unlivable power, an unleashed force that transforms the body along with the world.”

Grosz’ work strongly references Deleuze’s thinking as well as Darwinian theory in an analysis of art’s evolutionary role as an intensification of that which is excess to survival. Together with these thinkers, she roots art ‘not in the creativity of mankind but rather in the superfluousness of nature, in the capacity of the earth to render the sensory superabundant, in the bird’s courtship song and dance, or in the field of lilies swaying in the breeze under a blue sky’ (Grosz, 2008, p.10). She links art and nature as structures of profusion – a play of sensations drawn out of chaos that depart from that which is minimally needed to sustain the utilitarian functioning of life, transforming those forces of chaos and making them available to us in new ways.

The lilies in the field do not ‘mean’ anything but their depth of colour draws us close; the bird isn’t singing ‘about’ something but we might find it stunning. The bird’s song intensifies our perception of that moment in time, that place, and everything around it. In this sense of the charged moment, lies the revelatory, epiphanic quality of aesthetic experience – a sense of the ‘event’ that draws together all the elements (subjects and objects) into a field of interactive experience that is somehow transformative.

This idea of art as transformations of abstracted excess and as play of sensation is enormously appealing to me and I find these qualities of intensification and of revelation, very strongly expressed or prioritised in Aboriginal cultural forms.

Very briefly, in Aboriginal culture, Ancestral time, or to use the popular term, ‘Dreamtime’ is an originary force of creation that underlies all things and can be presenced in all times, mythical, historical and contemporary. Howard Morphy (1998, p. 68) says: “the Dreamtime has never ceased to exist, and from the viewpoint of the present it is as much a feature of the future as it is of the past.” In the Aboriginal worldview, there is a great permeability between temporal structures and this fluctuating nature underpins the structures and expressions of language, ritual and art. In looking at Aboriginal culture, I have focussed particularly on this quality of fluctuation or shimmer.

Shimmer, an effect of flickering light or a pulsing aural quality, has an absolutely central value across Australian Aboriginal cultures as an indicator of the presence of a spiritual reality. The aesthetic quality of shimmer, whether found on a canvas painting, a body painting or the beating of clapsticks, is associated with the creative transformation of matter and a tangible connection to Ancestral time. In Aboriginal visual arts, the qualities of iridescence, of optical effects (think Bridget Riley’s op-art effects) and shiny, bright hues are valued for their suggestion of power and in that suggestion also provides a veil against the full force of that power. The shimmer both reveals and conceals. At the same time, these effects are also often ritually obscured, veiled or made dull in order to further protect onlookers from those same forces (Morphy, 1998, p. 192).

My interest in Aboriginal culture and more specifically Yolgnu culture from Arnhem land in the North-eastern part of Australia became more concrete when I was curating a twilight concert series for the 2006 Adelaide Festival called ‘As night softly falls’. The Yolgnu in this eastern part of Australia are guardians of the light and the old women traditionally ‘sing the light’ on to the land at dawn and away again at dusk. I was researching different traditions that celebrate the ‘changing of the light’ so I wanted to visit these women to find out more about their singing traditions.

Just as I was about to visit this group of women, the key woman cultural leader died.

Nevertheless, I was invited by members of the Yunupingu family of the Gumatj clan to visit her country, a place on the coast called Dhanaya, to attend funeral ceremonies that stretched out over a month. I was there for the final week during which there was a crescendo of ritual performance. On arrival, my first exchange in the ritual camp was to give some of my (straight) hair to make extremely fine paint-brushes that were used to paint the coffin-lid. In exchange, I received mica-flecked red ochre, that is, coloured earth that is used as paint for the body and for bark paintings. I was told to rub the ochre on my skin which became silvery and this was to ‘protect and make me invisible to any bad spirits’ (Ex. 1).

Ex. 1 photos of paint brushes (marawat) made by Merrki Gunambarr out of my hair; in the background there is red ochre in foil packaging.

Photos: Liza Lim

This trade of hair for ochre was an entrée for me to begin to understand something of a cultural economy of hiddenness and a system of revelation of knowledge through hiddenness that is such a strong part of this culture. The element of hiddenness exists for instance, in the language structure of Yolngu matha (the group of languages spoken in Arnhem land). There are many words for, let’s say, a species of snake starting from the ‘outer’/public/ everyday word for that snake to a series of ‘inner’/private/ ritual words that indicate aspects of that creature in increasing proximity to its ancestral spirit meaning. The hierarchy of meanings is an index to greater or lesser permeability to different temporal and spiritual realities. The construction of language and also of knowledge as it is expressed in art is highly multivalent – things are able to hold many levels of interpretation. (see catalogue, Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, 1999)

To give you a glimpse of the complexity of a cultural economy of secrecy-openness, I mention here that often, possession of knowledge and rights to its performance in the broadest sense is gender based. Yet that does not mean that one group for whom a restriction applies does not actually have that knowledge; it may be that they have very different obligations, rights and social-political responsibilities in relation to that knowledge and its distribution (Dussart, 2000, p.59). Secrecy or silence exists at the edges of where different rights and obligations start and finish. Here I am trying to give you a very brief ‘fragrance’ of the status and meaning that terms such as ‘knowledge’, ‘knowing’ and ‘intellectual property’ might have in Aboriginal contexts and how this creates a kind of epistemological ‘texture’ that is quite striking when one is looking from the outside.

For me, coming into contact with Aboriginal cultural systems has resulted in a perspectival shift in my work which for a time was so much based on what I think of as the ‘horizontal’ construction of Chinese knowledge with its cosmologies, writing systems, poetry and other cultural forms having an architecture which might be described as receding ‘courtyards within courtyards’. The horizontal orientation has shifted to a much more vertical idea of structure made up of different layers or depths of transparency/viscosity/opacity. In both cases, the Chinese and the Aboriginal, I am interested in looking at the structures underlying surface effects as a way of coming closer to a specific cultural perspective. There is a process of abstraction, of translation, or an attempt to arrive at the essential qualities that hold the energy patterns of a world-view. Naturally, the result is something quite filtered – a ‘now you see it, now you do not’ kind of trickster’s play with meaning.

In the case of my filtering of Australian Aboriginal aesthetic concepts, I find a way of thinking about structure that is akin to the complex organisation of natural forces like weather, a structure made up of microclimates and dynamical systems in which ideas or hidden forms of knowledge precipitate at different levels. A surface is not a static plane but part of a shifting system which registers ripple effects, shimmering and turbulence patterns from the movement of forces below. In exploring these layered shifting structures, I have particularly focussed on the materiality of sound and the notion of friction as action of repetition as a way of both uncovering and covering up patterns. I have written a series of compositions including solo, chamber and orchestral works centred on an exploration of the aesthetics of shimmer and the shimmer effect that arises from the interactivity of materials and forces.

Invisibility (2009)

One of the things I wanted to explore in my piece Invisibility for solo cello was different levels of interactivity at the material level of the instrument – that is, interactions between the strings, their resonance properties and how the strings are set into motion or stopped using fingers, hand and different kinds of bows. Firstly, I retuned the cello strings so that rather than having the fairly even spread of tension achieved in standard tuning in perfect 5ths (C-G-D-A), the strings display different levels of tension, each string having a distinctive kind of ‘give’ or resistance. The tuning is B (the lowest string dropped by a semitone), F (the next string lowered by a tone), the third string stays the same at D and the highest string is radically detuned down to D-sharp.

Scales of varying resonance qualities are created through degrees of dampening of the string with left hand fingers from light ‘harmonic’ pressure, half-pressure producing in-between muted timbral combinations of pitch/noise, to the resonance of normal finger pressure. At the most muted end of the timbral scale, the palm of the left hand is employed to radically dampen the strings so that one hears the dry brushing of bow strokes with only barest suggestion of pitch. The right hand that wields the bow is also calibrated to bring different gradations of weight or distortion to the strings both vertically and in a lateral direction.

I employ two types of bows to activate the strings – a normal bow and then a second bow which I call a ‘guiro’ bow, after the serrated South American percussion instrument. [The idea for this wrapped bow was conceived by the Australian composer John Rodgers for his work Inferno (2000)]. The bow hair is wrapped around the wood to give an irregular playing surface of alternating materials (hair and wood). The two bows bring different weights and qualities of greater or lesser friction into the equation of how the instrument is sounded. Both bows are employed in standard horizontal and in lateral (sweeping along the string rather than across it) movements. The latter technique creates greater unpredictability for the player in terms of the functioning and control of the bow as it easily ‘glitches’ or catches, interrupting the stroke or slipping off the string (Ex. 2).

Ex. 2 Guiro bow

Photo: Baptiste Zanchi

From the musician’s point of view, how the instrument ‘feels’ under the fingers is quite different – there is more variation than usual with different places of resistance or flow that need to be navigated when playing the music. This physical set-up foregrounds the material or physical aspect of the cello and bow – a more interactive playing surface is created where the cello is not just an instrument that is somehow passively acted upon but it has torque, it has lines of forces that direct how it is to be played. The guiro bow in particular has a playing surface full of unpredictable bumps and edges that create a texture of internal accelerations, awkward slippages and decelerations within every arm movement. In a real sense, the cello and the bow also play the musician and the whole set-up governs the shaping of the musical sounds in a very direct and dynamic way.

The ‘invisibility’ of the title of the piece is not about silence, for the work is full of sounds. Rather, as in Grosz’ and Deleuze’s conception, I am working with an idea of the invisible or latent forces of the physical set-up of the instrument. What emerges as the instrument is sounded in various increasingly rhythmicised ways, is a landscape of unpredictable nicks and ruptures as different layers of action and reaction – speed, tension, pressure of the bows, of fingers and the resistance of the strings – flow across each other.

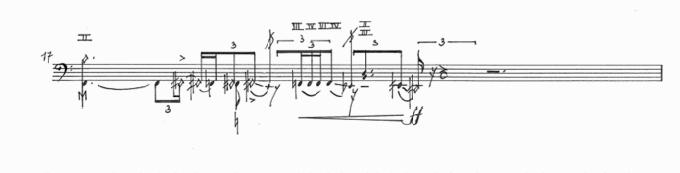

The composition also works with magnifications of these kinds of disruptions by intensifying various paradoxical combinations in relation to string vibration. One example is to lightly touch a string at a non-harmonic node so that the bowed string vibrates in highly complex ways (Ex.3).

Ex. 3 Invisibility, bar 17 (multiphonic sounds on the cello)

© Ricordi, Munich

The first event in bar 17 is an example of a multiphonic sound (marked ‘M’ on the note stem) where the third string, tuned F, is touched at a ‘non-harmonic’ pitch position, in this instance an augmented fourth and octave higher than the open string. When bowed, the string does not settle in any one vibrational zone but flicks or flickers (shimmers) between states so that what results is an unpredictable array of different noises and complex resonances. The result is akin to multiphonic sounds on wind instruments passing through multiple transients.

The passage immediately following the multiphonic mimics the flickering sonic behaviour of the sound by playing with a pitch oscillation around the F. There is the F-sharp harmonic in the second beat sounding the 12th above the B open string which sets up a dissonance against F as reference point, then moving through that point as glissandi in beats three and four. The pitch of B, which is a ghosted presence in the multiphonic, is alluded to through related harmonics of that pitch fundamental (the F-sharp and D-sharp harmonics played on the fourth string).

The use of the guiro bow creates a very particular sonic landscape. The stop/start structure of the serrated bow adds an uneven granular layer of articulation over every sound. Like the cross-hatched designs or dotting effects of Aboriginal art, the ‘guiro’ bow creates a highly mobile sonic surface through which you can hear the outlines of other kinds of movements and shapes. Moving rapidly between places of relative stability and instability in terms of how the cello is sounded, the piece shows up patterns of contraction and expansion, accumulation and dissipation, aligning with or against forces that are at work within the instrument-performer complex.

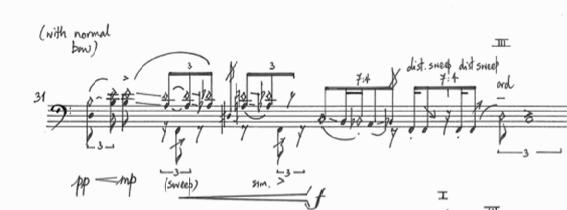

The first part of the piece is performed with the guiro bow and the second part demarcated by the introduction and use of the standard bow. In this second section, the element of repetition or iteration brought to the music by the bumpy surface of the guiro bow is gradually magnified. The action of the standard bow stroke is also disturbed by sudden lateral sweeping movements in a ‘staging’ or magnification of the tendency to slippage and distortion observed in the guiro bow (Ex. 4).

Ex. 4 Invisibility, bar 31 showing slippages (‘sweep’) of the bow

© Ricordi, Munich

The micro-repetitions inherent in each horizontal stroke of the guiro bow are thematised and transformed into more complex figures of repetition. The standard ‘up and down’ of the bow takes in more strings to create great arcs across the body of the instrument. Three or four adjacent strings are sounded in changing combinations with the forwards and backwards movement across open strings (a highly cellistic gesture) allowing the peculiar resistance pattern of the tuning to be foregrounded.

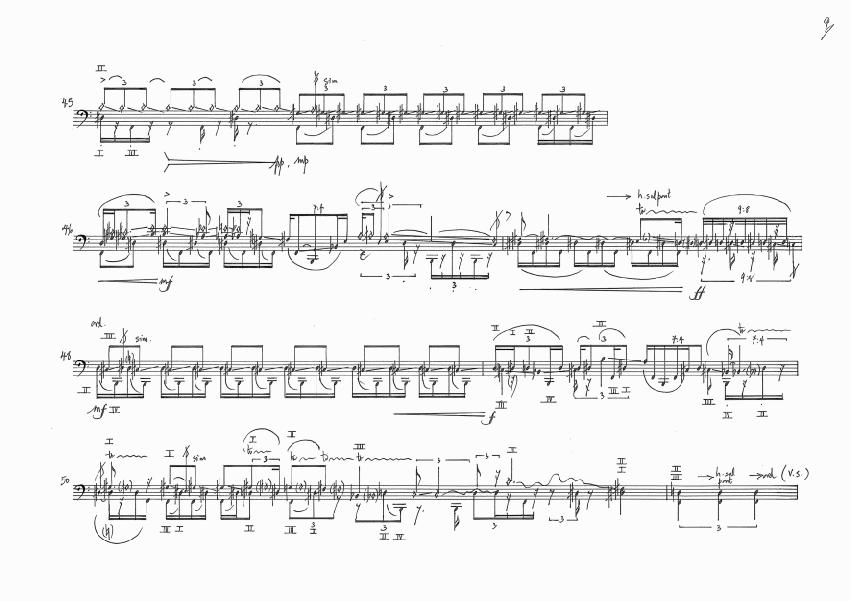

The combination of open string resonance and a counterpoint of sliding motions of nearer and further pitches in relation to those fixed pitch points gives a ‘liquefied’ quality to the texture of repetitions. The repetition establishes a certain stability in the patterning which is then challenged by additional slippages and ‘kinks’ in the texture as the arcing bow catches fragments of alternative resonances created by the sliding and shifting movements on the strings performed in the left hand of the cellist. (Ex. 5).

Ex. 5 Invisibility, page 9

© Ricordi, Munich

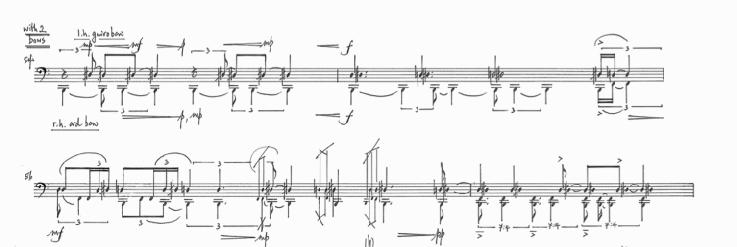

At the close of the work, the two bows, one held in each hand, are used simultaneously to sound the cello. The standard bow is in the right hand and the guiro bow in the left, its surface replacing the left hand’s role in articulating steps in string tension. The guiro bow is used to touch the strings, sliding in repeated glissandi which mimic the repetitive sliding motions in the left hand heard earlier. The guiro bow replaces fingers whilst the standard bow takes on the character of the serrated surface transitioning from hair to wood as it is bounced and then quickly rubbed along the string between the bridge and the fingerboard (Ex. 6).

Ex. 6 Invisibility, bar 58

© Ricordi, Munich

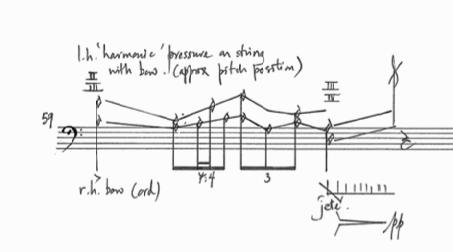

In the following bar, the relatively contained gestures of the repeated glissandi transform into wide sweeping gestures across the strings. The light pressure of the guiro bow takes on the fineness of touch of fingers enabling a complex spray of harmonics to sound (Ex. 7)

Ex. 7 Invisibility, bar 59

© Ricordi, Munich

This final section brings the music to a reduction of the materials to their most basic level (Ex. 8). The two bows stroke the unsuppressed open strings, pushing and pulling across their surface, caressing the instrument from both sides in simple alternating movements. One hears the underlying template of the work laid out as a collection of instrumental resonances and friction sources. And it is here that the work seems most ritualistic in performance. The simplicity of deep resonances imparts a monumental quality to the music whilst one becomes aware of the player’s breathing body in the co-ordinated wing-like movements of the bows crossing from both sides of the instrument (Ex. 9).

Ex. 8 Invisibility, bars 54-57

© Ricordi, Munich

Ex. 9 Photo of Séverine Ballon performing Invisibility

The video of the performance can be found at: http://vimeo.com/13411678

Photo: Rolf Schoelkopf

Pearl, Ochre, Hair String (2010)

Following the composition of this study for solo cello, I used Invisibility as a kind of template for writing a large orchestral work called Pearl, Ochre, Hair String.

Earlier, I talked about ochre (earth colours) and hair as quite central elements in Aboriginal cultural-economic exchange and these are emblematised in the object to which the title refers: the Riji, or pearl shell which is inscribed with navigation patterns that are highlighted on the surface by being rubbed with ochre and then the ensemble completed with string made from human hair (Ex. 10). These carved shells are made in the northern part of Australia and are associated with the initiation of boys but they are also extensively traded across the continent. One theory is that the navigation designs may have been influenced by the interlocking ‘cloud patterns’ found on the Chinese porcelain that was traded between Aboriginal people and the Macassan people from Indonesian islands some 1,000 years before European colonisation. Whilst these carved shells are handled openly by both men and women in the coastal area, in the interior desert parts of Australia, they take on other ritual meanings and are highly sacred items of ‘men’s business’ (Rothwell, 2006). The shells then are objects that carry stories with criss-crossing paths showing how things can take on very different meanings in different contexts and how that meaning is contingent rather than unitary. But certainly, the aesthetic value of the Riji across various sectors of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal society lies in the way meanings are captured in the shimmering iridescence of the biological (the shell), the geological (the coloured earth) and the human enculturation of these elements.

Ex. 10 Aubrey Tigan, 2006, Riji Jakoli (carved pearl shell)

Photo: Liza Lim

Pearl, Ochre, Hair String starts with a solo cello playing with the same kind of guiro bow employed in Invisibility. From here, I expanded this sound world and mode of sound production to create a ‘section of guiros’ made up of the solo cello, the double bass section who bow and tap the strings or their instruments with rasp sticks, and three percussionists playing different kinds of bamboo guiros, reco-recos (the Brazilian samba instrument made out of metal spring-coils that are scraped), Thai wooden ‘frog’ scrapers and a barbeque grill. The fricative qualities of this kind of sound production made up of both ‘solid’ and ‘liquid’ elements – distorted noises and granulated effects contained within a flow of sound – also make their way into how the other instruments of the orchestra are employed. The opening cello solo then is the microcosm of interactive effects and deviations and striations that is intensified within both the guiro section and the larger orchestral environment.

In the orchestral work, I am working with perspectival scales ranging from the micro- to the macroscopic so that aspects of the cello solo are magnified in different ways. The cello source material is the basis for a ‘grammar of granularity’ and in a way, the orchestral work is a restaging of elements of the solo. The work begins with the solo cello using the guiro bow and briefly quotes some material from Invisibility (note that the tuning is different though I have retained the tuning of the lowest string at B; Ex. 11).

Ex. 11 Pearl, Ochre, Hair String, bars 1-3 (cello solo)

© Ricordi, Munich

I then begin to ‘blow up’, to magnify the image of the guiro bow moving over the open B string. I orchestrated this idea by scoring the iterative element of the guiro bow as a muted high timpani playing a B joined by the percussive tick of the temple block which then locks into a ‘late onset’ resonance cloud in wind and brass based on a B overtone series. The micro-level interactions of bow and string are expanded into models for higher level structuring at a larger scale (Ex. 12).

Ex. 12 Pearl, Ochre, Hair String, bars 4-9

© Ricordi, Munich

As in Invisibility, what