| GORDON L ROTTMAN | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

| Consultant editor Martin Windrow |

INTRODUCTION

Organizational history of the US Cavalry, 1865–1918 – the interwar years

PRE-WAR CAVALRY REGIMENTS

Regiments, squadrons, companies and troops – horse cavalry unit organization

WARTIME DISMOUNTED CAVALRY ORGANIZATION

Comparative weakness in manpower and crew-served weapons – wartime augmentations – tactical limitations

26th CAVALRY REGIMENT (PHILIPPINE SCOUTS)

The retreat to Bataan – Morong – Mt Natib

TEXAS NATIONAL GUARD CAVALRY: BACKGROUND

112th CAVALRY REGIMENT (SPECIAL), 1942–OCTOBER 1944

New Caledonia and Australia – Woodlark Island – New Britain – New Guinea

124th CAVALRY REGIMENT (SPECIAL), 1942–45

India – Burma

1st CAVALRY DIVISION (SPECIAL)

Australia – Admiralty Islands – the Philippines: Leyte and Samar – Luzon – Manila – Southern Luzon – occupation of Japan

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Historically, armies are reduced after the end of major wars, but nevertheless the regular US Cavalry was expanded following the Civil War from six to ten regiments. During the opening of the West all ten units were scattered across the vast tracts of country west of the Mississippi. By the late 1880s, with the subjugation of the Native American peoples almost complete, over 90 companies/troops were distributed between 31 posts in the West, averaging two companies/troops per post though with up to four in some cases. While the virtual end of active campaigning did not see the number of regiments reduced, each did lose two companies/troops. The 1898 Spanish-American War saw no increase in the regular cavalry, although a few militia and volunteer units also served. In Cuba the 1st, 3d, 6th, 9th, and 10th Cavalry and the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry (“Rough Riders”) all fought dismounted as infantry. Thereafter the ongoing insurgency in the Philippines led to the authorization in 1901 of the 11th through 15th Cavalry; these too mostly fought dismounted.

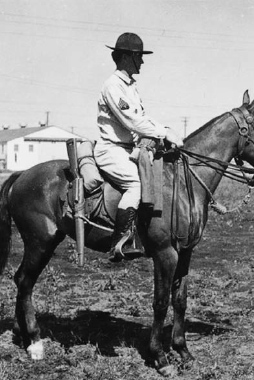

A technician 4th grade, wearing khakis and M1931 lace-up cavalry boots, mounted on the M1928 McClellan saddle. Note the rarely-seen special leather saddle-scabbard for the .30cal M1 carbine. (US Army)

The 16th and 17th Cavalry were activated in 1916. Some regular cavalry regiments served on the Mexican border (as did smaller National Guard units, created from the state militias by the Militia Act of 1903), where their horse-mounted mobility proved valuable. America’s entry into World War I saw the activation of the 18th through 25th Cavalry, but all were immediately converted to artillery, as were the Federalized National Guard cavalry units – cavalry was unnecessary on the Western Front, and it made sense to convert them to horse-drawn artillery. Four regular regiments accompanied the American Expeditionary Force to France, where they provided remount services. At the end of 1917 the 15th Cavalry Division was organized at Ft Bliss, Texas, to have three three-regiment brigades, but only the 1st, 7th, 8th, and 10th Cavalry were actually assigned before the division was inactivated in May 1918.

The introduction of tanks to the battlefield during World War I, coupled with increasing mechanization, the lethality of modern weapons, and the drastically changing nature of maneuver warfare all heralded the beginning of the end for the horse cavalry. The US Cavalry was slow to adopt mechanization, and proponents of horse cavalry sometimes contrived unlikely scenarios in order to justify their retention.

In 1920 two cavalry divisions were authorized, the 1st to be active and the 2d inactive. The division had two two-regiment brigades plus brigade machine-gun squadrons. The 1st Cavalry Division’s assigned regiments were the 1st, 7th, 8th, and 10th, the last being replaced by the 5th in 1922. The division also had a single artillery battalion, an engineer battalion, division trains and HQ, signal, ordnance maintenance, medical, and veterinary companies. In 1933 the 12th Cavalry replaced the 1st Cavalry. The 2d Cavalry Division did not have an active headquarters until April 1940. A “paper” 3d Cavalry Division existed during 1927–40, with the 6th (1927–39), 9th (1933–39), 10th (1927–40) and 11th Cavalry (1927–33); it had no headquarters, and its units were merely administrative assignments. Three cavalry regiments, 15th to 17th, were inactivated in 1921, but the 26th Cavalry (Philippine Scouts) was activated on Luzon in 1922. The remaining regiments were each reduced to two three-troop squadrons along with HQ and service troops, and the machine-gun troop was eliminated. In 1928 the squadrons each lost a troop, but the regimental machine-gun troop was reestablished, with the loss of the brigade machine-gun squadron. Trucks began to replace horse-drawn wagons.

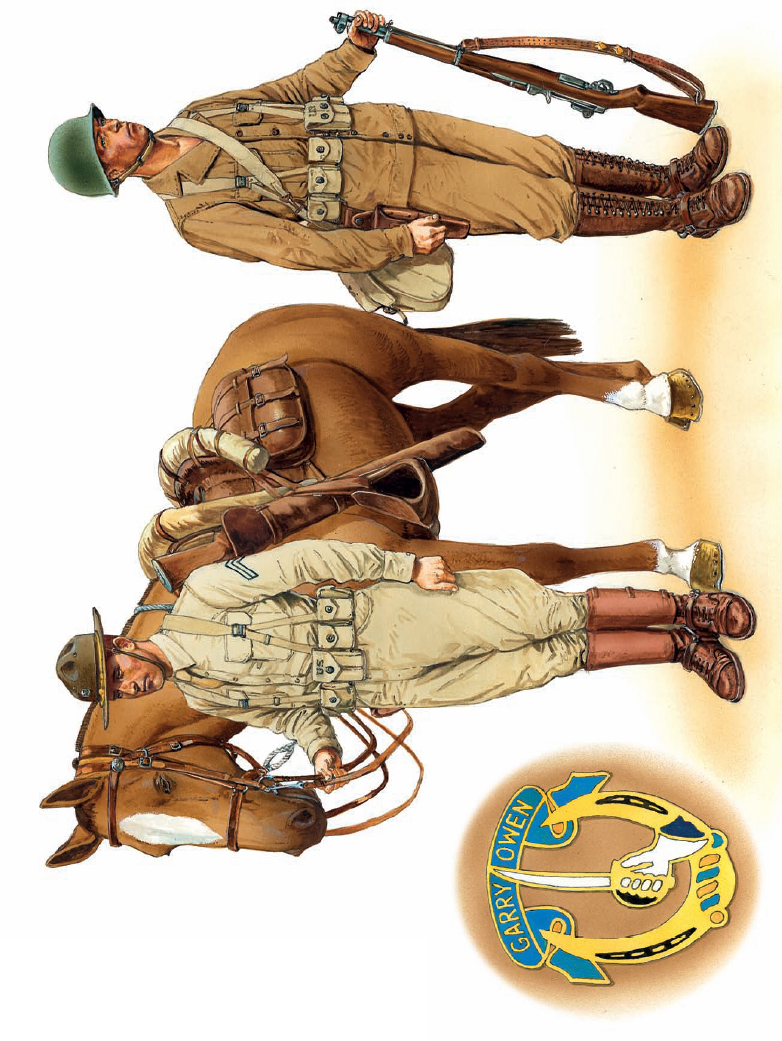

The basic cavalry unit was the eight-man rifle squad. Well into the war it retained an organization of a corporal squad leader, second-in-command, two scouts and four riflemen, all privates and privates first class; two of the riflemen remained in the saddle as horse-holders when the other six dismounted. (US Army)

1st Cavalry Division troopers ride across an open area in a dispersed formation during the August 1940 Louisiana Maneuvers. The Cavalry made a bold effort to demonstrate that it was still viable in modern warfare, but it soon became apparent that horse cavalry, while having its uses, was outmaneuvered by mechanized units. (1st Cavalry Division Museum)

In 1928 the development of armored and mechanized forces in the US Army began in earnest. Some cavalrymen accepted the eventual demise of horse cavalry, but others resisted. The Chief of Cavalry, MajGen John Herr, believed that a mix of horse and mechanized forces was necessary: “We must not be misled to our own detriment to assume that the untried machine can displace the proved and tried horse.” The Army Chief of Staff, Gen Douglas MacArthur, foretold the future of the cavalry: “The horse has no higher degree of mobility today than he had a thousand years ago. The time has therefore arrived when the Cavalry arm must either replace or assist the horse as a means of transportation, or else pass into the limbo of discarded military formations. There is no possibility of eliminating the need for certain units capable of performing more distant missions than can be efficiently carried out by the mass of the Army. The elements assigned to these tasks will be the cavalry of the future, but manifestly the horse alone will not meet its requirements in transportation.”

|

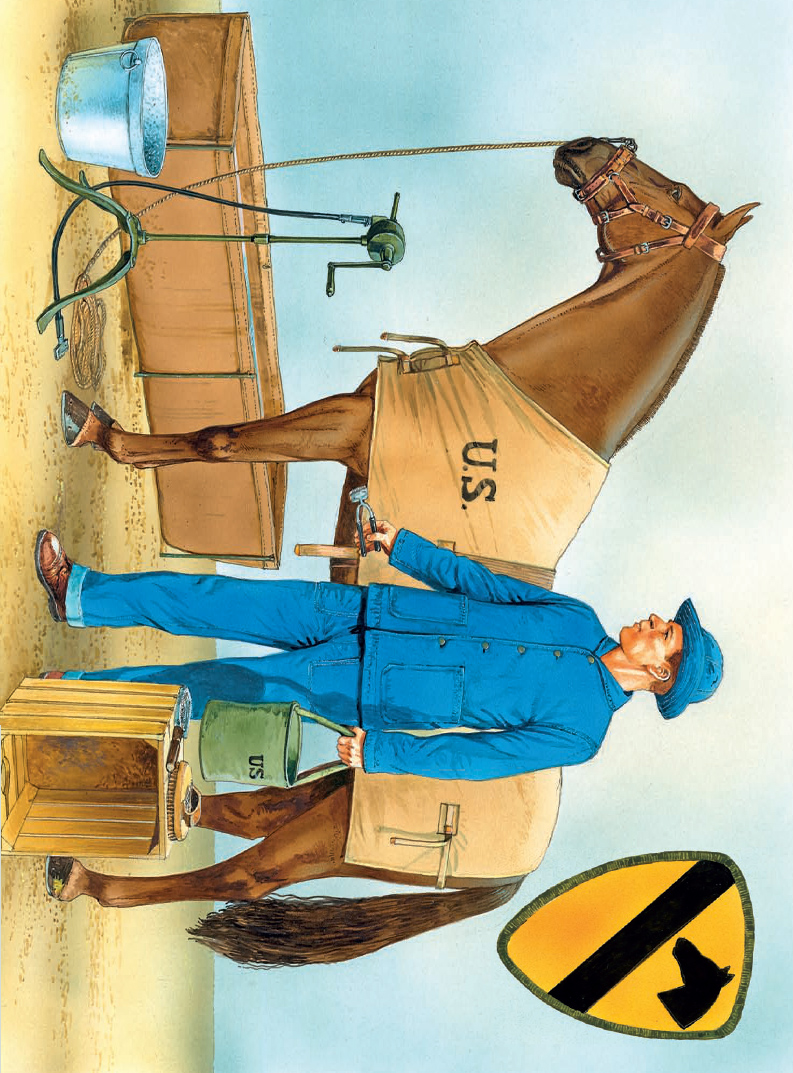

THE CAVALRYMAN AND HIS MOUNT, c.1940 Horses required a great deal of care and much of a cavalryman’s time was dedicated to this end. There was an old cavalry adage, “Take care of your horse first, and if there is nothing else to do, take care of yourself.” After a day’s or even half a day’s mounted training it required one or two hours to care for the mounts – that is, in addition to the routine daily chores of feeding, watering, exercising when not taken out for riding, grooming, and mucking out the stalls. Then there were the related details of general stables cleaning, moving and storing forage and feed, cleaning and maintaining the considerable tack (horse equipment), and occasional horseshoeing and veterinary treatment. Not only were the troopers and their equipment and quarters closely inspected on Saturdays, but the horses, tack, and stables were too, which demanded even more time than the troopers spent on their own upkeep. |

| The trooper wears the pre-war blue denim fatigue uniform and hat. The M1912 horse cover protected mounts in cold weather and prevented them from cooling down too fast. Grooming tools included the handheld horse clipper, M1912 horse brush, and curry comb, the latter used to clean off caked dust or mud. Other gear used in the field included the M1941 galvanized feed tub, canvas 4½-gal bucket, and a stand-mounted, hand-powered horse clipper. The M1918 canvas watering trough was portable; it could be rolled up and then erected with six steel stakes driven in wherever needed. Rather than the usual bridle headstall this horse is fitted with a cavesson used for exercising and training horses. | |

| (Inset)The 1st Cavalry Division patch was among the largest in the Army and was referred to as “the saddle blanket.” |

1st Cavalry Division machine-gun troop gunners practice firing the .30cal Browning M1917A1. These water-cooled guns were retained in the dismounted squadrons’ weapons troops. (1st Cavalry Division Museum)

Five missions were envisioned for horse cavalry regiments: (1) reconnaissance for large formations; (2) offensive maneuver over broken terrain impassable to tanks and trucks; (3) to relieve an infantry regiment in a quiet sector allowing the infantry to engage elsewhere – economy-of-force; (4) as a covering force forward of the main line of resistance, to delay an advancing enemy and confuse him on the location of the MLR; (5) to move rapidly to block a breach in the MLR.

Both the cavalry and infantry became involved in the development of tanks and a doctrine for their employment. The 1st and 13th Cavalry were converted to mechanized units with combat cars (light tanks) and scout cars, the 4th and 6th to mechanized horse regiments with truck-drawn vans to transport horses long distances, and the other 11 remained horse regiments.1 There were 18 National Guard regiments in the 21st through 24th Cavalry Divisions, and 24 in the Reserve’s 61st through 66th Cavalry Divisions; these were skeleton units.

1 Mechanized horse regiments had semi-trailer trucks towing 6-ton combination animal and cargo trailers carrying eight men and eight horses plus their rifles and equipment – a squad.

The National Guard’s four cavalry divisions were inactivated in late 1940 when the Army judged them unnecessary for war plans. Most of the regiments were converted to mechanized cavalry groups or cavalry reconnaissance squadrons in late 1943 and early 1944, and others to artillery units.2 (The six Reserve cavalry divisions constituted in early 1921 were ordered inactivated in January 1942, and all were by April. None had been called to active duty, and their units were converted mainly to artillery. The Office of the Chief of Cavalry was closed in March 1942.)

The 2d Cavalry Division was assigned the 2d, 9th, 10th, and 14th Cavalry, while the 3d and 11th remained non-divisional horse regiments. The 2d Cavalry Division was active from April 1941 to July 1942. The 1st and 13th Cavalry were converted to armored regiments in 1940 and assigned to armored divisions, as were the 2d, 3d, 11th, and 14th Cavalry in 1942. In February 1943 the 2d Cavalry Division was reactivated with the 9th, 10th, 27th, and 28th Cavalry, all Colored units; sent to North Africa in early 1944, it was inactivated there in May, its personnel being reorganized into engineer and service units.

The only remaining horse cavalry units were the 112th and 124th Cavalry of the Texas National Guard, assigned to the 56th Cavalry Brigade. The 112th would depart for the South Pacific in July 1942, and the 124th for India in July 1944.

In Europe a cavalry regiment was generally a battalion-sized unit typically with four to six company-sized “squadrons” made up of platoon-sized “troops.” In US service the regiment, commanded by a full colonel, was of the same echelon as an infantry regiment, but the numbers of sub-units actually assigned or authorized to be manned varied over the years. Full-strength regiments were typically authorized ten or 12 companies; the term “troop” was occasionally used to identify companies, but “company” was the more common designation for these units of between 40 and 100 men commanded by captains. After the Civil War the regiment was standardized with 12 companies, although peacetime regiments might have as few as four. “Battalions” and “squadrons” were not standing units but temporary groupings of companies. Some regiments during the Civil War formed squadrons of two companies, commanded by the more senior company commander, and two to three battalions each of two squadrons, commanded by a major. Others used the terms battalion and squadron interchangeably for a grouping of between two and four companies.

Wearing winter garb, a cavalryman operates a .30cal Browning M1919A2 cavalry light machine gun, a slightly more compact version of the infantry’s M1919A4, identifiable by its slotted barrel jacket. The A4 would replace the A2, but the latter continued to serve alongside it in 1st Cavalry Division units. (1st Cavalry Division Museum)

From 1873 only the term “troop” was used in documents, but “company” remained in common use; even after 1883, when “troop” was the term specifically directed, “company” remained in use until around the turn of the century. Some regiments even mixed both terms. Eventually “troop” and “squadron” were the only terms used for the company- and battalion-equivalent cavalry units.