INTRODUCTION

UNIFORMS: HEADGEAR

FIELD EQUIPMENT

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

THE PLATES

AS JAPAN ENTERED THE 20th century she had visibly awakened from her long feudal sleep, and had begun to modernize with astonishing speed and vigor. The island nation lacked many natural resources, especially the oil that was needed to power factories and machinery. To gain what she needed for industrial and economic growth, Japan made armed forays into the continent of Asia. In the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, Japan defeated ramshackle Chinese armies and made large gains in Korea, as well as acquiring a strategic enclave around the harbor of Port Arthur in Manchuria; but Russia also had ambitions for Manchuria. After successfully expelling Japanese forces by diplomatic means, Russia soon sent her own troops into this territory.

At the turn of the century China was the main Asian arena of international rivalry – vast, potentially rich, but hobbled by an archaic system of government, and only feebly protected by armies whose modernization lagged far behind those of the predatory foreign powers. Japan was competing for influence in China against Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Russia and the United States. These countries all had modern navies as instruments of “gun-barrel diplomacy” to further their economic and territorial interests. Japan’s own pressing need for a modern navy was clear – both to transport men and equipment, and to project Japanese power overseas in sufficient strength to meet any foreign challenge. She had already set about building and training such a navy, drawing upon the most up-to-date foreign examples, and was making extraordinary progress.

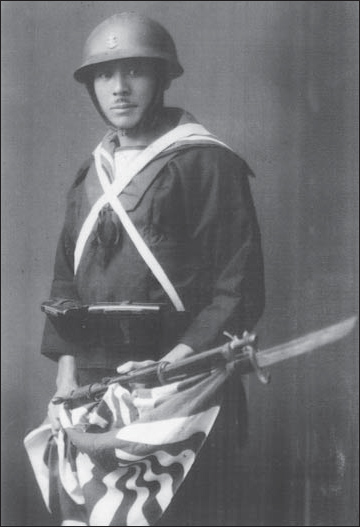

This sailor in Shanghai, China, in 1932 poses in full battle gear with his Type 30 bayonet fixed to his Type 38 rifle, and leather Type 38 ammunition pouches. Attached to his rifle is the Imperial Japanese Navy “rising sun” flag. His steel helmet is the first pattern or “cherry blossom” style, with a frontal brass anchor badge. (Eric Doody)

Tensions in China mounted, and in the spring of 1900 the long-festering resentment against the arrogance of “foreign devils” burst out in an episode known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion.1 The catalyst for this violent spasm, which sought to expel all foreigners and wipe out their influence in China, was a secret society dating back to the 18th century and known as the Fist of Righteous Harmony – thus, “Boxers,” from their skill in martial arts. Members of the society, and more or less open sympathizers, were to be found in the Imperial court surrounding the Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi. With their support, the outbreak lasted from June to October 1900; its most famous episode was the siege of the foreign legations in Beijing, and the march of a multinational force to relieve them. Two full divisions of Japanese troops took part in the operations which crushed the Boxers – the largest of all the eight national contingents.

The Japanese calendar

Between 1868 and the death of Hirohito in 1989, the Japanese have had three imperial reigns. These are referred to by the following throne names: Meiji era (1868–1912), Taisho era (1912–26) and Showa era (1926–89). For the purposes of this text and the dating of Japanese equipment, only the Showa (“Enlightened Peace”) era is relevant. The Japanese monthly calendar begins in January (“1”, the first month), and ends in December (“12”). The Japanese annual calendar begins in the year of enthronement of a new emperor. The Showa era opened when Hirohito ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne in 1926; to identify the Showa year, simply add its year number to 1925:

| Showa year | Showa year | Showa year |

| 7 = 1932 | 11 = 1936 | 16 = 1941 |

| 8 = 1933 | 17 = 1942 | 12 = 1937 |

| 9 = 1934 | 13 = 1938 | 18 = 1943 |

| 10 = 1935 | 14 = 1939 | 19 = 1944 |

| 15 = 1940 | 20 = 1945 |

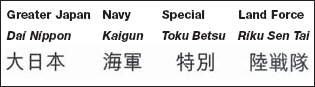

BELOW The kanji characters for the title of the SNLF, as displayed on the ribbon tally of the prewar flat-topped sailor’s cap.

Japanese numbers

When the fighting ended some 100,000 Russian troops were in occupation of Manchuria. Russia promised the international community that she would withdraw these forces by 1903, but failed to do so; instead she pressed ahead with developing military bases and a rail network, hoping to hold on to this new possession. After carefully isolating Russia diplomatically, on February 8, 1904, Japan launched a surprise naval attack against the Russians in Port Arthur, and two days later declared war.2 This Russo-Japanese War was the first clash of two modern armies and navies in the 20th century. Although a decisive land victory was won by Gen Oyama at Mukden in February–March 1905, the final and crushing blow was struck at sea on May 27 by Adm Heihachiro Togo, who led the Japanese in the humiliating defeat of the Russian fleet at the battle of Tsushima. One of the lessons was that all future wars waged by Japan would have to depend upon naval superiority.

During the war against Russia, the Japanese utilized on their warships for the first time small detachments of naval personnel who could be deployed with small arms for shore patrol duties and/or combat. These naval troops could be transported quickly by ships to various trouble spots as the spearhead of any large scale military action. This was the beginning of the Special Naval Landing Force (SLNF) or Tokubetsu Rikusentai.

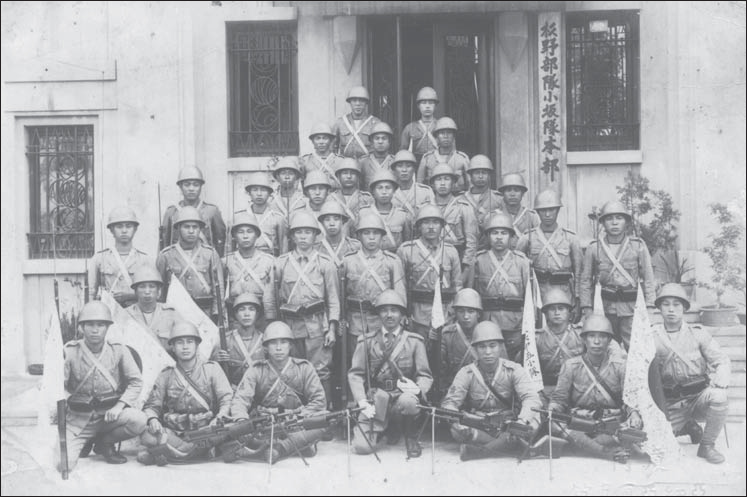

SNLF troops in Shanghai 1934 – the sign to the right of the entrance reads Kaigan Toku Betsu Sen Tai Ozaki (“Navy Special Landing Force, Ozaki Unit”.) Dressed in blue winter shipboard uniform, they wear the Navy Type 2 steel helmet. (Gary Nila)

After the 1905 victory, Adm Togo went to England to study British naval power, while generals from the Imperial Japanese Army traveled to Germany to explore the latest doctrines of ground warfare. Japan continued to pursue this learning curve in small tactical engagements in Korea, China and the South Seas during and after World War I, from which she profited by gaining strategically useful territories in return for a modest investment of military effort. By the eve of the 1930s, the small naval detachments of armed sailors became full time naval infantry units posted aboard various ships.

At this time, China was once again in turmoil due to years of civil war and anarchy; and once again, Japan was preparing to move against Manchuria, where she had already planted both civilian settlers and military garrisons of her Kwantung Army.

In January 1932, Japan made her move in Manchuria, declaring it to be a new and ostensibly independent state, but in fact a Japanese puppet ruled by the Kwantung Army. Far to the south, on January 28 a force of 2,000 Special Naval Landing Force troops saw their first action in what the Japanese refer to as the “Shanghai Incident.” The skirmish was provoked by the Japanese Navy outside the International Settlement, with the goal of capturing Shanghai, while the Chinese protested against Japanese aggression and boycotted Japanese goods. The Japanese Army joined in the fight, but the Chinese prevented the Japanese troops from capturing Shanghai. A temporary truce was signed after foreign intervention.

From their baptism of fire, the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces began to take shape as an elite organization whose units were tasked to handle difficult assignments. The four major naval bases in Japan – at Kure, Maizuru, Sasebo, and Yokosuka – each raised SNLF units which underwent specialized training, included the use of light artillery and amphibious landing operations.

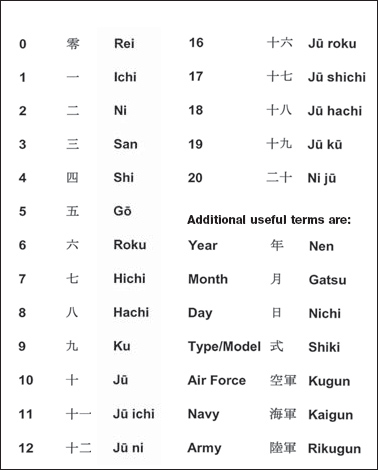

Aboard the IJN destroyer Hiyodori in June 1937, these SNLF troops of the 2nd Shanghai unit pose with their officers. They wear the first pattern green tropical uniforms over white sailor undershirts, and the second, more flared pattern of steel helmet introduced in c.1932 (see photo, page 14). Under magnification, red-on-green round rating patches can be seen on the right sleeve. The four men in the center of the front row hold Bergmann 7.63mm sub-machine guns imported from Belgium or Switzerland; the IJN designated this as the Type “BE” (the first two letters of Bergmann). Some of the others have the long Arisaka Type 38 rifle. (Kazuhiko Osuo)

It was inevitable that continuing Japanese pressure on their territory would eventually force the Chinese to take a stand. The Japanese Army provoked an armed clash with Chinese Nationalist government troops at the Marco Polo Bridge south of Beijing on July 7, 1937; and this ignited the Sino-Japanese War.3 The first large scale engagement by the SNLF in the China War occurred at Shanghai on August 13, 1937. The Chinese 87th and 88th Divisions tried to drive the Japanese from the International Settlement, which was defended by 2,000 SNLF troops, augmented by 300 sailors from their warships on the Yangtze river, and 1,000 Navy men who had just arrived from Japan two days before. Although outnumbered by more than seven to one, the Japanese stood their ground. They rushed in reinforcements from Japan while a political resolution was sought; stubbornness on both sides prevented an end to the fighting, and the war soon raged out of control. The Japanese would eventually raise SNLF units in China (the Hankow, Shanghai, and Yangtze River SNLF).

At the time of Japanese and US entry into World War II on December 7, 1941, there were 16 units of the SNLF in existence. The largest unit, with 1,600 men, was the 1st Sasebo SNLF, followed by the 2nd Sasebo (1,400), and the 1st and 2nd Kure units (1,400 men each). The other 12 units had approximately 750 to 1,000 men each. Within the SNLF there were two specially trained and equipped parachute units, the 1st and 3rd Yokosuka SNLF, with about 750 men in each.4

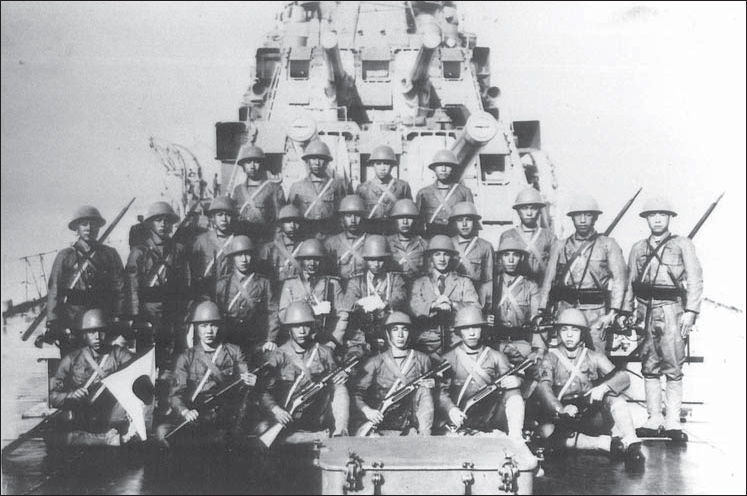

Men of the 1st Maizuru SNLF pose in front of their headquarters in China, 1937. The banner at upper right reads “Sugino Unit – Kosaka Squad Headquarters”; and on the flag above the left shoulder of the third man from the right, front row, the word shotai