NEW VANGUARD • 143

The birth of the steel navy

| LAWRENCE BURR | ILLUSTRATED BY IAN PALMER & JOHN WHITE |

INTRODUCTION

A NAVAL RENAISSANCE

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION

THE SHIPS

• Ships authorized in 1883

• Ships authorized in 1885

• Ships authorized in 1886

• Ships authorized in 1887

• Ships authorized in 1888

• Ships authorized from 1890 to 1891

• Ships authorized in 1892

• Ships authorized from 1893 to 1898

• Ships authorized in 1899

• Ships authorized in 1900

• Ships authorized from 1902 to 1904

CRUISERS IN ACTION

• The Spanish-American War, 1898

• The battle of Manila Bay

• The battle of Santiago

• Naval diplomacy

POINTING THE GUNS

• The men behind the guns

USS OLYMPIA

CONCLUSION

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

APPENDIX

The modern US Navy, with nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and submarines and Aegis cruisers with high-technology combat and communication systems stands in stark contrast to the US Navy as it existed at the beginning of 1883. At that time, the US Navy comprised antiquated wooden hulks and was outclassed by 12 other nations. The authorization of the all-steel cruisers, Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago, on March 3, 1883, marked not only a change in material for warship construction but also the beginning of a change in US naval strategy, and the first stirrings of an expansionary foreign policy.

From 1883 to 1904, 39 cruisers were authorized, providing the crucial impetus to the US steel and shipbuilding industries to invest in the new technologies necessary to build a modern steel navy. US cruisers figured prominently in the two naval victories of the 1898 Spanish-American War, with America acquiring a string of new territorial possessions in the Caribbean and Pacific. Thus, the design and development of these cruisers marked the emergence of the US as a global naval power.

At the conclusion of the American Civil War in April 1865, the US Navy was one of the largest navies in the world, with a fleet in excess of 600 ships. More importantly, it was the most technologically advanced navy. Over the preceding years, the US Navy had been the first to introduce steam engines and the screw propeller and the first to eliminate sails on a steamship. The commissioning of the USS Monitor in February 1862 introduced armored revolving gun turrets on a ship’s centerline, revolutionizing warship design. USS Wampanoag was the fastest steamship in the world in 1868.

However, during the post-1865 period, the US Navy gave up its technological leadership. In 1870, Navy regulations forbade the use of steam power. In 1874 it stopped ordering new warships. By 1881, the Navy comprised 26 operational ships, only four of which had iron hulls.

The coming of peace in 1865 allowed the United States to refocus its national efforts on Manifest Destiny, the settling of the West, and to develop the US’s agricultural, mineral, and industrial resources. Waves of immigrants helped fuel the rapid expansion of the US economy. In 1874, US exports exceeded imports by value for the first time, reflecting the global emergence of US manufacturing capability. Reconstruction of the South was finished. By 1880, government debts incurred for the Civil War had been significantly reduced, and the federal government enjoyed a solid budget surplus.

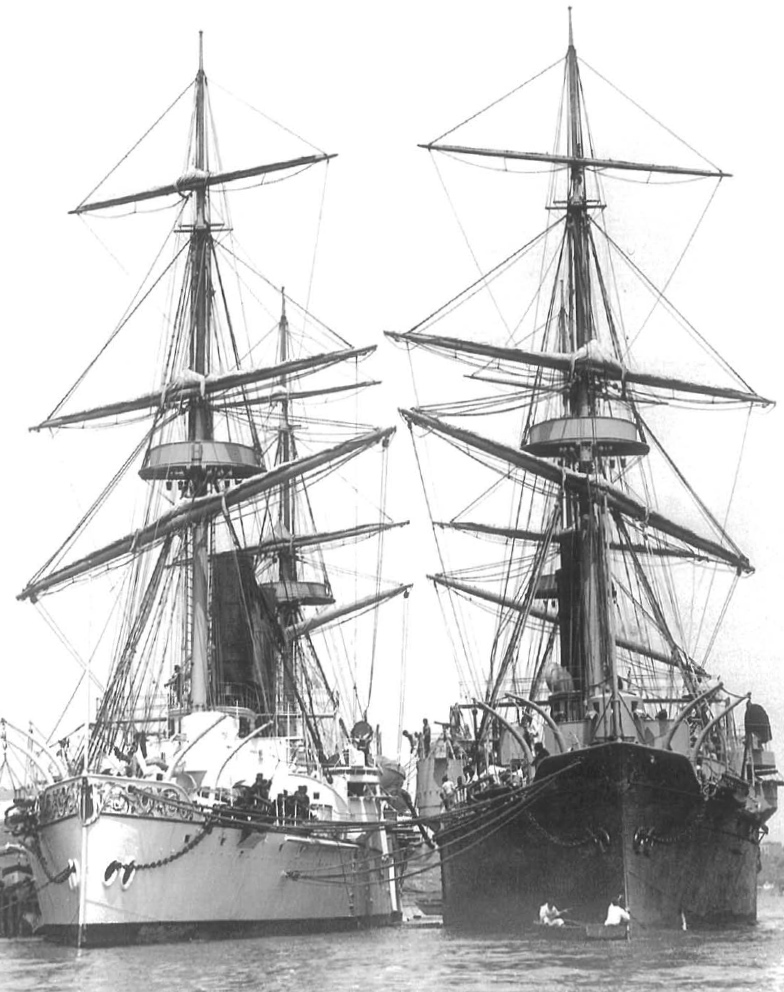

USS Atlanta and Boston, showing their combination of sail power and steam power. This mix was necessary to give the ships the cruising range in a time of low-powered steam engines and the absence of overseas coaling stations.

This growing economic strength sparked a national debate on the need for both an army and a navy. European imperialism was seeking new markets and territories in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Recognition that countries with significantly smaller economies were acquiring powerful, modern warships that could readily defeat any ship the US Navy possessed forced the administration of President Chester Arthur to act. In November 1881, Secretary of the Navy William Hunt advised both the President and the US Congress that, “The condition of the navy imperatively demands the prompt and earnest attention of Congress – or – it must soon dwindle into insignificance.”

A key element in the national debate was provided by Theodore Roosevelt’s book The Naval War of 1812, published in early 1882. Roosevelt identified that the United States won the War of 1812 because its navy was efficient and technically advanced. Roosevelt stated, “It is folly for the Republic to rely for defense upon a navy composed partly of antiquated hulks, and partly on new vessels rather more worthless than the old.”

After significant political and public debate, as well as detailed reports submitted by two Naval Advisory Boards, new Secretary of the Navy William Chandler finally obtained Congressional approval for the construction of four new ships, all to be built from steel. Three ships, the USS Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago, were to be cruisers. The remaining ship, the USS Dolphin, was to be a dispatch vessel. These ships were referred to as the “ABCD ships,” and they marked the birth of the new steel navy. The decision to build what were, in naval terms, three modest cruisers, had dramatic implications for the Navy, the shipbuilding industry, and, ultimately, America’s role in world affairs.

In addition to obtaining Congress’s approval for the new steel ships, Secretary Chandler attacked the waste, inefficiency, and processes of the “old navy.” Naval shipyards, fully manned but idle, were rationalized. Maintenance and repair programs on obsolete ships were stopped, forcing these ships to be scrapped. Reform of naval personnel policy commenced with 400 officers being retired.

With the decks cleared, Chandler turned to the future of the “new navy,” and in 1884, established the Naval War College (NWC), the first postgraduate naval education establishment in the world. The NWC’s function was to teach the principles of war to naval officers so that “with their deeper understanding of the tactics and strategy of war” they would be both captains of ships and captains of war, to paraphrase Winston Churchill’s comment on the Royal Navy in 1914.

|

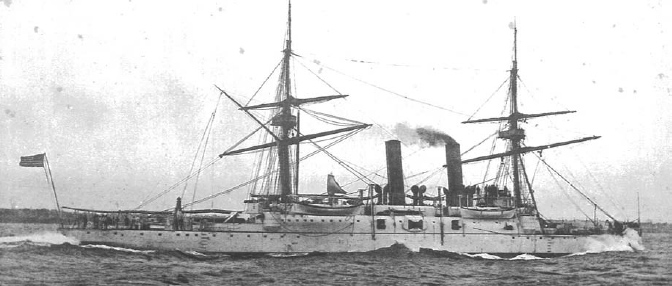

EARLY CLASSES OF CRUISER USS Atlanta Although Atlanta and Boston were obsolete when commissioned, they provided valuable experience for the new navy. Boston fought at Manila Bay with Dewey and served until 1946. USS Chicago The Chicago suffered from the same design issues as the smaller Atlanta and Boston, but at 4,500 tons, she was over four times larger than the last iron ship built for the Navy. Chicago introduced twin screws, but her compound overhead beam engines protruding through her decks belied her otherwise modern innovations. For armor protection, she relied on a steel deck supported by coal bunkers. Chicago was heavily armed and much admired by other navies, and served until 1936. |

USS Boston on her speed trials at Newport, Rhode Island. Authorized in 1883, problems with steel quality and new construction methods delayed her commissioning until May 1887. Boston participated in the battle of Manila Bay.

The establishment of the NWC followed the establishment of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) in 1882. The ONI’s function was to collect and evaluate military and naval information from abroad, through its overseas naval attachés, and to undertake strategic planning for the Navy. With ONI and the NWC, the new navy had the intellectual and informational resources and the time to study, consider, and plan for the future.

The NWC played a major contributing role to the debate on the importance of seapower with the 1890 publication of Alfred Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783, which established a battle fleet as a prerequisite for gaining command of the sea. Mahan had been appointed to the NWC in 1885, and his book was based upon a series of lectures he had given at the NWC.

American naval strategy in 1883 was based on coastal defense and commerce raiding. The ABC cruisers were approved within this context, with the additional element of “showing the flag,” particularly in the Pacific, to support growing US commercial interests. The debate questioned the viability of a coastal defense and commerce-raiding strategy when the range of new naval guns outranged the guns on unseaworthy coastal defense monitors. Additionally, an effective commerce-raiding strategy would require a large number of cruisers scouring the seas to interdict enemy merchant shipping. This in turn raised the issue of the need for a fleet that could defend the US coast by defeating at sea an attacking naval force. This debate took many years to mature, and during this period, the new navy had to come to grips with more practical issues.

The development of the new navy was determined by the development of the design and construction capabilities of American shipbuilders and the production capabilities of American steelmakers. The decay of the US Navy from 1866 to 1883 had resulted in a decline in the American naval shipbuilding industry to the point that no US Navy yard was capable of building steel ships.

Only two private shipyards, John Roach & Sons of Chester, Pennsylvania, and William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, bid on the contracts to build the three cruisers and the dispatch vessel. Roach won the contract to build all four ships. Technical problems in fabricating steel plates and casting large steel forgings for the propeller shafts, plus constant changes to design plans and specifications, slowed construction. Political interference resulted in the contracts with Roach being invalidated by the US government, forcing Roach into bankruptcy. As US Navy yards could not complete the ships, the US Navy assumed control of Roach’s shipyards until the ships were completed.