| DAVID FLETCHER | ILLUSTRATED BY HENRY MORSHEAD |

• Naval operations

• The Machine Gun Corps (Motors)

• Gallipoli

• ‘They searched the whole world for war’

• The Yeomanry

• India

• An interim design

• The 1920 Pattern cars

• The Royal Air Force

• Ireland

• India

• The 1924 Pattern cars

• Four wheels good – six wheels better

• The Home Guard

Rolls-Royce: the hyphenated name has become a byword for top quality; you can buy the Rolls-Royce of lawnmowers, of food processors, whatever you like. One never seems to hear Mercedes-Benz used in the same way. It was ever thus; as early as 1906 members of the War Office Mechanical Transport Committee, attending the Motor Car Show at Olympia in London, were seduced by the quality of a 15hp Rolls-Royce, although they had sense enough to realize that at £525 it was far too expensive for the military budget. It takes a war to justify that.

The first Rolls-Royce armoured car was privately owned. It belonged to a member of the Eastchurch Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service, which in August 1914 was based in Dunkirk. Its commanding officer, Commander Charles Rumney Samson R. N. was something of a firebrand who supplemented his squadron’s flying activities by ground-based reconnaissance forays using his pilots’ private cars, and these turned into active fighting raids against German patrols operating in the area. As a result of this, and in particular an action at Cassel on 4 September 1914, it was decided to fit armour on to three of these cars, although armour was a relative term. Charles Samson’s brother Felix was the prime mover in this project; however, it was up to Charles Samson himself to obtain authority from the Admiralty Air Department in London. The cars selected were Felix Samson’s Mercedes, a 50hp Rolls-Royce – which may well have been Charles Samson’s own car – and a Wolseley. Work on the cars was undertaken by the Dunkirk shipbuilders Forges et Chantiers de France. Samson admits that the ‘armour’ was 6mm boiler plate, which was only proof against a rifle bullet above 500 yards. Although Charles Samson states that the protective plate was designed by his brother Felix, the pattern is very similar to that seen on some early Belgian armoured cars with a high, V-shaped shield at the back, and a plate covering the radiator and another around the dashboard. It was armed with a borrowed French Lewis gun to begin with and then a water-cooled Maxim, mounted on a tripod and capable of firing over the rear shield. The Belgians had adopted the practice of reversing towards the enemy, ready for a swift getaway should the need arise. This may well have been the idea behind the British design as well.

The Royal Naval Air Service, as a branch of the Royal Navy, came under the watchful eye of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, although Samson’s direct superior, as Director of the Admiralty Air Department, was Commodore Murray Sueter. So while Samson experimented with a variety of locally built armoured vehicles in Flanders he was urging Sueter, in London, to expand the fleet and inevitably Winston Churchill was interfering. The final number of armoured cars authorised was 60, of which 18 would be Rolls-Royce and 21 each on Wolseley and Clement-Talbot chassis. The design, for some reason, was worked out by the Admiralty Air Department and Lord Wimborne in Britain with no reference to Samson as far as anyone can tell, but the design was submitted to Churchill, who approved it, and a wooden mock-up was created on a real Rolls-Royce chassis to Lord Wimborne’s design.

The design did not prove popular with Samson’s men because it offered no protection to anyone whose torso projected above the waist-high armour. The only member of the crew to have a seat appears to have been the driver, who was also sheltered to some extent by a steel hood. For the rest of the crew, however, it was necessary to lie down if they found themselves under fire. The sketch submitted to Churchill showed a car with four potential machine-gun mountings around the body although in practice only two appear to have been provided, with the most popular the one on top of the driver’s hood. In any case, there was only one Maxim to spare for each car. The armour, such as it was, is described as 4mm nickel chrome steel, lined on the inside with oak planks. There are differences in detail between the various cars. Most had some sort of protection for the tyres, while the radiator was covered by an angled plate, although hinged radiator doors are also seen. Eight cars, probably Talbots and Wolseleys, were built by the Royal Naval Dockyard at Sheerness but subsequently the armour was fitted by each manufacturer at their works, which might account for the differences. The cars were organized into four squadrons, each of 15 cars and with crews largely drawn from the Royal Marines. The first of these, No. 1 Squadron commanded by Lieutenant Felix Samson, was supposed to be equipped entirely with Rolls-Royces. Samson remarks that ‘the Rolls-Royces proved by far the most reliable and suitable’. However, it would be wrong to take the orderly arrangement this implies at face value. Flight Commander T.G. Hetherington, who was ordered to join Felix Samson’s squadron with four Wolseleys, was horrified by what he found in France. Under Charles Samson anarchy reigned, nobody seemed to know what was going on and organization was non-existent. Evidence suggests that none of the squadrons was ever completed, let alone with the makes of car laid down on paper. Yet it was the British penchant for improvisation at its best, where courage and daring made up for a lack of order and it adds a bright page to an otherwise drab account of a long and depressing war.

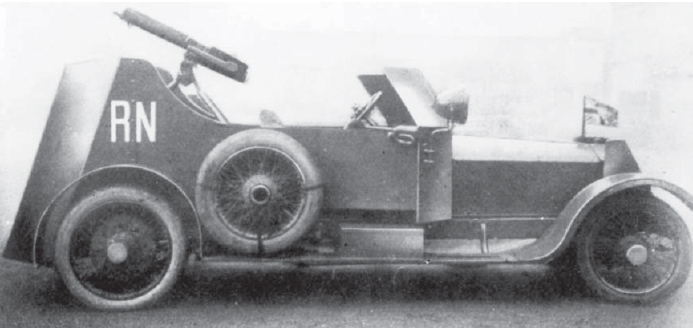

The first three of Commander Samson’s armoured cars must have looked like this, although this is the Rolls-Royce showing the additional panels of steel covering the radiator, the driver’s position and the machine-gun post at the back. It is also the only one of these three cars that appears to have been photographed.

Samson had one of the original Admiralty Pattern Rolls-Royce cars rebuilt, adding higher sides to protect the crew. It was sometimes seen towing a 47mm gun. Nothing is known about the ultimate fate of the car although Samson later found the gun in Gallipoli and reclaimed it.

Most of the cars underwent modifications in service. Some had planks, carried in brackets on the sides, which could be used to bridge ditches and narrow trenches, while one Rolls-Royce – probably on Samson’s orders – had a raised body fitted and was sometimes seen towing a 47mm gun on an improvised two-wheeled carriage. In addition to the 15 Rolls-Royces of No. 1 Squadron, two more are listed as being attached to No. 2 Squadron, which, on paper at least, had 12 Wolseleys. It was the only 14-car squadron of the four, always assuming that any of the squadrons ever reached full strength. But events were moving rapidly, both in terms of technology and on the battlefield.

Writing in Volume 1 of The World Crisis Winston Churchill said: ‘Thus at the moment when the new armoured-car force was coming into effective existence at much expense and on a considerable scale, it was confronted with an obstacle and a military situation which rendered its employment practically impossible.’

All four squadrons were operational by October 1914 but whether that implies complete to establishment is unclear, and in any case opportunities for action were diminishing rapidly with the creeping expansion of trench warfare. The Admiralty in London was looking at a new design: a turreted car that offered much more protection for the crew. Flight Lieutenant Arthur Nickerson is the man credited with the design of the turret, although the turret itself was by no means a new idea. Turreted armoured cars had existed since about 1904 though they were mostly prototypes, but the idea of the turret goes back further still, to warships and armoured trains. Nickerson, however, created a turret that offered all-round protection with a minimum of weight; unfortunately its curved sides and thin armour with curved plates were not proving easy to produce. Lieutenant Kenneth Symes was working on it but the best results were achieved by Beardmores in Glasgow. The turret armour was 8mm thick, which made it immune to armour-piercing rounds then employed by the Germans.

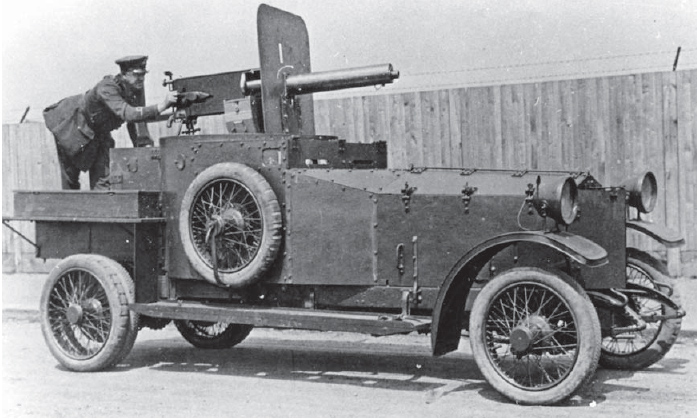

In addition to the regular turreted cars the RNAS staff at Barlby Road, which lies behind the wooden fence, adapted this Rolls-Royce to carry the heavier 40mm Vickers Pom-Pom although this presented the gunner with a problem.

Even so there was no obvious uniformity. Examination of surviving photographs shows dozens of minor variations in the pattern of the armour and if that were not enough the chassis available differed depending upon the year they were built. This may well have been true of all manufacturers but in the case of Rolls-Royce it has been tabulated in great detail and reveals year-on-year changes with continual minor improvements, so each chassis number needs to be evaluated in this light. For example, chassis produced before 1911 had an exposed drive shaft whereas cars in the 1700 series, produced from 1911 onwards, had the shaft enclosed in a torque tube; chassis produced before 1913 had a three-speed gearbox and from the 1100 series onwards a four-speed box was standard. Unless one knows the chassis number of a particular car this is very difficult to ascertain. As a result it is entirely possible, although by no means certain, that some of the 18 cars earmarked as the first model were completed as the second type, with turrets.

During this time the headquarters of what became the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division (RNACD) had moved from its formative site at the Sheerness naval dockyard on the Isle of Sheppey to the Daily Mail