The frozen fortress

| ROBERT FORCZYK | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

Series editor Marcus Cowper

German  Soviet

Soviet

German  Soviet

Soviet  Order of battle

Order of battle

German  Soviet

Soviet

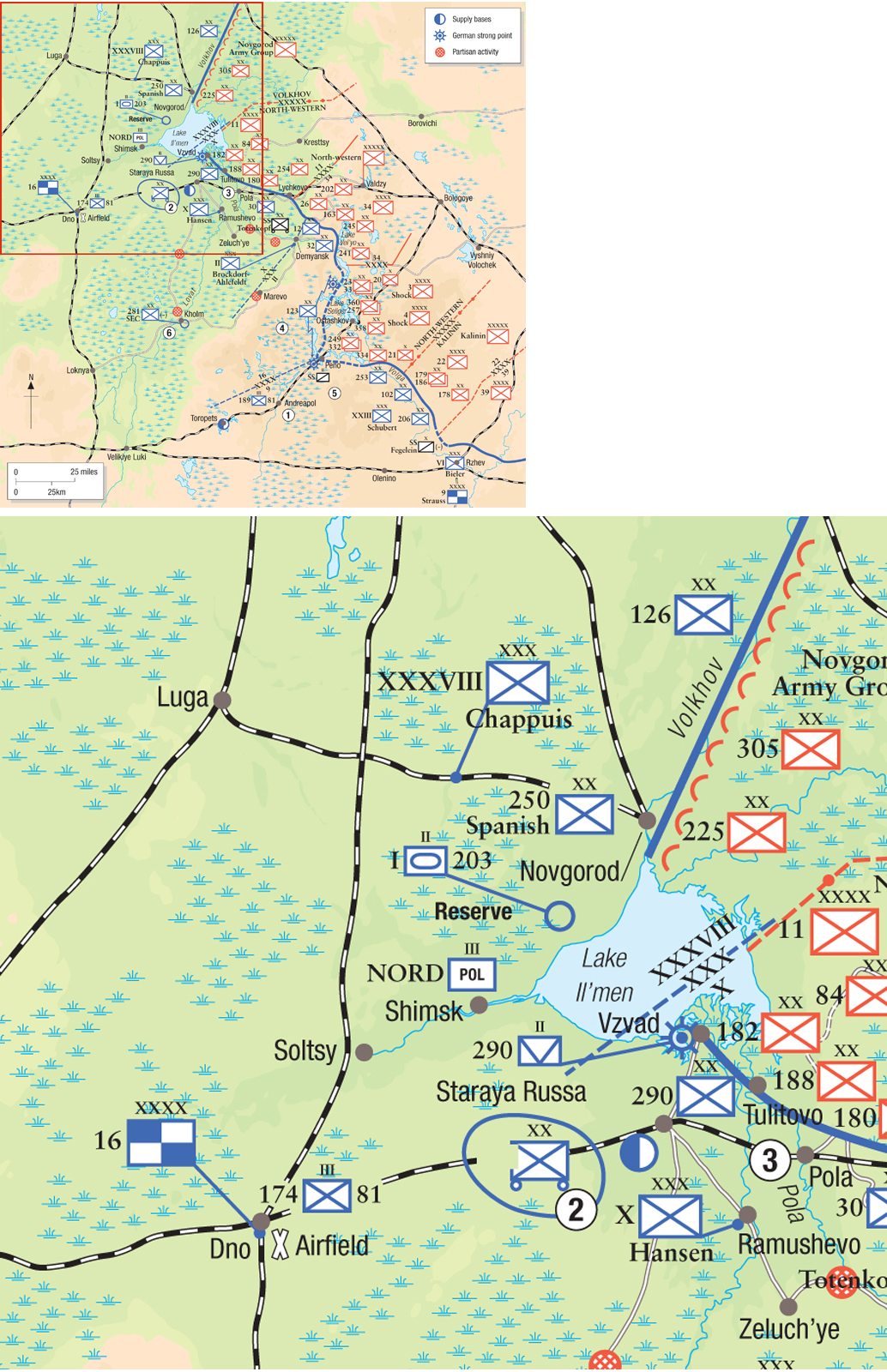

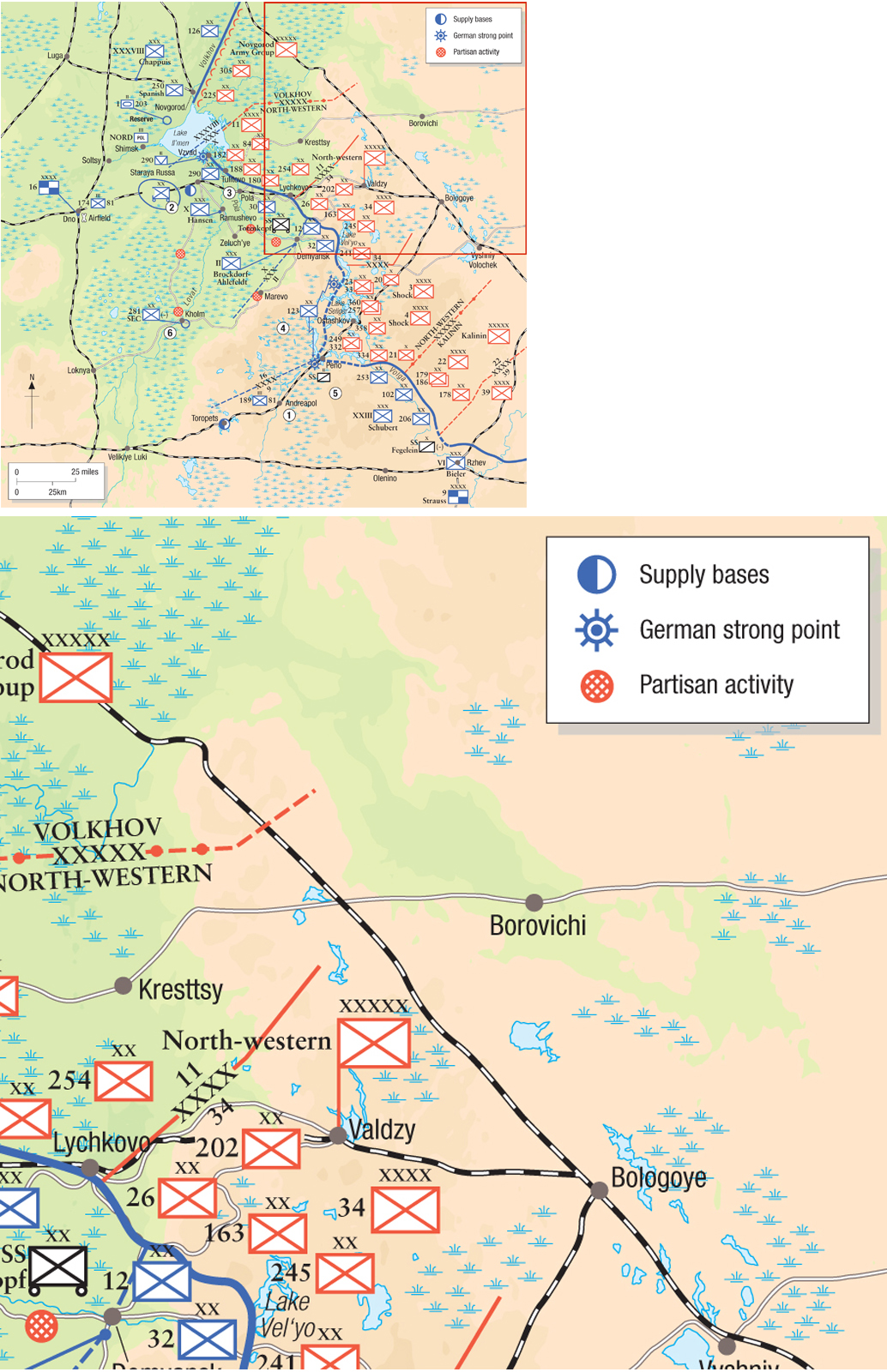

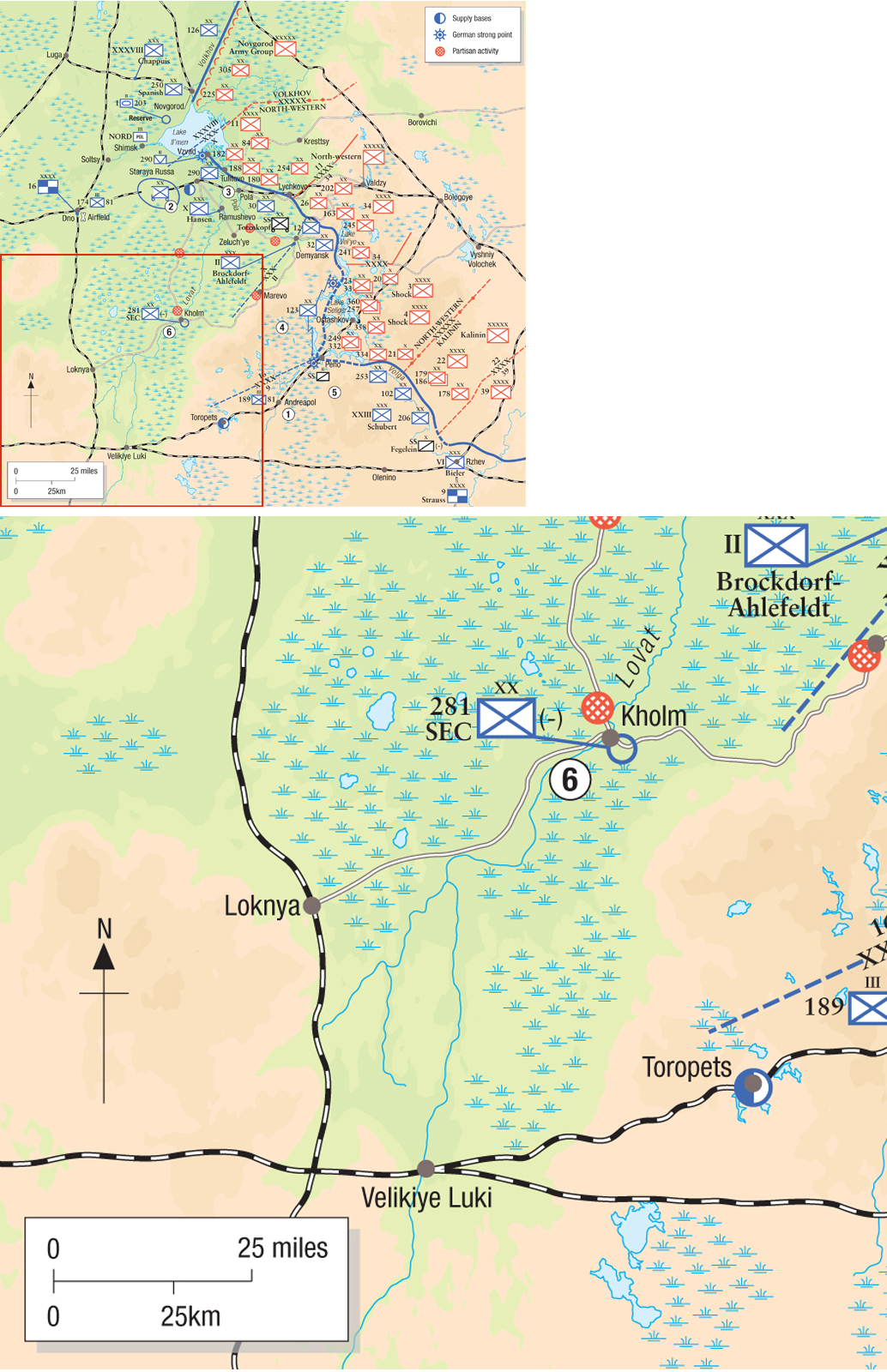

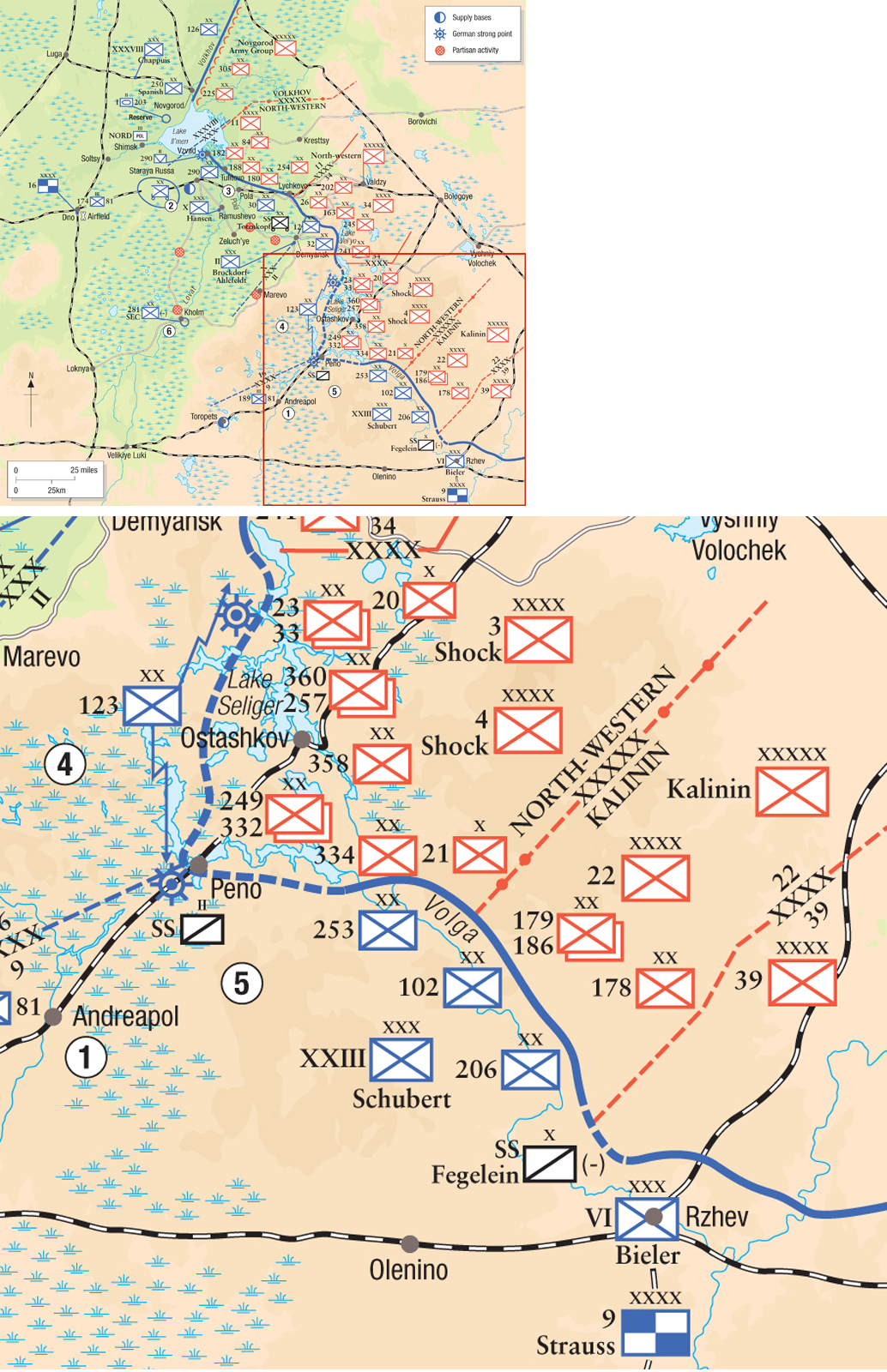

The Soviet Winter Counteroffensive, January 1942  Closing the Demyansk pocket, February 1942

Closing the Demyansk pocket, February 1942

The airlift, February–May 1942  The siege of Kholm, January–May 1942

The siege of Kholm, January–May 1942

The German relief operations, March–May 1942  The battle of the Ramushevo corridor, May–October 1942

The battle of the Ramushevo corridor, May–October 1942  The end game, November 1942 to February 1943

The end game, November 1942 to February 1943

| 1 | 189. Infanterie-Regiment (81 ID) arrives by train from France at Andreapol on 5 January. |

| 2 | 18. Infanterie-Division (mot.) redeploying from Tikhvin to serve as AOK 16 reserve force. |

| 3 | 290. Infanterie-Division is defending a nearly 30-mile-wide (50km) sector along the Pola River with only company-sized strongpoints. |

| 4 | 123. Infanterie-Division screens the right flank of AOK 16 across a 35-mile-wide (55km) sector. |

| 5 | The reconnaissance battalion from SS-Kavallerie-Brigade screens the left flank of Heeresgruppe Mitte near Peno. |

| 6 | 281. Sicherungs-Division has various units operating against Russian partisans around Kholm. |

Although the original plan for Operation Barbarossa developed in late 1940 had specified Leningrad and Moscow as critical objectives, it had provided no real guidance about the heavily forested and lake-strewn region that lay between the two cities. Aside from the ancient Russian capital of Novgorod, there was little of strategic value in the area around the Valdai Hills except the main Moscow–Leningrad railway line. Both Hitler and the German Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) simply assumed that intermediary areas such as these would easily fall into the Wehrmacht’s hands once the Red Army was crushed in the opening stages of Barbarossa. Nor did the OKH anticipate positional warfare in the vast and remote areas of northern Russia, but instead believed that rapid manoeuvre warfare would compensate for lack of sufficient forces to create a continuous front.

German infantry advance into a village south of Lake Il’men in August 1941. Initially, AOK 16 planned on only transiting through this region en route to the Valdai Hills but was forced onto the defensive by a series of Soviet counterattacks around Staraya Russa that encircled part of X Armeekorps (AK) for a week. (Ian Barter)

By October 1941, the German troops in AOK 16 were settled into a defensive posture and had plenty of time to build field fortifications. This higher level of preparedness was a major advantage in surviving the Soviet Winter Counteroffensive and holding the Demyansk salient for the rest of 1942. (Ian Barter)

When the German invasion began on 22 June 1941, the Soviet North-western Front had 440,000 troops deployed with its 8th and 11th Armies on the border in Lithuania and with 27th Army in Latvia. Caught totally by surprise, the two Soviet armies on the border suffered 20 per cent losses in personnel in the first 18 days of the invasion and were forced to retreat 375 miles (600km) across the Baltic States. Forced apart by the German Panzer Schwerpunkt, 8th Army withdrew towards Narva, while 11th Army fell back towards Staraya Russa and 27th Army towards Kholm. The bulk of Heeresgruppe Nord under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb advanced towards Leningrad, leaving only 16. Armee (AOK 16) under Generaloberst Ernst Busch to guard the right flank of the army group. By mid-July, X Armeekorps (AK) was pushing towards Staraya Russa while II AK advanced slowly upon the town of Kholm. Both Leeb and the OKH viewed the AOK 16 mission as an economy of force effort, accomplished with the bare minimum of forces and supplies diverted from the main objective of Leningrad.

However, the North-western Front was not annihilated in the first two months of the German invasion – despite horrendous losses, particularly in tanks and artillery – and it soon became apparent that the Wehrmacht had invaded the Soviet Union with grossly insufficient forces for such a mammoth task. While powerful Panzer Schwerpunkte pushed rapidly towards the prizes in Moscow and Leningrad, Heeresgruppe Nord and Heeresgruppe Mitte had only tenuous contact with each other. Once out of harm’s way, the Soviet 11th Army stopped retreating when it reached the area of swamps and forests south of Lake Il’men, knowing that the road-bound Germans could not easily pursue them in this terrain. After catching its breath and receiving reinforcements, the North-western Front began launching a series of painful counterattacks that kept catching AOK 16 by surprise. On 15 July 1941, the Soviet 11th Army counterattacked west of Lake Il’men and was able briefly to encircle and maul 8. Panzer-Division at the battle of Soltsy. As a result, Generalfeldmarschall von Leeb became very concerned about his vulnerable right flank and decided to order AOK 16 to secure a defensible line along the Lovat River. As a result, in early August 1941, X AK seized Staraya Russa while II AK occupied Kholm.

Despite securing these towns, which were vital transportation hubs in a nearly roadless region, Generaloberst Busch did not have sufficient forces to create a continuous front between Staraya Russa and Kholm. It was not long before the North-western Front decided to take advantage of the 30-mile-wide (48km) gap between the two German corps. While 11th Army conducted a fixing attack against X AK at Staraya Russa on 12 August, the newly raised 34th Army pushed into the gap and was able to sever the main German lines of communication. Two German divisions – 30. and 290. Infanterie-Divisionen – were briefly surrounded in Staraya Russa until Leeb sent General der Infanterie Erich von Manstein’s LVI AK (mot.), spearheaded by SS-‘Totenkopf’ Division, to relieve the trapped forces at Staraya Russa. In less than a week, Manstein was able to punch through the thin Soviet encirclement and crush the overextended 34th Army. The North-western Front retreated back across the Lovat River, to regroup.

The battle for Staraya Russa in August 1941 shaped the forthcoming Demyansk–Kholm campaign of 1942, as constant Soviet attacks from the Valdai Hills region enticed AOK 16 to keep pushing ever farther eastward, past the relative safety of the Lovat River line. Stung by this second, nearly successful Soviet counterattack, Leeb resolved to ensure that his right flank was secure before beginning the final push on Leningrad. He ordered Manstein’s corps to remain with AOK 16 and continue pushing eastward across the Lovat River, rather than supporting the drive on Leningrad. Given that the priority for Soviet reinforcements was Moscow and Leningrad, there was little that the weakened North-western Front could do to stop AOK 16 from slowly pushing the mauled 34th Army back towards Demyansk, although 11th Army and 27th Army held firm on the flanks. Manstein’s LVI AK (mot.) was able to advance down a narrow road through the swamps east of the Lovat River and capture the town of Demyansk in early September, but the result was that a handful of German divisions were now overextended and vulnerable to counterattack. Indeed, the idea that an entire army corps with three divisions would place its main supply route on a single 55-mile-long (90km) dirt road from the railhead at Staraya Russa was not only at odds with German manoeuvre doctrine but bordered on the ludicrous.

Soviet KV-1 tanks and infantry attack through flooded marshland near Staraya Russa in the autumn of 1941. The North-western Front continued to conduct small-scale attacks against AOK 16’s positions throughout the rest of 1941, but heavy tanks proved almost useless in this kind of terrain. (Phil Curme)

German troops moving through marshy, forested terrain near Staraya Russa. The Wehrmacht was unaccustomed to operating in the type of terrain prevalent south of Lake Il’men, which favoured light infantry units and partisans, rather than mechanized divisions. (Ian Barter)

In early September, LVI AK (mot.) was withdrawn to reinforce Operation Typhoon against Moscow, but SS-‘Totenkopf’ remained with X AK. Before X AK could establish a strong defence, the North-western Front struck again on 24 September, catching SS-‘Totenkopf’ by surprise at the village of Luzhno, 12 miles (20km) north of Demyansk. The Waffen-SS Division was pounded for three days and suffered over 800 casualties, but held. As October arrived, AOK 16 made one last effort to push east from Demyansk and Staraya Russa, but succeeded only in seizing more barren wilderness that was difficult to defend. Once the first snow arrived, the on-again/off-again AOK 16 offensive came to a halt and Busch ordered all three of his corps to construct winter defences. Busch had XXXVIII AK defending the area north of Lake Il’men, including Novgorod, with X AK holding the area east of Staraya Russa and II AK holding the area between Demyansk and Ostashkov. Over the next two months, a period of stalemate settled over the area between Lake Il’men and Lake Seliger. Since the North-western Front had suffered 178,000 casualties between 10 July and the end of December 1941, it was in no position immediately to take advantage of the German shift to a defensive posture. Enjoying the respite from Soviet counterattacks, AOK 16 dug in and waited for the campaign to be decided elsewhere, at Leningrad and Moscow. Although AOK 16’s lines were thin and the connection with Heeresgruppe Mitte’s left flank was tenuous, the OKH assumed this to be a temporary but acceptable risk.

However when the German advances upon Leningrad and then Moscow were stopped short of their objectives, it became apparent that the risk in AOK 16’s sector would not be temporary. Operation Barbarossa had barely culminated when the Soviet Winter Counteroffensive began, first in front of Moscow and then at Tikhvin, east of Leningrad. Initially, AOK 16 was not affected by these actions and December passed fairly quietly on this front. The 290. Infanterie-Division, holding the most exposed section of the X AK sector, suffered a total of only 127 combat casualties in December. Indeed, this barren wilderness appeared to be just about the only quiet section on the entire Eastern Front, as virtually every other German army was stressed by the Soviet counteroffensives. Nor did AOK 16 suffer as severely from the cold as other German troops in Russia did, since its units had sufficient time to build fieldworks and plenty of timber for bunkers. As the Germans had already discovered, the terrain in this region favoured the defence and Busch was confident that AOK 16 could hold its ground through the winter. The only area of real concern was at the inter-army group boundary on the right flank, near Ostashkov and Lake Seliger. Throughout the 1941 campaign, the connection between Heeresgruppe Nord and Heeresgruppe Mitte had been poor and recurrent Soviet counteroffensives from the Valdai Hills only made it worse. The OKH also recognized that this area was potentially quite dangerous and promised Busch reinforcements. Even though Heeresgruppe Mitte was in full retreat from Moscow and Soviet offensives were appearing across the front, the OKH was transferring a number of units from occupation duty in France and promised Busch 81. Infanterie-Division. When the first elements of this division began arriving by rail at the end of December, Busch sent a Kampfgruppe composed of Infanterie-Regiment 189 and an artillery battalion to reinforce his right flank, but directed the rest of the division to concentrate around Staraya Russa. He also received the badly depleted 18. Infanterie-Division (mot.) from AOK 18 at Leningrad.

From the Soviet perspective, the area south of Lake Il’men initially seemed to offer merely a cost-effective venue for diverting German reserves away from Leningrad and Moscow. Yet as the Soviet Winter Counteroffensive gathered momentum, the Stavka recognized that the poorly guarded boundary between Heeresgruppe Nord and Heeresgruppe Mitte could be exploited to shatter the entire German front in northern Russia. Consequently, in late December the Stavka began funnelling fresh reinforcements and replacements to enable the North-western Front to mount a major attack against AOK 16 in January 1942. Stalin was confident that this forthcoming operation could cripple both German army groups and lead to decisive results.

| 1941 | |

| 6 August | AOK 16 captures Staraya Russa and Kholm. |

| 12 August | Soviet 11th and 34th Armies attack X AK at Staraya Russa and isolate two German divisions. |

| 19 August | Manstein counterattacks with LVI AK (mot.) and rescues X AK. |

| 31 August | Demyansk captured by LVI AK (mot.). |

| 24–27 September | Soviet attacks against SS-‘Totenkopf’ Division at Luzhno are repulsed. |

| 29 September | First German supply train arrives in Staraya Russa. |

| 8–19 October | AOK 16 briefly renews advance eastwards to improve its positions. |

| 18 December | North-western Front receives order from Stavka to begin planning for the Winter Counteroffensive. |

| 1942 | |

| 6–7 January | Winter Counteroffensive by North-western Front against 16 AOK begins. |

| 9 January | 3th and 4th Shock Armies begin attacks across frozen Lake Seliger, striking right flank of AOK 16. |

| 11 January | 11th Army severs the main supply route to Demyansk. |

| 12 January | Leeb requests permission to pull back II and X AK, but Hitler refuses. |

| 15 January | 4th Shock Army breaks through at Andreapol. |

| 17 January | Leeb is relieved and replaced by Küchler. |

| 19 January | The Germans rush LIX AK to Vitebsk to plug hole between Heeresgruppe Nord and Heeresgruppe Mitte. |

| 20 January | 11th Army attacks Staraya Russa while 4th Shock Army overruns supply depot at Toropets. Primary land communications with II AK are severed. |

| 21 January | 3rd Shock Army surrounds Kampfgruppe Scherer at Kholm. |

| 22 January | 3rd and 4th Shock Armies transferred to Kalinin Front. |

| 22–25 January | Heavy fighting at Kholm. |

| 29 January | 1st GRC arrives at front east of Staraya Russa. |

| 3 February | 2nd GRC committed at Staraya Russa. |

| 8 February | 1st GRC captures Ramushevo on the Lovat. |

| 12 February | Luftflotte 1 begins airlift to Demyansk pocket. |

| 8–13 February | 1st Shock Army committed south of Staraya Russa. |

| 15–18 February | A Soviet airborne battalion parachutes inside the Demyansk pocket. |

| 22 February | Hitler declares Demyansk a Festung. |

| 25 February | 1st GRC and Group Ksenofontov link up, thereby isolating II AK in the Demyansk pocket. |

| 2 March | Hitler approves Operation Brückenschlag to relieve Demyansk pocket. |

| 6 March | Soviet 1st Airborne Corps begins infiltration attack into Demyansk pocket. |

| 18 March | 34th Army and a parachute brigade launch a coordinated attack on Lychkovo, but are repulsed. |

| 19 March | Soviet paratroopers conduct a raid on the Demyansk airfields but are repulsed. |

| 21 March | Korpsgruppe Seydlitz begin relief Operation Brückenschlag. |

| 14 April | Korpsgruppe Zorn launches Operation Fallreep to break out towards relief force. |

| 21 April | Seydlitz’s relief force links up with SS-‘Totenkopf’ near Ramushevo. |

| 22 April | First supplies reach Demyansk through the corridor. |

| 3–17 May | First Soviet offensive against Ramushevo corridor. |

| 5 May | XXXIX Panzerkorps breaks through 3rd Shock Army to relieve Kholm. |

| 17–24 July | Second Soviet offensive against Ramushevo corridor. |

| 10–21 August | Third Soviet offensive against Ramushevo corridor. |

| 27 September to 5 October | German Michael counteroffensive widens Ramushevo corridor. |

| 17 November | Timoshenko takes command of North-western Front. |

| 28 November to 12 January | Fourth Soviet offensive against Ramushevo corridor. |

| 1943 | |

| 31 January | Hitler authorizes evacuation of Demyansk salient. |

| 15 February | Fifth Soviet offensive against Ramushevo corridor. |

| 17 February | The Germans begin evacuation of Demyansk salient. |

| 28 February | German evacuation of the salient is complete. |

| 1944 | |

| 21 February | Kholm liberated by Red Army. |

The commander of Heeresgruppe Nord during the Demyansk–Kholm campaign was initially Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb but he was soon succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall Georg Wilhelm von Küchler. Both commanders gave the priority of their attention to operations around Leningrad and tended to delegate much of the operational responsibility to Generaloberst Ernst Busch. The German commanders in the Demyansk–Kholm campaign were not as well known as their peers on other fronts, but they were equally effective. It is important to note that despite being faced with a near-catastrophic situation, the leaders in AOK 16 demonstrated an ability to recover from setbacks that made the German Army so tenacious in defence in World War II.

Generaloberst Ernst Busch (1885–1945), commander of AOK 16 from January 1940. He was tasked with holding the difficult right flank of Heeresgruppe Nord, extending from Staraya Russa to Ostashkov. Busch first entered the Prussian Army in 1904 and served as an infantry company commander and battalion commander on the Western Front in 1918. He particularly distinguished himself in combat in Champagne in 1918, for which he received the Pour le Mérite. Busch was retained in the post-war Reichswehr and received General Staff training. Perceived by some as pro-Nazi, Busch rose rapidly once Hitler came to power, becoming a division commander in 1935 and a corps commander in 1938. He led VIII AK in southern Poland in 1939 and then AOK 16 against the French Maginot Line in 1940. Busch was a solid, if not terribly imaginative, commander.

General der Infanterie Walter Graf von Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt (1887–1943), commander of II AK inside the Demyansk pocket. He commanded II AK from 21 June 1940 until 28 November 1942. After entering the army in 1908, Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt served in World War I and was badly wounded as an infantry company commander at Verdun in 1916. Like Busch, he was retained in the Reichswehr and trained as a General Staff officer. He succeeded Busch as commander of 23. Infanterie-Division in 1938 and led this formation in the Polish and French campaigns. During the early stages of Barbarossa, he was awarded the Ritterkreuz der Eisernes Kreuz for his capture of Kovno. Like many Wehrmacht officers in Russia, Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt became ill during the winter of 1941–42 and was not at his best during the early phase of the encirclement battle. Nevertheless, Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt’s calm leadership during the worst days of the siege helped to maintain morale. His illness persisted and he was eventually sent home in late 1942 and died in early 1943.

Generaloberst Ernst Busch found the bulk of his AOK 16 either surrounded or hard pressed by near-encirclement by the end of February 1942. Despite this, he proved to be a solid commander in adversity and was rewarded for his steadfast leadership after the Demyansk campaign by promotion to Generalfeldmarschall and command of Heeresgruppe Mitte. However, he was still in command when the Soviet Bagration offensive obliterated Heeresgruppe Mitte in June 1944 and Hitler relieved him. (Author’s collection)

General der Infanterie Walter Graf von Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt, commander of II AK for the bulk of the Demyansk Campaign. (Author’s collection)

General der Artillerie Christian Hansen, commander of X AK, underestimated the Soviet ability to manoeuvre through frozen marshes and over icy lakes and, consequently, was surprised by the enemy breakthrough in January 1942. However, he recovered from his error and orchestrated a stubborn defence of Staraya Russa that held off all Soviet attacks and thereby determined the outcome of the campaign. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1971-035-88)

General der Artillerie Christian Hansen (1885–1972), commander of X AK since October 1939. Hansen was commissioned as an artillery officer in 1903 and later received General Staff training. During World War I, Hansen served primarily as a high-level staff officer on the Western Front. In the post-war Reichswehr, he rose steadily and was given command of 25. Infanterie-Division in 1936. He was still in command of this unit at the start of World War II, but it was assigned a defensive role in the Saar. Hansen’s first command experience in combat was leading X AK in the invasion of Holland in 1940, then in Barbarossa in 1941. Although he later succeeded Busch in command of AOK 16 in 1943, Hansen’s health was poor and he retired for medical reasons in 1944.

SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Waffen-SS Theodor EickeBarbarossa