David Bullock • Illustrated by Ramiro Bujeiro

Series editor Martin Windrow

INTRODUCTION

TOWARDS NATIONHOOD

THE RUSSIAN FRONT, 1914–17

THE WESTERN FRONT, 1914–19

THE ITALIAN FRONT 1917–19

RUSSIA: REVOLT AND CIVIL WAR, 1917–18

THE SIBERIAN GARRISON, 1918–1920

LEGACY

FURTHER READING

PLATE COMMENTARIES

The title ‘Czech Legion’ first evoked international excitement in 1918, when this remarkable body of troops gave the Western Allies hope that a new Eastern Front could be opened against the Central Powers, while also seizing 6,000 miles of Russian territory along the railways from the Volga to the Pacific. The term was then set in concrete by the international press for three generations, and only recently has the more proper term ‘Czechoslovak Legion’ come into vogue in the West.

The Republic of Czechoslovakia, the new country that came into being in November 1918, was a fusion of two ethnic groups, the Slovaks as well as the Czechs. Moreover, the new state incorporated several other ethnicities, including Hungarians, Germans, Ruthenians, Poles and Jews. The latter three groups were represented among the volunteers who served individually or in small units with other national armies, from the United States and Canada to Serbia, as well as in the larger national Legions that fought in France, Italy and Russia.

The term ‘Legion’ in this connection was originally coined by the Czech Committee in London in autumn 1914, and in fact the legionaries tended not to use it, referring to themselves instead as ‘Brother Volunteers.’ However, after their return from Europe and Russia in 1919–20 the word ‘Legion’ took hold, becoming a reference of honour and an accolade that distinguished these expeditionary forces from the new Czechoslovak Army that had formed at home.

This book is a brief summary of the story of the 100,000 men who served in the expeditionary Legions: 10,000 in France, 20,000 in Italy, and 70,000 in Russia. They were volunteers from every corner of the world – farmers, craftsmen, students, intellectuals, deserters from the Austro-Hungarian Army, and soldiers of fortune. All were imbued with a sense of adventure; and, above everything, all were patriots fighting to place the state of Czechoslovakia on the map of Europe. Understanding that only the defeat of the Central Powers could achieve that cherished goal, they were among the most steadfast and determined of all the volunteers for the Allied forces.

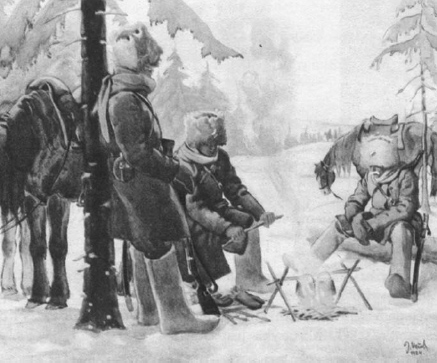

A painting by the Czech artist J. Koci, symbolizing national continuity. It depicts the one-eyed Bohemian hero Jan Zizka, centre, who led the Hussite armies to victory against the German and papal power of the Holy Roman Empire in 1420–24; symbols associated with him are the Holy Chalice flag of the followers of Jan Hus, and the mace of command. Zizka is depicted atop one of the Hussite ‘war wagons’, flanked by a rebel armed with a spiked flail – two improvised weapons that proved remarkably effective. Zizka, who died of disease in 1424, achieved the same semi-mythical status among the Czechs that William Wallace enjoys among the Scots. In the right background are figures wearing the uniforms of the expeditionary legions serving in France, Italy and Russia, and a flag of the aspirant state of Czechoslovakia approved by the Czechoslovak National Council in 1916: white over red, with the arms of the lands of the old Bohemian kingdom in the corners – Bohemia, Slovakia, Silesia and Moravia. (Author’s collection – as are all other images used in this book, unless specifically credited otherwise)

From their advent in the European heartland in the 5th century AD until the final cataclysmic events of World War I, the Czechs and Slovaks struggled to survive against more powerful neighbours and, periodically, to create a nation of their own. Briefly united as peoples in the Moravian Empire from the 9th century until that empire’s destruction at the hands of the Magyars in the 10th, the Czechs and Slovaks then went their separate ways. Thereafter the Czechs developed their own Bohemian kingdom, while the Slovaks fell under the yoke of the Magyars and the newly established kingdom of Hungary. In the 950s AD the Bohemian kingdom became a fief of the Holy Roman Empire under Otto the Great.

The ‘Golden Age’ of Czech history occurred from 1342–1378, centred on the reign of Charles IV of Bohemia. This king created the archbishopric of Prague, built the ‘New Town’ that made Prague into an imperial city, founded Charles University, and reconstructed the royal seat at Hradcany Castle. However, chaos followed his death, and two Protestant reform movements challenged Papal and Imperial authority in the early 1400s, the ‘Hussites’ and the ‘Taborites.’ Jan Hus perished at the stake in 1415, his followers taking up his name and joining a Protestant fundamentalist group known as the Taborites. These and other Czech allies, including a majority of the Bohemian nobility who sought to reduce the growing ‘German’ power of the Empire, rose in rebellion against the emperor in 1420. Led by the formidable Czech hero Jan Zizka, a one-eyed warrior who had fought against the Teutonic Knights at Tannenberg, the Hussites in their armed and fortified ‘war wagons’ repeatedly thrashed internal enemies and the Imperial forces sent against them; and although this epic chapter finally ended in internecine strife in 1434, the Hussite religious movement survived as the Reformed Church of Bohemia.1

In 1526 an Ottoman army destroyed the army of King Louis II of Hungary at the battle of Mohacs. As a consequence, the Habsburg dynasty based in Vienna was able to incorporate the Slovak portion of Hungary into the Holy Roman Empire, and Czechs and Slovaks would remain under Habsburg rule during nearly 400 more years. The Reformation period of 1517–1648 once again pitted the Protestants of various reformed creeds against the pope and emperor; it was the Czechs of Bohemia who in 1618 opened the first phase of what would be known as the Thirty Years’ War, but they were decisively defeated at the battle of White Mountain on 8 November 1620. The greatest achievement of the Czechs and Slovaks in these centuries perhaps lay merely in the survival of their language and folk traditions.

Two phenomena coalesced in the first half of the 19th century to produce a national revival of the Czechoslovaks: a tide of nationalism within the European empires, and the Romantic cultural movement. Nationalism defined the basis of a people by their language and their distinct cultural traits and affinities, while Romanticism helped nourish the dream and inspire the call to action. Both Czechs and Slovaks rose during the almost Europe-wide ‘Year of Revolutions’ in 1848, and both were crushed at the point of the bayonet. The new Habsburg emperor, Franz Joseph, determined to rule as an absolutist, but Austrian defeats in Italy in 1859 and by the Prussians in 1866 compelled him to strike an accord with the Hungarians. In 1867 the Dual Monarchy or Austro-Hungarian Empire was established, creating in effect two kingdoms ruled by a common emperor. Each half of the Dual Monarchy, however, strove to stifle the growing nationalism of its subject peoples – the Austrians repressing the Czechs, and the Hungarians the Slovaks. Nevertheless, while the Austro-Hungarian regime was reactionary in spirit it was not totalitarian in method, and progress towards a realized national consciousness was patiently maintained.

Contacts between Czechs and Slovaks intensified during the 1890s, especially at the intellectual level; students at the University of Prague formed the Czechoslovak Union, and in 1898 began publishing the journal Hlas (‘Voice’). The most important of the new political entities to arise was the Czech Progressive Party founded by Professor Tomas Garrigue Masaryk in 1900. Masaryk – who would become the ‘George Washington’ of his country, and the first president of independent Czechoslovakia – was well suited to the role. Born in Moravia to a working-class family in 1850, he had a Czech mother and a Slovak father. In 1882 he was appointed to a professorial chair at the University of Prague, where he became influential in intellectual circles before serving two terms in the Austrian Reichsrat (parliament). The Progressive Party that he founded sought national autonomy within the Empire while adhering to parliamentary procedures, rejecting radical solutions, and promoting universal suffrage.

Two other men were instrumental in the political realm in the years immediately before World War I. Edvard Benes, who would become the second president of Czechoslovakia, was born in Bohemia in 1884; in 1912 he became a professor at Charles University in Prague, and espoused the theory that the Czechs and Slovaks shared essentially the same ethnicity. His ideals were embraced by his student Milan Stefanik, a Slovak son of a Lutheran pastor. Born in 1880, Stefanik received his Doctorate of Philosophy in 1904, going on to achieve international acclaim and world travel as an astronomer. In 1912 he became a French citizen, a choice that later positioned him admirably to serve his nation’s cause.

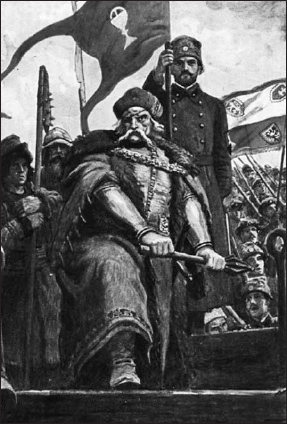

Art card honouring two men who were instrumental in the foundation of Czechoslovakia: Prof Tomas G. Masaryk, first president of the Czechoslovak Republic, and American President Woodrow Wilson. Some 40,000 Americans of Czechoslovak descent are believed to have served either in the volunteer legions or in the Allied national armies, and President Wilson himself remained warmly sympathetic to Czechoslovak national aspirations. In the centre, a legionary stands victorious, at his side the Lion of Bohemia and at his feet the stricken Germanic eagle.

Another potent and grass-roots element, the Sokol (Falcon) Movement, also played its role in the popular polemical debate. Founded in 1862 in Prague, the Sokol was partly a Slavic youth movement, partly a gymnastics and sports club, and partly a moral and intellectual lecture centre. It eventually incorporated both sexes and all social classes; in addition to marches, athletic drills, weight-lifting and fencing, the Sokol provided a library that illuminated Czech history and national mythology, and published its own journal. Members wore a unique uniform that reflected a certain debt to both Slavic and Romantic traditions – a white Montenegrin cap, red Garibaldi-style shirt, a Polish-style revolutionary jacket and brown Russian trousers – and flew a red flag emblazoned with a white falcon. Many members originally belonged to the Young Czech Party that tried to break with the old habits of compromise and to encourage more immediate reform; privately, members of the Sokol began referring to themselves as the ‘Czechoslovak National Army.’

Understanding the political ramifications of this increasingly popular movement, the Austro-Hungarian authorities disbanded the Sokol clubs in 1915 after the outbreak of World War I. However, former members would continue to serve the cause of nationalism by encouraging desertion from the Austro-Hungarian armies, and many Czechoslovak legionaries in the expeditionary forces of the Allied armies were former members of the Sokol.

After the guns of August sounded in 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire lined up with the German and Ottoman Empires against Russia, France and Great Britain. The Great War was the world-changing event that the Czechoslovaks had dreamed about, the chance to attain nationhood. For this to happen the Austro-Hungarian Empire would have to collapse and its allies would have to be defeated; the Czechoslovaks needed to make a military contribution to the Allied war effort and earn international recognition for their aspirations.

Milan Rastislav Stefanik in the uniform of a French general. After attaining an international reputation in astronomy, Dr Stefanik became a French citizen in 1912 and a pilot and meteorologist in the French Army in early 1915, acting as a key link between Masaryk, Benes and the Allies. Stefanik made several tours of the Legion fronts in France, Italy and Russia, promoting trust and goodwill between the legionaries and their host governments, and facilitating recruitment.

1 See Men-at-Arms 409, The Hussite Wars 1419–36