Introduction

The early years, 1807– 47

The hours of destiny, 1848 –60

Later years, 1861– 82

Opposing commanders

Inside the mind

A life in words

Bibliography

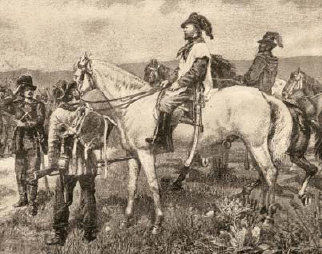

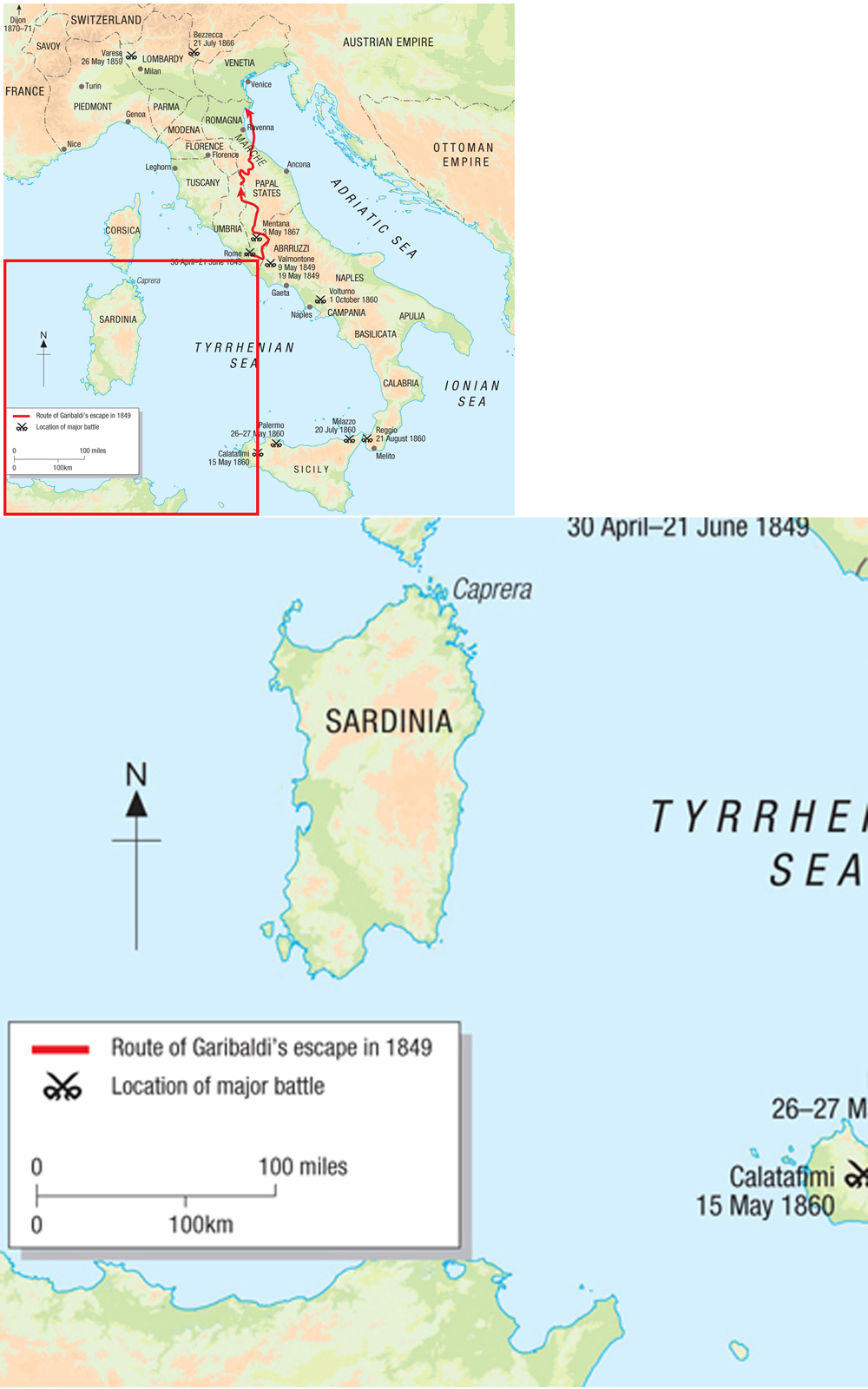

The military genius of Giuseppe Garibaldi was defined on a high hill near Calatafimi in Sicily on 15 May 1860, when his poorly armed volunteers, known as i Mille (‘the Thousand’), faced Neapolitan regular light infantry for the first time. Moving among his foremost troops, who were sheltered behind a terraced wall halfway up the hillside, Garibaldi waited to launch a decisive assault. As he bent low to negotiate a gap in the wall, a small piece of rock hit him on his back. Realizing that the enemy was running out of ammunition and was resorting to throwing rocks, he ordered a charge and clambered up the bank waving his sword, urging his men to follow. The garibaldini scrambled after him towards the crest of the hill where they were met with volley fire from the Neapolitan infantry, followed by a further hail of rock. As the two desperate bodies of men clashed, the musket butt and bayonet exacted a deadly toll, but soon the enemy fell back, rushing headlong towards Calatafimi. At that moment Garibaldi and his volunteers realized that they could take on and defeat Neapolitan regular troops. The struggle for Italian independence in 1860 had reached a turning point. By November of that year the Bourbon hold on Southern Italy had completely collapsed and within ten years the unification of the whole of Italy had been achieved.

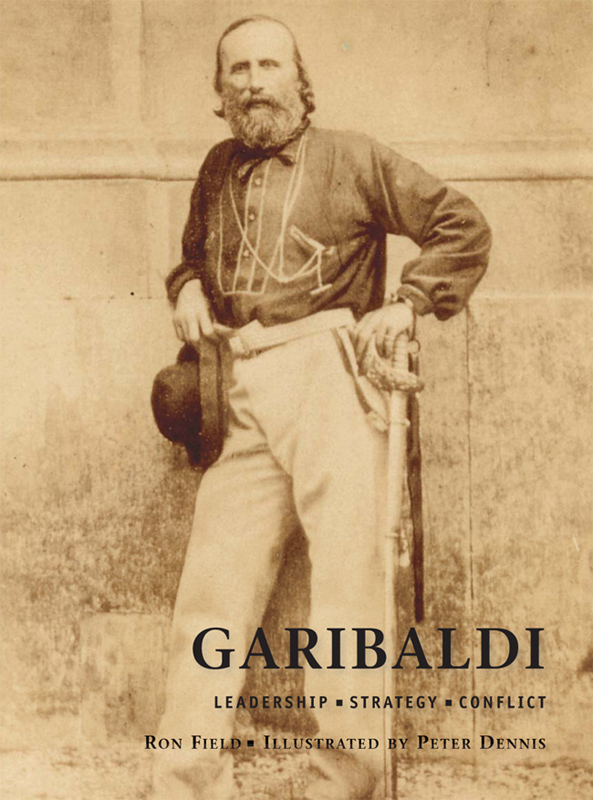

With his black lieutenant Andrea Aguyar mounted by his side, Garibaldi is saluted by republican troops near Velletri during the defence of Rome in 1849. He wears the white mantle or cloak that often protected him from spent enemy musket balls during the height of battle. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection)

Garibaldi began his military career on the plains and coastal waters of Brazil and Uruguay in South America, where he first rode with rebel gauchos during the struggle for independence for the Republic of Rio Grande do Sul, and later commanded the small Uruguayan fleet against the Argentine-backed forces of Manuel Oribe. Involved in numerous actions during the latter struggle, notably at San Antonio, he gained a worldwide reputation as a formidable commander of soldiers and sailors.

With the outbreak of revolution in Europe in 1848, Garibaldi returned with his Legion to the Old World to realize his lifelong aim of liberating and uniting the people of the Italian peninsula. Despite his courage and inspired leadership during fighting against the French in the Pamphili Gardens, at Velletri and at Villa Corsini, the Republic of Rome fell in 1849 and Garibaldi escaped into the Alban hills offering only ‘hunger, cold, forced marches, battles and death’ to those that followed. After about five years living as a fugitive, ex-patriot and mariner he settled on the island of Caprera, north of Sardinia, where he watched and awaited events in Italy. His military reputation amongst the Austrians as ‘Rötheufel’ (‘red devil’) was revived and further enhanced by the skill with which he commanded the Cacciatori delle Alpi, or Alpine Chasseurs, whilst fighting against the Austrians in the foothills of the Alps in 1859. The following year brought the long-awaited opportunity to invade Sicily and southern Italy, ruled by Francis II and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. At the head of his red-shirted Legion, ‘the General’ achieved stunning victories at Calatafimi, Palermo and Milazzo against a poorly commanded Neapolitan Army, following which he led his growing force across the Straits of Messina to Calabria on the Italian mainland. There, in October 1860, he defeated an army twice the size of his own at Volturno, and finally proved his full worth as a battlefield commander and tactician.

Published in 1889, this engraving depicts Garibaldi as he looked in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1846. He wears an example of the scarlet blouse for which his Italian Legion, and later ‘the Thousand’, became famous. (Author’s collection)

Despite assuming the title of ‘Dictator’ based on his victories in Sicily, Garibaldi relinquished control of his newly won territory, handing it over to Vittorio Emmanuele II, who annexed Southern Italy in November 1860 and assumed the title of King of Italy. The years 1861–70 were filled with further, but less successful, attempts at military conquest as Garibaldi rallied support for the continued struggle, not only for the unification of Italy, but for all European nationalities. He established the International Legion with ambitions of ridding Europe of autocratic rule from ‘the Alps to the Adriatic’, and hoped to use his powers as a Freemason and politician to further those ends. But his efforts in battle were less successful. During further failure to capture Rome, he was shot in the foot at Aspromonte, in southern Italy, in 1863, and wounded in the leg at Mentana in 1867. Nonetheless, he achieved the only Italian victory of the Austro-Prussian War at Bezzecca in Trentino during 1866, and saw his last battlefield action when he put old animosity behind him and volunteered his services to the newly formed Third Republic, commanding the French Army of the Vosges during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71.

According to the eminent British historian A. J. P. Taylor, Garibaldi was ‘the only wholly admirable figure in modern history’. For his battles on behalf of freedom in Latin America, Italy and France he was dubbed the ‘Hero of Two Worlds’. When editing Garibaldi’s Memoirs in 1860, Alexandre Dumas qualified this by stating: ‘A man who defends his own country or attacks another’s is no more than a soldier… But he, who adopts some other country as his own and makes offer of his sword and his blood, is more than a soldier. He is a hero.’ The Communist revolutionary leader Karl Marx was more cynical, referring metaphorically to Garibaldi as a mercenary or ‘taxi driver’ who gifted the crown of Italy to Vittorio Emmanuele II via his victories in 1860. Whatever view is taken, Garibaldi understood how to inspire men on the battlefield. He proved himself to be an able tactician and, most importantly of all, was able to lead the bayonet charges at Calatafimi and Volturno that tipped the scales of battle and led to ultimate victory.

Born in Nice, the capital of the French department of Alpes-Maritimes, on 4 July 1807, Giuseppe Garibaldi was the second of five children born to Domenico and Rosa Garibaldi. Following in the footsteps of his father, whose ship plied a trade in oil and wine along the Ligurian coast of Italy, Giuseppe was destined to go to sea and served aboard various vessels, sailing the trade routes of the world from 1824 until 1833. While moored at Taganrog, Russia, in April 1833, by which time he was a mate aboard the brig La Clorinda, he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo, a political immigrant from Oneglia, Italy, and member of the secret movement known as La Giovine Italia or ‘Young Italy’. Founded by Genoese philosopher and politician Giuseppe Mazzini in 1831, the aim of this organization was to achieve the unification of Italy as a liberal republic. Convinced to join this society, Garibaldi dedicated the rest of his life to the struggle for the liberation of his homeland from Austrian dominance. Garibaldi finally met Mazzini at Geneva in November 1833. Joining the Carbonari (‘charcoal burners’) revolutionary association, he was encouraged to leave the merchant service and enlist in the Royal Piedmontese Navy in an effort to spread mutiny in its ranks. When a planned insurrection in Genoa was discovered during February 1834 he fled to Marseilles, following which he was sentenced to death in absentia by a Genoese court.

Finding his way to Brazil via Tunisia under the assumed name ‘Joseph Pane’, Garibaldi took up the cause of independence of the republic of Rio Grande do Sul, and joined the gaucho rebels known as the farrapos (‘tatters’ or ‘rags’), who were fighting to free themselves from Brazilian rule. During this conflict he met Ana Ribeiro da Silva, better known as Anita. In October 1839 she joined him on his ship, the Rio Pardo, and a month later she fought at his side in the battles of Imbituba and Laguna. In 1841 the couple moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where Garibaldi worked as a trader and teacher of mathematics. They married the following year, eventually producing four children – Menotti, Rosita (who died aged four), Teresa and Ricciotti.

Incapable of settling down for too long, Garibaldi took up the cause of the recently established Republic of Uruguay when it was threatened by the conservative forces of Manuel Oribe, which were backed by the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel Rosas in 1842. Forming a legion of Italian ex-patriots known as the Italian Legion, he helped defend the city of Montevideo against the forces of Oribe until 1848. His Legion adopted a flag with a black field, representing Italy in mourning, with Vesuvius at its centre symbolizing the dormant power in their homeland. Although there is no contemporary mention of the garment, it is believed that the Italian Legion first wore red shirts as part of their uniform in Uruguay, having obtained them from a mercantile house in Montevideo where they were intended for export to the slaughtering and salting establishments for cattle at Ensenada and other places in the Argentine provinces. Camouflaging the blood of men rather than animals, the red shirt was to become the symbol of Garibaldi and his followers throughout many of their campaigns and battles in South America and Europe.

This scene from the ‘Garibaldi Panorama’ by Englishman John James Story depicts the aftermath of the battle that took place on the river Paraná in June 1842 between the Uruguayan flotilla commanded by Garibaldi and the naval forces of Manuel Oribe. After running out of ammunition for his guns, Garibaldi was forced to order his vessels burned while their crews escaped ashore in small boats. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection)

Helped by his old and experienced friend, Francesco Anzani, who was a far more capable organizer than himself, Garibaldi trained the Legion to become a skilful and dedicated fighting force. He instilled in them the belief that they were not merely fighting for the independence of Uruguay but for the future of their own country. In 1845 he occupied Colonia del Sacramento and Isla Martín García, and led the controversial sack of Gualeguaychú. Displaying the courage in the heat of battle for which he gained renown, he achieved important victories at Cerro and San Antonio. At Cerro on 17 November 1845 he bravely led the Legion in a charge in order to retrieve the body of a republican officer who had wandered into enemy lines. Similarly, at San Antonio in 1846, about 150 men of his Legion made a stand against 1,200 cavalry and 300 infantry. After hours of murderous mêlée under a scorching hot sun, during which Garibaldi had his horse shot from under him but remained personally unscathed, he led a night-time bayonet charge that shattered the enemy lines and succeeded in linking up with reinforcements. News of these brave deeds was spread by Mazzini in papers such as L’Apostolato Repubblicano, and the fame of the Italian Legion and its inspired commander spread throughout Europe.

Garibaldi became a Freemason during his time in South America, taking advantage of the asylum its lodges offered to political refugees of European countries governed by despotic regimes hostile to democratic or nationalistic movements. This development was to have a major influence on both his military and political career, particularly from 1860 onwards. In Montevideo during 1844 he was initiated by an irregular lodge not recognized by the main international Masonic movement. Later the same year he regularized his position by joining the Les Amis de la Patrie lodge of Montevideo under the Grand Orient de France. He subsequently attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850 and London in 1853–54, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism whose anti-papal stance was influenced by socialism.

Despite fame and success in South America, the fate of his homeland continued to concern Garibaldi. The election of the liberal Pope Pius IX in 1846 caused a sensation among Italian patriots, both at home and in exile. When news of the Pope’s initial reforms reached Montevideo, Garibaldi wrote the following letter, dated 12 October 1847: ‘If these hands, used to fighting, would be acceptable to His Holiness, we most thankfully dedicate them to the service of him who deserves so well of the Church and of the fatherland. Joyful indeed shall we and our companions in whose name we speak be, if we may be allowed to shed our blood in defence of Pius IX’s work of redemption.’

In 1847 Garibaldi offered Gaetano Bedini, the apostolic nuncio at Rio de Janeiro, the service of his Legion for the liberation of the Italian peninsula. News of the outbreak of revolution in Palermo in January 1848, and revolutionary agitation elsewhere, encouraged Garibaldi to at last lead some 60 members of his Legion home to begin the fight for the unification of Italy.

The revolution in Italy began in September 1847 when riots inspired by liberals broke out in Reggio Calabria and Messina in the south and were put down by the troops of Ferdinand II, King of the Two Sicilies, who earned the nickname ‘Re Bomba’ (‘King Bomb’) for ordering the bombardment of Messina and Palermo at that time. On 12 January 1848 a rising in Palermo, Sicily, against the rule of Ferdinand spread throughout the island and served as a spark for revolution throughout the Italian peninsula, which spread throughout much of Western Europe. Landing at Nice, his birthplace, in April 1848, Garibaldi offered his services to the liberal Charles Albert, King of Sardinia, who was attempting to oust the Austrians from Piedmont and Lombardy in northern Italy. Faced with rejection at Genoa, Garibaldi accepted a commission under the weak provisional government of Milan in Lombardy and was sent with a small and poorly armed force to Bergamo, only to learn that disaster had befallen the main royalist army. Completely routed at Custoza on 25 July, the forces of Charles Albert retreated to Milan, where an armistice was signed with the Austrians.

Feeling betrayed but not defeated, Garibaldi determined to carry on the struggle against Austria in the Alps and waged a short campaign in the mountain villages around lakes Maggiore and Varese from 14 August 1848. Although driven across the Swiss border by 27 August, he displayed his genius for guerrilla warfare for the first time on the Italian peninsula during small actions near Morazzone, and ensured for himself the future support of revolutionaries throughout Italy.