Gordon Williamson • Illustrated by Ramiro Bujeiro

CONTENTS

Introduction

Military Auxiliaries: Army & Armed Forces

Navy

Air Force

Civil & Political Auxiliaries

The Plates

AS A GENERAL RULE, during the greater part of the Third Reich period in Germany the employment of women in anything other than traditional roles (secretarial, clerical, etc.) was looked upon with a certain degree of disapproval. Hitler’s very narrow-minded view of women saw their place as firmly in the home, caring for husband and children – in the latter case as many as possible, with official state decorations (the Mother’s Cross or Mutterkreuz) instituted to reward women for producing as many babies as possible for the Fatherland. Hitler’s strictly domestic view of the German woman’s role in society naturally proved untenable; a wartime economy demanded ever more workers for the factories as able-bodied men were called up for military service at the front. Before long women were taking their place in what traditionally had been male occupations, at first in industry and then in uniformed services. Their new roles could be as varied as working as tramcar conductors, signals operators in the armed forces, or crewing searchlights in the anti-aircraft defences. There were even a few examples of women being awarded military decorations for bravery; but women in the Third Reich were never put in the position of serving at the front in a combat capacity, unlike their counterparts in the Soviet Union where women became fighter pilots, tank drivers and even snipers.1

A wartime image showing a female auxiliary of the State Railways (Reichbahn). Such posters and other illustrations always showed the jobs as far more glamorous than they were in reality. (Otto Spronk)

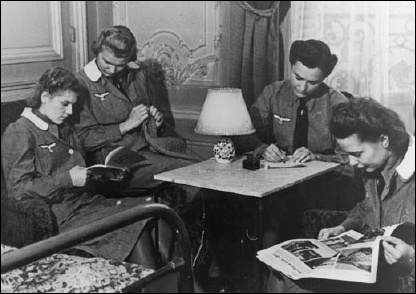

Group of Army Signals Auxiliaries (Nachrichten-helferinnen des Heeres) posed at their ease. Note the work smocks, with removable white collars, worn over the grey blouse, both garments with the Army style national eagle and swastika emblem on the right breast. See Plate B1. (Courtesy Brian L.Davis)

1 See Elite 90, Heroines of the Soviet Union 1941–45

Despite the fact that the use of female auxiliary staff by the Army had a long history dating back to the days before World War I, the order issued on 12 March 1937 for the mobilisation of the Army (Heer) made no provision for the resumed recruitment and employment of women. This was no doubt partly due to the belief that the principles of the Blitzkrieg would be vindicated, and any conflict would be of such short duration that the need for female auxiliaries would not arise. There is equally little doubt that the decision was also influenced by Hitler’s very firm views on the place women should hold in German society.

Army Nachrichtenhelferin. The brooch worn on the tie is seen to good effect here. Note the piping in the front ‘scallop’ of the field cap flap, and the placement of the national emblem on the flap rather than the crown. Although the left sleeve with its rank insignia cannot be seen, under magnification the yellow piping to the cap seems to have a twisted cord effect, which would make her an Unterführerin under the 25 March 1942 regulations. (Otto Spronk)

It was after the successful conclusion of the campaign in the West, with France subjugated and more than half occupied, that the need for substantial numbers of additional personnel in the form of female auxiliaries became fully apparent. The administration of the occupied territories fell predominantly to the Army, and the need arose to fill huge numbers of clerical and administrative posts – positions that were considered perfectly suitable for women. The use of female auxiliaries in such posts would also release manpower for fighting units. Under the regulations of the day, such female staff would be considered as civil servants attached to the Army.

Accordingly, on 1 October 1940 the Corps of Female Signals Auxiliaries (Nachrichtenhelferinnen) was formed. This was to prove only the forerunner of a number of other female branches: the Corps of Welfare Auxiliaries (Betreuungshelferinnen) in 1941, the Corps of Female Staff Auxiliaries (Stabshelferinnen) and Economics Auxiliaries (Wirtschaftshelferinnen) in 1942, and even Female Horse-Breakers (Bereiterinnen) in 1943. Although a significant number of volunteers for such auxiliary service came forward, demand quickly outstripped supply. New laws were passed in December 1941 introducing the concept of compulsory military service (Dienstverpflichtung) for women between the ages of 18 and 40 years. These laws were never robustly enforced, however, probably once again under the influence of Hitler’s negative views on women as soldiers. Finally, on 29 November 1944, the auxiliaries serving with all three branches of the Armed Forces (Wehrmacht) were combined into a single Corps of Female Auxiliaries (Wehrmachthelferinnen).

Women in the German Army found themselves in a rather ambiguous situation. They were considered to be subject to the full range of military law and military discipline, yet did not have the legal status of soldiers. The Wehrmacht high command made it clear that as a matter of principle women should not be involved in fighting with firearms or serve in what might be considered ‘combat’ situations. This stand was in fact relaxed in certain cases: many women served in what might be termed a combat role in the anti-aircraft defences, and others served as signals staff with front line formations outside Germany. Women who wore military uniform were subsequently granted the legal status of combatants by an order of 28 August 1944.

Problems in maintaining sufficient supplies of uniforms for women auxiliaries resulted in 1942 in a decision that in general only women serving as Armed Forces Auxiliaries outside the German Reich would wear uniform. Thereafter, women serving in Germany would wear not the uniform of the Wehrmacht but rather a protective smock or overall.

A small number of female auxiliaries were decorated with the Iron Cross for bravery, usually relating to carrying out their duties under enemy fire, or helping to save wounded comrades, in the closing stages of the war. It is not known in which of the three branches of the Wehrmacht the following Stabshelferin and Nahchrichtenhelferin served: Stabshelferin Hildegard Wollny, Wehrmachthelferinnen Alice Bendig and Hildegard Bollgardt (March 1945); Nachrichtenhelferin Margarete Hirsekorn (April 1945). There is also a record of a Freiwillige or Volunteer named Leni Stalinek being decorated with the Iron Cross in March 1945, and another, Erika Stollberg, as late as May 1945. Again, details of their service are not known.

Taken in order of their formation, the following brief review of each of the branches explains their purpose and duties.

Heeresmiteillungsblatt 40, No.1085, established the Auxiliary Signals branch on 1 October 1940. Throughout its brief history this branch was staffed by a mixture of transferees from other female organisations such as the Red Cross, by volunteers, and eventually by conscripts.

The basic unit for these auxiliaries was the Kameradschaft, comprising one supervisor (Oberhelferin) and up to 11 auxiliaries (Helferinnen). Anywhere from two to five of such Kameradschaften would form a Zug, a unit roughly equivalent to a platoon and commanded by a woman of leadership grade (Führerin). From two to four such Züge would be formed into a Bereitschaft (equivalent to a company), commanded by a senior leader (Oberführerin). Even the names for these auxiliary units owed more to the terminology of civil and political organisations of the Third Reich than to that of the Wehrmacht – yet further evidence of their somewhat ambiguous status in the eyes of the high command.

Army Stabsführerin, with gold collar and cap piping and a single gold chevron to each collar point; the signals ‘Blitz’ patch on her upper left sleeve is also edged in gold cord. In the background to the right stands Wolfgang Lüth, the U-boat ace who would eventually be awarded the Knight’s Cross with Oakleaves, Swords and Diamonds. Cf Plate A2. (U-Boot Archiv)

Signals Auxiliaries were trained at the Army signals school at Giessen by male regular Army signals personnel. The trained auxiliaries were then given duties as radio operators, telephonists, switchboard operators and secretarial workers within communications units. They would serve in the occupied territories primarily at higher level commands such as Corps or Army headquarters; or at general administrative centres of the Army. Many wartime photographs will be encountered showing both Army Nachrichtenhelferinnen and Navy Marinehelferinnen waiting, garlands of flowers in hand, to greet U-boat crews as they docked after particularly successful missions. These auxiliaries were also employed within the Reich where regular civil servant manpower was not available or suitable. On occasion Nachrichtenhelferrinen were also temporarily attached to other organisations such as Organisation Todt.

Army signals auxiliaries in summer shirtsleeve order of white blouse with grey skirt and cap. Note the black tie with its enamelled ‘Blitz’ badge and the small ‘Blitz’ worn on the left side of the field cap. The national emblem, woven in white on black, is worn on the blouse. Note also the regulation issue handbag slung on its shoulder strap. (U-Boot Archiv)

The basic service uniform of the Nachricht-enhelferin was a smart grey wool suit comprising skirt and tailored jacket, worn with a white blouse and black tie. Silk stockings and black lace-up shoes were worn, and a field cap completed the outfit. Auxiliaries were also provided with a leather handbag with a long shoulder strap.

Working smocks were also part of the regulation issue. A raincoat could also be worn in wet weather, and galoshes were also provided, while a greatcoat was issued for wear during cold weather. Additional items issued during the winter months included warm woollen underwear, woollen stockings and gloves, a scarf and ear muffs. In some areas ski trousers were worn as an alternative to the skirt, and fur waistcoats and mittens were used in extreme conditions.

Effectively, the uniform proper was used as walking-out dress, with the smock being worn for normal working duties. Women serving in occupied territories were forbidden to wear civilian clothing and fancy jewellery at any time, and only a minimal amount of make-up was permitted.

Uniform jacket The regulation jacket was double-breasted with two rows of two exposed buttons, the collar and lapels being relatively large. Two internally hung breast pockets were provided, with shallow-pointed external button-down flaps. On the right pocket flap was a machine-woven national emblem in white on a black background. Vertical slash waist pockets were closed by an exposed button in line with the lower front buttons. On each sleeve, some 4cm up from the cuff, was a button-down pointed tab, its end sewn into the front sleeve seam and the pointed end towards the rear.

On the upper left sleeve was a vertical oval dark blue-green patch, measuring c42mm x 56mm and bearing in its centre a lemon-yellow lightning bolt signals badge or ‘Blitz’. This insignia gave these auxiliaries their common nickname of ‘Blitzmädchen’. The sleeve insignia for leadership grades was edged with lemon-yellow cord.