| MARK STILLE | ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT |

INTRODUCTION

ITALIAN NAVAL STRATEGY AND THE ROLE OF THE BATTLESHIP

ITALIAN BATTLESHIP DOCTRINE

NAVAL TREATIES AND ITALIAN BATTLESHIP CONSTRUCTION

ITALIAN BATTLESHIP WEAPONS

ITALIAN BATTLESHIP RADAR

THE BATTLESHIP CLASSES

• Cavour Class

• Duilio Class

• Vittorio Veneto Class

ITALIAN BATTLESHIPS AT WAR

ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

One of the most misunderstood aspects of the naval war in the Mediterranean is the role of the Italian Navy’s capital ships. The commonly held perception is that they were committed only sparingly and, when faced with the British fleet, were always defeated. The actual story is far different and deserves proper attention. After entering the war, the Italians committed their battleships aggressively. Even after the disaster at Taranto, where several ships were placed out of action (but only one for the duration of the war), the Italians continued to employ their battleships as part of their strategy to retain control of the central Mediterranean. It was only late in the war, principally driven by fuel shortages, that the Italians ceased operations of their remaining capital ships. Ironically, the most dramatic loss of an Italian capital ship came at the hands of their former German allies when the Italians changed sides in September 1943. By the end of the war, three of the four rebuilt Italian battleships remained in service, together with two of the three modern battleships. This book tells the story of the seven Italian battleships that saw service between 1940 and 1943.

Between the wars, the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) considered the French Navy as its most likely opponent. Increasingly in the 1930s, as Italian foreign policy became expansionist, war with Great Britain was seen as inevitable. When Italy entered the conflict in June 1940 by declaring war on France and Great Britain, the Regia Marina was not ready for war. This did not matter to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who judged that he had entered into the final stages of a brief conflict and that Italy was on the winning side. Given this perception, the Italians were loath to risk their fleet. The generally cautious Italian naval planners were also driven by the fact that losses to the fleet, especially battleships, could not be readily replaced by Italy’s weak maritime industry. Thus, in essence, the Italians had no incentive to risk their fleet in a short war.

Going into the war, the Regia Marina had several primary missions. Foremost was maintaining communications with Libya in North Africa and the Balkans. This required the movement of regular convoys to those areas. Another important task was the control of the central Mediterranean, thus denying its use to the British. This was a key strategic factor during the war, as it dramatically increased the shipping requirements to maintain British forces in the Middle East. Unable to use sea lanes through the Mediterranean, the British were forced to use the Cape of Good Hope route around Africa, a total distance of 12,000 miles. This quadrupled shipping requirements compared with the Mediterranean route and had strategic implications for Allied capabilities and plans worldwide. Instrumental to being able to move convoys to Africa and keeping the Mediterranean closed to Allied shipping was the maintenance of Italy’s battle fleet.

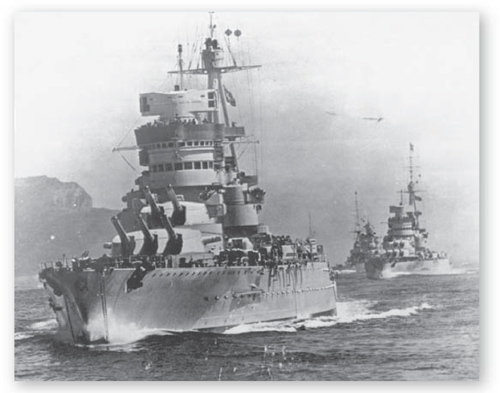

Cavour leading Cesare in a line ahead in 1938. When the Italians entered the war in 1940, these were the only two operational battleships available to engage the British Mediterranean Fleet. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

However, even within this strategically defensive construct, the Regia Marina did anticipate employing its battle fleet against the British. Even in a short war, this was to be done as soon as possible, but only close to Italian bases in the central Mediterranean. The Italians did not foresee operations by their heavy units in the eastern or western Mediterranean. As the war became extended, the Regia Marina never abandoned these general intentions, except for a single foray into the eastern Mediterranean with disastrous results. While strategically the Regia Marina was essentially defensive, the Italians employed their battleships aggressively on the operational level to achieve their primary missions until the point where fuel shortages precluded operations by large ships. However, the fairly aggressive commitment of battleships on the operational level did not translate to comparable aggression on the tactical level, but overall it cannot be said that the Regia Marina cowered in harbor during the war.

By August 1940, both Littorio (foreground) and Vittorio Veneto were operational. Both are shown here conducting gunnery exercises. Together, these ships formed the most powerful battle squadron in the Mediterranean. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

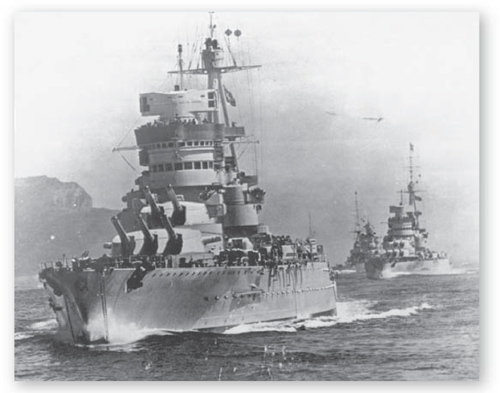

When Adolf Hitler made a state visit to Italy in May 1938, one of the highlights of the trip was an Italian naval review in the Bay of Naples on May 5. The centerpiece of the review were the two battleships of the Cavour class, shown here in the foreground steaming in a line ahead. Behind them are several heavy cruisers. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Regia Marina intended to fight its battles at extended ranges; in fact, most battles in the Mediterranean were fought in daylight with good visibility, which facilitated this doctrine. Several factors shaped the Italian desire to fight at extended ranges. Foremost was the superior range of Italian guns, which gave them the ability to engage at long ranges beyond the range of their enemies. Another key factor was the superior speed of all Italian battleships over their British counterparts. Theoretically, this permitted the Italians to keep the action at extended range. It also gave the Italians the ability to choose whether and when to break off an action. Finally, with the exception of their modern ships, the rebuilt Italian battleships possessed inferior protection compared with British battleships so this made the Regia Marina reluctant to close the range where British heavy units were more likely to deal punishing blows.

Italian doctrine for surface action called for fire to be opened at long range. Gunnery was conducted in a deliberate manner, with fire being adjusted after each salvo. Once the proper range had been found, the target would be engaged with rapid fire to inflict maximum damage. After the enemy force had been attritted, decisive combat at short range would ensue. Obviously this doctrine hinged on accuracy at long range. In the pre-radar era, it was difficult for any World War II navy to demonstrate consistent accuracy at extended range, but the Regia Marina was as good as any other navy in this respect.

The Italians had made little preparation for night-fighting and, if given a choice, preferred to end an action when darkness fell. This certainly held true for Italian battleships, which were not to be risked at night. This placed the Regia Marina at a severe disadvantage against the British, who stressed night-fighting.

The Washington Naval Treaty signed in February 1922 gave the Italians a tonnage allotment of 175,000 for battleships, comparable with the tonnage allocated to the French. The treaty set a displacement limit for battleships at 35,000 tons with guns no larger than 16 inches. These limits remained in effect until late 1936.

The first Italian dreadnought was Dante Alighieri, launched in 1910 and commissioned in 1913. She was fast and well armed for her time, but was deficient in armor protection. The ship provided a template for the next two classes of Italian dreadnoughts. Dante Alighieri was taken out of service in 1928 and scrapped the following year. (Ships of the World)

The end of World War I saw the Italians well under their maximum battleship tonnage. Only the unique Dante Alighieri, the two surviving units of the Conte di Cavour class, and the two Andrea Doria units were in service. Thus, the Italians were not required to scrap any of their existing battleships, and were actually permitted to build new units up to a total tonnage of 70,000 tons between 1927 and 1931. However, as long as naval budgets were constrained by poor economic conditions, and the French Navy made no move to build up to its allowed tonnage, Italian battleship construction was stagnant. The Italians chose to put their limited naval construction budget into heavy cruisers in the 1920s.

The Dante Alighieri was scrapped in 1928 and the two oldest units of the Cavour class were placed in reserve. In 1928, fearing reports of French construction of battleships, the Italian Admiralty asked the Naval Construction Office to submit plans for three 23,000-ton ships equipped with 15-inch guns. A subsequent design called for a ship with 16-inch guns. Since French battleship construction had not resumed, these plans were dropped, and a much larger design was chosen, which eventually became the Vittorio Veneto class.

Ships of the World)