Introduction

The early years

World War II, 1939–43

India and Burma, 1943–45

Opposing commanders

Inside the mind

When the war is done

A life in words

Further reading

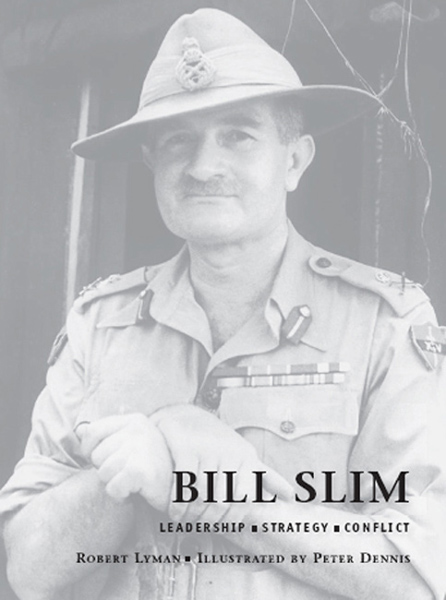

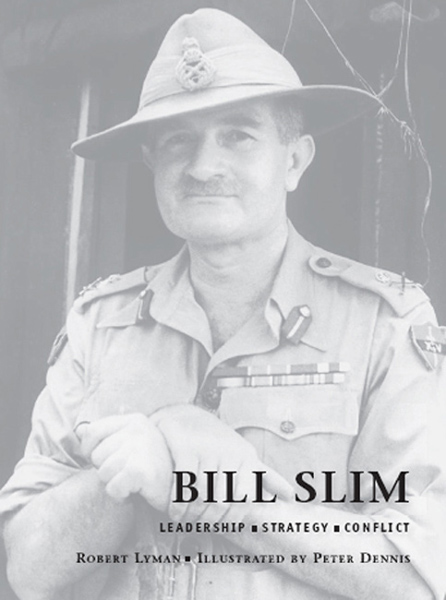

Every cadet at Britain’s Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst receives, on joining, a thin red volume entitled Serve To Lead. Bearing the motto of the Academy, the book distils the wisdom of past British military leaders (not all of whom are famous) on the subject of morale and leadership in war. For most cadets this is their first exposure to Field Marshal Sir ‘Bill’ Slim (he was never called William), the man responsible for destroying two Japanese armies during World War II, the first in India, around Imphal and Kohima, in 1944 and the second in Burma, around Meiktila and Mandalay, in 1945.

Every analysis of Slim’s achievements in Burma provides evidence of a remarkable military talent. Most are effusive in their praise for him as a military commander.

In a masterful summary of the higher command of the Burma Campaign, the historian Frank McLynn states:

There are solid grounds for asserting that when due allowances have been made… Slim’s encirclement of the Japanese on the Irrawaddy deserves to rank with the great military achievements of all time – Alexander at Gaugamela in 331 BC, Hannibal at Cannae (216 BC), Julius Caesar at Alesia (58 BC), the Mongol general Subudei at Mohi (1241) or Napoleon at Austerlitz (1805). The often made – but actually ludicrous – comparison between Montgomery and Slim is relevant here… there is no Montgomery equivalent of the Irrawaddy campaign. His one attempt to prove himself a master of the war of movement – Operation MARKET GARDEN against Arnhem – was a signal and embarrassing failure. Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius.1

The Old Edwardians Rugby Team 1913–14, Slim is second from left on the back row. In 1908 Slim joined King Edward’s School in Birmingham as a ‘pupil-teacher’ on a salary of 17 shillings and sixpence a week. King Edward’s served one of the poorest areas of industrial Birmingham. His intimate knowledge of the lives led by his young male pupils made him deeply aware of the impact of poverty on behaviour: it was said of Slim when he reached the elevated station of Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1947 that he had ‘never forgotten the smell of soldier’s feet’. (Viscount Slim)

And yet, in 1942 Bill Slim was a relatively unknown and not particularly successful Indian Army general who had just presided over the British Army’s longest ever retreat, 1,000 miles (1,600km) from Burma into India. How did he find himself in command of a triumphant, all-conquering army in India in 1944 and Burma in 1945? The story of the transformation of this army, from defeat into victory, the title of his best-selling war memoir in 1956, is not just the story of British arms in the Far East between 1942 and 1945, but the account of Slim’s rise to military greatness. At the end of the war he commanded the largest British military force ever assembled, and at Imphal in 1944 (to say nothing of Mandalay–Meiktila in 1945) had dealt what one Japanese commentator, a veteran diplomat, considered to be the greatest defeat Japan had ever suffered in its history.2

Slim was successful as a commander for two reasons. He was, first and foremost, a born leader of men. He was constantly mindful of the predicament of the men who had to fight battles designed by men who would often be far to the rear when the bullets began to fly. Slim instinctively knew that the strength of an army lies not in its equipment or its officers, but in the training and morale of its soldiers. His basic premise was:

That the fighting capacity of every unit is based upon the faith of soldiers in their leaders; that discipline begins with the officer and spreads downward from him to the soldier; that genuine comradeship in arms is achieved when all ranks do more than is required of them.… In battle, the soldier has only his sense of duty, and his sense of shame. These are the things which make men go on fighting even though terror grips their heart. Every soldier, therefore, must be instilled with pride in his unit and in himself, and to do this he must be treated with justice and respect.

Slim made tremendous efforts to communicate with his men, travelling vast distances to talk with them, simply and honestly, as man to man. He never engaged in histrionics or tricks of oratory and through these events his strong and attractive personality shone through. His firm view was that the most important attribute of a leader was his effect on morale, and he did everything he could to ensure that he was seen and trusted by his men. He inspired confidence because he related to the men as men, not as subordinates. He was the antithesis of the ‘château general’ who never ventured far from the comfort of his headquarters, far to the rear of the action. He brought his men into his confidence in a way that was very unusual at the time, the result of the complete absence in his personal make-up of any social pretension. Half a century after the war George Macdonald Fraser, the best-selling author of the ‘Flashman’ books, recalled Slim arriving at his battalion of the Border Regiment in Burma in 1945 for one of these talks:

The biggest boost to morale was the burly man who came to talk to the assembled battalion by the lake shore – I’m not sure when, but it was unforgettable. Slim was like that: the only man I’ve ever seen who had a force that came out of him, a strength of personality that I’ve puzzled over since.… His appearance was plain enough: large, heavily built, grim-faced with that hard mouth and bulldog chin; the rakish Gurkha hat was at odds with the slung carbine and untidy trouser bottoms.… Nor was he an orator.… His delivery was blunt, matter-of-fact, without gestures or mannerisms, only a lack of them. He knew how to make an entrance – or rather, he probably didn’t, and it came naturally… Slim emerged from under the trees by the lake shore, there was no nonsense of ‘gather round’ or jumping on boxes; he just stood with his thumb hooked in his carbine sling and talked about how we had caught Jap off-balance and were going to annihilate him in the open; there was no exhortation or ringing clichés, no jokes or self-conscious use of barrack-room slang – when he called the Japs ‘bastards’ it was casual and without heat. He was telling us informally what would be, in the reflective way of intimate conversation. And we believed every word – and it all came true. I think it was that sense of being close to us, as though he were chatting offhand to an understanding nephew (not for nothing was he ‘Uncle Bill’) that was his great gift.… You knew, when he talked of smashing the Jap, that to him it meant not only arrows on a map but clearing bunkers and going in under shell-fire; that he had the head of a general with the heart of a private soldier.3

Slim knew his men and could communicate with them because he was one of them, and, from the bloody days in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia during World War I and in the inter-war years on the North-West Frontier, had experienced their bitterest trials. ‘He understood men’ wrote the Australian journalist Ronald McKie, who met him in Burma. ‘He spoke their language as he moved among them, from forward positions to training bases. He had the richest of common-sense, a dour soldier’s humour and a simple earthy wisdom. Wherever he moved he lifted morale. He was the finest of Englishmen.’4 Frank Owen, the Fleet Street editor who watched him closely in India and Burma for two years, observed: ‘Slim does not court popularity, and he hates publicity. But he inspires trust. The man cares deeply for his troops, and they are well aware that their well-being is his permanent priority.’5

At Mandalay, April 1945. Savouring the moment of his victory, the battles of Meiktila and Mandalay in March 1945, Slim has every reason to be pleased at the utter destruction of Kimura’s army in what the latter called the ‘masterstroke’ of British strategy. Slung over his shoulder was an M1 carbine, given to him as a gift by General Joe Stilwell. (Alamy, B4WF7J)

In addition to giving them the mental and practical wherewithal to fight the Japanese, one of the most fearsome armies the British have ever had to face, Slim took many practical steps to improve his men’s health and welfare. His approach to the building up of the fighting power of an army – from a situation of profound defeat and in the face of crippling resource constraints – was built on the twin platforms of rigorous training and development of each individual’s will to win, through a deeply thought-out programme of support designed to meet the physical, intellectual and spiritual needs of each fighting man.

As a result the men of Fourteenth Army – British, Indian, African and Gurkha – gave him their loyalty in a way rarely seen in the annals of command. It would be inconceivable to think of Field Marshal Montgomery as ‘Uncle Bernard’, but it was in ‘Uncle Bill’ that soldiers in Burma, from the dark days of 1942 and 1943 through to the great victories over the Japanese in 1944 and 1945, put their confidence. Brigadier Bernard Fergusson observed that he ‘was the only Indian Army general of my acquaintance that ever got himself across to British troops. Monosyllables do not usually carry a cadence; but to thousands of British troops, as well as to Indians and to his own beloved Gurkhas, there will always be a special magic in the words “Bill Slim”.’6

Slim’s second legacy was his approach to warfare, which at the time was very different to received wisdom across the British armed forces. He was not a theoretician of war, although after the war he became for a short time Commandant of the Royal College of Defence Studies. Rather, he was an intensely practical strategist. At his heart he was a proponent of the maxim taught to him when he was a young officer by a hoary old sergeant-major: ‘Hit the other fellow as quick as you can and as hard as you can, where it hurts him most, when he ain’t looking.’7 Slim’s entire approach to strategy was to exploit his enemy’s weaknesses and so undermine his will to win. He did this successfully in Syria, India and Burma by concentrating force to achieve surprise, psychological shock and physical momentum. By so doing he attempted to achieve moral dominance on the battlefield over his enemy. It was an approach to war that sat in stark contrast to the idea of matching strength with strength, and force with force, where the goal of strategy was simply to slog it out with an enemy in an attritional confrontation of the sort expounded by less imaginative commanders (British and others) elsewhere during the war and, indeed, throughout history. Slim prized above all the virtues of cunning and guile, and he sought opportunities at every turn to trick and deceive his enemy. In the fighting in India and Burma this required realistic, physically demanding training; the use of air power to supply forward troops; new tactics to fight the Japanese; the delegation of command to the lowest possible level; a self-help approach to logistical deficiencies and a relentless exploitation of the pursuit, to ensure that an enemy caught off guard had limited opportunities to recover its equilibrium. The campaigns in India and Burma in 1944 and 1945 were to reward Slim’s approach to warfare with a victory that few if any in 1942 or 1943 foresaw.

Outside 10 Downing Street after a Cabinet meeting, 1950. Slim was a successful CIGS during the turbulent post-war period that included National Service, the establishment of NATO and the Korean War. (Corbis, U1156405INP)

‘Slim’s Lambs’, with Slim in the middle of the back row. While he was at King Edward’s his status as an uncertificated elementary teacher allowed him entry to the Birmingham University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), which he joined in 1912. He soon reached the exalted rank of lance-corporal. (Viscount Slim)

1. Frank McLynn The Burma Campaign (London: Bodley Head, 2010), p. 432.

2. Toshikazu Kase Eclipse of the Rising Sun (London: Jonathan Cape, 1951), p. 92.

3. George MacDonald Fraser Quartered Safe Out Here (London: Harper Collins, 1992), p. 37.

4. Ronald McKie Echoes from Forgotten Wars (Sydney: Collins, 1980) p. 117.

5. Frank Owen ‘Slim’ in Phoenix Magazine (New Delhi: South East Asia Command, 1945).

6. Lord Ballantrae ‘Slim’ The Army Quarterly, (Volume 4, 1971), p. 268

7. William Slim Defeat into Victory (London: Cassells, 1956), p. 551. All other unattributed quotations from Slim are taken from this work.

Slim had always wanted to be a soldier, but his birth in 1891 into a lower middle-class family in Bishopton, Bristol, would have stifled these ambitions were it not for the onset of World War I. By this time his family was living in Birmingham, and after leaving King Edward’s School the young Slim had found himself teaching at a primary school before, in 1910, beginning work as a clerk in Stewarts & Lloyds, a metal-tube maker. Military aspirations never far from the fore, Slim wangled his way into the Birmingham University Officers’ Training Corps in 1912 (even though he was not at the University), and was thus able to be commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment on 22 August 1914.

It was with the Warwicks that, on 8 August 1915, he was badly wounded by a Turkish machine gun while attempting, at the head of his very depleted company, to storm Hill 971 on the Sari Bair Ridge, the long spine that ran along the peninsula and dominated the surrounding countryside running down to the sparkling Aegean. The slopes of the extensive Sari Bair position were of steep, bare, sandy rock, interspersed with patches of scrub thorn. Below the spine a mass of confusing nullahs and ravines undulated wildly, confusing even the most competent subaltern possessed of a map and compass. By the time the Warwicks reached the start point of the brigade attack, the men of 1st Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles, to their right, Slim’s company had been reduced to 50 men and he was its third commander in 48 hours. They were all dog tired. ‘For three nights and two days’ he later wrote, ‘with very little sleep, not much food and less water, we had scrambled, climbed and wandered, often lost, through this jumble of ravines and ridges.’8 Clambering forwards, too tired even to duck to avoid the whistling bullets, he led his men into the teeth of the Turkish defences. He was then hit by machine-gun fire from the ridge to his right, and fell unconscious to the ground. He was lucky to survive, the bullet missing his spine by a fraction. In the four days following the landing of 9th Warwicks in the Dardanelles the battalion suffered 414 casualties. Taken from the battlefield on a bumpy stretcher and evacuated painfully by hospital ship, first to Egypt and then to England, he wrote to a friend from the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, where he spent six months in convalescence, that he had been ‘pipped’ through the lungs by a bullet that ‘smashed the left shoulder to blazes and bust the top of my arm.’9