Table of Contents

Cover

Related Titles

Title page

Copyright page

Preface

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

2 Synthesis Approach of Mesoporous Molecular Sieves

2.1 Synthesis

2.2 Hydrothermal Synthesis

2.3 Removal of Template

2.4 Basic Synthesis

2.5 Acidic Synthesis

2.6 Nonaqueous Syntheses

2.7 Postsynthesis Treatment

2.8 Stability of Mesoporous Materials

2.9 Pore-Size Control

3 Mechanisms for Formation of Mesoporous Materials

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Synthesis Pathways

3.3 Mesophase Tailoring

3.4 Hard-Templating Approach

4 Structural Characterization Methods

4.1 XRD

4.2 Electron Microscopy

4.3 NMR

4.4 Physical Sorption

5 Representative Mesoporous Silica Molecular Sieves

5.1 D Mesostructures

5.2 3D Hexagonal Phases

5.3 Cubic Phases

5.4 Disordered Mesostructures

6 Doping in Mesoporous Molecular Sieves

6.1 Aluminum Doping

6.2 Boron Doping

6.3 Gallium and Indium Doping

6.4 Germanium and Tin Doping

6.5 Transition-Metal Doping

7 Morphology Control

7.1 The Methods and Techniques

7.2 Typical Morphologies

7.3 Magnetically Responsive Ordered Mesoporous Materials

8 Mesoporous Nonsilica Materials

8.1 Mesoporous Carbon

8.2 Mesoporous Polymers

8.3 Mesoporous Nonsiliceous Oxides

8.4 Mesoporous Metals

8.5 Mesoporous Metal Chalcogenides

8.6 Ordered Mesoporous Nonoxide Ceramic Materials

8.7 Mesoporous Metal Nitrides, Carbides and Fluorides

9 Organic Group Functionalized Mesoporous Silicas

9.1 Synthetic Approaches

9.2 Combinatorial Synthesis

9.3 Accessibility to the Active Site and Applications

9.4 Conclusions

10 Applications of Mesoporous Molecular Sieves

10.1 Catalysts and Carriers

10.2 Biology, Separation and Adsorption

10.3 Photoelectric Applications

10.4 High-Tech Fields Such as Electromagnetism

11 Outlook

Index

Related Titles

Bruce, D. W., Walton, R. I., O’Hare, D. (eds.)

Porous Materials

Series: Inorganic Materials Series

2010

ISBN: 978-0-470-99749-9

Su, B.-L., Sanchez, C., Yang, X.-Y. (eds.)

Hierarchically Structured Porous Materials

From Nanoscience to Catalysis, Separation, Optics, Energy, and Life Science

2011

ISBN: 978-3-527-32788-1

Kärger, J., Ruthven, D. M., Theodorou, D. N.

Diffusion in Nanoporous Materials

2012

ISBN: 978-3-527-31024-1

Cejka, J., Corma, A., Zones, S. (eds.)

Zeolites and Catalysis

Synthesis, Reactions and Applications

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32514-6

Sailor, M. J.

Porous Silicon in Practice

Preparation, Characterization and Applications

2011

ISBN: 978-3-527-31378-5

Geckeler, K. E., Nishide, H. (eds.)

Advanced Nanomaterials

2009

ISBN: 978-3-527-31794-3

The Authors

Prof. Dr. Dongyuan Zhao

Fudan University

Department of Chemistry

Handan Road 220

Shanghai 200233

China

Dr. Ying Wan

Shanghai Normal University

Department of Chemistry

Shanghai 200234

China

Dr. Wuzong Zhou

University of St Andrews

School of Chemistry

North Haugh

St Andrews, Fife KY16 9ST

United Kingdom

All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and publisher do not warrant the information contained in these books, including this book, to be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in mind that statements, data, illustrations, procedural details or other items may inadvertently be inaccurate.

Library of Congress Card No.: applied for

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <http://dnb.d-nb.de>.

© 2013 Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany

All rights reserved (including those of translation into other languages). No part of this book may be reproduced in any form – by photoprinting, microfilm, or any other means – nor transmitted or translated into a machine language without written permission from the publishers. Registered names, trademarks, etc. used in this book, even when not specifically marked as such, are not to be considered unprotected by law.

Composition Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong

Cover Design Adam-Design, Weinheim

Print ISBN: 978-3-527-32635-8

ePDF ISBN: 978-3-527-64789-7

ePub ISBN: 978-3-527-64788-0

mobi ISBN: 978-3-527-64787-3

oBook ISBN: 978-3-527-64786-6

Preface

Ordered mesoporous materials, which arose in the early 1990s, are rapidly developing as an interdisciplinary research focus. This kind of material has not only brought a class with a large and uniform pore size (1.5–50 nm), high regularity of nanopores, large surface area and the liquid-crystal template mesostructure, but also put forward the concept in designing periodically arranged organic–inorganic nanoarrays. In the past decades, the related theories, methods and techniques have been explored. As a consequence, novel mesoporous materials are increasingly emerging, and their applications extend from traditional fields, for example, catalysis, adsorption and separation to high-tech fields including chips, biotechnology, optoelectronics, sensors, etc. Workers can therefore obtain a deep insight into the synthesis strategies, pathways and phenomena for the mesoporous molecular sieves, and in particular, establish the relationship for structure–function–synthesis. This book was prepared five years ago in this context.

This book contains 11 chapters. The Introduction (Chapter 1) covers the history of mesoporous materials. From the viewpoint of the synthesis for ordered mesoporous materials, Chapters 2 and 3 summarize the synthetic pathways and the key factors such as the surfactant, hydrothermal method, pH value of media, and post-treatment, to adjust mesostructure and pore size, as well as the corresponding formation mechanism such as the surfactant self-assembly and hard-template nanocasting. Provided that these factors and mechanisms can be fully grasped, researchers, even beginners, can easily obtain high-quality mesoporous materials. Chapter 4 describes the most widely used experimental techniques on the structural characterization of mesoporous materials. In Chapters 5–7, we focus on the mesostructure, functionalization and morphology control of ordered mesoporous materials. The emphasis on mesoporous silicates is due to the fact that silica materials have been extensively and comprehensively investigated. Researchers can clearly understand the history and progress of the ordered mesoporous silica materials. Chapter 8 is devoted to the metal oxide, carbon, polymers, metals, carbides, sulfides and other nonsilica mesoporous materials, and Chapter 9 is devoted to the organic group functionalized mesoporous materials. These functional materials with diversified compositions could certainly play a major role in the field of optics, electricity, magnetism, organic synthesis, etc. In Chapter 10, we deal with the applications of mesoporous materials. It is apparent that the mesoporous material field is eager for more and more researchers from other fields to explore attractive applications. Finally, the latest progress of mesoporous materials are overviewed, and the next stages are put into perspective.

Ordered mesoporous materials have been experiencing a rapid development in the past decade. A comprehensive review is thus necessary. This is the purpose of this book, including the understanding, induction and summary from authors. This book is organized by the guidelines: (i) following the forefront of current research, and striving to reflect the latest progress and developments; (ii) comprehensive review with focus on basic fundamental research; and (iii) practical research experience in methodology, experiment skills, and data analysis. More especially, we put lots of effort on the basic knowledge in ordered mesoporous materials. Therefore, this book is especially readable for beginners and graduate students who have just entered into this field. We hope that they can, through reading this book, fully understand the chemistry of ordered mesoporous materials, grasp synthesis skills, obtain high-quality materials, and therefore, deeply explore the material chemical physics and their applications. Under the guidelines, most of the chapters were written by Professor Dongyuan Zhao at Fudan University and his students, while Chapters 3, 8 and 11 were written by Professor Ying Wan at Shanghai Normal University, Chapter 4 was written by Professor Wuzong Zhou at University of St. Andrews, and some chapters (the fifth and sixth chapters) were done jointly by the three of us. We continuously gained help from other experts in this field and the graduate students in our groups. Professor Yifeng Shi (Hangzhou Normal University, Chapter 10), Dr. Hao Na (Chapter 9), Dr. Renyuan Zhang, PhD candidates Dan Feng, Yin Fang, Jianping Yang, and Yingying Lv, participated in the drafting of some chapters. Professor Haifeng Bao at Hangzhou Normal University and Ms. Wenjun Gao at Shanghai Normal University were dedicated to sorting and editing for publication. Here we express our heartfelt appreciation to them.

This book condenses the authors’ great efforts and contributions. We hope that this book can provide beneficial help and inspiration for those researchers who willingly devote themselves to chemistry and materials science, especially to mesoporous materials, and can provide references and text for undergraduate and graduate students, scientists and researchers who are majoring in chemistry, chemical engineering, physics, materials and biology, as well as those interested in mesoporous materials. Due to the relatively wide areas covered in this book, the numerous contents with connection to complex scientific issues, together with the limited knowledge and ability of the authors, we sincerely appreciate the criticism and comments from the readers.

October 2012

Dongyuan Zhao

Ying Wan

Shanghai, China

Wuzong Zhou

St. Andrews, United Kingdom

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the financial support from NSFC and the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee.

Abbreviations

| AA | atomic absorption |

| AAO | anodic aluminum oxide |

| AEPTMS | 3-[2-(2-aminoethylamino)ethylamino]propyltrimethoxysilane |

| AHPCS | allylhydridopolycarbosilane |

| AMS | anionic-surfactant-templated mesoporous silica |

| AOPs | aluminum organophosphonates |

| AOT | sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate |

| AP | ammonium perchlorate |

| APS | 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane |

| APTES | 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane |

| ATMS | allyltrimethoxysilane |

| BdB | Broekhoff and de Boer |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BJH | Barrett–Joyner–Halanda |

| BTEE | 1,2-bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane |

| ccp | cubic close packing |

| CDBA | cetyldimethylbenzylammonium |

| CFA | cooperative formation mechanism |

| CMC | critical micelle concentration |

| CMD | classical molecular dynamic |

| CMI | Chimie des Matériaux Inorganiques |

| CMK | carbon mesostructures from KIAST |

| CMT | critical micelle temperature |

| COF | covalent organic frameworks |

| CP | cloud point |

| CP/MAS NMR | crosspolarization/magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance |

| CPBr | cetylpyridinium bromide |

| CPSM | colloidal phase separation mechanism |

| CSDAs | costructure-directing agents |

| CTAB | cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| CTACl | cetyltrimethylammonium chloride |

| CTEABr | cetyltriethylammonium bromide |

| CTES | 2-cyanoethyltriethoxysilane |

| CTMACl | cetyltriethylammonium chloride |

| CTMAOH | cetyltriethylammonium hydroxide |

| CVD | chemical vapor deposition |

| CVI | chemical vapor infiltration |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| DA | Dubinin–Astakhov |

| DFT | density functional theory |

| DH | Dolimore–Heal |

| DMAB | dimethylamineborane |

| DME | dimethyl ether |

| DMF | N,N-dimethyl formamide |

| D3R | double three-membered ring |

| D4R | double four-membered ring |

| EDLC | electric double-layer capacitor |

| EDMHEAB | N-eicosane-N,N-dimethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl) ammonium bromide |

| EDIT | evaporation-mediated DIRECT TEMPLATING |

| EDTANa4 | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt |

| EDX | energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| EELS | electron energy-loss spectroscopy |

| EISA | evaporation-induced self-assembly |

| EM | electron microscopy |

| EOA | triethylorthoacetate |

| EPR | electronic paramagnet resonance |

| ESEEM | electron spin-echo envelope modulation |

| ET | electron tomography |

| FA | furfuryl alcohol |

| FDU | FuDan University |

| FFT | fast Fourier transform |

| FITC | fluorescence isothiocyanate |

| FSM | folded sheets mechanism |

| FT | Fourier transform |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| FWHM | full width half-maximum |

| F127 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO106PO70EO106) |

| F108 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO132PO50EO132) |

| F98 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO123PO47EO123) |

| HAADF | high-angle angular dark field |

| hcp | hexagonal close packing |

| HK | Horvath–Kawazoe |

| HMS | hexagonal mesoporous silica |

| HRTEM | high-resolution transmission electron microscopy |

| HTACl | hexadecyltrimethylammonium chloride |

| ICP-AES | inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry |

| IEP | isoelectric point |

| IR | infrared spectroscopy |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Association |

| IZA | International Zeolites Association |

| KIT | Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology |

| L121 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO5PO70EO5) |

| LB | Langmuir–Blodgett |

| LCT | liquid-crystal templating |

| MAB | tri(methylamino)borazine |

| MAO | methylalumoxane |

| MAS-5 | mesoporous aluminosilica molecular sieves |

| MAS NMR | magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance |

| MBG | mesoporous bioactive glass |

| MCF | mesoporous cellular foam |

| MCM | Mobil Company of Matter |

| MIBE | methyl-isobutyl ether |

| MMS | mesoporous molecular sieves |

| MOF | metalorganic framework |

| MPTES | mercaptopropyltriethoxysilane |

| MPTMS | 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane |

| MPs | mesophase pitches |

| MSNs | mesoporous silica nanoparticles |

| MTAB | myristyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| MTES | methyltrimethoxysilane |

| MWD | microwave digestion |

| NIR | near-infrared |

| NLDFT | nonlocal density functional theory |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| ODMS | octyldimethylsilyl |

| OMC | ordered mesoporous carbon |

| OTAC | octadecyltrimethyl ammonium chloride |

| PAA | polyacrylic acid |

| PAN | polyacrylonitrile |

| PANI | polyaniline |

| PBA | poly (butyl acrylate) |

| PB-b-PEO | polybutadiene-block-poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PBMSB-b-PS | polybutenylmethyl silacyclobutane-b-polystyrene |

| PCMS | polycarbomethylsilane |

| PCS | polycarbosilane |

| PCS-b-PMMA | polycarbosilanes-b-polymethylmethacrylate |

| PCS-b-PS | polycarbosilanes-b-polystyrene |

| PDMS | polydimethylsiloxane |

| PEE | poly(ethylethylene) |

| PEG | poly (ethylene glycol) |

| PEO | poly(ethylene oxide), (CH2CH2O)n |

| PEO-PEE | poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(ethyl ethylene) |

| PEO-PEP | poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(ethylene-alt-propylene) |

| PEO-PMMA-PS | poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(methyl methacrylate)-polystyrene |

| PFA | poly(furfuryl alcohol) |

| PI | polyisopropenyl |

| PI-b-PEO | poly(isoprene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PI-b-PDMAEMA | polyisoprene-b-polydimethylaminoethylmethacrylate |

| PI-PS-PEO | poly(isopropenyl)-poly(styrene)-poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PIB-b-PEO | poly(isobutylene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PLA-PDMA-PS | polylactide-polydimethylacrylamide-polystyrene |

| PMA | phosphomolybdic acid |

| PMO(s) | periodic mesoporous organosilica(s) |

| PNB-b-PDB | polynorbornene-b-polynorbornenedecaborane |

| PP | polypropylene |

| PPO | poly(propylene oxide), (CH(CH3)CH2O)n |

| PPQ-PS | poly(phenylquinoline)-block-polystyrene |

| PS-b-PEO | polystyrene-b-poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PS-b-PFEMS | polystyrene-b-polyferrocenylethylmethylsilane |

| PS-PDMA-PLA | polystyrene-polydimethylacrylamide-polyactide |

| PS-PLA | polystyrene-polylactide |

| p-TSA | p-toluenesulfonic acid |

| PTA | phosphotungstic acid |

| PVS | polyvinylsilazane |

| PVSA-b-PS | olypentamethylvinyl cyclodisilazane-b-polystyrene |

| PVSZ-b-PS | poly((vinyl)silazane)-block-poly(styrene) |

| P123 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO20PO70EO20) |

| P2VP-PI | poly(2-vinylpyridine)-polyisopren |

| P4VP-PS | poly(4-vinylpyridine)-polystyrene |

| P65 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO20PO30EO20) |

| P85 | poly(oxyethylene)-b-poly(oxypropylene)-b-poly(oxyethylene), (EO26PO39EO20) |

| SAED | selected-area electron diffraction |

| SAXS | small-angle X-ray scattering |

| SBA | Santa Barbara Airport |

| SC | supercritical |

| SCMS | solid core/mesoporous shell |

| SDA | structure-directing agent |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SF | Saito–Foley |

| STEM | scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| TDA | tetradecylamine |

| TBOT | tetrabutylorthotitanate |

| TEA | triethanolamine |

| TEAH3 | 2,2′,2″-nitrile-triethanol |

| TEAOH | tetraethylammonium hydroxide, (C2H5)4NOH |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy |

| TEOS | tetraethyl orthosilicate |

| TFA | trifluoroacetate |

| TGA | thermogravimmetric analysis |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TMAOH | tetramethylammonium hydroxide, (CH3)4NOH |

| TMAPS | N-trimethoxylsilylpropyl-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride |

| TMB | 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene |

| TMOS | tetramethyl orthosilicate |

| TPD | temperature programmed desorption |

| TUD | Delft University of Technology |

| VH/VL | hydrophilic/hydrophobic ratio |

| VTES | vinyltriethoxysilane |

| VTMS | vinyltrimethoxysilane |

| WAXS | wide-angle X-ray scattering |

| XANES | X-ray near-edge absorption spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

1

Introduction

Materials science is one of the most important subjects of sciences and technologies in the twenty-first century. Its importance has been emphasized by the governments via formulating their national policies in the developed countries, as well as many developing countries. New materials not only greatly promote the developments of industry, agriculture, medicine, environment, aerospace, and information science and so on, but may also demonstrate some revolutionary changes of their forms and novel functions, and thereby bring about tremendous changes to human life. Unlike the traditional materials science dominated by metals and metallurgy, modern materials science has become a typical interdisciplinary field. Any major development of new materials, for example high-temperature superconductors, novel catalysts, many functional nanomaterials, etc., requires collaboration of scientists from many different disciplines.

Porous silicates are a huge family of inorganic materials, possessing open-pore frameworks and large surface area (including the inner and outer surfaces). Based on IUPAC, porous materials according to the pore diameter can be classified into three categories: those with pore diameters less than 2 nm are microporous; pore sizes between 2 and 50 nm are mesoporous; and pore diameters greater than 50 nm are called macroporous materials. “Nano” is a concept with the size from 1 to 100 nm; therefore all the above three kinds of porous materials can be designated as nanoporous materials. However, in most of the literature, nanoporous materials refer to mesoporous or/and microporous materials.

Conventional microporous molecular sieves have a uniform sieve-like pore structure and large surface area. They are excellent adsorbents, catalysts, carriers (catalyst supports), ion-exchange agents and nanoreactors. They have been extensively used in chemical, petrochemical, gas separation industries, and other fields. The vast majority of such materials possess perfect atomic crystal structures, that is, the position of each atom in the unit cell is fixed. For example, in a zeolite A with a cubic (space group  ) structure (unit cell parameter of 11.9 nm) (see Figure 1.1a), 24 of the silicon and aluminum atoms occupy (24 k) lattice sites (atomic coordinates: 0.370, 0.183, 0); and 48 of the oxygen atoms occupy the positions of the (24 m) (0.110, 0.110, 0.345), (12 h) (0, 0.220, 0.5) and (12i) (0.289, 0.289, 0) [1]. Uniform pore arrays in microporous molecular sieves offer good spatial selectivity (shape selectivity) in catalysis. However, the pore sizes of zeolites, microporous molecular sieves are typically less than 1.3 nm, and therefore limit the applications that involve transfer and conversion of macromolecules. Consequently, the creation and development of mesoporous materials have become an important branch in catalysis and inorganic chemistry. In addition, the nanoscale mesopores can be utilized as the hard template for fabricating other nanomaterials, which offer good opportunities in exploring new applications.

) structure (unit cell parameter of 11.9 nm) (see Figure 1.1a), 24 of the silicon and aluminum atoms occupy (24 k) lattice sites (atomic coordinates: 0.370, 0.183, 0); and 48 of the oxygen atoms occupy the positions of the (24 m) (0.110, 0.110, 0.345), (12 h) (0, 0.220, 0.5) and (12i) (0.289, 0.289, 0) [1]. Uniform pore arrays in microporous molecular sieves offer good spatial selectivity (shape selectivity) in catalysis. However, the pore sizes of zeolites, microporous molecular sieves are typically less than 1.3 nm, and therefore limit the applications that involve transfer and conversion of macromolecules. Consequently, the creation and development of mesoporous materials have become an important branch in catalysis and inorganic chemistry. In addition, the nanoscale mesopores can be utilized as the hard template for fabricating other nanomaterials, which offer good opportunities in exploring new applications.

Mesoporous materials with ordered pore arrays became a hot research topic in 1992, when Mobil Oil Corporation (Mobil) scientists first reported the M41S series of mesoporous silica materials [2, 3]. Long-chain cationic surfactants were used as a structure-directing agent to synthesize ordered mesoporous (alumino-) silicate materials. However, this approach was not a brand new method, it was actually demonstrated 20 years earlier. In a patent by French scientists in the early 1970s, a method was recorded to tune the density of silica gels by using long-chain cationic surfactants. Following the synthesis batch mentioned in the patent, workers could easily prepare 2D hexagonal mesoporous silica that is exactly the same as the most famous MCM-41 (Figure 1.1b). However, the patent did not produce enough attention, mainly due to the lack of XRD and electron microscopy characterization data. Japanese scientists, earlier than 1990, also started the synthesis of mesoporous materials. They utilized a cationic surfactant to support a so-called Kanemite layered clay. The clay structure was destroyed in a high-alkalinity solution (high concentration of NaOH). A new mesostructured material was generated, which was later named as FSM-16 mesoporous silica. Once again, attention was not given because the products were mixed phases, no TEM images and XRD patterns were provided. Furthermore, at that time, because of the lack of indepth understanding on formation mechanisms, the concept of “mesoporous” was not realized. On the other hand, Mobil researchers not only developed a family of mesoporous materials with ordered pore arrangements, but also proposed a general “liquid-crystal templating” mechanism with detailed synthesis method. A new inorganic synthetic chemistry research area began to rise.

It has been well known that dealumination can produce mesopores in zeolites. However, both the pore sizes and numbers are very dependent on the dealumination conditions, so that the mesopores are disordered and out of control. Layered materials such as clays and phosphates, can be pillared by large molecules including polycations (such as alumina oligmers Al137+) and silicates, and accordingly mesopores are generated. These materials are so-called pillared clays or pillared molecular sieves. Clays include vermiculites, montmorillonites, and typical phosphates such as zirconium phosphates. Mesoporous pillared clays were considered to be the future catalysts for heavy-oil cracking. Unfortunately, it was later discovered that the drawbacks, including weak surface acidity, easy coke deactivation, and low thermal stability, make them unfeasible for catalytic cracking. In addition, the pillars are amorphous and irregularly arranged despite the ordered atomic crystals of clays and phosphates, which leads to nonuniform mesopore sizes and disordered pore arrangement. Although the aluminosilicate gels with narrow pore-size distribution prepared from a well-controlled sol-gel process can serve as pillars, the disordered pore arrays are maintained and cannot be avoided.

Workers have witnessed a rapid development in ordered mesoporous materials, including the new mesostructures and compositions, the formation mechanisms, and applications [4]. If we refer to SCI expanded system (The Web of Science) and use “mesoporous” as the subject, we can clearly find a predominantly increasing publication numbers (Figure 1.2). This demonstrates the emerging development trends in this field. The establishment of the International Mesostructured Materials Association (IMMA) has promoted the development of mesoporous materials. The theme of the 13th International Zeolite Conference held in July 2001 in Montpellier, France, was “zeolites and mesoporous materials in the dawn of the 21st century”. Mesoporous molecular sieves have since been officially accepted as an important branch of the zeolite materials in IZA.

So far, dozens of mesoporous molecular sieves have been synthesized, most of them have ordered mesostructures and pore arrangements. Since the first series of mesoporous silica materials M41S reported by Mobil Corporation, the most striking materials are explored by the Stucky group from University of California, Santa Barbara, and so-called SBA series. In addition, scientists from various countries, including Japan, Korea, China, Canada, UK, and France have contributed much to the mesoporous families. Among them, the KIT series from a Korea scientist, Prof. Ryoo’s group in KAIST and the FDU series by Prof. Zhao’s group in Fudan University, China have been extensively investigated.

Despite crystalline frameworks as one of the major goals, almost all mesoporous silicates possess amorphous pore-wall structures, which limit their applications in petrochemistry, optoelectronic devices, etc. In terms of the structure, mesoporous materials are “amorphous”, compared to atomic crystals. The general designation of “ordered mesoporous materials” is basically referred to the pore space structure instead of the traditional crystal structures in atomic scale. Workers follow the concept of “crystal”, “space group” to describe the pore structure of mesoporous materials, only because no more appropriate terms are available. Recent studies have revealed that skeletons for some mesoporous materials have fine structures, including micropore distribution, ordered domain boundaries in nanoscale, ordered atomic arrangement in framework by adjusting the compositions, etc. Deep understanding of their microstructures will attract increasing attention.

It is necessary to review the research on mesoporous materials in the past decade. The purpose of this book is a comprehensive review of this field, and together with it, a summary. We hope that this book can be a good reference for researchers, scientists, graduate and undergraduate students in chemistry, chemical engineering, physics, materials, who are interested in mesoporous materials.

References

1 Reed, T.B., and Breck, D.W. (1956) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 78, 5972.

2 Kresge, C.T., Leonowicz, M.E., Roth, W.J., Vartulli, J.C., and Beck, J.S. (1992) Nature, 359, 710.

3 Beck, J.S., Vartulli, J.C., Roth, W.J., Leonowicz, M.E., Kresge, C.T., Schmitt, K.D., Chu, C.T.W., Olson, D.H., Sheppard, E.W., McCullen, S.B., Higgins, J.B., and Schlenker, J.L. (1992) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 114, 10834.

4 Ying, J.Y., Mehnert, C.P., and Wong, M.S. (1999) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 38, 56.

2

Synthesis Approach of Mesoporous Molecular Sieves

2.1 Synthesis

Advances in various fields, such as adsorption, separation, catalysis, hydrogen storage, drug delivery and sensors, require the development of ordered porous materials with high surface areas, controllable structures and systematic tailoring of pore architecture [1]. The structural capabilities at the scale of a few nanometers can meet the demands of the applications emerging in large molecules involved in processes, for example, biology and petroleum productions, therefore, many groups across the world have extensively been focused on the research of mesoporous materials. The synthesis of ordered mesoporous molecular sieves seems easy since the key factors are widely known, such as surfactant template and its concentration, temperature, media, inorganic precursor, etc. However, samples synthesized under “similar conditions” but from different research groups show obviously distinguishing properties, implying that a complicated combination of simple factors will offer great opportunities in creating different porous textures, even novel mesoporous family members. Therefore, fully understanding their roles in the synthesis and formation of mesostructures will obviously benefit the research and further applications.

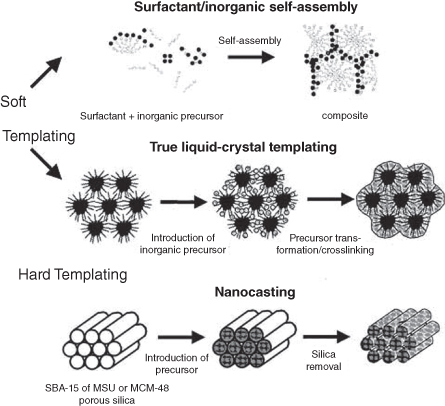

The fabrication of mesoporous materials is mainly concerned with building monodispersed mesosized pore space and arranging them to form a long-range ordered array. Pore-space building is mainly based on the templating synthesis concept, as shown in Figure 2.1 [2]. Two kinds of templating processes are generally used to build mesosized (2–50 nm) pore spaces: supramolecular aggregates such as surfactant formed micelle arrays [3], and preformed mesoporous solids such as mesoporous silica and carbon [4, 5]. The corresponding synthesis routes are commonly described in the literature as soft-templating and hard-templating methods. In the soft-templating method, the ordered pore arrangement is achieved by the cooperative assembly of organic template molecules and guest species that is driven by the spontaneous trend of reducing interface energy [6]. The structure of the organic template molecules is critical for the formation of mesostructure. Therefore, these molecules have also been called structure-directing agents (SDAs). A strong interaction between a SDA and precursor is necessary to avoid the macroscale phase separation. The hard-templating one is also known as the nanocasting method because the entire manufacturing procedure is similar to the traditional casting method invented at least 6000 years ago [5]. The ordered arrangement comes from the preformed ordered mesoporous template such as silicates [7]. Their surface hydrophobic–hydrophilic properties can be easily modified to match specific precursors for efficient filling due to the strong capillarity condensation [4, 8]. This synthesis strategy avoids the control of the cooperative assembly of SDAs and guest species and the sol-gel process of guest species, making it quite successful in numerous materials. Two classes of mesostructures are thus obtained and integrated as components in the mesoporous material family: continuous framework structures with cylindrical or spherical mesopore channels and their reversed replica structure, which can also be regarded as nanowire/nanosphere arrays.

Based on the spatial relationship between the templates and products, the preparation of mesoporous materials can also be classified as “exotemplating” and “endotemplating” methods [9]. For a procedure to prepare the mesoporous materials inside the channels of a porous template, it is called an exotemplating method, while in an endotemplating method, inorganic species are coated outside the template that has been first assembled to an ordered pore shape. The mesoporous materials can be obtained after removing the template.

It has been well known for a long time that dealumination of zeolite molecular sieves can produce some voids at the corresponding occupied aluminum sites that then form the mesopores. However, these mesopores are disordered and randomly distributed. Both the amount and sizes of the mesopores are significantly affected by the complex dealumination conditions, which are uncontrollable [10]. Besides, there are also some other methods to create mesoporous materials. For example, during the procedure to prepare porous Raney nickel catalysts, the mesopores can be acquired by dissolving off the Al with sodium hydroxide from Ni-Al alloy [11]. The pore sizes of aluminosilicate gels can be tuned to have a narrow distribution by strictly controlling the sol-gel synthetic parameters. In addition, by combining the sol-gel chemistry with a phase-separation technique, the disordered and nonuniform mesopores can be made. For instance, it has been reported that to additionally introduce inorganic salts such as sodium chloride, to a normal sol-gel synthesis of zirconium oxide colloids can produce a phase-separated system during cooling. On dissolving the sodium chloride from this mixed system, the mesoporous zirconium oxides can be obtained [12]. However, from all the above methods, the obtained mesoporous materials are not well controlled in both sizes and shapes of mesopores. In particular, all of them are disordered on the pore structures and randomly distributed in size.

For some layered materials such as clays, phosphates and houghites, their layers can be pillared by large-sized inorganic species (called as pillars, such as polymerized cations or alkylorthosilane) to obtain the materials designated as pillared clays or pillared molecular sieves [13]. The aluminum oligomer [Al13O4(OH)24(H2O)12]7+ with a relative large molecular weight is one of the mostly used inorganic pillars. They can insert into the interlayers of the clays through ion exchanges, thus yielding the rectangular mesopores [14]. Clays, either the natural clays such as smectites and montmorillonites, or the artificial layered materials such as phosphates, can be used to yield the mesoporous pillared clays. Of the available phosphates, zirconium phosphate is a typical material for pillaring process [15]. Indeed, in the 1980s, the pillared clays were recognized to be the most promising catalysts in cracking of heavy oil. But later, it was found that the pillared clays have many drawbacks, such as weak surface acidity, low hydrothermal stability, and easy coking, which make them unable to be used in the rigidly required cracking reaction [15, 16]. In addition, although clays and phosphates are crystallized, the pillars are normally amorphous, together with a disordered distribution among the layers. As a result, the mesopores are disordered and have uneven pore-size distribution [15]

Using the hard-templating method to synthesize mesoporous materials, the regularity of mesostructures is largely decided by the ordering of templates and the preparation procedures. The highly ordered mesoporous carbons with replicated structure of the silica template have been successfully prepared by using the nanocasting method [7]. In particular, mesoporous metal oxides can also be prepared with this approach, which actually are difficult to obtain using other methods [17]. It must be emphasized here that although most materials prepared with the above methods possess disordered pore structures, their development clearly made a solid foundation for the discovery of novel ordered mesoporous molecular sieves. Indeed, the idea of the pillared clays directly offered the opportunity to the birth of M41S and FSM-16.

The family of novel ordered mesoporous molecular sieves denoted as M41S was prepared by using the cationic surfactants with long chains that have been utilized for the pillared layers. Before 1990, a Japanese scientist, Prof. Kuroda and his collaborators began the study on intercalation of a natural clay, Kanemite, with cationic surfactants as pillars. They accidentally found that at a concentrated basic media, the structure of Kanemite was destroyed, from which a new type of complex including both surfactant and clays was produced. Indeed, this new material is ordered mesoporous silica, designated as FSM-16 later (see Section 5.1.3) [18, 19]. But in their early reports, they only received the mixed phase of surfactants and silicates. Simultaneously, they gave not enough characterization of the mesostructures and fully understanding of the formation mechanism. In particular, the concept of “mesoporous materials” was not clearly put forward. Therefore, at that time, this work did not arouse researcher’s inspiration about this new type of ordered mesoporous materials. On the other hand, the researchers in the Mobil Company also tried to intercalate the fragments of the layered-structured zeolite MCM-22 with cation surfactants, and finally prepared the pillared molecular sieves MCM-36 [16, 20]. In this work, they found that when tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) was used as pillars, a high basic media (pH > 11) could destroy the layered structures of MCM-22, from which a new type of mesoporous aluminosilicate molecular sieve was thus produced. In 1990, they brought to the public a series of patents about the synthesis of mesoporous aluminosilicates. But as with the Japanese scientists, they just defined the materials as “large-pore-sized molecular sieves” in these patents, while this also did not bring forward the concept of “mesoporous materials”. Then, they began a detailed investigation of these “large-pore-sized molecular sieves”, and found that they have uniform mesopores and the same mesostructures with liquid crystal of surfactants. In particular, they designated them as M41S molecular sieves [1]. Once these results were published in Nature and J. Am. Chem. Soc. (1992), they did arouse a strong response in fields such as materials, chemical engineering, chemistry, petroleum engineering, information engineering, etc.

With these studies, it is found that besides the microporous zeolite molecular sieves, the hydrothermal methods can also be applied to synthesize ordered mesoporous molecular sieves. Different from organic amines or short-chain quaternary ammoniums used in the preparation of microporous molecular sieves, the long-chain alkyl quaternary ammonium surfactants with a positive hydrophilic head group, and a long hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail can be used as a template for mesoporous materials. When dissolved in water, they can aggregate and assemble into supermolecular structures. When the concentration of surfactants is relatively low, micelles can be formed, while at a high surfactant concentration, a liquid-crystal phase is obtained. The interaction of quaternary ammonium surfactant with aluminosilicate oligomers could make them assemble into an ordered array that is highly similar to the formation of liquid-crystals. The mesoporous molecular sieves can be produced after removing the surfactants. The mesostructures are long-range ordered, which makes them show well-resolved diffraction peaks on the small-angle XRD patterns (2θ = 2–10 °). While their inorganic frameworks (inorganic pore walls) are amorphous, presenting a widened diffraction peak on the wide-angle XRD patterns (2θ = 20–25 °), accordingly.

In this preparation, the inorganic silicates (aluminosilicates) can cooperatively assemble with organic cation surfactants through electrostatic interactions (Coulomb force). The surfactants indeed could be regarded as soft templates. The discovery of the new type of mesoporous molecular sieves M41S did produce a shock to the areas of zeolites and materials, which not only brought forth a promising catalyst for transformation of macromolecules and cracking of heavy oils, but also are a breakthrough achievement and show a comparable strong influence with that of molecular sieve ZSM-5, another great achievement by Mobil in the 1970s. Furthermore, with the liquid-crystal phase function of surfactants, the concept of “template” is clearly introduced into the fields of zeolites and materials science for the first time. It is believed that based on the concept of a “template”, a range of new materials with unique properties have been gradually developed since then.

A common thought here is to compare ordered mesoporous silicates with zeolite molecular sieves, both of which have open-pore framework structures. Besides pore size, at least five discrepancies can result from the viewpoints of structure and composition.

1) Structure. Zeolites which are crystalline silicates or aluminosilicates with three-dimensional (3D) framework structures, are perfect inorganic crystals on atomic scale. Mesoporous materials are not crystalline at the atomic scale, and possess a periodic arrangement of a moiety and give well-defined diffraction spots on the mesoscale, which is normally ten times larger than that for atomic crystals.

2) Composition. Classical zeolites are strictly constructed by 3D aluminosilicate tetrahedron (TO4) networks. The pore walls of mesoporous materials are amorphous. Many polyhedra, such as hexa-coordination octahedron (TO6) and penta-coordination trigonal bipyramid (TO5) are allowed to be a subunit. Diverse compositions such as transition-metal oxides [21–24], chalcogenides [25, 26], metals [27], polymers and carbons [28, 29], can then be constituted of mesoporous molecular sieve frameworks (see Chapter 8).

3) Framework. TO4 units constructed by Si and Al atoms in zeolites are generally four-connected by covalent bonds. Only a few zeolites that have surface defects or large rings in their structures possess three connection, like VPI-5 and JDF-20 [30]. The number of surface hydroxyl groups is low. However, not all SiO4 units in mesoporous silicates are four-connected. In other words, a large number of three-connected and even two-connected SiO4 units can be detected that generate the hydrophilic surface with more hydroxyl groups (Si–OH). Besides silicates, transition-metal oxides and other compositions can also construct mesopore frameworks (see Chapter 8).

4) The hydrothermal stability and surface acidity. The mesoporous silicates have lower hydrothermal stability and weaker surface acidity compared with those of zeolite molecular sieves. It is reported that the mesostructure of the mesoporous silica SBA-15 could be well retained after calcination at 1100 °C for 12 h [31–33], comparable with that for zeolites. Despite the high thermal stability, their hydrothermal stabilities are quite different. Generally, mesoporous materials, in particular the mesoporous silica, are not very stable in hot water. For instance, calcined MCM-41 would lose its mesostructural ordering after being treated in boiling water for 6 h [34]. Al-containing MCM-41 is a little more stable in boiling water that pure silica MCM-41 [32, 35]. The mesoporous silica materials (e.g., SBA-15, SBA-11, SBA-12, SBA-14, SBA-16) prepared from nonionic surfactants or amphiphilic triblock-copolymers have a much higher stability whose mesostructures could not be destroyed even after a treatment in boiling water for 10 days [34, 36]. Recently, various methods have been developed, such as adopting the precursors in preparing zeolite molecular sieves as a silica source, through which the stability of mesopore frameworks in boiling water has been significantly improved [37–40]. However, the stability in boiling water cannot be regarded as “true” hydrothermal stability, which indeed refers to the fact that the molecular sieves could maintain their structures after a 100% steam treatment at 600–800 °C. Till now, there are no systematic reports on the “true” hydrothermal stability for mesoporous silica such as MCM-41 and SBA-15. According to some available literature, the mesostructures of silica molecular sieves could collapse after treating them with 100% steam at 800 °C for 4 h [32]. In addition, due to the amorphous framework of mesoporous silicas (aluminosilicates), their surface acidity is relatively weak. On experiencing a high-temperature hydrothermal process, they could completely lose their limited acidity sites on the surface, which is widely recognized to be one of the main reasons preventing them from being applied in the petroleum and chemical engineering industries.

5) Pore walls. Although many efforts have been devoted to the synthesis of mesostructured materials with zeolite-type pore walls [38, 40, 41], there is no major success in reproducibility. Moreover, ordered mesostructures with zeolite nanocrystal walls could not be validated by TEM images. This is mainly due to the fragility of the amorphous silica thin frameworks. An interesting study by Chmelka and coworkers [42] mentioned mesolayered silicas with zeolite-type walls, derived from the hydrothermal treatment of MCM-like starting solution by using D4R or D3R silicates as a precursor. This work implies that the amorphous frameworks inherent to mesoporous silicates are indeed fragile.

Choosing the Gemini surfactants, the one containing both silane coupling agent and a multihead quaternary ammonium salt in its molecule, Ryoo and coworkers [43] successfully prepared the mesoporous zeolite molecular sieves. The long-chain hydrocarbon plays its role in making mesopores, while the small quaternary ammonium salt with a multihead could direct the production of zeolite molecular sieves. But even from this subtle work, the obtained mesopores still have disordered structures. Very recently, they reported the preparation of layered-structured mesoporous zeolite molecular sieve materials. Based on these work, it is believed that we are now not far from obtaining mesoporous silica with crystalline zeolite-type walls.

The hydrothermal method used to synthesize mesoporous silicates by Mobil scientists was similar to that for zeolites. However, the dissimilarity is evident in the preparation of these two kinds of molecular sieves due to their structural differences.

1) Temperature. The synthetic temperature is rather low (from room temperature to 130 °C) for mesoporous silicate molecular sieves [1, 34]. An operational temperature can be as low as −10 °C. The hydrothermal treatment temperature should also be lower than 130 °C (in general, 100–130 °C) even after the precipitation of mesoporous materials, which implies the formation of mesostructures or gels. In contrast, the crystallization temperature for zeolites is much higher, that is, 80–300 °C. The synthesis of mesoporous materials can thus not be considered as a “true” hydrothermal synthesis. A surfactant containing fluorides was used to increase the hydrothermal temperature of mesoporous silicates up to 170 °C [44]. The resultant silicates exhibited high crosslinking degrees, and thus high hydrothermal stability. Unfortunately, the mesostructure regularity was low and the reason was not given by the authors. We believe the hydrothermal temperature was too high to destroy the mesostructures from micelles, resulting in orderless arrays.

2) Formation rate. In comparison with zeolites, mesostructured materials show much faster formation rates. It takes only several seconds to minutes for the crystallization as solid precipitation. The crystallization of zeolites generally requires several days and even months. The faster formation rate results in amorphous and lower crosslinking degree of silicate frameworks.

3) Media. Mesoporous molecular sieves can be formed in nonaqueous media. In many polar organic solvents, like alcohols and tetrahydrofuran (THF), mesostructures can be formed through the solvent EISA or the solvothermal synthesis method [23, 45, 46]. Water is, however, necessary in the preparation of zeolites. Without water, zeolites can not be fully crystallized. A large amount of water must be added in the batch even in the solvothermal method. In contrast to a very wide pH value ranging from 0 to 12 for the synthesis of mesoporous silicates, most zeolites are prepared in basic media. Despite the reduction in the pH values of the synthetic media by the addition of fluoride ions, the successful syntheses of zeolites are carried out only in neutral and weak acidic media [16, 47]. Many expectations are left in the hearts of synthesis scientists, one of which is the preparation of zeolite crystals in acidic media (pH < 2).

4) Morphology. The morphologies of zeolites are strongly related to their structures and are difficult to control because zeolites are a kind of perfect crystals. Although the photonic crystal-like Silicalite-1 [48] has been reported recently, available morphologies of zeolites are still very limited. On the contrary, mesoporous silicates exhibit various morphologies, such as thin films, spheres, monoliths, fibers, etc. [49–52]. This chapter will be mainly focused on the soft-templating approach for the synthesis of ordered mesoporous molecular sieves.

2.2 Hydrothermal Synthesis

Mesoporous silicates are generally prepared under “hydrothermal” conditions. The typical sol-gel process is involved in the “hydrothermal” process. However, the synthetic temperature is relatively low, ranging from room temperature to 150 °C. It can thus not be considered as a “true” hydrothermal synthesis. Mesoporous materials can be synthesized either under basic or acidic conditions. A general procedure includes several steps. First, a homogeneous solution is obtained by dissolving the surfactant(s) in water. Inorganic precursors are then added into the solution where they undergo the hydrolysis catalyzed by an acid or base catalyst and transform to a sol and then a gel. A hydrothermal treatment is then carried out to induce the complete condensation and solidification. The resultant product is cooled to room temperature, filtered, washed and dried. Mesoporous material is finally obtained after the removal of organic template(s) by calcination or extraction.

2.2.1 Surfactant

The selection of surfactants is a key factor. It has been found that the structure and nature of surfactants greatly affect the final mesostructures, pore sizes and surface areas of mesoporous molecular sieves (for details see Chapter 3). Frequently and commercially used surfactants can be classified into cationic, anionic and nonionic surfactants. Until now, few amphoteric surfactants were used in the synthesis [53].

) structure (unit cell parameter of 11.9 nm) (see Figure 1.1a), 24 of the silicon and aluminum atoms occupy (24 k) lattice sites (atomic coordinates: 0.370, 0.183, 0); and 48 of the oxygen atoms occupy the positions of the (24 m) (0.110, 0.110, 0.345), (12 h) (0, 0.220, 0.5) and (12i) (0.289, 0.289, 0) [1]. Uniform pore arrays in microporous molecular sieves offer good spatial selectivity (shape selectivity) in catalysis. However, the pore sizes of zeolites, microporous molecular sieves are typically less than 1.3 nm, and therefore limit the applications that involve transfer and conversion of macromolecules. Consequently, the creation and development of mesoporous materials have become an important branch in catalysis and inorganic chemistry. In addition, the nanoscale mesopores can be utilized as the hard template for fabricating other nanomaterials, which offer good opportunities in exploring new applications.

) structure (unit cell parameter of 11.9 nm) (see Figure 1.1a), 24 of the silicon and aluminum atoms occupy (24 k) lattice sites (atomic coordinates: 0.370, 0.183, 0); and 48 of the oxygen atoms occupy the positions of the (24 m) (0.110, 0.110, 0.345), (12 h) (0, 0.220, 0.5) and (12i) (0.289, 0.289, 0) [1]. Uniform pore arrays in microporous molecular sieves offer good spatial selectivity (shape selectivity) in catalysis. However, the pore sizes of zeolites, microporous molecular sieves are typically less than 1.3 nm, and therefore limit the applications that involve transfer and conversion of macromolecules. Consequently, the creation and development of mesoporous materials have become an important branch in catalysis and inorganic chemistry. In addition, the nanoscale mesopores can be utilized as the hard template for fabricating other nanomaterials, which offer good opportunities in exploring new applications.