Table of Contents

Related Titles

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Abbreviations

Introduction

Part I: Basic Principles and Applications of Photopolymerization Reactions

Chapter 1: Photopolymerization and Photo-Cross-Linking

References

Chapter 2: Light Sources

2.1 Electromagnetic Radiation

2.2 Characteristics of a Light Source

2.3 Conventional and Unconventional Light Sources

References

Chapter 3: Experimental Devices and Examples of Applications

3.1 UV Curing Area: Coatings, Inks, Varnishes, Paints, and Adhesives

3.2 Conventional Printing Plates

3.3 Manufacture of Objects and Composites

3.4 Stereolithography

3.5 Applications in Microelectronics

3.6 Laser Direct Imaging

3.7 Computer-to-Plate Technology

3.8 Holography

3.9 Optics

3.10 Medical Applications

3.11 Fabrication of Nano-Objects through a Two-Photon Absorption Polymerization

3.12 Photopolymerization Using Near-Field Optical Techniques

3.13 Search for New Properties and New End Uses

3.14 Photopolymerization and Nanotechnology

3.15 Search for a Green Chemistry

References

Chapter 4: Photopolymerization Reactions

4.1 Encountered Reactions, Media, and Experimental Conditions

4.2 Typical Characteristics of Selected Photopolymerization Reactions

4.3 Two-Photon Absorption-Induced Polymerization

4.4 Remote Curing: Photopolymerization Without Light

4.5 Photoactivated Hydrosilylation Reactions

References

Chapter 5: Photosensitive Systems

5.1 General Properties

5.2 Absorption of Light by a Molecule

5.3 Jablonski's Diagram

5.4 Kinetics of the Excited State Processes

5.5 Photoinitiator and Photosensitizer

5.6 Absorption of a Photosensitive System

5.7 Initiation Step of a Photoinduced Polymerization

5.8 Reactivity of a Photosensitive System

References

Chapter 6: Approach of the Photochemical and Chemical Reactivity

6.1 Analysis of the Excited-State Processes

6.2 Quantum Mechanical Calculations

6.3 Cleavage Process

6.4 Hydrogen Transfer Processes

6.5 Energy Transfer

6.6 Reactivity of Radicals

References

Chapter 7: Efficiency of a Photopolymerization Reaction

7.1 Kinetic Laws

7.2 Monitoring the Photopolymerization Reaction

7.3 Efficiency versus Reactivity

7.4 Absorption of Light by a Pigment

7.5 Oxygen Inhibition

7.6 Absorption of Light Stabilizers

7.7 Role of the Environment

References

Part II: Radical Photoinitiating Systems

Chapter 8: One-Component Photoinitiating Systems

8.1 Benzoyl-Chromophore-Based Photoinitiators

8.2 Substituted Benzoyl-Chromophore-Based Photoinitiators

8.3 Hydroxy Alkyl Heterocyclic Ketones

8.4 Hydroxy Alkyl Conjugated Ketones

8.5 Benzophenone- and Thioxanthone-Moiety-Based Cleavable Systems

8.6 Benzoyl Phosphine Oxide Derivatives

8.7 Phosphine Oxide Derivatives

8.8 Trichloromethyl Triazines

8.9 Biradical-Generating Ketones

8.10 Peroxides

8.11 Diketones

8.12 Azides and Aromatic Bis-Azides

8.13 Azo Derivatives

8.14 Disulfide Derivatives

8.15 Disilane Derivatives

8.16 Diselenide and Diphenylditelluride Derivatives

8.17 Digermane and Distannane Derivatives

8.18 Carbon–Germanium Cleavable-Bond-Based Derivatives

8.19 Carbon–Silicon and Germanium–Silicon Cleavable–Bond-Based Derivatives

8.20 Silicon Chemistry and Conventional Cleavable Photoinitiators

8.21 Sulfur–Carbon Cleavable-Bond-Based Derivatives

8.22 Sulfur–Silicon Cleavable-Bond-Based Derivatives

8.23 Peresters

8.24 Barton's Ester Derivatives

8.25 Hydroxamic and Thiohydroxamic Acids and Esters

8.26 Organoborates

8.27 Organometallic Compounds

8.28 Metal Salts and Metallic Salt Complexes

8.29 Metal-Releasing Compound

8.30 Cleavable Photoinitiators in Living Polymerization

8.31 Oxyamines

8.32 Cleavable Photoinitiators for Two-Photon Absorption

8.33 Nanoparticle-Formation-Mediated Cleavable Photoinitiators

8.34 Miscellaneous Systems

8.35 Tentatively Explored UV-Light-Cleavable Bonds

References

Chapter 9: Two-Component Photoinitiating Systems

9.1 Ketone-/Hydrogen-Donor-Based Systems

9.2 Dye-Based Systems

9.3 Other Type II Photoinitiating Systems

References

Chapter 10: Multicomponent Photoinitiating Systems

10.1 Generally Encountered Mechanism

10.2 Other Mechanisms

10.3 Type II Photoinitiator/Silane: Search for New Properties

10.4 Miscellaneous Multicomponent Systems

References

Chapter 11: Other Photoinitiating Systems

11.1 Photoinitiator-Free Systems or Self-Initiating Monomers

11.2 Semiconductor Nanoparticles

11.3 Self-Assembled Photoinitiator Monolayers

References

Part III: Nonradical Photoinitiating Systems

Chapter 12: Cationic Photoinitiating Systems

12.1 Diazonium Salts

12.2 Onium Salts

12.3 Organometallic Derivatives

12.4 Onium Salt/Photosensitizer Systems

12.5 Free-Radical-Promoted Cationic Photopolymerization

12.6 Miscellaneous Systems

12.7 Photosensitive Systems for Living Cationic Polymerization

12.8 Photosensitive Systems for Hybrid Cure

References

Chapter 13: Anionic Photoinitiators

13.1 Inorganic Complexes

13.2 Organometallic Complexes

13.3 Cyano Derivative/Amine System

13.4 Photosensitive Systems for Living Anionic Polymerization

References

Chapter 14: Photoacid Generators (PAG) Systems

14.1 Iminosulfonates and Oximesulfonates

14.2 Naphthalimides

14.3 Photoacids and Chemical Amplification

References

Chapter 15: Photobase Generators (PBG) Systems

15.1 Oxime Esters

15.2 Carbamates

15.3 Ammonium Tetraorganyl Borate Salts

15.4 N-Benzylated-Structure-Based Photobases

15.5 Other Miscellaneous Systems

15.6 Photobases and Base Proliferation Processes

References

Part IV: Reactivity of the Photoinitiating System

Chapter 16: Role of the Experimental Conditions in the Performance of a Radical Photoinitiator

16.1 Role of Viscosity

16.2 Role of the Surrounding Atmosphere

16.3 Role of the Light Intensity

References

Chapter 17: Reactivity and Efficiency of Radical Photoinitiators

17.1 Relative Efficiency of Photoinitiators

17.2 Role of the Excited-State Reactivity

17.3 Role of the Medium on the Photoinitiator Reactivity

17.4 Structure/Property Relationships in Photoinitiating Systems

References

Chapter 18: Reactivity of Radicals toward Oxygen, Hydrogen Donors, Monomers, and Additives: Understanding and Discussion

18.1 Alkyl and Related Carbon-Centered Radicals

18.2 Aryl Radicals

18.3 Benzoyl Radicals

18.4 Acrylate and Methacrylate Radicals

18.5 Aminoalkyl Radicals

18.6 Phosphorus-Centered Radicals

18.7 Thiyl Radicals

18.8 Sulfonyl and Sulfonyloxy Radicals

18.9 Silyl Radicals

18.10 Oxyl Radicals

18.11 Peroxyl Radicals

18.12 Aminyl Radicals

18.13 Germyl and Stannyl Radicals

18.14 Boryl Radicals

18.15 Lophyl Radicals

18.16 Iminyl Radicals

18.17 Metal-Centered Radicals

18.18 Propagating Radicals

18.19 Radicals in Controlled Photopolymerization Reactions

18.20 Radicals in Hydrosilylation Reactions

References

Chapter 19: Reactivity of Radicals: Towards the Oxidation Process

19.1 Reactivity of Radicals toward Metal Salts

19.2 Radical/Onium Salt Reactivity in Free-Radical-Promoted Cationic Photopolymerization

References

Conclusion

Index

Related Titles

Ramamurthy, V.

Supramolecular Photochemistry

Controlling Photochemical Processes

2011

ISBN: 978-0-470-23053-4

Allen, N. S. (ed.)

Handbook of Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymeric Materials

2010

ISBN: 978-0-470-13796-3

Albini, A., Fagnoni, M. (eds.)

Handbook of Synthetic Photochemistry

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32391-3

Wardle, B.

Principles and Applications of Photochemistry

2010

ISBN: 978-0-470-01493-6

Stochel, G., Stasicka, Z., Brindell, M., Macyk, W., Szacilowski, K.

Bioinorganic Photochemistry

2009

ISBN: 978-1-4051-6172-5

The Authors

Prof. Jean Pierre Fouassier

formerly University of Haute Alsace

Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Chimie

3 rue Alfred Werner

68093 Mulhouse Cedex

France

Prof. Jacques Lalevée}

University of Haute Alsace

Institut Science des Matériaux

IS2M-LRC 7228, CNRS

15 rue Jean Starcky

68057 Mulhouse Cedex

France

All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and publisher do not warrant the information contained in these books, including this book, to be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in mind that statements, data, illustrations, procedural details or other items may inadvertently be inaccurate.

Library of Congress Card No.: applied for

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <http://dnb.d-nb.de>.

© 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag &Co. KGaA, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany

All rights reserved (including those of translation into other languages). No part of this book may be reproduced in any form – by photoprinting, microfilm, or any other means – nor transmitted or translated into a machine language without written permission from the publishers. Registered names, trademarks, etc. used in this book, even when not specifically marked as such, are not to be considered unprotected by law.

Print ISBN: 978-3-527-33210-6

ePDF ISBN: 978-3-527-64827-6

ePub ISBN: 978-3-527-64826-9

mobi ISBN: 978-3-527-64825-2

oBook ISBN: 978-3-527-64824-5

Dedication

To Geneviève F., Gaëlle, Hugo and Emilie L. for their patience and understanding

To our colleagues over the world for the marvellous time we spent together during all these years.

Abbreviations

| AA | acrylamide |

| ABE | allylbutylether |

| ABP | aminobenzophenone |

| ADD | acridinediones |

| AH | electron/proton donor |

| AIBN | azo bis-isobutyro nitrile |

| ALD | Aldehydes |

| ALK | Alkoxyamines |

| AN | acrylonitrile |

| AOT | bis-2 ethyl hexyl sodium sulfosuccinate |

| APG | alkylphenylglyoxylates |

| AQ | anthraquinone |

| ATR | Attenuated reflectance |

| ATRP | atom transfer radical polymerization |

| BA | butylacrylate |

| BAc | [2-oxo-1,2-di(pheny)ethyl]acetate |

| BAPO | Bis-acyl phosphine oxide |

| BBD | Benzoyl benzodioxolane |

| BBDOM | bisbenzo-[1,3]dioxol-5-yl methanone |

| BC | borane complexes |

| BD | Benzodioxinone |

| BDE | bond dissociation energy |

| BE | benzoin esters |

| BIP-T | bis-(4-tert-butylphenyl) iodonium triflate |

| BMA | butylmethacrylate |

| BME | benzoin methyl ether |

| BMS | benzophenone phenyl sulfide |

| BP | benzophenone |

| BPO | benzoyl peroxide |

| BPSK | 1-Propanone,1-[4-[(4-benzoylphenyl)thio]phenyl]-2-methyl-2-[(4-methylphenyl)sulfonyl] |

| BTTB | 4-Benzoyl(4′-tert-butylperoxycarboxyl) tert-butylperbenzoate |

| BVE | butylvinylether |

| Bz | benzil |

| BZ | benzoin |

| C1 | 7-diethylamino-4-methyl coumarin |

| C6 | 3-(2′-benzothiazoryl)-7-diethylaminocoumarin |

| CA | cyanoacrylates |

| CD | cyclodextrin |

| CIDEP | chemically induced electron polarization |

| CIDNP | chemically induced nuclear polarization |

| CL | caprolactone |

| CNT | photopolymerized lipidic assemblies |

| co-I | co-initiator |

| CPG | cyano N-phenylglycine |

| CQ | camphorquinone |

| CT | charge transfer |

| CTC | charge transfer complex |

| CTP | computer-to-plate |

| CTX | chlorothioxanthone |

| CumOOH | cumene hydroperoxide |

| CW | continuous-wave |

| DB | deoxybenzoin |

| DCPA | dicylopentenyl acrylates |

| DDT | diphenyldithienothiophene |

| DEAP | 2,2-dietoxyacetophenone |

| DEDMSA | N,N-diethyl-1,1-dimethylsilylamine |

| DEEA | 2-(2-ethoxy-ethoxy) ethyl acrylate |

| DFT | density functional theory |

| DH | hydrogen donor |

| DMAEB | dimethylamino ethyl benzoate |

| DMPA | 2,2-dimethoxy -2 phenyl-acetophenone |

| DMPO | 5,5′-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide |

| DPA | diphenyl acetylene |

| dPI | difunctional photoinitiators |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| DTAC | dodecyl trimethylammonium chloride |

| DUV | deep UV |

| DVE | divinylether |

| EA | electronic affinity |

| EAB | diethyl amino benzophenone |

| EDB | ethyl dimethylaminobenzoate |

| EHA | 2-ethyl hexyl ester |

| EL | ethyl linoleate |

| EMP | N-ethoxy-2-methylpyridinium |

| EMS | epoxy-modified silicone |

| Eo | Eosin Y |

| EP | epoxy acrylate |

| EpAc | epoxy acrylate; see Section 16 p359 |

| EPDM | ethylene-propylene-diene monomers |

| EPHT | electron/proton hydrogen transfer |

| EPOX | 3,4-epoxycyclohexane)methyl 3,4-epoxycyclohexylcarboxylate |

| EPT | ethoxylated pentaerythritol tetraacrylate |

| ERL | exposure reciprocity law |

| ESO | epoxidized soybean oil |

| ESR | electron spin resonance |

| ESR-ST | Electron spin resonance spin trapping |

| ET | energy transfer |

| eT | electron transfer |

| EtBz | ethylbenzene |

| EUV | extreme UV |

| EVE | ethylvinylether |

| FBs | fluorescent bulbs |

| Fc(+) | ferrocenium salt derivative |

| FRP | free radical photopolymerization |

| FRPCP | free-radical-promoted cationic polymerization |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| FU | fumarate |

| GRIN | gradient index |

| HABI | 2,2′,4,4′,5,5′-hexaarylbiimidazole |

| HALS | Hindered amine light stabilizer |

| HAP | 2-hydroxy-2- methyl-1- phenyl-1- propanone |

| HCAP | 1-hydroxy- cyclohexyl-1- phenyl ketone |

| HCs | hydrocarbons |

| HDDA | hexane diol diacrylate |

| hfc | hyprefine splitting |

| HFS | hyperfine splitting |

| HOMO | highest occupied molecular orbital |

| HQME | hydroquinone methyl ether |

| HRAM | Highly reactive acrylate monomers |

| HSG | hybrid sol–gel |

| HT | hydrogen transfer |

| IP | ionization potential |

| IPNs | Interpenetrating polymer networks |

| IR | infrared |

| ISC | intersystem crossing |

| ITX | isopropylthioxanthone |

| JAW | julolidine derivative |

| K-ESR | kinetic electron spin resonance |

| KC | ketocoumarin |

| 2K-PUR | two-component polyurethane |

| LAT | light absorbing transients |

| LCAO | linear combination of atomic orbitals |

| LCD | liquid crystal display |

| LDI | Laser direct imaging |

| LDO | limonene dioxide |

| LED | light-emitting diode |

| LFP | laser flash photolysis |

| LIPAC | laser-induced photoacoustic calorimetry |

| LS | light stabilizers |

| LUMO | lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

| MA | methylacrylate |

| MA | monomer acceptor |

| MAL | maleate |

| MB | methylene blue |

| MBI | mercaptobenzimidazole |

| MBO | mercaptobenzoxazole |

| MBT | mercaptobenzothiazole |

| MD | monomer donor |

| MDEA | methyldiethanolamine |

| MDF | medium-density fiber |

| MEK | methyl ethyl ketone |

| MIR | multiple internal reflectance |

| MK | Mischler's ketone |

| MMA | methylmethacrylate |

| MO | molecular orbitals |

| mPI | Multifunctional photoinitiators |

| MPPK | 2-benzyl-2-dimethylamino-1-(4-morpholinophenyl)-1-butanone |

| MWD | molecular weight distribution |

| NAS | 2-[p-(diethyl-amino)styryl]naphtho[1,2-d]thiazole |

| NHC | N-heterocyclic carbene |

| NIOTf | N-(trifluoromethanesulfonyloxy)-1,8-naphthalimide |

| NIR | near-IR reflectance |

| NMP2 | nitroxide-mediated photopolymerization |

| NMP | nitroxide-mediated photopolymerization |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NOR | norbornenes |

| NP | nanoparticles |

| NPG | N-phenyl glycine |

| NQ | naphthoquinone |

| NVET | nonvertical energy transfer |

| NVP | N-vinylpyrolidone |

| OD | optical density |

| OLED | organic light-emitting diode |

| OMC | organometallic compounds |

| On+ | onium salt derivative |

| OrM | organic matrixes |

| P+ | pyrilium salt derivative |

| PAG | Photoacid generators |

| PBG | photobase generator |

| PBN | phenyl-N-tertbutyl nitrone |

| PC | photocatalyst |

| PCBs | printed circuit boards |

| PCL | polycaprolactone |

| PDO | 1-phenyl 2-propanedione-2 (ethoxycarbonyl) oxime |

| PEG | polyethyleneglycol |

| PES | potential energy surface |

| PETA | pentaerythritol tetraacrylate |

| PHS | Poly(hydrosilane)s |

| PHT | pure hydrogen transfer |

| PI | photoinitiator |

| PIS | photoinitiating system |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| PLP | pulsed laser polymerization |

| PLP | Pulsed laser-induced polymerization |

| PMK | 2-methyl-1-(benzoyl)-2-morpholino-propan-1-one |

| PMMA | polymethylmethacrylate |

| POH | phenolic compounds |

| PPD | 1-phenyl-1,2-propanedione |

| PPK | 2-benzyl-2-dimethylamino-1-(phenyl)-1-butanone |

| PS | photosensitizer |

| PS/PI | photosensitizer/photoinitiator |

| PSAs | Pressure-sensitive adhesives |

| PVC | polyvinylchloride |

| PWBs | printed wiring boards |

| PYR | pyrromethene |

| RAFT | reversible addition-fragmentation transfer |

| RB | Rose Bengal |

| RFID | radiofrequency identification |

| ROMP | Ring-opening metathesis photopolymerization |

| ROOH | peroxide derivative |

| ROOH | hydroperoxide derivative |

| ROP | ring-opening polymerization |

| RP | radical pair |

| RPM | radical pair mechanism |

| RSH | mercaptan |

| RT-FTIR | real-time Fourier transform infrared |

| SCM | solvatochromic comparison method |

| SCRP | spin-correlated radical pair |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SG1 | N-(2-methylpropyl)-N-(1-diethylphosphono-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-N-oxyl |

| SHOMO | singly highest occupied molecular orbital |

| SOMO | singly occupied molecular orbital |

| STY | styrene |

| SU | suberone |

| SWNT | single-wall carbon nanotube |

| TEA | triethyl amine |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6, tetramethylpiperidine N-oxyl radical |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| ThP | thiophene |

| TI | titanocene derivative |

| TIPNO | 2,2,5-tri-methyl-4-phenyl-3-azahexane-3-nitroxide |

| TLS | thermal lens spectroscopy |

| TM | triplet mechanism |

| TMP | 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine |

| TMPTA | trimethylolpropane triacrylate |

| TP+ | thiopyrilium salt derivative |

| TPA | two-photon absorption |

| TPGDA | tetrapropyleneglycol diacrylate |

| TPK | 1-[4-(methylthio) phenyl]-ethanone |

| TPMK | 2-methyl-1-(4-methylthiobenzoyl)-2-morpholino-propan-1-one |

| TPO | 2,4,6-trimethyl benzoyl-diphenylphosphine oxide |

| TPP | triphenylphosphine |

| TR-ESR | time resolved electron spin resonance |

| TR-FTIR | time-resolved Fourier transform infra red |

| TR-S2FTIR | Laser-induced step-scan FTIR spectroscopy |

| TS | transition state |

| TST | transition state theory |

| TTMSS | tris(trimethyl)silylsilane |

| TX | thioxanthone |

| TX-SH | 2-mercaptothioxanthone |

| Tz | triazine derivative |

| ULSI | ultra large scale integration |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| UVA | UV absorbers |

| VA | vinyl acetate |

| VC | vinylcarbazole |

| VE | vinyl ethers |

| VE | vinylacetate |

| VET | vertical energy transfer |

| Vi | violanthrone |

| VIE | vitamin E |

| VLSI | very large scale integration |

| VOC | volatile organic compounds |

| VP | vinylpyrrolidone |

| VUV | vacuum ultraviolet |

| XT | xanthones |

Introduction

Light-induced polymerization reactions are largely encountered in many industrial daily life applications or in promising laboratory developments. The basic idea is to readily transform a liquid monomer (or a soft film) into a solid material (or a solid film) on light exposure. The huge sectors of applications, both in traditional and high-tech areas, are found in UV curing (this area corresponds to the largest part of radiation curing that includes UV and electron beam curing), laser imaging, microlithography, stereolithography, microelectronics, optics, holography, medicine, and nanotechnology.

UV curing represents a green technology (environmentally friendly, nearly no release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), room temperature operation, possible use of renewable materials, use of convenient light sources (light-emitting diodes (LEDs), household lamps, LED bulbs, and the sun) that continues its rapid development. The applications concern, for example, the use of varnishes and paints (for a lot of applications on a large variety of substrates, e.g., wood, plastics, metal, and papers), the design of coatings having specific properties (for flooring, packaging, release papers, wood and medium-density fiber (MDF) panels, automotive, pipe lining, and optical fibers), the development of adhesives (laminating, pressure sensitive, and hot melt), and the graphic arts area (drying of inks, inkjets, overprint varnishes, protective and decorative coatings, and the manufacture of conventional printing plates).

Other applications of photopolymerization reactions concern medicine (restorative and preventative denture relining, wound dressing, ophthalmic lenses, glasses, artificial eye lens, and drug microencapsulation), microelectronics (soldering resists, mask repairs, encapsulants, conductive screen inks, metal conductor layers, and photoresists), microlithography (writing of complex relief structures for the manufacture of microcircuits or the patterning of selective areas in microelectronic packaging using the laser direct imaging (LDI) technology; direct writing on a printing plate in the computer-to-plate technology), 3D machining (or three-dimensional photopolymerization or stereolithography) that gives the possibility of making objects for prototyping applications, optics (holographic recording and information storage, computer-generated and embossed holograms, manufacture of optical elements, e.g., diffraction grating, mirrors, lenses, waveguides, array illuminators, and display devices), and structured materials on the nanoscale size.

Photopolymerization reactions are currently encountered in various experimental conditions, for example, in film, gas phase, aerosols, multilayers, (micro)heterogeneous media or solid state, on surface, in ionic liquids, in situ for the manufacture of microfluidic devices, in vivo, and under magnetic field. Very different aspects can be concerned with gradient, template, frontal, controlled, sol–gel, two-photon, laser-induced or spatially controlled, and pulsed laser photopolymerization.

As a photopolymerization reaction involves a photoinitiating system, a polymerizable medium, and a light source, a strong interplay should exist between them. The photoinitiator has a crucial role as it absorbs the light, converts the energy into reactive species (excited states, free radicals, cations, acids, and bases) and starts the reaction. Its reactivity governs the efficiency of the polymerization. A look at the literature shows that a considerable number of works are devoted to the design of photosensitive systems being able to operate in many various (and sometimes exotic) experimental conditions. This research field is particularly rich. Fantastic developments have appeared all along the past three decades. Significant achievements have been made since the early works on photopolymerization in the 1960s and the traditional developments of the UV-curing area. At present, high-tech applications are continuously emerging. Tailor-made photochemistry and chemistry have appeared in this area. The search for a safe and green technology has been launched. Interesting items relate not only to the polymer science and technology field but also to the photochemistry, physical chemistry, and organic chemistry areas.

We believe that the proposed book focused on this exciting topic related to the photosensitive systems encountered in photopolymerization reactions will be helpful for many readers. Why a new book? Indeed, in the past 20 years, many aspects of light-induced polymerization reactions have been obviously already discussed in books and review papers. Each of these books, however, usually covers more deeply selected aspects depending first on the origin (university, industry) and the activity sector of the author (photochemistry, polymer chemistry, and applications) and second on the goals of the book (general presentation of the technology, guide for end users, and academic scope). Our previous general book published more than 15 years ago (1995) and devoted to the three photoinitiation-photopolymerization-photocuring complementary aspects already provided a first account on the photosensitive systems.

For obvious reasons, all these three fascinating aspects that continuously appear in the literature cannot be unfortunately developed now (in 2011) in detail in a single monograph because of the rapid growth of the research. A book that mostly concentrates on the photosensitive systems that are used to initiate the photopolymerization reaction, their adaptation to the light sources, their excited state processes, the reactivity of the generated initiating species (free radicals, acids, and bases), their interaction with the different available monomers, their working out mechanisms, and the approach for a complete understanding of the (photo)chemical reactivity was missing. This prompted us to write the present book. It aims at providing an original and up-to-date presentation of these points together with a discussion of the structure/reactivity/efficiency relationships observed in photoinitiating systems usable in radical, cationic, and anionic photopolymerization as well as in acid and base catalyzed photocrosslinking reactions. We wish to focus on the necessary role of the basic research toward the progress of the applied research through the large part we have devoted to the involved mechanisms. In fact, everybody is aware that there is no real technical future development without a present high-quality scientific research. In our opinion, such an extensive and complete book within this philosophy has never been written before.

Science is changing very fast. During the preparation of a book, any author has the feeling of walking behind the developments that unceasingly appear. It is rather difficult to have the latest photography of the situation by the end of the manuscript; this is also reinforced by the necessary delay to print and deliver the book. Therefore, we decided here to give not only the best up-to-date situation of the subject but also to take time to define a lot of basic principles and concepts, mechanistic reaction schemes, and examples of reactivity/efficiency studies that remain true and are not submitted to a significant aging on a 10-year timescale.

The book is divided into four parts. In Part I, we deliver a general presentation of the basic principles and applications of the involved photopolymerization reactions with a description of the available light sources, the different monomers and the properties of the cured materials, the various aspects and characteristics of the reactions, and the role of the photosensitive systems and the typical examples of applications in different areas. The part especially concerned with the polymer science point of view (as other books have already dealt in detail with this aspect) focuses on general considerations and latest developments and to what is necessary to clearly understand the following parts. Then, we enter into the heart of the book.

In Parts II and III, we give (i) the most exhaustive presentation of the commercially and academically used or potentially interesting photoinitiating systems developed in the literature (photoinitiators, co-initiators, photosensitizers, macrophotoinitiators, multicomponent combinations, and tailor-made compounds for specific properties), (ii) the characteristics of the excited states, and (iii) the involved reaction mechanisms. We provide an overview of all the available systems but we focus our attention on newly developed photoinitiators, recently reported studies, and novel data on previous well-known systems. All this information is provided for radical photopolymerization (Part II) and cationic and anionic photopolymerization and photoacid and photobase catalyzed photocrosslinking (Part III).

In Part IV, we gather and discuss (i) a large set of data, mostly derived from time-resolved laser spectroscopy and electron spin resonance (ESR) experiments, related to both the photoinitiating system excited states and the initiating radicals (e.g., a complete presentation of the experimental and theoretical reactivity of more than 15 kinds of radicals is provided); (ii) the most recent results of quantum mechanical calculations that allow probing of the photophysical/photochemical properties as well as the chemical reactivity of a given photoinitiating system; and (iii) the reactivity in solution, in micelle, in bulk, in film, under air, in low viscosity media, or under low light intensities.

The book also outlines the latest developments and trends for the design of novel molecules. This concerns first the elaboration of smart systems exhibiting well-designed functional properties or/and suitable for processes in the nanotechnology area. A second direction refers to the development of an evergreen (photo)chemistry elaborating, for example, safe, renewable, reworkable, or biocompatible materials. A third trend is related to the use of soft irradiation conditions for particular applications, which requires the design of low oxygen sensitivity compounds under exposure to low-intensity visible light sources, sun, LEDs, laser diodes, or household lamps (e.g., fluorescence or LED bulbs).

When questioning the Chemical Abstract database, many references appear. We have not intended to give here an exhaustive list of references or a survey of the patent literature. We used, however, more than 2000 references. Pioneer works are cited but our present list of references mainly refers to papers dispatched during the past 15 years. The selection of the articles is most of the time a rather hard and sensitive task. We have done our best and beg forgiveness for possible omissions.

This research field has known a fantastic evolution. We would like now to share the real pleasure we had (and still have) in participating and contributing to this area. Writing this book was really a great pleasure. We hope that our readers, R and D researchers, engineers, technicians, University people, and students involved in various scientific or/and technical areas such as photochemistry, polymer chemistry, organic chemistry, radical chemistry, physical chemistry, radiation curing, imaging, physics, optics, medicine, nanotechnology will appreciate this book and enjoy its content.

And now, it is time to dive into the magic of the photoinitiator/photosensitizer world!

Part I

Basic Principles and Applications of Photopolymerization Reactions

In this first part of the book, we give a general presentation of the photopolymerization reactions, the light sources, the experimental devices and the applications, the role of the photosensitive systems, the evaluation of the practical efficiency of a photopolymerizable medium, and the approach of the photochemical and chemical reactivity. As stated in the introduction, the different aspects related to photopolymerization reactions are currently presented and discussed in books (see, e.g., [1–31]) and review papers (see, e.g., [32–96]). As a consequence, some of the above-mentioned topics that have formerly received a deeper analysis are not exhaustively treated here. In that case, we only provide a basic and rather brief description that should allow an easy understanding of the three subsequent parts.

1

Photopolymerization and Photo-Cross-Linking

Everybody knows that a polymerization reaction [97] consists in adding many monomer units M to each other, thereby creating a macromolecule (Eq. (1.1)).

1.1

The initiation step of this reaction corresponds to the decomposition of a molecule (an initiator I) usually obtained through a thermal process (Eq. (1.2)). This produces an initiating species (e.g., a free radical R·) able to attack the first monomer unit. Other units add further to form the macromolecule.

1.2

Instead of a thermal activation of the polymerization, other stimuli such as light, electron beam, X-rays, γ-rays, plasma, microwaves, or even pressure can be used [85]. Among them, the exposure of a resin (monomer/oligomer matrix) to a suitable light appeared as a very convenient way for the initiation step: in that case, the reaction is called a photopolymerization reaction (Eq. (1.3)).

1.3

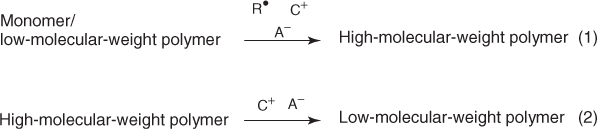

Owing to their absorption properties, monomers or oligomers are usually not sensitive to the available lights (except a few cases involving specifically designed light-absorbing structures). The addition of a photoinitiator (PI) is at least necessary (Eq. (1.4)). Excited states are generated under the light exposure of PI (Chapters 2 and 3). Then, an initiating species is produced. Its nature –radical (R·), cationic (C+), and anionic (A−) –is dependent on the starting molecule.

1.4

Accordingly, the usual types of photopolymerization reactions (radical, cationic, and anionic photopolymerization or acid and base catalyzed photo-cross-linking reactions) can be encountered (Eq. (1.5)) in suitable resins.

1.5

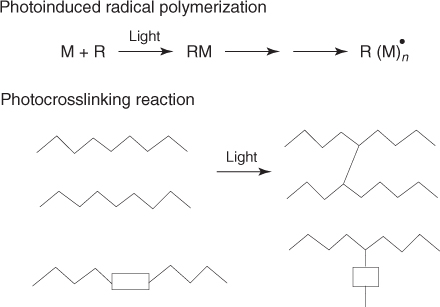

The term photopolymerization is very general and relates to two different concepts (Scheme 1.1). A photoinduced polymerization reaction is a chain reaction where one photon yields one initiating species and induces the incorporation of a large number of monomer units. A photo-cross-linking reaction refers to a process involving a prepolymer or a polymer backbone in which a cross-link is formed between two macromolecular chains. This kind of polymer can be designed in such a way that it contains pendent (e.g., in polyvinylcinnamates) or in-chain photo-cross-linkable moieties (e.g., in chalcone-type chromophore-based polymers).

Scheme 1.1

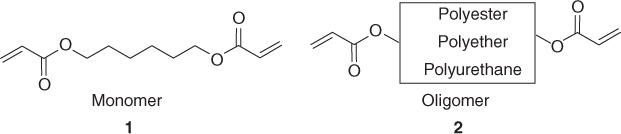

A monomer (1) is a rather small molecule having usually one or several chemical reactive functions (e.g., acrylates), whereas an oligomer (2) is a large molecular structure consisting of repetitive units of a given chemical structure that constitutes the backbone (e.g., a polyurethane) and containing one or more reactive chemical functions. The oligomer skeleton governs the final physical and chemical properties of the cured coating.

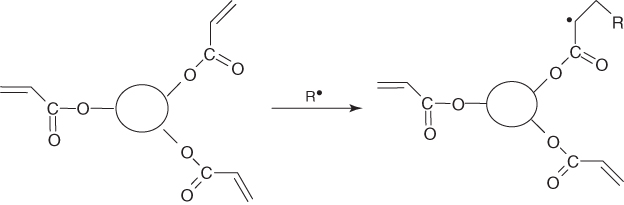

When using multifunctional monomers or oligomers, the photoinduced polymerization reaction does not obviously proceed to form a linear polymer. As it develops in the three directions of space, it also leads to a cross-linking reaction, thereby creating a polymer network (see, e.g., Scheme 1.2 for a free radical reaction). Sometimes, the reaction is depicted as a cross-linking photopolymerization.

Scheme 1.2

A photopolymerizable formulation [25] consists of (i) a monomer/oligomer matrix (the monomer plays the role of a reactive diluent to adjust the viscosity of the formulation; it readily copolymerizes), (ii) a PI or a photoinitiating system (PIS) (containing a PI and other compounds), and (iii) various additives, for example, flow, slip, mist, wetting, dispersion agents, inhibitors for handling and fillers, plasticizers, matting or gloss agents, pigments, and light stabilizers according to the applications.

UV curing is a word that defines an ever-expanding industrial field [6, 10, 16, 25] where the light, often delivered by a mercury lamp, is used to transform a liquid photosensitive formulation into an insoluble solid film for coating applications through a photopolymerization reaction. Photocuring is a practical word that refers to the use of light to induce this rapid conversion of the resin to a cured and dried solid film. Film thicknesses typically range from a few micrometers to a few hundred micrometers depending on the applications. In photostereolithography, the idea consists in building up a solid object through a layer-by-layer photopolymerization procedure.

In the imaging area, an image is obtained according to a process largely described in the literature [8, 9, 17, 90]. The resin layer is irradiated through a mask. A reaction takes place in the irradiated areas. Two basically different reactions can occur: (i) a photopolymerization or a photo-cross-linking reaction that renders the film insoluble (using a suitable solvent allows to dissolve the monomer present in the shadow areas; after etching of the unprotected surface and a bake out of the polymerized film, a negative image is thus formed) and (ii) a depolymerization or a hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity change (that leads to a solubilization of the illuminated areas, thereby forming a positive image). Free radical photopolymerization and photo-cross-linking (Scheme 1.3) lead to a negative image through (i). The acid or base catalyzed reaction (Scheme 1.3) leads either to a negative image (i) or a positive image (ii).

Scheme 1.3

In microelectronics, such a monomer/oligomer or polymer matrix sensitive to a light source is named a photoresist. In imaging technology, the organic matrix is called a photopolymer. Strictly speaking, photopolymer refers to a polymer sensitive to light but this word is often used to design a monomer/oligomer matrix that polymerizes under light exposure. The new term photomaterial refers to an organic photosensitive matrix that leads, on irradiation, to a polymer material exhibiting specific properties useful in the nanotechnology field; it could also design the final material formed through this photochemical route.

References

1. Roffey, C.G. (1982) Photopolymerization of Surface Coatings, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

2. Rabek, J.F. (1987) Mechanisms of Photophysical and Photochemical Reactions in Polymer: Theory and Practical Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, New York.

3. Hoyle, C.E. and Kinstle, J.F. (eds) (1990) Radiation Curing of Polymeric Materials, ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 417, American Chemical Society.

4. Fouassier, J.P. and Rabek, J.F. (eds) (1990) Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology: Applications, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

5. Bottcher, H. (1991) Technical Applications of Photochemistry, Deutscher Verlag fur Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig.

6. Pappas, S.P. (1986) UV-Curing: Science and Technology, Technology Marketing Corporation, Stamford, CT; Plenum Press, New York (1992).

7. Fouassier, J.P. and Rabek, J.F. (eds) (1993) Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, Chapman & Hall, London.

8. Krongauz, V. and Trifunac, A. (eds) (1994) Photoresponsive Polymers, Chapman & Hall, New York.

9. Reiser, A. (1989) Photoreactive Polymers: The Science and Technology of Resists, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

10. Fouassier, J.P. (1995) Photoinitiation, Photopolymerization, Photocuring, Hanser, Münich.

11. Allen, N.S., Edge, M., Bellobono, I.R., and Selli, E. (eds) (1995) Current Trends in Polymer Photochemistry, Ellis Horwood, New York.

12. Scranton, A.B., Bowman, A., and Peiffer, R.W. (eds) (1997) Photopolymerization: Fundamentals and Applications, ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 673, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

13. Olldring, K. and Holman R. (eds) (1997) Chemistry and Technology of UV and EB Formulation for Coatings Inks and Paints, vol. I - VIII, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Sita Technology Ltd, London.

14. Fouassier, J.P. (1998) Photoinitiated Polymerization: Theory and Applications, Rapra Review Reports, Vol. 9(4), Rapra Technology Ltd, Shawbury.

15. Holman, R. (ed.) (1999) UV and EB Chemistry, Sita Technology Ltd, London.

16. Davidson, S. (1999) Exploring the Science, Technology and Application of UV and EB Curing, Sita Technology Ltd, London.

17. Neckers, D.C. (1999) UV and EB at the Millennium, Sita Technology Ltd, London.

18. Fouassier, J.P. (ed.) (1999) Photosensitive Systems for Photopolymerization Reactions, Trends in Photochemistry and Photobiology, Vol. 5, Research Trends, Trivandrum.

19. Crivello, J.V. and Dietliker, K. (1999) Photoinitiators for Free Radical, Cationic and Anionic Photopolymerization, Surface Coatings Technology Series, vol. III (ed. G. Bradley), John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

20. Fouassier, J.P. (2001) Light Induced Polymerization Reactions, Trends in Photochemistry and Photobiology, Vol. 7, Research Trends, Trivandrum.

21. Dietliker, K. (2002) A Compilation of Photoinitiators Commercially Available for UV Today, Sita Technology Ltd, London.

22. Drobny, J.G. (2003 and 2010) Radiation Technology for Polymers, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

23. Belfied, K.D. and Crivello, J.V. (eds) (2003) Photoinitiated Polymerization, ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 847, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

24. Fouassier, J.P. (ed.) (2006) Photochemistry and UV Curing, Research Signpost, Trivandrum.

25. Schwalm, R. (2007) UV Coatings: Basics, Recent Developments and New Applications, Elsevier, Oxford.

26. Schnabel, W. (2007) Polymer and Light, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim.

27. Lackner, M. (ed.) (2008) Lasers in Chemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim.

28. Mishra, M.K. and Yagci, Y. (eds) (2009) Handbook of Vinyl Polymers, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

29. Allen, N.S. (ed.) (2010) Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

30. Fouassier, J.P. and Allonas, X. (eds) (2010) Basics of Photopolymerization Reactions, Research Signpost, Trivandrum.

31. Green, W.A. (2010) Industrial Photoinitiators, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

32. Fouassier, J.P. (2000) Recent Res. Devel. Photochem. Photobiol., 4, 51–74.

33. Fouassier, J.P. (2000) Recent Res. Devel. Polym. Sci., 4, 131–145.

34. Fouassier, J.P. (1999) Curr. Trends Polym. Sci., 4, 163–184.

35. Fouassier, J.P. (1990) Prog. Org. Coat., 18, 227–250.

36. Paczkowski, J. and Neckers, D.C. (2001) Electron Trans. Chem., 5, 516–585.

37. Schnabel, W. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. II (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 95–143.

38. Urano, T. (2003) J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol., 16, 129–156.

39. Fouassier, J.P., Allonas, X., and Burget, D. (2003) Prog. Org. Coat., 47, 16–36.

40. Fouassier, J.P., Ruhlmann, D., Graff, B., Morlet-Savary, F., and Wieder, F. (1995) Prog. Org. Coat., 25, 235–271.

41. Fouassier, J.P., Ruhlmann, D., Graff, B., and Wieder, F. (1995) Prog. Org. Coat., 25, 169–202.

42. Fouassier, J.P. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 1 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 49–118.

43. Fouassier, J.P. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 1–62.

44. Lissi, E.A. and Encinas, M.V. (1991) in Photochemistry and Photophysics, vol. IV (ed. J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 221–293.

45. Fouassier, J.P. (1990) in Photochemistry and Photophysics, vol. II (ed. J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 1–26.

46. Timpe, H.J. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (ed. J.P. Fouassier), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 529–554.

47. Cunningham, A.F. and Desobry, V. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 323–374.

48. Green, W.A. and Timms, A.W. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 375–434.

49. Carlini, C. and Angiolini, L. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 283–322.

50. Li Bassi, G. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 239–282.

51. Murai, H. and Hayashi, H. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 63–154.

52. Steiner, U.E. and Wolff, H.J. (1991) in Photochemistry and Photophysics, vol. IV (ed. J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 1–130.

53. Hayashi, H. (1990) in Photochemistry and Photophysics, vol. I (ed. J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 59–136.

54. Fouassier, J.P. and Lougnot, D.J. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. II (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 145–168.

55. Jacobine, A. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 219–268.

56. Peeters, S. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 177–218.

57. Broer, D.J. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 383–444.

58. Higashi, M. and Niwa, M. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 367–382.

59. Hasegawa, M., Hashimoto, Y., and Chung, C.M. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 341–366.

60. Dworjanyn, P.A. and Garnett, J.L. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 1 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 263–328.

61. Dreeskamp, H. and Palm, W.U. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. II (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 47–56.

62. Mc Lauchlan, K.A. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. I (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 259–304.

63. Phillips, D. and Rumbles, G. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. I (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 91–146.

64. Mc Gimpsey, W.G. (1990) in Lasers in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. II (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 77–94.

65. Bortolus, P. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 603–636.

66. Timpe, H.J., Jockush, S., and Korner, K. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (ed. J.P. Fouassier), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 575–602.

67. Crivello, J.V. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 435–472.

68. Hacker, N.P. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 473–504.

69. Sahyun, M.R., De Voe, R.J., and Olofson, P.M. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 2 (ed. J.P. Fouassier), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 505–529.

70. Davidson, R.S. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 153–176.

71. Decker, C. and Fouassier, J.P. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 1–36.

72. Castle, P.M. and Sadhir, R.K. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 37–72.

73. Cabrera, M., Jezequel, J.Y., and André, J.C. (1993) in Radiation Curing in Polymer Science and Technology, vol. 3 (eds J.P. Fouassier and J.F. Rabek), Elsevier, Barking, pp. 73–97.

74. Allen, N.S. (2005) Photochemistry, vol. 35, The Royal Society of Chemistry, London, pp. 206–271.

75. Decker, C. (1999) in Macromolecules, vol. 143 (ed. K.P. Ghiggino), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weiheim, pp. 45–63.

76. Decker, C. and Hoang Ngoc, T. (1998) in Functional Polymers, Modern Synthetic Methods and Novel Structures, ACS Symposium Series (eds A.O. Patil, D.N. Schultz, and B.M. Novak), American Chemical Society, pp. 286–302.

77. Decker, C. (1998) Des. Monom. Polym., 1, 47–64.

78. Decker, C. and Elzaouk, B. (1997) in Current Trends in Polymer Photochemistry (eds N.S. Allen, M. Edge, I. Bellobono, and E. Selli), Ellis Horwood, New York, pp. 131–148.

79. Decker, C. (1997) in Materials Science and Technology, vol. 18 (ed. H.E.H. Meijer), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, pp. 615–657.

80. Decker, C. (1996) in Polymeric Materials Encyclopedia, vol. 7 (ed. J.C. Salamone), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 5181–5190.

81. Decker, C. (2001) in Specialty Polymer Additives (eds S. Al Malaika, A. Golovoy, and C.A. Wilkic), Backwell Science, Oxford, pp. 139–154.

82. Decker, C. (2003) in Photoinitiated Polymerization, ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 847, Chapter 23 (eds K.D. Belfield and J. Crivello), American Chemical Society, p. 266.

83. Sipani, V. and Scranton, A.B. (2004) in Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology (ed. H.F. Mark), Wiley-Interscience, New York. doi: 10.1002/0471440264.pst491

84. Cai, Y. and Jessop, J.L.P. (2004) in Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology (ed. H.F. Mark), Wiley-Interscience, New York. doi: 10.1002/0471440264.pst490

85. Fouassier, J.P., Allonas, X., and Lalevée, J. (2007) in Macromolecular Engineering: from Precise Macromolecular Synthesis to Macroscopic Materials Properties and Applications, vol. 1 (eds K. Matyjaszewski, Y. Gnanou, and L. Leibler), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, pp. 643–672.

86. Allonas, X., Crouxte-Barghorn, C., Fouassier, J.P., Lalevée, J., Malval, J.P., and Morlet-Savary, F. (2008) in Lasers in Chemistry, vol. 2 (ed. M. Lackner), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, pp. 1001–1027.

87. Arsu, N., Reetz, I., Yagci, Y., and Mishra, M.K. (2008) in Handbook of Vinyl Polymers (eds M.K. Mishra and Y. Yagci), CRC Press, pp. 50–75.

88. Fouassier, J.P., Allonas, X., Lalevée, J., and Dietlin, C. (2010) in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials (ed. N.S. Allen), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, pp. 351–420.

89. Kahveci, M.U., Gilmaz, A.G., and Yagci, Y. (2010) in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials (ed. N.S. Allen), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, pp. 421–478.

90. Ivan, M.G. and Scaiano, J.C. (2010) in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials (ed. N.S. Allen), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, pp. 479–508.

91. Muftuogli, A.E., Tasdelen, M.A., and Yagci, Y. (2010) in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials (ed. N.S. Allen), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, pp. 509–540.

92. Gisjman, P. (2010) in Photochemistry and Photophysics of Polymer Materials (ed. N.S. Allen), John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken, NJ, pp. 627–680.

93. Lalevée, J., El Roz, M., Allonas, X., and Fouassier, J.P. (2009) in Organosilanes: Properties, Performance and Applications, Chapter 6 (eds E. Wyman and M.C. Skief), Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY, pp. 164–193.

94. Lalevée, J., Tehfe, M.A., Allonas, X., and Fouassier, J.P. (2010) in Polymer Initiators, Chapter 8 (ed. W.J. Ackrine), Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY, pp. 203–247.

95. Yagci, Y. and Retz, I. (1998) Prog. Polym. Sci., 23, 1485–1538.

96. Lalevée, J. and Fouassier, J.P. (2011) Polym. Chem., 2, 1107–1113.

97. Matyjaszewski, K., Gnanou, Y., and Leibler, L. (eds) (2007) Macromolecular Engineering: From Precise Macromolecular Synthesis to Macroscopic Materials Properties and Applications, vol. 1, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, pp. 643–672.

2

Light Sources

An electromagnetic radiation, usually referred to as a light, is characterized by a frequency ν (in Hz) or a wavelength λ (in m), which are inversely proportional to one another (Eq. (2.1) where c = ∼ 3 × 108 m s−1 is the speed of light in vacuum); ν is proportional to the wave number ϖ. In photochemistry, λ is very often used in nanometers (nm).

2.1