Contents

Preface to Eighth Edition

Preface to First Edition

Nomenclature and Acronyms

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

About the Contributors

Introduction

Chapter 1 The Discipline of Cost Planning

1.1 Buildings cost money …

1.2 What happened to the cost plan?

1.3 The cost planning process

1.4 Cost planning and the role of the quantity surveyor (QS)

1.5 Public sector building procurement

1.6 International dimensions

1.7 The future of cost planning

Chapter 2 Research and Development in Cost Planning Practice

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Knowledge management in construction

2.3 E-procurement and the cost planning function

2.4 Harnessing digital communication through the supply chain

2.5 Typical applications used in e-procurement and cost planning

2.6 E-procurement and IT developments in cost planning/quantity surveying practice

2.7 Research in cost planning and cost modelling

Chapter 3 The Three Stages of Cost Planning

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Stage 1: The outline client brief, procurement strategy and budget

3.3 Stage 2: The cost planning and control of the design process

3.4 Stage 3: Cost control of the procurement and construction stages

3.5 The role of the cost planner

3.6 Cost planning practice

3.7 Key points

Phase 1 Cost Planning at the Briefing Stage

Chapter 4 Developers’ Motivations and Needs

4.1 Developers and development

4.2 Profit development, social development and user development

4.3 Cost targets for profit development

4.4 Cost targets for social or public sector user development

4.5 Cost targets for private user development

4.6 Cost targets for mixed development

4.7 Cost–benefit analysis (CBA)

4.8 The client’s needs

4.9 Key points

Chapter 5 Client Identification and the Briefing Process

5.1 Introduction

5.2 The client

5.3 Type and level of management service required by a client

5.4 Types of clients – user clients and paying clients and the stakeholder perspective

5.5 The brief and the process of briefing

5.6 Format and content of the brief

5.7 The client’s budget

5.8 Calculating building costs

5.9 Budgetary examples

5.10 Key points

Chapter 6 The Economics of Cost Planning

6.1 The time value of money

6.2 Interest – the cost of finance

6.3 Is interest always taken into account?

6.4 The importance of understanding the cost–time relationship

6.5 The application of simple development economics in cost planning: terminology and nomenclature

6.6 Project cash flow

6.7 Discounted cash flow techniques

6.8 Key points

Chapter 7 Whole Life-cycle Costing and Design Sustainability

7.1 Introduction

7.2 History of WLCC

7.3 Definitions and disambiguation

7.4 Applications of WLCC – the public sector perspective

7.5 WLCC beyond construction

7.6 Private sector procurement

7.7 Theory and methodology

7.8 Disadvantages of whole life costs assessment

7.9 Software tools for WLCC

7.10 Key points

Chapter 8 Procurement and the Relationship with Project Costs

8.1 Introduction

8.2 The traditional procurement system and cost planning

8.3 Standard forms of building contract

8.4 Basic forms of building contract in the traditional method of procurement

8.5 JCT contracts for traditional procurement

8.6 Design and build procurement

8.7 Management-based procurement

8.8 Partnering

8.9 Public sector construction procurement and the Private Finance Initiative

8.10 Key points

Phase 2 Cost Planning at the Design Stage

Chapter 9 The Design Process and the Project Life-cycle

9.1 Introduction

9.2 The building design process

9.3 The design team

9.4 The RIBA Plan of Work

9.5 Comparison of design method and scientific method

9.6 A conceptual design model

9.7 Design techniques

9.8 Generally

9.9 Recognition of design methods in cost information systems

9.10 An evaluative system

9.11 A strategic cost information system

9.12 Key points

Chapter 10 Standard Methods of Cost Modelling

10.1 Prototypes

10.2 Other types of model

10.3 Objectives of modelling

10.4 Traditionalcostmodels

10.5 Horses for courses

10.6 The pyramid

10.7 Single price rate methods

10.8 Elements

10.9 Features

10.10 Standard Method of Measurement (SMM7) – the BQs as a cost model

10.11 Operations and resources

10.12 Spatial costing

10.13 Synthesis

10.14 Design-based building cost models

10.15 The bill of quantities

10.16 Elemental cost analysis

10.17 The Standard Form of Cost Analysis (SFCA)

10.18 Design cost parameters

10.19 Building shape

10.20 Height

10.21 Optimum envelope area

10.22 Further cost modelling techniques

10.23 Classification of models

10.24 Key points

Chapter 11 Cost and Performance Data

11.1 Introduction

11.2 The ambiguous problem of software

11.3 Types and origins of cost data

11.4 The reliability of cost data

11.5 Occupation costs

11.6 Problems with site feedback

11.7 Problems with the analysis of BQs

11.8 Variation in pricing methods

11.9 Variation in BQ rates for different jobs

11.10 Research into variability

11.11 The contractor’s bid

11.12 The structuring of cost data

11.13 An integrated system of groupings?

11.14 Sources of data

11.15 Published cost data

11.16 Future development

11.17 Key points

Chapter 12 Construction Cost Indices

12.1 The cost index

12.2 Use of index numbers

12.3 Approaches to constructing an index

12.4 The factor cost index

12.5 The tender-based index

12.6 Published forms

12.7 Problems in constructing and using cost indices

12.8 Which type of index to use

12.9 Key points

Chapter 13 Cost Planning the Brief

13.1 The brief

13.2 An iterative process

13.3 Preliminary estimate based on floor area

13.4 An example of a preliminary estimate

13.5 An example using BCIS data

13.6 Cost reductions

13.7 Data sources

13.8 Mode of working

13.9 Key points

Chapter 14 Cost Planning at the Scheme Design Stage

14.1 Elemental estimates

14.2 A typical elemental rate calculation

14.3 Examination of alternatives

14.4 Need for care

14.5 The cost plan

14.6 Specification information in the cost plan

14.7 Elemental cost studies

14.8 Foundations

14.9 Frame

14.10 Staircases

14.11 Upper floors

14.12 Roofs

14.13 Rooflights

14.14 External walls

14.15 Internal walls and partitions

14.16 Windows

14.17 Doors

14.18 Floor, wall and ceiling finishes and decorations

14.19 Engineering services

14.20 Joinery fittings

14.21 Cost studies generally

14.22 Preparation of the cost plan

14.23 Method of relating elemental costs in proposed project to analysed example

14.24 Presentation of the cost plan

14.25 Key points

Phase 3 Cost Planning and Control at Production and Operation

Chapter 15 Planning and Managing Project Resources and Costs

15.1 Introduction

15.2 Nature of the construction industry

15.3 Problems of changes in demand

15.4 Costs and prices

15.5 The contractor’s own costs

15.6 Two typical examples

15.7 Cash flow and the building contractor

15.8 Allocation of resource costs to building work

15.9 System building, modular assembly, prefabrication and cost

15.10 Key points

Chapter 16 Resource-based Cost Models

16.1 Effect of job organisation on costs

16.2 A well-managed construction project

16.3 Traditional versus resource-based methods of cost planning

16.4 Value added tax (VAT)

16.5 Resource-based cost models

16.6 Resource programming techniques

16.7 The Gantt chart

16.8 The critical path diagram (or the network diagram)

16.9 Resource levelling (or smoothing)

16.10 Resource-based techniques in relation to design cost planning

16.11 Obtaining resource cost data for building work

16.12 Identification of differing variable costs

16.13 Costing by operations

16.14 Use of resource-based cost information for design cost planning

16.15 Key points

Chapter 17 Cost Control (1): Final Design and Production Drawing Stage

17.1 Cost checks on working drawings

17.2 Carrying out the cost check

17.3 Use of an integrated computer package at production drawing stage

17.4 Use of resource-based techniques at production drawing stage

17.5 Cost reconciliation

17.6 Completion of working drawings and contract documentation

17.7 A critical assessment of elemental cost planning procedures

17.8 Key points

Chapter 18 Cost Control (2): Real Time

18.1 Why real-time cost control?

18.2 The problem of information

18.3 Real-time cost control of lump sum contracts based on BQs

18.4 Real-time cost control of negotiated contracts

18.5 Real-time cost control of cost reimbursement contracts

18.6 Real-time cost control of management contracts

18.7 A spreadsheet cost report on a management contract

18.8 Control of cash flow

18.9 Cash flow control of major development schemes

18.10 Control of short-term cash flow

18.11 Payment delays on profit projects will be to the client’s advantage

18.12 Cost control on a resource basis

18.13 Key points

Chapter 19 Cost Planning of Renovation and Maintenance Work

19.1 Introduction

19.2 The appropriateness of lump sum competitive tenders

19.3 Elemental cost planning inappropriate

19.4 Conflict of objectives

19.5 Risk and uncertainty

19.6 Safety

19.7 Occupation and/or relocation costs

19.8 The need for effective liaison and oversight

19.9 Costs excluding occupation

19.10 Key points

Appendix A: BCIS Elemental Cost Analysis

1 SUBSTRUCTURE

2 SUPERSTRUCTURE

3 FINISHES

4 FITTINGS AND FURNISHINGS

5 SERVICES

6 EXTERNAL WORKS

7 PRELIMINARIES

8 EMPLOYER’S CONTINGENCIES

9 DESIGN FEES (on Design and Build Schemes)

Appendix B: Discount Rate Tables

Index

A portion of the author’s annual royalty payment from sales of this textbook will be donated to the Wakefield and District Branch of the Multiple Sclerosis Society. The branch provides support for families affected by this devastating condition.

© 1964, 1970, 1972, 1984, 1991, 1999, 2007 by the estate of Douglas J. Ferry, 1980, 1984, 1991,

1999, 2007 by Peter Brandon, 1999, 2007 by Jonathan D. Ferry and 2007 by Richard Kirkham

Blackwell Publishing editorial offices:

Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1865 776868

Blackwell Publishing Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

Tel: +1 781 388 8250

Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

Tel: +61 (0)3 8359 1011

The right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted

by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names

and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their

respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the

subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering

professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a

competent professional should be sought.

First published in Great Britain by Crosby Lockwood & Sons Ltd 1964; Second edition (metric)

published 1970; Third edition published 1972; Fourth edition published by Granada Publishing 1980;

Fifth edition published 1984; Sixth Edition published by BSP Professional Books 1991; Seventh Edition

published by Blackwell Science Ltd 1999; Eighth edition published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2007

ISBN: 978-1-4051-3070-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirkham, Richard J.

Ferry and Brandon’s cost planning of buildings/Richard Kirkham. — 8th ed.

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: Cost planning of buildings/Douglas J. Ferry, Peter S. Brandon, Jonathan D. Ferry. 7th ed. 1999.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3070-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4051-3070-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Building–Estimates. 2. Building–Cost control

I. Brandon, P. S. (Peter S.) II. Ferry, Douglas J. (Douglas John) Cost planning of buildings. III. Title.

IV. Title: Cost planning of buildings.

TH435.F36 2007

692—dc22

2007000571

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy,

and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free

practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met acceptable

environmental accreditation standards.

For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website:

www.blackwellpublishing.com/construction

Preface to the Eighth Edition

As an undergraduate student at Liverpool University in the early 1990s, I fondly remember hunting down Ferry and Brandon’s text in the dark, narrow corridors of the Harold Cohen Library. I would often use this text to get to grips with the business of estimating, tendering and taking off. I now consider it a great privilege to have been asked to revise and update the eighth edition. Books don’t last eight editions simply by chance; the ones that do are always very good ones.

The dilemma for any author updating a long-established textbook is ‘how much ought I to change?’ I considered a radical approach to the new edition, but on reflection I questioned the wisdom of this and ultimately formed the opinion that the core structure of the book ought not to be changed, as clearly it worked. This edition is therefore still strongly based around the three-phase process advocated by Ferry and Brandon. The layout has been changed slightly to reflect the major changes that have occurred since the seventh edition, not only within the discipline of cost planning, but also the construction industry generally. For example, the treatment of procurement is prominent at the start of the text rather than towards the end. I have also recognised the ever-evolving role of the quantity surveyor, and the prominent role that quantity surveyors now assume throughout the project life-cycle. Moreover, I hope this edition also impresses on the reader the importance of collaborative working between the design team members at the earliest possible stages of the project, and the role that cost planners have in the briefing process. The impact that whole life-cycle costing now has on the cost planning process is also reinforced in this edition.

Many of the principles of elemental cost planning and the techniques used in building up the cost plan etc., have stood the test of time and thus remain unchanged. There is still a great deal of original material in this edition; those readers familiar with the text will no doubt take comfort in this, and I hope that I have struck the right balance between new and old.

I wonder what challenges the construction professions, and in particular the cost planners, will face in the future? The mouth-watering prospect of massive capital investment in built assets around the east of London in time for the 2012 Olympics presents a real opportunity to demonstrate the innovative, dynamic and professional way in which the UK construction industry can deliver prestigious schemes. I hope that this book helps the current crop of undergraduates in quantity surveying, construction management or any other discipline to understand the fundamental importance of effective cost planning, and that they will take this knowledge and be part of something that will change many people’s lives for the better. That is the real beauty of the construction industry – you can have a tangible stake in improving people’s lives for the better!

Richard Kirkham

Liverpool John Moores University

February 2007

Preface to the First Edition

This book is intended as an introduction to cost planning for practising quantity surveyors and as a textbook for students taking the Final Examination (Quantities Part II) of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, or the Third Examination of the Institute of Quantity Surveyors. I have therefore assumed that the reader is already familiar with the ordinary processes of quantity surveying, particularly the preparation of bills of quantities, and this is taken for granted in the text; nevertheless I hope that the book may be read with advantage by members of allied professions.

I have tried to present the subject in a way that will be helpful to the surveyor coming to grips with it for the first time, and have concentrated on explaining the basic principles, basic methods and some of the main pitfalls. I have not tried to reprint the masses of tables, charts and detailed examples which have appeared in the technical press, as once the principles have been understood the reader will find that lack of time rather than lack of material will limit his further studies.

I have received a good deal of assistance in the compilation of this work from the various organisations which are mentioned therein, but I would particularly like to mention the help given by the officers of Hertfordshire County Council Architects Department and the Building Cost Advisory Service of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Douglas J. Ferry

Belfast

June 1964

Nomenclature and Acronyms

| ∑ | the sum of (sigma notation) |

| P | the principal (in investment terms) |

| i | the rate of interest |

| n | time (ordinarily number of years) |

| r | discount rate or real discount rate (in STPR calculations) |

| ρ | catastrophe risk and pure time preference (in STPR calculations) |

| µ | elasticity of the marginal utility of consumption (in STPR calculations) |

| g | output growth |

| t | time |

| ≈ | approximately equal to |

| Л | pi (3.142 to 3 d.p.) |

| σ | standard deviation |

| ACostE | Association of Cost Engineers |

| AFS | ascertained final sum |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| AIRR | adjusted internal rate of return |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BCIS | Building Cost Information Service |

| BMI | Building Maintenance Information Service |

| BP | back propagation |

| BQ | bill of quantities |

| BSI | British Standards Institute |

| CAAD | Computer Aided Architectural Design |

| CABE | Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment |

| CATO | Computer Aided Taking Off System |

| CBC | Co-ordinated Building Classification |

| CBS | cost breakdown structure |

| CDM | Construction Design and Management Regulations 1994 |

| CIBSE | Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers |

| CIOB | Chartered Institute of Building |

| CIRIA | Construction Industry Research and Information |

| CIS | Construction Information Service |

| CITE | Construction Industry Trading Electronically |

| CM | construction manager or construction management (in procurement) |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| CQS | contractor’s quantity surveyor |

| D&B | design and build |

| DCF | discounted cash flow |

| DPM | damp-proof membrane |

| DCMF | Design, Construct, Manage and Finance |

| EAC | equivalent annual cost |

| ECC | Engineering and Construction Contract |

| E-procurement | electronic procurement |

| EST | Energy Saving Trust |

| FV | future value |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GFA | gross floor area |

| GMP | guaranteed maximum price |

| HGCRA | Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 |

| HMRC | Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs |

| ICE | Institution of Civil Engineers |

| IPD | Institute for Professional Development |

| IRR | internal rate of return |

| ISO | International Standards Organisation |

| IT | information technology |

| ITOCC | Occupiers International Total Occupancy Cost Code |

| JCT | Joint Contracts Tribunal |

| KM | knowledge management |

| LA | local authority |

| LCC | life-cycle costing |

| MARR | minimum acceptable rate of return |

| MC | management contracting |

| MCDM | multi-criteria decision-making |

| MLR | minimum lending rate |

| M&E | mechanical and electrical |

| MTC | measured term contract |

| NAO | National Audit Office |

| NEC | New Engineering Contract |

| NPS | National Procurement Strategy |

| NPV | net present value |

| NR | Network Rail |

| No | number (of) |

| NS | net savings |

| OGC | Office of Government Commerce |

| PC | practical completion |

| PFI | Private Finance Initiative |

| POCA | Property Occupancy Cost Analysis |

| PPP | Public Private Partnership |

| PQS | private practice quantity surveyor |

| PSA | Property Services Agency |

| PSC | Public Sector Comparator |

| PV | present value |

| QS | quantity surveyor |

| RC | reinforced concrete |

| RIBA | Royal Institute of British Architects |

| RICS | Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors |

| SBC | Standard Building Contract |

| SCQS | Society of Construction Quantity Surveyors |

| SFCA | Standard Form of Cost Analysis |

| SIR | savings to investment ratio |

| SMM7 | Standard Method of Measurement of Building Works, |

| SPV | Special Purpose Vehicle |

| STPR | social time preference |

| TPI | Tender Price Index |

| TPISH | Tender Price Index of Social Housing |

| VAT | value added tax (17.5% at time of writing) |

| WLCC | whole life-cycle costing |

Acknowledgements

I would like to express sincere gratitude to Dr Halim Boussabaine (University of Liverpool) for his patience and friendship; updating this text has diverted my time from other activities and had it not been for him, many initiatives we organised would simply not have happened. Similarly, thanks to Mr John Lewis of the same institution, for some useful additions to this text.

Thanks also to the following at Liverpool John Moores University: Mr Bill Atherton for his splendid illustration skills and willingness to cover the odd lecture; Mr John McLoughlin for the production of the diagrams in Chapter 9; Dr Fiona Borthwick and Dr Clare Harris who offered moral support throughout; Anne Roberts and her team in the school office who accommodated my tardiness with the paperwork from time to time, and finally my fellow colleagues on the ‘green mile’.

Dr John Schofield, my friend and colleague, chair of the Independent Monitoring Board at HM Prison Altcourse, moved earth and high heaven to accommodate my workload around the duties of the board. His support has been invaluable, and I thank him most sincerely.

Finally to Joanne, Liverpool’s finest district nurse, who has had to put up with the kitchen resembling the University Library for quite some time!

About the Authors

Douglas J. Ferry PhD, FRICS formerly Dean of Architecture and Building, New South Wales Institute of Technology and Research Manager with CIRIA. Douglas authored the very first edition of this text in 1964 whilst based at the College of Technology, Belfast where he lectured in quantities and building construction. In that same year he also published Rationalisation of Measurement with the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Peter S. Brandon DSc, DEng, MSc, FRICS is Director of Salford University ‘Think Lab’ and Director of Strategic Programmes, School of the Built Environment, University of Salford. Formerly Pro-Vice Chancellor (Research and Graduate College) at the University, he was the inaugurator of several high profile initiatives including Construct IT, the national network for Information Technology in Construction which received the Queen’s Anniversary Prize in 2000; SURF, the Centre for Sustainable Urban and Regional Futures; CCI, The Centre for Cnstruction Innovation and the BEQUEST international network.

Jonathan D. Ferry BSc(Hons) is a Manager of Procurement in Projects working for Tube Lines Limited under the London Underground PPP, and was previously a Director of Dearle and Henderson.

Richard J. Kirkham BA(Hons), PhD (Liverpool), MACostE, ICIOB is a Senior Lecturer in Construction Management at the School of the Built Environment, Liverpool John Moores University. His research interests are in whole life-cycle costing, quantitative risk analysis, stochastic modelling techniques and performance measurement for public sector facilities. Prior to this, he worked as a Research Officer at Cranfield University. He has published widely in the field of whole life-cycle cost modelling and is co-author of Whole Life-Cycle Costing: Risk and Risk Responses. He is a series editor of the RICS Research/Blackwell Construction Series and is Scientific Secretary of CIB-TG62 Complexity and the Built Environment. Richard is a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society, an Incorporated Member of the Chartered Institution of Building (Vice Chair Liverpool Centre 2006/7 and Chair 2007/8) and was elected a Member of the Association of Cost Engineers in 2004.

About the Contributors

Mr Brian Greenhalgh BSc, MBA, FRICS, FCIOB is currently Head of External Affairs in the School of the Built Environment at Liverpool John Moores University where he specialises in the procurement and management of construction projects. After qualifying as a Chartered Quantity Surveyor, he worked both nationally and internationally before joining the Liverpool Polytechnic. He has served on RICS committees both locally and nationally and has lectured widely on aspects of construction management and contract administration.

Mr Anthony Waterman BA (Hons), MSc (University College London) is Head of Research at Sense Cost Consultancy, a division of Mace. Prior to joining Sense, Anthony worked as a Principal Consultant at the Building Research Establishment after completing his Master’s degree in Construction Economics. At BRE he worked on various aspects of whole life-cycle costing and performance modelling, including the development of PSC models for Prime Contracting and PFI schemes and has published several reports and papers.

Buildings lie at the very heart of our everyday lives. We live and work in them; they provide the very means by which modern civilisations function, but it is because of this that it is easy to underestimate their importance. Buildings and structures facilitate the provision of healthcare, education, commerce and justice. In other words, buildings provide not only enclosure but also de facto social capital.

Notwithstanding the value1 aspects of buildings, the construction industry generally is inextricably linked with money. Simply put, buildings cost money, and usually lots of it. This may seem a rather simplistic contention but history reveals that understanding the costs of construction is a skill that has developed over time. In the seventh edition to this text, Douglas Ferry and Peter Brandon referred back to biblical times in order to trace the origins of cost planning, and the reading they quoted from St Luke (Ch.14) gives a fascinating insight:

Would any of you think of building a tower without first sitting down and calculating the cost, to see whether he could afford to finish it? Otherwise, if he has laid its foundations and then is not able to complete it, all the onlookers will laugh at him. ‘There is the man’ they will say ‘who started to build and could not finish’.

Whilst there are clearly metaphorical connotations within this reading, the point is pretty clear. To build well you must first plan. Interestingly, the final part of the reading is a harrowing reminder to many clients and builders in today’s society who have no taken heed of good budgetary management.

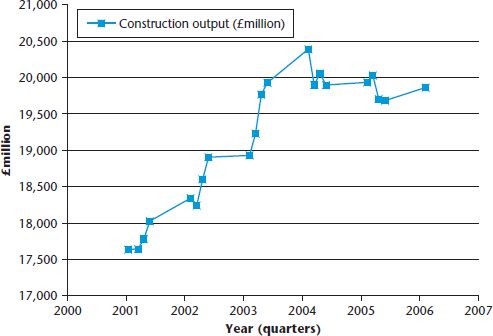

Figure 1.1 Quarterly construction output.

Chapter 7 will consider the relationship between costs of buildings and procurement, procurement being the method by which buildings are delivered to the client. The UK in particular has seen a rapid increase in construction output since the year 2000 (see Figure 1.1), but allied to this has been an increasing focus on project budgets, and moreover the ability to deliver these projects to the projected cost.

Sadly, several high profile construction projects in the UK have been plagued with problems over programme and budget. With public sector construction projects there is a strong emphasis on meeting the budget, so when the project runs into financial difficulties, the taxpayer and media become rather unsympathetic. Some recent examples include the following.

The new national stadium at Wembley is a project that has been mired in controversy with questions over adequate cost planning and budget management. Initially, the cost of the north London stadium was expected to be approximately £200 million. However, in the summer of 2006 the projectedcost had increased to some £715 million. The Football Association and Rugby League Challenge Cups, along with a host of other events, were relocated to other stadia as the project rolled on beyond the anticipated completion date.

The project has become the subject of intense media speculation and on 17 July 2006, the Minister of State for Culture, Media and Sport, Richard Caborn, was asked to make a declaration on the target for practical completion. He stated that he was confident that substantial completion of the stadium would be achieved in July 2006, sufficient to enable practical completion (PC) by September 2006. PC was eventually achieved in 2007.

So what happened to the cost plan? The contractors have disputed the projected final cost, arguing that the £715 million figure is the ‘cost shown to the banks so that they know that [we] can finance that amount should we need to’.

A combination of factors led to the problems faced by the project team; however, an article in The Economist in mid-20052 suggested that ‘an unanticipated rise in the cost of steel (which doubled in 2004) and the extra labour required to ensure the building is ready for the May FA Cup Final [threw] the management’s calculations out of kilter’.

The steelwork issue certainly had a significant impact, not only on the cost plan but also the contractual arrangements between the principal contractor Multiplex and steelwork contractor Cleveland Bridge UK. Early on in the project, Cleveland Bridge entered into a £60 million lump sum contract to design, fabricate, deliver and erect the structural steelwork at Wembley Stadium, including the bowl and huge steel arch3. However, in late 2003, Cleveland Bridge and Multiplex entered into formal dispute as the latter argued that it was haemorrhaging cash as a result of market conditions and specific project issues, and it sought significant variation payments or a change to a cost plus contract arrangement. This dispute continued in court as this book went to press.

As with Wembley Stadium, the construction of the new Scottish Parliament Building at Holyrood in Edinburgh was shrouded in controversy, resulting in a public enquiry led by Lord Fraser of Carmyllie. In May 1997, the recently elected Labour Government committed to holding a referendum on devolved government in Scotland. In the referendum held on 11 September 1997 almost 75% of those voting agreed that there should be a Scottish Parliament. A new building to house the Parliament was therefore required and in a subsequent white paper it was estimated that the cost of constructing a new Parliament would be between £10 million and £40 million. This estimate was made prior to the identification of a location or a design.

Good cost planning requires critical engagement from all project stakeholders from the outset, and a unified voice of opinion from the client. This was not the case and it could be argued that on this project there was no client. However, one of the most catastrophic decisions to affect the project in terms of cost and progress was the procurement route selected. In his opening speech prior to publication of his report, Lord Fraser said:

As I have said in my Introduction, while I have a number of sharp criticisms and recommendations to make on matters which ought to have been much better understood, there is no single villain of the piece. There were, however, some catastrophically expensive decisions taken and principal among those was the decision taken – not cleared with Ministers – to follow the procurement route of construction management. I have very real doubts if the extent of the risk remaining with the public purse was properly understood at the time it was adopted and I remain concerned that it was not clearly grasped by the Scottish Parliament for nearly two years after the Project was handed over to the SPCB [Scottish Parliament Corporate Body] when the Parliament gave up trying to have a ‘budget’ for the building. Any building constructed under the procurement model of construction management costs what it costs.

Lord Fraser’s report could not be damning enough of the fact that the project did not have a cost plan. Inadequate briefing was in part responsible for this (some argue that there was no brief at all); the importance of developing a brief and its relationship with the cost plan is covered in this first section of the book. The reader is also encouraged to refer to the further reading sections at the end of the chapters, for further information on briefing.

The relationship between cost planning, procurement route selection and the brief was a key feature of the British Library project in London, which by project completion in 1988 had amassed a net increase of £58 million on the original planned cost. Like the other projects described in this chapter, a catalogue of errors occurred which led to the final cost of the project coming in at some £500 million. Principal among these was the decision to adopt the construction management procurement strategy. The National Audit Office (NAO) report heavily criticised this decision, and quite surprisingly Lord Fraser did not allude to this in his Holyrood Enquiry report. Had he done so, the media would no doubt have rallied against the decision-makers in that lessons clearly had not been learned. This unsuitable method of procurement had a fundamental impact on the cost plan, as did the thousands of design changes and variations from the original brief, systematic failures in quality and cost control during production, and failures in the budgetary controls of contracts for the many different works packages undertaken by various subcontractors. The lack of experience in using construction management, alliedwith the complex nature of the architects’ and engineers’ contracts and the standard conditions for works contractors, led to a situation that could not possibly sustain the original cost plan. The result was a damning enquiry and an NAO report that was said to be the most critical assessment yet of a public construction project.

Cost planning as a process is difficult to define concisely as it involves a variety of procedures and techniques used concurrently by the quantity surveyor (QS) or building economist. Traditional cost planning will usually follow the conventional outline design, detailed design process. In a practical sense, the cost planning process starts with the development of a ballpark figure (or cost bracket) to allow the client to decide whether the project is feasible. More robust techniques for doing this are described in Chapter 5. This feasibility estimate is usually calculated on a unit cost method (e.g. cost per bed for a hospital, cost per student for a school). The estimate is then refined using the elemental method: the building is broken down into its component elements and sub-elements, usually using the Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) cost structure (Appendix B). The elemental method is a system of cost planning and control that enables the cost of a scheme to be monitored during the various stages of design development.

A good cost planning system should:

A direct benefit of good cost planning is to reduce project risk. Steps should be taken to ensure that project development budget opportunities and threats are fully identified and assessed.

Ferry and Brandon, in previous editions of this book, described the cost planning process in three phases:

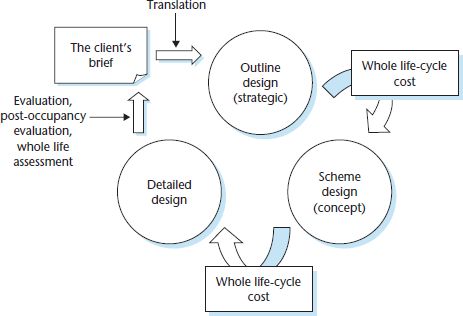

Figure 1.2 The conventional stages of the cost planning process, including whole life-cycle costing.

Current thinking suggests that cost planning should continue beyond the conventional boundaries and take into account the whole life rather than the period up to PC. Figure 1.2 shows the typical cost planning process, but importantly this is encapsulated within a whole life decision environment; in other words, it should include adequate appraisal of the long-term cost implications of design decisions (such as maintenance, energy and facilities management (FM) costs). This will be explored in depth in Chapter 7.

The functions of the quantity surveyor (QS) are broadly concerned with the commercial management of construction projects. This breaks down into two areas of work: the planning and control of project costs, and the management of the terms and conditions of the form of contract agreed by the parties (client and contractor). In this book the first area will be considered.

The planning and control of construction costs cover a range of activities, which may include feasibility studies, cost planning, value engineering, cost–benefit analysis and life-cycle costing, which all take place during the design stage of projects; and the calculation of interim valuations and final accounts, including the cost estimation of variations and changes, which are procedures that take place during the construction stage of the project. QSs can also be known as construction economists, cost engineers or construction commercial managers.

The quantity surveying profession can trace its roots back to the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666. Before that date, buildings tended to be built on what we now call a design build arrangement, where the client would give the builder an outline of what was wanted, and the master builder would work out the details, arrange all the specialist tradesmen and forward the bills to the client at regular intervals. The difficulty with this arrangement was that the client did not know how much the building was likely to cost before it was finished, and if the client wanted several estimates or quotations4, each builder would need to calculate the amount of materials, plant and labour required, with the obvious duplication of effort and cost.

With so much rebuilding work required after the Great Fire, a more efficient system of calculating building costs and generating estimates was clearly required. So the independent QS was born, whose role was originally to consider the architect’s drawings (and specifications if they were lucky) and to develop a ‘Bille of Quantityes’, with the purpose of allowing any firm who wished to tender for a project to calculate that tender on the same basis and therefore minimise duplication of effort. This service was originally paid for by the contractors tendering for the work, but over time the role became part of the responsibilities of the client’s side, to make sure that all tenderers were issued with identical tender documents.

Up to the beginning of the twentieth century, most large-building construction work was either procured by the government or by private individuals, where cost was not seen as the main criterion. Infrastructure work was slightly different and the considerable amount of canal building in the eighteenth century and railway construction in the nineteenth century was undertaken at considerable expense by corporate organisations. These companies (the railway companies prior to nationalisation) would borrow money from the capital markets to build the permanent way (or P-way as they referred to it) and rolling stock, and they raised revenue through ticket sales to passengers and charging for freight. However, most railway construction projects were grossly over budget, and for all Brunel’s image as an icon of railway engineering, he was constantly being sued by construction firms for non-payment of bills on projects where he had lost control of expenditure. Clearly, a further change was required.

The quantity surveying profession therefore took the initiative, spurred by the development of what is now the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) in 1868, and developed procedures to control construction costs by accurate measurement of the work required and the application of expert knowledge of costs and prices of work, labour, materials and plant. Some time later, they would use their understanding of construction technology to assess the implications of design decisions at an early stage, to ensure good value for money.

The technique of measuring quantities from drawings and specifications prepared by designers, principally architects and engineers, in order to prepare tender/contract documents, is known in the industry as ‘taking off’. The quantities of work taken off are used typically to prepare bills of quantities (BQs), which traditionally have been prepared in accordance with one of the published standard methods of measurement as agreed by the quantity surveying profession and representatives of contractor organisations.

Although all QSs will have followed a similar course of education and training (usually to degree level for those entering the profession today), there are many areas of specialisation in which a QS may concentrate. The main distinction between QSs is those who carry out work on behalf of a client organisation, often known as a professional quantity surveyor (private practice QS or PQS), and those who work for construction companies, often known as a contractor’s quantity surveyor. The latter is usually responsible for all legal and commercial matters within the contracting organisation and because of this many are now termed commercial managers.

The innovations in procurement since the mid-1990s have radically changed the professional remit of QSs and other building professionals involved in providing strategic advice to clients on procurement and design. The design and economics of construction are inextricably linked with the procurement process, and this is recognised in the tranche of documentation issued by the Office of Government Commerce (OGC) under the umbrella of ‘Achieving Excellence in Construction’5.

Achieving Excellence in Construction was launched in March 1999, by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, to improve the performance of central government departments, executive agencies and non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs) as clients of the construction industry. It put in place a strategy for sustained improvement in construction procurement performance and in the value for money achieved by government on construction projects, including those involving maintenance and refurbishment.

Key aspects include the use of partnering and development of long-term relationships, the reduction of financial and decision-making approval chains, improved skills development and empowerment, the adoption of performance measurement indicators and the use of tools such as value and risk management and whole life-cycle costing (WLCC).

With all these changes, QSs are now seen as the financial managers of the construction team who add value by monitoring time and quality as well as the traditional function of cost. The role of QSs has therefore changed significantly from its humble origins and they are now responsible for ascertaining a long-term view of building projects, assessing options and providing clients with comprehensive information on which to base investment decisions.

The profession of quantity surveying is a peculiarly British institution, owing chiefly to the historical context outlined above. Through emigration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the British construction procurement system has been exported to Commonwealth countries, so that in English speaking countries such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada, there are well-established firms of QSs represented by their own national professional bodies. The construction industries in these countries have developed separately, showing that the skills of the QS have been found to be valuable. In Europe, the pre- and post-contract roles are generally split, so the feasibility and cost planning function is taken by the économiste de la construction in France or the baueconomist in Germany. The post-contract function of valuations and final account preparation is often taken by the resident engineer, assisted by a technician cost engineer. In the USA the situation is substantially the same, although many large firms of QSs are now operating very successfully where clients see the considerable value of core QS skills in technology, law and economics. Traditionally, these skills were held by different professions who did not necessarily have detailed knowledge of the construction industry.

Cost planning, like any other discipline within construction, is continually developing and responding to the ever-changing demands of today’s clients. In order to meet this challenge, planners should acquire and continue to develop over their careers a basic set of competences. This book aims to provide the first step, but future cost planners must recognise the importance of:

Chapter 2 examines some of the recent developments in cost planning discipline and highlights potential future advances.

Notes

(1) The concept of value is based on the relationship between satisfying needs and expectations, and the resources required to achieve them.

(2) ‘Project management: Overdue and over budget, over and over again.’ The Economist, 9 June 2005.

(3) ‘Ruthless but lawful.’ QS News, 14 July 2006.

(4) The difference between an estimate and a quotation is very important. An estimate is only an indication of what the cost of the project will be and may change if, for example, material or labour prices change. A quotation, on the other hand, is a fixed price and will only change if the client varies their instructions.

(5) The full ‘Achieving Excellence in Construction’ documentation can be downloaded from the Office of Government Commerce website at www.ogc.gov.uk

Further reading

Ashworth, A. (2004) Cost Studies of Buildings.Prentice Hall, Harlow.

Ashworth, A. and Hogg, K. (2001) Willis’s Practice and Procedure for the Quantity Surveyor. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Brook, M. (2004) Estimating and Tendering for Construction Work. Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, Oxford.

Cartlidge, D. (2006) New Aspects of Quantity Surveying Practice. Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, Oxford.

Jaggar, D., Ross, A., Smith, J. and Love, P. (2002) Building Design Cost Management. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

The nature of construction procurement and the complexity of the relationships between the various actors in the project life-cycle have led to a new paradigm in the use of information technology (IT) supported cost planning systems. The gradual transition from paper-based planning and documentation to e-platforms has allowed the industry to offer better services to clients, whilst empowering construction professionals with the capability to capture knowledge from past projects and translate this into future best practice and service delivery – known as knowledge management (KM).