Table of Contents

Praise for ZIG ZAG

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction: Choosing Creativity

The Eight Steps

Mistakes We Should All Avoid

How to Make Use of This Book

The First Step: ASK: How the Right Questions Lead to the Most Novel Answers

The Practices

Onward . .

The Second Step: LEARN: How to Prepare Your Mind for Constant Creativity

The Practices

Onward …

The Third Step: LOOK: How to Be Aware of the Answers All Around You

The Practices

Onward …

The Fourth Step: PLAY: How to Free Your Mind to Imagine Possible Worlds

The Practices

Onward …

Solutions

The Fifth Step: THINK: How to Have Way More Ideas Than You'll Ever Need

The Practices

Onward…

The Sixth Step: FUSE: How to Combine Ideas in Surprising New Ways

The Practices

Onward…

The Seventh Step: CHOOSE: How to Pick the Best Ideas and Then Make Them Even Better

The Practices

Onward …

The Eight Step: MAKE: How Getting Your Ideas Out into the World Drives Creativity Forward

The Practices

How Do You Know When to Stop?

Conclusion

Learn to Choose the Right Step

Discover Your Own Style

Always Onward!

Appendix A Outline of All of the Steps, Practices, and Techniques

Ask

Learn

Look

Play

Think

Fuse

Choose

Make

Appendix B: The Research Behind the Eight Steps

References

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

“Finally! A creativity advice book that is grounded in scientific research.”

—Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

“Zig Zag is the most fun and most useful creativity book I have ever read. Keith Sawyer's gem sweeps you up with a host of great stories, quizzes, exercises, and teaches you one way after the other to be more creative.”

—Robert I. Sutton, professor of Management Science,\break Stanford University; author, Good Boss, Bad Boss and The No Asshole Rule

“In geometry the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. But in creative pursuits, Zig Zag shows us, it's anything but. Keith Sawyer is the most creative person writing about creativity I know.”

—Robert Mankoff, cartoon editor, The New Yorker; author, The Naked Cartoonist: A New Way to Enhance Your Creativity

“Creativity is essential in our journey to the future, and this gem of a book helps each of us on the way.”

—Tim Brown, CEO and president, IDEO; author, Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation

“Keith Sawyer is the best combination of a brilliant creativity researcher and storyteller around.”

—Peter Sims, author, Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries

“Zig Zag reveals the true nature of the creative process: improvisational, surprising, with unexpected twists and turns. The book is filled with hands-on activities that help you manage that process and keep it moving forward to a successful creative outcome.”

—Josh Linkner, author, Disciplined Dreaming: A Proven System to Drive Breakthrough Creativity

Cover design by John Hamilton

Cover image: © Alicat/iStockphoto

Copyright © 2013 by Keith Sawyer. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Imprint

One Montgomery Street, Suite 1200, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594— www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The collaborative sketching figure in Chapter 8 is adapted from figure 2 on page 170 of; Shah, J. J. et al. (2001). Collaborative sketching (C-Sketch). Journal of Creative Behavior, 35(3), 168– 198. Copyright © Wiley; reprinted with permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sawyer, R. Keith (Robert Keith)

Zig zag : the surprising path to greater creativity / by R. Keith Sawyer, Ph.D.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-29770-4 (cloth), 978-1-118-53911-8 (ebk.), 978-1-118-53922-4 (ebk.),

978-1-118-53926-2 (ebk.)

1. Creative ability. I. Title. II. Title: Zig zag.

BF408.S288 2013

153.3′5— dc23

2012042028

first edition

To my son, Graham

Choosing Creativity

Creativity doesn't always come naturally to us. By definition, creativity is something new and different; and although novelty is exciting, it can also be a little scary. We're taught to choose what's familiar, to do what's been done a thousand times before. Soon we're so used to staying in that well-worn rut that venturing into new terrain seems an enormous and risky departure.

But rest assured—you already have what it takes to be creative. Neuroscience and psychology have proven that all human beings, unless their brain has been seriously damaged, possess the same mental building blocks that inventive minds stack high to produce works of genius. That creative power you find so breathtaking, when you see it tapped by others, lives just as surely within you. You only have to take out those blocks and start playing with them. How, though?

In fact, the journey's pretty simple. In this book, I share with you the eight steps that are involved in being creative. Once those steps become second nature to you, creativity won't seem rare and magical and daunting. You'll stop being scared of writer's block or stupid ideas or a blank canvas or a new challenge, and your creative power will be flexible, versatile, and available in unlimited supply. All you have to do is learn how to tap it. And that's the purpose of the exercises in Zig Zag.

I started thinking about creativity many years ago, when I graduated from MIT with a computer science degree and found myself designing video games for Atari. Since then I've played jazz piano and studied how jazz musicians collaborate; earned a doctorate in psychology at the University of Chicago and studied how Chicago's improv companies create on the spot; researched theories of creativity in education; and studied how artists and sculptors teach creativity.

No matter what kind of creativity I studied, the process was the same. Creativity did not descend like a bolt of lightning that lit up the world in a single, brilliant flash. It came in tiny steps, bits of insight, and incremental changes.

Zigs and zags.

When people followed those zigs and zags, paying attention to every step along the way, ideas and revelations started flowing. Sometimes those ideas did feel like gifts, arriving unsolicited at the perfect time. But in reality, a lot of daydreaming, eclectic research, wild imagination, and hard choices had paved the way.

It's lucky we do all have creative potential, because we need it more than we realize. You might think of creativity only in a single context, as a quality you pull out when it's time for a weekend craft project or a crazy practical joke. But you can use creativity to

Think of a challenge, need, or issue that you face right now. Something that you care about and just don't know how to deal with; something that is frustrating you or feels like an impasse. Scribble this challenge on a Post-it note (now there was a creative product idea!) and stick it to this page. Scribble a few more, if you like; you can plaster the page with them.

Here are some examples that most of us have faced at some point in our lives:

At your job, your problem might be more immediate and concrete:

In many professions, the problems can get so specific and so technical that only you know how to phrase them. As a psychology professor, I face challenges like the following:

As you read the techniques in this book, keep thinking of your Post-it challenges, and play with these techniques to find a creative solution.

I've spent more than twenty years as a research psychologist studying how creativity works. I've explored the lives of exceptional creators and learned the backstories of world-changing innovations. I've reviewed laboratory experiments that delved deep into the everyday creativity that all of us share.

To write this book, I distilled all that research into eight powerful, surprisingly simple steps. Follow them, and you zig zag your way to creativity.

Much of what's been written about creativity until now has romanticized it, invoking the divine Muses or the inner child or the deep subconscious. Creativity glows like an alchemist's gold, always mysterious and just out of reach, but promising utter transformation. That's a clever trick, and people have made millions on it. They've convinced us that creativity is a rare gift conferred on a handful of special individuals, and the rest of us can only stumble along in the dark, hoping some of that glittering dust will fall on our upturned faces.

These eight steps aren't the exclusive property of exceptional individuals. I repeat: we all have these abilities. And the latest research in psychology, education, and neuroscience shows that they can, without a doubt, be practiced and strengthened.

This book is your personal trainer, coaching you through the eight zig zagging steps of creativity. Before I started to write, I spent a long, patient year reading countless books that claimed to increase your creativity. Some of them were brand-new, some were decades old, and some recycled the wisdom of the ancients. Most of them contained at least some good advice; but because they weren't grounded in research, that good advice was usually mixed with myths and mistakes. Still, in just about every book, I found at least one or two hands-on activities, exercises, and games that aligned perfectly with the latest research findings on human creativity. I organized the best of these classic creativity games and exercises into the eight steps. Then I added many of my own hands-on exercises, which I created just for this book and are based on new research about successful creative thinking.

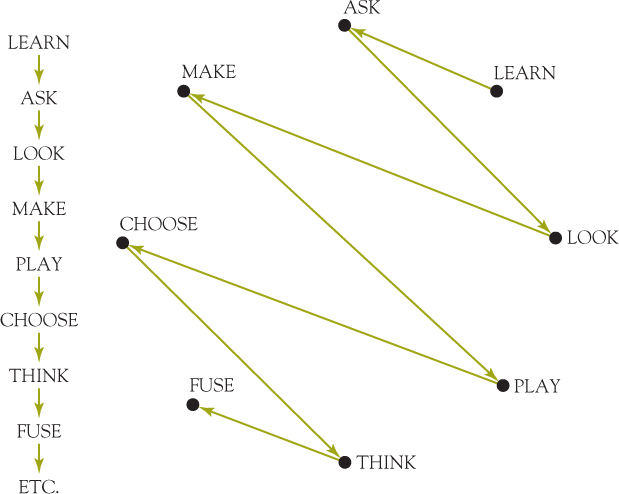

Here are the eight steps, with short descriptions so you can see how they fit together:

1. Ask. Creativity starts with a penetrating research question, a startling vision for a new work of art, an urgent business challenge, a predicament in your personal life. Mastering the discipline of asking means you're always looking for good problems, always seeking new inspiration. You know where you're going, and yet you're receptive to questions that emerge unexpectedly.

1. Ask. Creativity starts with a penetrating research question, a startling vision for a new work of art, an urgent business challenge, a predicament in your personal life. Mastering the discipline of asking means you're always looking for good problems, always seeking new inspiration. You know where you're going, and yet you're receptive to questions that emerge unexpectedly. 2. Learn. In a creative life, you're constantly learning, practicing, mastering, becoming an expert. You seek out knowledge not only in formal classrooms but also from mentors, experts, books, magazines, film, Web sites, nature, music, art, philosophy, science …

2. Learn. In a creative life, you're constantly learning, practicing, mastering, becoming an expert. You seek out knowledge not only in formal classrooms but also from mentors, experts, books, magazines, film, Web sites, nature, music, art, philosophy, science … 3. Look. You are constantly, quietly aware. You don't just see what you expect to see. You see the new, the unusual, the surprising. You see what others take for granted, and what they incorrectly assume. You expose yourself to new experiences eagerly, without hesitation; you regularly seek out new stimuli, new situations, and new information.

3. Look. You are constantly, quietly aware. You don't just see what you expect to see. You see the new, the unusual, the surprising. You see what others take for granted, and what they incorrectly assume. You expose yourself to new experiences eagerly, without hesitation; you regularly seek out new stimuli, new situations, and new information. 4. Play. The creative life is filled with play—the kind of unstructured activity that children engage in for the sheer joy of it. You free your mind for imagination and fantasy, letting your unconscious lead you into uncharted territory. You envision how things might be; you create alternate worlds in your mind. “The debt we owe to the play of imagination,” Carl Jung wrote, “is incalculable.”

4. Play. The creative life is filled with play—the kind of unstructured activity that children engage in for the sheer joy of it. You free your mind for imagination and fantasy, letting your unconscious lead you into uncharted territory. You envision how things might be; you create alternate worlds in your mind. “The debt we owe to the play of imagination,” Carl Jung wrote, “is incalculable.” 5. Think. The creative life is filled with new ideas. Your mind tirelessly generates possibilities. You don't clamp down, because you realize most of these ideas won't pan out—at least not for the current project. But successful creativity is a numbers game: when you have tons of ideas, some of them are sure to be great.

5. Think. The creative life is filled with new ideas. Your mind tirelessly generates possibilities. You don't clamp down, because you realize most of these ideas won't pan out—at least not for the current project. But successful creativity is a numbers game: when you have tons of ideas, some of them are sure to be great. 6. Fuse. Creative minds are always bouncing ideas together, looking for unexpected combinations. Successful creativity never comes from a single idea. It always comes from many ideas in combination, whether we recognize them or not. The creative life doesn't box its concepts into separate compartments; it fuses and re-fuses them.

6. Fuse. Creative minds are always bouncing ideas together, looking for unexpected combinations. Successful creativity never comes from a single idea. It always comes from many ideas in combination, whether we recognize them or not. The creative life doesn't box its concepts into separate compartments; it fuses and re-fuses them. 7. Choose. A creative life is lived in balance, held steady by the constant tension between uncritical, wide-open idea generation (brainstorming, done right) and critical examination and editing. Choosing is essential, because not all ideas and combinations are ideal for your purposes. The key is to use the right criteria to critique them, so you can cull the best and discard any that would prove inferior, awkward, or a waste of your time.

7. Choose. A creative life is lived in balance, held steady by the constant tension between uncritical, wide-open idea generation (brainstorming, done right) and critical examination and editing. Choosing is essential, because not all ideas and combinations are ideal for your purposes. The key is to use the right criteria to critique them, so you can cull the best and discard any that would prove inferior, awkward, or a waste of your time. 8. Make. In the creative life, it's not enough to just “have” ideas. You need to make good ideas a reality. You continually externalize your thoughts—and not just the polished, finished ones. You get even your rough-draft, raw ideas out into the world in some physical form, as quickly as possible. Making—a draft, a drawing, a prototype, a plan—helps you fuse your ideas, choose among them, and build on what you like.

8. Make. In the creative life, it's not enough to just “have” ideas. You need to make good ideas a reality. You continually externalize your thoughts—and not just the polished, finished ones. You get even your rough-draft, raw ideas out into the world in some physical form, as quickly as possible. Making—a draft, a drawing, a prototype, a plan—helps you fuse your ideas, choose among them, and build on what you like.To solve a particular problem, the simplest approach is to work through the steps in order:

Other books about creativity tend to stick to this linear process: spot the need or opportunity first, then identify the problem (ask), then gather information (look), then look for ideas (think), then select an idea (choose), and finally implement the idea (make). But as psychology and neuroscience are showing us, the creative process is far richer than that—and far less rigid. When you begin to master the eight steps, you'll start to zig and zag:

For example, although making seems to happen most naturally at the end of the eight steps, you can use its techniques to enhance the other seven steps, too. Making your ideas can help you fuse them, and choose the right ones. Making your daydreams can help you play more effectively. Making the things you see each day while looking can help you translate those sights into new ideas, or clarify your original question, or realize what you still need to discover.

Don't try to jump ahead to think and immediately have a bunch of ideas; creativity doesn't work that way. You have to follow the zigs and zags. You might not be focused on the right problem because you haven't asked the right question. You might not have the information you need because you haven't learned enough. You might not have explored the spaces and alternatives through the play that generates ideas.

Once you get comfortable with the rhythm of zigging and zagging, you'll be able to use the steps as you need them, without a rigid, linear order. In truth, any of the eight steps can play a role at any stage of creativity. After a great idea has emerged, no one can remember exactly where it started. But you can be sure that the looking continued through the final revisions, and the asking was repeated with each tiny decision about a detail in the finished work.

Exceptional creators often zig zag through all eight steps, in varying order, every day. That's part of the secret, because the steps work together to generate successful creativity. Each step feeds the other seven.

Many creativity books touch on some of these eight steps, but most of them emphasize thinking of new ideas and neglect the other seven steps. That's like waiting for a crop without sowing any seeds. If you want to do more than “be creative” for a minute or two, you need regular access to all eight steps. When you follow them, you experience a steady flow of small, good ideas. You come to expect those ideas to materialize, and they do. You can't know when they'll arrive, and you can't know what they'll look like. But you can trust the eight steps to bring them to you.

Zig Zag gives you, I hope, a more complete, original, and easily mastered way of seeing the world, making connections, solving problems, and overcoming obstacles. It's a handbook of proven techniques, based in solid scientific research about creativity and the brain. For my part, I've found it exhilarating to learn, with all the certainty today's neuroscience can bring, that creativity is not a mystery. There are proven techniques for enhancing creativity, and they are within anyone's reach.

There are two common mistakes that people make when they decide they need to be more creative. Following the zig zag way can help you avoid these errors.

Many people think of creativity as something you need only once in a while, when your normal habits and skills fail. So you wait until you face a serious challenge, something different from anything you've ever dealt with before, and only then do you decide that creativity is the answer. You're right, of course—creativity is the answer. But the mistake is waiting until the last minute and then hoping to suddenly become creative, for just long enough to solve the problem at hand. As therapist and author Martha Beck once wrote, “Don't wait for catastrophe to drive you to the depth of your being. Go there now; then you'll be ready.”

This process can help you respond to a sudden challenge, but the real benefit comes when you practice the eight steps every day. Then, instead of reacting to unexpected problems, focused on the past, you'll be finding promising opportunities that drive you forward into the future.

Often we think that a creative solution to a problem will be a single thought that dawns on us in a moment of clarity. To the contrary: studies of creativity show that it rarely arrives as a single brilliant idea. Rather, creative solutions to life's problems are lit by many small creative sparks—what Virginia Woolf described as “little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.” Creativity works by collecting these sparks as you zig zag forward, until suddenly they give off enough light to reveal a solution.

Wouldn't it be better to have these small sparks happening all the time, and accumulating before you face a serious problem? Imagine having a backlog, a notebook of good ideas that you could draw on whenever you needed it. The eight steps teach you that kind of proactive creativity. It's already in your power to produce this type of creativity, and it's far more effective than reactive creativity.

As you read this book, you'll realize why the second mistake, the “insight” myth, is so dangerous. It makes creativity sound slick and easy: the flash of insight comes, and presto change-o, your problem is solved. The danger is that when you don't have that one big flash, you conclude, “I'm not creative.”

And you're wrong.

Practicing the eight steps does take some work; you have to invest a bit of effort every day to keep those small creative sparks coming. You concentrate, you commit a measure of your precious time and energy, and you persist. Luckily, the practices are more delightful than demanding, and the discipline soon comes naturally.

If creativity just meant sitting around waiting for a lightning bolt, then you wouldn't be able to learn much about it from any book. It would be inexplicable, a kind of magic outside your control. Luckily for all of us, that's not how creativity works. Creativity is not a trait or a property or a gift. It's a set of behaviors. “Inspiration is for amateurs,” said the prolific painter Chuck Close. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

How long will it take for the eight steps to lead you to creativity? For some people, a week or two; for others, maybe six months or a year. The time frame depends on how thoroughly you practice the steps and how readily you let old anxieties and inhibitions slip away. Once you understand the process, you can sketch more loosely, come up with better ways to communicate with your boss, or write what novelist Anne Lamott calls “shitty first drafts” without being tempted to give up—because you'll know how to choose and refine and test those early steps.

What is certain is that you will continue to get better at the steps. Before you know it, you will have mastered them and made them your own—custom-tailored for your own creative domain, whether it's writing fiction, working in sales, or designing computer software. As circumstances change, the rhythm of your life speeds or slows, and you experiment with new kinds of projects, you can keep tweaking. You will zig and zag your way to constant creativity, every day. The basic steps won't change, and they will never let you down.

This is a practical book; it's meant to be used. The more you practice creativity, the more creative you become. So in each chapter, I take one of the eight steps, explain it, tell you why it works, and then give you practices that will let you master it. For each practice, there's an array of techniques, little exercises, or tricks or games that illustrate and enable you to hone that particular practice. Some you may need more than others; you'll know where to linger and when to move on. In the Conclusion, I provide additional advice about how to weave the eight steps together for maximum creativity, to finish your training as a zig zag master.

The techniques described in this handbook are not there simply to be read, tried once, and discarded with a check in the to-do box. They are there for you to use daily, in whatever way you need them. Keep the book nearby. Every day, make it a point to engage in at least one of the techniques. You'll soon find yourself doing this automatically, without even trying. But at the outset, open the book at random and choose one, or select one of the techniques matched to the step you've chosen to focus on that day.

I'd suggest you start by skimming through the book once, from start to finish. Or, you could take a quick glance at Appendix A, a concise map of all of the information in the book. That way you'll see the big picture of how the eight steps form a creative journey.

Then take the creativity assessment that follows. It will tell you which of the eight steps you're already good at, and which you'll want to shore up. That's where the techniques come in: once you've identified the steps you want to practice and polish, you can improve your creativity by using the techniques designated for each of those steps.

Now that you've completed the creativity assessment, you should better understand your strengths and where you might need additional exercise. And now you're ready to begin the zig zag path, starting with the first step, ask.

The First Step

ASK

How the Right Questions Lead to the Most Novel Answers

In 1983 Howard Schultz was working as the head of marketing for Starbucks, a small Seattle coffee bean company. In addition to roasting their own coffee beans, the four Starbucks stores sold high-end coffeemakers, bean grinders, and other brewing supplies. In spring 1983 the company sent Schultz to Italy to attend an international housewares show, to find new, cutting-edge coffee equipment it could sell in its stores.

Walking from his Milan hotel to the convention center, Schultz passed an espresso bar. He'd never seen one before, so he went in to look around. He found a classy environment, with opera music playing in the background. But although it was classy, it nonetheless felt comfortable; the barista—the sole employee in the store, the person operating the espresso machine—knew most of the customers by name, and chatted with them as they stood at the bar drinking their espresso. Schultz was fascinated. He spent the rest of his visit checking out other espresso bars all around Milan. He discovered that some of them were upscale and some were working class, but they all seemed to be like community centers—places where neighbors would gather to relax.

In one espresso bar, he overheard a customer order a caffé latte; he'd never heard of it, so he decided to order one too. He watched as the barista poured a shot of espresso, steamed some milk, and topped it off with foam. After one taste, Schultz thought to himself, “This is the perfect drink. No one in America knows about this. I've got to take it back with me.”

Schultz flew back from Milan to Seattle with a compelling creative challenge: “How can I recreate the Italian espresso bar in the United States?” Starbucks's three owners rejected his idea; they were happy with their successful retail business. They had no interest in turning their stores into restaurants or coffee shops. But they agreed to provide Schultz with seed money to start his own coffee shop, and they agreed to supply Schultz with their coffee beans.

Schultz left Starbucks in 1985, and in April 1986 he opened his first store, in downtown Seattle's busy business district. Going all out with his Italian vision, he called the store Il Giornale. It was truly the answer to his creative challenge: the decor was Italian, the menu had Italian words on it, and opera music was playing in the background. The baristas wore white shirts and bow ties. There were no chairs; you had to drink your coffee standing up.

Although the store was successful—three hundred customers the first day—it was obvious that the Italian model wasn't a good match with the laid-back culture of Seattle. Some people complained about the opera music, others wanted a place to sit, and virtually nobody understood the Italian on the menus. No one could even pronounce the name of the store (Eel Joe-rrnah-leh). So Schultz decided to ask a new question: “How can I create a comfortable, relaxing environment to enjoy great coffee?”

This was a much better question. After Schultz ditched the opera and Italian menus and added more chairs, Il Giornale started drawing up to one thousand customers each day. Schultz added two more stores. Just over a year after opening, the three Il Giornale stores were on track to make $1.5 million a year. Il Giornale was so successful that in August 1987 Schultz was able to buy out Starbucks, his coffee bean supplier. That gave him an opportunity to get rid of the last Italian feature of his stores: he renamed the Il Giornale stores and called them Starbucks.

The key to Schultz's success was asking the right question. Even outstanding creators don't know exactly what the right question is when they start out. But they're very good at paying close attention to cues that will lead them to a better question. Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen believes this is the secret of all successful entrepreneurs:

Research has shown . . . that the vast majority of successful new business ventures abandoned their original business strategies when they began implementing their initial plans and learned what would and would not work in the market. . . Guessing the right strategy at the outset isn't nearly as important to success as . . . a second or third stab at getting it right.

In early 2010 the hottest thing in phone apps was location, location, location. With its built-in GPS feature, your phone could tell you all sorts of useful things, like which friends were nearby and how to find the closest public toilet (or the closest Starbucks). Foursquare had just been released for the iPhone a year earlier, and the digerati were “checking in” to let their friends know wherever they happened to be.

A young programmer, Kevin Systrom, wanted a piece of the action. He had worked for Nextstop, Google, and an early version of Twitter, and he was ready to strike out on his own. Attracted by the success of foursquare, he started with a driving question: “How can I create a great location-sharing app?” The programming took only a few months, and the result was a simple iPhone app that let you check into a location, make plans for future location check-ins, earn points for hanging out with friends, and post pictures. Because he liked fine Kentucky bourbon whiskey, he named the app burbn.

Sad to say, it wasn't a big success. In retrospect, burbn was complicated to use, with a jumble of features that made it confusing. But around this time, a second programmer, Mike Krieger, joined Systrom. These two used a set of analytic tools to figure out what their customers were doing with burbn. Sure enough, they weren't “checking in” anywhere. But they were posting and sharing photos like crazy! Systrom and Krieger decided to ditch burbn completely and start with a new question: “How can we create a simple photo-sharing app?”

They began by studying all of the popular photography apps, and they quickly homed in on two main competitors. Hipstamatic was cool and had great filters, but it was hard to share your photos. Facebook was the king of social networking, but its iPhone app didn't have a great photo-sharing feature. Krieger and Systrom saw an opportunity to slip in between Hipstamatic and Facebook by developing an easy-to-use app that made social photo sharing simple. They chopped everything out of burbn except the photo, comment, and “like” features.

It took months of experimentation and prototyping to get everything just right. One of their early versions was called Scotch (Systrom liked scotch whisky, too) but it was slow and filled with bugs, and you couldn't use filters on your pictures. These various zigs and zags convinced them that the key to success was to make the app super easy. In their final version, you could post a photo in three clicks.

They renamed the app Instagram and launched it on October 6, 2010. On the first day, twenty-five thousand users signed up. They hit one million users in three months. Taking an idea from Twitter, they made every photo public by default. (When the pop sensation Justin Bieber joined, thousands of girls responded to every photo he posted, causing a huge spike in Instagram activity.) By April 12, 2012, when Facebook purchased Instagram for $1 billion, it had been installed on about 10 percent of all iPhones.

When Systrom built burbn, he was driven by the question, “How can I create a great location-sharing app?” It turned out to be the wrong question. Instagram succeeded because Systrom and Krieger were willing to dive deeper into this first step, ask. They looked closely at the failure of burbn, and they used that experience to figure out their next step: they found out what their users were doing (photo sharing); they studied the existing competition (Hipstamatic and Facebook); and they came up with a new question, “How can we create a simple photo-sharing app?” The answer to that new question led to thirty million users and $1 billion. In Silicon Valley today, this kind of shift in direction is called a “pivot.” I call it a zig zag.

Back in the 1970s many psychologists argued that creativity was just another name for problem solving. We now know they were wrong, because most successful creativity comes through the process that led to Instagram and Starbucks: you begin without yet knowing what the real problem is. The parameters aren't clearly specified, the goal isn't clear, and you don't even know what it would look like if you did solve the problem. It's not obvious how to apply your past experience solving other problems. And there are likely to be many different ways to approach a solution.

These grope-in-the-dark situations are the times you need creativity the most. And that's why successful creativity always starts with asking.

It's easy to see how business innovation is propelled by formulating the right question, staying open to new cues, and focusing on the right problem. But it turns out the same is true of world-class scientific creativity. “The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution,” Albert Einstein declared. “To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advances in science.”

Einstein loved metaphor. “For the detective the crime is given,” he concluded. “The scientist must commit his own crime as well as carry out the investigation.”

If the right “crime”—the right puzzle or question—is crucial for business and scientific breakthroughs, what about breakthroughs in art or poetry or music? A great painting doesn't emerge from posing a good question—does it?

The pioneering creativity researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Chik-sent-mee-hi), who was one of my mentors at the University of Chicago, decided to answer that question. He and a team of fellow psychologists from the University of Chicago spent a year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the top art schools in the United States. “How do creative works come into being?” they wanted to know. They set up an “experimental studio” in which they positioned two tables. One was empty, the other laden with a variety of objects, including a bunch of grapes, a steel gearshift, a velvet hat, a brass horn, an antique book, and a glass prism. They then recruited thirty-one student artists and instructed them to choose several items, position them any way they liked on the empty table, and draw the arrangement.

After observing the artists, Csikszentmihalyi was able to identify two distinct artistic approaches. One group took only a few minutes to select and pose the objects. They spent another couple of minutes sketching an overall composition and the rest of their time refining, shading, and adding details to the composition. Their approach was to formulate a visual problem quickly and then invest their effort in solving that problem.

The second group could not have been more different. These artists spent five or ten minutes examining the objects, turning them around to view them from all angles. After they made their choices, they often changed their mind, went back to the table, and replaced one object with another. They drew the arrangement for twenty or thirty minutes and then changed their mind again, rearranged the objects, and erased and completely redrew their sketch. After up to an hour like this, students in this group settled on an idea and finished the drawing in five or ten minutes. Unlike the first group—which spent most of the time solving a visual problem—this group was searching for a visual problem. The research team called this a “problem-finding” creative style.