Table of Contents

Related Titles

Title Page

Copyright

List of Abbreviations

List of Contributors

Chapter 1: History of Post-Polymerization Modification

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Post-Polymerization Modification via Thiol-ene Addition

1.3 Post-Polymerization Modification of Epoxides, Anhydrides, Oxazolines, and Isocyanates

1.4 Post-Polymerization Modification of Active Esters

1.5 Post-Polymerization Modification via Thiol-Disulfide Exchange

1.6 Post-Polymerization Modification via Diels-Alder Reactions

1.7 Post-Polymerization Modification via Michael-Type Addition

1.8 Post-Polymerization Modification via Azide Alkyne Cycloaddition Reactions

1.9 Post-Polymerization Modification of Ketones and Aldehydes

1.10 Post-Polymerization Modifications via Other Highly Efficient Reactions

1.11 Concluding Remarks

References

Chapter 2: Post-Polymerization Modifications Via Active Esters

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Active Esters in the Side Group

2.3 Star Polymers

2.4 Active Esters at the End Groups

2.5 Controlled Positioning of Active Ester Moieties

2.6 Summary

References

Chapter 3: Thiol–ene Based Functionalization of Polymers

3.1 Introduction

3.2 General Considerations and Mechanisms

3.3 Functionalization of Polymers

3.4 Summary

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 4: Thiol–yne Chemistry in Polymer and Materials Science

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The Thiol–yne Reaction in Small-Molecule Chemistry

4.3 The Thiol–yne Reaction in Polymer and Material Synthesis

References

Chapter 5: Design and Synthesis of Maleimide Group Containing Polymeric Materials via the Diels-Alder/Retro Diels-Alder Strategy

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Maleimide Functional Group Containing Polymeric Materials

5.3 The Diels-Alder/Retro Diels-Alder Cycloaddition-Cycloreversion Reactions

5.4 Application of Diels-Alder/Retro Diels-Alder Reaction to Synthesize Maleimide-Containing Polymers

5.5 Conclusions

References

Chapter 6: The Synthesis of End-Functional Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymers

6.1 Introduction

6.2 End-Functionalization Methods in General

6.3 Functionalization During Initiation

6.4 Functionalization After Propagation

6.5 Functionalization During Propagation

6.6 Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 7: Functional Polymers with Controlled Microstructure Based on Styrene and N-Substituted Maleimides

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Background on Radical Copolymerization of Styrene and Maleimides

7.3 Precise Incorporation of Maleimide Units on Polystyrene Backbone

7.4 Tuning a Simple Technique for the Preparation of Sequence-Controlled Polymers to the Elaboration of Functionalized Well-Defined Macromolecules

7.5 Summary and Outlook

References

Chapter 8: Temperature-Triggered Functionalization of Polymers

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Temperature-Triggered Alteration of Polymer Property

8.3 Temperature-Triggered Generation of Reactive Groups

8.4 Conclusions

References

Chapter 9: New Functional Polymers Using Host–Guest Chemistry

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Polymers with Responsive Three-Dimensional Structures

9.3 Polymer Probes for Specific Chemical Sensing

9.4 Responsive Soft Materials

9.5 Functional Polyrotaxanes

References

Chapter 10: Glycopolymers via Post-polymerization Modification Techniques

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Synthesis and Controlled Polymerization of Glycomonomers

10.3 Post-Polymerization Modification of Polymer Scaffolds to Synthesize Glycopolymers

10.4 Azide–Alkyne Click Reactions

10.5 Utilizing Thiol-Based Click Reactions

10.6 Thiol–ene Click Reactions

10.7 Thiol–yne Click Reactions

10.8 Thiol–Halogen Substitution Reactions

10.9 Alkyne/Alkene Glycosides: “Backward” Click Reactions

10.10 Post-Polymerization Glycosylation of Nonvinyl Backbone Polymers

10.11 Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 11: Design of Polyvalent Polymer Therapeutics

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Polyvalent Polymer Therapeutics

11.3 Conclusions

References

Chapter 12: Posttranslational Modification of Proteins Incorporating Nonnatural Amino Acids

12.1 Posttranslational Modification of Existing Amino Acids within Protein Chain

12.2 Exploiting Biosynthetic Machinery: Cotranslational Approach

12.3 Intein-Inspired Ligation Approach

12.4 Combined Approach

12.5 Protein and Polymer Conjugates

12.6 Modulating the Physicochemical Properties of Protein Polymers via NAA Incorporation

12.7 Future in Combined Technologies to Fabricate Tailored Protein-Polymer Conjugates as New Materials

12.8 Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

References

Chapter 13: Functionalization of Porous Polymers from High-Internal-Phase Emulsions and Their Applications

13.1 Introduction

13.2 Functionalization of PolyHIPEs

13.3 Applications

13.4 Conclusions

References

Chapter 14: Post-Polymerization Modification of Polymer Brushes

14.1 Introduction

14.2 Synthesis and Strategies for Functional Polymer Brushes

14.3 Applications of Polymer Brush Modification: Multifunctional Surfaces via Photopatterning

14.4 Conclusions and Future Outlook

References

Chapter 15: Covalent Layer-by-Layer Assembly Using Reactive Polymers

15.1 Introduction

15.2 Overview of Layer-by-Layer Assembly: Conventional versus Covalent Assembly

15.3 Scope and Organization

15.4 Covalent LbL Assembly Based on “Click Chemistry”

15.5 Reactive LbL Assembly Using Azlactone-Functionalized Polymers

15.6 Other Reactions and Other Approaches

15.7 Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

Index

Related Titles

Schlüter, D. A., Hawker, C., Sakamoto, J. (eds.)

Synthesis of Polymers

New Structures and Methods

2 Volumes 2012

ISBN: 978-3-527-32757-7

Mittal, V. (ed.)

In-situ Synthesis of Polymer Nanocomposites

2012

ISBN: 978-3-527-32879-6

Friedrich, J.

The Plasma Chemistry of Polymer Surfaces

2012

ISBN: 978-3-527-31853-7

Mathers, R. T., Meier, M. A. R. (eds.)

Green Polymerization Methods

Renewable Starting Materials, Catalysis and Waste Reduction

2011

ISBN: 978-3-527-32625-9

Barner-Kowollik, C., Gruendling, T., Falkenhagen, J., Weidner, S. (eds.)

Mass Spectrometry in Polymer Chemistry

Advanced Techniques for Surface Design

2011

ISBN: 978-3-527-32924-3

Leclerc, M., Morin, J.-F. (eds.)

Design and Synthesis of Conjugated Polymers

2010

ISBN: 978-3-527-32474-3

Dubois, P., Coulembier, O., Raquez, J.-M. (eds.)

Handbook of Ring-Opening Polymerization

2009

ISBN: 978-3-527-31953-4

Barner-Kowollik, C. (ed.)

Handbook of RAFT Polymerization

2008

ISBN: 978-3-527-31924-4

Coqueret, X., Defoort, B. (eds.)

High Energy Crosslinking Polymerization

Applications of Ionizing Radiation

2006

ISBN: 978-3-527-31838-4

The Editor

Prof. Dr. Patrick Theato

Techn. & Macromol. Chemistry

Bundesstraße 45

20146 Hamburg

Germany

Prof. Dr. Harm-Anton Klok

EPFL, Lab. des Polymères

STI-IMX-LP, MXD 112

Station 12

1015 Lausanne

Switzerland

All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and publisher do not warrant the information contained in these books, including this book, to be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in mind that statements, data, illustrations, procedural details or other items may inadvertently be inaccurate.

Library of Congress Card No.: applied for

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <http://dnb.d-nb.de>.

© 2013 Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany

All rights reserved (including those of translation into other languages). No part of this book may be reproduced in any form — by photoprinting, microfilm, or any other means — nor transmitted or translated into a machine language without written permission from the publishers. Registered names, trademarks, etc. used in this book, even when not specifically marked as such, are not to be considered unprotected by law.

Print ISBN: 978-3-527-33115-4

ePDF ISBN: 978-3-527-65545-8

ePub ISBN: 978-3-527-65544-1

mobi ISBN: 978-3-527-65543-4

oBook ISBN: 978-3-527-65542-7

List of Abbreviations

| 2Box | 2-(3-Butenyl)-2-oxazoline |

| 2EOx | 2-Ethyl-2-oxazoline |

| 2MOx | 2-Methyl-2-oxazoline |

| αAl ∈ CL | 6-Allyl-∈-caprolactone |

| αCl ∈ CL | α-Chloro-∈-caprolactone |

| α-GP-alkyne | 2-(α-D-Glucopyranosyloxy)-N-2-propyn-1-yl acetamide |

| αN3 ∈ CL | α-Azido-∈-caprolactone |

| αP ∈ CL | α-Propargyl-∈-caprolactone |

| αPδVL | α-Propargyl-δ-valerolactone |

| ∈ CL | ∈-caprolactone |

| γA ε CL | γ-Acryloyloxy-ε-caprolactone |

| AAm | Acrylamide |

| AARS | Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase |

| AC | Acryloyl carbonate |

| ADC | 2,6-Anthracenedicarboxylate |

| ADTC | 2,2-Bis(azidomethyl)trimethylene carbonate |

| AGE | Allyl glycidyl ether |

| Aha | Azidohomoalanine |

| AHMA | 6-Azidohexyl methacrylate |

| AIBN | 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) |

| AMA | Anthrylmethyl methacrylate |

| Amp | Ampicillin |

| AN | Acrylonitrile |

| AOA | Acetone oxime acrylate |

| AOI | 2-(Acryloyloxy)ethylisocyanate |

| AP | Anionic polymerization |

| APMOS | Anthracen-9-ylmethyl 2-((2-bromo-2-methyl-propanoyloxy)methyl)-2-methyl-3-oxo-3-(prop-2-ynyloxy)-propyl succinate |

| AROP | Anionic ring-opening polymerization |

| ATRA | Atom transfer radical addition |

| ATRP | Atom transfer radical polymerization |

| AzDXO | 5,5-Bis(azidomethyl)-1,3-dioxan-2-one |

| AzEMA | 2-Azidoethyl methacrylate |

| AzHMA | 6-Azidohexyl methacrylate |

| AzPMA | 3-Azidopropyl methacrylate |

| B3MA | But-3-enyl methacrylate |

| BMVB | 1-[(3-Butenyloxy)methyl]-4-vinylbenzene |

| BP2TF | Benzyl pyridine-2-yldithioformate |

| Bpa | p-Benzoylphenylalanine |

| BPNorb | 3-(Bromo)propyl exo-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-carboxylate |

| bPP | Brominated p-phenylene |

| BrS | 4-Bromostyrene |

| Bu | Butadiene |

| CAA | Chloroallyl azide |

| CAT | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase |

| CD | Cyclodextrin |

| CHMFS | 4-(6′-Methylcyclohex-3-′enylmethoxy)-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorostyrene |

| Cm | Chloramphenicol |

| CROP | Cationic ring opening polymerization |

| CuAAC | Copper catalyzed azide/alkyne cycloaddition |

| D3 | Hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane |

| DAPA | N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-acrylamide |

| DBCO-NHS | Aza-dibenzocyclooctyne N-hydroxy succinimide ester |

| DBTDL | Dibutyltin dilaureate |

| DBU | 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene |

| DBz | β-Benzyl aspartate-ω-benzylamide |

| DEAEMA | 2-(Diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate |

| DecEnOx | 2-(Dec-9-enyl)-2-oxazoline |

| DHFR | Dihydrofolate reductase |

| DIC | Diisopropylcarbodiimide |

| DIEA | N,N-Diisopropylethylamine |

| DMAEMA | 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate |

| DMPA | 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone |

| dPGL | 3,6-Dipropargyl-1,4-dioxane-2,5-dione |

| DTC | 2,2-Bis(methyl)trimethylene carbonate |

| DVB | Divinylbenzene |

| EdMA | Ethylene dimethacrylate |

| EG | Ethylene glycol |

| EGMA | Ethylene glycol methacrylate |

| EPL | Expressed protein ligation |

| EO | Ethylene oxide |

| EOP | Ethylene/olefin copolymerization |

| ET | Ethylene terephthalate |

| EVGE | Ethoxy vinyl glycidyl ether |

| FMA | Furfuryl methacrylate |

| FRP | Free radical polymerization |

| Fu-PU | Furan containing polyurethanes |

| FVFC | 2-Formal-4-vinylphenyl ferrocenecarboxylate |

| GA | Glycidyl acrylate |

| GalNac | N-Acetylgalactosamine |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GI | Globalide |

| GlcAc4-SH | 2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-D-glucopyranose |

| GlcNAc | N-acetylglucosamine |

| GMA | Glycidyl methacrylate |

| GPE | Glycidyl phenyl ether |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| HB-I (PPV-PPE) | Hyperbranched iodinated poly(phenylene vinylene-phenylene ethynylene) |

| HMPA | Hexamethylphosphoramide |

| Hpg | Homopropargylglycine |

| HPMA | N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide |

| IBBL | 2,8-Dioxa-1-isopropenylbicyclo[3.3.0]octane-3,7-dione |

| IMK | Isopropenyl methyl ketone |

| LA | L-lactide |

| LCST | Lower critical solution temperature |

| MA | Methyl acrylate |

| MAA | Methacrylic acid |

| MAC | 5-Methyl-5-allyoxycarbonyl-1,3-dioxanone |

| MAC2AE | N-methacryloyl-β-alanine [N′]–oxysuccinimide ester |

| MAn | Maleic anhydride |

| MAPTT | 3-(3-Methacrylamidopropanoyl)-thiazolidine-2-thione |

| MBPS-A | Polystyrene-anthracene multiblock copolymer |

| ME6TREN | Tris[2-(dimethylamino)-ethyl]amine |

| MI | Maleimide |

| MMA | Methyl methacrylate |

| MVI | 1-Methylvinylisocycanate |

| N3MPA | 2-[(2-Deoxy-2-azido-α-D-mannopyranosyloxy)ethanamido]-ethyl acrylamide |

| Naasc | Sodium ascorbate |

| NAA | Non-natural amino acid |

| nAChR | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

| NAS | N-acryloxysuccinimide |

| nBA | N-butyl acrylate |

| NBAz | 2-(Norborn-2-en-5-yl)-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxazoline |

| NCL | Native chemical ligation |

| NHNS | Bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-exo-2-carboxylic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester |

| NMAS | N-methacryloxysuccinimide |

| NMM | 4-Methylmorpholine |

| NMP | Nitroxide-mediated polymerization |

| NNC | 4-Nitro-1-naphthyl cinnamate |

| NPA | p-Nitrophenyl acrylate |

| NPC | 4-Nitrophenyl cinnamate |

| NPMA | p-Nitrophenyl methacrylate |

| NPME | 5-Norbornene-2-methyl-propargyl ether |

| NSVB | N-oxysuccinimide p-vinyl benzoate |

| OBNorb | 3-Oxobutyl exo-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-carboxylate |

| OEGMA | Oligo(ethylene glycol methacrylate) |

| OP | Oxidative polymerization |

| p-AcF | p-Acetylphenylalanine |

| p-AzF | p-Azidophenylalanine |

| p-FF | p-Fluorophenylalanine |

| p-NH2F | p-Aminophenylalanine |

| PA | Polyaddition |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PC | Polycondensation |

| PCDO | 5-Methyl-5-propargyloxycarbonyl-1,3-dioxan-2-one |

| PDA | 2-(Pyridyldithio)-ethylamine |

| PDS | Pyridyl disulfide |

| PDSA | Pyridyl disulfide propyl acrylate |

| PDSM | Pyridyl disulfide ethyl methacrylate |

| PDTEMA | N-[2-(2-pyridyldithio)]ethyl methacrylamide |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PFA | Pentafluorophenyl acrylate |

| PFMA | Pentafluorophenyl methacrylate |

| PFPNorb | exo-5-Norbornene-2-carboxylic acid pentafluorophenyl ester |

| PFS | Pentafluorostyrene |

| PFVB | Pentafluorophenyl 4-vinyl benzoate |

| PGL | 3-Methyl-6-propargyl-1,4-dioxane-2,5-dione |

| PgMA | Propargyl methacrylate |

| PKE | Poly(keto ester) |

| PLG | γ-Propargyl-L-glutamate |

| PMDETA | N,N,[N′],[N′],[N]′′-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine |

| PMNorb | 3-(Maleimidyl)propyl exo-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-carboxylate |

| PP | Photopolymerization |

| PPh | p-Phenylene |

| PPP | Pulsed-plasma polymerization |

| ProDOT-H | 3,3-dihexyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-thieno[3,4-b][1,4]dioxepine |

| ProDOT-P | 3-methyl-3-((prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)methyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-thieno[3,4-b][1,4]dioxepine |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PTM | Posttranslational modification |

| PTSA | p-Toluene sulfonic acid |

| PTXL | Paclitaxel |

| PU(ArAll3-HMDI) | 2,3,4-Tri-O-allyl-L-arabinitol based polyurethane |

| PU-DPPD | 2,2-Di(prop-2-ynyl)propane-1,3-diol based polyurethane |

| PU-MPPD | 2-Methyl-2-propargyl-1,3-propanediol based polyurethane |

| PU-PBM | 3,5-Bis(hydroxymethyl)-1-propargyloxybenzene based polyurethane |

| Py | Pyridine |

| PynOx | 2-(Pent-4-ynyl)-2-oxazoline |

| RAFT | Reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer |

| ROMP | Ring-opening metathesis polymerization |

| ROP | Ring-opening polymerization |

| RSI | Residue-specific incorporation |

| SAE | Succinic acid ester |

| SCEMA | 2-(N-succinimidylcarboxyoxy)ethyl methacrylate |

| SI | Surface-initiated |

| SMANCS | Styrene-alt-maleic anhydride copolymer conjugated neocarzinostatin |

| SPAAC | Strain promoted azide/alkyne cycloaddition |

| SSI | Site-specific incorporation |

| St | Styrene |

| t-BA | t-Butyl acrylate |

| TCEP | Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TFPMA | Tetrafluorophenyl methacrylate |

| TMC | Trimethylene carbonate |

| TMI | m-Isopropenyl-α-α-dimethylbenzyl isocyanate |

| TMS | Trimethylsilyl |

| ttHA | trans,trans-Hexa-2,4-dienylacrylate |

| V1D2 | 1-Vinyl-1,3,3,5,5-pentamethylcyclotrisiloxane |

| V4 | 1,3,5,7-Tetramethyl-1,3,5,7-tetravinylcyclotetrasiloxane |

| VBA | Vinylbenzaldehyde |

| VDF | Vinyldiene fluoride |

| VDM | 2-Vinyl-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxazoline |

| VI | Vinylisocyanate |

| VMK | Vinylmethylketone |

| VP | Vinyl pyridine |

| VSC | Vinyl sulfone carbonate |

List of Contributors

ois Lutz

ois LutzChapter 1

History of Post-Polymerization Modification

The history of post-polymerization modification, also known as polymer analogous modification, is arguably as long as the history of polymer science. As early as 1840, Hancock and Ludersdorf independently reported the transformation of natural rubber into a tough and elastic material on treatment with sulfur [1]. In 1847, Schönbein exposed cellulose to nitric acid and obtained nitrocellulose [2], which was later employed as an explosive. In 1865, Schützenberger prepared cellulose acetate by heating cellulose in a sealed tube with acetic anhydride. The resulting material has found widespread use as photographic film, artificial silk, and membrane material, among others [3]. Although the post-polymerization modification of these natural polymers was widely used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the nature of these materials and their modification reactions were only poorly understood. This comes as no surprise, as it was at the same time that Staudinger [4], one of the pioneers of modern polymer science, was struggling to gain acceptance for the notion of the existence of macromolecules. Staudinger [5] also coined the term polymer analogous reaction and studied these reactions as an attractive approach to fabricate functional materials.

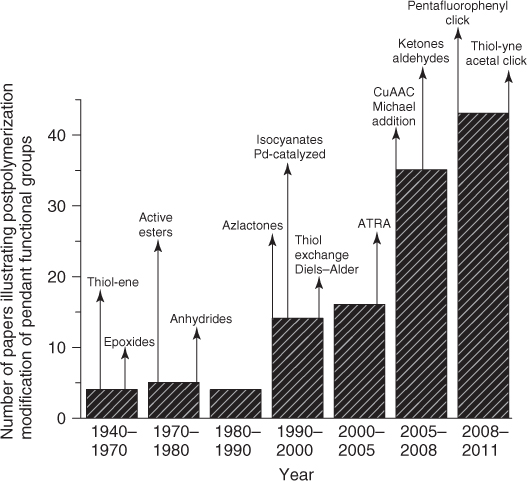

The general acceptance of the concept of macromolecules also marked the beginning of an increased use of post-polymerization modification reactions to engineer synthetic polymers. Serniuk et al. [6] reported the functionalization of butadiene polymers with aliphatic thiols via thiol–ene addition in 1948. Chlorinated polystyrene–divinylbenzene beads were first used in the 1950s as ion exchange resins [7] and later by Merrifield to develop solid-state peptide synthesis [8]. The modification of halogenated or lithiated poly(meth)acrylates was first investigated in the early 1960s [9, 10] and followed by Iwakura's studies on the post-polymerization modification of polymers bearing pendant epoxide groups [11–13]. Although many of the early developments in polymer science can be attributed to the utilization of post-polymerization modifications, the variety of chemical reactions that was available for post-polymerization modification was relatively limited (Figure 1.1). This, however, rapidly changed in the early 1990s with the emergence of living/controlled radical polymerization techniques such as atom-transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT), and nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP) [14–16]. The improved functional group tolerance of these methods as compared to conventional polymerization techniques allowed the fabrication of well-defined polymers bearing a wide variety of functional groups that can be quantitatively and selectively modified using relatively mild conditions without any side reactions.

Figure 1.1 Historical overview of the development of post-polymerization modification. The work on post-polymerization modification increased with a skyrocketing pace starting from the late 1990s as a result of development of functional-group-tolerant (controlled radical) polymerization techniques combined with the (re)discovery of highly efficient coupling chemistries. This figure was prepared based on the articles cited in this chapter and last updated in September 2011.

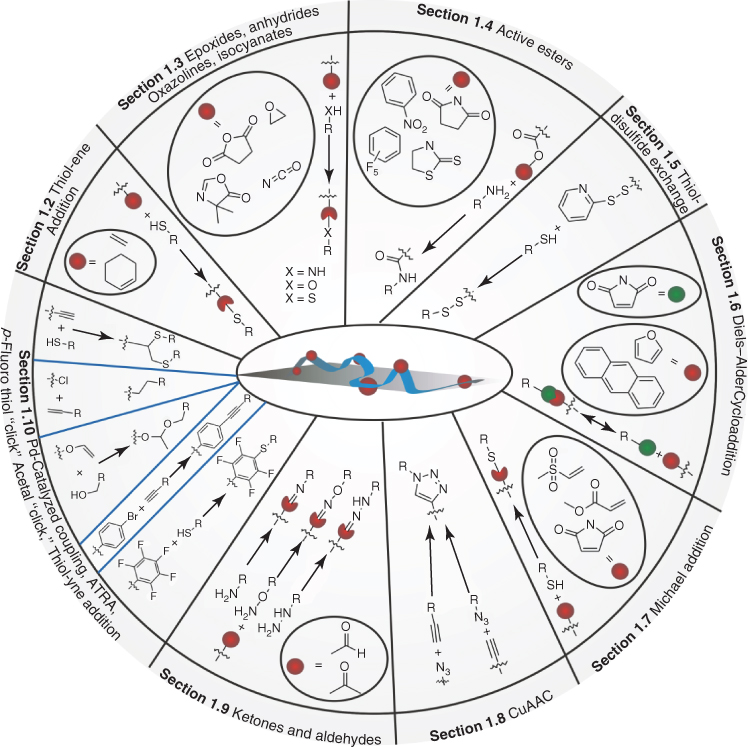

The emergence of living/controlled radical polymerization techniques coincided with the discovery/revival of several chemoselective coupling reactions such as copper-catalyzed azide/alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), thiol–ene addition, and many others, which are now commonly referred to as click reactions. Together, these two developments provided the basis for the explosive growth in use and versatility of post-polymerization reactions since the 1990s. The aim of this chapter is to give a historical account of the development of nine main classes of post-polymerization modification reactions (Scheme 1.1). For the selection of these reactions, strategies that involve the use of, for example, poorly controlled nucleophilic substitution reactions and the modification of relatively inert groups, such as alcohols and carboxylic acids, were not considered. Instead, emphasis was placed on readily available reactive groups that do not require an additional deprotection step before post-polymerization modification.

Scheme 1.1 Nine different classes of reactions that can be used for the preparation of functionalized polymers via post-polymerization modification.

The anti-Markovnikov addition of thiols to alkenes is usually mediated by a radical source or by ultraviolet (UV) irradiation [17]. One of the earliest systematic studies regarding the post-polymerization modification of polyBu via radical thiol addition was reported by Serniuk and coworkers in 1948 [6]. They proposed that only the vinyl groups generated by 1,2-addition of butadiene units (i.e., pendant vinyl groups) were functionalized, which was later confirmed by Romani and coworkers [18]. Since these early studies, thiol–ene post-polymerization modification has developed into a powerful synthetic tool. Table 1.1 provides an overview of different alkene functional polymers that have been used as substrates for post-polymerization modification.

Table 1.1 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Via Radical Thiol Addition

A drawback of thiol–ene addition to poly(1,2-Bu) is that because of the close proximity of the neighboring vinyl groups, the radical formed after the addition of the thiol may attack an adjacent vinyl group, leading to an intramolecular cyclization [20]. One possibility to suppress this side reaction is to carry out the post-polymerization modification at low temperature and at relatively high concentrations [24]. Schlaad and coworkers further illustrated that, by increasing the distance between pendant alkene groups, intramolecular cyclization could also be supressed, which revolutionized the via thiol–ene post-polymerization modification [22]. This was demonstrated by the post-polymerization modification of poly2Box, which was quantitatively modified using 1.2–1.5 equivalents thiol under mild conditions (radicals generated with UV light at room temperature).

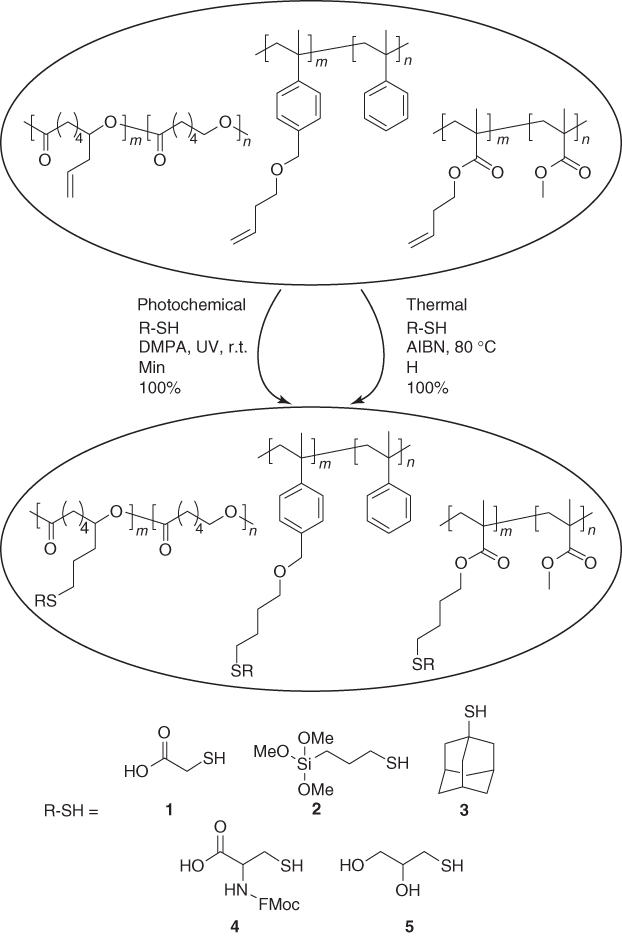

Radicals that mediate the thiol–ene addition can either be generated by thermal or photochemical initiation. Hawker and coworkers illustrated that, although both initiation pathways lead to the complete conversion of pendant alkenes, milder conditions and shorter reaction times are sufficient when photoinitators are used (Scheme 1.2) [23]. Furthermore, they also demonstrated the orthogonality of the radical thiol addition and CuAAC and the compatibility of the alkene group with controlled radical polymerization (CRP) techniques.

Scheme 1.2 Post-Polymerization modification of polymers bearing alkene groups via thiol–ene addition either mediated by photochemical or thermal initiation [23].

Recently, Heise reported the preparation of an unsaturated polyester (polyGI) via enzymatic ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of the corresponding cyclic ester monomer containing backbone alkene groups. He demonstrated that these backbone alkene groups are also susceptible to post-polymerization modification via thiol–ene addition, but near-quantitative conversion of these groups is only possible when a high excess of thiol is used, as these backbone alkene groups have decreased reactivity compared to pendant alkenes [31].

Epoxides, anhydrides, oxazolines, and isocyanates represent a class of reactive groups that have a relatively long history in polymer science. A common feature of these groups is that they are tolerant toward radical-based polymerization techniques, which explains why polymers containing these groups were extensively used for the fabrication of functional polymers via post-polymerization modification already since the 1960/1970s. Table 1.2 provides an overview of polymers bearing epoxide, anhydride, oxazoline, and isocyanate groups that have been used for post-polymerization modification.

Table 1.2 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Bearing Epoxide, Anhydride, Oxazoline, and Isocyanate Groups

Although thermosetting epoxy resins were already being used in the 1950s for many applications such as tissue embedding for electron microscopy [56] or as dental restoratives [57], it was only in the 1960s that Iwakura and coworkers for the first time systematically studied the post-polymerization modification of polymers containing epoxide groups, such as polyGA and polyGMA. They reported that the post-polymerization modification of polyGA or polyGMA with simple secondary amines (1.0–4.0 equivalents of amine) proceeded with low to moderate yields [11–13]. In 1974, Kalal [33] illustrated that the post-polymerization modification via epoxide ring opening can be catalyzed by a tertiary amine (TEA) and reported up to 80% conversion of epoxide groups of polyGMA with carboxylic acids in the presence of TEA. More recently, Barbey and Klok [37] exploited the catalytic effect of the TEA groups on epoxide ring opening by preparing polyGMA-co-polyDMAEMA brushes, which contained pendant TEA groups that were demonstrated to accelerate the rate of post-polymerization modification via epoxide ring opening with amines in aqueous media at room temperature. A drawback of epoxide-functionalized polymers is that they are prone to cross-linking on modification with primary amines because of the reaction between the secondary amines formed after the epoxide ring opening with another unreacted epoxide group [36]. While amines are most frequently employed for the post-polymerization modification of polymers bearing epoxide groups, epoxide groups themselves are reactive toward, for example, alcohols and carboxylic acids [33, 35].

Maleic anhydride (MAn) copolymers have attracted significant attention since the late 1970s and early 1980s with the work carried out by Maeda and coworkers [38, 39], who prepared the anticancer agent poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) conjugated neocarzinostatin (SMANCS). Functionalization of MAn copolymers with undemanding primary amines was reported to proceed almost quantitatively at ambient temperatures [40, 42, 43], whereas N-substituted maleimide (MI) formation was observed at elevated temperatures on ring closure of the maleamic acid (i.e., amine-modified MAn) [58, 59].

Polymers bearing pendant oxazoline groups can be prepared by the polymerization of 2-vinyl-4,4-dimethyl-5-oxazoline (VDM), which was first illustrated by Taylor and coworkers in the early 1970s [60]. Similar to MAn copolymers, quantitative modification of polyVDM with amines is possible at room temperature [47, 48]. Furthermore, the hydrolytic stability of the oxazoline group allows aqueous post-polymerization modification without side reactions [46]. For instance, this selectivity toward amines in aqueous media was utilized for rapid and high-density immobilization of protein A onto polyVDM-functionalized beads at pH 7.5 [61].

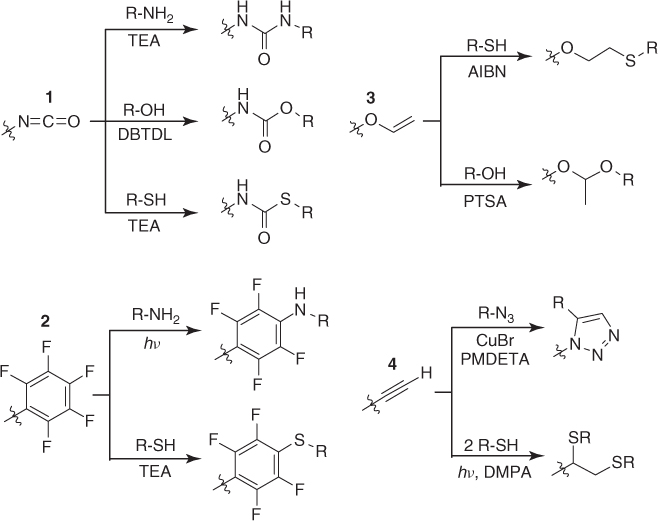

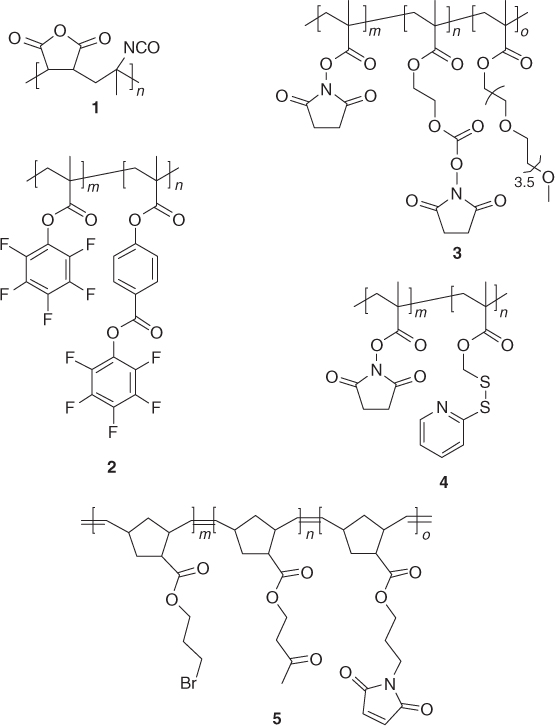

The isocyanate group is another attractive handle that allows post-polymerization modification with amines, alcohols, and thiols. While the modification of isocyanates with amines or thiols proceeds rapidly and quantitatively and can be further facilitated by the addition of TEA or 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU), quantitative conversion with alcohols is only possible in the presence of a catalyst such as dibutyltin dilaureate (DBTDL) (1 in Scheme 1.3) [51, 54]. m-Isopropenyl-α-α-dimethylbenzyl isocyanate (TMI), vinylisocyanate (VI), and 1-methylvinylisocycanate (MVI) are examples of commonly employed monomers for the synthesis of isocyanate-containing (co)polymers (Table 1.2). A special feature of these isocyanate monomers, which they share with MAn, is that their homopolymerization is more demanding compared to their copolymerization. While the homopolymerization of VI by conventional polymerization techniques can be accompanied by a variety of side reactions because of the competing reactivity of the vinyl double bond and isocyanate group [62], TMI homopolymerization does not yield high-molecular-weight polymer because of the steric hinderance imposed by the α-methyl group to the radical propagation site [63, 64]. Beyer and coworkers [51] synthesized MVI-alt-MAn, in which the isocyanate and anhydride groups were sequentially modified with an alcohol and amine, respectively (1 in Scheme 1.4). More recently, Flores et al. reported that a novel isocyanate-containing monomer (2-(acryloyloxy)ethylisocyanate, AOI) can be readily homopolymerized via RAFT polymerization [54] unlike VI, TMI, and MI, and Hensarling and coworkers [55] demonstrated the quantitative modification of polyAOI with thiols within minutes at room temperature.

Scheme 1.3 Polymers bearing isocyanate, n-alkyl pentafluorophenyl, allyl ether, and alkyne groups that can be quantitatively modified with various reagents, but under different reaction conditions [28, 51, 54, 65, 66].

Scheme 1.4 Polymers bearing multiple orthogonal and chemoselective handles that allow either sequential or one-pot post-polymerization modification with different functional groups [51, 67–70].

The synthesis and post-polymerization modification of active ester polymers was pioneered by Ferruti and Ringsdorf in the 1970s [71, 72]. Since then, a broad variety of active ester polymers has been developed utilizing essentially the complete spectrum of available polymerization techniques (Table 1.3). The reaction of active ester polymers with amines is probably the most frequently used post-polymerization modification strategy. Amines are most often used for the post-polymerization modification of active ester polymers since they can react selectively even in the presence of weaker nucleophiles, such as alcohols.

Table 1.3 Postpoymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Bearing Active Ester Groups

The most frequently employed active ester polymers are N-hydroxysuccinimide derivatives (NHS), such as polyNAS and polyNMAS. A drawback of these polymers, however, is that their solubility is limited to DMF and DMSO. Furthermore, the post-polymerization modification of these active ester polymers can be accompanied by side reactions, such as succinimide ring-opening or the formation of N-substituted glutarimide groups [95]. These side reactions can be suppressed by using an excess of amine or proton acceptor, such as TEA or DMAP [96].

Polymers bearing pentafluorophenyl (PFP) ester groups are attractive alternatives to NHS ester polymers, as polyPFMA was demonstrated to have higher reactivity and better hydrolytic stability and is soluble in a wide range of solvents as compared to polyNMAS [86]. Nevertheless, similar to NHS, PFP ester homopolymers are insoluble in water and thus cannot be functionalized in aqueous media.

Another class of active ester polymers that form an interesting alternative to polyNAS and polyNMAS are those that contain thiazolidine-2-thione (TT) groups. Subr and Ulbrich [91] reported that polymers bearing TT groups allow rapid aminolysis in aqueous media while displaying good hydrolytic stability. The difference between the rates of aminolysis and hydrolysis was found to be greatest between pH 7.4 and 8.0. A drawback of TT esters is that they display low selectivity between amines and thiols under identical reaction conditions.

Active ester polymers based on 4-vinyl benzoate (VB) often exhibit higher reactivity compared to their (meth)acrylates. For instance, Hawker et al. [73] used polyNSVB to fabricate dendrimer-functionalized polymers with high yields. Theato and Nilles [90] illustrated that, unlike polyPFMA and polyPFA, polyPFVB can quantitatively react with less nucleophilic aromatic amines. In a subsequent study, the same authors prepared statistical and block copolymers from pentafluorophenyl 4-vinyl benzoate (PFVB) and pentafluorophenyl methacrylate (PFMA) and demonstrated that these polymers could be sequentially modified with an aromatic and aliphatic amine, respectively (2 in Scheme 1.4) [67].

An alternative strategy toward orthogonally functionalizable active ester-based polymers was developed by Sanyal and coworkers [68]. These authors prepared copolymers of N-methacryloxysuccinimide (NMAS) with PEGMA and the carbonate functional monomer 2-(N-succinimidylcarboxyoxy)ethyl methacrylate (SCEMA) (3 in Scheme 1.4). Exposure of this copolymer to allylamine in THF at room temperature led to complete conversion of the carbonate groups with near-quantitative preservation of the active ester moieties, which could be subsequently modified by adding an excess of propargylamine at 50 °C.

Thiol–disulfide exchange is ubiquitous in biology where it is involved in a variety of processes such as modulation of enzyme activity [97], viral entry [98], and protein folding [99]. Although this reaction has been known since the 1920s from a study of Lecher on alkalisulfides/alkalithiols [100] as well as from the work of Hopkins on the biochemistry of glutathione [101], it was not until the late 1990s that Wang and coworkers first demonstrated that polymers bearing pyridyl disulfide groups could be employed as an appealing platform for post-polymerization modification via thiol–disulfide exchange, as it could proceed quantitatively and selectively in mild conditions and in aqueous media below pH 8 [102]. Table 1.4 gives an overview of various pyridyl disulfide-containing polymers that have been used as substrates for post-polymerization modification.

Table 1.4 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Via Thiol–Disulfide Exchange

Thiol–disulfide exchange post-polymerization modification is strongly pH dependent. There are opposing claims, however, regarding the optimum pH for quantitative functionalization. While Wang and coworkers [102] first illustrated that the rate of post-polymerization modification was highest between pH 8 and 10, Bulmus et al. [103] later reported higher conversions of pyridyl disulfide groups with terminal cysteine residues at pH 6 compared to pH 10.

One of the assets of the thiol–disulfide exchange reaction is that it allows the introduction of functional groups via a disulfide bond that is reversible and can be cleaved, either via reduction or with an exchange with another thiol. For instance, Langer [104] first demonstrated the reduction of pyridyl disulfide-containing poly(β-amino ester)s modified with glutathione in intracellular media, which led to a 50% decrease in the DNA binding capacity of the polymer. Ghosh et al. [69] later illustrated the quantitative release of incorporated thiols from the polymer backbone on reduction of the newly formed disulfide bonds by DTT. Furthermore, they also illustrated the orthogonality of thiol–disulfide exchange and aminolysis of active esters (4 in Scheme 1.4).

The cycloaddition reaction between a diene and a substituted alkene (dienophile), which was discovered in 1928 by Diels and Alder and distinguished with a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1950 [106], emerged as an attractive tool for post-polymerization modification in the 1990s [107, 108]. The Diels–Alder reaction fulfills the “click” criteria [109], as it can proceed with quantitative yields without any side reactions, is tolerant to a wide variety of functional groups, and is orthogonal with many other chemistries, such as CuAAC [110, 111]. Furthermore, many Diels–Alder reactions are reversible and the Diels–Alder adduct can decompose into the starting diene and dienophile at higher temperatures as compared to the temperature required for the forward reaction [112]. The reversibility of the Diels–Alder reaction has been extensively utilized to prepare thermoresponsive macromolecular architectures such as gels [107, 113–116], as well as in the synthesis of dendrimers [117] and smart copolymers [118].

Polymers that can be postmodified using Diels–Alder chemistry can be prepared either via a precursor route based on the deprotection of masked MI groups following polymerization of the corresponding monomers [116, 119] or by direct polymerization of the monomers containing unmasked dienes, such as furan or anthracene groups (Table 1.5). In an early example, Laita and coworkers demonstrated the post-polymerization modification of various furan-containing polyurethanes in which the furan group was either incorporated in the backbone or in the side chain of these polymers. While modification of the pendant furans with MIs proceeded to completion, conversion of backbone furan groups was limited to 30–60% at 40 °C using 3.0 equivalents of MI [120]. Jones et al. [114] later reported higher conversions (60–85%) of the post-polymerization modification of backbone anthracene groups with MIs in stoichiometric conditions when the reaction temperature was increased to 120 °C. Kim and coworkers [121] prepared copolymers bearing pendant anthracene groups, which were quantitatively modified with relatively bulky MI-functionalized chromophores at 120 °C by using stoichiometric amount of MI.

Table 1.5 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Via Diels–Alder Reactions

Another interesting class of functional groups for the Diels–Alder post-polymerization modification is pyridinedithioesters. These are attractive since they can act both as a chain transfer agent in RAFT polymerization [124] as well as a heterodienophile in [4 + 2] cycloaddition [125, 126]. Bousquet and coworkers [123] exploited this unique feature to quantitatively modify polyttHA at 50 °C by using 4.0–5.0 equivalents of polytBA (Mn = 3500–13500 g/mol), which was prepared by RAFT polymerization by using benzyl pyridine-2-yl dithioformate as a chain transfer agent.

Michael-type addition reactions have been frequently employed in polymer science starting from the early 1970s to fabricate a variety of macromolecular architectures including step-growth polymers, dendrimers, and cross-linked networks [127]. However, it is only more recently that this reaction has found use in preparing side-chain functional polymers, as only CRP techniques enable the preparation of polymers bearing Michael acceptors, such as acrylates, MIs, and vinyl sulfones. Table 1.6 gives an overview of different polymers that have been used in Michael-type post-polymerization modification. Post-polymerization modification of these polymers with thiols is particularly attractive, as this reaction can proceed quantitatively and selectively in aqueous media at room temperature [128].

Table 1.6 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Via Michael-Type Addition

Jérôme and coworkers [129] first demonstrated the synthesis of acrylate-bearing polyesters via ROP. Quantitative functionalization of these polymers without any backbone degradation was achieved in the presence of a large excess of thiol and pyridine (10.0–25.0 equivalents) at room temperature. Weck and coworkers showed that unmasked MI groups are compatible with ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) conditions. Quantitative modification of MI-bearing poly(norbornene)-based terpolymers was achieved when 2.0 equivalents of the thiol was used at 25 °C. Furthermore, these authors also demonstrated that Michael-type addition, CuAAC, and hydrazone formation are orthogonal chemistries that allow both sequential as well as one-pot modification with different functionalities (5 in Scheme 1.4) [70]. Polyesters bearing α,β unsaturated ketone groups have recently been prepared by the copolymerization of glycidyl phenyl ether and bicyclic bis(δ-butyrolactone) monomers by Ohsawa and coworkers. These polyesters contain pendant isopropenyl groups that were shown to react quantitatively with thiols in stoichiometric conditions when AlCl3 was used as a catalyst at room temperature [131]. Wang et al. prepared vinyl sulfone-functionalized poly(ester carbonate)s by ring-opening copolymerization of a vinyl sulfone carbonate monomer with ε-caprolactone, L-lactone, or trimethylene carbonate. Post-polymerization modification was reported to proceed quantitatively even with bulky thiols (2.0 equivalents of the thiol used) at room temperature [132].

The discovery that the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction between azides and alkynes can be carried out at mild conditions and in regioselective manner when Cu(I) salts are used as catalyst can be considered as the origin of what is now commonly referred to as click chemistry. As already predicted by Sharpless and Meldal in 2002 [133, 134], the scope of the CuAAC reaction turned out to be enormous. CuAAC often proceeds with quantitative yields both in aqueous and organic media under mild conditions and is orthogonal with almost any type of functionalization strategy. Table 1.7 gives an overview of azide- and alkyne-functionalized polymers that have been postmodified using CuAAC.

Table 1.7 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Via Azide/Alkyne Cycloaddition Reactions

In 2004, Binder reported that the ROMP of oxynorbonenes bearing unmasked alkyne groups proceeds with poor control owing to the competing reactivity of the alkyne group with the ROMP catalyst. This problem was circumvented by preparing alkyne-bearing polymers via a precursor route that involves side-chain modification of a precursor poly(norbornene) via alkylation with propargy bromide. These authors also prepared azide-bearing poly(oxynorbonene)s via another precursor route based on the modification of pendant alkyl bromide chains with sodium azide [158]. In 2005, Parrish and coworkers first demonstrated the compatibility of the alkyne groups with ROP by copolymerizing αPδVL with ε-caprolactone. Quantitative modification of the alkyne groups was achieved with an azide-functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) (Mn = 1100 g mol−1) in stoichiometric conditions at 80 °C when CuSO4 · 5H2O/Naasc was used as catalyst [143]. Matyjaszewski illustrated that, while an azide-containing monomer (3-azidopropyl methacrylate, AzPMA) can be successfully polymerized with ATRP, polymerization of propargyl methacrylate proceeded with poor control presumably owing to the side reactions involving the pendant acetylene group. Modification of polyAzPMA proceeded quantitatively with a library of alkynes (1.1 equivalents of the alkynes used) at room temperature in the presence of CuBr [135]. Riva and coworkers reported the compatibility of the azide groups with ROP by preparing copolymers of an azide-functionalized caprolactone (αN3 ε CL) with ε-caprolactone, which reacts quantitatively with propargyl benzoate (1.2 equivalents) at 35 °C when CuI was used [136]. The possibility to synthesize azide-/alkyne-functionalized polymers via direct polymerization of the corresponding monomers, as demonstrated in these last three examples, marked the beginning of an explosive growth of the use of CuAAC post-polymerization modification strategy (Table 1.7).

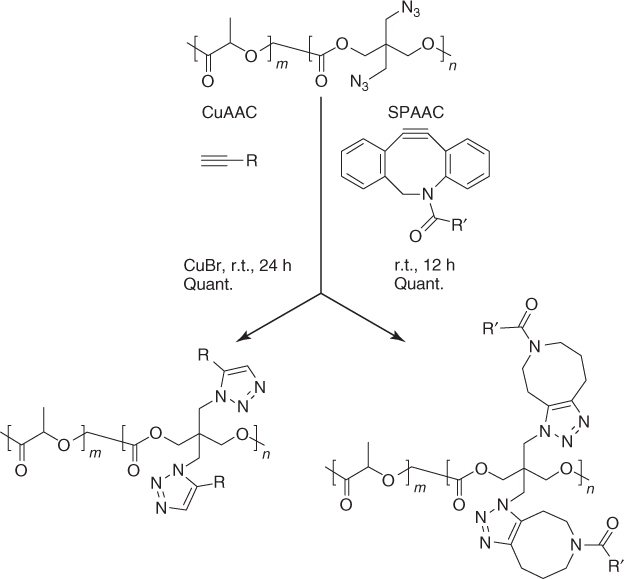

A drawback of the CuAAC post-polymerization modification reaction is that removal of the copper catalyst can be demanding, as it can form complexes with the triazole ring, which hampers the solubility of the functionalized polymer [137]. Furthermore, toxicity of the copper catalyst to cells limits the applicability of CuAAC reaction in biological media [159, 160]. An attractive, copper-free functionalization strategy is the strain-promoted azide alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction [161]. Recently, Song and coworkers [142] demonstrated that the functionalization of pendant azide groups of polyAzDXO via SPAAC reaches quantitative conversion at shorter reaction times compared to CuAAC and at lower equivalents of the cyclooctyne/alkyne used (Scheme 1.5).

Scheme 1.5 Post-Polymerization modification of polyAzDXO via CuAAC and SPAAC reaction [142].

Ketones and aldehydes can selectively react with primary amines, alkoxyamines, and hydrazines to form imines, oximes, and hydrazones, respectively. While imines are usually prone to hydrolysis, oximes and hydrazones are hydrolytically stable between slightly acidic to neutral pH [162, 163]. Nevertheless, imines can be further converted to stable secondary amines via reductive amination in the presence of a reducing agent, such as borohydride derivatives [164, 165]. Table 1.8 gives an overview of aldehyde and ketone functional polymers that have been modified via post-polymerization modification.

Table 1.8 Post-Polymerization Modification of (co)Polymers Bearing Ketone and Aldehyde Groups

Table 1.81.6