Table of Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Preface

Major Changes in the Fourth Edition

Acknowledgments

The Authors

CHAPTER 1: The Context of Health Care Financial Management

Changing Methods of Health Care Financing and Delivery

Addressing the High Cost of Care

Establishing Value-Based Purchasing

Summary

Key Terms

CHAPTER 2: Health Care Financial Statements

The Balance Sheet

The Statement of Operations

The Statement of Changes in Net Assets

The Statement of Cash Flows

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

Appendix A: Financial Statements for Sample Not-for-Profit and For-Profit Hospitals, and Notes to Financial Statements

CHAPTER 3: Principles and Practices of Health Care Accounting

The Books

An Example of the Effects of Cash Flows on Profit Reporting under Cash and Accrual Accounting

Recording Transactions

Developing the Financial Statements

Summary

Key Terms

CHAPTER 4: Financial Statement Analysis

Horizontal Analysis

Trend Analysis

Vertical (Common-Size) Analysis

Ratio Analysis

Liquidity Ratios

Revenue, Expense, and Profitability Ratios

Activity Ratios

Capital Structure Ratios

Summary

Key Equations

Key Terms

CHAPTER 5: Working Capital Management

Working Capital Cycle

Working Capital Management Strategies

Cash Management

Sources of Temporary Cash

Revenue Cycle Management

Collecting Cash Payments

Investing Cash on a Short-Term Basis

Forecasting Cash Surpluses and Deficits: The Cash Budget

Accounts Receivable Management

Methods to Monitor Revenue Cycle Performance

Fraud and Abuse

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

CHAPTER 6: The Time Value of Money

Future Value of a Dollar Invested Today

Present Value of an Amount to Be Received in the Future

Future and Present Values of Annuities

Future and Present Value Calculations and Excel Functions for Special Situations

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

Appendix B: Future and Present Value Tables

CHAPTER 7: The Investment Decision

Objectives of Capital Investment Analysis

Analytical Methods

Using an NPV Analysis for a Replacement Decision

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equation

Appendix C: Technical Concerns in Calculating Net Present Value

Appendix D: Adjustments for Net Working Capital

Appendix E: Tax Implications for For-Profit Entities in a Capital Budgeting Decision and the Adjustment for Interest Expense

Appendix F: Comprehensive Capital Budgeting Replacement Cost Example

CHAPTER 8: Capital Financing for Health Care Providers

Equity Financing

Debt Financing

Bond Issuance Process

Lease Financing

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

Appendix G: Bond Valuation, Loan Amortization, and Debt Borrowing Capacity

CHAPTER 9: Using Cost Information to Make Special Decisions

Break-Even Analysis

Product Margin

Applying the Product Margin Paradigm to Making Special Decisions

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

Appendix H: Break-even Analysis for Practice Acquisition

CHAPTER 10: Budgeting

The Planning-and-Control Cycle

Organizational Approaches to Budgeting

Types of Budgets

Monitoring Variances to Budget

Group Purchasing Organizations

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equation

Appendix I: An Extended Example of How to Develop a Budget

CHAPTER 11: Responsibility Accounting

Decentralization

Types of Responsibility Centers

Measuring the Performance of Responsibility Centers

Budget Variances

Summary

Key Terms

Key Equations

CHAPTER 12: Provider Cost-Finding Methods

Cost-to-Charge Ratio

Step-Down Method

Activity-Based Costing

Summary

Key Terms

CHAPTER 13: Provider Payment Systems

Evolution of the Payment System

Risk Sharing and the Principles of Insurance

Evolving Issues

Technology

Summary

Key Terms

Appendix J: Cost-Based Payment Systems

Glossary

Useful Websites and Apps

Websites

Health Policy APPs for iPad and iPhone from the Apple iTunes Store

Index

Cover design by Jeff Puda

Cover image : © imagewerks | Getty

Copyright © 2014 by William N. Zelman, Michael J. McCue, Noah D. Glick, and Marci S. Thomas. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Brand

One Montgomery Street, Suite 1200, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data

Zelman, William N., author.

Financial management of health care organizations : an introduction to fundamental tools, concepts, and applications / William N. Zelman, Michael J. McCue, Noah D. Glick, and Marci S. Thomas. – Fourth edition.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-46656-8 (cloth) – ISBN 978-1-118-46659-9 (pdf) – ISBN 978-1-118-46658-2 (epub)

I. McCue, Michael J. (Michael Joseph), 1954- author. II. Glick, Noah D., author. III. Thomas, Marci S., 1953- author. IV. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Health Facility Administration–economics. 2. Financial Management, Hospital–methods. 3. Practice Management, Medical–economics. WX 157]

RA971.3

362.1068'1–dc23

2013025598

To our families, for their love and patience

To our students and colleagues, for their invaluable insights and feedback

Preface

This book offers an introduction to the most used tools and techniques of health care financial management. It contains numerous examples from a variety of providers, including health maintenance organizations, hospitals, physician practices, home health agencies, nursing units, surgical centers, and integrated health care systems. The book avoids complicated formulas and uses numerous spreadsheet examples so that these examples can be adapted to problems in the workplace. For those desiring to go beyond the fundamentals, many chapters offer additional information in appendices. Each chapter begins with a detailed outline and concludes with a detailed summary, followed by a set of questions and problems. Answers to the questions and problems are available for download to instructors at www.josseybass.com/go/zelman4e. Finally, a number of perspectives are included in every chapter. Perspectives—examples from the real world—are intended to provide additional insight into a topic. In some cases these are abstracted from professional journals and in other cases they are statements from practitioners—in their own words.

The book begins with an overview in Chapter One of some of the key factors affecting the financial management of health care organizations in today's environment. Chapters Two, Three, and Four focus on the financial statements of health care organizations. Chapter Two presents an introduction to these financial statements. Financial statements are (perhaps along with the budget) the most important financial documents of a health care organization, and the bulk of this chapter is designed to help readers understand these statements, how they are created, and how they link together.

Chapter Three provides an introduction to health care financial accounting. This chapter focuses on the relationship between the actions of health care providers and administrators and the financial condition of the organization, examining how the numbers on the financial statements are derived, the distinction between cash and accrual bases of accounting—and the importance of defining what is actually meant by cost. By the time students complete Chapters Two and Three, they will have been introduced to a large portion of the terms used in health care financial management.

Building on Chapters Two and Three, Chapter Four focuses on interpreting the financial statements of health care organizations. Three approaches to analyzing statements are presented: horizontal, vertical, and ratio analysis. Great care has been taken to show how the ratios are computed and how to summarize the results.

Chapter Five focuses on the management of working capital: current assets and current liabilities. This chapter emphasizes the importance of cash management and provides many practical techniques for managing the inflows and outflows of funds through an organization, including managing the billing and collections cycle and paying off short-term liabilities.

Chapter Six introduces one of the most important concepts in long-term decision making—the time value of money. Chapter Seven builds on this concept, incorporating it into the investment decision by presenting several techniques for analyzing investment decisions: the payback method, net present value, and internal rate of return. Examples are given for both not-for-profit and for-profit organizations.

Once an investment has been decided on, it is important to determine how this asset will be financed, and this is the focus of Chapter Eight. Whereas Chapter Five deals with issues of short-term financing, Chapter Eight focuses on long-term financing, with a particular emphasis on issuing bonds.

Chapters Nine through Twelve introduce topics typically covered in a managerial accounting course. Chapter Nine focuses on the concept of cost and on using cost information—including fixed cost, variable cost, and break-even analysis—for short-term decision making. In addition to covering the key concepts, this chapter offers a set of rules to guide decision makers in making financial decisions. Chapter Ten explores budget models and the budgeting process. Several budget models are introduced, including program, performance, and zero-based budgeting. The chapter ends with an example of how to prepare each of the five main budgets: statistics budget, revenue budget, expense budget, cash budget, and capital budget. It also includes examples for various types of payors, including those with flat fee and capitation plans.

Chapter Eleven deals with responsibility accounting. It discusses the different types of responsibility centers and focuses on performance measurement in general and budget variance analysis in particular. Chapter Twelve discusses methods used by health care providers to determine their costs, primarily focusing on the step-down method and activity-based costing. This book concludes with Chapter Thirteen, “Provider Payment Systems.” This chapter, parts of which were combined with Chapter Twelve in the first edition, describes the evolution of the payment system in the United States, especially under health reform, as well as the specifics of various approaches to managing care and paying providers.

As noted below, the major changes from the third edition involve

Changes to Chapter One, the introductory chapter, provide an updated and current view of today's health care setting. Much has happened in the industry with the advent of value-based payment systems, population-based approaches to care, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Other new concepts include patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Enhancements include updated statistics in the chapter text and all the pertinent exhibits. All perspectives have been replaced with ones that look at more recent events.

Chapter Two has been updated to include recent changes in the literature issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). These changes address revenue recognition presentation of bad debt for many hospitals, increases in the level of charity care disclosure, and the guidance for self-insured risks. All perspectives and problems have been updated. There are also new key terms.

In Chapter Three, the perspectives have been replaced with four updated versions. Problems 11 through 20 have been changed and updated.

Chapter Four has been updated to include the latest hospital benchmark ratios from the 2013 Almanac of Hospital Financial and Operating Indicators (a reference work from Optum Inc.).

This chapter also addresses the change mentioned previously to the reporting of bad debt expense. All chapter problems have been updated as well. In addition, ratio problems 11 through 25 have been revised to provide a better picture of what each ratio analyzed means, beyond its being above or below the relevant benchmark.

Chapter Five has new sections on improving the revenue cycle management process and on fraud and abuse. All perspectives and problems have been revised and updated.

Chapter Six now includes perspectives illustrating time value of money concepts in use, as well as a new section that explains the effective rate function. In addition, all the problem sets have been updated.

Chapter Seven now offers an expanded discussion of how organizations measure the discount rate or cost of capital. This discussion also explains the weighted average cost of capital, which includes the cost of debt and the cost of equity. The key components of the capital asset pricing model, which is used to measure cost of equity, are presented as well. In addition, all perspectives have been updated, and problems have been changed and updated.

Chapter Eight now includes revisions to the explanation of interest rate swaps and a new section on bank qualified private placement loans. All the problems on lease financing and bond valuation have been revised and updated.

In Chapter Nine, the conceptual diagram and the related explanation for understanding breakeven have been substantially revised, and all perspectives have been replaced with updated versions. Most problems have updated figures, and three problems have been replaced with new ones. Also, a discussion of a new topic, physician practice valuation as it relates to the concept of breakeven, has been added as an appendix. This discussion also introduces the concepts of joint ventures and the value of downstream referrals.

Though the organization of Chapter Ten remains essentially the same, the basic model on which this chapter is based has been almost totally revised. The new model is a hospitalist practice that has only two services, a simplification from the previous edition. The discussion of supply chain operations and maximizing savings from evaluation of group purchasing organization discounts has been retained, but the supplies budget has been dropped. All perspectives have been replaced with updated versions. The problems have been revised to reflect the new content, though the general format is the same.

The discussion of cost centers in Chapter Eleven has been modified slightly to recognize both service- and product-producing activities, and all perspectives and problem sets have been updated.

The previous Chapter Twelve perspectives have been dropped, and two new ones have been added.

Chapter Thirteen has been updated to provide a discussion of evolving issues in provider payment. Among these issues are value-based purchasing, changes in payment for hospital readmissions and never events, and bundled payments. There is a more robust discussion on the mechanisms that Medicare uses to pay for hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and physician services. All perspectives have been replaced with updated versions. There are new key terms.

The glossary has been completely updated, and includes each term defined in a chapter sidebar and each key term.

The website for this book, including the instructor's manual and Excel spreadsheets, is located at www.josseybass.com/go/zelman4e. Comments about this book are invited and may be sent to publichealth@wiley.com.

Acknowledgments

We attempt throughout this book to challenge and enlighten. Quantitative as well as qualitative issues are presented in an effort to help the reader better understand the wide range of issues considered under the topic health care financial management. We would like to thank the many students who over the past several years have pointed out errors, offered suggestions and improvements, and provided new ways to solve problems.

Our particular thanks go to Wafa Tarazi, Yurita Yakimin, Abdul Talib, Yen-Ju Lin, PhD, Tae Hyun Kim, PhD, and Julie Peterman, CFA, for their review of various chapters and problem sets. We also offer special thanks to Charles Walker, MBA, CPA, for his dedication and tireless efforts in reviewing the key chapters and problem sets of this book.

Proposal reviewers Steven D. Culler, Magdalene Figuccio, John Fuller, Kirk Harlow, Kelli Haynes, Robert Jeppesen, Charles Kachmarik, Eve Layman, David Lee, Cynthia Lerouge, Anne Macy, Michael Nowicki, William J. Oliver, Mustafa Z. Ounis, Theresa Parker, Kyle Peacock, Jen Porter, Patricia Poteat, Howard Rivenson, Judi Schack-Dugre, Robert Shapiro, Karen Shastri, Dean Smith, Sandie Soldwisch, Wendy Tietz, Bill Wakefield, and Steve Zuiderveen provided valuable feedback on the third edition and our fourth edition revision plan.

Most of all, we would like to thank our families for their encouragement and support and for their understanding during the countless hours we were not available to them.

The authors apologize for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful for notifications to Michael McCue, at mccue@vcu.edu, of any corrections that should be incorporated in the next edition or reprint of this book and posted on the book's webpage.

The authors and the publisher gratefully acknowledge the copyright holders for permission to reproduce material in the perspectives throughout the book.

The Authors

William N. Zelman is a full professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He specializes in health care financial management, focusing on management-related issues, including organizational performance and cost management. He has served as director of the residential master's degree programs at UNC and is past chair of the Association of University Programs in Health Administration Task Force on Financial Management Education. He has authored or coauthored five books and numerous articles and has been an editorial board member or reviewer, or both, for a number of journals. He has extensive international experience, serving as a consultant to and presenting courses for academic, governmental, and other international organizations, primarily in South Asia and Central Europe.

Michael J. McCue is the R. Timothy Stack Professor of Health Care Administration in the Department of Health Administration at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. His research interests relate to corporate finance in the health care industry and the performance of hospitals, multihospital systems, and health plans. His previous research examines the determinants of hospital capital structure, the factors influencing hospitals' cash flow and cash on hand, and the evaluation of hospital bond ratings. His current research examines the effects of health reform on the financial performance of commercial health plans.

Noah D. Glick is currently a senior health care consultant for FTI Consulting in its corporate finance division, where he is engaged in physician strategy and health care analytics. Previously, he was administrative director for Rehabilitation Medical Associates and the South Shore Hospitalist Group outside Boston. Prior to that, he was a senior consultant for Integrated Healthcare Information Services in Waltham, Massachusetts, and a staff member in the Department of Decision Support at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He also taught simulation modeling in the master's in health administration program at UNC.

Marci S. Thomas is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she teaches health care consulting, strategy, and financial leadership. She is also a principal and director of quality control at Metcalf-Davis, CPAs. She consults with health care organizations, educational institutions, and other not-for-profit organizations and their boards on internal control, vulnerability to risk and fraud, strategic planning, and governance issues. She is a nationally recognized speaker on managing accounting issues in health care and related not-for-profit entities and on auditing these organizations. Thomas is a coeditor of and contributor to Essentials of Physician Practice Management (Jossey-Bass). Her book Best of Boards: Sound Governance and Leadership for Nonprofit Organizations, was published by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) in June 2011. She is a certified public accountant and a chartered global management accountant (CGMA).

CHAPTER 1

The Context of Health Care Financial Management

Never before have health care professionals faced such complex issues and practical difficulties in trying to keep their organizations competitive and financially viable. With disruptive changes taking place in health care legislation and in payment, delivery, and social systems, health care professionals are faced with trying to meet their organizations' health-related missions in an environment of uncertainty and extreme cost pressures. These circumstances are stimulating high-performing provider organizations to focus on innovation to help lower costs and find creative ways to deliver services to a population whose members, while aging, are more informed and more demanding of a voice in their care and value for dollars spent than ever before.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the largest effort toward reform of the health care system since the advent of government entitlement programs in the 1960s. The goal of the ACA is to provide mechanisms to expand access to care, improve quality, and control costs.

But even before the enactment of the ACA in 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had articulated a vision for health care quality: “the right care for every person every time.” CMS's stated objective is to promote safe, effective, timely, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable care.

CMS also needs to control the rising cost of care, which has become unsustainable. To accomplish its objectives CMS has been working to replace its old financing system, which basically rewarded the quantity of care, with value-based purchasing (VBP), a system that improves the linkage between payment and the quality of care. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 authorized CMS to develop a plan for VBP for Medicare hospital services beginning in fiscal year 2009. The ACA provided the implementation plan.

Many of these changes have been the source of controversy and lawsuits. Until President Obama's reelection in 2012, state governments as well as many providers faced uncertainty about whether the ACA provisions, even though found to be constitutional earlier in 2012, would be repealed. Some hesitated to move forward with implementation plans.

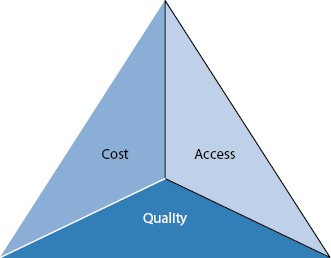

Regardless of whether or not all parties agree about the legislative outcome, the goal of the U.S. health care system remains to finance and deliver the highest possible quality to the most people at the lowest cost (Exhibit 1.1). But responses to today's challenges have resulted in a new business model that providers are embracing by controlling costs, developing new service offerings, and implementing new information technology, thereby creating added value (see Perspective 1.1 and Exhibit 1.2).

No matter what their political view is, people generally agree that the financial platform on which the health care system rests cannot be sustained. There is a clear need to reduce the proportion of the gross domestic product (GDP) spent on health care. Since the 1960s, hospitals have experienced increases in utilization, accompanied by increases in payments from government as well as from commercial payors. Medicare market basket updates have increased an average of 3.2 percent annually since that time. Under Medicare's new payment model, utilization and reimbursement are expected to decline over time, limiting market basket and utilization increases to only 1.5 percent to 2 percent a year. In addition, the value-based payment structure will reward those organizations with better quality while penalizing those with poorer scores. Since Medicaid and commercial payors tend to follow Medicare models, this effect will be magnified.

Several disruptive trends are changing the competitive landscape. Where commercial and not-for-profit providers had distinct differences, now they are both heavily focused on cost, quality, market share, and how quickly they can get innovative products to market. For example, Duke University Health System, a not-for-profit health system, and LifePoint Hospitals, Inc., a commercial health system, formed a joint venture, Duke LifePoint Healthcare, to provide community hospitals and regional medical centers with innovative means of enhancing services, recruiting and retaining physicians, and developing new service lines. Insurers such as Humana and private equity groups have acquired health systems. Certain integrated health care organizations, such as the Mayo Clinic and Geisinger Health System, are directed by physicians. New technologies like mobile apps provide mid-level providers and consumers with the latest evidence-based guidance to aid in diagnosis and management of health issues. And hospitals are consolidating, taking the view that big is good, bigger is better, and biggest is better still.

Source: Adapted from K. Kaufman and M. E. Grube, The transformation of America's hospitals: economics drives a new business model, in Kaufman, Hall, & Associates, Futurescan 2012: Healthcare Trends and Implications, 2012–2017 (Health Administration Press, 2011).

| Old Medicare Business Model | New Post Reform Business Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Value proposition | More market share, more patients, more services, more revenues | Best possible quality at the lowest price |

| Direction of price | Upward—Saks Fifth Avenue | Downward—Walmart |

| Cost environment | Cost management | Cost structure |

| Direction of utilization | Always up since 1966, growth industry | Flat/maybe down, mature industry |

| Relationship between hospital and doctors | Parallel play | Highly coordinated and integrated |

| Payment | Fee-for-service | Something else |

| System of care | Patient services | Patient/population management |

| Organizing for value creation | One patient at a time | Comprehensive health care for covered population |

| Importance of scale | Small and medium hospitals could survive | Big, bigger, biggest |

Source: Kaufman, Hall, & Associates, published in Futurescan 2012: Healthcare Trends and Implications, 2012–2017, Society for Healthcare Strategy and Market Development of the American Hospital Association and the American College of Healthcare Executives.

To establish a context for the topics covered in this text, this chapter highlights key issues affecting health care organizations. It is organized into three sections: (1) changing methods of health care financing and delivery, (2) addressing the high cost of care, and (3) establishing value-based payment mechanisms. Without question the health care industry is undergoing rapid change (Exhibit 1.3). The providers who are open-minded and informed, embrace change, and look for effective solutions will be the ones who thrive in this uncertain environment.

The push toward health care reform began back in the early 1990s during the Clinton administration. However, it did not make significant inroads until President Obama signed the ACA into law in early 2010, though the ACA is complex and has numerous provisions. The provisions that are expected to have the most significant impact on the delivery and financing of care are noted in the following list and discussed in the remainder of this chapter.1

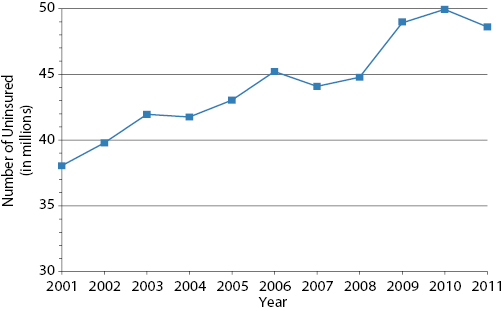

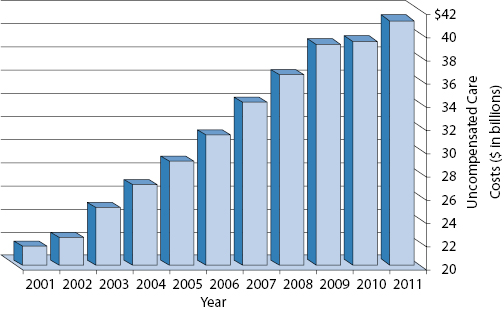

Between 2001 and 2010, the number of uninsured rose from 36 million to 50 million people, before decreasing slightly (Exhibit 1.4). This rise is due to several factors, including (1) health insurance and out-of-pocket costs becoming too costly for many individuals, even when they are working; (2) individuals being screened out by insurance underwriters because of preexisting conditions; (3) employers either scaling back employees' benefits or eliminating them altogether by hiring part-time workers; (4) state governments tightening Medicaid eligibility criteria; and (5) individuals voluntarily deciding not to purchase insurance for a variety of financial and nonfinancial reasons, including the assumption that they will not need care or that they will be taken care of by the “system” anyway. As a result, uncompensated care costs have doubled over the past decade (Exhibit 1.5), which has placed a tremendous burden on health care facilities, especially community hospitals.

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2012 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

Source: Data from Health Forum, American Hospital Association Annual Survey Data, 1980–2011 (January 2013).

The ACA authorizes a competitive insurance marketplace at the state level and provides for two types of exchanges, an individual exchange and a small business exchange. The individual exchange provides a mechanism for implementing the individual mandate for those who either do not have access to health insurance through an employer plan or who are uninsured for other reasons. The small business exchange provides access for small businesses, enabling them to improve the quality of health insurance for their employees by pooling their buying power and providing multiple health insurance options.

States have the ability to choose whether they want to operate their exchanges themselves. For those that do not want to develop and manage their exchanges, the federal government will do it for them. These exchanges begin operation in 2014.

The ACA provides for a minimum benefits package; however, participants will be able to shop for health insurance from among an array of commercial health insurance products with varying levels of deductibles, coinsurance, and additional benefits over and above the minimum. The benefit packages are referred to as bronze, silver, gold, and platinum, depending on how much participants choose to pay.

Tax credits are available to low-income consumers, phasing out at 400 percent of the federal poverty level. In addition, consumers will not need to worry about denial of coverage because of any preexisting conditions they may have. The exchanges should promote transparency, to assist the participants in making an informed decision.

The health insurance exchanges, along with other ACA provisions, are expected to make coverage available to 32 million previously uninsured people by 2019. If this works as intended, it should reduce the amount of charity care currently being provided by providers, especially hospitals. However, because the rules providing for a tax penalty for individual noncompliance with the insurance mandate have some exceptions, it is possible that the benefit to providers will not be as effective as originally forecast.

An ACO is a voluntary group of health care providers who come together to provide coordinated care to a patient population in order to improve quality and reduce costs by keeping patients healthy and by reducing unnecessary service duplication. This mechanism was initially created to serve Medicare beneficiaries but has now expanded into the non-Medicare population.

Participation is open to networks of primary care doctors, specialists, hospitals, and home health care services in which the network members agree to work together to better coordinate their patients' care. In June 2012, there were 221 ACOs in the United States. The majority were sponsored by hospital systems (118), followed by physician groups (70), insurers (29), and community-based organizations (4), and were located primarily in urban settings with relatively dense populations. By January 2013, there were more than 250 ACOs. As will be more fully discussed in Chapter Thirteen, ACOs are rewarded for reducing the cost of care while maintaining or improving quality under a variety of risk-based or risk-sharing mechanisms now being tested. Although certain medical groups, such as the Permanente Medical Group, Mayo Clinic, Intermountain Health Care, and Geisinger Health System, have shown positive correlations between practice organization and better performance, the ACO mechanism is too new to conclude that it will ultimately show the savings and quality improvements it was designed to achieve.2

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a partnership between primary care providers (PCPs), patients, and their families to deliver a coordinated and comprehensive range of services in the most appropriate settings. The PCP takes full responsibility for the overall care of the patient over an extended period of time, including preventive care, acute and chronic care, and end-of-life support. The PCMH is a patient-centered model using evidence-based medicine, care pathways, updated information technology, and voluntary reporting of performance results. In 2011, the National Commission on Quality Assurance created a program that recognizes providers as PCMHs on one of three levels, based on meeting certain administrative standards and achieving a degree of quality reporting. Practices with robust information technology, which includes electronic record keeping, electronic disease registries, internet communication with patients, and electronic prescribing, are the ones most likely to achieve level 3 status.

The PCMH is a good way for a primary care provider to distinguish itself as a quality practice. Until recently there has been little payment advantage associated with being a PCMH; however, programs run by various Blue Cross Blue Shield plans and other insurers are demonstrating that the concept pays off. For example, in late 2012, Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey identified savings due to reduced emergency department use (26%) and reduced hospital readmissions (26%). At the same time, CMS announced that 500 practices with over 2,000 total physicians will participate in the comprehensive primary care initiative. WellPoint is expanding its program after announcing that it earned $2.50 to $4.50 for every dollar invested in its PMCH program.3