Contents

About the Companion Website

chapter 1: Introduction

The Veterinary Technician’s Role in Pathology

Technician Duties and Required Skills

Diagnosis

Immunity

Factors Involved in Infectious Disease

Common Terminology Necessary for Understanding Pathology

References

chapter 2: Canine Infectious Disease

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) or Hard Pad Disease

Canine Parvovirus Type 2 (CPV-2)

Canine Adenovirus Type 1 (CAV-1) or Infectious Canine Hepatitis (ICH)

Canine Infectious Tracheobronchitis or Kennel Cough

Leptospirosis

Canine Influenza Virus (CIV) or Dog Flu

References

chapter 3: Feline Infectious Disease

Feline Panleukopenia (FPV), Feline Distemper, Feline Parvo, Feline Infectious Enteritis

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV)

Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) or Feline AIDS

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP or FIPV)

Feline Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Toxoplasmosis

References

chapter 4: Rabies

Rabies Virus

References

chapter 5: Gastrointestinal Tract Disease

Oral Cavity

Esophagus

Stomach

Intestines

Liver

Pancreas

References

chapter 6: Urinary Tract Disease

Bacterial Cystitis or Urinary Tract Infection

Pyelonephritis

Urolithiasis (Urinary Calculi or Urinary Stones)

Urinary Obstruction or Blocked Tom (Feline)

Feline Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD)

Acute Renal Failure (ARF)

Chronic Renal Failure (CRF), Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), or Chronic Renal Disease (CRD)

References

chapter 7: Reproductive Disease

Vaginitis

Pyometra

Dystocia

Mastitis

Mammary Neoplasia

Prostate Disease

Testicular Disease

Male Reproductive Neoplasia

References

chapter 8: Endocrine Disease

Hyperthyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Hyperadrenocorticism or Cushing’s Disease/Syndrome

Hypoadrenocorticism or Addison’s Disease

Diabetes Mellitus or Sugar Diabetes

Diabetes Insipidus (DI), or Weak or Watery Diabetes

References

chapter 9: Ocular Disease

Conjunctivitis or Pink Eye

Epiphora

Third Eyelid Prolapse or Cherry Eye

Entropion/Ectropion

Glaucoma

Corneal Ulcers

Chronic Superficial Keratitis or Pannus

Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca or Dry Eye

Anterior Uveitis, Iridocyclitis, or Soft Eye

Cataracts

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) or Progressive Retinal Degeneration (PRD)

References

chapter 10: Integumentary Disease

Parasitic Skin Infections

Fungal Skin Infections

Miscellaneous Skin Disorders

Neoplasias Originating from the Skin and Associated Structures

References

chapter 11: Musculoskeletal Disease

Bone Fractures

Osteosarcoma (OSA)

Panosteitis (Pano)

Osteoarthritis or Degenerative Joint Disease (DJD)

Hip Dysplasia

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)

Patellar Luxation

Cranial or Anterior Cruciate Ligament (CCL or ACL) Rupture or Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease (CCLD)

Intervertebral Disk Disease (IVDD)

Myasthenia Gravis

References

chapter 12: Hematologic and Lymph Disease

Erythrocyte Disorders

Leukocyte and Lymph Disorders

Thrombocyte and Coagulation Disorders

References

chapter 13: Diseases of Rabbits, Guinea Pigs, and Chinchillas

Urolithiasis/Bladder Sludge

Gastric Stasis

Ulcerative Pododermatitis, Bumblefoot, or Sore Hock

Malocclusion or Slobbers

Heat Stroke

Respiratory Infection

Mastitis

Rabbit Hairballs or Trichobezoar

Rabbit Buphthalmia

Rabbit Uterine Adenocarcinoma

Scurvy

Antibiotic-Associated Enterotoxemia

Streptococcal Lymphadenitis, Cervical Lymphadenitis, or Lumps

Cavian Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Cavian Leukemia/Lymphosarcoma

Guinea Pig Dystocia

Chinchilla Fur Slip and Fur Chewing

Chinchilla Gastric Tympany (Bloat)

References

chapter 14: Diseases of Ferrets

Pancreatic Beta Cell Tumor or Insulinoma

Adrenal Disease or Hyperadrenocorticism

Aplastic Anemia/Estrogen Toxicity

Lymphoma/Lymphosarcoma

Influenza

Epizootic Catarrhal Enteritis (ECE) or Green Slime Diarrhea

Ferret Systemic Coronavirus (FRSCV) or Ferret FIP

Canine Distemper

Gastric Foreign Bodies

References

chapter 15: Diseases of Hamsters, Gerbils, and Rats

Malocclusions

Proliferative Ileitis, Proliferative Enteritis, or Wet Tail

Antibiotic-Associated Enterotoxemia or Clostridial Enteropathy

Tyzzer’s Disease or Clostridium piliforme

Respiratory Infections

Neoplasia

Ulcerative Pododermatitis or Bumblefoot

Chromodacryorrhea or Red Tears

Arteriolar Nephrosclerosis or Hamster Nephrosis or Renal Failure

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV)

Gerbil Epileptiform Seizures

Gerbil Tail Slip or Tail Degloving

References

Index

This edition first published 2014

© 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Editorial Offices

1606 Golden Aspen Drive, Suites 103 and 104, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by Blackwell Publishing, provided that the base fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For those organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payments has been arranged. The fee codes for users of the Transactional Reporting Service are ISBN-13: 978-1-1184-3421-5/2014.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting a specific method, diagnosis, or treatment by health science practitioners for any particular patient. The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. Readers should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organization or Website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. No warranty may be created or extended by any promotional statements for this work. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any damages arising herefrom.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, Amy, 1973– author.

Small animal pathology for veterinary technicians / Amy Johnson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-43421-5 (pbk.)

I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Animal Diseases–Handbooks. 2. Pets–Handbooks. 3. Animal Technicians–Handbooks. SF 981]

SF769

636.089′607–dc23

2013039731

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Cover image: top cat image courtesy Deanna Roberts; right top dog image courtesy Michael Curran; right bottom dog image courtesy Emma Worsham

Cover design by Nicole Teut

To my family and friends who put up with my absence throughout this process and support me in all my endeavors, no matter how crazy they may sound. Thank you Keith and Cooper.

To my present animals that sat keeping me company and kept my feet warm as I worked on this project.

To my past animals who inspired my need for greater knowledge and became a part of this project as case studies or images.

To everyone who came to my aid as I begged for images and came through with a great selection.

To my students who inspire me and believe in what I am doing for them.

And to my friend Michelle who spent countless hours helping me edit as she “did not want to have me look bad.” I could not have done it as well without your help.

About the Companion Website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/johnsonvettechpath

The website includes:

- Images from the book in PowerPoint for downloading

- Review questions and answers

- Case studies illustrating the process of handling the patient

c h a p t e r 1

Introduction

The Veterinary Technician’s Role in Pathology

For a veterinary technician, there are certain tasks not allowable by law. These tasks include making a diagnosis, determining a prognosis, prescribing medication, initiating treatment, or performing surgery. Just because a technician cannot make a diagnosis does not mean he or she is not an integral part of the diagnostic team. Understanding pathology is an important part of the veterinary technician’s job, meaning it cannot be overlooked.

TECH BOX 1.1: Veterinary technicians play a role as an integral part of the diagnostic team.

Why does the veterinary technician need pathology information? This question has many answers:

- The role of client education is often a task that is the job of the technician. Veterinary technicians will advise clients on the phone and in person on how to best care for their pets.

- It is important to understand disease to prevent the spread of pathogens from patient to patient. It is the role of technicians to make sure they are doing what they can to keep their patients in good health.

- As a technician, there is a need to understand how to appropriately care for the patient. This understanding of the disease process will facilitate patient care.

- An understanding of pathology will aid in protecting clients, co-workers, and the technician themselves from zoonotic diseases.

- A technician who knows the disease process is able to anticipate the veterinarian’s needs, expediting patient care.

Technician Duties and Required Skills

Technician duties will include patient care, client education, laboratory diagnostics, assisting the veterinarian, and treatment. It is important to note that every veterinarian/clinic/hospital will have different thoughts as to what a technician’s duties will be, thus making it important that the technician understands what his or her role is.

Some of the necessary skills involved in dealing with these ill patients include

- Client education and communication skills

- The ability to speak with owners over the phone and in person.

- The ability to speak clearly with owners during the intake process and answer questions in terms that are correct but on a level that the client will understand.

- The ability to update clients on how their animals are doing and progressing.

- The ability to convey information between the veterinarian and owner.

- The ability to explain invoices/estimates to clients so there is an understanding of why the procedure and cost are necessary for the treatment of their pet.

- The ability to discharge a patient and give owners any information needed to continue the care of their animal.

- The ability to train owners how to medicate or perform treatments that may be necessary once the animal is home.

- Laboratory and other diagnostic skills

- The ability to properly collect specimens including urine, feces, blood, and tissues.

- The ability to properly submit and package samples to reference laboratories.

- The ability to perform a complete blood count (CBC) and other basic hematological procedures.

- The ability to run blood chemistry machines and enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).

- The ability to collect cytologic specimens, set up slides, and examine slides.

- The ability to collect samples for bacterial evaluation and set up and read culture and sensitivity tests.

- The ability to set up, perform, and develop radiographs, ensuring the safety of all persons and animals involved.

- The ability to prepare and restrain patients for other diagnostic imaging techniques including ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) scans.

- The ability to prepare the patient, set up and clean equipment, and restrain the patient for endoscopic procedures.

- The ability to prepare the patient and equipment for other specialized diagnostic procedures.

- Treatment skills

- The ability to place intravenous catheters (ICVs) in veins including cephalic, lateral saphenous, and jugular veins.

- The ability to prepare fluid bags and medications.

- The ability to calculate the patient’s fluid rates.

- The ability to administer medications through routes including injection, oral, and topical.

- The ability to isolate infectious materials and prevent further spread of contagious diseases.

- The ability to keep the patient comfortable and in clean quarters.

- The ability to advocate for the patient and keep his or her best interests first and foremost.

- Other skills

- The ability to perform dosage calculations and other important veterinary calculations.

- The ability to induce the patient for surgery, maintain and monitor anesthesia, prepare the patient for surgery, and assist the veterinarian in surgery.

- The ability to sterilize instruments, prepare surgical packs, and maintain sterility.

- The ability to restrain patients for examinations and procedures, ensuring the safety of the animal and all persons involved.

- The ability to lift patients on to exam tables, into and out of cages, and help patients ambulate if they are unable to.

- The ability to perform euthanasia or aid in the process.

- The ability to maintain patient records and hospital logs.

- The ability to log and track controlled substances.

- The ability to triage patients and deal with multiple animals.

There are other additional skills and duties that will be discussed with specific pathologies and highlighted by “Technician Duty” boxes.

Diagnosis

The word “diagnosis” literally means “a state of complete knowledge” and is used to label the condition the patient is suffering from. Types of diagnosis include

- A presumptive diagnosis is the identification of the likely cause of disease.

- A definitive diagnosis is the identification of the definite cause of disease; this type of diagnosis involves diagnostic testing.

- A differential diagnosis is a list of possible diseases the patient could have. Testing will aid in ruling diseases out and narrowing the list.

What is involved in a diagnosis and what is the technician’s role? Not many patients will present with signs so distinct that the veterinarian knows immediately what disease they have. Achieving a diagnosis takes work and there is a process involved. First a history will need to be taken and a physical examination performed. A problems list will be generated that will allow the veterinarian to form a differential diagnosis. Performing diagnostic testing or imaging will allow for conditions to be crossed off that list. Technicians play a crucial role in this process, and it does not stop there. Once the veterinarian initiates treatment, the technician will provide that treatment. Client communication is necessary throughout the animal’s hospitalization, and more client education will be necessary upon the patient’s release. What this means is the veterinary technician is a critical part of the whole process.

Immunity

Immunity is the ability of the body to fight off disease and can be categorized in several different ways.

Non-specific immunity/resistance is general protection that does not initiate a response against a specific pathogen. The first line of defense is provided by mucous membranes and skin providing a physical barrier. Innate immunity, including inflammation, fever, antimicrobial proteins, and phagocytes, is the body’s second line of defense. Specific immunity/resistance is the body’s third line of defense, giving the body the ability to target and destroy specific antigens. Specific immunity involves lymphocytes that produce antibodies and memory cells.

Active immunity is formed when the body is allowed to form its own antibodies against a pathogen. Examples of active immunity include antibodies formed when the body is exposed to a disease or a vaccine. Passive immunity is produced when the body receives preformed antibodies, such as in the instance of colostrum or plasma.

Cellular immunity (cell-mediated immunity) is immunity involving the activation of T cell lymphocytes. These T cells have different functions:

- Cytotoxic T cells have the ability to attach to the antigen and attack it.

- Helper T cells enhance the activities of other immune responses.

- Supressor T cells aid in control of the immune response.

- Memory T cells create a memory of the antigen for a quicker response with the second exposure.

Humoral immunity involves production of antibodies from B cell lymphocytes. B cells transform into plasma cells creating antibodies, which work by neutralizing the pathogen, preventing cell attachment, immobilizing bacteria, and enhancing phagocytosis. Antibodies formed are for specific antigens and initiate memory B cells that create a quicker response in future exposures.

Factors Involved in Infectious Disease

How can two animals come in contact with a disease in their environment and only one of them get sick? The answer involves factors or variables involved with each patient and circumstance. First are host factors, dealing with the patients themselves. Age, nutritional status, health status, medications, immunization status, and stress will all play a role in how well a patient’s immune system will protect it. Next are environmental factors, which involve temperature, humidity, and sanitation. Lastly, agent factors involve the micro-organism. Virulence, mode of transmission, and the amount of exposure needed aid in determining how a patient’s immune system will react to each pathogen.

Common Terminology Necessary for Understanding Pathology

- Bacterial translocation: The movement of bacteria or bacterial products across the intestinal lining to either the lymphatics or peripheral blood circulation.

- Bacterin: An immunization against a bacterial agent.

- Biological vector: An organism in whose body a micro-organism develops or multiplies prior to entering the definitive host.

- Carrier: A living organism that serves as host to an infection yet shows no clinical signs of the disease.

- Clinical sign: Objective changes an observer can see or measure in a patient.

- Contagious infectious disease: An infectious disease that can be passed from one animal to another.

- Disease: Any changes from the state of health disrupting homeostasis.

- Endemic: A disease that is present in the community at all times.

- Fomite: An inanimate object that transmits a contagious infectious disease.

- Homeostasis: The ability of an organism to maintain its internal environment within certain constant ranges.

- Horizontal disease transmission: Transmission of disease among unrelated animals; can occur through direct contact or vectors. Horizontal disease transmission occurs when an animal comes in contact with a disease in his or her environment.

- Incubation period: The period of time from when a pathogen enters the body until signs of disease occur.

- Infection: Invasion and multiplication of a micro-organism in body tissues.

- Infectious disease: A disease caused by a micro-organism.

- Latent infection: An infection where the individual does not show signs of disease, unless under stressful conditions.

- Local disease: A disease that affects a small area or part of the body.

- Mechanical vector: An organism that transmits a micro-organism by moving it from one location to another.

- Morbidity: A ratio of sick to well in a population; refers to how contagious a disease is.

- Mortality: The number of deaths among exposed or infected individuals.

- Palliative: Relieving clinical signs/symptoms without curing disease.

- Pathogen: An infectious agent or micro-organism.

- Pathognomonic sign: A hallmark sign or one that is unique to a particular disease.

- Pathology: The study of disease.

- Prognosis: The estimate of the likely outcome of disease.

- Reservoir: A carrier or alternative host that maintains an organism in the environment.

- Resistance: The ability to ward off disease (immune).

- Subclinical or unapparent infection: An infection where clinical signs cannot be observed.

- Susceptibility: The lack of immunity or vulnerability to disease.

- Symptom: Subjective changes not obvious to the observer, requiring the patient to report them.

- Systemic disease: A disease that affects a number of organs/tissues or body systems.

- Vaccine: An immunization against a viral agent.

- Vector: Anything that transmits a contagious infectious disease.

- Vertical disease transmission: Transmission of disease from parent to offspring in the period prior to birth or immediately after birth. Examples of vertical disease transmission include transplacental transmission of disease or transmission through colostrum or lactation.

- Zoonotic disease: An infectious disease that can be passed from animal to man.

References

“Biology-Online Dictionary.” Accessed February 27, 2013. http://www.biology-online.org/dictionary/Main_Page.

Leifer, Michelle. “What Do Veterinary Technicians Do?” Vetstreet. Accessed February 27, 2013. http://www.vetstreet.com/learn/what-do-veterinary-technicians-do.

Levinson, Warren. “Immunology.” In Medical Microbiology & Immunology: Examination & Board Review. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2004.

“Medical Dictionary.” Accessed February 27, 2013. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/.

c h a p t e r 2

Canine Infectious Disease

There are numerous infectious agents ubiquitous in the environment with which dogs come into contact. Most of these agents can be fought off by the immune system, but multiple variables will allow that protection to fail (discussed in chapter 1). Vaccines will protect many dogs, and yet patients will still present to veterinary clinics with these infections.

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) or Hard Pad Disease

Description

Distemper virus is a highly contagious systemic infection caused by an enveloped ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus from the family Paramyxoviridae. As a member of the Morbillivirus genus, it is very closely related to human measles virus. Distemper is seen in domestic dogs and ferrets but transmission can be linked to wildlife such as skunks, minks, raccoons, coyotes, wolves, and foxes. It is a fairly labile in the environment, being easily killed by common disinfection methods. Incubation for distemper virus is approximately 2 weeks.

Transmission

- The main transmission route for distemper is through aerosolization. Respiratory secretions contain virus, although all other secretions should be considered contagious. Distemper can be passed from mother to fetus across the placenta.

Clinical Signs

- Highest rate of infection is among young unvaccinated puppies.

- Dogs with distemper may have a fever accompanying the disease.

- Respiratory signs include severe ocular and nasal discharge and pneumonia (Figure 2.1).

- Integumentary signs include pustules on the abdomen and hyperkeratosis of the pads and nose. These tissues produce excess keratin, causing a waxy hard surface commonly called “hard pad.”

- Vomiting and diarrhea are clinical signs associated with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Dental disorders arise from enamel hypoplasia, as the enamel does not properly form on developing teeth in puppies with the infection (Figure 2.2).

- Seizures are common with distemper. If the dog is exposed to distemper after birth, the seizures may develop during the course of the disease or be delayed 1–3 weeks after recovery from the other clinical signs. These seizures will range from mild to severe. “Chewing gum” seizures and focal seizures in the facial muscles are common.

- Puppies exposed to distemper prior to birth will develop seizures within the first few weeks of life, while other clinical signs are absent.

TECH BOX 2.1: Distemper is one of the most common causes of seizures in puppies less than 6 months old.

Diagnosis

- Distemper is most commonly diagnosed based upon presenting clinical signs, physical exam, and history.

- Radiographs can be used to diagnose pneumonia (Figure 2.3).

- Reference lab testing includes polymerase chain reaction (PCR), antibody titers, and immunofluorescent antibody assay (IFA).

- In-house testing includes distemper antigen test kits and routine laboratory work (Table 2.1), although the lab values are not definitive. Distemper inclusions can be found in the red blood cells (RBCs) and white blood cells (WBCs) of infected patients (Figure 2.4) on a routine blood film.

Treatment

- Treatment is supportive care targeted at the patient’s clinical signs.

- Treatment includes intravenous (IV) fluids, correction of electrolyte imbalances, antibiotic drug therapy to prevent secondary bacterial infections, anticonvulsants, and oxygen therapy.

- Even with treatment, the disease will most often be fatal.

Table 2.1 Distemper laboratory work

| Morphology changes on blood film |

Inclusions found in RBC and WBC:

Dark purple

Round to oval

Inconsistent size |

| Blood cell count changes |

Leukopenia first 3–6 days of infection |

| PCV/TP |

Increase due to hemoconcentration |

| Blood chemistry |

Hypoglycemia due to anorexia and vomiting |

| Electrolytes |

Imbalances due to dehydration and anorexia |

| Urine changes |

Increase in USG due to dehydration |

Client Education and Technician Tips

- Distemper is one of the leading causes of death in unvaccinated dogs.

- Vaccination, isolation, and sanitation are key in preventing the spread.

- High-risk young puppies can be given human measles vaccine. This offers cross-protection as the antibodies formed will recognize distemper virus but will not interfere with maternal distemper antibodies.

- If a dog survives distemper, he or she may have lifelong problems, including dental and central nervous system (CNS) problems (seizures).

- “Old dog encephalopathy“ (ODE) is a condition seen in surviving dogs as they age. The virus remains long term in their brain tissue and can cause encephalitis. It is important to note that these dogs are not contagious and will not develop any other signs of distemper. Dogs with ODE will exhibit CNS signs such as seizures, ataxia, and head pressing.

TECH BOX 2.2: With distemper, the long-term prognosis is questionable. Patients may not recover from neurological clinical signs.

Canine Parvovirus Type 2 (CPV-2)

Description

Canine parvovirus type 2, a highly contagious virus, will cause an acute severe gastroenteritis in dogs. CPV-2 is seen in wild canids as well as domestic dogs. This non-enveloped deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus is from the Parvoviridae family, and although there are many species that are affected by viruses in this family, CPV-2 will not cross species lines. Dogs with parvovirus start to exhibit clinical signs within 4–9 days after exposure. Viruses in the Parvoviridae family are some of the most resistant viruses known. CPV-2 will live in the environment for approximately a year, possibly longer. The virus is resistant to some disinfectants, extreme temperatures, and changes in pH; however, dilute bleach will kill the virus on hard surfaces.

Transmission

- Parvovirus is spread through the feces. Dogs are infected via the fecal-oral route. The virus is spread through direct contact with the infected dog, feces, or though vectors, especially fomites.

- The virus is shed in the feces of infected dogs for up to 3 days prior to onset of clinical signs and up to 3 weeks post-recovery.

- Parvovirus initially replicates in the lymphoid tissue of the oral cavity and pharynx, then spreads to the bloodstream. The virus attacks rapidly dividing tissue or cells, including the bone marrow, lymphopoietic tissue, and intestinal crypt cells.

Clinical Signs

- Common signalment is puppies less than 1 year of age, although the virus cannot be ruled out in older dogs with clinical signs consistent with CPV-2.

- Acute onset of vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and lethargy are common presenting clinical signs. Diarrhea is most often hemorrhagic and has a distinct odor to it.

- Fever often accompanies the other clinical signs.

- Some dogs can be asymptomatic carriers of parvovirus.

Diagnosis

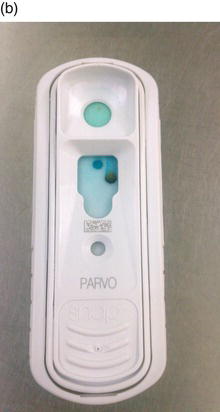

- The most common diagnosis is through the use of an in-house ELISA test. This test detects the parvovirus antigen in the feces of infected dogs and is considered definitive (Figure 2.5).

- Reference tests are available but are rarely used due to access to in-house testing.

- Laboratory blood testing may help add to the developing diagnosis but is not definitive if used alone (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Parvo laboratory work

| Blood cell count changes |

Leukopenia, especially lymphopenia and neutropenia |

| PCV/TP |

Increase due to hemoconcentration |

| Blood chemistry |

Hypoglycemia due to vomiting and anorexia |

| Electrolytes |

Imbalances due to dehydration and anorexia |

| Urine changes |

Increase in USG due to dehydration |

TECH BOX 2.3: A definitive diagnosis of parvovirus is easily obtained in house. The testing is easily available, fairly inexpensive, and will give the owners and veterinarian a quick diagnosis.

Treatment

- Treatment is supportive and aimed at correcting electrolyte and fluid imbalances, stopping bacterial translocation and septicemia, and controlling clinical signs.

- Often dogs with CPV-2 will be taken off of any oral food, water, or medications until the vomiting has subsided. Many veterinarians advocate parenteral feeding early in treatment. Getting the enterocytes nutrients will speed the patient’s recovery. In order to make the early enteral nutrition (EEN) successful, the patient’s vomiting must be controlled.

- Parvo puppies present severely dehydrated as a result of vomiting and diarrhea, making rehydration and electrolyte balance a priority. Ideally the patients will receive IV crystalloid fluid therapy, as subcutaneous (SQ) fluids pose a higher risk for infection due to contamination and often cannot keep up with the dog’s hydration needs. Once an IV catheter is placed it is important to replace it every 48–72 hours to avoid infection and inflammation.

- Most clinics will have their own “parvo cocktail” used for treatment of the patient. These vary but will often contain a mixture of crystalloid fluid with dextrose, broad-spectrum antibiotics, electrolytes, antiemetics, and analgesics. Some may also include immune-boosting vitamins.

- Dogs with parvo should be hospitalized in an isolation ward. Due to a weakened immune system these dogs are susceptible to secondary infections. Keeping them in the isolation ward protects them from the infections of other hospitalized patients. This isolation also serves to protect the other patients from infection with the highly contagious parvovirus.

Technician Duty Box 2.1

It is important to keep parvo patients and their cages clean and free of urine, feces, and vomit. This can be a difficult task based on the amount of diarrhea excreted, so the veterinary technician must stay on top of monitoring these patients.

Client Education and Technician Tips

- Vaccination, isolation, and sanitation are key in preventing the spread of this virus.

- Some breeds have been found to be more susceptible than others. These breeds include Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers, Pit Bulls, German Shepherds, and Labrador Retrievers. These breeds may require an extra vaccine for full protection from the virus.

- Most dogs presenting to clinics for parvo are puppies, but we must not overlook the fact that CPV-2 can also be seen in adult dogs. Unvaccinated or inappropriately vaccinated old dogs or dogs with weakened immune systems and dogs with vaccine failures may be at risk for CPV-2.

- Most dogs that develop and survive parvo will be immune to the disease. Owners do not need to worry about the dogs re-infecting themselves when they go home.

- With intensive in-hospital treatment the prognosis for dogs with CPV-2 is good.

TECH BOX 2.4: Although parvoviruses are very difficult to kill in the environment, dilute bleach will kill the virus on hard surfaces.

Canine Adenovirus Type 1 (CAV-1) or Infectious Canine Hepatitis (ICH)

Description

Infectious canine hepatitis is a multisystemic infection of domesticated dogs as well as wild canids and bears. The infection is caused by a non-enveloped DNA virus from the Adenoviridae family. As a result of the virus lacking an envelope it will survive in the environment for months, especially in cool climates. The virus is susceptible to dilute bleach and many other disinfectants. Infectious canine hepatitis is adenovirus type 1; although it is closely related to canine adenovirus type 2 (a common cause of canine infectious tracheobronchitis), they are two distinct viruses. The incubation period of CAV-1 is 4–9 days.

Transmission

- CAV-1 enters the body through contact with infected urine, feces, or saliva in the environment. Dogs with CAV-1 will shed virus in their urine for up to 6 months.

- Vectors are an important route of transmission, especially urine-contaminated fomites.

- Once in the body, the virus replicates in the tonsils and spreads to associated lymph nodes. The virus will spread via the bloodstream to tissues of the liver, kidney, spleen, lung, and eye.

Clinical Signs

- CAV-1 is most often seen in dogs less than 1 year of age.

- Clinical signs will vary and will range from subclinical infection to acute death.

- Because initial replication occurs in the tonsils, dogs with CAV-1 may have tonsillitis, although this most often goes unnoted by the owners or veterinarians.

- CAV-1 is often accompanied by a fever.

- Hepatitis and liver necrosis will cause hepatoencephalopathy. Hepatoencephalopathy is a condition in which hepatic dysfunction leads to increased ammonia levels in the blood. Ammonia has a toxic effect on the brain, causing clinical signs including seizures, stupor, blindness, ataxia, and head pressing.

- Hepatitis may also cause coagulation dysfunction, as the liver is responsible for production of many of the clotting factors. Patients will present with peticiation, bruising, bloody diarrhea, hematemesis, and other bleeding disorders. This hemorrhage can be severe and may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC).

- Depending on the extent of the liver damage, patients may present with icterus tissues, serum, and urine (Figure 2.6).

- Viral colonization in the kidney can lead to pyelonephritis, resulting in chronic renal disease.

- CAV-1 will often cause ocular disorders, including anterior uveitis and corneal edema. Corneal edema is referred to as “blue eye” because of the bluish opacity seen in the eye. This will spontaneously resolve in most surviving dogs.

Diagnosis

- CAV-1 is most commonly diagnosed based on presenting clinical signs, physical exam, history, and laboratory work-up (Table 2.3).

- Reference lab tests include virus isolation, serum antibody titers, and IFA.

- Histopathology at the time of necropsy reveals intranuclear inclusions in hepatocytes.

Table 2.3 CAV-1 laboratory work

| Blood cell count changes |

Leukopenia, especially lymphopenia and neutropenia

Thrombocytopenia

Anemia if hemorrhaging |

| PCV/TP |

Decrease if hemorrhage

Decrease in TP due to liver damage |

| Blood chemistries |

Increase in liver enzymes:

ALT, AST, alk. phos., GGT

Hyperbilirubinemia

Increased ammonia

Decreased BUN

Hypoalbuminemia

Decreased clotting factors

Hypoglycemia due to anorexia and decreased glycogen production |

| Bleeding times |

Increase due to lack of clotting factors |

| Urine changes |

Hyperbilirubinuria

Hematuria if bleeding in urinary tract or pyelonephritis |

Treatment

- As with other viruses, supportive care is imperative to the dog’s survival.

- Supportive care includes IV fluids with dextrose and electrolytes. SQ fluids are not advisable, especially in dogs with coagulation disorders.

- Due to leukopenia and a compromised immune system, CAV-1 infected dogs are often given broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat and prevent secondary infections.

- Blood transfusions are often performed to improve immune function by providing WBCs and aiding in correction of coagulation dysfunction. The blood transfusion provides clotting factors and platelets if the patient is deficient.

Client Education and Technician Tips

- Vaccination, isolation, and sanitation are key in preventing the spread. Infectious canine hepatitis is not as common now as it once was as a result of vaccination protocols.

- Vaccines for CAV-2 (infectious tracheobronchitis) should be used, as CAV-1 vaccines carry the risk for adverse side effects. Vaccines using CAV-1 were found to cause “blue eye” and renal dysfunction. The two viruses are so closely related that vaccination for CAV-2 will protect the dog from both adenoviruses.

TECH BOX 2.5: Vaccines labeled as DHLPP include CAV-2 and not CAV-1 as the name would suggest.

Canine Infectious Tracheobronchitis or Kennel Cough

Description

Any contagious respiratory disease of dogs that causes coughing can be considered kennel cough. This is a very broad diagnosis that includes many viruses, bacteria, or fungi. Common viral causes of kennel cough include canine adenovirus type 2 (CAV-2), parainfluenza virus, and canine herpes virus. Bordetella bronchiseptica is the bacteria commonly implicated in the infection. It is common to see dogs with dual infections. Most agents responsible for causing kennel cough are fairly labile and will not survive in the environment for long. Incubation periods will vary by organism, yet most are approximately a week.

Transmission

- Transmission occurs through aerosolization of organisms in respiratory secretions.

- Patients are infected when in close proximity with other dogs. This includes not only boarding facilities but shelters, animal hospitals/clinics, or daycare facilities as well.

TECH BOX 2.6: Kennel cough is not just a disease contracted in boarding kennels. Any dog in situations with multiple dog contact is at risk.

Clinical Signs

- Kennel cough can be seen in any age or breed of dog with a history of confinement with other dogs.

- Dogs with kennel cough will have a harsh, dry cough often elicited by gentle tracheal palpation.

- The coughing may be followed by retching and gagging, which may lead the owners to believe the dog is vomiting.

- Most dogs with kennel cough are healthy with the exception of the cough. Generally no fever, anorexia, or other clinical signs of disease are present.

- Some dogs will develop a more severe disease. Stress and age may be factors in determining how severe an infection may be. Dogs in this category will develop a fever, anorexia, depression, purulent nasal discharge, and a change in the cough from a developing pneumonia.

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis is most commonly based on clinical signs, physical exam, and history.

- Definitive diagnosis can be obtained through reference lab testing but is often unnecessary, as testing generally does not alter the treatment or prognosis.

Treatment

- Kennel cough is most often self-limiting; the dog’s immune system will clear the infection without medical intervention.

- Hospitalization is usually avoided as a result of the contagious nature of the disease.

- Cough suppressants can be prescribed but are often more for the owner’s comfort.

- Antibiotics may be used, especially if clinical signs worsen and pneumonia is suspected.

TECH BOX 2.7: Kennel cough is a self-limiting disease, meaning treatment is not always necessary.

Client Education and Technician Tips

- Immunization, sanitation, and isolation are key to stop the spread of this infection. Yet even immunized dogs can get the disease. There are multiple organisms that will cause kennel cough; unfortunately not all of them can be protected against with immunizations.

- Most boarding facilities, daycares, grooming facilities, and veterinary hospitals will require dogs be immunized with a DA2LPP and Bordetella bronchiseptica prior to being left in their care.

- If coughing is associated with walks, owners should be directed to use a harness that does not put pressure on the trachea the way a collar will. It is also best to recommend the dog not be walked while contagious.

Leptospirosis

Description

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease of humans and other animals that has been found to be the most widespread zoonotic disease in the world. Although it is found in North America, it is seen more prominently in countries with poor water purification systems and poor water quality. This disease is caused by spirochete bacteria in the genus Leptospira (Figure 2.7). There are over 200 recognized serovars of the species interrogans. The most clinically significant in North America are icterohemorrhagiae, canicola, pomona, grippotyphosa, bratislava, and autumnalis. The Leptospira bacteria can survive for months in moist soil and water, although survival times are longest in temperate climates. The incubation period is between 2 and 20 days.

TECH BOX 2.8: Leptospirosis is the most widespread zoonotic disease in the world.

Transmission

- Leptospirosis can infect any mammal, although some are more resistant than others. Any breed and age of dog age can become infected.

- Most common transmission route is through infected urine. The bacterium is shed in the urine of infected animals for up to 1 year post-recovery. Urine enters the body through mucous membranes or abraded skin or through ingestion of contaminated food or water sources.

- Fomites play a large role in the spread of leptospirosis, as objects become contaminated with infected urine.

- Leptospira can also cross the placenta and can spread through venereal transmission.

Clinical Signs

- Clinical signs of leptospirosis are often non-specific. Some dogs may be asymptomatic while others will die acutely.

- Acute phase dogs may present with fever, lethargy, anorexia, vomiting and diarrhea (V/D), polyuria and polydipsia (PU/PD), abdominal pain, muscle pain and weakness, and icterus. In this phase the bacteria are spreading through the blood and lymphatic system to all body tissues. During this phase, the body mounts an immune response to the infection and immunity starts to form.

- The convalescent phase, usually lasting 2 weeks, is the time frame when the immune system starts to clear the bacteria from many tissues, although the bacteria will remain in the kidney and potentially the liver. Clinical signs may wax and wane during this phase.

- The carrier or chronic phase occurs, as the bacterium is not eliminated from the kidneys, liver, or eyes with proper antibiotic therapy. Patients will have clinical signs associated with chronic nephritis, active hepatitis, and uveitis.

- Death from leptospirosis is associated with acute kidney failure and/or liver necrosis.

Diagnosis

- Leptospirosis is a disease that cannot be diagnosed definitively in-house and requires reference lab testing. In-house laboratory diagnostics, however, can help support a developing diagnosis of leptospirosis (Table 2.4).

- Reference lab tests include antibody titers, microscopic agglutination test (MAT), and PCR. These tests require blood and urine samples that are collected prior to antibiotic administration. Timing of sample collection often determines if a blood or urine test is best suited for each patient; it is often best to send both samples. The bacteria first appears in the bloodstream but is then cleared from the bloodstream and only found in the urine.

TECH BOX 2.9: Although no in-house testing for leptospirosis is available, patients should be labeled as “leptospirosis suspects” if the disease is on the rule out list.

Table 2.4 Leptospirosis laboratory work (may vary based on clinical signs)

| Blood cell count changes |

Leukocytosis

Thrombocytopenia |

| PCV/TP |

Increase due to hemoconcentration |

| Blood chemistries |

Increase in liver enzymes:

ALT, AST, alk. phos., GGT

Hyperbilirubinemia

Azotemia

Increase in ammonia

Hypoalbuminemia

Decrease in clotting factors

Electrolyte imbalances due to kidney dysfunction |

| Bleeding times |

Increase |

| Urine changes |

Bilirubinuria

Proteinuria

Glucosuria

Increase in cellular casts

Decrease in USG |

Treatment

- Antibiotics are used in conjunction with supportive therapy with this bacterial infection.

- The initial infection is most commonly treated with doxycycline or penicillin followed by long-term administration of doxycycline to eliminate the carrier state.

- Supportive care is targeted at the patient’s presenting clinical signs. Treatments most often target the kidney and include IV fluids with correction of electrolyte and acid/base imbalances.

Client Education and Technician Tips