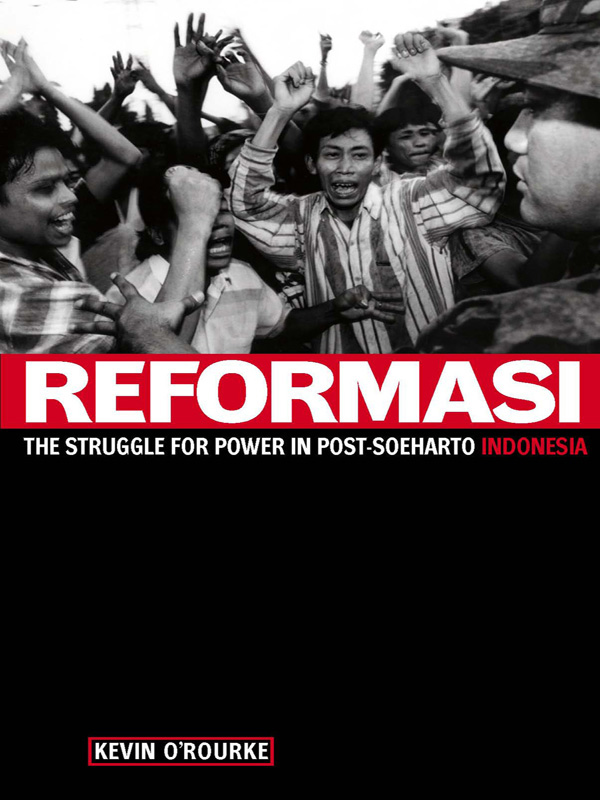

REFORMASI

REFORMASI

The struggle for power in

post-Soeharto Indonesia

Kevin O’Rourke

To the people of Indonesia

First published in 2002

Copyright © Kevin O’Rourke, 2002.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Phone (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

O’Rourke, Kevin, 1971– .

Reformasi: the struggle for power in post-Soeharto Indonesia.

Bibliography.

ISBN 1 86508 754 8.

1. Indonesia – Politics and government – 1998– .

2. Indonesia – Economic conditions – 1998– . I. Title.

320.9598

Set in 10/12 pt New Baskerville by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough

Printed by South Wind Production (Singapore) Private Limited

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

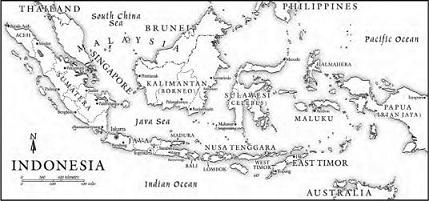

Map of Indonesia

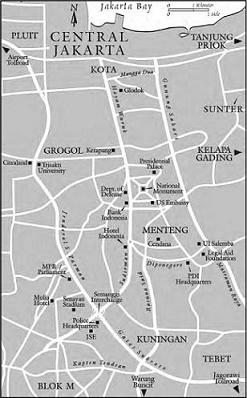

Map of Jakarta

PART I HUBRIS OF THE ELITE

1 Loomings

2 Legacy

3 Crisis of Confidence

4 Predatory State

5 Forcing Reform

6 ‘Closer to God’

7 Impeccably Amok

8 Coup à la Java

PART II TYRANNY OF THE ELITE

9 Zing-a-Bust

10 Photocopying Soeharto

11 ‘Cruelism versus Cruelism’

12 ‘Stay Indoors’

13 Nail of the Universe

14 Oligarchy of the Party Bosses

15 Under-Democracy

16 ‘Slander is Worse than Murder’

17 Heroes of Integration

PART III MELEE OF THE ELITE

18 Acrimony and Larceny

19 Guerilla Politics

20 Shock Therapy

21 East Timor Writ Large

22 ‘Raid Cendana’

23 State of Emergency

Epilogue

APPENDICES

Appendix I Rupiah Exchange Rate

Appendix II Short Biographies

Notes

Bibliography

Glossary

Notes on the text

Preface

Reformasi relates Indonesia’s political events from 1996 through 2001—a period marked by tumult, intrigue, tragedy and mystery.

The book is deliberately broad in scope, and it seeks to provide a ‘holistic’ account—that is, one that integrates subjects (such as banking, Islam and military history) that are too often considered in isolation. Because the events of the period lend themselves to a narrative format, the book proceeds chronologically. I have also sought to capture the drama of this period, but I have tried to avoid melodrama and ‘craftsmanship’. I have therefore aspired to relating the events in a clear and credible style; the intention is to let the events and protagonists convey their own drama.

To support this narrative approach, I have emphasised careful research and annotation. This research effort would not have been possible without several factors: the preceding work of such authors as Adam Schwarz, Michael Vatikiotis, Hamish McDonald, Benedict Anderson, Howard Palfrey Jones and others; the liberalisation of the Indonesian press; and the Internet. The work of Indonesia’s superb foreign press corps was particularly important, as was the Joyo News Service of the indefatigable Gordon Bishop.

The research for Reformasi builds upon my experience of writing the Van Zorge Report, a bi-weekly journal on Indonesian politics and economics. I performed this role from mid-1998 through early 2000, a period that coincided with much of the political tumult. During this time I conducted in-depth interviews with around 60 policy-makers, politicians, generals, Islamic leaders, academics, NGO figures, student activists and journalists. Sarwono Kusumaatmadja, Andi Mallarangeng and Azyumardi Azra were particularly helpful and enlightening; I refrain from naming a great many others because of the sensitive nature of this book, and the country’s continued political uncertainty.

I certainly gained the most valuable insights from innumerable encounters with Indonesians from all walks of life. I first came to Indonesia in 1990, and I have been living in Jakarta for seven years. Throughout this time I have been continuously amazed by the people of Indonesia. Ultimately, it is their graciousness—amid hardship—that inspired me to produce this book. Reformasi takes a hard look at Indonesian politics, but it does so in tribute to a wonderful people who, I believe, deserve better leadership.

Reformasi has been an entirely independent effort in that I’ve received no financial contributions or sponsorship of any sort. However, this book received a tremendous amount of support in terms of encouragement, advice, corrections and input. I am very fortunate indeed that such a large number of extraordinary people were eager to help. Rather than making a difficult effort to rank them in importance, this acknowledgements section will, like the book itself, follow chronologically.

My parents inspired my interest in both writing and government, and my brother Gerald first brought me to Indonesia at age 19. During my undergraduate studies at Harvard, Amir Soltani, Richard Patten and Don Johnston exerted strong influences on me. Jonathan Harris and Gene Galbraith first employed me in the securities industry in Jakarta, and Belinda Tan was an exceptional colleague and friend. And my experience of performing political risk analysis with Dennis Heffernan and James Van Zorge provided invaluable experience.

Gary Goodpaster convinced me to start this project, and important words of encouragement came from Mary Schwarz, Paul Wolfowitz and Adam Schwarz. Mark Hanusz’s support was enthusiastic, astute and crucial. Peter Milne provided editing assistance, instructive ideas and myriad shows of support along the way. Christopher Lingle, John McBeth and John Haseman each provided generously of their time and patience to offer insights, corrections and instruction in their respective fields of expertise: economics, politics and military analysis.

Others who provided important input and encouragement include Chris Bendl, Michael Chambers, James Corcoran, Michael Horn, Kate Linebaugh, Rhea McGraw, David Roes, Frank Shea, John Su, Adnan Tan, Bjorn Thurmann, Roderick des Tombe, Fred Thomas and Edwin Wong. Dean Carignan performed a characteristically thorough and thoughtful critique of the text. My classmate Jean-Jacques Barrow lent his inimitable perspicacity. Arif Sani lent his graphic design expertise and I received help with photos from Tempo’s Pak Priatna, AFP’s Carol Li, Kees Metselaar and the Gamma team. Other friends who have always been reliable are too numerous to mention, but they include Mike Graff, Peter Hogg, Quentin Jordan, Sean MaGuire, Dan Murphy, Jonathan Phillips and Sebastian Sharp. I am especially grateful to John O’Reilly, Arian Ardie and Christine Bader. From Allen & Unwin, Patrick Gallagher and Rebecca Kaiser have been enormously helpful and thoroughly professional throughout.

Having said all this, I alone am responsible for the misinterpretations, inaccuracies and errors that no doubt exist within this text. I have referenced the text with more than 1000 endnotes, but in many cases time constraints prevented me from delving deeper and achieving greater accuracy. I hope that some of the issues that I have been unable to fully answer will eventually be resolved.

I have tried to delineate fact from supposition by consistently denoting the latter as such. Nonetheless, I believe that perfect objectivity is impossible to attain, and the interpretations and analysis in Reformasi ultimately stem from my own sense of what can—and cannot—be reasonably deemed as ‘fair’. I hope I have done justice to a story that richly deserves just that.

A government post: that is everything and all things for one who is neither a farmer nor a tradesman. Wealth may vanish, families may disintegrate and reputations may fall, but the post must be secured. It is not just a livelihood—it’s also prestige, righteousness, self-esteem and a way of life. People fight, pray, fast, slander, lie, work themselves to the bone and back-stab each other, all for the sake of a government post. One would sacrifice anything to obtain it—because with it, all can be restored.

—Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Child of All Nations

A corrupt regime has only one alternative: to stay in power.

—Siswono Yudohusodo

PART I

HUBRIS OF

THE ELITE

1

LOOMINGS

‘Raid PDI Headquarters.’ That simple command, issued by President Soeharto to his security forces in July 1996, triggered the extraordinary political power struggle that would consume Indonesia for years to come.

The raid itself was a simple affair. Several hundred youths who were protesting Soeharto’s rule had barricaded themselves inside a colonial-era mansion in central Jakarta. The building served as the headquarters for Indonesia’s only credible opposition party, the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI). Troops launched an attack at dawn on a Saturday, and by noon they controlled the premises. The event marked a strategic success for Soeharto: it sidelined his main rival, PDI chair Megawati Soekarnoputri, at a critical juncture. It did not, however, constitute a triumph.

The PDI Headquarters raid was not the first time that Soeharto’s ‘New Order’ regime had cracked down on its opponents, but it was close to being the last. The blunt attack made the president appear cruel and desperate. It also dashed hopes for a peaceful political transition, by demonstrating that Soeharto, at age 75, was determined to cling to power by force. For more than 200 million Indonesians the ensuing political struggle would exact exceedingly high costs. The prize was paramount control over the most corrupt state in Asia—and the rules were nonexistent.

After several years, and after the loss of thousands of lives, the forces of change would triumph and Indonesia would become the world’s third largest democracy—or at least so it would appear. In fact, appearances can be misleading in Indonesia, and triumphs can prove ephemeral.

Soeharto was born to a family of impoverished petty aristocrats in rural Central Java, and at the age of seventeen he joined a local military unit under the supervision of the Dutch colonial authorities. It was the eve of World War II. After the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies in 1942, Soeharto served in a similar unit under the Japanese occupiers. The Dutch sought to reclaim their huge colony after the war, but the nationalist leaders Soekarno and Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesia an independent republic. Among the few Indonesians with formal military training, Soeharto became an officer in the republic’s hastily formed army—the ideal place for the savvy youth to realise his ambitions.

Although little more than a loosely organised network of volunteer militias, the army waged a determined guerilla campaign against Dutch forces for nearly five years. This helped win international recognition for the new republic, but Indonesia’s leaders soon faced daunting challenges. Indonesia was blessed with natural resources but three centuries of colonial rule had left the population poor and undereducated. In a dazzlingly diverse archipelago, national unity was sorely lacking. And perhaps most significantly, the political institutions left over from the Dutch colonisers were designed, not to serve the interests of the people, but to uphold the authority of the rulers.

While the young Soeharto steadily rose through the ranks of the army, the political elite affirmed Soekarno, the country’s most popular revolutionary, as Indonesia’s first president. Although his economic ideas were based on a crude form of socialism, Soekarno’s ardent nationalism and respect for pluralism helped unify the country. Meanwhile, he and Indonesia’s other political leaders struggled to build a stable democracy.

The 1945 Constitution, which had been drafted under emergency conditions, was rife with vagaries. A more sophisticated Constitution was therefore introduced in 1950—but whereas the earlier version lacked checks on presidential authority, the second provided for a parliamentary system that proved chronically unstable. Soekarno was reduced to a figurehead, and parliamentary cabinets rose and fell in rapid succession. The country’s first national election, in 1955, failed to bring stability: the vote was fragmented among nearly 30 parties, ranging from communist to Islamist, with socialists and nationalists in between. Two years later Soekarno finally intervened.

Siding with one faction of the military, the president imposed martial law and revived the 1945 Constitution. He used the euphemism ‘Guided Democracy’ to disguise his authoritarian rule. Genuine democracy would not return for more than 40 years.

Amid economic malaise, Soekarno survived through cunning tactics: he mesmerised the nation with his grandiloquence, distracted potential critics with adventurous foreign policy campaigns and encouraged political rivals to fight among themselves. He balanced his presidency between three political forces: military nationalists, Communists and, to a lesser extent, Islamic groups. This formula kept Soekarno in power for nine years, but corruption and economic neglect eventually took their toll. By late 1965 the currency was in free-fall and Indonesians struggled to cope with runaway inflation. Soekarno increasingly associated himself with the Communists, who whipping the political atmosphere into a frenzy. Meanwhile, the president’s relations with the army suffered a corresponding decline.

In September 1965 Soekarno was led to believe that the anticommunist army leadership was poised to launch a coup d’état. He apparently gave his consent to a pre-emptive strike, dubbed the ‘30 September Movement’.2 Two Soekarnoist army officers, Col. Abdul Latief and Lt Col. Untung, mustered several hundred soldiers from a variety of units, including the president’s palace guard. Around 4 a.m. on 1 October, the soldiers raided the homes of seven generals. They abducted and killed six of the targets—the head of the army, his top four assistants and the military’s chief prosecutor.

Controversy persists over who encouraged the attackers to act.3 The standard version (encouraged by the New Order regime) has been that the Communist Party commissioned the murders. However, Latief, Untung and at least one other senior conspirator had previously served in the Central Java Garrison under the command of Maj. Gen. Soeharto. In 1965 Soeharto was based in Jakarta, commanding the army strategic reserve (Kostrad), the military’s premier combat-ready force. As such, he was one of two generals with direct command over troops in the capital; the other was the Jakarta Garrison commander, Maj. Gen. Umar Wirahadikusumah. To have any chance of success, an attack against the army leadership in Jakarta would, presumably, have had to target these two—unless the attackers believed them to be partisans. Both were inexplicably spared.

Latief claimed that he had warned Soeharto about the abductions two days before they took place, and that the conspirators had been assured of the Kostrad commander’s support.4 But on the morning after the murders Soeharto acted swiftly and assertively. With assistance from Kostrad’s intelligence officer, Ali Murtopo, Soeharto mobilised his forces and persuaded the conspirators’ troops to surrender their weapons. When President Soekarno appointed a communist-leaning general to head the army, Soeharto objected and assumed the command himself. He denounced the 30 September Movement as a communist coup attempt and arrested the conspirators. Latief says that he felt betrayed.

A bloody, nationwide anti-communist pogrom ensued. Estimates of the death toll range from 80 000 to 500 000.5 Another 500 000 confirmed or suspected communists were eventually jailed, including Col. Latief, who remained in prison for 33 years. And within a few months Soeharto had wrested control of the government away from the disgraced Soekarno. The New Order had been born.

Many viewed Soeharto’s arrival as a blessing. He imposed order, rectified the economy and eradicated the threat of communism. Indonesians craved stability, and therefore few complained when Soeharto’s party, Golkar, won a landslide victory in the 1971 polls. And the ensuing oil boom, which brought unprecedented riches to Indonesia, also enabled Soeharto to consolidate his grip on power. It was not until the mid-1970s, therefore, that succession worries first began to arise.

Election outcomes were never in doubt: parliamentary polls were rigged to favour Soeharto’s Golkar party, while presidential elections were dominated by Soeharto’s handpicked loyalists in the 1000-member People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR). Nonetheless, the build-up to a parliamentary election was always marked by abnormally high levels of political tension. Before each new presidential term the cagey but inscrutable Soeharto intimated that the upcoming term would be his last. But five years later he would invariably ‘agree’ to serve just one more term.6 Meanwhile, his political longevity hinged on his ability to continue delivering macro-economic growth.

Soeharto portrayed himself as the country’s saviour from communism and regional secessionism, but his most vaunted role was as the ‘Father of Development’. In 1965 Indonesia was the poorest country in Asia, with an estimated 60 per cent of the population—or around 55 million people— living in poverty.7 After Soeharto took over the following year, annual growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) exceeded 6 per cent in all but two of the next 30 years. By 1996 the poverty rate had been cut to 11 per cent, or 22 million people.8 Impressive gains had been recorded in life expectancy, fertility, infant mortality and food self-sufficiency. Perhaps most impressive of all, Indonesia ranked among Asia’s most attractive ‘emerging tiger’ economies—and among the world’s most popular destinations for long-term investment. With land, labour and natural resources in abundance the outlook was bright for sustained growth. But despite these achievements there were reasons for dissatisfaction.

In the latter years of Soeharto’s rule a host of ills came to the fore— such as income disparity, urban squalor, environmental degradation and neglect of human rights. At the root of these ills was Indonesia’s most tenacious problem: corruption. Entire economic sectors were elaborately structured to funnel abnormal profits, or rents, to Soeharto’s family, their inner circle of business partners (or ‘cronies’) and a select few leaders of the powerful military. Rather than serving the public, most functions of the state apparatus were concerned primarily with upholding these rent-seeking structures. Many poor Indonesians were growing gradually better off, but they also confronted mounting injustice in their daily lives.

Therefore, in early 1996, as Soeharto entered the penultimate year of his sixth presidential term, Indonesia’s succession worries were at their highest point in three decades. And while the reasons for opposing Soeharto were stronger than ever, the president had grown out of touch with the population he governed: three out of five Indonesians were too young to have known any other president during their lifetime, and most were eager for change. In contrast, Indonesians young and old were turning their attention to a politician whose lineage had always captivated their imagination: Soekarno’s daughter, Megawati Soekarnoputri.

Aself-proclaimed ‘Sybarite’, Soekarno indulged his senses to excess. He used the former Dutch governor-general’s residence, set in the foothills south of Jakarta, as his presidential palace. There Megawati was raised like a princess—but her luxurious lifestyle changed abruptly at the age of eighteen, when her father was deposed.

While her father remained under house arrest, Megawati tried twice to obtain an undergraduate degree but dropped out both times. Rather than pursuing a career, she chose to marry, but her first husband died in an aircraft crash and her second marriage was annulled. Her father died in 1970 and she finally married her third husband, Taufik Kiemas, three years later.9

Eschewing a professional career, Megawati focused on raising her three children. In the 1980s, however, her husband helped persuade her to enter politics. Megawati had accrued few official distinctions to her name, but her name alone was sufficient distinction for prominence in Indonesian politics. She followed the proud, albeit vague, tradition of her father: secular-nationalism.

Soekarno had founded the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI) in 1927, and youth militias had rallied around its symbol, a fattened bull, during the struggle for independence. PNI stood for prosperity, unity and plurality, but its prime motivating force was Soekarno’s own charisma. After Soeharto’s takeover, PNI was forced to merge with several smaller parties to create PDI. The party entered a long period of decline, eventually becoming a token opposition party whose leaders willingly complied with Golkar and the military. But despite this ignominious role, Megawati joined PDI as a member of parliament in 1987.

The first few years of Megawati’s political career were uneventful, but by the early 1990s a small clique within PDI was growing increasingly outspoken. Rallying around the party’s relatively liberal-minded chair, Suryadi, PDI’s ‘reformists’ waged an unusually aggressive campaign in the 1992 parliamentary elections.10 At rallies across the country, they called for clean government, electoral reforms and presidential term limits. Most outlandishly, PDI demanded multiple candidates in the 1993 presidential election, to be held in the MPR (which consisted of all 500 parliamentarians, plus 500 appointed representatives). But in addition to the unusually daring platform, PDI’s main draw was Soekarno’s benevolent-looking daughter.

Exactly how much electoral support PDI mustered in the 1992 election remains uncertain: the elections were far from free or fair. The Golkar-controlled election authorities credited Golkar with 68 per cent of the national vote—a figure typical of the official results of past elections. The following year the MPR dutifully handed Soeharto his sixth presidential term. But while PDI’s campaign looked like a failure on the surface, Suryadi’s party had at least voiced criticism; at the time, this alone was an important achievement. And by eliciting a stern response from Soeharto, PDI set in motion a train of events that would shape the nature of Indonesian politics for years to come.

Soeharto’s style of rule was apparently shaped by his upbringing. He was steeped in traditional Javanese values, which extol harmony and emphasise deference to elders. He was trained by the Dutch and Japanese militaries, which were naturally preoccupied with imposing security. And as an army officer, Soeharto joined or led campaigns to quell such threats as local uprisings, communist rebellions and regional secession movements. It seemed that a product of these cumulative experiences was a fixation on stability and order. Soeharto displayed little tolerance for dissent, and his inclination was to repress opposition before it could gain strength. Immediately after surpassing his re-election hurdle in 1993, this is precisely what he proceeded to do.

Over time, Soeharto had grown adept at defending his regime. He developed a host of instruments that he could use to punish his critics and opponents: among others, these included the police, the attorney general’s office and the courts. But the most serious threats to the regime were dealt with by the military.

Despite a proud history, Indonesia’s military gradually evolved into an instrument for upholding Soeharto’s authority.11 By the 1990s the military had become Indonesia’s most powerful political institution by far. It played an overt political role that was rationalised through its so-called ‘dual-function’ doctrine. This maintained that the military was the protector of the nation, and was obliged to contribute its institutional resources to the nation’s development. In fact, the military’s dual function was an anachronism that had gone badly awry.

The military had been a politically motivated force from its inception. In the struggle against the Dutch the newly formed officer corps included substantial numbers of Javanese, priyayi aristocrats, through whom the Dutch had governed for over two centuries. Once independence had been won, the natural inclination of these priyayi was to carry on governing as they had before—but on their own behalf, rather than on behalf of the Dutch.

As the Communist Party gained strength in the late 1950s, anticommunist generals sought to counter the threat by seconding military personnel to civil service posts throughout the government bureaucracy. President Soeharto, however, sustained this practice long after the threat of communism had receded. Rather than countering communism, the military was countering political opposition to Soeharto. By 1993, thousands of active and retired officers served at all levels of government, including several hundred generals in the cabinet, parliament, Supreme Court, Golkar, gubernatorial offices and state-owned enterprises.12

Even more important than the military’s civil service role was its ‘territorial system’—a force structure that made the Indonesian army look as if it was occupying its own country. The army maintained a physical presence at almost every administrative level of the state, from regional garrisons commanded by two-star generals to village-level posts manned by sergeants.13 These ‘territorial commanders’ typically wielded paramount authority in their respective districts, and through them the military wielded the bulk of its political clout.

The priority attached to the military’s overt political role was readily apparent from a glance at its command structure. The military’s top post was the armed forces commander, a four-star officer who presided over the chiefs-of-staff of the four services (army, navy, air force and police). But reporting directly to the armed forces commander were two crucial three-star officers: the commander of the army strategic reserve (Kostrad); and the kaster, or chief-of-staff for territorial affairs.14 While the command of Kostrad was purely a combat role, kaster was almost exclusively political. The kaster formulated the military’s policies on ‘socio-political’ events and intervened, where necessary, to guide developments in Soeharto’s favour.

The chief political instruments at the kaster’s disposal were the military’s powerful strategic intelligence agency (Bais) and the Special Forces. Bais had an extensive reach: it maintained a network of intelligence operatives attached to all but the lowest levels of the territorial system.15 The agency focused on internal threats to the regime, such as political dissidents or regional secessionist movements. To carry out covert operations against these threats, Bais would typically work with the Special Forces, an elite commando outfit with special ‘anti-terrorist’ capabilities.

Soeharto therefore possessed formidable and well-honed instruments with which to confront challenges to his authority. Because numerous threats had been surpassed in the New Order’s first 25 years, it seemed a relatively simple matter when Soeharto turned his attention to the nettlesome PDI in 1993. As he had done so often before, Soeharto summoned his armed forces chief, Gen Feisal Tanjung, and discussed what he wanted done.

After each presidential election Indonesia’s three political parties installed new leaders in special party congresses. These were well-rehearsed affairs that were full of ‘guidance’ from above—particularly PDI’s 1993 congress. When the party convened in mid-year to re-elect Suryadi as chair, Tanjung intervened. His subordinates, including the kaster and various intelligence officers from Bais, approached individual PDI members and delivered tailored messages: Suryadi’s supporters were issued threats, while his opponents were given inducements.16 The process dragged on for several months, but PDI finally voted to oust Suryadi. In the process, however, Tanjung’s men suffered a setback.

Either through a bargain or a blunder, the military allowed PDI’s reformers to replace Suryadi with a potentially more potent leader: an offspring of Soekarno. But rather than the eldest son, Guntur, or the politically active daughter, Rachmawati, PDI settled on the more demure Megawati. But while she was deemed the least aggressive sibling, Megawati was still a threat to Soeharto—by virtue of her pedigree alone. In effect, the military’s meddling had backfired.

With crucial support from a handful of reform-minded PDI colleagues, Megawati used her position as party chair to criticise the government and make strident calls for ‘reformasi’—i.e. political and economic reforms. Although the tightly controlled press rarely publicised her statements, Megawati’s appeal nonetheless grew throughout 1994 and 1995—particularly on the island of Java, Indonesia’s political heartland and home to 60 per cent of the national population. By early 1996 it was clear that PDI would make the following year’s parliamentary election the most exciting contest in decades. As usual, PDI had no hope of securing a victory in the rigged polls, but Megawati’s campaign appearances alone promised to generate a groundswell of anti-government sentiment.

Soeharto was in a difficult predicament. Letting Megawati campaign would be humiliating, but arresting the daughter of a national icon would be foolhardy. He therefore settled on a middle course: he would depose Megawati as PDI chair, just as he had done with Suryadi three years before. Megawati’s term was not yet halfway completed, but it would not be the first time that Soeharto had illegally removed a critic from the political limelight. This time, however, the stakes were far higher than ever before.

Again Soeharto turned to Tanjung. At 57, the rotund, mustachioed general was already two years beyond mandatory retirement age, but Soeharto had retained him as armed forces commander in light of his able service. Tanjung had developed a wide-ranging reputation for greed and malice, but he was a ruthless hardliner who could read political trends with skill.

Having sidelined the officers responsible for the blunder three years before, Tanjung delegated this project to his new kaster and fellow hardliner, Lt Gen. Syarwan Hamid. A tough, chain-smoking Sumateran, Hamid was destined to crop up repeatedly over the next few years in a host of different roles. At the time, however, he was known primarily as the general who had recently jailed several labour leaders, while issuing stern warnings about the latent threat of a communist-inspired ‘new left’.17 Hamid was stout and balding, though he compensated for a lack of martial bearing with skills as a cunning tactician. He put these skills to use in forming a plan to deal with Megawati.

Hamid perceived that a significant number of PDI delegates could be persuaded to do his bidding. Although the party leadership contained a number of dedicated reformists, PDI’s rank-and-file was riddled with more pliable figures. But the key to Hamid’s plan was his choice as Megawati’s replacement. He realised that to insert a political unknown as party chair would only make the military’s meddling all the more transparent. He therefore called on a figure who possessed considerable credibility as a reformer: Suryadi, the party chair whom the military had worked so hard to oust just three years before.18

Hamid told Suryadi that if he agreed to obey orders he would be allowed to return from forced retirement and reclaim his old post as party chair, usurping Megawati. Like many within his party, Suryadi proved willing to bend. Some also suspect that he was threatened into complying. In any event, on Hamid’s instructions, Suryadi mustered a ‘turncoat’ faction within PDI. An extraordinary party congress was scheduled for June 1996.

Tanjung and Hamid chose to hold the congress in Medan, the principal city of their native Sumatera. Tanjung, in his youth, had reputedly worked for Medan’s portside racketeers as a local hoodlum.19 Such hoods were called ‘preman’—a word coined in early colonial times to refer to an ex-slave, or ‘free man’, who resorted to crime to survive.20 As will be seen, preman still played prominent roles in Indonesia; Tanjung and Hamid were just a few of the military officers who made frequent use of preman gangs to carry out underhanded ‘regime maintenance’ chores. In Medan, Tanjung and Hamid would have few security concerns while they performed the most high-stakes ‘regime maintenance’ chore of their careers.

Breaking their usual habit of keeping a low profile, both generals appeared at the Medan congress and figured prominently in the proceedings. Megawati and her supporters were prohibited from attending the congress, which achieved a quorum only by including new members whose right to take part was dubious at best. In businesslike fashion the congress voted to cut short Megawati’s term as party chair and reinsert Suryadi.21 The procedures violated the party’s articles of confederation, but Tanjung and other cabinet officials were on hand to endorse the decision.22 Megawati was rendered powerless, while Soeharto achieved a long-awaited triumph—or so it seemed at the time.

It soon became clear that Megawati’s ardent followers were unwilling to concede defeat. In particular, some 200 student activists refused to leave the premises of PDI’s headquarters. The building they occupied was a large house situated on Jalan Diponegoro—a noisy but stately avenue on the edge of Jakarta’s most prestigious residential neighbourhood, Menteng.23 The students maintained a nonstop vigil in front of the building, denouncing the Medan congress and Suryadi’s turncoat faction. Fearing retaliation from the authorities, Megawati urged the youths to abandon the headquarters and fight another day. Instead, their protest movement grew in size. Attracting a wide assortment of courageous government critics, the students erected a podium on the footpath where democracy activists delivered fiery speeches to the assembled crowd.

The gatherings on Jalan Diponegoro quickly grew to become the most strident, and embarrassing, protests in the history of Soeharto’s rule. The protests also jeopardised the already dubious validity of the Medan congress: not until Suryadi physically occupied the headquarters building could he plausibly claim PDI’s chair. But the students refused to leave. Police units sometimes dispersed the crowds on the street; the students would simply recede inside and re-emerge later.

Hamid urgently needed a solution. He met repeatedly with intelligence officials, particularly a young general who, as head of Bais’s powerful Directorate A, was directly responsible for the president’s physical and political security: Brig. Gen. Zacky Anwar Makarim.24 Another one-star general involved in the planning was Brig. Gen. Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.25 Like Hamid, Makarim and Yudhoyono would play critical roles in the years to come. But in July 1996 the generals were faced with a thorny problem. They finally determined that to end the protests, install Suryadi and seal the results of the Medan congress, the students would have to be ousted by force.

Hamid’s problem, however, was that a direct assault by security forces would be unseemly. Military rhetoric held that the security forces were the impartial guardians of the nation’s interest. To be seen intervening in practical politics—or, worse still, taking sides in an internal squabble of an ostensibly independent opposition party—would make a mockery of the military’s vaunted neutrality. Moreover, an overt military attack would only reinforce public sympathy for Megawati—at the expense of the military and Soeharto.

Hamid and Makarim therefore turned to a plan that was standard procedure in such situations: the use of preman in the place of regular troops.26 By the 1990s it was common for military officers and entire units to provide ‘backing’, or protection, for illicit businesses run by mafia-style gangs.27 The gangs would be allowed to smuggle, run casinos, manage brothels or deal drugs—and the military would receive a cut to complement its meagre budget or to simply enrich its top officers. When necessary, the military could also rely on these gangs to provide manpower for special jobs.

Indonesia’s surplus of unskilled labour meant that gangsters could easily recruit hundreds of young thugs whenever the military wanted to avoid a direct clash with civilians. July 1996 was one of these instances. When it became clear that the pro-Megawati students were not going to be coaxed or cajoled into surrendering, Hamid decided to recruit preman and disguise them as angry partisans of Suryadi. Hamid therefore called on Yorrys Raweyai, arguably Indonesia’s most prominent underworld figure.

Raweyai was a native of Indonesia’s largest, most remote and most underdeveloped province: Irian Jaya, on the western half of the island of New Guinea. The 45-year-old Raweyai, who was of mixed Papuan and ethnic-Chinese descent, had distinguished himself by overseeing protection rackets and collecting debts for Irian Jaya’s logging and mining interests, most of which involved Soeharto-family cronies.28 By 1996 Raweyai had taken over operational control of Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth). Ostensibly the youth wing of Golkar—and ostensibly dedicated to upholding the state ideology, Pancasila—the organisation was widely viewed as a state-sanctioned crime syndicate.29 In mid-July, Raweyai reportedly brought several dozen Pemuda Pancasila members to a field in Menteng, where they conducted a training drill under Hamid’s supervision.30

Soon afterwards, Soeharto summoned senior military leaders to his residence on Jalan Cendana, on the opposite side of Menteng from Jalan Diponegoro. Attending the meeting were Tanjung, Hamid and at least six other senior generals.31 Soeharto expressed his vexation with the incessant protests being staged on Jalan Diponegoro. According to three of those present, Soeharto issued an unmistakable order that the protests be put to a stop; Tanjung then formulated the detailed plan.32

Following the Cendana meeting, control over the operation was delegated to the Jakarta Garrison—the military command that co-ordinated security measures in the capital. Yudhoyono, the garrison’s second-in-command, chaired a crucial planning session on 22 July. In attendance were Makarim, Suryadi aides from PDI and several garrison officers.33 Immediately thereafter, Yudhoyono’s subordinates began contacting preman bosses in the Jakarta area to recruit manpower.

As Raweyai later explained: ‘I received a telephone call on 26 July from the intelligence staff of the Jakarta Garrison.’34 He was instructed to supply around 100 preman for an operation that night. The staging ground was the Artha Graha office building, owned by a financier of the military. In addition to Raweyai’s men, around 100 thugs from other gangs also arrived, plus more than 100 regular garrison troops dressed in plain clothes. In addition, six companies of police mobilised before dawn to place cordons across the streets surrounding PDI Headquarters.35

‘Around 4 a.m. on 27 July,’ said Raweyai, ‘Pemuda Pancasila members were sent to the home of the women’s affairs minister [next to PDI Headquarters on Jalan Diponegoro]. They were given red PDI shirts which they were forced to wear.’36 This detail was meant to create the impression that the impending attack was strictly an internal party affair, conducted by supporters of Suryadi’s faction.

Inside the headquarters building on Jalan Diponegoro, the pro-Megawati students braced for an attack. Their number had been reinforced to nearly 400. They had constructed barricades around the compound, but they were not optimistic about being able to withstand an assault. As dawn broke, the ‘Suryadi supporters’ began their attack.

The preman and soldiers started by hurling rocks, bricks and molotov cocktails, hoping to frighten the students into surrendering. When this failed, small groups of attackers clambered over the compound walls. The professional soldiers and street-hardened thugs should have overpowered the university students but, perhaps because they only launched piecemeal attacks, the attackers were kept at bay for over two hours. Finally the security forces abandoned the pretext of an internal PDI dispute and committed a company of baton-wielding riot police.37 This turned the tide.

When the police poured into the compound, a portion of the students exited over the building’s rear wall and were allowed to flee. The remainder stayed to fight, but the police, together with the ‘Suryadi supporters’, gained ground. One by one, room by room, the youths succumbed to kicks, blows and beatings from batons. Two were killed, 181 injured and 124 arrested.38 By 9 a.m. the fighting at PDI Headquarters was over—but now an even bigger battle was brewing nearby.

Located just across the railroad tracks from Menteng, and less than a kilometre from PDI Headquarters, was a district of Jakarta known as Matraman. The area contained several poor, densely packed neighbourhoods called kampung, and as morning wore on, news of the nearby melee spread rapidly through the narrow alleyways and back streets. All morning, boys and young men poured out of the neighborhood to assemble on the wide boulevard of Jalan Matraman Raya. By midday the crowd numbered more than 10 000, and the youths surged up against the police barricades that blocked off Jalan Diponegoro.

Although a small detachment of police sought to disperse the youths, television cameras captured the cane-wielding officers retreating pell-mell amid a hail of rocks and stones. The burgeoning crowd quickly turned into a riotous mob—vandalising banks, showrooms and shop-houses. The rioters destroyed the local police station and set fire to a nearby bank, sending thick plumes of smoke high into the sky—which, in turn, attracted yet more youths from more distant kampung.

Better equipped police and military units finally arrived late in the afternoon. Using water cannons and tear gas, these units dispersed the crowd, but the most famous images of the riot were video footage of police and soldiers using canes to batter youths who were cowering on the ground. In the end, five people died and 149 were injured. Twenty-three went missing and were never found.39

The Matraman riot revealed that, behind its tranquil facade, Indonesian society harboured deepseated animosity toward the New Order regime. For Soeharto the Matraman unrest was the worst of his entire presidency—and it was also a harbinger of what lay ahead. At the time, however, Soeharto apparently overlooked the riot’s significance and focused on the PDI raid, which he regarded as a success.

As Raweyai later noted, to have taken part in the raid was a source of distinction.40 The key figures involved received prompt promotions: Makarim took command of Bais, Yudhoyono rose to major general and Raweyai was appointed to the MPR.41 The commander of the Jakarta Garrison, Maj. Gen. Sutiyoso, soon obtained one of the government’s most coveted posts: governor of Jakarta.

Soeharto’s satisfaction was not without reason: with parliamentary elections just around the corner in June 1997, Megawati had been deprived of her political vehicle. And with his main source of political opposition neutralised, Soeharto could turn his attention to the only other figures who posed any real threat. These were Indonesia’s two chief religious leaders: Abdurrahman Wahid and Amien Rais.

In the 1920s, Hasyim Ashari propounded a religious doctrine that synthesised Java’s indigenous mysticism with Middle Eastern Islam.42 The doctrine itself was not new, but Ashari’s contribution was to organise a network of pesantren, or traditional religious boarding schools that emphasised moral values. His movement quickly developed into a grassroots socio-religious organisation known as the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), or ‘Revival of the Religious Scholars’. Ashari’s son, Wahid Hasyim, oversaw NU’s expansion from its stronghold in East Java to other parts of the densely populated island. He became minister of religion in 1950, but three years later died in a car crash. His son, Abdurrahman Wahid, was thirteen years old at the time.

Reared in pesantren, Wahid pursued his higher education in the 1960s in Cairo and pre-Baath Iraq. He was always destined to play a prominent role within NU: familial ties figured prominently in NU’s complex organisational hierarchy and Wahid’s exalted lineage provided him, in effect, with royal status in NU circles. Upon his return to Indonesia in the early 1970s, Wahid studied and lectured in a host of pesantren. It was during this time that he refined the philosophy that would guide his later career: respect for religious pluralism.

Given that the Indonesian archipelago was arguably the world’s most culturally diverse country, Wahid adamantly believed that tolerance of religious differences was essential for Indonesia’s national unity. He applied this principle to NU: rather than an ‘exclusive’ institution that championed rigid dogma, Wahid wanted NU to be an ‘inclusive’ organisation that remained tolerant and openminded. This message resonated with the membership of NU—after all, NU professed a ‘syncretic’ Islam that incorporated elements of Javanese mysticism, as well as ancient Hindu and Buddhist traditions.43 Given his pedigree and energetic campaigning, Wahid quickly emerged as NU’s pre-eminent leader. In 1984, at age 44, he attained the organisation’s top administrative post as NU chair, a position he would hold until 1999.

By the mid-1990s NU claimed nearly 40 million members.44 Although this figure was exaggerated, NU was indisputably the largest Islamic organisation in Indonesia. And because Indonesia was the world’s largest Muslim country, NU may also have been the world’s largest Islamic group. Although Wahid generally refrained from taking an active role in politics, the sheer size of his organisation—and his revered status among NU’s grassroots membership—made him a consequential political figure by default.

Wahid was not, however, without rivals. Despite NU’s size, the bulk of its members were confined to rural Java. Elsewhere, in the cities and in the Outer Islands, the dominant organisation was Muhammadiyah.

Founded in 1912, Muhammadiyah mirrored Middle Eastern movements that sought to reconcile Islam with an increasingly modern and secular world. In religious terms, this involved the promotion of Middle Eastern orthodoxy in place of indigenous beliefs. In educational terms, Muhammadiyah emphasised the teaching of science and technology rather than liberal ‘Western’ philosophy.45 And although Muhammadiyah disavowed any involvement in politics, the organisation was, in fact, intensely political.

Like NU, Muhammadiyah was large—by the mid-1990s it was claiming nearly 30 million members—but its political significance was due to more than size alone. It was the chief proponent of Islamic modernism, and the modernist movement had always harboured those who pursued expressly political goals. These goals varied widely. One general aim was to simply improve governance by contributing ethical values derived from Islam. Many modernists, including Muhammadiyah leaders, believed that this laudable goal could be achieved without offending nominal Muslims or religious minorities. Others, however, had more ambitious goals.

Some of the more ardent proponents of Islamic modernism rejected the separation of temporal and religious authority as illogical, and they therefore hoped to draw the two closer together. These ‘political Islamists’ varied widely. Some sought a limited Islamicisation of specific branches of the government, while others wanted a wholesale switch to a state based on Islamic law. Some sought to move swiftly—even militantly—while others pursued a gradual approach.

‘Political Islam’ was therefore a diffuse movement. It never appealed to more than a minority of modernists and it was never explicitly endorsed by Muhammadiyah. Nonetheless, it had affected national politics since the founding of the republic in the late 1940s. And by the latter stages of Soeharto’s rule it was playing a particularly important role: it was the principal lever that Soeharto used to pry apart Indonesia’s two largest Islamic organisations. This is because political Islam—and modernism in general—was regarded as an alarming threat by Abdurrahman Wahid.

W