Second Edition

Praise for Social Causes of Health and Disease

“In this revised edition William Cockerham develops a strong and challenging case for the role of social factors in health and disease. Drawing on the latest and most important research, Social Causes of Health and Disease will stimulate debate and discussion in equal measure - essential reading for students and researchers alike.” Michael Bury, Royal Holloway, University of London

“This second edition of William Cockerham’s acclaimed book updates his argument about the social causes of disease, drawing on the latest research from both the US and UK. His argument about the direct causal effects of social factors on health and disease is compelling and will be of considerable interest to students and researchers of both sides of the Atlantic.”

Jonathan Gabe, Royal Holloway, University of London

Second Edition

polity

Preface

For more than half a century, medical sociology has evolved as a subdiscipline of mainstream sociology. At times it was more beholden to medicine than sociology for its support, even though the field became one of the most popular sociological specialties. Time invariably brings change and medical sociology has indeed changed since its inception. For example, the old claim that medical sociology is atheoretical has been definitively quashed; there is now even a specialized journal (Health and Social Theory) on the topic. Sociological theory, in fact, has become one of the most important and distinctive research tools in the field. Moreover, medical sociology has positioned itself to provide even more precise and extensive analyses of the social aspects of health and disease. The first edition of this book represents one of the first treatises of the twenty-first century describing a new direction for research that will likely be commonplace in the not-to-distant future: the social causation of health and disease. This edition follows up on that argument. The book begins with the notion that society can make you sick and then explains the ways in which this happens.

The revised book is a further extension of a lecture I presented at the University of Montreal on a cold, grey, slushy, wet Canadian afternoon in January, 2006. This presentation was part of the university’s “Alexis de Tocqueville: Questions on American Society” lecture series. Arnaud Sales of the sociology department and Andrée Demers of Groupe de recherche sur les aspects sociaux de la santé et de la prevention (GRASP) were wonderful hosts. In preparing for this lecture, I wanted to look forward in discussing medical sociology and focus on the future rather than the present or past. It seemed clear that the current state of theory and developments in statistics for multilevel analyses will allow medical sociologists to better assess the effects of different layers of social structure on the health of individuals. This not only forecasts a greater concern with structure in our future work, but will also permit us as a community of scholars to uncover the social mechanisms that cause health and disease. This book represents an early step in that direction.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of several people, although the conclusions expressed are my own. Emma Longstaff , the sociology editor for Polity in Cambridge, England, provided many helpful suggestions and a high level of professionalism in her work concerning this manuscript, as did her replacement Jonathan Skerrett. Their influence led to producing a manuscript that will hopefully bridge the Atlantic as it relies heavily on both North American and British research literature. I would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Ann Bone and Belle Mundy in the production and copy-editing of the manuscript.

Mike Bury, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Royal Holloway College London, was a stalwart critic as a reviewer for Polity on the first edition. His detailed comments helped sharpen the book’s thesis and he went beyond reviewing to make many cogent and thoughtful suggestions that proved to be extraordinarily helpful. I would like to additionally thank an anonymous American reviewer for her comments and reminders to make the book appealing to students. Brian Hinote and Jason Wasserman, both doctoral students in medical sociology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, were an especially competent sounding board when working through some of the issues discussed in the first edition. Carrie Betcher was an efficient replacement for the second edition. I would like to thank Olena Hankivsky (Simon Fraser University) for a clarification and three anonymous reviewers for Polity who provided helpful comments. Ferris Ritchey and Mark LaGory, in their former positions as sociology department chairs at UAB, made sure that I had the time and support to work on the manuscript. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Cynthia, for her continued support. Time and time again, she has proven herself to be an intelligent, insightful, and wry observer of the human social condition.

William C. Cockerham

Schopenhauer’s saying, that a human can very well do what he wants, but cannot will what he wants, accompanies me in all of life’s circumstances …

Albert Einstein – in a 1928 speech to the German League for Human Rights and repeated in his “My Credo,” 1932

1

The capability of social factors to make people ill seems to be widely recognized by the general public. Ask people if they think society can make them sick and the probabilities are high they will answer in the affirmative (Blaxter 2010). Stress, poverty, low socioeconomic status, unhealthy lifestyles, and unpleasant living and work conditions are among the many inherently social variables typically regarded by lay persons as causes of ill health. However, with the exception of stress, this view is not expressed in much of the research literature. Studies in public health, epidemiology, behavioral medicine, and other sciences in the health field typically minimize the relevance of social factors in their investigations. Usually social variables are characterized as distant or secondary influences on health and illness, not as direct causes (Link and Phelan 1995, 2000; Phelan et al. 2004). Being poor, for example, is held to produce greater exposure to something that will make a person sick, rather than bring on sickness itself. However, social variables may be more powerful in inducing adversity or enrichment in health outcomes than formerly assumed. Society may indeed make you sick or conversely, promote your health.

It is the intent of this book to assess the evidence indicating that this is so. It is clear that most diseases have social connections. That is, the social context can shape the risk of exposure, the susceptibility of the host, and the disease’s course and outcome – regardless of whether the disease is infectious, genetic, metabolic, malignant, or degenerative (Holtz et al. 2006). This includes major afflictions like heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, stroke, cancers like lung and cervical neoplasms, HIV/ AIDS and other sexually-transmitted infections, pulmonary diseases, kidney disease, and many other ailments. Even rheumatoid arthritis, which might at first consideration seem to be exclusively biological, is grounded in socioeconomic status, with lower-status persons having significantly greater risk of becoming arthritic than individuals higher up the social scale (Bengtsson et al. 2005; Pederson et al. 2006). Consequently, the basic thesis of this book is that social factors do more than influence health for large populations and the lived experience of illness for individuals; rather, such factors have a direct causal effect on physical health and illness.

How can this be? Just because most diseases have a social connection of some type, does not necessarily mean that such links can actually cause a disease to occur – or does it? Social factors such as living conditions, lifestyles, norms, social values, and attitudes are obviously not pathogens like germs or viruses, nor are they cancer cells or coagulated clots of blood that clog arteries. Yet, quarantined in a laboratory, viruses, cancers, and the like do not make a person sick. They need to be exposed to a human host and assault the body’s physiological defenses in order to be causal. However, assigning causation solely to biological entities does not account for all of the relevant factors in a disease’s pathogenesis, especially in relation to the social behaviors and conditions that bond the person to the disease in the first place. Social factors can initiate the onset of the pathology and in this way serve as a direct cause for a number of diseases. One of many examples is smoking tobacco.

Smoking is associated with more diseases than any other health-related lifestyle practice (Cockerham 2006b; Jarvis and Wardle 1999). Autopsies on heavy smokers show lung tissue that has been transformed from a healthy pink to gray and brownish white in color. Smoking also affects the body in other ways, such as damaging the cardiovascular system, causing back pain, and producing increased risk of loss of cartilage in knee joints through osteoarthritis. The physiological damage caused by smoking cigarettes is due to the irritant and carcinogenic material (“tar”) released by burning tobacco into smoke that is inhaled in the lungs and enters the blood stream where it is spread throughout the body. Persons who die from lung cancer are increasingly less able to breathe and feel suffocated as their lungs lose the capacity to transfer oxygen to the blood.

In Britain, some 120,000 people die annually from smoking. In the United States, with its much larger population, about 440,000 Americans die each year from smoking-related causes, including some 200,000 dying from lung cancer and another 200,000 from adverse effects on the cardiovascular system. Smoking promotes heart attacks and strokes, narrows and hardens arteries, damages blood vessels and causes them to rupture (aneurysms), and brings on high blood pressure. Habitual smoking regularly results in premature death, with a man in the US losing 13 years of life on average and a woman 14.5 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002; Pampel 2009).

How do social variables enter into this disease pattern in a causal role? At one level it looks like the causal factors are all biology: tar in smoke causes cancer and impairs blood circulation. But tar by itself is not causal. It has to enter the human body to have any effect. What is ultimately causal is the human being – both as a host inhaling the smoke and as a manufacturer of a smoking-prone social environment. There is a social pattern to smoking that indicates tobacco use is not a random, individual decision completely independent of social structural influences.

However, smoking and other risky behaviors have not been viewed in a broad social context by researchers as much as they have been characterized as situations of individual responsibility. If people wish to avoid the negative effects of smoking on their health, it is therefore reasoned that they should not smoke. If they choose to smoke, what happens to them is no one’s fault but their own. This victim-blaming approach, argue Martin Jarvis and Jane Wardle (1999), is not helpful, because it does not explain why people, especially those from socially disadvantaged circumstances, are drawn to poor health habits like smoking and the types of social situations that promote this behavior. Today, smoking is unusual among persons at the higher and middle levels of society and is concentrated among people toward the bottom of the social ladder. Persons in higher socioeconomic groups were the first to adopt smoking in the early twentieth century and other social classes followed, but growing publicity about the harmful effects of cigarettes in the 1960s led to a shift in smoking patterns over time as better educated and more affluent groups began avoiding the practice (Antunes 2011; Narcisse et al. 2009; Pampel 2009).

The social process of becoming a smoker is described by Jason Hughes (2003) who determined that confirmed smokers pass through five stages in their smoking career: (1) becoming a smoker, (2) continued smoking, (3) regular smoking, (4) addicted smoking, and, for some, (5) stopping smoking. Based on interviews with both smokers and ex-smokers in Great Britain, Hughes determined that the first experience people have with smoking cigarettes in the initial stage of becoming a smoker is typically unpleasant. The smoker usually feels nauseated. One respondent told Hughes (2003: 148) that she really did not like her first cigarette, describing it as “foul.” This raises a crucial question: If the first experience is unpleasant, why do people continue? Hughes’s answer is that people learn how to smoke by having other individuals interpret the experience for them and tell them how to distinguish the desired sensations from the undesirable. Specifically, they are taught how to inhale properly and pull the smoke into their lungs. One woman in the Hughes (2003: 149) study reported on what it was like being a smoker when she first started: “… it was quite exciting. I thought I’d grown up! It was something new. And it is a skill that you have to learn to do it properly so that people don’t say, ‘she’s not inhaling properly, she’s not smoking.’ You have to learn how to do it.”

Hughes explains that, initially, smoking is a social activity carried out with other people. It typically has its origins in adolescent peer groups, in which teens imitate adult or older teen behavior. Teens smoke to “connect with,” “fit in,” and “impress” their friends. Joy Johnson and her colleagues (Haines, Poland, and Johnson 2009; Johnson et al. 2003) studied teen smoking in Canada and found that adolescents are more socially than physically dependent on cigarettes in the beginning.

The social setting, namely relaxing with peers, caused smoking more than wanting to inhale tobacco smoke. Often the teen did not smoke when friends were not around. But when friends were present, new smokers used cigarettes primarily to connect with them socially, project an image of being “cool,” and express solidarity. Three teenagers in the Johnson et al. (2003: 1484–6) study analyzed smoking in their peer groups this way:

Like it [smoking] is a social aspect of their life that they have become dependent on, as much as the nicotine, you know. I think almost the social setting of it is something that is somewhat addictive itself. (17-year-old female)

People don’t really have to smoke, but they do it anyways to like fit in, or whatever, and they smoke to put out an image to people. (17-year-old male)

It’s more what you will do to fit in, not what you will do to smoke, because you may not actually want to smoke. (16-year-old male)

Reports such as these support Hughes’s (2003) contention that the beginning stage of becoming a smoker is principally a social experience. Not only are the techniques learned within peer groups, but the act of smoking is used to promote social relationships, reinforce personal bonds, and express group affiliation. Soon the adolescent smokers also learn to recognize the effect of nicotine on their emotions. Smoking helped them feel calm and reduced anxiety; it could also ease depression, sadness, fear, loneliness, and anger. Some novice smokers found they could like the taste and others felt smoking was a sign of transition to an adult identity. While most adolescents likely try smoking at some point in growing up, the majority do not continue. For those that do, however, they enter the second stage of smoking described by Hughes, that of continued smoking. Here the beginning smoker starts smoking more frequently as part of a consistent pattern of behavior. These smokers continue to use cigarettes to socialize, but also for other reasons like relaxation, pleasure, alleviating stress, or helping their concentration. They also smoke when they are alone, instead of just when they are with other people. They begin recognizing themselves as smokers and find they have a growing sense of dependence on the addictive qualities of nicotine as they move into the third stage of regular smoker in which smoking becomes a lifestyle habit that leads to the fourth stage of addicted smoking in which the smoker has to smoke a cigarette just to feel “normal.” As one addicted smoker (Johnson et al. 2003: 1488) put it: “It’s gone beyond maybe wanting it or enjoying it, but at this point, your body is addicted to it, and no matter what, you couldn’t get through the day without either thinking about it or feeling you need a cigarette” (19-year-old female).

The causal chain leading to a smoking-related disease in this scenario would look like the following: social interaction among peers leads to smoking which, when continued over time, results in regular smoking and addiction to cigarettes that has a high probability of eventually producing health problems. While perhaps not all smokers begin smoking with someone else’s assistance, it appears that almost all do. Moreover, even when smoking is self-taught, the novice smoker confirms the practice in the company of other smokers (Haines, Poland, and Johnson 2009). Growing up in a household where one or both parents smoke, having a spouse who smokes, and regularly socializing with smokers are other social situations promoting smoking. In practically all cases, smoking is behavior initially acquired in the company of other people (Cockerham 2006b). The origin of this causal chain is social. Removing the social element breaks the chain and prevents the disease process from occurring. Since smoking typically begins in social networks, it is logical that such networks can also curtail its use. This possibility was considered by Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler (2008) who investigated smoking patterns in densely interconnected social networks in the Framingham, Massachusetts, heart study. They found that whole clusters of closely connected people had stopped smoking more or less together. This was due to to collective pressures from their network, coming mainly from spouses, siblings, other family members, and co-workers who were close friends. As a social and therefore shared behavior, Christakis and Fowler determined that smokers were more likely to quit when they ran out of people with whom they could easily smoke. They (Christakis and Fowler 2008:2256) concluded “that decisions to quit smoking are not made solely by isolated individuals, but rather they reflect choices made by groups of people connected to each other both directly and indirectly.” Those who remained smokers were pushed to the periphery of the networks as the networks themselves became increasingly separated into smokers and non-smokers. Consequently, to minimize or deny the role of social processes in the onset and continuation of health problems stemming from smoking renders any other explanation incomplete. In this scenario the social is clearly causal.

Smokers also typically have less healthy lifestyles across many related behaviors, such as poorer diets, less regular exercise, and more problem drinking (Cockerham 2005; Edwards et al. 2006; Laaksonen, Prättälä, and Lahelma 2002). This is in addition to the powerful influence of other social variables like class and gender that influence health-related behavioral practices like smoking positively or negatively. To minimize or deny the role of social processes in the onset of health problems stemming from such practices renders any other explanation incomplete.

The relegation of social factors to a distant supporting role in studies of health and disease causation reflects the pervasiveness of the biomedical model in conceptualizing sickness. The biomedical model is based on the premise that every disease has a specific pathogenic origin whose treatment can best be accomplished by removing or controlling its cause using medical procedures. Often this means administering a drug to alleviate or cure the symptoms. According to Kevin White (2006), this view has become the taken-for-granted way of thinking about sickness in Western society. The result is that sickness has come to be regarded as a straightforward physical event, usually a consequence of a germ, virus, cancer, or genetic affliction causing the body to malfunction. “So for most of us,” states White (2006: 142), “being sick is [thought to be] a biochemical process that is natural and not anything to do with our social life.” This view perseveres, White notes, despite the fact that it now applies to only a very limited range of medical conditions.

The persistence of the biomedical model is undoubtedly due to its great success in treating infectious diseases. Research in microbiology, biochemistry, and related fields resulted in the discovery and development of a large variety of drugs and drug-based techniques for effectively treating many diseases. This approach became medicine’s primary method for dealing with many of the problems it is called upon to treat, as its thinking became dominated by the use of drugs as “magic bullets” that can be shot into the body to cure or control afflictions (Dubos 1959). As historian Roy Porter (1997: 595) explained: “Basic research, clinical science and technology working with one another have characterized the cutting edge of modern medicine. Progress has been made. For almost all diseases something can be done; some can be prevented or fully cured.” Also improvements in living conditions, especially diet, housing, public sanitation, and personal hygiene, were important in eliminating much of the threat from infectious diseases. Epidemiologist Thomas McKeown (1979) found these measures more effective than medical interventions on mortality from water and food-borne illnesses in the second half of the nineteenth century.

However, as a challenge to the biomedical model, McKeown’s thesis is considered rather tame since a rise in living standards naturally improves health and reduces mortality. Moreover, McKeown has been criticized for his focus on the individual when an analysis of social structural factors would have been more informative (Nettleton 2006). For example, David Blane (1990) subsequently investigated changes in mortality in Britain between 1870 and 1914 in relation to the purchasing power of workers and the quality of their work environment. He found that the increased capability to purchase goods and services, along with better work conditions, had a stronger effect on reducing mortality than improvements in nutrition and sanitation. In this instance, the decisive variable was ultimately structural, namely, the collective actions of workers in obtaining higher wages and an improved work situation.

The general improvement in living standards and work conditions combined with the biomedical approach to make significant inroads in curbing infectious disease. By the late 1960s, with the near eradication of polio and smallpox, infectious diseases had been severely curtailed in most regions of the world. This situation led to longer life spans which were reflected in the change in the pattern of diseases, with chronic illnesses – which by definition are long-term and incurable – replacing infectious diseases as the major threats to health. This epidemiological transition occurred initially in industrialized nations and then spread throughout the world. It is characterized by the movement of chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, and stroke to the forefront of health afflictions as the leading causes of death. As Porter (1997) observed, cancer was familiar to physicians as far back as ancient Greece and Rome, but it has become exceedingly more prevalent as life spans increase.

As for heart disease, Porter notes the comments of a leading British medical doctor who observed in 1892 that cardiac deaths were “relatively rare.” However, within a few decades, heart disease had become the leading cause of death throughout Western society as people lived longer. New diagnostic techniques, drugs, and surgical procedures including heart transplants, by-pass surgery, and angioplasty were developed in response. Porter (1997: 585) also finds that greater public awareness of risk factors like smoking, poor diet, obesity, and lack of exercise along with lifestyle changes made a fundamental contribution to improving cardiovascular health.

The transition to chronic diseases meant medicine was increasingly called upon to confront the health problems of the “whole” person, which extend well beyond singular causes of disease such as a virus that fit the biomedical model. As Porter pointed out, even though the twentieth century witnessed the most intense concentration of attention and resources ever on chronic diseases, they have nevertheless persisted. “It can be argued,” states Porter (1997: 594), “that one reason why there has been relatively little success in eradicating them is because the strategies which earlier worked so well for tackling acute infectious diseases have proved inappropriate for dealing with chronic and degenerative conditions, and it has been hard to discard the successful ‘microbe hunters’ formula.”

Consequently, modern medicine is increasingly required to develop insights into the social behaviors characteristic of the people it treats. According to Porter, it is not only radical thinkers who appeal for a new “wholism” in medical practice that takes social factors into consideration, but many of the most respected figures in medicine were insistent that treating the body as a mechanical model would not produce true health. Porter (1997: 634) states:

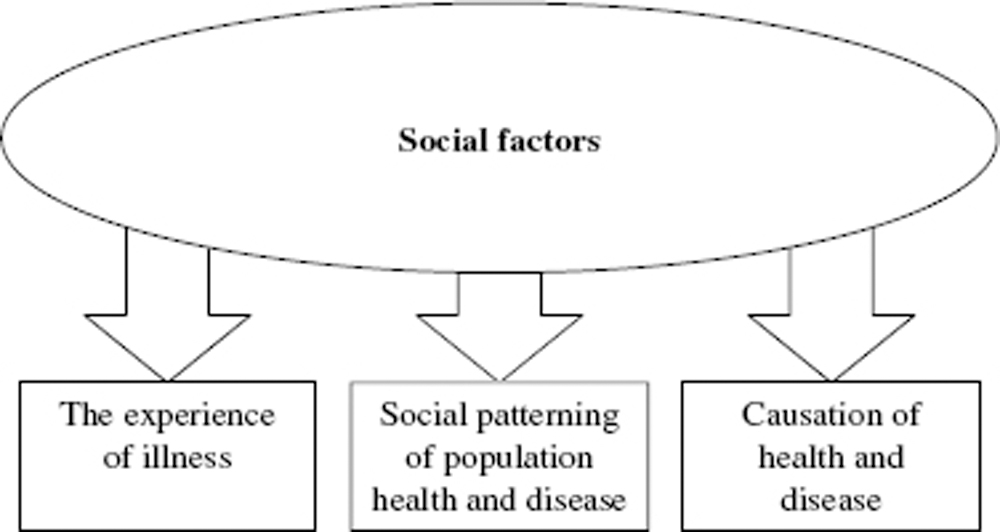

Figure 1.1 The direct effects of social factors on health and disease

Disease became conceptualized after 1900 as a social no less than a biological phenomenon, to be understood statistically, sociologically, and psychologically – even politically. Medicine’s gaze had to incorporate wider questions of income, lifestyle, diet, habit, employment, education, and family structure – in short, the entire psychosocial economy. Only thus could medicine meet the challenge of mass society, supplanting laboratory medicine preoccupied with minute investigation of lesions but indifferent as to how they got there.

Contemporary physicians now treat many health maladies that are aptly described as “problems of living,” dysfunctions that may involve multiple sources of causation, including those that are social in origin and part of everyday life. This includes social structural factors like class, living conditions, and social capital that can cause health or illness. These factors are causal because good or bad health originates from their influence. Consider, for example, the problem of low birth-weights among newborn babies. Such babies are more likely to have health problems than infants with normal birth-weights and less likely to survive the postnatal period. In researching this situation, Dalton Conley, Kate Strully, and Neil Bennett (2003) determined that if there are two groups of couples – one with high incomes and the other with low incomes – and each group has the same 20 percent biological predisposition toward having a low-birth-weight baby – the high-income group has a very high probability of counteracting their biological predisposition with better nutrition and prenatal care. In this instance, social factors – namely, income and how it translates into better education, living situations, jobs, quality medical care, and a good diet and other healthy lifestyle practices – reverse the biological risk. In the low-income group, the biological risk proceeds unimpeded. In both groups, social factors are causal in that biological predispositions are blunted in the high-income group and do not allow the biological risk to be countered in the low-income group. In fact, it could be argued that low income and how it signifies poor education, less healthy living situations, inadequate employment, less quality medical care, and poor diets along with less healthy lifestyle practices like smoking and alcohol abuse, promotes the biological risk into reality.

Social factors not only can determine whether or not a person becomes sick, but also shape the pattern of a population’s health and disease, as well as how people experience illness. The direct effects of social factors on health and disease are depicted in figure 1.1. First, social factors can mold the illness experience, for example, in helping or hindering adaptation, alleviating or exacerbating symptoms by making remedies more or less accessible, providing therapeutic or detrimental environments, or in causing good or poor health care to be available. Second, social factors determine the social patterning of health, disease, and mortality at the population level. All societies have social hierarchies and within those hierarchies health and longevity invariably reflect a gradient in health that is better at the top than at the bottom, while most diseases are also concentrated at earlier ages at the bottom. Third, is the topic of this book: the social causation of health and disease that will be discussed in this and forthcoming chapters.

However, as biostatistician Ronald Thisted (2003) points out, assembling convincing evidence about the social determinants of health is a challenge because of difficulties in linking the social with the biological. Although social factors are associated with various causes of mortality, he states that the mere association of such factors with health or a disease does not necessarily prove causality. Since the concept of a determinant requires a mechanism for action, finding social mechanisms at the aggregate level that affect health and disease at the individual level is a necessary element of proof that social factors are causal. Thisted suggests that a strategy for locating such mechanisms is the use of the traditional epidemiological triad of agent, host, and environment. Agents are the immediate or proximal cause of a particular disease and can be biological, nutritional, chemical, physical, or social. Hosts are the people susceptible to the agent, and the environment consists of factors external to the person, including agents, which either cause or influence a health problem.

The relevance of this strategy is apparent from the different roles social factors perform in the agent–host–environment triad. Agents can be social as seen in the health effects generated by class position, occupations, neighborhoods, and lifestyles; human hosts reflect traits that are both social (habits, customs, norms, and lifestyles) and biological (age, sex, degree of immunity, or other physical attributes that promote resistance or susceptibility); while features of the environment are not only physical but social with respect to poverty and unhealthy living conditions, as well as the social relationships, norms, values, and forms of interaction in a particular social context. Health-related lifestyles are of particular relevance as a social mechanism producing positive or negative health outcomes. As Anthony Giddens (1991: 81) points out, lifestyles can be defined as a more or less integrated set of practices that fulfill utilitarian needs and give material form to particular narratives or expressions of self-identity, such as class position. Everyone has a lifestyle, even the poor. When it comes to health, lifestyles have multiple roles in that they function as a collective or shared pattern of behavior (agent) that is normative in particular settings (environment) for the individual (host). As will be discussed in chapter 3, health lifestyles can be decisive in determining an individual’s health and longevity. Some 40 percent of premature deaths in the US have been linked to unhealthy lifestyle practices such as smoking, alcohol abuse, overeating, and a lack of exercise (Mokdad et al. 2004).

Thisted, however, does not focus on lifestyles, but examines the preconditions for cholera. He notes the link between the biological agent (Vibrio cholerae bacteria) and poor sanitation, observing that poor sanitation is often a consequence of social conditions like poverty and a lack of infrastructure. In this case, the environment could serve as the social mechanism, while social factors might also be important for the host with respect to the availability of modern vaccines. Except for the agent, Thisted concludes that many of the preconditions for cholera may indeed result from social rather than biological factors. He comes to a similar conclusion for the noninfectious problems of hypertension and homicide, suggesting each can be understood through the model of agents and hosts interacting in a suitable environment.

Yet he maintains that the validity of social mechanisms has not been proven beyond a doubt and seriously questions whether the effects of such mechanisms can account for much of the variation in health. He compares differences in the percentages of deaths in the black and white population in the United States in 2000 and, while noting the higher percentages in deaths for blacks, nonetheless finds the differences are not extreme for mortality from diabetes and homicide in particular. While a disadvantaged social situation may cause many blacks to have greater exposure than most whites to these afflictions and bear some responsibility for the differences, Thisted states that most individuals of both races do not die from diabetes and homicide, and therefore social determinants are likely to have a low level of causation.

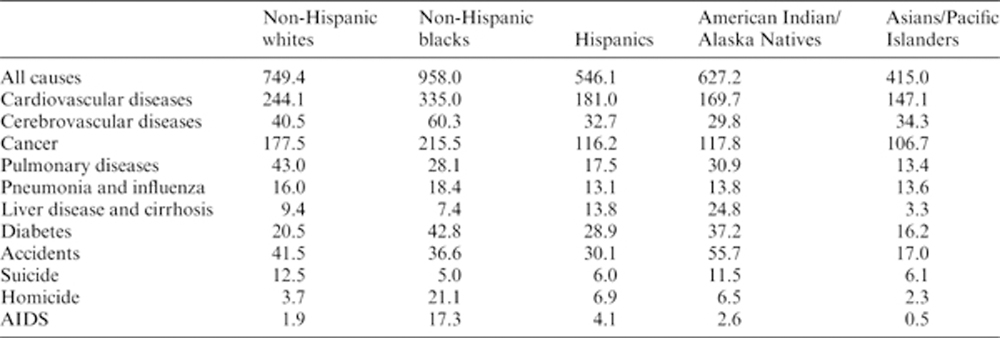

Table 1.1 Age-adjusted death rates for selected causes of death, according to race, United States, 2007 (deaths per 100,000 resident population)

Source: National Center for Health Statistics 2010.

In order to put this critique in perspective, the age-adjusted mortality data for all races in the United States in 2007 (the most recent year available as this book goes to press) are shown in table 1.1. For mortality from all causes, table 1.1 shows that non-Hispanic blacks have the highest death rates of 958 per 100,000 persons, followed by non-Hispanic whites (749.4), American Indians/Alaska Natives (627.2), Hispanics (546.1), and Asians/Pacific Islanders (415.0). Non-Hispanic blacks have the highest rates for each specific cause of death in table 1.1, except for pulmonary disease and suicide that is greater among non-Hispanic whites, and liver disease/cirrhosis and accidents that are higher among American Indians/Native Alaskans. Particularly striking are the exceptionally high death rates for non-Hispanic blacks for heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases (strokes), cancer, diabetes, homicide, and AIDS. While most individuals do not die from diabetes and homicide, they do die from heart disease, cancer, and cerebrovascular diseases and blacks are clearly well ahead of whites in these causes of mortality.

If we compare the 2007 mortality rates for diabetes and homicide shown in table 1.1 to the 2000 results used by Thisted, we see the pattern is virtually the same. In 2000, there were 42.5 deaths per 100,000 persons from diabetes for blacks and 22.8 for whites. In 2007, there were 42.8 deaths for blacks compared to 20.5 for whites – which is almost identical to 2000, except for some slight improvement among whites. Black rates for diabetes are more than twice as high as those for whites for both periods. For homicide, there were 20.5 deaths for blacks in 2000 and 21.1 in 2007, compared to 3.6 and 3.7, respectively, for whites. Overall, black rates for homicide are more than five times higher than white rates. Consequently, the differences are not slight as suggested, but extreme. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke show similar outcomes. These death rates are clearly unequal which points toward some important differences in the lives of non-Hispanic blacks and whites in relation to mortality. These health outcomes cannot all be blamed on biology. In fact, very little of it can be attributed to biological differences between the races (Holtz et al. 2006). What is decisive in many cases are social factors, as seen in the examples of diabetes and HIV/AIDS.

Diabetes is of growing importance in the United States and it is clear that race is a key variable in this development, despite claims that race is simply a social label that by itself should not have any effect on health. What makes race most important with respect to health in American society is its close association with being affluent or poor. Even though members of all races are in each socioeconomic category and many whites are poor, blacks and Hispanics are over-represented among lower-income groups (Hattery and Smith 2011; D. Williams and Sternthal 2010). As for diabetes, both the Type 1 and Type 2 versions are diseases in which excess amounts of sugar (glucose) in the blood damage the body’s organs – promoting kidney failure, heart disease, stroke, blindness, amputations of limbs, and other problems. Type 1 typically appears in childhood when the pancreas quits producing insulin that controls blood sugar levels because the body’s immune system has destroyed the cells that make it. Type 2 or adult onset diabetes is the most common form of the disease and usually develops in people after the age of 40. Some 90 percent of all diabetics are Type 2. This type features the ability to make insulin, but the inability of the cells to use it to control blood sugar levels. Type 2 diabetes is often controlled through diet and exercise, but if this fails then oral medications and/or insulin injections are required.

The New York Times published a series of investigative articles on diabetes in New York City in 2006. The New York Times cited Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) figures indicating that 20.8 million Americans nationwide had diabetes and 41 million more were in a prediabetic stage. One in three children born at the time could expect to become diabetic; for Hispanics, it may be as high as one in every two children – thereby suggesting a future explosion in the numbers of diabetics in the United States. In New York City, the percentage of diabetics has already increased 140 percent in the last decade (Kleinfield 2006a). The number of diabetics in the city is about 800,000 or one in every eight residents. In East Harlem, the epicenter of the city’s diabetes crisis, the ratio is one in every five residents. Diabetes is the only major disease in New York City that is increasing with respect to both the number of new cases and the number of people who die from it. New York Times reporter N. R. Kleinfield (2006a: A1) describes the situation in one hospital in the Bronx when observing that nearly half of the patients there on any given day were admitted for some health problem due to diabetes.

Genetics plays a critical role in that diabetes is more prevalent in certain families and groups than others. A variant gene (TCF7L2) has been discovered that increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes and is carried by more than a third of the American population (Grant et al. 2005). Since people carry two copies of each gene, one inherited from each parent, the extent of the risk depends on whether one or two copies of it have been inherited. The estimated 38 percent of Americans with only one copy are 45 percent more likely than the unaffected population to come down with the disease, while the 7 percent who have inherited two copies are 141 percent more likely than those without the gene to develop diabetes. This gene has existed in the American gene pool for generations and its presence in the body does not guarantee its activation; rather, it enhances the risk. However, the rapid acceleration of new cases in recent years cannot be explained by genetics alone since the human gene pool does not change that fast.

Instead, the culprit appears to be social behavior and is inextricably linked to race and income (Kleinfield 2006b). Low income is significant because of what it signifies with respect to diet (sugar and high fats), exercise (little or none), and medical care (inadequate). Race is important because blacks and Hispanics are twice as likely as whites to become diabetic and more than half of New York City’s population is comprised of people in these two racial categories. Affluent and predominately white neighborhoods like the Upper West Side, Brooklyn Heights, and the Upper East Side have low rates of diabetes. Working-class areas like Ridgewood in Queens have moderate rates, while largely black and Hispanic low-income areas like East Harlem have a virtual diabetes epidemic. Some 16–20 percent of all adults in East Harlem have diabetes (Kleinfield 2006b).

In this situation, the host is genetically-predisposed individuals, the agent is negative health lifestyles, and the environment is socially and economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in New York City. The social mechanism triggering the disease is the agent: negative health lifestyles, notably poor eating practices and an absence of exercise. Many more grocery stores selling healthy foods are available, for example, in the Upper East Side than in East Harlem, although the two areas border each other. Also many of the residents of East Harlem expressed a pervasive fatalism about coping with the disease. They reported being stressed or depressed, or both. They got tired of checking their blood sugar levels and taking medications, and would give in to the desire to smoke, drink heavily, or simply eat sweets or high-fat foods that they needed to avoid, in order to obtain a momentary pleasure. One diabetic woman said she had too much to worry about, such as having a job and paying the rent, so she was not going to also worry about eating a piece of cake. Some had other health problems, including asthma or HIV, that they believed were more serious and required more attention. Since diabetes is a silent and unobtrusive disease unaccompanied by pain as the high blood sugar levels it produces damage the body, dealing with diabetes was often thought of as something that could be put off until another day.

The New York Times team also found that Asians, New York City’s fastest growing racial minority, were especially susceptible to Type 2 diabetes and 60 percent more likely to get the disease than non-Hispanic whites (Santora 2006). Additionally, Asians developed diabetes at far lower body weights than people of other races. For the large influx of Chinese immigrants into the city, the social mechanism for diabetes was also a negative health lifestyle. They often rejected traditional Chinese foods in favor of high-calorie processed foods, large food portions, and a sedentary lifestyle that seemed consistent with American culture. Children in particular were immersed in an environment of fast-food restaurants, television ads for junk food, high-sugar drinks at school and few opportunities for exercise, and snacks loaded with fats and sugar.

The extent of diabetes in New York City is the highest of any metropolitan area in the country (nearly a third higher than in the nation as a whole). The city is in the vanguard of a surge in diabetes that may be extended nationally, as negative health lifestyles increasingly trigger the disease in susceptible people – especially racial minorities. This New York Times investigative reporting not only reveals how powerful social structural factors like class and ethnicity can be in relation to health, but also how the influence of these structural variables is mediated and expressed through culture. For example, the Chinese children opted for the high-sugar and high-fat foods they associated through television advertising with American culture, while devaluing the traditional foods of their homeland. The grocery stores in the affluent Upper East Side stocked fresh produce and healthier foods consistent with the tastes of their customers than the food outlets in East Harlem, whose customers had less money, wanted cheaper foods, and were less discriminating about the food they consumed. Thus class boundaries were also cultural boundaries and in a very real sense constituted health boundaries as well.

HIV/AIDS is another example of how race (and class) serves as a social determinant of health in the United States. In the beginning (the mid-1980s), HIV/AIDS was a disease most characteristic of white homosexual males. But gay men, many of whom are affluent and well-educated, were the first to change their social behavior by adopting safe sex techniques in large numbers and the pattern of the disease changed dramatically. By the 1990s, the magnitude of the epidemic – even though it began to decline after 1995 – had shifted especially to non-Hispanic blacks and also to Hispanics. Mortality rates for HIV/ AIDS for 2007 show that non-Hispanic blacks have the highest rates by far of any race for both males and females. Black males had a mortality rate of 4.5 per 100,000 compared to 6.3 for Hispanics and 2.5 for non-Hispanic whites. For females, the death rate was 11.3 for non-Hispanic blacks, 1.8 for Hispanics, and 0.5 for non-Hispanic whites. Most women – some 85 percent in 2009 – contract HIV through sexual intercourse with infected men.

There are no known biological reasons why racial factors should enhance the risk of HIV/AIDS. Simply being poor and living in economically disadvantaged areas is not the entire answer as many Hispanics and whites are poor, but have lower rates. In addition to poverty, joblessness, minimal access to quality medical care, and a reluctance to seek treatment because of stigma, social segregation is also a factor. Edward Laumann and Yoosik Youm (2001) conclude that blacks have the highest rates of sexually-transmitted diseases because of the “intra-racial network effect.” They point out that blacks are more segregated than other racial groups in American society and the high number of sexual contacts between an infected black core and a periphery of yet uninfected black sexual partners act to contain the infection within the black population. Laumann and Youm determined that even though a peripheral (uninfected) black has only one sexual partner, the probability that partner is from the core (infected) group is five times higher than it is for peripheral whites and four times higher than for peripheral Hispanics. In this instance, the core is the agent, the periphery the host, and the intra-racial network the environment.

The seminal work on the role of social factors in disease causation in medical sociology is that of Bruce Link and Jo Phelan (1995, 2000; Carpiano, Link, and Phelan 2008; Phelan et al. 2004; Phelan, Link, and Tehranifar 2010). Link and Phelan maintain that social conditions are fundamental causes of disease. In order for a social variable to qualify as a fundamental cause of disease and mortality, Link and Phelan (1995: 87) hypothesize that it must (1) influence multiple diseases, (2) affect these diseases through multiple pathways of risk, (3) be reproduced over time, and (4) involve access to resources that can be used to avoid risks or minimize the consequences of disease if it occurs. They define social conditions as factors that involve a person’s relationships with other people. These relationships can range from ones of intimacy to those determined by the socioeconomic structure of society.